9 BREWING IT

Choosing a method and a machine

Brewing it right

No matter what we call them, all ways of brewing coffee are basically the same: the ground coffee is soaked in the water until the water tastes good. Nobody, to my knowledge, has figured out a different way to make coffee. The only equipment you really need to make great coffee is an open pot, a flame, and possibly a strainer.

THREE VARIABLES, THOUSANDS OF IDEAS

It is a tribute to human imagination and lust for perfection, however, that the simple act of combining hot water and ground coffee has produced so many ingenious variations and occupied so many brilliant people for uncounted hours over the past three centuries. Thousands of coffeemakers have been patented in the United States and Europe, but of this multitude only a handful have had any lasting impact or embodied any genuine innovation. The few ideas to achieve greatness can be divided according to three variables: how hot you make the water, how you get the water to the coffee, and how you separate the spent grounds from the brewed coffee.

Brewing Temperature

Until the eighteenth century, coffee was almost always prepared by boiling the water and grounds. Boiling, however, damages coffee flavor because it vaporizes much of the coffee essence while it continues to extract other bitter-tasting chemicals. The French began steeping, as opposed to boiling, coffee in the early eighteenth century, but this innovation did not penetrate the coffee-drinking mainstream until the nineteenth century and had to wait until the twentieth to triumph. Today, all American and European methods favor hot water (around 200°F), as opposed to boiling.

If boiling water has been universally rejected, cold water has not. You can steep coffee in cold water and get substantially the same results as with hot water. The only differences are that the process takes longer (several hours longer) and makes an extremely mild brew. Cold-water coffee is made concentrated and, like instant, is mixed with hot water.

Getting the Water to the Coffee

The second variable—how you get the water to the coffee—is a question of convenience. If you are not in a hurry, you might just as well heat the water and pour it over the coffee yourself. But if you want to do something else while the coffee is brewing, you might prefer the hot water to deliver itself to the coffee automatically. Furthermore, coffee making requires consistent and precise timing, a virtue difficult to maintain in this age of distractions. The advantage to machines is their single-mindedness; they make coffee the same way every time, even if the cell phone rings.

The Bubble Power of Boiling Water. One of the earliest efforts at automation was the pumping percolator, patented in 1827 by Frenchman Nicholas Felix Durant. The French ignored it, but the United States, the cradle of convenience, adopted it enthusiastically. The pumping percolator uses the bubble power of boiling water to force little spurts of hot water up a tube and over the top of the coffee. The hot water, having seeped back through the coffee, returns to the reservoir to mix with the slowly bubbling water at the bottom of the pot. The process continues until the coffee is brewed.

Ironically, the principle of the automatic filter drip, which was destined to supplant the pumping percolator in the United States starting in the 1970s, was patented a few months earlier than the percolator. Jacques-Augustin Gandais, a Parisian jewelry manufacturer, patented a device that sent the boiling water up a tube in the handle of the brewer and, from there, over the ground coffee. Gandais’s device even looks a bit like the first automatic, filter-drip brewers of the 1970s. It apparently was ignored for the same reason it was later enthusiastically adopted: It sent the water through the coffee only once, rather than repeatedly, as the pumping percolator did.

The Vacuum Principle. Around 1840, the vacuum principle in coffee brewing was simultaneously discovered by several tinkerers, including a Scottish marine engineer, Robert Napier. Napier’s original device looks more like a steam engine than a coffeemaker, but, as it has evolved today, the vacuum pot consists of two glasses globes that fit tightly together, one above the other, with a cloth or metal filter between them. The ground coffee is placed in the upper globe, and water is brought to a boil in the lower. The two globes are fitted together and the heat is lowered. Pressure develops as water vapor expands in the lower globe, forcing the water into the upper globe, where it mixes with the ground coffee. After one to three minutes, the pot is removed from the heat, and the vacuum formed in the lower globe pulls the brewed coffee back down through the filter.

Twentieth-Century Refinements. The twentieth century has brought us both the automatic electric percolator and the automatic, filter-drip coffeemaker, an improved electric version of Gandais’s 1827 device. In the automatic, filter-drip coffeemaker, the water is held in a reservoir above or next to the coffee, heated, and measured automatically over the ground coffee by the same bubble power that drives the percolator. The latest challenge to innovation in automated brewing is the microwave oven. The various (largely commercially unsuccessful) attempts at taking advantage of its unique technology have not broken new ground, however. The solutions proposed by appliance companies are all interesting variations on time-honored technologies, ranging from microwave oven pot to microwave vacuum and filter drip.

Separating Brewed Coffee from Grounds

Now we reach the brewing operation that has stimulated coffeepot tinkerers to their most extravagant efforts: the separation of brewed coffee from spent grounds. Again, original ideas are few, refinements endless. People in many places in the world—the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Indonesia—have the most direct solution: They simply let most of the grounds settle to the bottom of the cup or pot and drink whatever remains along with the brew.

The original coffee drinkers, the Arabs of what is now Saudi Arabia and Yemen, apparently ground their beans coarsely and strained the coffee into the cup. Ethiopians and Eritreans still use simple strainers, often little wads of horsehair stuck into the narrow opening of the coffeepot.

Europeans Rediscover Strained Coffee. By the time Europeans discovered coffee via the Turks, the settling-to-the-bottom-of-the-cup approach to separating grounds and brew was near universal. Filtering was not reintroduced into the mainstream of coffee culture until 1684, after the lifting of the siege of Vienna, when Franz George Kolschitzky opened central Europe’s first café using coffee left behind by the routed Turks. Kolschitzky first tried to serve his booty Turkish style, but, according to legend, the Viennese resisted. They called it “stewed soot” and continued to drink white wine and lager with breakfast. But when Kolschitzky started straining the coffee and serving it with milk and honey, his success was assured. Within a few years the great café tradition of Vienna was well established. Strained or separated coffee has dominated European and American taste ever since.

The Ubiquitous Drip Method. A Frenchman named Jean-Baptiste de Belloy is credited with inventing the world’s favorite technology for separating coffee from grounds, the drip pot, in 1800. Hot water is poured into an upper compartment containing the coffee and is allowed to drip through a strainer or filter into a lower compartment, leaving the coffee grounds behind. An impressive variety of refinements has been developed since, including the Neapolitan flip pot, cloth filters, and disposable paper filters.

