Dune in the park (photo credit 6.1)

Our van filled with the scent of freshly blooming spring flowers as we wound our way up the picturesque streets of the Berkeley, California, hills. At the crest stood Ian and Kelly Dunbar’s house—a charming Italian-style villa from the 1920s, set above a lush garden that looked out on the park and the college town below.

When I first learned about Dr. Ian Dunbar and how he had pioneered off-leash training for puppies, I had immediately wanted to meet him. Ian and his lovely wife, Kelly Gorman Dunbar—also a dog trainer—had met me for a casual dinner two years earlier. We all got along famously, but never really addressed the “elephant in the living room,” which was the very different ways each of us worked with dogs.

The purpose of this second meeting was to share ideas and information and for Ian to show me, hands-on, how his off-leash training methods work. By inviting me into their home, the Dunbars knew they would draw flak from some in the positive training community who criticize and often misinterpret what I do. And I knew that I would be spending the good part of two days as the student of someone who doesn’t agree with me in a few key areas. But I had been looking forward to this meeting for a very long time. As a father, it is very important for me to show my kids by example that we need to dialogue with people who might not agree with us instead of being defensive or shutting them out or labeling their ideas as wrong. I want my sons to make a difference in the world, not by staying away from people who don’t share their exact point of view but by talking with them and, most of all, by listening to them. This is how we learn and grow and how we make a difference as human beings, not just as dog whisperers or dog trainers. By sharing information and opening our minds, everybody benefits, and we open a door of hope for the world. I believe that world transformation begins with self-transformation, and that was the spirit I carried with me as I prepared for the opportunity to work with one of the most respected and influential men in modern dog training.

“Mind the wall,” the neatly dressed, snowy-haired Ian Dunbar chirped helpfully as we backed into his narrow driveway. Pointing to a pale yellow stucco barrier that bordered the front of the house, he casually added, “My son Jamie and I put that up ourselves.”

That homemade wall was my first hint that Ian Dunbar and I had a whole lot more in common than it might appear on the surface. After all, I am an earthy Mexican guy with a high school education who came across the border with only the clothes on his back. He is a proper Englishman with a wall covered in diplomas—a veterinary degree, with special honors in physiology and biochemistry, from the Royal Veterinary College of London University and a doctorate in animal behavior from the psychology department of UC Berkeley—and spent a decade researching olfactory communication, social behavior, and aggression in domestic dogs. Ever since I appeared on television in the United States, my critics have compared me unfavorably with Ian Dunbar, who had his own television series in the United Kingdom for five years. What could the two of us possibly share beyond our interest in dogs?

Well, it turns out that we are both country farm boys at heart—a couple of simple guys who want nothing more than to be able to plant trees in our gardens, build our own walls, and wander the countryside with our dogs. Ian’s cordial, easygoing manner put me instantly at ease.

“I grew up on a farm,” Ian sighed. “When I was a kid, I roamed the fields with my dog. I was always with the dog. And it was wonderful. I didn’t even own a leash until my first dog show.”

I nodded and wistfully drifted back to my own days on my grandfather’s farm, trudging through pastures and down dusty roads, always with a pack of dogs trailing after me. No leashes involved there either.

“And people don’t get to enjoy that today, you know?” Ian continued. “There’s not so many places now you can go with dogs off-leash. It’s happening in countries all around the world now. When I was a kid in England, if you went into a pub, there were three dogs in there: two lurchers and a Jack Russell, all drinking beer from a saucer. Now you go into a pub, you don’t see a single dog.”

“Why do you think that is?” I asked him.

“We’re becoming much more restrictive now because people are worried about dog aggression,” Ian answered. “But ironically, the increased restriction means it’s more difficult to socialize a dog now.”

The rise in the problem of antisocial, out-of-control dogs is the place where the lives of a British veterinarian and a Mexican immigrant converge. While unruly dogs drove my career path from becoming the trainer of the next Lassie to being the Dog Whisperer, the same problem inspired Ian Dunbar to develop his own original view of how to train puppies—as well as grown dogs—to become obedient off-leash. His goal is to use basic training to prevent all those behavior and communications snafus that end up with the crazy, out-of-control situations that make my television show so dramatic.

“I teach mostly noncontact techniques, and there’s a good reason for that,” Ian explained. “Most human hands can’t be trusted. Of all the humans who can’t be trusted with their hands, I guess men and children are probably the worst. They do a lot to dogs that spook dogs out. If they have the leash on, and the owner’s touching the leash, they’re usually going to end up jerking it. So I just say, ‘Well, we’ll take the leash off, solves that problem.’

“It’s one thing if you’re an experienced animal handler like you or me, ’cause you know which animals you dare touch and how you can touch them,” he continued. “The training methods that I would prescribe have nothing to do with the way I would train a dog or you would train a dog. It has to do with the fact that this is a family and there’s two children in it. They’re not necessarily going to have the observational skills that we have, or the speed or the timing, and certainly not the dog savvy. But they still have to learn to live happily with their dog.

“Most people use the leash as a crutch. It’s become a training tool which is very, very difficult to phase out. Food is easy compared to that.”

Working with dogs off-leash is my own preference as well, though the tools I’d usually employ would be my energy, body language, touch, and a couple of simple sounds. Ian Dunbar doesn’t agree with my way of using touch to correct a dog. Although he also uses body language to communicate, his tool of choice is his voice.

“I keep my hands off the dog. I never use my hands to get him to do stuff, but the hands do go on him to say thank you, to say, ‘There’s a good dog.’ But I use my voice, because the voice is the only thing we’ve got with us all the time.”

I’ve always preferred silence when working with dogs. To my way of thinking, that is how they communicate in their own world—using scent, energy, body language, eye contact, and then sound last of all. Learning Ian Dunbar’s method of training would be a new challenge for me, but an important and exciting one. Many of my clients dream of being able to use verbal commands to communicate with their dogs.

“With my malamute, I used to be able to talk to her in a complete sentence. ‘Phoenix, come here, take this, and go to Jamie, please.’ So she’d take a note and run down and find Jamie in the garden. It’s binary feedback: reward the dog when he gets it right, reprimand him when he gets it wrong, but always use your voice. Use it instructively because that’s what you want to teach. The main criterion of training is that we have verbal control when the dog’s at a distance and distracted and without the need of any training aid whatsoever. No leash, no collar, no food treats, no ball, no tug toy. When you say sit, that dog sits.”

