13 GROWING IT

How coffee is grown processed, and graded

Growing your own

To imagine an arabica coffee tree, think of a camellia bush with flowers that resemble jasmine. The leaves are broad, shiny, and shaped like an arrow or spearhead. They are three to six inches long and line up in pairs on either side of a central stem. The flowers—small, white, star-shaped blossoms borne in clusters at the base of the leaves—produce an exquisite, slightly pungent scent. The white color and nocturnal aroma of the flowers may suggest that the coffee plant is pollinated by moths or other night-flying insects, but in fact the plant largely pollinates itself. In freshly roasted coffee, a hint of the flowers’ fragrance seems to shimmer delicately within the darker perfumes of the brew, and some coffees, Ethiopia Yirgacheffe for example, are spectacularly floral.

The arabica plant is an evergreen. In the wild it grows to a height of 14 to 20 feet, but when cultivated it is usually kept pruned to about 6 to 8 feet to facilitate picking the beans and to encourage heavy bearing. It is self-pollinating, which accounts for the stability and persistence of famous varieties of the arabica species like typica and bourbon.

Flowering and Fruiting

In such regions as Brazil, where one or two rainy seasons each year are followed by dry seasons, the hills of the plantations whiten with blossoms all at once. In areas with sporadic rainfall the year around, like Sumatra, blossoms, unripe fruit, and ripe fruit may cohabit the trees simultaneously. Most coffee-growing regions fall somewhere between these two extremes, with a broad season of flowering provoked by rain and a longish, relatively dry season of fruiting and harvest.

The scent of an entire coffee plantation in bloom can be so intense that sailors have reported smelling the perfume two or three miles out to sea. Such glory is short-lived, however; three or four days later, the petals are strewn on the ground and the small coffee berries, or cherries as they are called in the trade, begin to form clusters at the base of the leaves.

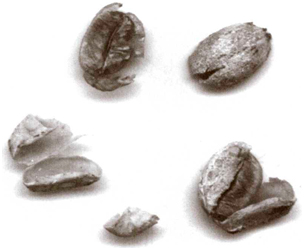

In six or seven months, the coffee cherries have matured; they are oval, about the size of your little finger. Most varieties turn bright red when ripe; a few varieties ripen to a golden yellow. Inside the skin and pulp are nestled two coffee beans with their flat sides together. Occasionally, there are three seeds in one cherry, but a more common aberration is cherries that contain just one seed, which grows small and round, and is sold in the trade as peaberry coffee. Each tree can produce between one and twelve pounds of coffee per year, depending on soil, climate, and other factors. The plants are propagated either from seed or from cuttings. If propagated from seed, a tree takes about three years to bear and six to mature.

Shade vs. Sun

Coffee arabica grows wild in the mountain rain forests of Ethiopia, where it inhabits the middle tier of the forest, halfway between the brushy ground cover and the taller trees. It grows best wherever similar conditions prevail: no frost, but no hot extremes; fertile, well-watered but well-drained soil (soil of volcanic origin seems best). Heavy rainfall can cause the trees to produce too much too fast and exhaust themselves; inadequate rain prevents the trees from flowering or bearing fruit. The tree requires some but not too much direct sunlight; two hours a day seems ideal. The lacy leaves of the upper levels of the rain forest originally shaded the coffee tree.

Coffee planted in managed shade. The coffee trees under the much taller shade trees are about three years old. Antigua Valley, Guatemala.

In many parts of the world, including Central America, Mexico, Colombia, Ethiopia, and other regions, arabica coffee is traditionally grown in shade, which can range from dense thickets of native plants to careful, uniform plantings of imported shade trees. In other parts of the world—Hawaii, the Mandheling region of Sumatra, the Blue Mountain region of Jamaica, and many other places—coffee is not grown in shade because the weather is too rainy and wet and the trees need all the sun they can get. In other places—Yemen, Brazil—coffee is traditionally grown in sun.

