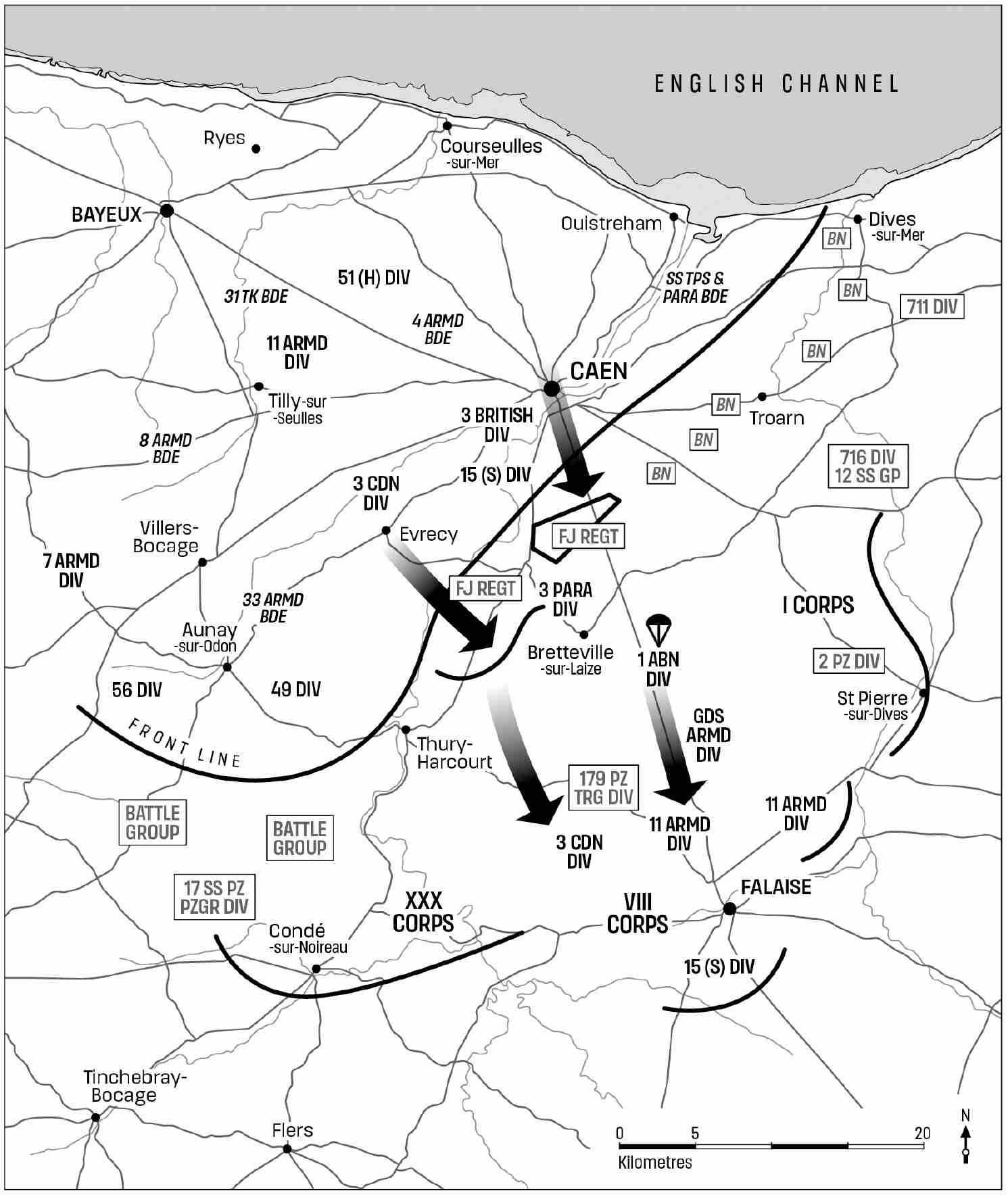

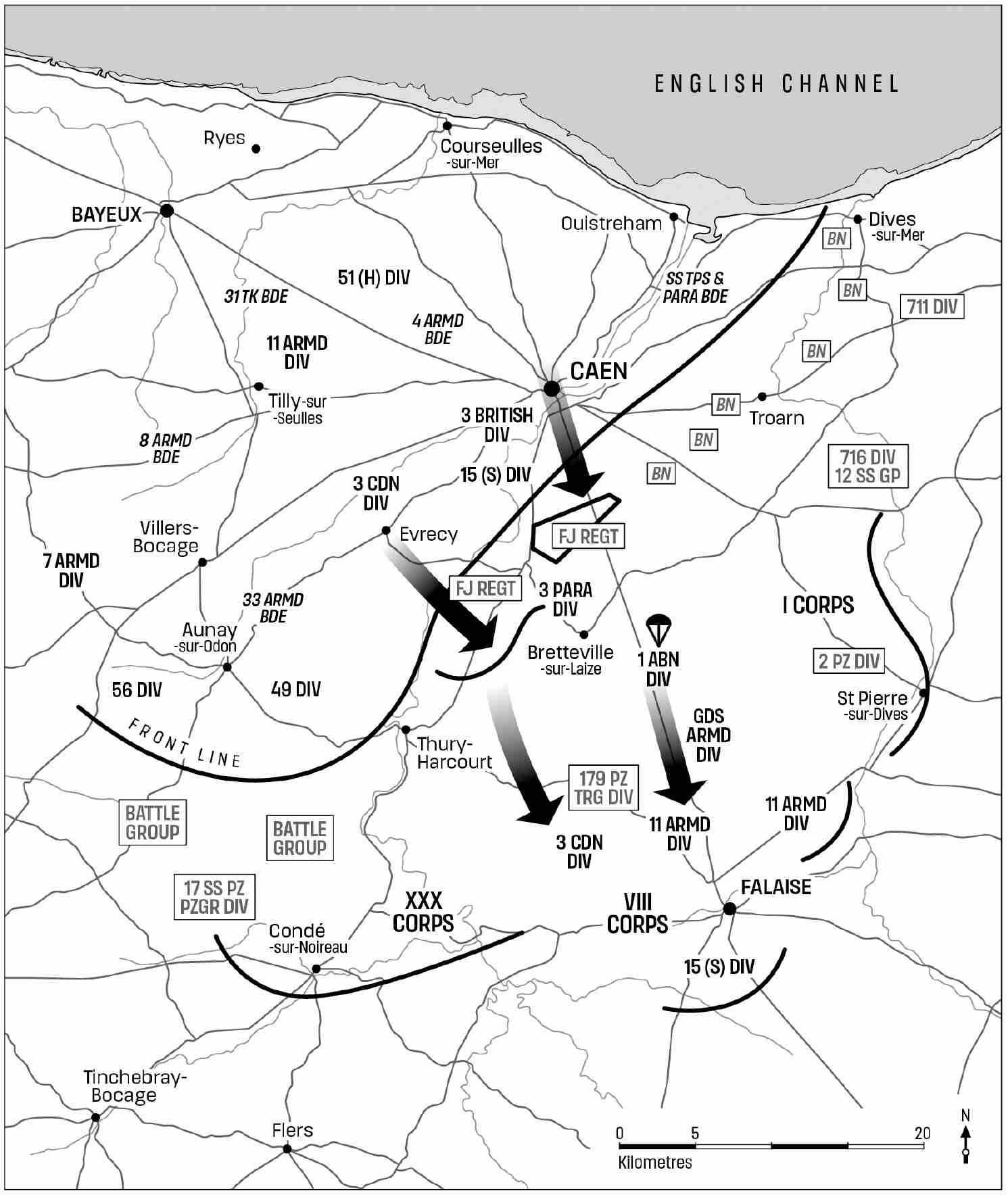

Map 2: The scenario envisaged in Exercise Wake. (Source: TNA WO 285/1)