I had brought along my trusty pit bull Junior, then two and a half years old. Like all of my dogs, of course, he was totally “balanced,” yet not what I would call trained. “I have raised him since he was two months old,” I told Ian. “I can’t take the credit—my dog Daddy, who passed away a few months ago, did most of it. Junior pretty much took over Daddy’s way of being, and I just guided them a little bit. And so Junior has no ‘sit’, no ‘down,’ no ‘stay.’ ” I demonstrated for Ian the two command sounds that Junior knows: a kissing sound that means “come, yes, good,” and my “tsssst” sound, which means “I don’t agree with what you are doing.” “Those are the only sounds he knows, but I would like you to show me how you would teach him commands.”

Welcoming the challenge, Ian invited Junior and me into his airy, light-filled living room and offered me a seat on a thick-cushioned chocolate leather sofa.

“Before we start,” Ian began, “my grandfather taught me that touching an animal is an earned privilege. It’s not a right.” I smiled, feeling even more at ease. There was one more thing that this charming Englishman and I had in common—grandfathers who shared with us their wisdom in the ways of Mother Nature. “And the most dangerous part on a dog is that red thing around his neck.” He gestured at Junior’s collar. “About twenty percent of dog bites happen when the owner touches that. Happens when an angry owner grabs a collar and gets in the dog’s face—‘You bad dog.’ ” Ian had spent several years researching the causes and effects of domestic dog aggression, so he knew his statistics.

To avoid that potentially volatile situation, Ian uses a treat in hand as a temperament test. “I take a little time. See, I don’t know Junior. He has no reason to like me. So I want to make sure he’s okay. If Junior here takes the treat, I say, ‘Gotcha. We’re off and running. We’re gonna work with you today.’ ” As Junior took the treat from his hand, Ian took Junior’s collar in the other, then repeated those two motions a few times. Ian was conditioning Junior to associate his hand with the pleasant experience of getting the treat. This kind of association can also be a lifesaver, he added.

“You know, we could have an emergency: he could be jumping out the car window on the freeway, and I grab his collar quickly. He’s not going to react by biting me; his first thought is, ‘Where’s my treat?’ ”

Ian explained to me that his process begins with a very simple four-part sequence: (1) request, (2) lure, (3) response, and (4) reward.

“So we say, ‘Junior. Sit.’ That’s number one, the request. And then we lift the food up.” Ian bent his arm at the elbow and lifted the treat lure up above Junior’s head. “Now his butt goes on the ground. That’s the response. So now, ‘Good boy. Take it.’ We reward.”

Ian then asked Junior to stand, moving his hand with the treat slightly over to the side. “When he stands, we say, ‘Good boy,’ and then we give him the treat.” Ian repeated this sequence one more time, with Junior responding nicely.

I noticed that Ian would hold the treat right up against Junior’s teeth but wouldn’t give it to him right away. “The longer you hold on to it,” he explained, “you reinforce this really nice, calm, solid sit-stay.”

Junior was doing just great with the sit-and-stand routine. Next, Ian gave Junior a much tougher assignment—the “Down.” Saying the word down, Ian moved his hand holding the treat to the floor. Junior followed with his eyes but didn’t go into the down position.

“It’s all right,” Ian said kindly. “This one is a little harder.” He started the routine again with “Sit,” using just his arm movement and not producing a treat reward.

“See, I’m already phasing out the food lure for the sit signal. That’s really important. Phasing out the food is the most important thing that you do in training, and this is what a lot of people aren’t doing. So the dog learns: if my owner has food, I’ll do it; if he doesn’t have food, I won’t. Just like there’s no point in having a dog trained that is only obedient if he’s on-leash, there is no point in a dog that’s only obedient if you’ve got food on you. We’ve got to make sure that he will listen to us even when we don’t have food.”

I looked over at Junior proudly. There he was, attentive, alert, in perfectly poised pit bull posture. He was just waiting for the next command.

“Look at Junior,” Ian said, echoing my thoughts. “He’s thinking, ‘What do I do next?’ So nice and calm. So we’ll try with the down again.” Ian moved his arm down, and this time Junior followed with his whole body, but very awkwardly. Ian still rewarded him with the treat and encouraged him in a warm, comforting voice: “Good dog. Good boy. There’s a very good dog. I’m very impressed by that. Junior, sit.” When Junior sat right up again at only the verbal command, I couldn’t help but pump my fist in the air.

Ian laughed. “You’re proud of him, aren’t you? Okay, Junior, down.” Down Junior went, folding into the floor one clumsy body part at a time.

“Good dog,” Ian said, “even though that was more of a collapse than a down. I’ll reward you anyway. What we’re doing here is teaching Junior ESL—English as a Second Language. We’re gradually working on these three commands: ‘sit,’ ‘down,’ ‘stand.’ ”

As he continued to work Junior with the three commands, Ian explained to me that by teaching a dog these basic commands—most important, a reliable “sit”—he can solve 95 percent of potential behavior issues that could arise with his dogs. That foolproof off-leash “sit” is at the core of Dunbar’s training philosophy. “If he’s about to run through the door, jump up on you, chase the cat, get on the couch, jump out of the car before you want him to … ‘Junior, sit.’ End of problem. If he’s about to chase a little girl in the park because she’s got a hamburger, even though Junior’s just playing, because he’s a pit bull, imagine what people would think. ‘Junior, sit.’ End of problem.”

Ian went on to explain that, even though the fail-safe “sit” is the most important thing to shoot for, he works a dog with the three different commands so that the dog actually learns what each word means. If he just does “Sit, stand,” or “Sit, down,” the dog can outsmart him by predicting what command will logically come next. By switching up the commands, from “Sit, stand, down,” to “Stand, down, sit,” in as many variations on the sequence as possible, he forces the dog to actually listen to the sounds coming out of the trainer’s mouth and figure out which sound attaches to which behavior.

“It’s not the words themselves that are important,” Ian explained. “Kelly teaches her dogs in French. You could use Spanish. I use words so that the owners understand the meaning. But for the dog it doesn’t matter. After just half a dozen or so associations, a dog can understand the meaning of a new sound or word.”

“How do you do the transition from him expecting the food to not getting the food?” I asked Ian.