The tendency of growers in regions where shade growing is traditional to replace shade-grown coffee groves with new hybrid trees that grow well in sun and bear quickly and heavily is controversial, since these new fields of sun-grown coffee reduce diversity and require more artificial chemical inputs than shade-grown trees.

The Higher the Better (Usually)

Whereas arabica trees planted at low altitudes in the tropics overbear, weaken, and fall prey to disease, trees grown at high altitudes, 3,000 to 6,000 feet, usually produce coffee with a “hard bean.” The colder climate encourages a slower-maturing fruit, which in turn produces a smaller, denser, less porous bean with less moisture and more flavor.

Beware, however, of easy distinctions. Some of the world’s most celebrated coffees are softer bean, including Hawaii Kona, Sumatra Lintong, and Jamaica Blue Mountain.

Traditional vs. Hybrid Varieties

Researchers working in growing countries continue to develop new varieties of arabica that begin to bear fruit more quickly after planting than traditional varieties of arabica, bear more fruit, and are more disease-resistant. Often these hybrid varieties have in their heritage a bit of robusta, the coffee species that is much hardier than arabica but which is (at best) neutral in the cup.

Hybrids and Taste. These hybrid varieties, whether or not they incorporate robusta, often do perform as intended, but many importers and roasters feel that this performance is at the cost of cup quality. For example, they attribute the fall-off in quality of Colombian coffees in recent years to the efforts of the Colombian government to replace “old arabicas,” mostly of the respected bourbon and typica varieties, with the newer, faster- and heavier-bearing Colombia or Colombian variety.

As with generalizations connecting high, growing altitude and superior cup quality, the contention that traditional varieties of arabica are better tasting than newer hybrid varieties can be overstated. Traditional varieties usually display more character in the cup than hybrid varieties, but not invariably.

Genetically Engineered Coffees. Bear in mind that the “new” arabicas are not genetically engineered. They have been developed using traditional methods of cross-pollination and selection. However, two genetically engineered varieties have been developed by technicians in Hawaii.

At this writing they have not yet been released. They may never be, given current public resistance to genetically engineered crops. One variety is designed to simplify machine picking by producing fruit that ripens all at once rather than sporadically. The other variety is a favorite story of the media: It is a variety that grows naturally without caffeine. The chromosomes that cause the plant to produce caffeine apparently have been inverted, neutralizing them. At this writing the first crop from both sets of test trees is on its way, at which point we will have some idea of how these engineered coffees actually taste.

Estates, Plots, and Plantations

The best coffees of the world are grown either on medium-size farms, often called estates, or on peasant plots. Processing of estate coffees is usually done on the farm itself or by consignment at nearby mills. The best peasant-grown coffees are generally processed through well-run cooperative mills. The farmer grows food crops for subsistence and some coffee for exchange. The cooperatives, often government sponsored, attempt to maintain and improve growing practices and grading standards.

In parts of the world with advanced economies and high labor costs, farms may be very large so as to facilitate economies of scale and the efficient use of technology. Mainly in Brazil, but also in Australia and parts of Hawaii, coffee trees may stretch for miles in groves as perfectly tended and monotonous as Iowa corn fields. Coffees from these large farms can range from mass-produced and mediocre (many Brazil coffees) to splendid products of exquisite technical sophistication (the best Brazil coffees).

The poorest-quality coffees of the world are peasant-grown coffees that are not properly picked or handled. In these cases the governments involved usually have failed to provide leadership in encouraging quality and establishing the kind of well-run processing facilities that make the small-holder coffees of Kenya and the Yirgacheffe region of Ethiopia, for example, among the finest origins in the world.

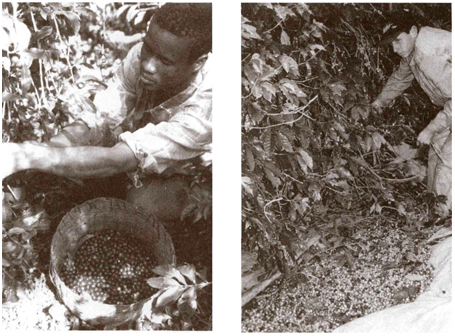

Left, selective coffee picking in East Africa. Right, strip picking in Brazil. In strip picking, the middle part of the branches are stripped of (mostly ripe) coffee fruit, which falls onto sheets laid on the ground beneath the trees. Done properly, as it is being done here, strip picking can be remarkably effective at harvesting only ripe fruit.