The Plunger Method. One other method of separation deserves mention. After the coffee is steeped, a metal filter or strainer is forced down through the coffee like a plunger, pressing the coffee grounds to the bottom of the pot and leaving the clarified coffee above. There is no accepted generic name for this sort of brewer. Some call it a plunger pot, others French press, after the country in which it first became popular.

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS FOR BREWING APPARATUS

Ideally, coffee brewers should be made of glass or porcelain. Stainless steel will do. If you have a choice in the matter, avoid aluminum. Food cooked in aluminum absorbs minute traces of the metal; coffee held in aluminum develops a metallic flatness. Add aluminum’s tendency to pit and corrode, and I think there is ample reason to avoid this metal in a coffee-maker. Tin plate may also faintly taint the flavor of coffee.

A pot should be easy to clean. Coffee is oily, and accumulated oil eventually contributes a stale taste to fresh coffee. Stubborn brown stains in the corners can be soaked out with a strong solution of baking soda or one of the commercial urn cleaners on the market. Glass and porcelain are the easiest to clean; aluminum and tin-coated metal the hardest. It is wise to avoid pots with seams or cracks, especially in the parts that come in direct contact with the brewed coffee. Check to make sure you can take the whole apparatus apart easily for an occasional thorough cleaning. In areas with alkaline, or hard, water, a lime deposit builds up even in the parts of the maker that are untouched by coffee. The universal remedy is a strong solution of vinegar. Run it through the works of the brewer, then rinse thoroughly.

BREWING INJUNCTIONS

Now for the inevitable list of brewing rules and precepts.

• Grind the coffee as fine as you can make it without losing any through the holes in the filter of the coffeemaker. Never grind it to a powder. French press and conventional (nonfilter) drip require a medium to coarse grind.

• Use plenty of coffee: at least 2 level tablespoons or 1 standard coffee measure per 5- to 6-ounce cup. You may want to use more, but I strongly suggest you never use less unless your coffeemaker explicitly instructs you to. Most mugs hold closer to 8 ounces than 6, so if you measure by the mug use 2½ to 3 level tablespoons for every mug of water. Coffee brewed strong tastes better, and you can enjoy the distinctive flavor in your favorite coffee more clearly. If you brew with hard water or if you drink your coffee with milk, you should be especially careful to brew strong. If you feel that you are sensitive to caffeine, adjust the caffeine content of your coffee by adding some caffeine-free beans.

• Keep the coffeemaker clean and rinse it with hot water before you brew.

• Use fresh water, as free of impurities and alkalines as possible.

• Brew with hot water, as opposed to lukewarm or boiling water (Middle Eastern and cold-water coffees are exceptions). A temperature of 200°F is ideal, which means bringing the water to a boil and then waiting a minute or two before brewing. If you have done everything else right and you are in a rush, however, water that has just stopped boiling will not seriously damage a good, freshly ground coffee.

• In filter and drip systems, avoid brewing less than the brewer’s full capacity whenever you can. If the pot is made to brew six cups, the coffee will taste better if you brew the full six.

• Some don’ts: Do not boil coffee; it cooks off all the delicate flavoring essence and leaves the bitter chemicals. Do not percolate or reheat coffee; it has the same effect as boiling, only less so. Do not hold coffee on heat for more than a few minutes for the same reason. Do not mix old coffee with new, which is like using rotten wood to prop up a new building.

Water Quality and Coffee Quality

Ninety-nine percent of a cup of coffee is water, and if you use bad, really bad, water, you might just as well throw away this book and buy a jar of instant. If the water is not pleasant to drink, do not make coffee with it. Use bottled water or a filter system. Hard, or alkaline, water does not directly harm flavor and aroma but does mute some of the natural acids in coffee and produces a blander cup with less dry brightness. Water that has been treated with softeners makes even worse coffee, however, so if you do live in an area with hard water, you might compensate by buying more acidy coffees (African, Arabian, and the best Central American origins) or by brewing with bottled or filtered water. Some automatic, drip coffeemakers come equipped with built-in filters. Although these integral filters are effective, they seem fussy and overspecialized to me. It might be better to buy a filtration system that can be used for all of your water needs, rather than one that is irrecovably stuck inside the coffee brewer.

BREWING METHODS AND MACHINERY

About 70 percent of the coffee consumed in the United States is brewed with paper filters, a method that produces coffee in the classic American style: clear, light-bodied, with little sediment or oil. Any other brewing method (except cold-water concentrate) produces a coffee richer in oils and sediments and heavier in flavor than the typical American cup of filter coffee. Those adventurers who experiment with other brewing methods should keep this difference in mind.

Open-Pot Brewing

The simplest brewing method is as good as any. You place the ground coffee in a pot of hot (just short of boiling) water, stir to break up lumps and saturate the coffee, strain or otherwise separate the grounds from the brewed coffee, and serve. Open-pot coffee is a favorite of individualists and light travelers. I had a sculptor friend who insisted on making his coffee in a pot improvised from a coffee can and a coat hanger. For such nonconformists, the challenge is separating the grounds from the coffee without stooping to the aid of decadent bourgeois inventions like strainers.

Bring the cold water to a boil and let it cool for a minute or so. Toss in the coffee. Use a moderately fine grind, about what stores call drip. Stir gently to break up the lumps and let the mixture steep, covered, for 2 to 4 minutes. If you are willing to compromise, obtain a very-fine-mesh strainer; the best are made of nylon cloth. Strain the coffee and serve. If you consider yourself too authentic for a strainer, pour a couple of spoons of cold water over the surface of the coffee to sink whatever grounds have not already settled. In theory, at least, the cold water, which is heavier than the hot, will carry these stubbornly buoyant pieces to the bottom.

For the lazy or less committed, some specialty stores sell a little nylon bag (about $5) that sits inside the traditional, straight-sided coffeepot, supported on the outside by a plastic ring. This simple device is a modern version of the Biggin pot, a device named after its early nineteenth-century English inventor. The Biggin pot was popular in England in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It has the added advantage of permitting a much finer grind of coffee than traditional open-pot methods. You put the ground coffee in the nylon bag, pour hot water over it, and stir lightly to break up the lumps. In 2 to 4 minutes, you simply lift the bag and grounds out of the brewed coffee.

French press or plunger brewer.