“First we phase out food as a lure, and then we phase out food as a reward,” he responded. “Okay? Junior, down. So, you see, I don’t have food in my hand. He’s following my hand, but he went down, so I’ll give him the reward from the other hand.” Ian continued working with Junior, demonstrating the many different ways he phases out food lures. First, he would change the hand in which he kept the food so that the dog was responding to the hand signal but not the food. Next, he’d put the food in his pocket or on a nearby table and use it as a distraction and a reward. Junior knew the lure was there, but he couldn’t focus on it because he had to pay attention to Ian’s commands and signals. Ian even gave me the food lure to hold, which was an even bigger distraction for Junior, since I’m his owner and the one he is used to listening to. Also, Ian rewarded Junior with the food only intermittently, and only for Junior’s best responses, so Junior never knew when or if a reward was coming. Throughout all these variations in how he used food as a reward, Ian continued to reward Junior verbally. “Your dog knows what ‘Good dog!’ means. Not necessarily the words, but your tone of voice, and your face, and your body language. ‘Praise your dog when he gets it right,’ I tell people. Too many people only talk to their dogs when they get it wrong. Dogs do so many more things right than wrong.”

Though Ian advises dog owners to phase out treats for training as soon as they see the dog making the connection from a command or hand gesture to the desired behavior, he thinks that treats still have an important place in an overall plan for socializing a dog, especially to strangers and guests. “Keep treats in the house for guests, so that your dog always associates new people coming in with good things happening. Your guests can practice teaching commands too, which is good for the dog. And absolutely save the best, tastiest treats for kids to use. That way, when your dog sees a child, he associates it with the absolutely most wonderful reward.”

As Ian repeated the three-command sequence, Junior was definitely getting the hang of the process, but his body was moving too slowly for Ian’s tastes. “I feel like we’re in slow motion. I want to show you a really fast dog doing this.”

“Junior, buddy, what are you doing to me?” I thought to myself. He wasn’t doing anything wrong, of course, but for my own ego reasons, I wanted Junior to be the most perfect dog in the world for his lesson with Dr. Ian Dunbar! I mean, how would it look if the Dog Whisperer’s number one right-hand dog was deemed “slow”?

“He’s a smart dog,” Ian replied, sensing my dismay. “And a smart dog can be harder to train. I mean, he was outthinking me in a number of ways. He says, ‘No, you don’t have food in your hand, it’s in the other hand.’ I was trying to move too fast with him. So, yeah, he’s got a good IQ. He’s a smart dog.”

“Thank you, God!” I exclaimed.

Ian’s wife, Kelly, brought in Hugo, a happy-go-lucky, high-energy French bulldog with huge, expressive brown eyes. Kelly is the founder of Open Paw, an international humane animal education program for pet owners and shelters, and Ian says that she is a far better trainer than he is. My observation was that these two top trainers share the same overall training philosophy but have different personal styles. While Ian is effusive, a bit goofy, and gives lots of continual verbal feedback during a session, Kelly is a little more like me in that she is quiet and reserved until she feels she’s achieved her objective 100 percent. She works with subtle gestures and very few words. I thought about Mark Harden’s advice to trainers to “be yourself first, but be your best self,” concluding that both Ian and Kelly are absolutely their best selves working with the dogs that they love. That is the mark of a great handler—maintaining personal integrity at all times.

Calling Hugo over to the sofa, Ian said he would show me his training routine with a dog that had much faster reflexes than Junior. I swallowed my ego and tried not to take the comparison personally. “This is just like I was doing with Junior, but faster,” Ian said. “So, first we work with food in hand. Sit. Down. Sit. Down. Sit. Good. Stand. Good dog! Down. Sit. Yeah, you’re missing it, dude, I’m sorry. Sit. Down. Sit.”

I was blown away by the feisty Frenchy’s speed. Ian rattled off the words in rapid-fire succession, and Hugo moved like lightning. “So,” Ian continued, “once we get him as fast as this, I know I can cause the behavior just by moving my hand. Now watch this.” Ian called out six quick command sequences, and Hugo responded perfectly. At the end of the long sequence, Ian rewarded him.

“Now, this is his first treat he’s getting after all that behavior. So I was using the food as a lure to teach him how my hand moves, but now that he has learned the hand signals, I can put the food in my pocket and use it only occasionally to reward him for faster or more stylish responses. Then we go cold turkey on the food and phase it out completely. We use verbal commands and hand signals to get him to respond and then reward him with life rewards. For example, ‘Hugo sit,’ … and then we throw a ball. ‘Hugo, down,’ … and we pet him. Or we ask him to sit lots of times while playing tug-of-war. We use food as a lure to teach him what we want him to do and to get the speed, and then we totally phase it out, first as a lure and then as a reward. From then on, we use life rewards to motivate him to want to comply.”

The next level of Ian’s training involves phasing out the hand signals so that the dog responds only to the verbal commands. “Now, this is the hard bit,” he told me. “Because, as you always say, Cesar, body language is the way dogs read us. They sniff, they see life through their nose, or watching the movement of people or other dogs or animals, and so we think, ‘Oh, he’s learned what ‘sit’ and ‘down’ and ‘stand’ mean,’ but he hasn’t, he’s actually learned what the hand and body movements mean.

“So this is where the timing is really important. We have to say the word, a very short pause, and then [do] the hand movement. So it has to be like this: ‘Hugo, down. Good.’ Now there, he was going down before I did the hand movement, which is showing he does have some comprehension. Eventually, he will anticipate the hand signal and he will respond when I ask him to verbally, and that’s when he’s starting to actually learn the meaning of words. And that’s so important for dogs, because at home they’re off-leash, their back is turned, they’re in another room, and so verbal communication is the only way to go. You can’t touch the dog’s collar or give a hand signal—he can’t see it. So that’s why verbal control is really important, but it’s the most difficult thing to teach. It takes usually about twenty trials before he can make the connection. So you can see the learning in progress.”

I observed that when Ian commanded “down” to Hugo, while he was phasing out his hand signals, he made a tiny, unconscious movement of his head. He laughed out loud when I busted him. “That’s bad, but we all do it. What I meant to do is do this absolutely still. ‘Hugo, sit. Good dog. Hugo, down. Good boy!’ So I was better there, was I?” he asked.

“Good boy!” I told Ian.

“You have to minimize the signals you are sending, with your body or even your eyes. And that’s where, when the dog doesn’t do it and people think, ‘Oh, he’s dissing me, he’s being disobedient,’ then they start to get frustrated, and they get mad at the dog, and the relationship goes downhill. But that’s not what’s happening. I mean, look at Hugo now—is he being disobedient? No, he’s sitting right in front of me, looking at me, but he just doesn’t understand yet because I haven’t done sufficient training with him.”

