12 SERVING IT

The social sacrament

From coffee ceremony to travel mug

Ritual often chooses for its vehicle consciousness-altering substances such as wine, peyote, or coffee. People may assume a bit of God resides in these substances, because through using them they are separated for a moment from the ordinariness of things and can seize their reality more clearly. This is why a ritual is not only a gesture of hospitality and reassurance but a celebration of a break in routine, a moment when the human drive for survival lets up and people can simply be together. This last aspect is to me the fundamental meaning of the coffee break, the coffee klatsch, the happy hour, and the after-dinner coffee. These are secular rituals that, in unobtrusive but essential ways, help maintain humanness in ourselves and with one another.

In many cultures, the ritual aspects of drinking tea or coffee are given semireligous status. The most famous of such rituals is the Japanese tea ceremony, in which powdered green tea is whipped in a traditional bowl to form a rich frothy drink, then is ceremonially passed, in complete silence, from one participant to the next. The tea ceremony is consciously structured as a communal meditation devoted to contemplating the presence of eternity in the moment. Doubtless the caffeine in the tea aids in such psychic enterprise.

Allowed to degenerate, however, such rituals simply become excuses to display our ancient tea bowls, deco martini pitchers, or ingenious new espresso machines. The whiff of the eternal in the present, appreciated alone or shared with others, is what ultimately justifies all this fancy gear.

COFFEE AS SACRAMENT

Coffee has a long history as spiritual substance. Frederick Wellman, in Coffee: Botany, Cultivation, and Utilization, describes an African blood-brother ceremony in which “blood of the two pledging parties is mixed and put between the twin seeds of a coffee fruit and then the whole swallowed.”

Coffee in its modern form, as a hot, black beverage, was first used as a medicine, next as an aid to prayer and meditation by Arabian monastics, much as green tea is used by Zen monks in Japan to celebrate and fortify. Pilgrims to Mecca carried coffee all over the Muslim world. It became secularized, but the religious association remained. Some Christians at first were wont to brand coffee as “that blacke bitter invention of Satan,” as opposed to good Christian wine, but in the sixteenth century Pope Clement VIII is said to have sampled coffee and given it his official blessing.

The Coffee Ceremony

For people in the horn of Africa and parts of the Middle East, coffee has maintained its religious connotations, and the ritual aspects remain conscious and refined. Ethiopians and Eritreans brought their coffee ceremonies with them as they immigrated to the United States. My first experience with a formal coffee ceremony was in the apartment of an Eritrean friend in a thoroughly urban part of Oakland, California. His wife carefully roasted the green coffee beans in a shallow pan, passed the just-roasted, steaming beans around the room so that everyone could enjoy their sweet, black smoke, cooled them on a small straw mat, ground them in an electric grinder (at home in Eritrea she would have used a large mortar and pestle, but she explained that the pounding disturbed her downstairs neighbors!), brewed the coffee in a traditional clay pot, and served it in tiny cups. The entire event was an opportunity to talk and gossip while basking in the smell and spectacle of the preparation of the beverage whose consumption consummated the morning.

Since then I have participated in many similar ceremonies with African friends, in living rooms, in roadside hotels, and, most memorably, in family compounds in the Ethiopian countryside, where coffee is celebrated, not only as catalyst for community, but as the crop on which the villagers’ livelihood depends. Occasionally the ritual was cut short for reason of time and one step or other was omitted, but I always felt that saturating every gesture was an unpretentious but genuine reverence for the gift of coffee, for the pleasure it brings us, and for the encouragement to community its gentle intoxication generates.

If American intellectuals had turned to the horn of Africa or Arabia rather than to Japan for their philosophy of art early in this century, the coffee ceremony might well rival the tea ceremony in influence. Though less formal, it is every bit as moving and elegant.