French Press or Plunger Brewing

French press is essentially open-pot coffee with a sophisticated method for separating the grounds from the brew. The pot is a narrow glass or metal cylinder. A fine-mesh-screen plunger fits tightly inside the cylinder. You put coarse-to-medium-ground coffee in the cylinder, pour water just short of boiling over it, and insert the plunger in the top of the cylinder without pushing it down. After about 4 minutes, when the coffee is thoroughly steeped, you push the plunger through the coffee, clarifying it and forcing the grounds to the bottom of the pot.

The plunger pot was apparently developed in Italy during the 1930s, but found its true home in France after World War II, when it surged to prominence as a favored home-brewing method.

The growing popularity of this method in the United States has unleashed a flood of French-press brewers, most of them manufactured everywhere except France. A consumer’s first decision in purchasing such a brewer is whether to spend a little money on a version that supports the glass, brewing receptacle in a plastic frame ($15 to $30), or to spend considerably more on a brewer with a metal frame ($40 to the totally unreasonable). A third alternative, and a good one, are designs that insulate the brewing receptacle to keep the coffee hot after brewing.

Complicating the decision is the enthusiasm with which the design community has embraced the French press. Its technical simplicity and potential as an after-dinner conversation piece has provoked an orgy of visual invention almost equaling the similar attention lavished on the designer teapot. Designer French presses range from inexpensive, urban-chic, plastic-framed units to understated, metal-sheathed designs that murmur money.

The plunger pot is an enthusiast’s brewer. It appeals to those who like to dramatize their coffee making. With the plunger brewer, coffee is not an after-dinner option that emerges routinely from the kitchen. It is the product of a small but satisfying ceremonial event that unfolds at the table.

The coffee the plunger brewer produces is heavy and densely flavored. The subtle, aromatic notes present in fresh, well-made filter coffee are overwhelmed by a deep, gritty punch. Many coffee drinkers prefer such coffee; others may find it muddy and flat-tasting. Those who take their coffee with milk or cream may prefer it; those who drink their coffee black may not. Some may like it after dinner but not before. It is neither better nor worse than coffee made with filter paper, just different. Its heavyish flavor and dense body are owing to the presence of sediment, oils, and minute gelatinous material that chemists call colloids, all of which are largely eliminated by paper filters.

Style of coffee aside, the advantages of the plunger brewer are its drama, its portability, and its elegance, all of which make it an ideal after-dinner brewer. It is more difficult to clean than most drip or filter pots, and, unless you buy a design with an insulated decanter, the coffee must be drunk immediately, which is just as well, since coffee ought to be drunk immediately.

Another virtue of the plunger pot emerged with the development of the travel press, a one-serving French-press brewer the size of a tall travel mug. A good version is distributed by Bodum. With this commuter-friendly device, it is possible to pour the hot water over the coffee on your way out the door, depress the plunger in the car while waiting for the first traffic light, and drink the fresh coffee directly out of the mug/pot while you maneuver down the freeway.

When you brew with your plunger pot, take care to preheat it with hot water, and take care to use a medium-to-coarse grind. With a fine grind the plunger will become almost impossible to push down. Also be careful to press the plunger straight down. If you try to push from an angle, you are likely to break the glass decanter.

Drip Brewing Without Filters

Invented by a Frenchman, the drip pot was popularized by Benjamin Thompson, an eccentric American who became Count von Rumford of the Holy Roman Empire, married two rich widows, and spent much of his leisure time making enemies and coffee. The drip maker typically consists of two compartments, an upper and a lower, divided by a metal or ceramic filter or strainer. The ground coffee is placed in the upper compartment and hot water is poured over it. The brewed coffee trickles through the strainer into the lower compartment.

The traditional American, straight-sided, metal drip pot has gone out of fashion, but an attractive, French-silhouette, porcelain version can be bought through some specialty stores and catalogs.

Gold-plated mesh filter units that turn any appropriately sized receptacle into a drip brewer are available for about $10 to $20, depending on size. Some can be purchased with a matching insulated serving carafe. You drip the coffee through the gold mesh filter into the carafe. From a technical point of view, such filter-insulated carafe sets are superior to the traditional drip pot, since keeping the coffee hot during brewing is one of the challenges of drip brewing. Make sure you preheat the carafe, however.

Use a medium grind of coffee in a drip brewer. If the coffee drips through painfully slowly or not at all, or if you find more sediment in your cup than you prefer, try a coarser grind. Even with the correct grind, you may find that you occasionally need to tap or jostle the pot to keep the coffee dripping. When you pour the hot water over the ground coffee, make certain that you mix it lightly to saturate all of the coffee. Cover to preserve heat. Mix the coffee lightly again after it has brewed, since the first coffee to drip through is stronger and heavier than the last.

Traditional ceramic drip brewer.

Both drip and filter coffees often cool excessively during the brewing process. If you are not brewing into an insulated carafe, preheat the bottom half of the pot with hot tap water before brewing. If that is not enough, buy a heat-diffusing pad and keep the pot on the stove while brewing.

Flip-Drip or Neapolitan

Macchinetta Brewing

A popular variation of the drip pot was invented in 1819 by Morize, a French tinsmith. This is the reversible, double, or flip-drip pot, which has since been adopted by the Italians as the Neapolitan macchinetta. Rather than being laid loosely on top of the strainer, as in the regular drip pot, the ground coffee is secured in a two-sided strainer at the waist of the pot. The water is heated in one part of the pot, then the whole thing is flipped over, and the hot water drips through the coffee into the other, empty (and nicely warm) side. These devices make excellent drip-style coffee.

Several versions of the flip-drip pot are manufactured, but can be difficult to turn up. See Sending for It. An aluminum version is the cheapest (around $10). Since aluminum is an undesirable material for coffee brewers, I recommend instead a traditional-look copper version (around $40) or a contemporary-look stainless ($40 and up).

Pumping Percolator Brewing

Until about thirty years ago, the pop of a pumping percolator–producing coffee ranked with the acceleration of a well-tuned car as one of North America’s best-loved sounds. Now the pumping percolator has gone the way of tail fins and bologna sandwiches. However reassuring the sensuous gurgle of a percolator is psychologically, chemically it means only one thing: the percolator is boiling the coffee and prematurely vaporizing the delicate flavoring oils. Every pop of the percolator means another bubble of aroma and flavor is bursting at the top of the pot, bestowing its gift on your kitchen rather than on your palate.