Kelly, who was standing by quietly watching us with Hugo, added her own thoughts on the subject. “I think it’s an important point that people don’t realize all the signals they are giving their dog with their bodies and their heads all the time,” she mused. “So then, when the dog isn’t looking at them, they’re saying ‘sit’ or ‘down,’ and the dog doesn’t respond, now the dog is bad. Or they may be saying one word, but their body is saying something else. So that’s why verbal commands are so important, but so few dogs have adequate verbal comprehension. They’re just so very good at observing us.”

“And I should say,” Ian added, “Hugo is much better trained in French. Kelly uses French, and he is a well-trained dog, it’s just he doesn’t know English when I speak it very well.”

“Is it because of your accent?” I asked him with a wink.

“No, no.” Ian laughed. “Actually, I try not to train him that much so I can use him as a demo dog, because he’ll be more likely to make mistakes. One of the most endearing things about dogs is that they are individuals. They’re not robots, and to me, when they do it their own way or make a mistake, it’s almost as endearing as when they do it right, as long as it’s not dangerous. The reason I like working with Hugo is to show to people that just because your dog doesn’t do it, doesn’t mean to say he’s bad, or not smart. It means you need to train him more and keep working at it, because it’s the learning process.”

Before we moved on to the next stage of training, Ian offered me a go at teaching Hugo in Spanish, to demonstrate how dogs learn words. “Just use your hand signals, okay? ’Cause Hugo knows those.”

I raised my arm, saying, “Hugo, siéntate, Hugo, siéntate. Hugo, échate. Hugo, párate.” He responded quickly to every command.

“We have a multilingual dog!” Ian cheered. “This is his first Spanish lesson. He speaks French, he speaks English, and now he speaks Spanish. And that is what training is all about. It’s teaching our languages as a second language to the dog. Whether it’s Spanish as a second language, English as a second language, or French as a second language. Then we can communicate to them what we’d like them to do.”

“But again, it’s really not the words themselves the dog understands, right?” I asked.

“Whether they really understand the actual meaning of a word—we can have a discussion about that for hours,” Ian responded. “What we do know is, you can teach a dog if you say a word: he will do a certain thing to a certain amount of reliability. But dogs learn differently from people, of course; they don’t generalize. For example, I taught my son how to travel in an airplane by sitting ourselves in chairs in front of the TV and strapping ourselves in. And we did a practice run before we got on the plane to London. That way, we could work out all the things that could go wrong, like, ‘This is boring,’ ‘I want to pee,’ ‘I want to go to the toilet,’ ‘I want to eat,’ ‘I’m thirsty,’ ‘I want to watch a movie,’ ‘I want to read a book.’ So we rethought it all together, and then when we did the real plane flight it was great. Humans can do that. On one trial they can generalize. Dogs can’t. If Kelly teaches the dog in the kitchen, what you’ve got is a good kitchen dog with Kelly. I come in the kitchen, the dog won’t listen to me.

“The dog has to be trained by everyone in every situation. That’s why the very best training exercise you can do is, when you’re walking your dog, every twenty-five yards stop and ask him to do something. ‘Sit’ … ‘Down’ … ‘Speak’ … ‘Let’s go.’ And so each little training episodette is in a different scenario, outside a schoolyard, a basketball pickup game, a leafy street with squirrels, lots of skateboards, and kids and what have you. And after a while, you know, one three-mile walk, the dog comes back and realizes, ‘Oh, you mean sit always means sit? Everywhere? Never would’ve guessed that!’ ”

The next step in Ian Dunbar’s training process is to transition from food rewards to what he calls “life rewards.” Life rewards can be anything and everything that gives a particular dog’s life meaning, the things that bring him the purest joy. “We start with food as a reward because it’s convenient. But it doesn’t compete with the dog’s real interests, whether that’s playing at tug-of-war, sniffing, or playing with other dogs,” Ian explained. “Here’s the secret to a highly reliable dog: make a list of the dog’s ten favorite activities; you put it on the fridge. And that’s when you train the dog. You let him outdoors to sniff, then teach ‘Come here, go sniff. Come here, go sniff.’ Or ‘Sit, go sniff.’ You let him play with other dogs. That’s probably the biggest. And then you just say, ‘Come here,’ or have him sit, then release him to go play again. And at that point, these wonderful activities—they’re part of the dog’s life, the dog’s quality of life; rather than becoming distractions that work against training, they now become rewards that work for training.”

I immediately fell in love with Ian’s concept of life rewards, because it is such a clear way for people to understand and honor the animal nature of their pets. It is also a way to practice a kind of leadership with a dog that can blossom into a true partnership.

“Ninety percent of training is not teaching the dog what you want him to do; it’s teaching him to want to do what you want him to do,” Ian continued. “So eventually you end up with a self-motivated dog. And you say, ‘Come here,’ and he says, ‘Yeah, I’ll do that.’ Why? ‘Because Cesar called me. I’m not doing it to please him; I’m doing it to please myself.’ Because it’s a dog and a person living together, it’s a relationship. I look on training like basically tango. You’re dancing tango. And the two of you have this beautiful, exquisite choreography, and one’s meant to be leading, but often the other does. You’re following each other, you’re changing roles, but you’re enjoying doing something, living together. And that to me is what dog training is.”

Throughout his training session, with both Ian and me, I noticed that Hugo had been looking yearningly toward Kelly. “So a life reward for Hugo would be to go see Kelly?” I asked.

“You got it,” Ian agreed. “Let’s try it. Hugo, sit. Good dog. Go and see Kelly!” Immediately after sitting, Hugo sprinted across the room and jumped into Kelly’s arms.

“Good dog! See?” Ian asked. “That makes him really happy. So running to Kelly, looking for odors, playing tug-of-war, those are the biggest rewards for the dogs in our house.”

“It’s like, honor nature, honor your house, honor your family, and think of them as a reward,” I mused.

“That’s a very nice way to look at living with people and dogs, isn’t it?” Ian agreed. “They are the reward.”

Dogs love challenges, and they love playing games. I’ve always believed that training and even rehabilitating dogs should become a game wherever possible. Ian Dunbar has come up with an endless assortment of creative ways to use games as both training tools and life rewards for his dogs.

One of the first exercises Ian demonstrated for me made use of the playfully competitive nature that comes naturally to dogs in order to teach and improve their responsiveness to commands. He brought in Dune, their magnificent purebred American bulldog with a lean, sinewy body the color of burnt sienna and an enormous head that reminded me a little of Daddy. Ian called Dune and Hugo to him so that they both sat poised in front of the couch while he held up a treat. Then he tested their knowledge of a verbal command while making it a contest.