Ripe Is Best

Harvesting is one of the most important influences on coffee quality. Coffee processed from ripe cherries is naturally sweet and shimmering with floral and fruit notes. Coffee processed from unripe cherries may taste grassy, green, thin, or astringent. Coffee processed from overripe, shriveled cherries (sometimes called raisins) runs the risk of tasting fermented, musty, or moldy.

Harvesting coffee is particularly challenging because coffee fruit typically does not ripen uniformly. The same branch may simultaneously display ripe red cherries, unripe green cherries, and dry, past-ripe black cherries.

Mechanical coffee harvester at work on a large farm in Hawaii. Fiberglass rods vibrate the branches, shaking ripe fruit loose but leaving most unripe fruit still attached to the branches. These machines are used only on flat terrain in regions with relatively high labor costs: large farms in Hawaii (not Kona), in the Cerrado and Bahia regions of Brazil, and in Australia.

In regions where labor is inexpensive or where families pick their own small plots, trees may be picked repeatedly, and only ripe fruit harvested during each pass through the trees. In part of the world where labor is scarce or expensive, coffee may be stripped from the trees in a single picking. Ripe, unripe, and overripe cherries are all gathered together, along with some leaves and twigs. Although sophisticated sorting methods can compensate to some degree for mass picking, no expedient is quite as effective as repeated, skillful hand picking.

Machines have been developed that selectively pick ripe cherries by vibrating the tree just vigorously enough to knock loose the ripe fruit, while leaving the unripe fruit still attached to the tree. Such machines do not approach the selectivity of a good hand picker, and are used only in regions of the world—Brazil, Australia, and parts of Hawaii—where labor is too costly to support hand picking. Almost all fine coffee is still picked selectively by hand.

Fruit Removal and Drying

How the fruit is removed from the coffee and how it is dried are extraordinarily important to how it finally tastes. If the fruit removal and drying, collectively called processing, is done carefully, the coffee will taste clean and free of distracting off-tastes. Furthermore, the various processing methods—dry, wet, and semidry—influence the cup character of coffee in fascinating and complex ways.

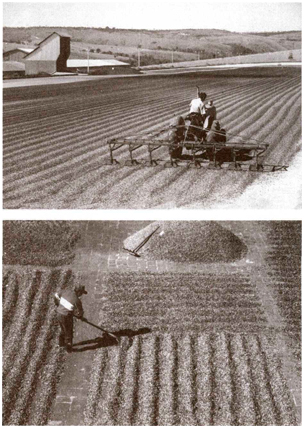

The Dry Method. In this, the oldest of processing methods, the coffee fruit is simply picked and put out into the sun to dry, fruit and all. It is spread in a thin layer and raked regularly to maintain even temperatures from top to bottom of the layer. Drying takes anywhere from ten days to three weeks, and, on larger farms, occasionally may be accelerated by putting the coffee into mechanical driers. The hard, shriveled fruit husk is later stripped off the beans by machine. In the marketplace, coffee processed by the dry method is called dry-processed, unwashed, or natural coffee.

The Wet Method. Here the fruit covering the seeds/beans is removed before they are dried. The wet method further subdivides into the classic ferment-and-wash method and a newer procedure variously called aquapulping or mechanical demucilaging. Regardless of which of the procedures is used, coffee processed by the wet method is called wet-processed or washed coffee.

