2 HOW IT STARTED

Dancing (and nondancing) goats

Coffee’s economic paradox

Coffee snobs to the rescue

The favorite story about the origin of coffee goes like this: Once upon a time in the land of Arabia Felix (or in Ethiopia, if an Ethiopian is telling the story) lived a goatherd named Kaldi. Kaldi was a sober, responsible goatherd whose goats were also sober, if not responsible. One night, Kaldi’s goats failed to come home, and in the morning he found them dancing with abandoned glee near a shiny, dark-leafed shrub with red berries. Kaldi soon determined that it was the red berries on this shrub that caused the goats’ eccentric behavior, and soon he was dancing too.

Finally, a learned imam from a local monastery came by, sleepily, no doubt, on his way to prayer. He saw the goats dancing, Kaldi dancing, and the shiny, dark-leafed shrub with the red berries. Being of a more systematic turn of mind than the goats or Kaldi, the learned imam subjected the red berries to various experimental examinations, one of which involved parching and boiling. Soon, neither the imam nor his fellows fell asleep at prayers, and the use of coffee spread from monastery to monastery throughout Arabia Felix (or Ethiopia) and from there to the rest of the world.

Goats Put to the Test

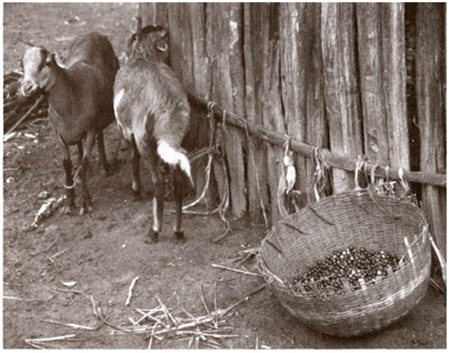

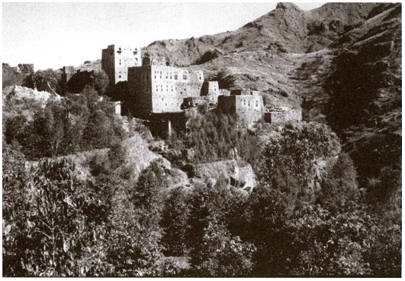

Some centuries later, in 1998, I was visiting coffee farms in the mountains of Yemen, the home of Kaldi in the Arabia Felix version of the story. Central Yemen is an austerely beautiful landscape of steep, terraced mountains and stone villages. Yemen coffee is still produced in the simple, direct way it was hundreds of years ago, and it remains one of the finest of the world’s coffees. I was curious about the Kaldi story, however, and persuaded a goatherd to bring his goats into a coffee orchard. After having set up a video camera to document this dramatic reenactment of coffee myth, I asked the goatherd to offer the goats fresh coffee branches festooned with ripe coffee fruit.

The goats sniffed the coffee branches suspiciously, then began to munch some miserable dried grass growing around the foot of the trees.

I tried the same experiment later with what were advertised as much hungrier goats. This time I offered them three choices: fresh coffee branches, dry grass, and qat tree leaves, which Yemenis chew in the afternoon for their stimulant properties. Goat preference sequence: qat leaves number one, dry grass number two, coffee three.

Perhaps the goats I tried were just being perverse, as goats will. Perhaps myths are not supposed to be tested, only told. And I need to add that on a recent trip to Ethiopia I did see some goats happily munching on fresh coffee leaves a woman was feeding them. Perhaps Ethiopian goats are more prone to coffee eating than Yemeni goats, which could be taken as a goat vote for the Ethiopian claim that Kaldi was their goatherd not the Yemeni’s.

Europeans Make the Wrong Assumption

In any event, Europeans initially assumed coffee originated in Yemen, near the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula, where Europeans first found it cultivated. But botanical evidence indicates that Coffea arabica, the finest tasting of the hundreds of species of coffee and the one that hooked the world on coffee, originated on the plateaus of central Ethiopia, several thousand feet above sea level. It still grows there wild, shaded by the trees of the rain forest.