A World of Coffee Ceremonies

On a less literal level, a multitude of coffee ceremonies take place simultaneously all over the world: in office lunchrooms, in espresso bars, in Swedish parlors, in Japanese coffeehouses, wherever coffee drinkers gather to stare into space, to read a newspaper, or to share a moment, outside time and obligation, with their friends. Ritual is further wrapped up in the smell and taste of coffee. Certain aromas, flavors, gestures, and sounds combine to symbolize coffee and suggest a mood of contemplation or well-being in an entire culture. This, I am convinced, was the reason for the persistence of the pumping percolator in American culture in the 1940s through ’60s. To Americans of that era, the gentle popping sound of the percolator and the smell the popping liberated signified coffee and made them feel good before they even lifted a cup.

Other cultures have similar associations. To people from the Middle East and parts of Eastern Europe, the froth that gathers in the pot when brewing coffee is an indispensable part of the drink, not only because it tastes good but because it symbolizes the meditative glow that comes with brewing and consuming coffee. Italians put a comparable, if somewhat less ceremonial, emphasis on the froth produced by espresso brewing. An Italian will not take a tazzina of espresso seriously if it is not topped with a layer of what to a filter-coffee drinker may look like gold-colored scum. Yet this golden scum, or crema, is what marks espresso as the real thing. Similar satisfaction resides in the milk froth that tops such drinks as caffè latte and cappuccino. The froth has almost no flavor, but a cappuccino is not a cappuccino without it.

Ritual is what gives validity to the extraordinary variety of cups, pots, and paraphernalia that human beings have developed to transport coffee from the pot to the palate. Practical issues are involved, notably keeping the coffee hot on the way, but most design variations are refinements that answer the need for the satisfaction of ritual. Of course, there is nothing to stop people from buying new gadgets or fancy pots as Christmas presents or to make an impression, but purchases made for the wrong reasons usually carry a roundabout retribution. Call it garage-sale karma. If you do not really care about espresso, for example, your new machine may end up in your driveway some Sunday selling for $5.

Coffee Anticeremonies

A comedian recently advanced the idea of drive-through communion as a way of counteracting declining church attendance.

For many of us what has happened to the public ritual of coffee in recent years is almost as grotesque. Rather than a hearty ceramic mug of drip coffee or elegant demitasse of espresso, we buy caffè lattes dispensed into cardboard with all the finesse of pumping gas. Rather than coffee as a catalyst for a brief moment alone with our thoughts, or a chat with a friend, or a round of banter with a waiter or waitress, that cardboard-encased latte is one element in a multitasking drive to work combining lukewarm coffee, a Danish lifted off a napkin on the lap, and a series of cell phone calls to clients.

Nothing to be done about this latest subversion of pleasure, of course, except exhort one another to slow down and sniff the coffee occasionally and perhaps replace the cardboard cup with a stainless steel, insulated mug.

But I often with I could transport some of the local baristas and their overcaffeinated, underserved customers to Italy, where they could experience a coffee ritual as elegant as it is brief and efficient. No one is in as much of a hurry as Italians, yet they always take a couple of minutes to give themselves to coffee and the moment that surrounds it: the tiny cup, always delivered with a small saucer and spoon, always half filled with rich, perfumy espresso, placed with economy of gesture on a clean bar. For a few seconds, nothing intrudes between the tiny pool of fragrant coffee and drinker. Then the cup is returned to the saucer with a definitive clack, the customer is on her or his way, carrying a respite, however momentary, from the press and clutter of obligation.

KEEPING IT HOT

The only absolutely practical contribution that serving paraphernalia can make to coffee-drinking pleasure is keeping the coffee hot. This contribution is an extremely important one, however. It involves a delicate balance between too much heat, which bakes the coffee, and too little, which leaves the coffee lukewarm and our senses ungratified. One way to keep coffee warm is to brew it in, or into, a preheated, insulated carafe. The other way is to apply some heat under the coffee as it is brewed.

An insulated carafe is by far the best approach technically. Any external heat, no matter how gentle, drives off delicate flavor oils, cooking the coffee and hardening its flavor.