In the classic ferment-and-wash version of the wet method, the fruit that covers the beans is taken off gingerly, layer by layer. First, the outer skin is gently slipped off the beans by machine, a step called pulping. This leaves the beans covered with a sticky fruit residue. The slimy beans then are allowed to sit in tanks while natural enzymes and bacteria loosen the sticky residue by literally beginning to digest it. This step is called fermentation. If water is added to the fermentation tanks, it is called wet fermentation; if no water is added and the beans simply sit in their own juice, it is called dry fermentation. The fermentation step is one of the main ways coffee-mill operators can nuance the taste of the coffees they process. Dry-fermented coffees usually are more complex and sweet than wet-fermented coffees, which tend to be brighter and drier in taste.

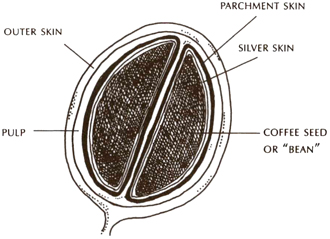

Cross-section of a coffee fruit. In the wet-processing method of fruit removal, the outer skin and pulp are removed immediately after harvesting. The parchment skin and silver skin are removed later, after drying. In the dry-processing method, the entire fruit is dried after harvesting and the various shriveled layers of fruit removed from the bean in a single operation after drying.

After the fermentation step, the coffee is gently washed and then dried, either by the sun on open terraces, where the thin layer of beans is periodically raked by workers, or in large mechanical driers, or in a combination of the two. This leaves a last thin skin covering the bean, called the parchment skin or pergamino. If all has gone well, the parchment is thoroughly dry and crumbly and easily removed. Coffee occasionally is sold and shipped in parchment or en pergamino, but most often a machine called a huller is used to crunch off the parchment skin before the beans are shipped. A last, optional step is polishing, which gives the dry beans a clean, glossy look important to some specialty roasters. Other roasters condemn polishing as pointless and detrimental to taste owing to the friction-generated heat it applies to the beans.

Machine-Assisted Wet-Processing. The mechanical demucilage or aquapulp variation of the wet method is essentially a short-cut approach that removes the sticky fruit residue from the beans by machine scrubbing rather than by fermenting and washing. This mechanized short cut is increasingly popular for two reasons, one admirable and one not so admirable.

The admirable reason: Mechanical demucilaging cuts down on water use and pollution. Ferment and wash water stinks, and communities downstream from coffee mills understandably object to having stinky water injected into their fisheries and water supply.

The not so admirable reason: Removing mucilage by machine is easier and more predictable than removing it by fermenting and washing. Unfortunately, machine demucilaging has been accused of limiting the taste palate of coffee by prematurely separating fruit and bean. By eliminating the fermentation step, the practice definitely robs mill operators of the most important expressive option they have at their disposal to influence coffee flavor. Furthermore, the ecological criticism of the ferment-and-wash method increasingly has become moot, since a combination of low-water equipment plus settling tanks allows conscientious mill operators to carry out fermentation without polluting.

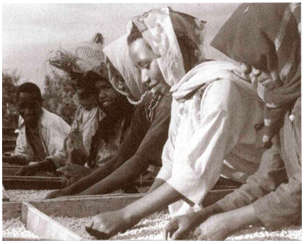

Picking defective beans from coffee drying on raised racks in the Yirgacheffe region of Ethiopia. In most parts of East Africa coffee is dried on raised platforms, which allow air to circulate under and through the drying coffee.

The Semidry or Pulped Natural Method. This procedure is practiced regularly in only two regions of the world, Brazil and certain parts of Sumatra and Sulawesi. The outer skin is removed as it is in the wet process, but the troublesome sticky fruit residue is allowed to dry on the bean and later removed by machine along with the parchment skin.

Keeping the Methods Straight. To summarize, the main technical difference among the various processing methods is how and when the outer skin and the sticky mucilage are removed from the beans. In the dry method, both skin and mucilage remain on the beans throughout the drying process to be removed later by machine. In the semidry or pulped natural method, the outer skin is removed immediately after picking but the sticky mucilage is allowed to dry on the beans and removed later. In the washed method, both outer skin and mucilage are removed immediately, either by controlled fermentation and washing or by machine scrubbing.