“So I say, ‘First dog to … down!’ ”

Both dogs hit the floor, but the larger Dune made it first. “Oh, Dune won that. Hugo had a start on him. Okay, ‘First dog to … sit!’ No, I didn’t say ‘scratch,’ Hugo, I said ‘sit!’ ”

Ian always left a long, dramatic pause before the actual command word, so that the dogs couldn’t anticipate him. Instead, they stayed at rapt attention until they heard the cue. It was a wonderfully creative and fun way of making sure the dogs knew the actual words for the commands, not just the body signals.

I always warn my clients about playing tug-of-war with their dogs, particularly powerful breed dogs like pit bulls or rottweilers or insistent dogs like bulldogs. If you don’t understand how to control your dog’s intensity, a tug-of-war game can become a power struggle between you and your pet that you don’t want to encourage. Ian Dunbar, however, has conditioned both Dune and Hugo to be able to play this tricky game, while he retains total control of the “on-off” switch. In this way, he does several things at once: he reinforces his leadership position with them, he polishes their understanding of verbal commands, and he gives them a fun life reward that they relish.

Kelly brought Ian a toy that they fondly call “Mr. Carcass”: a stuffed replica of a rodent carcass, it resembles a fuzzy piece of roadkill. Ian placed the toy in front of Hugo, who waited politely until Ian said, “Okay. Go take it!” Immediately, Hugo dug into the well-worn toy and began to pull with all his weight, while Ian continued to encourage him: “Pull. Good dog. Okay, pull. Okay, good dog, good dog. Okay, Hugo, thank you.” The moment Ian said, “Thank you, Hugo, sit,” Hugo backed off and went right into a sit. Right after Hugo complied, Ian repeated the command—“Take it!”—and Hugo dug right back into Mr. Carcass again. “That’s the reward. You see, it’s much better than a food treat. Go on, pull. Thank you, guys. Dogs, sit.

“I really want them to enjoy this, because this is the reward for the sit. But then I very calmly say, ‘Thank you. Good dogs. Dogs, sit.’ When you’re playing tug, you’ve got to have lots of rules; you can never touch it unless I say, ‘Hugo, take it.’ The learning process would be like this: ‘Take it,’ and then we’d tug, and then I’m going to say, ‘Thank you,’ and go absolutely still. And when the dog lets go, ‘Good dog … there’s a good dog’ … maybe a food treat to begin with. And then of course, the bigger reward, ‘Take it.’ But the rules here are, you can never touch my hand. If you touch my hand, it’s finished, the game’s over. They never touch the tug toy until you say, ‘Take it.’ And they always let go when you say, ‘Thank you.’ You can see how much the dogs enjoy this, so they’re never going to touch your hand. This kind of exercise takes a lot of patience to perfect. What I’m interested in is, I can start the activity and I can stop it. Once again, it’s a trick in dog training where you take the distraction that’s working against training and you turn it into a reward that works for training.”

The flip side of this game was another toy Ian produced called “Mr. Mousy.” Compared to the ratty, ripped-up Mr. Carcass, Mr. Mousy looked brand-new and had the kind of high-pitched squeaker inside it that can make dogs go crazy. “This toy isn’t for tug. It’s for teaching limits. So I let them touch Mr. Mousy, ‘kisses only.’ And this is training a dog that there are things they can touch but are not allowed to bite.” Ian squeaked the toy but carefully controlled the interaction so the dogs gave it gentle respect. “You can use this exercise in preparation to bring a kitten or a new puppy or even a baby into the house, when you’ve got to practice on something. So this toy will live forever.”

I asked Kelly how she controls the intensity of the dogs’ play—how intense is too intense? “You do keep an eye on the intensity, but from a training perspective, the frequent interruptions keep playing and training from becoming mutually exclusive. So you use frequent interruptions if your goal is to use play as a reward for right behavior, and then less frequent interruptions if they’re just having a good time and everyone’s cool.”

The Dunbars use the “tug” play session as both a training exercise and a game, and that is also the basis of how they teach owners to control a dog’s bad behavior—by making the behavior its own reward, and then putting that reward on cue.

“Everything that people think is a problem—‘Oh, my dog barks,’ ‘My dog tugs at things,’ ‘My dog jumps up,’ ‘My dog runs away’—they aren’t problems anymore. They’re just games that you play with the dog to always reinforce the ‘sit.’ And once you’ve got that one emergency command, ‘sit’ or ‘down,’ you can stop anything that’s going on. You just say, ‘Sit’—end of problem. And we’re back in control again, so we can then praise the dog.”

For instance, if a dog is compulsively barking, you can put barking on cue. “You use the same one-two-three-four formula—request, lure, response, reward,” Ian explains. “For example, say, ‘Speak,’ have an accomplice knock at the door, and when the dog barks, praise and reward. So then the dog learns, ‘Aha, when he says, “Speak,” someone knocks on the door,’ so they learn to speak when you say so.

“It’s difficult to teach a dog ‘shush’ when people are at the front door because the dog is so excited. But once you’ve got ‘speak’ down, you may teach ‘shush’ when it’s convenient for you. You can drive somewhere in the middle of nowhere where you’re not annoying anyone, tell the dog to speak, and then, when you want the dog to shush, say, ‘Shush,’ and let him sniff a food lure. When he sniffs the food, he’ll stop barking. As soon as he goes silent, praise him gently for a number of seconds and then give him the food as a reward for shushing. Then you can practice it at the front door with the same basic one-two-three-four sequence. Say, ‘Speak,’ lure him to speak, knock-knock-knock on the door, he barks, ‘Good boy, there’s a good boy,’ then say, ‘Shush,’ waggle the food in front of his nose so he sniffs, and as soon as he goes quiet, ‘Good shush, good shush,’ and give him the reward. Now you have a dog that will inform you when someone is on your property, but he will shush when you ask.”

“So you are being proactive about it,” I said. “Before the dog drives you crazy.”

“Exactly,” Ian replied. “They like barking so much, I can now use that as a reward in itself. I remember once I was driving back from San Francisco and the bridge was all blocked. I was there for two hours in the traffic, and I had my malamute, so I opened the sunroof, and I said, ‘Omaha, ooww!’ and he put his head through the roof and went, ‘Oooouuuuwww.’ And there was a guy in a BMW next to me. He comes through his sunroof and he howls. And everybody on the bridge got out of their cars and howled. It was just a moment in time when everyone howled. And so you use barking as a reward.”

