APPENDIX II

A Short Cut to Enjoying and Criticizing Plays, Films, and Television Shows

Six men have the power in New York to decide whether a play should live or die. They are decent and honorable men, these six. I believe implicitly that there is not one iota of malice in them, and still, if they happen to dislike a play, everyone around the theatre will make money and the dramatist will become famous.

Whose fault is it that six, good, capable men should be the sole judges, and the arbiters or the executioners in the name of 8,000,000 people, and decide what play should live or die?

This power has been given to them by the people of New York.

If anything is wrong with this system of reporting, the responsibility lies not with those who report, but with those who have relegated the power to a few to judge, to select suitable plays for them to enjoy.

How can six men know what 8,000,000 people are going to love or reject tomorrow? The temper of one man or many is mercurial, in a constant flux. No one can say with authority how the people are going to feel tomorrow.

Economic forces, the threat of war, or any national calamity, such as a depression or an inflation, can influence the temper of people so thoroughly that it can mean the complete reversal of what the majority wished or clamored for twenty-four hours earlier.

The public is lazy and negligent. They seem to say “Let someone else tell us what we should wear, do, eat, see, or hear. Our sole purpose in life is to make a living. Let others who know better tell us the rest.”

Such irresponsible behavior means abdicating the power of thinking, of reasoning, of selecting, of being a man. To forage like an animal, to connive, to steal, even kill for food, is an inborn atavistic instinct of the herd to live, but it is not the sole aim of the man who fought his way up from the primeval ooze, to be master over all that lives on this earth.

To think is to be alive.

Not to think is to be dead.

This section will help the man who has the strength and who wishes to arrogate for himself his birthright, to select and enjoy a play, movie, or TV show without anyone telling him first whether it fits his taste or not.

It is a grand feeling to be grown up, to be mature, and to think for oneself at last.

The undying popularity of baseball springs from the spectators’ intimate knowledge of the game. By knowing the three dimensions of a human being and the structure of a play, the audience too can follow the intricate pattern with the greatest ease, and such intimacy will enhance the appetite of the public to go more often to the theatre, not only to enjoy, but to match wits with the professional reviewers. The influence of the reviewers would not necessarily be diminished by the audience’s understanding of a play. They could remain as impressive as before, only the power of being the law and the executioner of the theatre would be taken away from them forever.

THE SHORT CUT

Curiosity is man’s inherent characteristic. If you happen to pass two quarreling people on the street—if you are part of the majority—you would like to know what the quarrel is about.

It is important for you to find out as soon as the play starts what the author intends to say to you.

There are two main forces that struggle against each other on the stage, the Protagonist and the Antagonist.

If you remember this, you shall understand the intricacies, the structure of any kind of play, let it be a sordid drama, comedy, or farce. Even fairy tales conform to this rule.

The Protagonist sooner or later starts the conflict. If he starts late, then there is one strike against the play. People don’t go to the theatre to hear polite conversation. They expect suspense and conflict.

How do you recognize the Protagonist?

He starts the conflict.

For whatever reason one holds a grudge, suspicion, legal or illegal claim against another, if he is willing to prosecute him to the limit, he is the Protagonist.

The aggressor is always the Protagonist.

If the Protagonist forgets his grouch, suspicion, or whatever he has against his adversary, the play starts to die.

Why does the audience always demand conflict in the theatre?

Because no human being will expose himself without conflict. No character can show his inner turmoil, contradiction, vacillation, self-doubt, hate, or love to the audience without attacking or defending himself.

Every one of us has a thousand faces.

Which is the real one?

Without conflict we’ll never find out.

Since we wish to find out the motivation, the nature of the Protagonist, he should be provoked by the Antagonist’s refusal of his demands.

The Antagonist is the other force, besides the Protagonist, who sparks the conflict; he is willing to fight, struggle, to connive, to undermine, to divert the attention of the Protagonist.

Without the Protagonist the Antagonist has no reason to exist.

Neither the Protagonist nor the Antagonist can exist without each other.

No shadow can exist without light, and vice-versa.

Life has no meaning without struggle; struggle is the essence, the foundation, the means of existence.

Every action creates a counter action. It should be a chain reaction which goes on interminably in an ascending scale.

All conflict in all plays (as has been true in the past and will be true in the future) is for or against the status quo.

Any small squabble, insult, little or big war (and this includes the two World Wars) started for or against the status quo.

The Protagonist is always against the Antagonist. This is the essence, the bone structure of all writing.

Their struggle takes many forms—simple or complicated, symbolic or real. But whatever form they take, don’t forget the conflict is between the Protagonist and the Antagonist, and must go on if the play is to live.

The play, any play, is supposed to be the mirror of life.

Struggle is the essence of life.

If you know the rules of the game, you will enjoy yourselves better than just waiting in the theatre to be stirred and entertained.

You are watching two people fight in the arena; one is the Protagonist, the other is the Antagonist.

If the Protagonist is so strong, so overwhelming that there is no doubt in your mind who is going to win, the result will be boredom.

The combatants should be evenly matched.

The Antagonist should not be submissive either, or so frightened that you are sure he will be smashed, destroyed even before the fight is started. The effect will be the same as before. You will lose interest.

The evenly matched combatants almost immediately create suspense.

The play, movie, or TV show must concern itself with the problems of man: love, hate, avarice, suspicion, ambition, or any other of the myriad fears that beset all mortals.

