7 ROASTING IT

How coffee is roasted

Formula vs. eye, ear, and nose

How to roast your own

Since we have come to associate the word coffee so absolutely with a hot, aromatic brown liquid, some may find it hard to believe that human beings apparently waited for several hundred years before concluding that the most effective way to get what they wanted from the coffee tree was to roast the dried kernel of the fruit, grind it, and combine the resulting powder with hot water to make a beverage. The alternative solutions are many, and some apparently still survive as part of the cuisines of Africa and Asia. The berries can be fermented to make a wine, for example, or the leaves and flowers cured and steeped in boiling water to produce a coffee-tea. In parts of Africa, people soak the raw beans in water and spices, then chew them like candy. The raw berries are also combined with bananas, crushed, and beaten to make a sort of raw coffee and banana smoothie.

In Yemen, where coffee was first cultivated as a commercial crop, the husks of the dried coffee fruit are boiled with spices to produce a sweet, light beverage called qishr. It is served cool as a thirst quencher in the afternoon, much as we might serve iced tea.

The key to the success of the current mode of coffee making is the roasting process, to which we owe the delicately flavored oils that speak to the palate as eloquently as caffeine does to the nervous system. “The coffee berries are to be bought at any Druggist,” says a seventeenth-century English pamphlet on coffee drinking, “about three shillings a pound; take what quantity you please and over a charcoal fire, in an old pudding pan or frying pan, keep them always stirring till they be quite black, and yet if you exceed, then do you waste the Oyl, which only makes the drink; and if less, then will it not deliver its Oyl, which must make the drink.”

We may disagree with the Englishman’s taste in roasting (“quite black” sounds more Neapolitan than English), but he knew what counted: the breaking down of fats and carbohydrates into an aromatic, volatile, oily substance that alone produces the essential coffee flavor and aroma. Without roasting, the bean gives up its caffeine and acids, and even its protein, but not its flavor.

THE ROAST TRANSFORMATION

The chemistry of coffee roasting is complex and still not completely understood. This is owing to the variety of beans, as well as to the complexity of the coffee essence, which still defies chemists’ best efforts to duplicate it in the laboratory.

Much of what happens to the bean in roasting is interesting but irrelevant. The bean loses a good deal of its moisture, for instance, which means it weighs less after roasting than before (a fact much lamented among penny-conscious commercial roasters). It loses some protein, about 10 to 15 percent of its caffeine, and traces of other chemicals. Sugars are caramelized, which contributes color, some body, and sweetness, complexity, and flavor to the cup.

Roasting is simple in theory: The beans must be heated, kept moving so they do not burn or roast unevenly, and cooled, or quenched, when the right moment has come to stop the roasting. Coffee that is not roasted long enough or hot enough to bring out the oil has a pasty, nutty, or breadlike flavor. Coffee roasted too long or at too high a temperature is thin-bodied, burned, and industrial-flavored. Very badly burned coffee tastes like old sneakers left on the radiator. Coffee roasted too long at too low a temperature has a baked flavor.

During the early part of the roast, the bean merely loses free moisture, moisture that is not bound up in the cellular structure of the bean. Eventually, however, the deep-bound moisture is forced out, expanding the bean and incidentally producing a snapping or crackling noise. So far, the color of the bean has not changed appreciably (it should be a light brown), and the oil has not been volatilized. Then, when the interior temperature of the bean reaches about 370°F, the oil suddenly begins developing. This process is called pyrolysis, or volatilization, and it is marked by darkening in the color of the bean.

At some point after pyrolysis sets in, but before the bean is terminally burned, the moment of truth arrives for the roastmaster, because the pyrolysis of the coffee essence must be stopped at precisely the right moment to obtain the degree of roast and associated flavor desired. The beans cannot be allowed to cool of their own accord or they may overroast. With smaller-scale equipment the cooling may be managed by fans that pull room-temperature air through the hot beans while they are stirred, a procedure called air quenching. Larger roasting machines may permit the roast-master to water-quench the beans, or kick off the cooling process with a brief spray of water. If the water quenching is done properly and discreetly, the water evaporates immediately from the surface of the hot beans and does not adversely affect the flavor of the coffee. In fact, coffee that has been correctly water-quenched often tastes better than air-quenched coffee because the cooling is more decisive.