The first alterations to the airborne element of the COSSAC plan were made soon after Eisenhower and Montgomery were appointed as Supreme Commander and Commander-in-Chief of 21st Army Group in late 1943 and early 1944 respectively. More senior than Morgan, they were able to make substantial changes immediately. A US airborne division was added to land in the Cotentin to support the US landings on Utah Beach after Montgomery had argued that the landings were on too narrow a front. Montgomery also rejected the proposal to drop a British airborne division on Caen – the US Air Force Historical Study describes him as having ‘never cared’ for it – and switched the British airborne landings to east of Caen around the Orne.1

Work also started to integrate the British and American airborne forces. On 10 January 1944 a joint conference was held between 38 Group and IX Troop Carrier Command to discuss equipment and common techniques.2 It was also attended by representatives from HQ Airborne Forces and the senior staff officers of both 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions. The conference was particularly important as it was increasingly likely that British or American aircraft would be used to land either country’s airborne forces and there would be a need for standardised procedures. Much of the details concerned technical aspects such as roller conveyors for dropping supplies and static cables for parachuting. It also recommended the establishment of a conference room with direct telephone lines to 38 Group, IX Troop Carrier Command, US Airborne HQ – which did not exist until much later in August – and British HQ Airborne Troops to enable representatives to hold detailed planning conferences, and to function as a command post during operations. This later became CATOR (Combined Airborne Transport Operations Room), or TCCP (Troop Carrier Command Post), and was the first tentative step towards centralised coordination of Allied airborne forces.

On 25 January 1944 Browning set down his thoughts regarding the employment of airborne forces during Operation Overlord in HQ Airborne Troops Directive No. 2. The directive, distributed to Montgomery’s Chief of Staff Major General De Guingand, Leigh-Mallory’s Senior Staff Officer Air Vice Marshal Wigglesworth and Air Vice Marshal Leslie Hollinghurst, the Air Officer Commanding 38 Group, was an attempt to establish a firm policy as to how airborne forces should be used in combination with amphibious landings. Browning estimated that a division could be prepared for an unforeseen operation in 48 hours if photographs and briefing material were available. This timeframe would be shown to be wildly optimistic – Market Garden took seven days from inception to take-off and Browning himself would threaten to resign over a shortage of maps when an operation was planned at only several days’ notice.

An initial two airborne divisions would be used in the first wave on D-Day and one division would be held in readiness to be flown in if the advance from the beaches had slowed down or in the event of an emergency. The ‘emergency division’ would only be able to take on simple tasks due to the lack of time that would be available for planning and the quick turnaround of aircraft returning from the first landings. Another division would be available for longer-term tasks, pre-briefed and with reconnaissance photographs available. Once the fourth division became available the third division would stand down. Thus Browning recognised as early as January 1944 that divisions could not be held at high readiness indefinitely. Despite this, 1st Airborne Division did not get to stand down between early June and mid-September and was stood to more times than it should have been because 6th Airborne Division was not withdrawn in time. In effect it fulfilled the roles of the notional ‘third’ and ‘fourth’ airborne divisions, those of both the reinforcement and long-term strategic roles. The dual role that it was allocated complicated planning for its employment.

Whilst planning was continuing in Europe doctrine was also being developed at a considerable distance in Washington. Independently of Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) the US Army Air Force Headquarters developed a plan that expanded on Arnold’s previous idea for a large-scale airborne operation deep in France. The plan, written by Brigadier-General Frederick Evans, the commander of I Troop Carrier Command, and Colonel Bruce Bidwell of the Operations Plans Division, was approved by Marshall on 7 February. It proposed a combined drop of two divisions between Evreux and Dreux on the night of D-Day. These divisions would capture four large airfields to enable two additional divisions to be airlifted in by D+1.3 Evans and Bidwell flew to Britain carrying a letter from Marshall stating – somewhat paradoxically – that although he did not wish to exert ‘undue pressure’, he expressed strong ‘personal support’ for the plan, and criticised previous airborne planning as ‘piecemeal’, ‘indecisive’ and ‘narrowly conceived’. Expressing ‘strong personal support’ could hardly be described as not exerting ‘undue pressure’, and this suggests the pressure that Eisenhower was under from his mentor.