Careless Processing and Taste Taints

Regardless of method, there are many moments of truth in processing coffee, and many points when expedience may tempt the mill operator to cut corners.

There are two main categories of flavor taints caused by careless fruit removal and drying. The first is inadvertent fermentation of the sugars in the fruit (not to be confused with the deliberate, controlled fermentation that is part of the ferment-and-wash method). When sugars in the fruit ferment, they impart a taste to the coffee ranging from disturbingly overripe to outright, compost-pile rotten.

The second threat poor processing poses to coffee flavor is a harsh, flavor-dampening taste caused by molds or microorganisms that invade the fruit and/or the bean during drying and storage. These organisms attack the coffee during interruptions in the drying process (the drying coffee may be rained on, for example) or during storage and transportation (the coffee may be too moist when put into shipboard containers, where it develops molds). These tastes are often divided by coffee cup testers into categories—moldy, musty, baggy, medicinal, etc.—but all of these taints share a common sensation, a sort of taste-deadening hardness or harshness.

Flavor and Processing Method

However, if all goes well, each processing method accentuates certain aspects of coffee flavor. Generally, coffees processed by the mechanical mucilage wet method will be brightest, driest, and cleanest tasting. Those processed by the ferment-and-wash wet method will be next brightest and driest, though often a bit fruitier and more complex. Coffees processed by the semidry and the dry methods tend to be fruitiest, most complex, and heaviest in body owing to longer contact with fruit residue during drying.

Most fine coffees are processed by the classic ferment-and-wash wet method. A few, like Jamaica Blue Mountain and some Cost Rica coffees, are not processed by the mechanical mucilage method. A handful of coffees from Brazil and from Sumatra and Sulawesi are processed by the semidry or pulped natural method. Only three of the world’s premium coffees are processed by the dry method: the finest coffees of Brazil and the splendid coffees of Yemen and the Harrar region of Ethiopia.

Why is the wet method used to process most of the finest coffees: Mainly because so much more can go wrong during dry-processing than during wet-processing. Since drying the entire coffee fruit takes so much longer than drying washed beans, there are more opportunities for the fruit to attract mold, ferment, or even rot. Most dry-processed coffee is also picked carelessly, which means there will always be some contamination of flavor by green or overripe fruit. Processed with care, however, dry-processed coffees can be as good as washed coffees, if not better, owing to their complexity and fruit-toned sweetness.

Cleaning and Sorting

The final steps in coffee processing involve removing the last layers of dry skin and remaining fruit residue from the now dry coffee, and cleaning and sorting it. These steps are often called dry milling to distinguish them from the steps that take place before drying, which collectively are called wet milling.

Removal of Dried Fruit Residue. The first step in dry milling is removing what is left of the fruit from the bean, whether simply the crumbly parchment skin in the case of wet-processed coffee, the parchment skin and dried mucilage in the case of semidry-processed coffee, or the entire dry, leathery fruit covering in the case of dry-processed coffee. The machines that do this range from simple millstones in Yemen to sophisticated machines that gently whack at the coffee.

Drying coffee on patios. Top, concrete patio in the Cerrado region of Brazil. Bottom, brick patio in the Antigua Valley of Guatemala. As coffee dries on patios it must be almost constantly raked to prevent the moist beans from clumping and attracting molds or other flavor-inhibiting microorganisms.

Sorting by Size and Density. Most fine coffee goes through a battery of machines that sort the coffee by density of bean and by bean size, all the while removing sticks, rocks, nails, and miscellaneous debris that may have become mixed with the coffee during drying. First machines blow the beans into the air; those that fall into bins closest to the air source are heaviest and biggest; the lightest (and likely defective) beans plus chaff are blown in the farthest bin. Other machines shake the beans through a series of sieves, sorting them by size. Finally, an ingenious machine called a gravity separator shakes the sized beans on a tilted table, so that the heaviest, densest, and best vibrate to one side of the pulsating table, and the lightest to the other.