ROASTING EQUIPMENT

When delivered to the roaster in burlap sacks, the coffee bean ranges in color from light brown to whitish green to a lovely bluish emerald green. The beans are always stored in their raw, or green, state. Roasted whole beans begin to deteriorate in flavor within days after roasting, and ground coffee may taste stale within an hour of grinding; whereas green coffee, stored in cool, dry, well-ventilated conditions, remains stable for years.

The exact nature of the equipment used to roast coffee depends on the ambitions of the roaster. Most large commercial roasters resemble a gigantic screw rotating inside a drum. The screw works the coffee down the drum; by the time the coffee reaches the end of the drum, it is roasted and ready to be cooled by air or water. The temperature is controlled automatically, and the roaster includes equipment that monitors both the air temperature and the temperature inside the moving mass of beans to monitor their progress. Such roasters are called continuous roasters for obvious reasons and are inappropriate for specialty coffee roasting because they cost too much, roast too much coffee at a time, and cannot be easily stopped to reload with new and different kinds of coffee.

The average specialty roaster uses a batch roaster, which simply means any machine that roasts a batch of coffee at a time rather than the same coffee for most of the day. The most common design of batch roaster consists of a rotating drum above a heat source, usually a gas flame. Operating like a Laundromat clothes drier, the rotating drum tumbles the beans, ensuring an even roast, while convection currents of heated air move through the drum. Drum roasters may be as large as five or six feet in diameter, or as small as a small waste can set on its side.

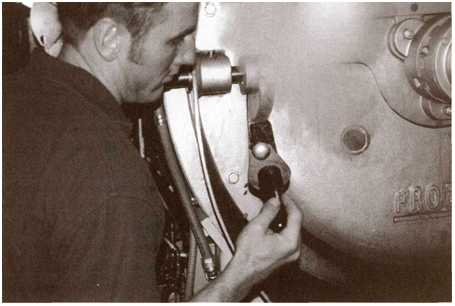

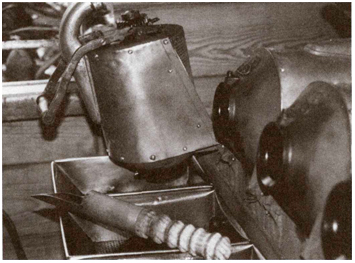

To the right is an illustration of the simplest kind of small drum roaster. The drum (A) tumbles the roasting coffee over the gas flame (B). The fan (C) sucks the smoke and chaff out of the drum. When the beans are dumped into the cooling box (D), ready to be quenched, the fan is reversed, and cool air is forced through the hot beans in the box.

More sophisticated batch roasters retain the basic structure of drum, heat, and cooling box, but may use a stronger current of hot air to heat the beans, so that the metal drum itself remains relatively cool. These are sometimes called convection roasters. Another kind of recently developed batch roaster uses radiant heat panels on either side of the drum. Some contemporary roasters, called fluidized-bed roasters, carry the hot air principle of convection roasters even further by dispensing with the drum entirely and agitating the beans with a column of hot air, much as an electric popcorn popper does with corn kernels.

In all cases, the goal of the technology is to offer the operator maximum control over the process, and to keep the beans from touching hot metal for anything longer than a split second at a time to prevent scorching or uneven roasting. Proponents of the various styles of batch roaster all make cogent arguments for their favored system and in mild deprecation of rival approaches, but to my knowledge no conclusive comparative tests have ever been conducted to validate any of these claims and counterclaims. In my observation and experience, all batch-roasting apparatus, including the oldest and crankiest, can produce outstanding coffee if used with care and knowledge.

The simplest kind of small, traditional drum coffee roaster. The drum (A) tumbles the roasting coffee over the gas flame (B). The fan (C) maintains a convection current of hot air through the drum that carries away smoke and chaff. When the roast is ready to be terminated, the hot beans are dumped into the cooling box (D) where the fan pulls room temperature air through them.

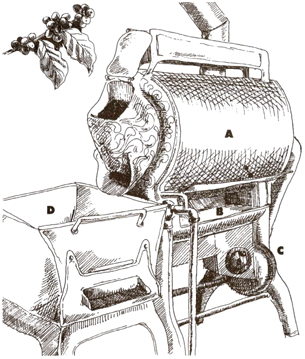

John Weaver of Peet’s Coffee & Tea watches just-roasted beans tumble out of roasting drum into cooling tray.