Opinions differ as to the extent of the damage that the percolator inflicts on coffee flavor. In 1974, when the pumping percolator was still holding off the automatic, filter-drip brewer, Consumer Reports served coded cups of drip and percolator coffee both to experts and to its staff. The experts unanimously and consistently preferred the drip coffee to the perked coffee, but the staff’s reaction was mixed. I find I can invariably pick out perked coffee in a similar test by the slightness of its aroma and the flat, slightly bitter edge of its flavor. However, there are more ways to ruin coffee than to put it in a good pumping percolator; stale coffee, for instance, tastes bad no matter how you brew it. Freshly opened canned coffee brewed with care in a good pumping percolator tastes better than mishandled, three-month-old Jamaica Blue Mountain put through a filter.

If you must have a pumping percolator, a good electric is probably the best choice, since the heat is automatically controlled to produce perked rather than boiled coffee, and most electrics incorporate a thermostat intended to reduce the heat at the optimum moment to prevent overextraction.

Recall that in the vaccum filter method heat forces water from one sealed chamber into a second, where it mixes with the ground coffee. The vacuum created by the departure of the water from the first chamber then draws the now-brewed coffee back through a filter into the chamber. Because the manipulations involved in the vacuum brewing are a bit more complex than those demanded by the filter method, the vacuum pot has lost considerable popularity since its heyday in the 1920s and 1930s. But, for some, the leisurely and alchemical shifting of liquids in the two chambers has a continuing appeal.

Cultures that value ceremony are particularly fond of the vacuum filter. In Japan, for example, one-cup vacuum brewers are widely used in coffeehouses to custom-brew specialty “call” coffees. The heat is provided either by torchlike gas flames that shoot dramatically straight out of metal counters or by halogen lamps that cast a mesmerizing glow up through the brewing coffee.

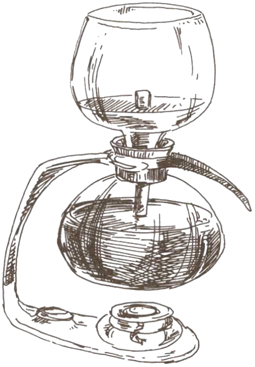

Vacuum brewer.

Furthermore, coffee brewed by the vacuum method often tastes fuller and richer than coffee brewed through paper filters, while remaining free of the grit that often mars the taste of French-press-brewed coffee. Perhaps for this reason, the vacuum pot is undergoing a bit of a renaissance among specialty coffee insiders.

Unfortunately, that renewal of interest is only marginally reflected in the range of vacuum pots currently available in the retail marketplace. As I write, the only vacuum brewers generally available in the United States are the simple, attractive, but rather flimsy six-cup Bodum (around $30) and large, relatively expensive ($170) Starbucks Barista Utopia. The Starbucks device represents a freshly imagined and engineered version of the vacuum brewer, with a programmable heat source that automates the brewing procedure and turns the fussy old vacuum pot into a contemporary automated program-it-and-forget-it machine. Unfortunately, this admirably intentioned effort may be too expensive to succeed in the contemporary marketplace. I hope that by the time you read these pages, someone will have supplied the market with the inexpensive, streamlined version of the vacuum pot that will succed in reviving this effective and charming brewing method.

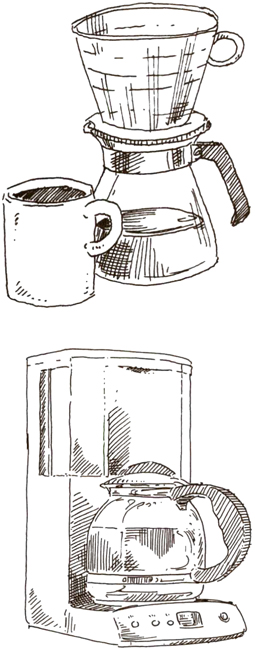

Top, manual, pour-over, filter-drip cone and decanter. Bottom, automatic, filter-drip brewer.

FILTER-DRIP BREWING, AUTOMATIC AND OTHERWISE

Coffeepot tinkerers started using cloth filters around 1800; disposable paper filters came later and were never really popular until after World War II. The main objection to paper filters then and now is that they must continually be replaced. The main objection to cloth filters is that they get dirty and are difficult to clean. In this age of disposables, the paper filter has triumphed, but permanent filters, in nylon mesh or gold-plated metal, are currently making inroads. The use of permanent metal filters blurs the distinction between ordinary drip brewing and filter brewing since they essentially turn a filter-drip brewer into a nonfilter-drip brewer. The description and admonitions that follow refer to coffee brewed with paper filters, not with metal or nylon mesh filters.

Filter coffeemakers come in two basic versions: inexpensive (or nostalgic) manual designs in which you pour the water over the ground coffee yourself, and the ubiquitous automatic, filter-drip machines, which do the water pouring for you. Both fundamentally work the same way. A paper filter is placed in a plastic, glass, or ceramic holder; fine-ground coffee goes in the filter, and hot water, poured by you or the machine, goes into the filter. The coffee exits the filter into a carafe.

The advantages of filter brewing: It permits you to use a very fine grind of coffee and effect a quick, thorough extraction. The paper filters make the grounds easy to dispose of and the coffeemaker easy to keep clean. Because of their simplicity and popularity, both pour-over, manual filter devices and their automatic brethren are among the cheapest coffee-brewing devices on the market. Those who like a light-bodied, clear coffee free of oils, colloids, and sediment will enjoy a good filter coffee; those who like a heavier, richer brew will prefer other methods.

A Note on Filter Papers

Virtually all white filter papers manufactured today are whitened without use of dioxin, a carcinogen that was used in bleaching paper through the late 1980s. For this reason, I feel confident in recommending white filter papers in preference to brown, which impart a cardboardy taste to the brewing water and which may harbor some dubious chemicals of their own, including tars.

Permanent, Nonpaper Filters

A note on permanent filters: I do not recommend cloth filters, since they are difficult to keep clean. Gold-plated permanent filters, in both standard Melitta wedge and basket styles, are excellent products, but, if you like filter coffee, you may not like coffee made with these filters as much as you like coffee brewed with paper filters. The mesh allows a good deal of sediment and colloids to enter the brewed coffee, which gives it a heavy, often gritty taste, closer in style to French-press coffee. Permanent filters also require a coarser and more uniform grind to work correctly.