How it got from Ethiopia across the Red Sea to Yemen is uncertain. Given the proximity of the two regions and a sporadic trading relationship that goes back to at least 800 B.C., no specific historic event needs to have been involved. But if one were to be cited, the leading candidate would appear to be the successful Ethiopian invasion of southern Arabia in A.D. 525. The Ethiopians ruled Yemen for some fifty years, plenty of time for a minor bit of cultural information like the stimulant properties of a small red fruit to become part of Yemeni experience and, eventually, its agricultural practices.

At any rate, Coffea arabica seems to have been cultivated in Yemen from about the sixth century on. It seems likely that cultures in the Ethiopia region cultivated the tree before it was transported to Yemen, but probably more as a kind of medicinal herb than as source of the beverage we know as coffee.

COFFEE CIRCUMNAVIGATES THE GLOBE

In Arabia coffee was first mentioned as a medicine, then as a beverage taken by Sufis in connection with meditation and religious exercises. From there it moved into the streets and virtually created a new institution, the coffeehouse. Once visitors from the rest of the world tasted it in the coffeehouses of Cairo and Mecca, the spread of Coffea arabica, by sixteenth-century standards, was extremely rapid.

The amazing odyssey of the arabica plant was possible only because of its stubborn botanical self-reliance. It pollinates itself, which means mutations are much less likely to occur than in plants that have a light pollen and require cross-fertilization. Most differences in flavor between arabica beans probably are caused, not so much by differences in the plants themselves, but by the subtle variations created by soil, moisture, and climate. The plant itself has remained extraordinarily true to itself through five centuries of plantings around the world.

Legend proposes that the Arabs, protective of their discovery, refused to allow fertile seed to leave their country, insisting that all beans first be parched or boiled. This jealous care was doomed to failure, however, and it was inevitable that someone, in this case a Muslim pilgrim from India named Baba Budan, should sneak some seeds out of Arabia. Tradition says that sometime around 1650, he bound seven seeds to his belly, and as soon as he reached his home hermitage, a cave in the hills near Chickmaglur in southern India, he planted them and they flourished. In 1928, William Ukers reported in his encyclopedic work All About Coffee that the descendants of these first seeds “still grow beneath gigantic jungle trees near Chickmaglur.” Unfortunately, they do not grow there any longer, although the site has become something of a destination for twentieth-century coffee pilgrims.

The French, Dutch, and Portuguese all became interested in the money-making potential of coffee cultivation, but various attempts to propagate coffee in Europe failed because the coffee tree does not tolerate frost. The Dutch eventually carried coffee, perhaps the descendants of the first seven seeds of Baba Budan, to Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and then to Java, where, after some effort, coffee growing was established on a commercial basis at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

At this point in history, coffee made its debut as the everyday pleasure of nobles and other Europeans rich enough to afford exotic luxuries. Coffee was available either from Mocha, the main port of Yemen, or from Java. Hence the famous blend of Mocha Java, which in those days meant putting together in one drink the entire world of coffee experience.

The Wayfaring Tree

Now comes one of the most extraordinary stories in the spread of coffee: the saga of the noble tree. Louis XIV of France, with his insatiable curiosity and love of luxury, was of course by this time an ardent coffee drinker. The Dutch owed him a favor and managed, with great difficulty, to procure him a coffee tree. The tree had originally been obtained at the Arabian port of Mocha, then carried to Java, and finally back across the seas to Holland, from where it was brought overland to Paris. Louis is said to have spent an entire day alone communing with the tree (probably thinking about all the money coffee was going to make for the royal coffers) before turning it over to his botanists. The first greenhouse in Europe was constructed to house the noble tree. It flowered, bore fruit, and became one of the most prolific parents in the history of plantdom.