In March the Air Staff at SHAEF were asked to study ‘the employment of Airborne Forces in relation to a given plan’, which was almost certainly Marshall and Arnold’s proposal.4 The plan envisaged a ‘Force A’ of six parachute brigades being dropped in the rear of the assault beaches as late as possible before dark on D-1, a ‘Force B’ of thirteen parachute ‘detachments’ to be landed further inland and a ‘Force C’ of an additional airborne division to be landed on D-Day as early as turnaround permitted. The Air Staff were asked to also consider the possibility of all three forces being dropped at the same time. They assessed that this would require minimum troop carrier airfields to launch and the production of 5,300 briefing models and there would be significant issues with briefing such a large force and designating routes. Take-off would also cause considerable problems. It did not take the Air Staff long to conclude that the proposed plan was completely impractical.

The plan from Washington was unsurprisingly rejected by Eisenhower on the grounds that the airborne forces would not be mobile enough once on the ground and that plans to supply them by air would not be feasible. Eisenhower saw airborne forces as aiding a breakthrough rather than being the breakthrough themselves. These fears were certainly well founded, demonstrated by the rate of progress made by ground forces during the Battle of Normandy and the vulnerability of airborne forces far behind enemy lines in Market Garden.

Meanwhile manpower was becoming a problem that would affect airborne planning. As early as 11 March – just under three months before D-Day – it was found that it would be difficult to provide airborne-trained reinforcements once operations began. Steele at the War Office wrote to 21st Army Group, Home Forces and overseas commands suggesting that the situation was made worse by the use of airborne-trained reinforcements once airborne units were in action on the ground, as airborne divisions were designed for short operations and were not suited for a prolonged ground role. Steele therefore suggested that once airborne units had landed they could be made up with reinforcements from the normal infantry pool and could be reorganised once out of the line. Whether this would have been feasible given the airborne formations’ esprit de corps is questionable, but that it was being discussed even before D-Day suggests that manpower shortages would have a limiting effect on airborne operations.

Meanwhile the troop-carrier forces were making progress in standardising procedures and equipment. On 28 March 38 Group published a Standard Operating Procedure for Paratroop and Glider Operations, to take effect from 7 April.5 It covered staff and airfield procedures, loading, marshalling and despatching and aircraft and pathfinder procedures. It also laid out the various responsibilities of air and airborne commanders and headquarters and a standard agenda for co-ordinating conferences and standard forms. 38 Group would organise the commanders conference jointly with airborne forces, organise the co-ordinating conference and select drop zones and landing zones jointly. The Airborne Commander would jointly organise the commanders conference, be represented at the co-ordinating conference and jointly select drop zones and landing zones. An Appendix to the Procedures outlining the structure of Allied Air and Airborne Organisation showed a ‘British and US Combined Op. HQ’, a headquarters that did not exist in March 1944, and a ‘HQ US Airborne Troops’, another non-existent organisation.

HQ Airborne Troops Operation Instruction No. 1 was issued on 22 April by Browning’s Brigadier General Staff Gordon Walch and outlined the procedures for launching airborne operations during Operation Overlord. 21st Army Group would ultimately decide on the operation to be carried out by airborne troops and would allocate aircraft in conjunction with Allied Expeditionary Air Forces (AEAF). HQ Airborne Troops would retain control of airborne formations until they took off and after landing they would come under the command of formations already in theatre. At this stage there was clearly no intention for a corps-level airborne command to take the field and the role of HQ Airborne Troops role was still limited to an administrative function in mounting operations.

As there was limited accommodation and briefing facilities in camps attached to RAF airfields it would not be possible to move troops taking part in follow-up operations to airfields until the preceding troops had taken off. This affected the ability to launch airborne operations in quick succession. This was also dependent on the availability of transport aircraft and the level of losses experienced in the initial assault.