Fortunately, there is no lack of brewing devices that protect coffee heat in insulated receptacles during and after brewing. Automatic, filter-drip machines that brew directly into insulated carafes are available in a variety of styles and prices, and several designs of French-press brewer replace the usual glass brewing decanter with an insulted metal or plastic decanter. Designs incorporating insulated carafes typically cost a bit more than those that brew in or into conventional glass decanters, but for anyone who cares about coffee quality it is money well spent.

As for the less desirable expedient of keeping coffee hot by putting some heat under it, solutions range from the familiar hot plates on automatic drip machines to gentler approaches like candle warmers and insulated cloth wraps for French-press pots. Filter-drip purists who pour the water over the coffee by hand have the option of keeping their coffee hot by immersing their brewing decanters in a bath of warm water. Simply gently heat some water in any kitchen pan or pot large enough to accommodate both water and brewing decanter, and leave the combination over a very low flame as you enjoy the coffee. Of all of the heat-applying approaches to keeping coffee hot, this one is probably the least destructive to flavor.

SERVING PARAPHERNALIA

Covered serving pots have been in vogue since the Arabs started drinking coffee. At import stores you can find the traditional Arabian serving pot, with its S-shaped spout, Aladdin’s lamp pedestal, and pointed cover. You can also occasionally find an ibrik, or Middle Eastern coffeemaker, with an embossed cover for keeping coffee hot. The changes in English coffeepot design are fascinating. On one hand stands the severe, straight-sided pewter pot of the seventeenth century, which suggests a Puritan in a stiff collar; on the other, the silver coffeepot of the Romantic period, which takes the original Arabian design and makes it seethe with exotic squiggles and flourishes.

Coffee-server design has continued to swing between these extremes. Although in the past two decades the coffeepot and matching sugar dish and creamer have been out of fashion, they are making a modest comeback, right next to the martini pitcher and cocktail shaker. Always favored by an esoteric few, the continental-style coffee server is an excellent choice for the coffee ritualist. Smaller than the English-style pot, it has a straight handle that protrudes from the body of the pot. The French often serve the coffee portion of the café au lait in this kind of pot and put the hot milk in a small, open-topped pitcher. You pick up the coffee with one hand, the milk with the other, and pour both into the bowl or cup simultaneously, in a single, smooth gesture. The straight handle, which points toward you and allows you to pour by simply twisting your wrist, facilitates this important operation. These pots are available in copper for around $25.

The coffee thermos, the space-age contribution to coffee serving, works like the old thermos jug but has design pretensions and is much easier on flavor than reheating. The cheapest (about $15 to $20) are plastic and embody a bright, postmodern chic. Bauhaus classicists can choose from clean-lined, stainless steel designs (around $25), while crystal-and-silver types can find thermoses ($60 and up) that rework traditional nineteenth-century designs in brass or silver-plate.

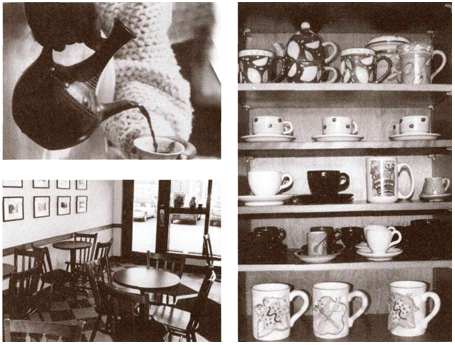

Mugs, Cups, Saucers

Coffee is probably best served in ceramic mugs or cups that have been warmed first with a little hot water. There are many stylistic directions to take: fancy china, deco and moderne revivals, new-wave whimsy, hand-thrown earthenware, inexpensive machine-made mugs that look hand-thrown, classic mugs and cups from restaurant suppliers, and contemporary imported restaurant ware from Europe. I prefer the restaurant-supply cup; it looks solid, feels authentic, reflects the hearty democratic tradition of coffee, and bounces when you drop it.

Straight espresso and after-dinner coffees brewed double strength are traditionally served in a half-size cup, or demitasse. It seems appropriate to drink such intense, aromatic coffee from small cups rather than from ingratiatingly generous mugs. You should have the small demitasse spoons that go with the cups; an ordinary spoon looks like a shovel next to a demitasse. You can save considerable money on such gear at restaurant-supply stores.