This was 1715. From that single tree sprang billions of arabica trees, including most of those presently growing in Central and South America. But the final odyssey of the offspring of the noble tree was neither easy nor straightforward.

Coffee Hero de Clieu

The first sprouts from the noble tree reached Martinique in the Caribbean in about 1720, due to the truly heroic efforts of Chevalier Gabriel Mathieu de Clieu, who follows Baba Budan into the coffee hall of fame. De Clieu first had difficulties talking the authorities in Paris into giving him some trees (he finally stole them), but this was nothing compared with what he went through once at sea. First, a fellow traveler tried to rip up his trees, a man who, de Clieu writes, was “basely jealous of the joy I was about to taste through being of service to my country, and being unable to get this coffee plant away from me, tore off a branch.” Other, more cynical, commentators suggest the potential coffee thief was a Dutch spy bent on sabotaging the French coffee industry.

Later, the ship barely eluded pirates, nearly sank in a storm, and was finally becalmed. Water grew scarce, and all but one of the precious little seedlings died. Now comes the most poignant episode of all: de Clieu, though suffering from thirst himself, was so desperately looking forward to coffee in the New World that he shared half of his daily water ration with his struggling charge, “upon which,” he writes, “my happiest hopes were founded. It needed such succor the more in that it was extremely backward, being no larger than the slip of a pink.”

Once this spindly shoot of the noble tree reached Martinique, however, it flourished. Fifty years later there were 18,680 coffee trees in Martinique, and coffee cultivation was established in Haiti, Mexico, and most of the islands of the Caribbean.

De Clieu became one of coffee’s greatest heroes, honored in song and story (songs and stories of white Europeans, that is; what the African and Indians working the new coffee plantations thought about coffee is not recorded). Pardon, in La Martinique, says de Clieu deserves a place in history next to Parmentier, who brought the potato to France. Joseph Esménard, a writer of navigational epics, exclaims:

With that refreshing draught his life he will not cheer;

But drop by drop revives the plant he holds more dear.

Already as in dreams, he sees great branches grow,

One look at his dear plant assuages all his woe.

The noble tree also sent shoots to the island of Réunion, in the Indian Ocean, then called the Isle of Bourbon. There, a combination of spontaneous mutation and human selection produced var. bourbon, a new variant or cultivar of Coffea arabica with a somewhat different pattern and smaller beans. The famed Santos coffees of Brazil and the Oaxaca coffees of Mexico are said to be offspring of the bourbon tree, which had traveled from Ethiopia to Mocha, from Mocha to Java, from Java to a hothouse in Holland, from Holland to Paris, from Paris to Réunion, and eventually back, halfway around the world, to Brazil and Mexico. Trees of the bourbon variety continue to produce some of Latin America’s finest coffees.

For the concluding irony, we have to wait until 1893, when coffee seed from Brazil was introduced into Kenya and what is now Tanzania, only a few hundred miles south of its original home in Ethiopia, thus completing a six-century circumnavigation of the globe.

A Billion-Dollar Bouquet

Finally, to round out the roster of coffee notables, we add the Don Juan of coffee propagation, Francisco de Mello Palheta of Brazil. The emperor of Brazil was interested in cutting his country into the coffee market, and in about 1727, sent Palheta to French Guiana to obtain seeds.

Like the Arabs of Yemen and the Dutch before them, the French jealously guarded their treasure, and Palheta, whom legend pictures as suave and deadly charming, had a hard time getting at those seeds. Fortunately for coffee drinkers, he so successfully charmed the French governor’s wife that she sent him, buried in a bouquet of flowers, all the seeds and shoots he needed to initiate Brazil’s billion-dollar coffee industry.

* * *

What is the larger economic and social meaning of coffee’s victorious march from obscure medicinal herb to the world’s most popular beverage? Here are three stories that propose very different visions of coffee’s impact on the world.

