Learning Objectives

After Chapter 1.7, you will be able to:

- Identify whether an object is in equilibrium

- Calculate torque within a system:

After Chapter 1.7, you will be able to:

So far we’ve been paying attention to kinematics and the special cases of linear and projectile motion. However, many times the MCAT will require you to eliminate acceleration, or otherwise maintain a system in equilibrium. To accomplish this, you must be familiar with analyzing forces, especially with free body diagrams, as well as with the special conditions for translational and rotational equilibrium. The study of forces and torques is called dynamics.

While we all have an intuitive sense of forces (and their effects) in everyday life, students often struggle to represent them diagrammatically. Drawing free body diagrams takes some practice but will be a valuable tool on the MCAT. On Test Day, make sure to draw a free body diagram for any problem in which you must perform calculations on forces.

When dealing with dynamics questions, always draw a quick picture of what is happening in the problem; this will keep everything in its proper relative position and help prevent you from making simple mistakes.

Translational motion occurs when forces cause an object to move without any rotation. The simplest pathways may be linear, such as when a child slides down a snowy hill on a sled, or parabolic, as in the case of a cannonball shot out of a cannon. Any problem regarding translational motion in the Chemical and Physical Foundations of Biological Systems section can be solved using free body diagrams and Newton’s three laws.

Translational equilibrium exists only when the vector sum of all of the forces acting on an object is zero. This is called the first condition of equilibrium, and it is merely a reiteration of Newton’s first law. Remember that when the resultant force upon an object is zero, the object will not accelerate; that may mean that the object is stationary, but it could just as well mean that the object is moving with a constant nonzero velocity. Thus, an object experiencing translational equilibrium will have a constant velocity: both a constant speed (which could be zero or a nonzero value) and a constant direction.

If there is no acceleration, then there is no net force on the object. This means that any object with a constant velocity has no net force acting on it. However, just because the net force equals zero does not mean the velocity equals zero.