Maps would be a critical factor in launching airborne forces. These would only be drawn from the map depot at Newbury in time for them to be issued immediately before an operation. Although this is perhaps understandable given the broad geographical area in which airborne formations could be expected to operate, it inevitably hampered the ability of planners to prepare adequately for operations. Later in the campaign Browning would make a stand over the issue of map supply.

One of the more unlikely sections of the Instruction warned of the possibility of German parachutists taking part in ‘suicide raids’ on airfields containing airborne troops preparing for operations. Commandants of transit camps were ordered to prepare a defensive scheme, including digging slit trenches. This warning does seem rather fanciful given the state of the Luftwaffe and the German airborne forces by 1944 and may have been more about getting the airborne troops into the habit of digging in.

A HQ Airborne Troops movement order issued by Walch on 4 May dealt with the movement of airborne troops to airfields prior to operations. 1st Airborne Division could not move to the transport airfields until after 6th Airborne Division had taken off for D-Day, meaning that a follow-up operation could not be mounted until several days afterwards due to the lack of accommodation and the turnaround time required for the transport aircraft. Therefore the division was to be prepared to take part in an operation at 72 hours’ notice to remain in action for 14 days afterwards. This timescale would seemingly change for every operation.

The next day, on 5 May, Browning issued a memo to 21st Army Group G (Ops) concerning the weather conditions required to mount airborne operations. These included the visibility, wind speed, cloud base and moon conditions under which pilots – of powered aircraft and gliders – could operate. These also covered the conditions at airfields, en route and around the drop zones. This clearly reinforces that at this stage in the planning for Overlord airborne operations would be commanded through the usual command structures rather than by a dedicated airborne corps-level headquarters.

Although Montgomery is often cited in the historiography of the Normandy campaign and the commander of the British Second Army Lieutenant General Sir Miles Dempsey is often viewed as a relatively passive figure, records suggest that Dempsey played a much hands-on role in formulating airborne theory and developing operations than this reputation might suggest. He also demonstrated more clarity of thought regarding airborne operations than his superiors or his peers. An undated memo produced by Dempsey several months before D-Day and circulated to his corps commanders Crocker, O’Connor, Ritchie and Bucknall, as well as Browning, suggested that British airborne forces could be used to assist the advance of XXX Corps and I Corps from their D-Day objectives, and that they could well be used in conjunction with VIII and XII Corps who were to land shortly after D-Day and had been given exploitation roles.6 In another memo dated 21 March 1944 Dempsey cited the lack of momentum after the Anzio landings as a scenario in which airborne forces could be used in place of further seaborne landings to prevent the Allied advance becoming bogged down:

The objective of the airborne forces must be strictly related in time and space to the main body, and the commander must be ready to employ his maximum force in conjunction with his air-flank operation. Properly employed, such an operation will be of the greatest assistance to the main body in breaking out . . . the available airborne reserve should be of the utmost help in keeping the operation fluid.

Dempsey’s planning notes prepared prior to D-Day also suggest that he discussed airborne operations with his corps commanders on several occasions. He also mentioned airborne forces in depth during his briefing at Montgomery’s Exercise Thunderclap on 15 May 1944:

I have already told you how valuable I think 1 Airborne Div may be in assisting the advance of Second Army – being landed behind the German lines in conjunction with a full-scale attack by the main force … It is important, therefore, that you should know exactly how it should be used, and the machinery necessary to plan and organise the operation.

The machinery which Dempsey referred to had arisen largely from lessons learnt during a pre-invasion planning exercise. The corps commander and several of his staff officers would be at Second Army Headquarters and as soon as a decision was made to employ 1st Airborne Division, Browning, his staff officers and those from 1st Airborne Division would join the relevant Corps HQ to plan the operation. 1st Airborne Division would be given warning orders so that it would have 48 hours’ notice of the operation. The airborne officers would then return to England to issue orders to the division. This was a much more streamlined command structure than would eventually be used in Market Garden and employed Browning as an advisor rather than as an ad-hoc corps commander.