Manual, Pour-Over Filter Brewing

Fewer and fewer people choose to pour the water over the coffee themselves when automatic, filter-drip brewers sell for as little as $15 or $20. Reasons to pour yourself: The basic plastic cone-and-glass decanter set is still the cheapest brewing device on the market, short of a tin can and coat hanger; pour-over units do not require counter space, you can be absolutely sure all the ground coffee is saturated because you are doing the pouring yourself; and you can congratulate yourself on being a coffee purist.

Most important, however, you can stir the water and grounds in the cone as they steep. This last possibility is of great importance to some aficionados. I live in an area dominated by the cult of Peet’s Coffee, and friends often ask me why, when they get their pound of Major Dickason’s Blend home, they cannot get it to taste like the extraordinarily deep-bodied but clear-tasting drip coffee they drink at Peet’s stores. For two reasons, I tell them. First, they need to brew extremely strong (about 3 tablespoons of ground coffee to every 5- or 6-ounce cup); and second, they need to stir the grounds as they steep, an impossible action with automatic, filter-drip brewers. So if you do prefer a coffee almost as full-bodied as French press but without the French-press grit, you may need to experiment with a manual, pour-over brewer. After you saturate the grounds, stir them with a long-handled spoon until most of the coffee has exited the filter.

The disadvantages to manual, pour-over, filter-drip brewers? In addition to the obvious inconvenience of heating and pouring the water yourself, it is also very difficult to keep the coffee hot. You need to either preheat the decanter and drink the coffee immediately, keep the decanter atop an electric warmer or other heating device, or brew directly into a preheated, insulated decanter, probably the best approach.

At the most democratic end of the price-design spectrum for manual, pour-over brewers are simple plastic filter holders, sold either with matching decanter or without. More costly and more idiosyncratic are various models of the nostalgic, defiantly impractical Chemex, the ancestor of all American filter-drip brewers. The Chemex was developed from, and still resembles, a well-made piece of laboratory equipment. Many find its austere design (honored by the Museum of Modern Art in New York) and authentic materials (glass and wood in the traditional models) attractive, but the single-piece hourglass shape makes cleaning difficult. Another classic option is a matching porcelain cone and decanter from Melitta with classic, rounded lines reminiscent of traditional French-drip pots. Fante’s in Philadelphia (see Sending for It) is a good last-resort source for exotic filter-drip models like both the Chemex and the Melitta porcelain design.

Suggestions for Manual, Pour-Over Filter Brewing. Careful brewing can make a considerable difference in the quality of filter coffee. Bring cold water to just short of boiling and pour a little over the grounds, making sure to wet all the coffee. Pour the rest of the water through. If you want a particularly strong, rich cup, stir the water and grounds as they steep and drip. Stir the coffee in the decanter lightly after brewing. If you make a small quantity, less than four cups, use slightly more ground coffee to compensate for the flavor lost to the filter, and wet the filter before you put in the ground coffee. Always preheat decanter and cups by rinsing them in hot water. If possible, brew into a preheated, insulated carafe.

Automatic, Filter-Drip Brewing

Convenience and a clear, transparent cup seem to have driven the success of the automatic, filter-drip brewer, which in the years since its introduction in the early 1970s has become America’s favorite brewing device. The heart of the system is the familiar paper filter, filter holder, and decanter. The machine simply heats water to the optimum temperature for coffee brewing and automatically releases it into the ground coffee in the filter. The brewed coffee drips into the decanter, while an element under the decanter keeps the coffee hot once it is brewed. You measure cold water into the top of the maker, measure coffee into the filter, press a switch, and, in from 4 to 8 minutes, obtain 2 to 12 cups of coffee.

Furthermore, the manufacturers of these brewers have considerably improved their performance over the past fifteen years. Most of the leading makers have resolved such problems as ground coffee floating or forming a doughnut around the edge of the filter basket, variations in water temperature, and excessively slow or fast filtering.

Some years ago I was certain that I could make better filter coffee than any of these machines could simply by pouring the water over the coffee myself by hand. Now I am not so sure. Even the cheapest, mass-marketed machines have improved, with most of the egregious performers of yesteryear eliminated from the shelves. A rather rigorous 1999 test in which I took part turned up no bad performers whatsoever among the models tested. Furthermore, the low-end, mass-marketed brewers performed almost as well as a selection of more expensive, high-end models. It appears that the main criteria for choice in these brewers are appearance, the prestige of the manufacturer’s name, and, above all, an impressive and often baffling array of special features.

Automatic, Filter-Drip Special Features. Following is a list of special features that attempt to lure buyers to spend more than $15 or $20 on a basic automatic, filter-drip coffee brewer. Some features are very useful; others seem like marginal marketing gimmicks.

• A pause feature enables you to temporarily interrupt the brewing cycle to pour a cup of coffee. This is a very useful feature, given that coffee drinkers are not known for their patience.

• An under-the-cabinet design saves space by allowing you to mount the machine beneath a kitchen cabinet, suspended over the counter. Obviously, only you can decide on the usefulness of this feature.

• A thermos carafe, designed to keep the coffee hot without the usual warming plate, is extremely helpful for those who want to hold coffee for any length of time. The sealed thermos retains flavor and some aroma, both of which deteriorate rapidly when the coffee is subjected to an external heat source such as a hot plate. Of course, the absolutely best solution is to buy a smaller-capacity brewer and brew more frequently.

• A closed system, designed to retain heat and aroma during the brewing process, accounts for the reticent look of many brewers. If all else is equal, a closed system undoubtedly improves flavor and aroma. However, if you let coffee sit on the hot plate of the brewer for longer than 3 to 4 minutes before you drink it, a feature like this is rendered utterly irrelevant.

• Timing devices enable you to set the brewer to wake up with freshly brewed coffee. The night before, you fill the water and coffee receptacles and set the timer. The disadvantage is that the ground coffee stales all night long. Still, I would not hold it against any coffee lover who bought one. The most exotic designs attempt to eliminate staling by incorporating a grinder into the brewer; at the appointed time these devices not only brew coffee but grind it as well. All of the grinder-brewer combinations that I have tried have proven to be technically flawed, but someone may get it right.