STORY 1: COFFEE AS THE WINE OF DEMOCRACY

The first story could be titled “How Coffee Created Western Civilization.” It runs like this: Before coffee insinuated its way into European life by way of contact with the Turks, Europe was run by morose aristocrats in impractical clothing sitting around drafty castles wasting their mental energy digesting breakfasts consisting of warm beer, bread, and other weighty, thought-inhibiting substances. Then came coffee, tea, and coffeehouses; and fueled by caffeine and light breakfasts, Europe was energized and transformed. In due course democracy, individualism, modern culture, and the specialty coffee industry were born, and castles were turned into museums (with café attached).

Obviously an overstatement, but one with basis in fact. When it comes to the events of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: the scientific revolution, the Enlightenment, and the subsequent political and social revolutions in France and present-day United States, a strong case can be made for the contribution of coffee and coffeehouses. In fact, it is difficult to find a major paradigm-breaking intellectual movement since about 1700 that was not associated with coffeehouses and coffee drinking, from the Enlightenment and Paris’s famous Procope, where Voltaire allegedly drank forty cups of coffee mixed with chocolate per day, to the coffeehouses of Addison and Steele’s London, through the French Revolution and the Café Foy, where Camille Desmoulins supposedly made the speech that started the crowd on its way to storming the Bastille, to Boston’s Green Dragon—according to Daniel Webster “the headquarters of the Revolution”—down to modern art movements, ranging from Dada through North America’s Beat movement, first nurtured in the coffeehouses of San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood.

Coffee or Coffeehouse?

Given the consistent association of coffeehouses with intellectual innovation and iconoclasm, we might ask whether the connection is due to the effects of coffee or simply to the institution of the coffeehouse itself, one of the few places where a broke intellectual can find a place to read, talk, and carry on against the establishment for the price of a cup of coffee.

The great French historian Jules Michelet obviously thought it was the coffee. Here is his rhapsodic tribute to coffee-besotted Paris of the eighteenth century:

Paris became one vast café. Conversation in France was at its zenith.… For this sparkling outburst there is no doubt that honor should be ascribed in part to the auspicious revolution of the times, to the great event which created new customs, and even modified human temperament—the advent of coffee.

Its effect was immeasurable.… The elegant coffee shop, where conversation flowed, a salon rather than a shop, changed and ennobled its customs.… Coffee, the beverage of sobriety, a powerful mental stimulant, which unlike spirituous liquors, increases clearness and lucidity; coffee, which suppresses the vague, heavy fantasies of the imagination, which from the perception of reality brings forth the sparkle and sunlight of truth; coffee anti-erotic …

I like to think that the reveries induced by caffeine are, as Michelet suggests, active and mental rather than emotional and sensuous, and so encourage an invidious comparison between what is and what could (or should) be.

STORY 2: COFFEE AS POISON OF THE TROPICAL POOR

There is, however, another coffee story. In this one coffee may have been the wine of democracy in Europe or North America, but for the rest of the world it was one more poison in the oppressive cup the developing world handed to the tropical poor to choke on for the next three hundred years.

Because, at the very historical moment that coffee-drinking intellectuals were shaking up politics and culture in Europe, floating the ideas that would turn into modern movements like abolition of slavery, socialism, and feminism, their more commercially inclined colleagues were setting up a global marketing machine. Together with sugar, tropical spices, and tobacco, coffee helped create history’s first world market with Europe as its consuming, decision-making, moneymaking hub. The same early plantation system that first produced sugar and tobacco later produced coffee for the elite of Europe, whether they hung out in palaces, like coffee-lover Louis XV, or in subversive coffeehouses, like Voltaire. Green coffee was a good cash crop for the new colonial entrepreneur. It stood up to long ocean voyages, had a splendid shelf life, and rapidly became one of those lucrative oxymorons, a necessary luxury.

The global economic network that was first created around sugar, coffee, tobacco, and other agricultural commodities is still with us, of course, the slaves of early coffee plantations having become free workers whose freedom largely consists of deciding whether to starve, work for a pittance, or head for the slums of the nearest big city.