Ian describes his oldest dog, Claude, as a “big red dog.” “We think he is a cross between a rottie and a redbone coonhound,” says Ian. Claude is about twelve years old and wasn’t raised from puppyhood by the Dunbars, as their other dogs were. “Claude was asocial when we got him. So he plays and breaks a lot of rules. He’s the top dog here.”

Claude has another interesting quirk—he’s crazy for lettuce. This senior dog used to have a habit of putting his nose down and ignoring his human on the walk, but once Ian made the lettuce discovery, he realized he had a brand-new motivating tool. “When I go for a walk with him, I’ll bring a little bit of lettuce, and while I just stand still and bring the lettuce out, he sits and looks at me, which otherwise he never does on a walk. So, you know, you need to be inventive—if kibble isn’t working, if praise isn’t working, find something else that excites him.”

By using his creativity and finding that special something that turns his dog on, Ian created a whole new technique, “heeling with lettuce.” He let me try it. While holding the lettuce, Claude worked perfectly by my side, then heeled when I turned and looked at him. “Sit,” I said, and obediently he sat. I gave him a bite of lettuce, and we continued on.

“It’s a Cesar salad!” I said.

“And this is how all training should be,” Ian remarked. “When you’re heeling your dog, it should be like you’re walking hand in hand with your kid, or arm in arm with your spouse.”

I was thrilled to discover that the Dunbars are as enthusiastic as I am about giving nose work to their dogs—as a game, a physical-psychological challenge, and a training exercise. Scent is the most primal of a dog’s senses, and by making sure a dog stays connected to his nose, you are honoring the deepest part of the animal-dog in him. You, the owner, are showing your dog that you care about his doing the things that matter the most to him, not just what matters to you as a human.

Ian Dunbar has done extensive laboratory research into the olfactory abilities of dogs. “Their sense of smell is so unbelievable, we can barely comprehend all they can smell,” he said. “I mean, they can come into a room and figure out, ‘There’s eight people here, and one of them is scared.’ They know that immediately. You can be twenty-five yards away, and they would notice it. Nose work is when all the training comes together and there’s no need to reward him doing this.”

“Your dogs get to use their favorite sense,” Kelly added, “and they get so much joy out of it, and it really exhausts them, just like exercise. And it gives them a job too. Pet dogs don’t have jobs anymore. It gives them a little work that any dog can do at any age. It’s not something like agility, where they have to be in great shape.”

“People in New York might say, ‘Well, my house is very small,’ ” I remarked. “But this exercise—it doesn’t matter how small your house is, right?”

Kelly nodded enthusiastically. “You can do this anywhere: you can do it indoors, you can do it outdoors at the park. Even small rooms can become more challenging because the odor really pools, so a small room is actually a good challenge for a dog.”

While the dogs looked on excitedly, as if they knew that their favorite game was coming up, Kelly explained to me their method of doing nose work. They take a piece of birch bark—an herb with a root-beer-like scent—in a tiny aerated metal container, and then they hide it somewhere in the room while the dog is outside.

Then they let the dog in and show him his reward. “For Claude, it’s lettuce. For Hugo, it’s food,” Ian said. For Dune, a tug game fanatic, the ultimate reward is a huge green stuffed crocodile—CrocoBob. Next, they give the command, “Find it.” When the dog finds the odor, they reward him with whatever his treat of choice may be.

“The way we prepared Dune for this was, we had to transfer that association with the toy to the odor,” Kelly explains. “So first we taught him to search in general with just looking for his toy. And then we paired the toy with the odor, so he learned that the odor meant the croc.”

When they were ready to do the exercise, Ian let the dogs out of the room while Kelly hid the scent box among some books on a side table. When Dune came into the room, it didn’t take him more than a minute to home right in on it. On the second go-round, they hid the scent under a pillow on a chair by the large open fireplace. This location was a little more challenging, Ian explained.

“This is kind of hard there, because all the air will be going into the fireplace and up there, so it’d be sucking the odor out, so he may be getting a scent of this, far away from where it is,” he said. “One of the biggest mistakes people make when they’re doing scent training, they use too much scent, and then it goes, whooom, and floods the room.”

The first place Dune went when he came back into the room was the place where he’d found the odor on the last go-round. “There’s a lingering odor there,” Kelly said, “but he’s got to find the odor where it is in the highest concentration.” We all watched a very focused American bulldog try to figure out where the scent was coming from. “It tells you a lot about how the air travels in the room,” Kelly said, watching all the places Dune traveled on his quest. I could see the intensity of his search and the pure joy of the challenge. He was in the zone. “This is a good way for owners to learn how to read their dogs,” Ian commented as Dune began to hone in on the location. “We can see that he’s hit the scent but he can’t quite work it out.” Just under two minutes after entering the room, Dune hit on the scent and got his reward.

“The wonderful use of this is, once you train the dog first to find what he likes—Hugo finds food, Claude finds lettuce, and Dune finds his tug toy—then the next step is, now they can find the remote control for the telly, they can find your glasses. I mean, I’m always losing them. I can say, ‘Where’s my glasses?’ They can find your car keys, and now you can take your dog for a ride in the car. So it has great uses, and I think it’s the best mental exercise for a dog. I would put it above a treadmill in terms of exercise. I would say sniffing and working out the olfactory puzzle is more important than physical exercise on the treadmill.”

As my viewers know, I believe that there is no substitution for a dog getting primal, physical exercise by walking outside with its owner. But as Ian points out, mental exercise is every bit as important when it is a structured challenge like the Dunbars’ nose-work drills. This kind of challenge can keep a dog from getting stressed or bored on a rainy day, a hot day, a snow day, or any day when the owner can’t physically be outside with the dog. It can be done by dogs of any physical ability, or even any age. I thought back to Daddy. When he was so old that he barely had any eyesight or hearing left, his nose was still as active as ever.

“You can see that the task is the reward,” Ian pointed out. “It’s not a job anymore. This is kind of like watching movies for the dog. The activity now becomes the reward. He’s just so happy using his nose, the best part of his body, and it’s a training exercise, yet it’s a thrill for him. It’s what all training should be, the very reward.”

Where the strength of your off-leash training really comes into play is in the real world, out on the street or in a park. To demonstrate the practical applications of everything he’d been explaining to me at his home, Ian took me with him and Dune down to the lush Berkeley Codornices Park.