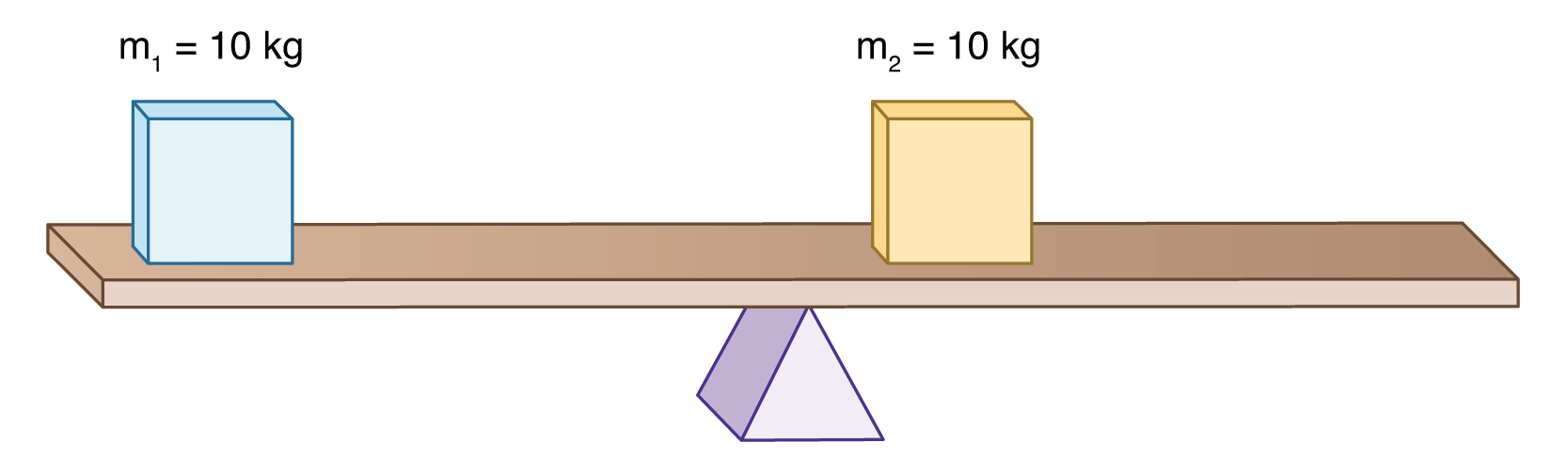

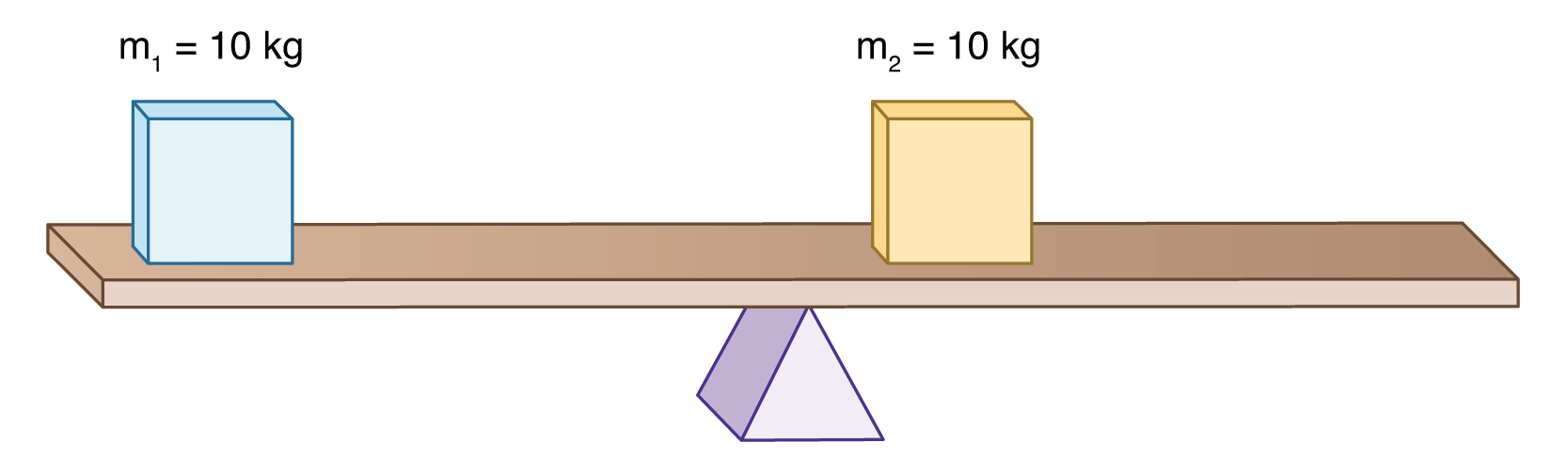

Rotational motion occurs when forces are applied against an object in such a way as to cause the object to rotate around a fixed pivot point, also known as the fulcrum. Application of force at some distance from the fulcrum generates torque (τ) or the moment of force. The distance between the applied force and the fulcrum is termed the lever arm. It is the torque that generates rotational motion, not the mere application of the force itself. This is because torque depends not only on the magnitude of the force but also on the length of the lever arm and the angle at which the force is applied. The equation for torque is a cross product:

where r is the length of the lever arm, F is the magnitude of the force, and θ is the angle between the lever arm and force vectors.

Remember that sin 90° = 1. This means that torque is greatest when the force applied is 90 degrees (perpendicular) to the lever arm. Knowing that sin 0° = 0 tells us that there is no torque when the force applied is parallel to the lever arm.

Rotational equilibrium exists only when the vector sum of all the torques acting on an object is zero. This is called the second condition of equilibrium. Torques that generate clockwise rotation are considered negative, while torques that generate counterclockwise rotation are positive. Thus, in rotational equilibrium, it must be that all of the positive torques exactly cancel out all of the negative torques. Similar to the behavior defined by translational equilibrium, there are two possibilities of motion in the case of rotational equilibrium.

Either the object is not rotating at all (that is, it is stationary), or it is rotating with a constant angular velocity. The MCAT almost always takes rotational equilibrium to mean that the object is not rotating at all.