Perhaps one of the most insightful planning exercises before D-Day, and one of the least known, was Exercise Wake. Prior to D-Day Dempsey ordered the commander of VIII Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Richard O’Connor, to hold a staff exercise to study the employment of airborne forces in assisting with a breakout from the bridgehead. VIII Corps was not part of the initial assault forces on D-Day and its units were due to land in the days after the initial landings. Therefore O’Connor’s corps had a role to firstly reinforce the assault formations and secondly to attack and expand the bridgehead.

Map 2: The scenario envisaged in Exercise Wake. (Source: TNA WO 285/1)

Exercise Wake took place on 8 May 1944 and was attended by the Commander, Chief of Staff, Commander Royal Artillery, Assistant Quartermaster General and Officer Commanding Royal Signals from 1st Airborne Division; Lieutenant-Colonel Wright and Major Beasely-Thompson from HQ Airborne Troops; and the Brigadier General Staff, Commander Corps Royal Artillery, Deputy Assistant Adjutant and Quartermaster General, Chief Signals Officer and Commander Army Group Royal Engineers of VIII Corps.

On 13 May 1944 O’Connor – who was not present at the exercise – submitted an outline plan to Dempsey based on the results. The objective of Wake was to dominate the Falaise area, particularly its key road junctions. The plan was for an advance commanded by VIII Corps with 3rd Canadian Division under command, using 1st Airborne Division to break out from the Overlord bridgehead through the positions of I Corps and then strike out along the road from Caen to Falaise.

O’Connor felt that this would be a feasible but slow operation and would take between a week and 10 days to complete. The advance by VIII Corps was to be led by three infantry divisions. It would start with an assault crossing across the River Orne south of Caen on the night of D+13/14. As darkness fell on D+13 the 15th Scottish Division was to move forward to the western banks of the River Orne, bringing up enough bridging materials to build two bridges. At last light the next evening on D+14 the assault troops of 3rd Canadian Division were to assault across the Orne and capture a bridgehead big enough to facilitate a bridging operation at Amaye. The Canadians would be supported by over 150 guns, including Royal Artillery units from Corps and Army Group Royal Artillery. At the same time 15th Scottish Division was to capture enemy positions around Bourguébus supported by over 200 guns. Meanwhile I Corps would carry out a diversionary attack from its positions from east of the Orne.

After last light on D+15 1st Airborne Division was to land and take up a defensive position around Cauvicourt, Bretteville-le-Rabet and Urville with the intention of disrupting the enemy’s communications. It was predicted that the airborne troops would be swiftly attacked by 2nd Panzer Division and would therefore need to make all possible use of natural anti-tank defences. Given the Airborne Division’s relatively light organic artillery, four batteries of 155mm guns were to be on call to provide support from the beachhead. The plan for the airborne landings is interesting in several respects, firstly that they were being dropped only after the advance had already started and relatively close to the front line, and secondly a strong German armoured counter-attack was assumed but not deemed to be serious enough to prejudice the operation.

Also on the night of D+15 the 11th Armoured Division was to be ready to pass through or around 15th Scottish Division as soon as circumstances permitted the next day on D+16. They would reconnoitre on both flanks of 15th Scottish to establish the most suitable side on which to advance. At first light 3rd Canadian Division would advance to and dominate the area of Bretteville-sur-Laize, Fresney le Vieux and Point 183. 15th Scottish Division were to advance to the area Cramesnil-la-Bruyere, Cintheaux and Cuilly. The plan allowed flexibility for 11th Armoured Division to use the most suitable axis of advance, an option that would not be available to their counterparts from the Guards Armoured Division in September.

By the afternoon of D+16 the 11th Armoured Division would have passed through the positions of 15th Scottish Division and after linking up with the Airborne Division would continue exploiting south towards Falaise. 15th Scottish and 3rd Canadian Divisions would follow up and contact 1st British Airborne Division around Cintheaux, Cauvicourt and Bretteville sur Laize. The Airborne Division would then be evacuated from the battle area. It was hoped that I and XXX Corps would advance along with VIII Corps. The airborne landings were therefore clearly not seen as the tip of the spear but as a means of assisting the ‘break in’ by landing close behind the German lines. The armoured advance was therefore not a do-or-die dash to relieve the airborne forces but instead would use them as a springboard.