“Training has to be stronger than instinct, stronger than any urge, stronger than any distractions. And there are a lot of distractions out here. Scents especially. I mean, the dog’s nose is amazing. I did research on what they smell. They can obviously tell male from female, neutered from intact, individual dog from individual dog, strange male urine from males that they know. It’s their form of pee mail. That’s basically how dogs communicate. Like we have e-mail, dogs have pee mail, right? And it’s just as important to them. They’re social animals.”

Ian pointed to Dune, who had wandered over to a plot of leafy groundcover and was sniffing away with abandon. “He is checking up on all the guys he’s met on his walks. He’s not been to this park for probably a year. And he’s smelling now, thinking, ‘Oh, that’s Joe! I met him way up on Shasta just three weeks ago. Wow.’ You know? And it’s like you’ve been away for a holiday, and now you’ve got all this e-mail to check.

“The thing is,” Ian continued, “it’s so important to dogs that it will become a distraction. And that’s why we have to turn it into a reward in sessions like this.”

Ian showed me what he meant by turning the distraction of the park and Dune’s intense sniffing into a “life reward” that works for his training, not against it. The first requirement is that the owner have a reliable “sit” down pat. The sit, as well as the recall, should be rehearsed at home, starting in a small area.

“They should practice this in the bathroom, in the living room. They should do this in the backyard, or in a smaller area where they can control it. Then they bring in a friend’s dog, so now the distraction is the off-leash area and the other dog is the temptation. And then all of these things which were distractions, which cause the dog not to behave, and so make the owner so mad and cause them to punish the dog, become a reward instead.”

Ian demonstrated with Dune how his method works. He let Dune off-leash to wander around at his pleasure, but kept an eye on him. If Dune started to wander a bit too far, Ian called out, “Dune, sit.” The faster Dune responded, the more quickly Ian would release him from the sit to give him his “life reward” of sniffing in the brush afterward.

He’d release Dune by saying, “Go play.” I noticed that Kelly used the word free to mean the same thing. If Dune did not sit right away, Ian would increase the urgency in his tone of voice until Dune sat, and then he would call the dog toward him and instruct Dune to sit again. “If the sniff’s out there, then when he sits immediately, he gets the reward back immediately. However, if he doesn’t sit immediately, he’s going to have to come towards me and repeat the exercise until he sits following a single command before being allowed to resume exploring once more. So eventually, the dog learns, you know, if you just sit when they ask, you can have a great time out here.”

Ian and I both agree that when you are with your dog in the outside world—be it at an off-leash park or sitting with your dog on-leash at a sidewalk café—your dog should have at least a part of his attention focused on you at all times. Since Dune and Ian hadn’t been doing walks in the park together for some time, at the beginning of our excursion it was clear that Dune was not complying on that front. “He’s not totally with me yet. So there’ll be more training than play. But once he’s on the ball, and when I say, ‘Sit,’ he sits. Well … then it’s all walking and sniffing.”

One of the reasons this exercise is so challenging is that a dog’s sense of smell is so strong that when he’s smelling something, he often won’t even hear or see you. And it’s challenging for a human because it’s easy to become impatient or emotional when you think your dog is ignoring you.

“The ears are turned off. The dog literally doesn’t hear you if he’s sniffing,” Ian asserts. “I liken it to my son or my wife. They don’t always do what I ask them to do right away, but I don’t want to get annoyed or upset with them. I love them. And the same thing with the dog. Okay, so you didn’t sit on my first command. It’s no big deal. But you’re going to do it. And once you’ve done it, you’re going to repeat the exercise until you sit following a single command. I look on training as a lifelong process.”

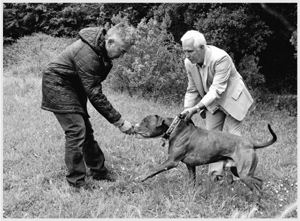

Dune searches for a scent. (photo credit 6.2)

Ian Dunbar maintains his hands-off philosophy whenever possible, even in the park. “I use my voice in training, and I use my voice as a reprimand as well. It’s a form of punishment, but it is a non-aversive punishment. But you can do a lot with your voice, different variation of tone, which the dog understands. And I have a method that is really useful, in that I always code to the dog how important each command really is.”

That coding can be done with energy level or tone of voice. I witnessed Ian varying his tone and volume a lot during the course of our time together, all with the intention of getting a different response. One of the creative ideas he suggested was to practice shouting at the dog in an urgent tone of voice in a normal, calm situation at home, and then rewarding him lavishly. “You simply shouldn’t train if you’re in any way upset. It’s not going to work. However, you should train the dog to listen to you if you are upset or frightened. The first time an owner uses the ‘sit’ command as an emergency, they might shout, ‘Rover, sit, sit, SIT!!!’ And the dog says, ‘I don’t think so—you’re shouting at me!’ The dog just panics and runs off. So we do practice commands delivered when the owner uses a loud voice, but all it means to the dog is, you’re going to get a better reward. That way, if you are outside and your dog runs into the street, when you call him back in a loud, urgent tone of voice, he doesn’t think you’re suddenly mad at him; he understands the urgency and that there is a bigger reward coming if he obeys.”

The other way Ian accomplishes “coding” is what he calls “dog con one, two, and three.” He uses both tone of voice and the name he calls the dog to indicate the importance of what he’s asking the dog to do.

“So, by saying to Omaha, ‘Ohm, come here,’ he understands that it’s not a command but a suggestion. And I live with dogs about ninety-nine percent of the time at ‘dog con one.’ For instance, we’re on the couch. ‘My buddy,’ I say. ‘Ohm, settle down. Ohm, move over on the couch.’ And he has the option of refusal. Whereas if I really want him to do it, I say, ‘Omaha, sit.’ And as soon as I call him ‘Omaha,’ he knows he must follow the next instruction. No exceptions. There’s no argument, there’s no bullying, there’s no physical forcing. But if I say, ‘Omaha, sit,’ the next thing that will happen before life as he knows it continues, he will sit, and then he will repeat the exercise until he sits following a single request. And then I’ll let him continue on with his life again. That is, ‘dog con two.’ Letting a dog know that he can relax most of the time increases his reliability when you really need it.

“You find a lot of parents do it too. Especially in multilingual families. They will suddenly change from English to Spanish. You know they’re saying, ‘Johnny, put that down,’ ‘Johnny, don’t touch that,’ ‘Johnny … Juan, siéntate.’ And as soon as they change languages, the little kid responds pronto.”

I cracked up at that—because that’s how it works in my own family.