Coffee showing the dried parchment skin torn and partially removed, revealing the coffee beans inside. Coffee processed by the wet method is dried and conditioned inside this parchment skin “en pergamino.” The parchment skin later is removed in a step called dry milling.

Sorting by Color. The final step in the cleaning and sorting procedure is called color sorting, or separating defective beans from sound beans on the basis of color rather than density or size. Color sorting is the trickiest and perhaps most important of all the steps in sorting and cleaning.

Color Sorting by Eye and Hand. With most high-quality coffees, color sorting is done in the simplest possibly way—by hand. Teams of workers, often the wives of the men who work the fields, deftly pick discolored and other defective beans from the sound beans. The very best coffees may be hand cleaned twice (double picked) or even three times (triple picked). Coffee that has been cleaned by hand is usually called European preparation. Most specialty coffees, since they are whole bean and consumers see what they get, are European preparation.

Color Sorting by Machine. Sophisticated machines can now mimic the human eye and hand. Streams of beans fall rapidly, one at a time, past sensors that are set according to parameters that identify defective beans by value (dark to light) or by color. A tiny, decisive puff of compressed air pops each defective bean out of the stream of sound beans the instant the machine detects an anomaly.

These delicate machines are not widely used in the coffee industry for two reasons. First, the capital investment to install them and the technical support to maintain them is daunting. Second, and perhaps most important, sorting coffee by hand supplies much-needed work for the small rural communities that cluster around coffee mills. The vision of huge rooms filled with women and a scattering of teenage boys patiently picking through piles of green coffee may offend urbanites, but the economic suffering caused by replacing these women with machines and a highly paid technician from the city is not a comfortable alternative either, particularly in small rural communities with strong communal values.

On the other hand, computerized color sorters are essential to coffee industries in regions with relatively high standards of living and high wage demands, places like Brazil and Hawaii. Readers who have seen television depictions of the slums of Rio may doubt that a labor shortage exists in rural Brazil, but it does. The main areas of coffee production in Brazil are quite prosperous, with a per capita income approximately equal to that of Belgium.

At the other extreme of the coffee economic spectrum is Yemen, where even the usual battery of machines that sort coffee by density and size are unknown, and hand sorting and cleaning is the only sorting and cleaning this wonderfully idiosyncratic coffee receives.

Grading and Beyond

The last step in coffee’s complex, labor-intensive trip to market is grading, the procedure whereby agricultural products are categorized to facilitate communication between buyer and seller. Approaches differ from country to country, but there are four main grading criteria: how big the bean is, where and at what altitude it was grown, how it was prepared and picked, and how good it tastes, or its cup quality. Coffees also may be graded by the number of imperfections (defective and broken beans, pebbles, sticks, etc.) per sample.

As the finest coffees move from the status of commodities sold by description to specialty products sold by specific lot, grading becomes less important, and origin (farm or estate, region, cooperative) more important. Growers of premium estate or cooperative coffees may impose a quality control that goes well beyond conventionally defined grading criteria because they want their coffee to command the higher price that goes with recognition and consistent quality.

Even with fine coffee, however, government agencies in growing countries may impose grading standards to encourage and support quality and to attract and reassure foreign buyers. Coffee-growing countries like Kenya, for example, simultaneously promote high standards through imposing strict grading criteria while supporting growers by providing agricultural and social assistance. In many cases, governments may extend their support efforts to the consuming countries, where they promote their growers’ coffees either behind the scenes or directly through media campaigns, like the famous and successful Colombian effort featuring Juan Valdez and his donkey.

Coffees may be subject to still another grading or sorting after they reach the United States. The San Francisco broker Mark Mountanos runs several already premium coffees through additional sophisticated machine sortings to further eliminate defects and sells these ultraselected beans for a premium as “San Francisco Preparation” coffees. Coffee-handling facilities and warehouses elsewhere may provide similar services. As sorting devices increase in sophistication and decrease in price, the industry may see more such regrading of coffees by importers in consuming countries.