In his outline report arising from Exercise Wake O’Connor suggested that airborne forces could be employed in either a tactical role, assisting the ground forces in overcoming the defences in front of them in the initial stages of a battle, or strategically. O’Connor described this more strategic possibility as ‘. . . dropped much further into enemy country to tie up with, and to facilitate, the rapid advance of armour’. This choice between tactical and strategic use of airborne forces would dog airborne planning for months to come.

All of the British and Canadian corps commanders were sent the results of Exercise Wake and were also provided with a map trace showing the available landing zones in the Second Army area. The results of Exercise Wake also summarised, somewhat presciently, some of the key issues facing the employment of airborne forces:

Should the landing be successful, it seems that the Airborne Div may be employed too late, as by then the battle will be half over. These two objections can be avoided by dropping the Airborne Div in conjunction with the initial attack. But it will mean accepting the risk of a longer delay in effecting a junction with the Airborne Div.

The exercise also led to a number of practical recommendations. As soon as a joint operation involving airborne forces was ordered, a planning team from 1st Airborne Division would go to the relevant corps headquarters. This planning team would include the divisional commander, chief of staff and an RAF representative. It was estimated that the airborne planning team would require four days to mount an operation, and that once on the ground the division would come under the orders of the corps that would be linking up with them. Interestingly this plan foresaw no role at all for Browning.

It has been suggested by that the broad thrust of Exercise Wake towards Falaise is an indication that Dempsey intended to break out on the eastern flank of the Caen bridgehead.7 It is extremely unlikely that any of the commanders involved foresaw that the exact scenario predicted for the start of Wake would in fact transpire almost two weeks after D-Day. Exercise Wake was exactly that – an exercise, and one to develop procedures and policy rather than concrete plans. The lessons learnt could – and should – have been applied to any similar operation launched from anywhere within the bridgehead. But by ordering the exercise it does suggest that Dempsey was thinking very seriously about using the 1st Airborne Division to aid an advance after the initial landings.

Wake also drew out some valuable lessons for planning airborne operations. Finer details discussed included tactical recognition, wireless connections and the exchange of liaison officers. A signals exercise between the Airborne Division and VIII Corps was also planned, and significant attention was also given to how the relevant artillery commanders would co-ordinate efforts to support the Airborne Division. Wake envisaged the Airborne Division to land a relatively short distance behind enemy lines, after the ground attack had already started and within range of corps-level artillery support. These were policies that were increasingly ignored as the campaign wore on.

There is no evidence that the lessons from Exercise Wake were shared with anyone beyond Dempsey and his corps commanders, nor that it was shared with Montgomery or anyone at 21st Army Group. The points arising were of importance to any headquarters that might have been called upon to mount airborne operations. But these lessons were not shared and airborne operations would be planned by headquarters and staffs who did not have the advantage of having exercised similar scenarios, or exercised with the Airborne Division’s headquarters.

Dempsey was clearly influenced by the findings of Wake during his Thunderclap briefing on 15 May:

We must concentrate all our efforts during the early weeks of the invasion to ensure that we do not get pinned down. We must retain our ability to keep the operation fluid. We must hold 1 Airborne Div in reserve until it is clear that we may be unable to break out of the ring without their assistance. Then we must use them in conjunction with the main attack to make sure that we do break out.

So I say that the correct use of 1 Airborne Div in the Exercise which 8 Corps carried out was to assist in Phase I or Phase II – to be used in conjunction either with the initial or with the second infantry attacks. If they succeed, we will have broken through the ring and the armour can then play its part.

Dempsey also stressed that a junction between the main force and the airborne force should be effected within 24 hours. He suggested that if the proposed operation was a risky one – water crossings were specifically referenced – then the airborne forces should not be dropped straight away, and their use should be held back until the progress of the battle could be assessed. During Exercise Wake VIII Corps did not land 1st Airborne Division until the assaulting infantry division had broken through the German front lines and had allowed the armoured division the best possible chance of relieving them, a decision that Dempsey approved of.