A Few Chickens, Some Vegetables, and Coffee

Of course not all coffee is grown on large farms. Probably the majority of the world’s coffee is raised by what economists innocently term “small holders,” usually meaning a family in a shack on a couple of acres, augmenting a diet of chickens and vegetables with a little cash from coffee sold either to government agencies at predetermined prices or to smalltime entrepreneurs cruising back roads in trucks (“coyotes” in Spanish-speaking Latin America), buying coffee for pennies a pound.

As poor as such small farmers may be, the fact that coffee early on escaped from the plantations and took root on the little plots of peasant farmers probably accounts for the fact that left-leaning historians have made it a lesser economic villain than, say, sugar, which is almost always grown on large farms or plantations.

Furthermore, coffee has entered the life and myth of many growing countries in such a fundamental way that it has become a difficult whipping boy. Poor Latin Americans, for example, love their coffee as much as Voltaire loved his, perhaps more so. This love is shared by the intellectual leaders of the Latin-American left, who are as reluctant to brand coffee an economic villain as North Americans might be to blame Santa Claus for materialism. I am told by Colombians, for example, that representatives of the National Federation of Coffee Growers of Colombia can pass as freely through rebel-held areas of Colombia as they do through those controlled by the government.

Nevertheless, from those forty cups that Voltaire drank at the Café Procope to the cup that Allen Ginsberg drank at the Caffè Trieste in 1956 to the caffè latte that you drank just yesterday, coffee has figured in exactly the sort of nasty economic exploitation that Voltaire, Allen Ginsberg, and (probably) you deplore.

So where does this leave coffee? Politically correct? Incorrect? Or just the usual don’t-think-about-it-it’s-too-complex kind of modern issue?

STORY 3: COFFEE SNOBS TO THE RESCUE

At this point a third history of coffee proposes itself, one that is closely linked with the theme of this book.

Until not very long ago, raw or “green” coffee beans arrived in North American ports wrapped in burlap and mystery. Most coffee was sold bulked in large lots according to various grading and market categories, its price driven by the same relentless (and faceless) supply-and-demand forces that have assured hard times for small (and often large) coffee growers ever since the eighteenth century. Even the dealers and roasters involved in the fledgling specialty coffee business of twenty-five years ago, when I researched the first edition of this book, seldom met a living, walking, talking coffee grower. They bought coffees based on how samples tasted, and they identified coffees in the often enigmatic language of the stencils on the burlap bags: Sumatra Lintong, Yemen Mocha Sanani, Mexico Oaxaca Pluma, Brazil Santos. No one even knew for certain what the more obscure of these traditional terms meant in regard to growing location and conditions. Gourmet coffee was a drama played out in the cup, rather than on the larger stage of the world and its social and economic issues.

The few coffees that did escape the impersonal leveling of the market and sold for a premium, like the famous Wallensford Estate Blue Mountain, did so on the basis of myth rather than direct contact between buyer and grower.

Global Market to Global Community

Now, however, a global coffee community has grown up around the global coffee market. And changes in how coffee is retailed and consumed means that coffees once buried in the general production of a country, continent, or region can be isolated and marketed separately, demanding a higher price per pound based on an interplay of factors ranging from the quality of the coffee to how it was grown (organically, sustainably, in the shade rather than in the sun) to how persistent a global networker the grower happens to be.

In 1950, North American coffee lovers had two choices for their Danish-modern-Chemexes: a cheap blend of coffees or a more expensive blend of coffees. The identity of the coffees making up either alternative and whatever human and gustatory stories lay behind them were lost in the vast apparatus of the market. To be fair, there was a third choice: Somewhere along the way Juan Valdez emerged from the coffee trees of Madison Avenue toting cans of Colombian coffee on the back of his well-groomed donkey. Colombia successfully positioned itself as the only unblended, single-origin coffee widely available in cans.