Man is a complex entity. He goes to the theatre not only for entertainment, but to understand himself. Since all human emotion is universal, he will compare his with that of others. Whichever problem the author chooses to write about, he must dig deep, to the very root of struggle, to be true.

Here was a man who was jealous of his wife.

It was obvious that he was jealous, but it was not so obvious why he was jealous.

Did she take him for granted? No.

Did she feel superior and treat him as a poor relation? No.

Did she flirt? No.

Was she unfaithful to him? Positively not.

On top of all this, she was kind, softspoken, and in love with her husband.

Then why, in heaven’s name, was he jealous?

I quote: “I never finished elementary school and I am making money by the carload, while you with your fancy degrees can’t get more from that crummy two-bit library job than seventy bucks a week.”

She didn’t answer his taunting, sarcastic, dirty digs. He never made her forget that he was supposed to be an ignoramus, a man who never read a book and was proud of it, yet could get a woman like her to crawl after him.

They had three children, and through the years he made her disillusioned, bitter, even desperate. She devoutly wished for a divorce or widowhood as preferable to continuing to live with this ruthless, jealous man.

He was jealous of her intellectual integrity. He was jealous not of men, but of seeing her read a book. Any book was his adversary.

He was relentless. He constantly tried to undermine her importance and prove to her, and to himself of course, that higher learning was the bunk. A clever man didn’t need school or books to succeed. He wished to prove his superiority not only above her, but above schools.

All Protagonists are, by sheer necessity, relentless—for whatever reasons—and the Antagonists, if they intend to stay alive, must fight back. The Antagonists perhaps fumble at first, but slowly, under the ruthless onslaughts of the Protagonists, will protest, reject, refuse, and at the end revolt.

Every human being fights constantly for his or her superiority.

The importance of being important is the equivalent of self-preservation.

What else should we know about the Protagonist? Why is he the Protagonist?

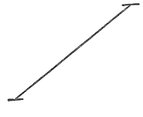

If you really want to enjoy the play and know how to criticize it, study the following diagram:

The above line tells you that every play, movie, or TV play should be built on slowly rising conflict.

Slowly rising means without interruption, moving higher and higher, like 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 0.

The conflict starts at 1, and proceeds in ascending scale up to 0, which is the end of the play.

Now, if the conflict bogs down, at let us say 1 or 4, or any other number, the play will be static.

Staticness is the deadly disease of creative writing.

If the play is going to jump, let us say from 3 to 7, or 5 to 8, or any other span, it will create an unhealthy reaction. The play has lost the touch of reality, has left logic, the right kind of motivation, behind. This is the cause of the jumping conflict.

The slowly rising conflict is the answer for a healthy, wellconstructed play.

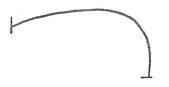

Let me illustrate the static conflict:

Staticness by its own weight sinks lower and lower to the vanishing point, where the audience loses interest and doesn’t give a hoot about what is going to happen to the people in the play.

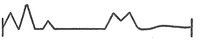

A jumping conflict might look like this:

It is erratic.

Mood and logic change so quickly, the conflict loses all semblance of reality.

If you keep in mind that the two main forces in every dramatic composition are the oft-repeated Protagonist and Antagonist, cumbersome explanations will not be necessary to understand any play, movie, or TV drama.

Every Protagonist forces the conflict throughout the play. He always knows what he wants. Iago in Othello, revenge; Macbeth, ambition; and Tartuffe, lust. Whatever the Protagonist wants, he must want it so badly that he will destroy or be destroyed in the attempt to get it. But no real Protagonist will start a conflict because of a whim. Necessity drives him.

Once more, please, dear reader, remember that necessity drives the Protagonist on and on.

If there is no unbreakable bond between the two main forces, they are likely to walk out on each other. (This is a beautiful contradiction. The seemingly unbreakable bond should break by death, or a dramatic change in a situation of a character at the end of the play.)

The unbreakable bond is created by great love, great hate, hurt ego, revenge, or any other emotion you can think of, if you put before the emotion the word “great.” It must be really great.

Only a great uncontrollable drive, a compulsive force, can carry the Protagonist through a three-act play. You never saw a good play in which the Protagonist remained complacent.

Conflict is the heartbeat of every play. Conflict is the oxygen, the food for a play to thrive on. Without conflict there is no play, and in reality there would be no life on earth either.

If conflict doesn’t grow in intensity, the play will drag and become repetitious. You will find the play falling apart.

SUMMARY

1) How does one recognize a three-dimensional character? Very simply. Through conflict.

2) Let me repeat. Every man has a thousand faces. Only through conflict can layer after layer be peeled off, until you find the real man or woman crouching behind the façade.

3) The moment the play opens, find the Protagonist . It is easy to recognize him. He starts the conflict.

4) The Antagonist stands right there, at the opposite corner.

5) The perfect opening for a play is to start with a crisis, which grows in intensity and explodes into a climax.

6) Static Conflict, the deadly sickness of all plays, occurs if the characters are weighted down with repetitious dialogue.

7) Jumping Conflict is the sign of lack of motivation. Without motivation characters become straw men.

8) If there is no strong bond between the characters, there is no good reason to fight. They simply can walk out from the action, and the play ends before it starts.

9) The rest of the characters in the play will side with one or the other of the combatants.

A play is really a mirror; whoever looks into it will be reflected back, not as he looks, or as others see him, but as he sees himself at the moment.

THIS IS ALL