• Permanent filters of nylon or metal mesh. If you like the clarity and brightness of filtered coffee, you do not want this feature. Avoid buying a maker that permits you to use only the permanent filter and does not give you the option of using paper.

• The coffee-strength controls on some brewers seem to be of dubious value. With some, the strong setting may even cause the coffee to be overbrewed and harsh. If you want stronger brewed coffee, simply use more ground coffee.

• A provision for brewing a smaller amount of coffee on some machines appears to mildly improve brewing quality for small batches.

• Built-in water filters have cartridges that must be replaced periodically. They correct for both impurities and extremely hard water. I give the manufacturers who feature these filters a high grade for effort but suggest that if your water is bad you may have a general problem that transcends coffee brewing and needs to be resolved with either bottled water or a filtration system.

• Various technical strategies for ensuring that all of the ground coffee is thoroughly saturated and involved in the infusion process are often touted in promotional materials. I am not certain that these strategies should be called features because all automatic filter brewers aim for thorough infusion of the coffee through one technical means or another. Publicists carry on about sprinklers, pulses, surges, and gushes. Soon I expect built-in leprechauns with spoons. The objective is to agitate the coffee, break up lumps or doughnuts of dry coffee, and ensure a thorough infusion. At this writing the only brewer with a genuinely different approach to the infusion-saturation process is the Amway Kahve Coffee Maker, which gently spins the filter basket, forcing water through the ground coffee with centrifugal action and, in effect, wringing the coffee out like washing machines wring out clothes.

• Hot plates that turn off automatically to prevent fires and fouled carafes could be extremely useful to coffee drinkers with bad memories.

• Various means have been developed to modulate the temperature of the warming plate so as to keep coffee hot with less loss of flavor. The loss of flavor through holding coffee on the warming plate is one of the great drawbacks to automatic filter machines. The best solution is to brew smaller amounts of coffee more frequently; the second best approach is to buy a machine that brews directly into an insulated carafe. Anything else, no matter how innovative, is simply another desperate expedient.

Filter Brewers with Built-in Grinders

Now and then, manufacturers bring out automatic brewers with built-in, coffee-grinding apparatus. The idea sounds like a splendid one for the time-crunched, morning-challenged gourmet: you load with whole-bean coffee the night before, set a timer, and wake up to the sound and aroma of coffee being both ground and brewed for you by your countertop robot.

So far, however, none of these attempts has met with much market success. With the earliest designs, the grinding and brewing took place in the same receptacle. After a pair of blades knocked the coffee to pieces, hot water bubbled directly over it and the brewed coffee dripped through a mesh filter into the decanter below.

These devices produced a rather heavy, silty cup for two reasons. First, the position of the grinder blades in the middle of the brewing compartment prevented the use of paper filters. Second, blade grinders tend to produce a dusty, uneven grind when they are not manipulated to keep the coffee circulated around the blades.

At least one later design attempted to solve the silt problem by separating the grinding and brewing processes into adjacent compartments, making it possible to use paper filters. But technical problems combined with high prices have prevented these later efforts from achieving success as well.

If any of these innovative designs could improve quality and reduce price, they might find a market in the United States. As it is, I suspect that their appeal will continue to be limited to gadget enthusiasts looking for bragging rights.

BREWING FOR ONE OR TWO

With the exception of espresso, most brewing systems produce their best coffee in larger-than-one-cup quantities. The flavor loss is particularly acute with filter coffee, since in a one-cup brewer the paper filter overpowers the coffee. So, if you prefer filtered coffee and are looking for quality, you might consider buying a two- to four-cup brewer and brewing a bit more than you need. I use a four-cup, automatic, filter-drip brewer charged with about three (5-ounce) cups of water and three heaping measures of coffee. That formula nets a tall mug of strong, hearty coffee.

If you use a one-cup, manual, pour-over filter-drip cone, make certain you preheat the cone and cup before you brew. It also helps to wet the filter paper at the same time that you preheat the cone, to mute the impact of the filter on the coffee. The little electric cup warmers sold as desktop accessories are useful for keeping your cup hot while you brew.

If you enjoy denser, punchier coffee of the kind made without a paper filter, you have more options. One-cup, gold-plated metal mesh filters (around $10 to $15) make a good cup, providing you use a bit more ground coffee than usual and preheat the filter and cup.

Two-cup plunger or French-press brewers also make excellent coffee in the heavier style. You can get a plastic-framed version for as little as $12. Perhaps the best solution for coffee drinkers on the run is the travel press (distributed by Bodum), a one-serving press-pot that doubles as a travel mug. It allows you to press the coffee and drink it out of the same mug-sized receptacle.

CONCENTRATE BREWING

In Latin America, as well as in many other parts of the world, a very strong, concentrated coffee is brewed, stored, and added in small amounts to hot water or milk to make a sort of preindustrial-age instant coffee. It is very easy to make your own concentrate, but pre-made liquid concentrates are beginning to appear in supermarkets and fancy food stores. The most authentic of those I have seen, Victorian House Concentrated Coffee, is a genuine, natural concentrate produced from good coffee with no additives, but like all concentrates, it produces a light-bodied cup with little aroma. And priced by the cup, it is not cheap.

You can obtain a strong concentrate with almost any brewing method, although only one, the cold-water method, has gained much popularity in the United States.

Hot-Water Concentrate Brewing

To make a hot-water concentrate, use 8 cups of water to 1 pound of finely ground coffee and brew in your customary fashion. If the coffeemaker is unable to handle a pound at a time, halve the recipe or brew twice. Store the resulting concentrate in a stoppered bottle in the refrigerator. To a preheated cup, add about 1 ounce for every 5 ounces of hot water. A bartender’s shot glass makes a convenient measure.

Cold-Water Concentrate Brewing

The cold-water concentrate method has been adopted by the Toddy coffeemaker (around $30). You steep 1 pound of regular-grind coffee in 8 cups of cold water for 10 to 20 hours, filter the resulting concentrate into a separate container, store it in the refrigerator, and add it to hot water in proportions of 1 ounce to 1 cup.

The result is a very mild, delicate brew, with little acidity (of either the good or bad variety), light body, a natural sweetness, and an evanescent, muted flavor. Those who take coffee weak and black and who like a delicate flavor free of acidy highlights and complex idiosyncrasies may well like the cold-water method. Those who for medical reasons require a milder brew also might find it suitable. And it is convenient.