“Then finally we have ‘dog con three,’ which is what we do when we’re on TV or in the obedience ring. When I call Omaha Wahoo, he knows it’s showtime, so he’s got to be looking at me, smiling, with his tail up. There are times when you want really good obedience, the best you’ve got. And so we can signal those times to the dog, by using a different name or a different command.”

While we were in the park, Ian demonstrated how he uses a reliable “sit” at a distance to communicate with Dune off-leash. He prefers teaching pet owners to have a totally reliable sit before he teaches the more difficult recall. “My major goal is to get an owner to be able to perform a reliable sit in all situations. I teach an emergency sit or down. Say the dog’s roaming, and here comes a child. If one parent says that this dog jumped on the kids, he becomes a legal entity right there. So I’ll say, ‘Dune, sit.’ I can leave him there until the child leaves. He sits and stays because he knows that this is our routine—‘Ian tells me sit, and I always do this. I’ll sit because I always do this—sit and go play, sit and go play.’ So the distraction, playing, running at large, is the reward I use to get my reliable sit.”

But beware of overconfidence, says Ian, even if you’ve done a great deal of training. “When people say, ‘Oh, my dog’s totally reliable,’ I just pull out my wallet and say, ‘Right. I have a test here, a hundred bucks.’ And as yet, no one has ever passed this test. All it involves is asking the dog to sit eight times in a row … but in weird situations. I’ll have the owner lie on their back, or have the owner out of sight. And it’s just a test of the dog’s comprehension of ‘sit.’

“So the point is, most people cannot control their dog if their back is turned and the dog is just one yard away from them. Well, what if the dog were forty yards away, but his back was turned, and he’s chasing a child or a rabbit, you see? So the problem can be shown right here. Your dog doesn’t know what ‘sit’ means if he can’t see you. So I like to take people and show them, no, your dog’s not reliable. And we can do a lot of work right here before you push the dog too far, too fast, and have him off-leash in the dog park where he’s too far away from you. Because you don’t want to set the dog up to fail. You want the quality of life, the experience for the dog, to be so much better.”

As we left the park with Dune, Ian remarked on what a special relationship each of us shares with our dogs and lamented the fact that more people don’t have the same wonderful off-leash experiences. “There’s not many people that can wander around, dog tagging behind like you with Junior or me with Dune or Hugo. We know these dogs are really totally safe around people, but we both put a lot of work into it.”

Before our two-day visit was over, Ian and I opened a couple of beers and sat down to talk about the things that brought us together—as well as some of the issues that might still separate us. We definitely share a deep affinity for dogs and the desire to train humans to be better humans to their dogs. We both want to show humans how to understand the world through a dog’s eyes, even though we have our own ways of doing things that may not be the same and may even conflict in some areas. Now that he had spent time with me and seen firsthand how I interact with dogs, Ian shared a few specific things that he wished I would do differently, especially on the Dog Whisperer show.

“You know, we may have disagreements, and there aren’t really many,” he mused. “I would like to see you slow down with some dogs, but I do understand what’s coming behind you. You know, you have a director, a producer, cameraman, they get in there, ‘Solve it, get in there, solve it! Let’s get some action.’ And you’ve got fifteen minutes. But I would just like to see, hey, take a few minutes, toss a few treats. See if you can get the dog to take a treat from your hand. And I think that would be some extra magic to show people. And because you’ve got great dog-reading skills, when the dog is upset, learn from the dog. I mean, the great things I’ve learned about dog training haven’t come from books. They came from the dogs where I royally screwed up and got into situations and thought, ‘Well, I won’t do that again.’ ”

For my part, I truly admire Ian Dunbar’s incredible range of knowledge about and skill with dogs, and I learned many things from my time with him that I will take back and assimilate into my own work. Yet there are some areas in which our personal styles are far apart. Working quietly with dogs is such a part of me that I could not try to be the outgoing, exuberant, verbal person Ian is around dogs without the dogs knowing that I was faking it. His techniques work so well for him because he is totally, 100 percent genuine; these are the methods he invented, and he accomplishes them brilliantly. They are who he is. I also believe that dogs communicate with one another using touch, so that when I give a firm—not harsh—touch in a calm-assertive and not frustrated or emotional state, I am using a very natural way of redirecting a dog’s attention. Ian, on the other hand, feels that most human hands cannot be trusted and that using touch carries too high a risk of abuse.

But all these different ideas highlight the message of this book, which is that it is crucial to have knowledge of and exposure to many different ideas, many different theories, and many different methods. You have to find one that works for you—for the person you are, for the values you hold, and for the dogs you own.

I felt as though Ian Dunbar and I accomplished something important together by opening a line of communication and showing the world that there are many options, and many possibilities, and that we both want the same thing, and that is peaceful, balanced dogs and peaceful, balanced humans.

“We have to talk to each other. Because what you and I have to teach, Cesar, is really special. When you look at the biggest foibles people have, it’s in getting along with other people. Well, that’s the skill we can teach, because we have to get along not only with another living being but with another species. I think the most important thing is talking to people who may not see it your way, and if you want to change things, that’s everything. I’ve never been one to shun someone because they don’t see it my way. They are the people I want to talk to rather than limiting my audience and preaching to the converted. It’s all about dialogue. And you know, if we take this little field of dog training, there’s an analogy for the world. The world is all different people who all see things differently.”

Before I ended my two-day visit with the Dunbars, I felt that I had to correct one important misconception. No, it wasn’t about me, my methods, or my philosophies about working with dogs. It was about Junior. I just couldn’t leave Berkeley with Ian Dunbar thinking my brilliant right-hand pit bull was slow!

A lightbulb had gone on in my head when Ian brought out the lettuce that motivated Claude and when he spoke about finding that special thing that turns your individual dog on. There’s one thing that Junior always responds to, and that’s a tennis ball. He’ll jump as high as a kangaroo, dig in the dirt like a bulldozer, dive underwater like a dolphin, and churn up dust like a racecar—all to get control of a coveted tennis ball. What if I asked Ian to do his request-lure-response-reward sequence with Junior again—except this time use the tennis ball instead of the treats?

“Well, this is a different dog today,” Ian said after working with Junior for a few minutes using my new tennis ball strategy. Junior was doing his sit-stand-downs in rapid-fire succession and in perfect form, never once taking his eye off the ball. “Yes, he’s supremo. I think the fastest dog I’ve ever seen.”

“Yes, sir,” I told him proudly. “That’s ‘Flash’ Junior.”

IAN DUNBAR’S SEVEN RULES