Discrete Practice Answers

- C

The absolute and gauge pressures depend only on the density of the fluid, not on that of the object. When the pressure at the surface is equal to atmospheric pressure, the gauge pressure is given by Pgauge = ρgz, where ρ represents the density of the fluid, not the object. These objects are also at the same depth, so they must have the same gauge pressure. - B

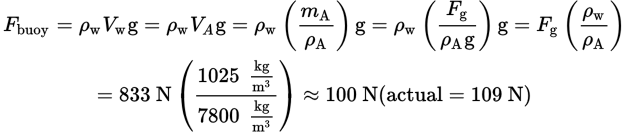

The tension in the chain is the difference between the anchor’s weight and the buoyant force because the object is in translational equilibrium: T = Fg – Fbuoy. The object’s weight is 833 N, and the buoyant force can be found using Archimedes’ principle. The magnitude of the buoyant force is equal to the weight of the seawater that the anchor displaces:

Fbuoy = ρwVwgBecause the anchor is submerged entirely, the volume of the water displaced is equal to the volume of the anchor, which is equal to its mass divided by its density

We are not given the anchor’s mass, but its value must be the magnitude of the weight of the anchor divided by g. Putting all of this together, we can obtain the buoyant force:

We are not given the anchor’s mass, but its value must be the magnitude of the weight of the anchor divided by g. Putting all of this together, we can obtain the buoyant force:

Lastly, we can obtain the tension from the initial equation T = Fg – Fbuoy:

T = 833 N − 109 N = 724 NThe key to quickly solving this problem on Test Day is recognizing that the answer choices contain an outlier (A), a value slightly less than the weight of the anchor (B), the weight of the anchor (C), and a value slightly higher than the weight of the anchor (D). Since buoyant force is in the same direction as tension and their sum must equal the weight of the anchor, (B) is the most likely answer.

- A

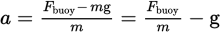

Using Newton’s second law, Fnet = ma, we obtain the following equation:

Fbuoy − mg = maThus,

Both balls experience the same buoyant force because they are in the same liquid and have the same volume (Fbuoy = ρVg). Thus, the ball with the smaller mass experiences the greater acceleration. Because both balls have the same volume, the ball with the smaller density has the smaller mass (m = ρV), which is ball A.

- C

It is known that water flows faster through a narrower pipe. The speed is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area of the pipe because the same volume of water must pass by each point at each time interval. Let A be the 0.15 m pipe and B the 0.20 m pipe, and use the continuity equation:

νAAA = νBABwhere ν is the speed and A is the cross-sectional area of the pipe. Because ν is inversely proportional to the cross-sectional area, and the area is proportional to the square of the diameter

we obtain the following:

we obtain the following:

- A

This question tests our understanding of Pascal’s principle, which states that a change in pressure applied to an enclosed fluid is transmitted undiminished to every portion of the fluid and to the walls of the containing vessel. We are told that the work required to lift the bed with the patient is double the work needed to lift just the bed. In other words, the force required doubles when both the bed and the patient have to be lifted. To maintain the same pressure, we must double the cross-sectional area of the platform of the hydraulic lever on which the patient and the bed are lifted. - B

It is not necessary to do any calculations to answer this question. The open vertical pipes are exposed to the same atmospheric pressure; therefore, differences in the heights of the columns of water in the vertical pipes are dependent only on the differences in hydrostatic pressures in the horizontal pipe. Because the horizontal pipe has variable cross-sectional area, water will flow the fastest and the hydrostatic pressure will have its lowest value where the horizontal pipe is narrowest; this is called the Venturi effect. As a result, pipe 2 will have the lowest water level. - C

The continuity equation states that the flow rate of a fluid must remain constant from one cross-section to another. In other words, when an ideal fluid flows from a pipe with a large cross-sectional area to one that is narrower, its speed increases. This can be illustrated through the equation A1ν1 = A2ν2. If blood flows much more slowly through the capillaries, we can infer that the cross-sectional area is larger. This might seem surprising at first glance, but given that each blood vessel divides into thousands of little capillaries, it is not hard to imagine that adding the cross-sectional areas of each capillary from an entire capillary bed results in an area that is larger than the cross-sectional area of the aorta. - C

The data given in (C) are sufficient to determine the flow rate through Poiseuille’s law, which can then be used to determine the linear speed by dividing by the cross-sectional area (which could be determined from the radius, as well). (A) would be sufficient if we also knew the flow rate in the other segment of pipe; one could use the continuity equation to determine the linear speed. The data in (B) could be used to determine the critical speed at which turbulent flow begins, but there is no indication that there is turbulent flow. The data in (D) could be used to determine the depth of an object in a fluid. - B

The first step in answering this question is defining the different types of pressures. Atmospheric pressure is the pressure at the top of the first fluid exerted by air (at sea level, it is equal to 1 atm). Gauge pressure is the pressure inside the balloon above and beyond atmospheric pressure; gauge pressure is the total (absolute or hydrostatic) pressure inside the balloon minus the atmospheric pressure. Gauge pressure depends on the density of the fluid, the constant of gravity, and the depth at which the object is submerged. Hydrostatic or absolute pressure is the total pressure in the balloon (that is, the gauge pressure and the atmospheric pressure together). Because we are given the gauge pressure at the bottom of the first fluid as 3 atm, our task now is to calculate the gauge pressure accounted for by the second fluid. The hydrostatic pressure at the bottom of the cylinder is 8 atm. One of these atmospheres is atmospheric pressure pushing on the fluids. Another 3 atmospheres are accounted for by the first fluid that is pushing on the second fluid. Thus, the gauge pressure due to the second fluid is 8 − 1 − 3 = 4 atm. The ratio of the gauge pressures is therefore 3:4. - B

This is a basic restatement of Pascal’s principle that a force applied to an area will be transmitted through a fluid. This will result in changing fluid levels through the system. The relationship is stated as  Plugging in the numbers gives an answer of 16 N.

Plugging in the numbers gives an answer of 16 N.

- A

The buoyant force (Fbuoy) is equal to the weight of water displaced, which is quantitatively expressed as

Fbuoy = mfluid displacedg = ρfluidVfluid displacedgThe volume of displaced fluid is equal to the volume of the ball. The density of the fluid remains constant. Therefore, because ball A has a larger volume, it will displace more water and experience a larger buoyant force.

- B

Airplane wings have curved upper surfaces and flat lower surfaces, which causes the air to flow faster over the top of the wing because it has farther to travel to the edge of the wing than the air over the flat bottom surface. Increased air speed will mean lower pressure within the fluid. This will result in higher pressure below the wing and an upward force. - A

This question is a simple application of the definition of pressure, which is force per area. If pressure decreases 1 percent and area does not change, the force will be decreased by 1 percent. Note that the other measurements given do not play a role in our calculations. - C

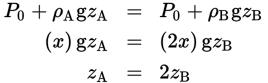

The equation for absolute (hydrostatic) pressure is P = P0 + ρgz, where P0 is the pressure at the surface, ρ is the density of the fluid, g is acceleration due to gravity, and z is the depth in the fluid. If the density of fluid B is twice that of fluid A, then the depth in fluid A will have to be twice that in fluid B to obtain the same absolute pressure:

- B

This is a basic interpretation of Bernoulli’s equation that states, at equal heights, speed and pressure of a fluid are inversely related (the Venturi effect). Decreasing the speed of the water will therefore increase its pressure. An increase in pressure over a given area will result in increased force being transmitted to the piston.