Organically Grown Coffees

The issues surrounding coffee and chemical-free or organic agriculture are detailed in Chapter 6. A good deal of the coffee appearing in specialty stores is probably close to chemical-free, simply because the small peasant farmers who grow it cannot afford to purchase chemicals. They raise vegetables, keep some chickens and goats, and grow coffee to supply (a little) cash. The certified Latin America, Timor, and Papua New Guinea organic coffees now appearing in specialty coffee stores may have been grown in chemical-free conditions for years; the certification process simply confirms their chemical-free status for the consumer, while helping the growers understand, systematize, and improve their traditional agricultural processes. The certification movement has thus far reached only Latin America, Timor, and parts of Indonesia and Papua New Guinea. I am certain, however, that virtually all coffees raised in Ethiopia, Yemen, and the Mandheling region of Sumatra are also grown by traditional means, without chemicals.

People, Environment, and Coffee Growing

I outline the social, economic, and environmental issues surrounding coffee growing in Chapter 6 and show how those issues are reflected in the marketing of organic, bird-friendly, fair-trade, and other niche coffees in North American retail stores and web sites. In the larger picture, anyone who buys a specialty coffee by country of origin rather than by supermarket brand name is helping create better economic, social, and environmental conditions in growing countries, since the selling of coffee as an anonymous, price-driven commodity is at the heart of the oppression of the many millions of people in growing countries whose toil and passion go into the long, arduous process of bringing coffee from seedling to market.

Growing Your Own

Some enthusiastic readers may want to begin growing their own coffee. Unfortunately, for most of us this is a dream that is difficult to realize. A true devotee would need a commercial-size greenhouse or a large backyard in or near the tropics. The environment must be frost-free, which eliminates most yards in the United States. Then assume that one mature tree trimmed to about six feet tall will produce an average of two to four pounds of coffee a year. Obviously, a very substantial coffee orchard, a dozen trees at least, would be needed to keep the average coffee lover happy.

Growing It Indoors. If you want just a small specimen, the Coffea arabica is easy to grow indoors, makes a very attractive house plant, and may bear flowers and fruit. You can start a coffee plant in one of three ways. The easiest is to buy a seedling. Although Coffea arabica is not an extremely popular house plant, indoor nurseries occasionally carry it, and most will accept special orders. The next-easiest method is to take a cutting from a friend’s plant and root it. Finally, you can plant some green coffee beans and wait for them to sprout in about three or four weeks. Obviously, the green beans that reach the coffee store are at least a couple of months old, and most will never germinate at all, but if you plant enough beans you should eventually be rewarded with a sprout.

Beans should be planted a little over a half inch deep in good, well-drained potting soil, and kept moist at all times, but not wet. Once the plant has sprouted, treat it as you would a camellia. Keep the soil moist but never wet, and provide plenty of bright indirect or diffused sunlight. Fertilize every other month. If something goes wrong, look up camellia in a good indoor gardening manual for the appropriate advice.

In order to coax your mature coffee plant to flower and bear fruit, you may need to mimic nature by providing a few weeks of “dry” weather (underwater the plant just to the point of allowing its leaves to droop) then giving it plenty of water for a few more weeks. Particularly if you make the heavy-watering part of the cycle correspond to the longer days of spring, you should provoke a flowering and, since Coffea arabica self-pollinates, a tiny but gratifying crop of coffee fruit a couple of months later.

Outdoor Growing. If you live in a frost-free area, you may want to plant some arabica in your yard. Temperatures should not be lower than 60°F normally or lower than 50° for short periods only. Parts of Hawaii are unsurpassed for coffee. It has long been held that coffee could be grown commercially along the southern California coast, but this has never been tried because of high labor costs. Remember, however, that you need to duplicate the conditions of the Ethiopian rain forest: moist, fertile, well-drained soil and partial shade. This last condition is especially important during the long summers in southern California. For more advice on growing, pruning (very important if you wish your tree to produce more coffee), and caring for coffee trees, try to find a copy of A. E. Haarer’s Coffee Growing in the Oxford Tropical Handbooks series, published by Oxford University Press.