14 CELEBRATING IT

Public ceremonies and ritual conviviality

Coffee places

Every social lubricant has its home away from home, its church, as it were, where its effects are celebrated in public ceremonies and ritual conviviality. The café, caffè, or coffeehouse is as old as the beverage itself. The first people to enjoy coffee as a beverage rather than to use it as a medicine or an aid to meditation did so in coffeehouses in Mecca in the late-fifteenth century. The nature of the coffeehouse was established early in history and has changed remarkably little in five hundred years.

A UNIQUE IDENTITY

Jean de Thévenot describes a Turkish coffeehouse of 1664 in Relation d’un voyage fait au Levant:

There are public coffeehouses where the drink is prepared in very big pots for the numerous guests. At these places guests mingle without distinction of rank or creed; nor does anyone think it amiss to enter such places, where people go to pass their leisure time. In front of the coffeehouses are benches with small mats, where those sit who would rather remain in the fresh air and amuse themselves by watching the passersby. Sometimes the coffeehouse keeper engages flute players and violin players, and also singers, to entertain his guests.

The “very big pots” of de Thévenot’s café became the espresso machines or coffee urns of today; the “benches with small mats,” outdoor terraces. And although the café shares many qualities with the bar, saloon, and boîte beloved of drinkers of wine and spirits, it has maintained a subtly unique identity.

Coffeehouse Culture and Caffeine

The customs of coffeehouse and café appear to be intimately connected to the effect of coffee and caffeine on mind and body. Coffee stimulates conscious mental associations, whereas alcohol, for instance, provokes instinctual responses. In other words, alcohol typically makes us want to eat, fight, make love, dance, and sleep, whereas coffee encourages us to think, talk, read, write, or work. Wine is consumed to relax, and coffee to drive home. For the Muslims, the world’s first coffee drinkers, coffee was the “wine of Apollo,” the beverage of thought, dream, and dialectic, “the milk of thinkers and chess players.” For the faithful Muslim it was the answer to the Christian and pagan wine of Dionysus and ecstasy.

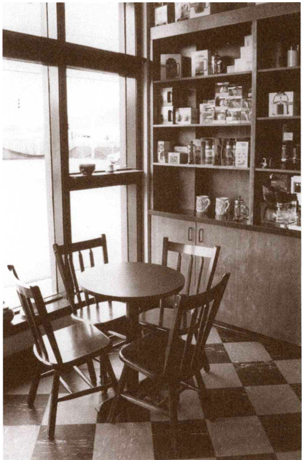

From the inception of the coffeehouse in Mecca to the present, customers in cafés tend to talk and read rather than dance, play chess rather than gamble, and listen contemplatively to music rather than sing. The café usually opens to the street and sun, unlike bars or saloons, whose dark interiors protect the drinker from the encroachment of the sober, workaday world. The coffee drinker wants not a subterranean refuge but a comfortable corner in which to read a newspaper and observe the world as it slips by, just beyond the edge of the table.

The café is connected with work (the truck stop, the coffee break) and with a special brand of informal study. A customer buried in reading matter is a common sight in even the most lowbrow café. The Turks called their cafés “schools of the wise.” In seventeenth-century England, coffeehouses were often called “penny universities.” For the price of entry—one penny; coffee cost two, which included newspapers. One could participate in a floating seminar that might include such notables as Joseph Addison and Sir Richard Steele.

As a matter of fact, aside from the Romanticists, who temporarily switched to plein-air, it is hard to find too many European or American intellectuals of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries who did not spend the better part of their days in cafés or coffeehouses. Recall that the Enlightenment not only gave Europe a new worldview but coffee and tea as well. It must have been considerably easier revolutionizing Western thought after morning coffee than after the typical medieval breakfast of beer and herring.

PUT-DOWNS AND PERSECUTIONS

The first persecutions of coffee and coffeehouses were undertaken on religious grounds, but subsequent attacks were more explicitly political. In 1511, the governor of Mecca tried to repress the very first coffeehouses because “in these places men and women meet and play violins, tambourines … chess … and do other things contrary to our sacred law.”

Similar attempts followed in Cairo, and the grand vizier of Constantinople ordered the coffeehouses of that city closed in the 1600s because, he said, they encouraged sedition. Caught drinking your first illegal cup of coffee, you got beaten with a stick; for the second, you got sewn in a leather bag and dumped in the Bosporus. Even such rigor failed to stop the coffee drinkers. Floating coffeehouses developed; enterprising people carried pots of the brew to serve secretly in alleys and behind buildings.

Charles II, Potency, and Politics

In 1675, King Charles II of England published an edict closing coffeehouses. The apparent pretext was an extraordinary document titled “The Women’s Petition Against Coffee, representing to public consideration the grand inconveniences accruing to their sex from the excessive use of the drying and enfeebling Liquor.” Conscientiously supporting their thesis with abundant examples of plentiful details, the authors contended that since becoming coffee drinkers, men had become “as unfruitful as the deserts from whence that unhappy berry is said to be brought,” and that as a consequence “the whole race is in danger of extinction.” The men rose to the occasion, however, with “The Men’s Answer to the Women’s Petition … vindicating their liquor from the undeserved aspersion lately cast upon them, in their scandalous pamphlet.”

However concerned he may have been with questions of virility, Charles II revealed his true preoccupation in the wording of his proclamation: “In such Houses … divers False, Malicious and Scandalous Reports devised and spread abroad, to the Defamation of his Majestie’s Government, and to the Disturbance of the Peace and Quiet of the Realm.”

The reaction among coffee lovers was pronounced and immediate, and only eleven days later Charles II published a second edict withdrawing his first: “An Additional Proclamation Concerning Coffee Houses,” which declared that he had decided to allow coffeehouses to stay open out of “royal compassion.” Some observers cite this turnaround as a record for the most words eaten in the shortest time by any ruler of a major nation, unsurpassed until modern times.

A WORLDWIDE TRADITION

The tradition of the coffeehouse has spread worldwide. Australia is paved with Italian-style caffès and Japan has evolved its kisatens, an elegant interpretation of American 1950s-style coffee shops and coffeehouses. In Great Britain, the espresso-bar craze of the 1950s came and went but is in the midst of a Starbucks-style comeback. Other parts of Europe and the Middle East have their own ongoing traditions. In Vienna, the home of some of the first European coffeehouses, the café tradition has undergone a renaissance.

In the United States, the 1930s and ’40s brought the classic diner, and the 1950s and ’60s the vinylboothed coffee shop, together with the coffeehouse—haunt of rebels, poets, beboppers, and beatniks. All of these incarnations are still with us. The classic diner is enjoying a revival, coffee shops still minister to the bottomless cup, and in American cities hundreds of new coffeehouses cater to a fresh generation of rebels, complete with funky furniture, radical posters, jazz, and folksingers.

But the 1970s and ’80s appear to have produced still another North American café tradition. Classic Italian-American caffès of the 1950s, like Caffè Reggio in Manhattan and Caffè Trieste in San Francisco, appear to have influenced the development of a style of café or caffè that takes as its starting point an immigrant’s nostalgic vision of the lost and gracious caffès of prewar Italy. From that vision come the light and spacious interiors of the new North American urban café, together with the open seating, the simple and straightforward furnishing, and an atmosphere formal enough to discourage customers from swaggering around and putting their feet on chairs, yet informal enough to mix students doing homework and executives having business meetings. Add an espresso machine and some light, new American cuisine, and the latest version of the American café is defined.