However, anyone who likes strong coffee, distinctive coffee, or coffee with milk would be better off brewing another way. Another problem: If you combine 1 or more ounces of refrigerated concentrate with 5 ounces of hot water, you produce a mixture considerably less than scalding hot. Add milk and your cup will be lukewarm.

Some people like to use cold-water concentrate in cooking, but I prefer hot-water concentrate because the coffee flavor is stronger and more distinctive. Cold-water concentrate makes everything taste like commercial coffee ice cream. The same can be said for using cold-water concentrate in cold coffee drinks: It is true you need a concentrate to compensate for dilution by ice, but some (like me) prefer the more distinctive punch of hot-brewed concentrate.

Improvised Cold-Water Brewing. You do not have to buy a cold-water brewer to enjoy cold-water coffee, although the Toddy device is more convenient than any expedient. To improvise, you need a glass bowl, a large coffee cone, filters to fit, and a bottle with an airtight (not a snap-on plastic) closure in which to refrigerate the finished concentrate. Take 1 pound of your favorite coffee, regular grind. You can use any coffee, any roast. Put it in the bowl, and add 8 cups of cold water. Poke the floating coffee down into the water so all the grounds are wet, then let the bowl stand in a cool, dark place for 10 to 20 hours, depending on how strong you want the concentrate. When the brewing period is over, use the cone to filter the concentrate into the second, airtight container and store in the refrigerator. For hot coffee, use 1 to 2 ounces per cup.

Concentrate keeps its flavor for months if the bottle is tightly capped, but it is best to make only as much as you will drink in a week or two. Some people freeze the concentrate, but I have found it loses some much-needed flavor, and I suggest you simply halve the recipe if you cannot drink 8 cups of concentrate in two weeks.

MIDDLE EASTERN OR TURKISH BREWING

Middle Eastern coffee is most often called Turkish coffee in this country, but this is a misnomer. For one thing, it is drunk all over the Middle East, the Balkans and Hungary, not only in Turkey. Second, according to all accounts, the method was invented in Cairo and later spread from there to Turkey. Middle Eastern coffee is unique, first, because some of the coffee grounds are deliberately drunk along with the coffee, and second, because the coffee is usually brewed with sugar, rather than sweetened after brewing. Much of the coffee settles to the bottom of the cup, but some tiny grains of coffee are suspended in the sweetened liquid, imparting a heavy, almost syrupy weight to the beverage.

Equipment and Coffee for Middle Eastern Brewing

It is possible to produce good, flavorful Middle Eastern–style coffee in any pot. The investment you make in brewing equipment is more important to ritual and esthetics than to flavor. Nevertheless, ritual seems to be as significant as flavor is in the enjoyment of coffee, and you may want to be authentic. If so, you will need a small, conical pot that looks a little like an inverted megaphone, called an ibrik (Turkish) or briki (Greek). The best and most authentic are made of copper or brass, are tinned inside, and cost about $20. You should also have either demitasse cups and saucers or tiny cups with metal holders especially made to serve Middle Eastern coffee. The best place to buy such gear is in stores in Middle Eastern neighborhoods, the kind that sell spices and other foods.

The most important piece of functional equipment in making Middle Eastern–style coffee is the grinder. Since you in part drink some of the grounds along with the coffee, you do not want to be picking grains of coffee from between your teeth. Consequently you need a very fine, uniform grind, a dusty powder in fact. Few home mills can produce such a grind. The Zassenhaus box mills described in Chapter 8 do a decent job. Countries that take this kind of coffee drinking seriously produce attractive brass hand mills especially for this brewing method. If you purchase this style of grinder, I suggest that you buy the largest and sturdiest one you can find. The cheaper ones appear to be more tourist trinkets than true grinders. Fante’s in Philadelphia (see Sending for It) carries a good selection. The only electric machines that I know for certain produce a consistently good Middle Eastern–style coffee are specialized, home espresso grinders produced by companies like Saeco and Rancilio.

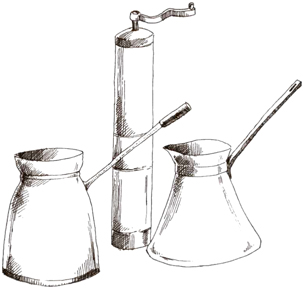

Middle Eastern– or “Turkish”-style coffee implements. Left and right, ibriks. Center, grinder.

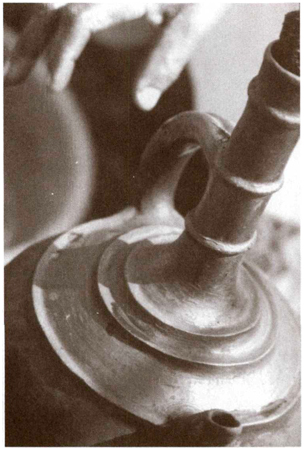

Clay pot of the kind used in Ethiopia and Eritrea to brew coffee.

Most store grinders kept in proper adjustment will produce a superfine grind appropriate for Middle Eastern brewing. The joker is the adjustment. Many supermarket grinders are perpetually out of adjustment. Try the “Turkish” setting and see whether the coffee that spews out is ground literally to a powder. If it is not—in other words, if what comes out is a fine grit rather than a powder—try another store and another grinder.

The coffee roast you choose is a matter of taste, as is the provenance of the coffee. Most “Turkish”- or Middle Eastern–style coffee sold in the United States is a fairly dark roast, the sort most stores sell as Italian. The finest and most authentic Middle Eastern coffee is a Yemen Mocha or good Ethiopia Harrar brought to a dark brown roast. A blend of any winy coffee, such as Kenya or Yemen Mocha, some Sumatra, and a good dark French roast also makes an excellent Middle Eastern coffee.

Brewing Technique for Middle Eastern Coffee

Authentic Middle Eastern coffee should have a thin head of brown froth completely covering the surface of the coffee. In Greece, this is called the kaimaki, and to serve coffee without it is an insult to the guest and a disgrace to the host. A Greek friend of mine tells about her mother secretly struggling in the kitchen to produce a good head of kaimaki, while the rest of the family nervously diverted the guests with small talk in the parlor. In the United States the kaimaki may be dispensed with for the simple reason that it is very difficult to produce. The Middle Eastern coffee that you make should taste good the first time you make it, and the froth can wait until you are an expert.