A battery of small drum roasters used to prepare coffee samples for cupping, Old Tavern Estate, Jamaica.

ROASTING PROCEDURE: FORMULA VS. EXPERIENCE

Roastmasters tend to fall into two schools: technical roasters, who follow a system involving precisely defined and monitored variables like time and temperature, and craft roasters, who depend mainly on eye, ear, nose, and accumulated experience.

Roasting by Instrument

The key to technical roasting is an electronic thermometer or heat probe designed to rest inside the bed of beans as they roast. Since degree or darkness of roast precisely reflects the internal temperature of the roasting beans (think of the thermometers you stick into roasting turkeys or meat), the heat probe permits the roast-master to follow the development of the roast inside the machine with confidence. A second heat probe registers the temperature of the air inside the roasting chamber. The roastmaster, using various formulas that define the optimum relationship between these two temperatures plus information regarding air velocity inside the roasting chamber, profiles the roast, adjusting temperature ratios and air velocity to control the intensity of the pyrolysis and the length of the roast. And, I might add, profoundly influencing how the coffee eventually tastes, because two batches of the same coffee roasted to exactly the same degree of roast but using two different profiling strategies will taste dramatically different.

Roasting by Eye, Ear, and Nose

Craft roasters also profile coffees, adjusting temperature and air velocity inside the roasting chamber as the roast progresses. However, their adjustments are based not on formula but on long experience with roasting generally, with roasting specific coffees, and with the peculiarities of their machines.

Internal bean temperature is not the only way to tell what is going on inside a roasting machine. Roasting coffee signals its internal changes by a number of rather dramatic external signs. As well as changing in color, roasting coffee speaks to the roaster by emitting a crackling sound at two very predictable moments in its development—the “first crack” when pyrolysis begins, and the “second crack” when the woody matter of the bean begins to transform and the beans start to enter the pungent, bittersweet realm of darker roasts. When craft roasters speak about a specific green coffee and how to roast it, for example, they speak in terms of the crack—just before the second crack, just at the second crack, just into the second crack, well into the second crack, and so on.

The changing smell of the roasting smoke also tracks the development of the roast, starting with a bready smell before the first crack, to a fuller, sweeter, more rounded scent between the first and second cracks, to a pungent, sharper, oilier odor during the second crack. The best old-time craft roasters can control the roast quite accurately based on the smell of the roasting smoke alone.

Neither technical roasters with their thermometers and formulas nor craft roasters with their eye, ear, nose, and accumulated experience necessarily produce the best coffee. But both produce far better coffee than people who “just roast ’em till they’re brown,” or relative newcomers who think they are craft roasters but are not. True craft roasting demands long training and experience. The average accountant or English major with no coffee experience who decides to open a store and roast coffee is best served by taking a seminar on technical roasting and installing a heat probe in his or her new roasting machine.

A CRAFT ROASTER REMEMBERED

As for a craft roaster of the old school, I recall the old Graffeo coffee shop in San Francisco, locally famous for its rich, sturdy espresso coffee. In years past, Graffeo coffee was roasted in a small, old-fashioned batch roaster by John Repetto, the father of the present proprietor and a craft roaster if there ever was one.

Three open bags of green coffee stood next to the roasting machine. Two contained coffees from South and Central America, one with lighter and the other with heavier body. The third bag was a mix of several bright, distinctively flavored coffees: Yemen Mocha, Kenya, or Ethiopia Yirgacheffe, for instance. Repetto would nonchalantly scoop almost equal parts of each into the rotating drum of the roasting machine, close the door, and turn up the flame. He then wandered around the store, waiting on customers and following this timetable, which anyone who roasts coffee at home would be wise to follow as well:

1. Coffee smells like the sack (do something else for a while).

2. Coffee smells like bread (do something closer to the roaster).

3. The beans begin to crackle (prepare for action).

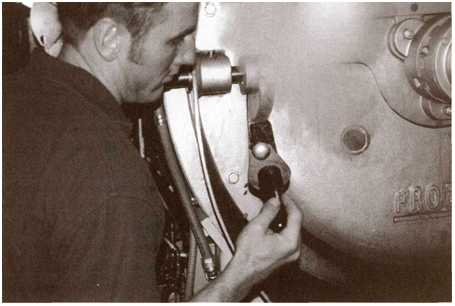

When he heard the beans crackle, Repetto would begin to check the color of the beans by collecting a few with a little spoonlike implement called a trier, which he stuck through an opening in the front of the roasting cylinder. He also sniffed the odor of the beans that wafted from the trier and kept his ear open for the second crack.