The half-size cups used in the Middle Eastern and North African cuisine traditionally do without the little ceramic handle and sometimes are mounted on elegant metal stands. Most large North American cities today harbor neighborhoods of Middle Eastern or Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants where specialty stores carry a broad range of goods from back home, including an assortment of traditional cups and coffee gear.

Nearly every traditional espresso specialty has its specialized style of cup, mug, or glass: unadorned espresso or espresso macchiato, a heavy demitasse cup and saucer; cappuccino, a heavy 6-ounce cup and saucer; mocha, a substantial mug; caffè latte, a 12- or 16-ounce glass or bowl; latte macchiato, an 8- or 10-ounce glass.

German and Scandinavian tradition calls for paper-thin porcelain cups for the water-thin coffee served at the traditional Kaffeeklatsch. Andres Uribe, in his book Brown Gold, claims that women at the original German Kaffeeklatsch called their coffee Blumenkaffe, “flower-coffee,” after the little painted flowers that the thin, tealike beverage permitted them to see at the bottom of their Dresden cups.

MILK AND SWEETENERS

When I was a teenager in the Midwest, drinking coffee any other way than black was suspect. People would leer patronizingly at you and tell you that you could not possibly like coffee if you had to add cream and sugar to it. I assume that they did not like beef, because most of them ate it seasoned. Perhaps the midcentury preference for thin, black coffee went along with an equivalent love of characterless white wines, dry martinis, and lager beer. It was as though to admit to liking sweet, heavy drinks was tantamount to confessing some unpardonable moral weakness.

Milk and Coffee

Today, of course, people have no problem whatsoever dousing espresso with kindergarten quantities of milk, not to mention an ounce or two of flavored syrup. The change may be partly owing to the contemporary tendency to brew stronger coffee, which stands up better to milk and sweetener than did the thin, underflavored beverage drunk in America in the years before the advent of specialty coffee. All of the great rich, full-bodied coffees of the world, brewed correctly, carry their flavor through nearly any reasonable amount of milk. And a great, rich, full-bodied coffee brought to a moderately dark roast (not a thin, burned French roast) will carry through milk even better.

Too much milk, of course, cools the coffee, unless you heat it or, better yet, heat it and froth it with the steam wand of an espresso machine. As everyone knows, milk heated conventionally tends to congeal unpleasantly, an aesthetic turn-off avoided by heating and frothing milk with steam. Anyone who enjoys milk in coffee might consider purchasing an inexpensive countertop espresso machine (Category 2) simply to froth and heat milk.

Demon Sugar, Other Sweeteners, and Coffee

The debate over sugar in coffee has raged almost as long as the caffeine controversy, though with considerably less rancor. The inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula, the first recorded coffee drinkers, apparently drank their coffee black and unsweetened, adding only spices. The Egyptians are given credit for having first added sugar to coffee, around 1625, and for having devised the traditional Middle Eastern mode of coffee brewing, in which powdered coffee is brought to a boil together with sugar to produce a sweet, syrupy beverage. The dairy-shy Egyptians still did not think to add milk to their sweetened coffee, however. Although the Dutch ambassador to China first experimented with milk in his coffee in 1660, this innovation did not become widely accepted until Franz George Kolschitzky opened the first Viennese café in 1684 and lured his new customers away from their beer and wine by adding both milk and honey to strained coffee.

Now that granulated sugar is a dietary villain in many circles, people who like to sweeten coffee resort to a variety of alternatives. Artificial sweeteners using saccharine like Sweet’n Low are unsatisfactory; coffee exaggerates their flat, metallic flavor. Aspartame-based sweeteners like Equal resonate with coffee much better, although the aftertaste still may be a touch tinny. To my palate, honey fades away in coffee, but the molasses in dark brown and raw or demerara sugars actually reinforces the rich, dark tones of coffee flavor. You are still consuming sugar, but you are adding some iron and B vitamins. The Japanese recognize the flavor symbiosis of raw sugar and coffee by calling the former coffee-sugar.