Never plan to fill the ibrik to more than one-half its capacity. You need the other half to accommodate the froth that boils up from the coffee. Start by measuring 2 level-to-rounded teaspoons of freshly ground coffee per demitasse into the ibrik. Add about 1 level teaspoon of sugar for every teaspoon of coffee. This makes a coffee a Greek would call sweet. Add 1½ teaspoons of sugar per 1 teaspoon of coffee and you get heavy sweet; ½ teaspoon is light sweet. Omit sugar and you are serving the coffee plain, or sketo.

Now measure the water into the ibrik. Stir to dissolve the sugar, then turn on the heat medium to high. After a while the coffee will begin to boil gently. Let it boil, but watch it closely. Eventually the froth, which should have a darkish crust on top, starts to climb the narrow part of the ibrik. When it fills the flare at the top of the pot and is at the point of boiling over, turn off the flame. Immediately and carefully, to avoid settling the froth, pour the coffee into the cups. Fill each cup halfway first, then return to add some froth. Again, even though you may fail with the froth, the coffee is always delicious.

Middle Easterners like to add spices to their coffee. The preferred spice, and the one I suggest you try, is cardamom. Grind the cardamom seeds as finely as you grind the coffee and add them to the water with the coffee and sugar. There are usually three seeds in a cardamom pod; start by using the equivalent of one seed (not pod) per demitasse of water, or a pinch if the cardamom is preground.

SOLUBLE OR INSTANT COFFEE

Making instant coffee is hardly brewing, but I do not have a chapter on mixing and stirring, so I will have to include my discussion of instant or soluble coffees here as an exemplary afterthought.

I would not insinuate that soluble-coffee producers are terrible people who sneak around in dark clothing and limousines, stealing the public’s right to a rich, fragrant cup of real coffee. Instant-coffee technologists seem passionately involved in their quest for a better coffee. At first glance (not taste), instant coffee does seem to offer many advantages: It stays fresh longer than ordinary roasted coffee; it eliminates the mistakes that can occur when brewing ordinary roasted coffee; it can be made quickly; it can be mixed by the cup to individual taste; and it contains somewhat less caffeine than regularly brewed coffee. Furthermore, because the process of producing instant coffee neutralizes strong or unusual flavors, the manufacturer can use cheaper beans and pass the savings on to the consumer.

Dismissing Advantages

Yet few of instant coffee’s apparent advantages prove out. Instant does stay fresher, but grinding your own makes an even fresher cup. Instant is cleaner, but so are frozen dinners. True, it is hard to ruin a cup of instant, but if you have read this far, you are an expert anyhow. And if it is convenience you are looking for, the one-cup drip or plunger pot will give you much better coffee and just as quickly. So I cannot see any reasons except tidy countertops and a slight edge in price to recommend instant.

And you do not need instant coffee on backpacking or canoeing trips either. Open-pot coffee works fine in the wilds and adds no more weight than instant. At five in the morning, after brushing the earwigs out of your sleeping bag and cleaning up the mess the raccoons made, you need a cup of real coffee. About the only advantage to instant is that it does not attract bears.

Finally, for those who like to experiment with authentic and unusual coffees, the instant-coffee world offers no true alternatives. The “exotic,” instant-coffee mixes currently in the supermarkets are insipid fabrications. By comparison, freeze-dried Colombia is a far superior beverage. If you crave variety, you must go back to basics.

Once we dismiss the advantages of instant, the advantages of brewed-from-scratch stand out in fragrant relief. Why does instant often taste more like liquid taffy than coffee? The key, again, is the extremely volatile coffee essence, which provides the aroma and most of the flavor of fresh coffee. Remember that this oil is developed by roasting and remains sealed in little packets in the bean until liberated by grinding and brewing. Once the coffee essence hits the water, it does not last long, which is the reason coffee that sits for a while tastes so flat.

Putting the Flavor Back In

Instant coffee is brewed much the way a gourmet would brew coffee from beans at home: The beans are roasted, immediately ground, and brewed in gigantic percolators, filter urns really. But when that fresh, hot brew is dehydrated, what happens? Remember, to dehydrate means to remove the water, and with the water goes—yes, the coffee essence, the minute droplets of flavor and aroma that mean the difference between tasteless, bitter brown water and real coffee.

But here technology comes clattering over the hill to save the day. If the flavor is lost, well then, put it back in again. Coffee technologists have long known that much of the essential oil literally goes up in smoke and out the chimneys of their roasters. So—you guessed it. The instant-coffee people condense some of the essential oil lost in roasting and put it back in the coffee just before the coffee is packed. Clever? Also tricky—so much so that even according to industry admissions, the sharp corners of coffee flavor are neutralized. The instant process makes bad coffee beans taste better and good coffee beans taste bad.

Soluble Coffee and the Soul

So far in my attempts to discredit instant coffees I have stuck to concrete factors such as efficiency and price and fairly clear subjective factors such as flavor and aroma. But I must add that the ritual of making a true cup of coffee the right way every morning is good for the soul. It cuts down on heedless coffee-holism and helps to steady the heart for the more complex activities to come. It gets you started with the confidence that you can at least make a good cup of coffee, and it is always best to start out winning.

THE METHOD FOR YOU

Which brewing method is best? is a naïve question. Which brewing method is best for you is a question to which it is possible for you to approximate an answer. Take just two variables, body and convenience. Coffee made by the “Turkish” or Middle Eastern method is the heaviest in body, espresso the next heaviest, and cold-water coffee the lightest, with coffee brewed through paper filters a close second. Between them are the coffees produced by all the other methods: open pot, plunger pot, drip, and so on. Who is to say which is best?

Even the question of convenience is relative. The cold-water method is clearly the most convenient, automatic filter drip is a close second, and Middle Eastern and open pot are last. Still, no one could tell my sculptor friend that making coffee without a strainer in a coffee can is bad because it is clumsy and inconvenient. He appreciated the inconvenience; it added to his satisfaction and took his mind off the obscure anxieties of his work. One of the principal reasons for drinking coffee is the aesthetic satisfaction of ritual. You ought to love not only the coffee your pot makes but the pot itself and all the little things you do with it.