Just into the second crack, when the color was medium dark brown (the shop sold and still sells mainly dark-roast coffee), he opened a door in the cylinder and the beans tumbled out into the box in front of the roaster. The roasting continued inside the steaming, crackling beans for a moment or two while Repetto stirred them and studied them for color. When they were dark brown (“the color of a monk’s tunic”), he tripped a lever on the side of the fan box, forcing cold air up through perforations at the bottom of the box to conclude the roast.

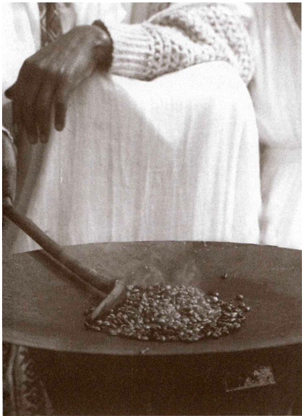

Roasting coffee in Ethiopia for a village coffee ceremony.

Some Years Later …

Much excellent specialty coffee is still roasted in similarly informal fashion in similarly charming old machines. I recall revisiting the Graffeo shop, however, and finding the old roasting machine holding up plants in the store window while John’s son, Luciano, wearing a white smock, watched dials on the front of a chrome box.

I recognized this box as a Sivitz roaster, the creation of Michael Sivitz, a well-known coffee researcher and technical writer who had gone into the business of producing his own roasting equipment based on the fluidized-bed principle mentioned earlier, a principle that Sivitz pioneered. Rather than rotating the beans inside a cylinder, fluidized-bed machines use a powerful column of hot air to both roast and agitate the beans. Sivitz also was one of the pioneers of technical roasting in the United States and one of the first to install heat probes in small batch roasters.

Coffee from the Sivitz machine with its heat probe tasted good, and so did coffee from the old machine. The uniting principle here is that both John and Luciano cared about what they were doing and roasted with tact and precision.

ROASTING AT HOME

Those who want to be certain their coffee is fresh—in fact, anyone who wishes to drink the best cup of coffee possible—may want to experiment with roasting coffee at home. Home roasting takes about as much time and skill as cooking spaghetti and is considerably simpler than other, more fashionable back-to-basics activities, such as baking bread or making beer. Any small mistakes in the roasting process are far offset by the advantages of freshness.

Ground, roasted coffee is actually as much a convenience food as instant coffee or frozen foods are. Americans roasted their own coffee until the late-nineteenth century, and many people all over the world still do. Jabez Burns, inventor of the continuous roaster, the first modern production roaster, insisted that some of the best coffee he ever tasted was roasted in a corn popper. On a recent visit to the Ethiopian countryside I was treated almost daily to servings of coffee that had been roasted on the spot in shallow pans over coals, and that coffee, despite what appeared to be a scattering of black, overroasted beans, invariably tasted superb.

Home-Roasting Methods

The physical requirements for roasting coffee correctly are very simple: the coffee needs to be kept moving in air temperatures of at least 400°F and must be cooled at the right moment. There are many ways to meet these requirements in home kitchens, which can be divided into four main approaches: (1) in the oven; (2) on top of the stove; (3) in a hot-air popcorn popper; and (4) in a small, commercially produced, electric home roaster. Those who wish to experiment with one of the first three methods should purchase my Home Coffee Roasting: Romance & Revival, also published by St. Martin’s Press. I give detailed instruction for each method and advise on improvising equipment.

Here, however, are a few words of advice and instruction in regard to the fourth and easiest alternative, commercially produced, home-roasting machines. Most of these devices work on the fluidized-bed principle, meaning the beans are simultaneously heated and agitated by a column of hot air jetting up through the roasting chamber.