A key lesson from the planning of the airborne operations that took place on D-Day compared to the subsequent campaign is that set-piece operations offered ample opportunities for training, planning and preparing equipment. A report into the British airborne effort in Normandy described numerous combined airborne exercises held during February, March and April 1944, at battalion, brigade and then divisional level.8 These were held over terrain like that which would be found in Normandy and included day and night landings and detailed rehearsals for operations such as those at Pegasus Bridge and the Merville Battery. Another unique feature of the airborne operations in Normandy was that most troop carrier aircraft were grounded for three weeks prior to Overlord, which ensured almost 100 per cent availability – a level which would never be achieved again in North West Europe. In this and many other respects comparing D-Day with Market Garden is to compare football matches that were played with a different number of players on each team.

It is not proposed to conduct a detailed examination of the airborne landings in Normandy here – a significant historiography exists, and that is not the purpose of this book. However, it is of interest that very few commanders or planners were able to draw detailed conclusions from the airborne landings in Normandy before Market Garden took place. 6th Airborne Division, for example, was still in the field until late August, only weeks before Arnhem. However, an undated and uncredited report found in the papers of Air Vice Marshal Hollinghurst did analyse the ‘British Airborne Effort in Operation Neptune by 38 and 46 Groups’.9 It points out that 6th Airborne Division’s planning was overseen by Crocker’s I Corps. It concluded that the landings had confirmed ‘high hopes’ for airborne forces and that there would inevitably be a ‘certain proportion’ of failure, particularly in night parachute dropping, and that inevitably a margin of error must remain and be allowed for. It suggests that airborne plans should not rely overly on precision in time or space and that no one unit’s success should be vital to the whole operation. It also concluded that the air commander could never guarantee complete delivery to the army commander. The report also concluded, however, that the experiences of Operation Neptune would not necessarily produce a set method for the future as the situation at the start of the landings was more or less static, giving time for planning and use of surprise. It was stressed that similar conditions were unlikely to recur, and that future airborne planning would have to be to a different pattern. This would prove to be more accurate than the author perhaps realised at the time.

1st Airborne Division had returned to the UK in late 1943 and early 1944 as something of a loose administrative headquarters whose brigades had fought relatively independently. Its commander, Major General Eric Down, was a very experienced airborne officer whose replacement in early 1944 has been described as ‘strange, if not perverse’.10 Down was sent to India to command a newly-raised airborne division, even though it was not due to become operational until late 1944, and was still in Britain on other duties until after D-Day. It is likely that Down, with his airborne experience, would have used the planning period differently to Urquhart, who although a very experienced commander lacked airborne experience and was also a Montgomery protégé and therefore unlikely to rock the boat. Even Urquhart himself acknowledged that he had been given a divisional command earlier than he had expected.11 Buckingham has suggested that the assumption that the division was highly trained is misleading, although Urquhart had an unusual challenge in that he had to command a division that was scattered around the East Midlands.12

Urquhart reflected long after the war that many of the personnel in his division were not trained: ‘These chaps, the parachute battalions, had just come back from North Africa. They were wonderful individual material but they were not trained.’13 Even when interviewed decades after the end of the war he was reluctant to be quoted as saying this, but equated the situation with 51st Highland Division, which had performed admirably in North Africa but experienced problems in Normandy.

On the eve of D-Day the Allied forces had made valuable strides in integrating their airborne effort, particularly around equipment and troop-carrier aircraft. Much of the groundwork for the campaign had already been put in place, including the mechanisms for launching operations. Dempsey also appears as a much more prominent figure than he has previously. However, the early signs of problems can be seen. Eisenhower had had to fend off unhelpful interest from Washington, and Browning’s position was, even before D-Day, unclear and ill-defined. It would only become clear how much of a problem this would be when the Allies attempted to integrate the command of their airborne forces even more closely.