Today, however, those North American coffee enthusiasts, assuming they live in or near a large city, can choose from an enormous array of coffees whose human, botanical, and ecological stories are increasingly clear and accessible, at least for those willing to stop a moment and listen. And the expressive possibilities available to the coffee lover in turn create opportunities for the coffee grower.

Village in the 72heart of the Bani Mattar coffee-growing region of Yemen.

Commodity to Delicacy

I once sat on a committee of the Specialty Coffee Association of America, an industry association considerably (and increasingly) more international than its name implies, across from Jaime Fortuño, a bright and amiable young man who, with his wife, Susan, was leading a revival of Yauco, a once famous coffee from Puerto Rico.

Puerto Rico had stopped importing coffee years ago. Labor costs were too high in Puerto Rico for its coffees to compete in a global market driven largely by price, and Puerto Rico, like most of the rest of the coffee-growing countries of the world, could hardly afford an advertising campaign of the scope Colombia mounted to glamorize Colombia coffee and elevate its price.

However, taking advantage of the opportunities provided by the new American specialty coffee market, Jaime was able to work with other bright, amiable young men and women both in Puerto Rico and the United States, including the green coffee dealer David Dallis of New York City, to create a small, particularized market niche for coffees from a group of Puerto Rican farms. This revived Puerto Rico coffee not only would have been lost in the old, undifferentiated coffee market of thirty years ago, but it would not have existed in the first place, since the specialized market did not exist to support it and the high cost of growing it.

The farmers whom Jaime and Susan represent use the higher price their coffee commands to pay their workers better and take certain steps to ameliorate the environmental impact of their growing and processing endeavors. The environmental and social correctness of their coffee further justifies its higher price to environmentally and socially aware coffee lovers.

The Small-Holder Strategy

But what about the “small holders,” the folks with their vegetables, chickens, and a few coffee trees up the hill? A variation of the same strategy is working for them, or at least for some of them. Cooperatives of small growers now market their coffees directly to sympathetic coffee dealers and roaster-retailers, exactly as Jaime Fortuño did with his coffee. Consumers can buy coffees produced by cooperatives of small growers located in places as various as Chiapas, Mexico; Haiti; northern Peru; Papua New Guinea; and East Timor. Furthermore, these small holders often hold an edge over larger farms in getting their coffees certified as organically grown, since they were never able to afford chemicals in the first place. By certifying their coffees as organically grown and identifying them as economically progressive, the small-grower cooperatives are able to separate their coffees from the crowd and obtain a higher price for them, a good deal of which actually makes it back to the growers rather than being swallowed up by exporters and dealers.

I do not want to make all of this sound more hopeful than it actually is. Most of the coffee of the world still gets fed into the faceless maw of the larger global market and comes out at the other end packed in cans, bricks, or glass jars. Many owners of larger farms attempting to take advantage of new, individualized marketing arrangements are substituting fancy brochures and hype for good coffee or may choose to spend the premium their coffee commands on mechanization or on themselves rather than on better wages and living conditions for their workers and more sustainable agricultural practices. Cooperative marketing efforts by associations of small growers often run into problems created by lack of capital and unfamiliarity with the North American market and its expectations.

Neverthless, it is clear that the economic paradox of coffee and the old faceless relationships that supported it are dissolving in new and unpredictable ways.

Today, Voltaire would have E-mail, a fax, and a good travel agent. More to the point, his coffee dealer would have them too. Voltaire was a sincere humanist and cosmopolitan and probably would have chosen to drop a few extra francs a year on a coffee from, say, a cooperative in Chiapas. But even if he found himself too distracted writing famous books and entertaining amusing people to pay attention to coffee politics, his palate would have made him a coffee progressive despite himself. Voltaire, I am sure, would always have his servants buy Puerto Rico Yauco Selecto in preference to generic in a can.