Three Home-Roasting Machines

At this writing three such devices are on the market, retailing from $100 to $140: the Fresh Roast Coffee Bean Roaster, Hearthware Gourmet Coffee Roaster, and Hearthware Precision Coffee Roaster. If you have difficulty finding a source for these devices, see Sending for It. All are easy to use, though they roast a relatively small volume of beans per session. All incorporate a glass roasting chamber, enabling you to observe the changing color of the beans; a chaff collector at the top or back of the roasting chamber to prevent the brown flakes that roasting removes from coffee beans from blowing around the kitchen; and an adjustable timer, which controls the length of the roast by automatically triggering a cooling cycle. The controls for the Hearthware Gourmet and Fresh Roast units allow the user to manually override the timer, an important feature.

The Tricky Part: Timing the Roast

The only trick with these devices is to learn when to stop the roast to get the darkness of roast and hence the taste you prefer. The longer the green beans roast, the darker the color and the deeper and less bright the taste. Because batches of green coffee beans differ from one another in density and moisture content, it is impossible for the manufacturers (or for me) to specify exact roasting settings or times.

The Experimental Approach

One way to approach timing the roast is to roast a batch of beans on the Medium setting, brew the result, and fine-tune the setting from there for subsequent batches, based on whether you want a sweeter, richer, more pungent taste (set the timer for a longer roast) or a brighter, drier, brisker taste (set the timer for a shorter roast).

When you arrive at a setting that produces a roast that satisfies you, make a note of it. You should be able to set the timer to the same point and obtain similar results for subsequent roast sessions. However, every time you buy a new batch of green beans you probably will need to experiment again, modifying the setting slightly to produce your preferred roast color and taste. Decaffeinated beans and aged beans, both of which start out brown and roast either very quickly (decaffeinated beans) or very slowly (aged beans), may require particularly watchful experimentation to obtain a satisfactory roast.

The Imitate-the-Color Approach

Another, less hit-or-miss approach involves putting a handful of beans from a coffee store roasted to the degree or color you prefer on the counter next to the machine. You then start the roast at the maximum Dark setting, watch the raw beans through the glass as they roast until they are just slightly lighter than your sample beans, and at that point manually override the timer by advancing the timing dial to Cool or by pushing the appropriate roast-stopping button.

With some particularly dense or moist beans you may need to turn the timing dial back (or add time to the roast cycle with digitally controlled models) to prolong the roast long enough to achieve the darkness of roast you favor. One of the three currently available fluidized-bed devices, the Fresh Roast, has a switch that slightly increases the heat in the roasting chamber to facilitate achieving darker roasts. When using the Fresh Roast, I suggest you start your roasting experiments by placing this switch on the Dark setting and the timer on Medium. If, after tasting the resulting roast, you want a brighter, drier, brisker taste, move the switch to Light.

Again, after you have determined the right length of time to roast a given batch of beans to the style you prefer, you should be able to set the timer and walk away for subsequent roast sessions. Nevertheless, you probably still will need to hover over the roaster once again to determine the appropriate setting when you buy a new batch of beans. Again, decaffeinated beans and aged beans require particular attention.

Buying Green Coffee

All home-roasting machines come with order forms for green beans. Internet sites provide additional sources for green beans, including very exotic origins. If you need help finding an appropriate site, see Sending for It. Consult Chapter 5 for more on choosing beans by origin and blending them.

After the Roast

Always remove freshly roasted beans from the machine immediately after the cooling cycle has concluded. Leaving beans in a still-warm roasting chamber will dull taste. Freshly roasted coffee is at its best if it is allowed to rest for about twenty-four hours after roasting, permitting the recently volatilized oils to stabilize. If you are impatient or needy, however, grind immediately and enjoy.

Home-Roasting Precautions

Coffee roasting produces smoke. This smoke presents two problems: It can set off smoke alarms if not ventilated, and however pleasant it smells during roasting, it clings and becomes cloying over the long run. Always set up your home-roasting machine under the hood of your range and turn on the fan. In clement weather you can roast out-of-doors on porch or patio.

A second precaution: Always use exactly the volume of beans recommended by the manufacturer of your roasting device. Too many or too few beans may not agitate properly and may roast unevenly.