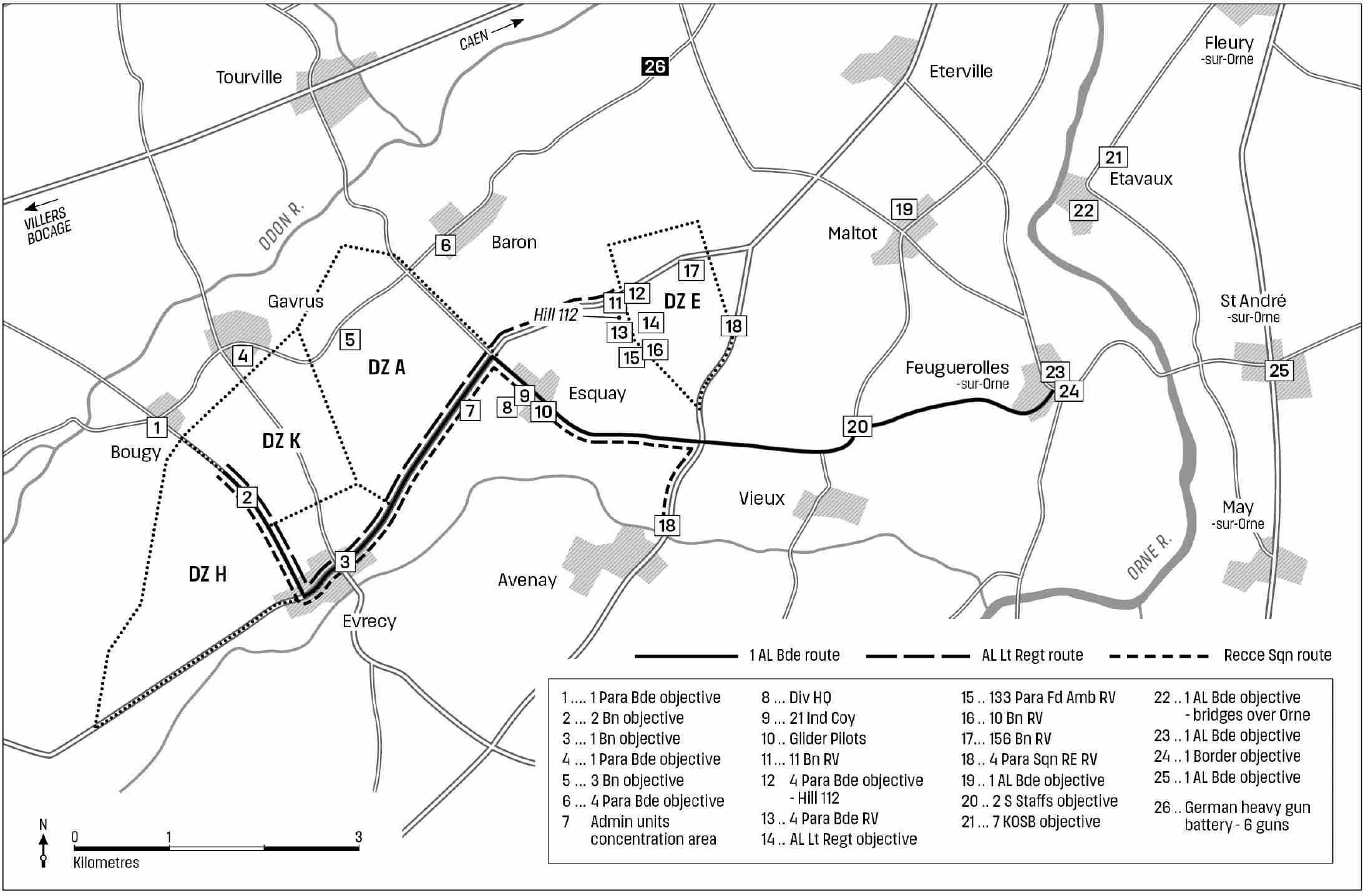

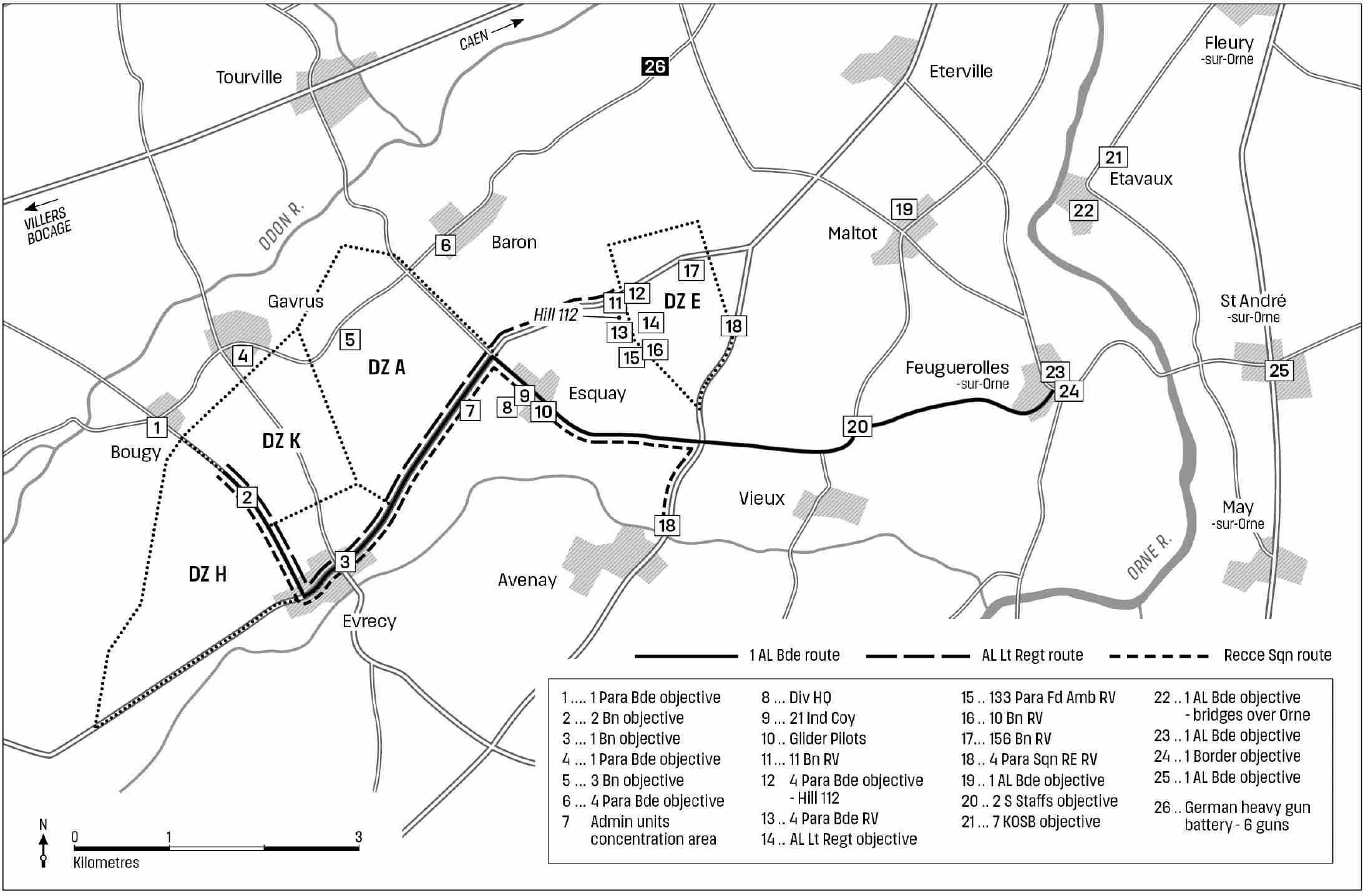

Map 5: 1st Airborne Division drop zones, routes and objectives for Wild Oats. (Source: TNA WO 171/392, TNA WO 171/592 and TNA WO 171/594)

Once the Allied foothold in France became more secure, and Tuxedo and Wastage were not called upon, the thoughts of commanders and planners turned to some of the more offensive and expansive ideas that had been considered before D-Day. The result, Operation Wild Oats, was possibly the most controversial airborne operation planned during the early part of the Normandy campaign. Equally, it has also become one of the most widely misunderstood.

The XXX Corps plan for the Normandy landings was to use 7th Armoured Division to break out of the beachhead on D+4. Despite Dempsey and Montgomery’s policy of using ‘air hooks’ in the breakout from the beachhead, there is no evidence that XXX Corps had given any thought to working with airborne troops after the initial landings. The findings of Exercise Wake suggest that 1st Airborne Division had been allocated to operate with VIII Corps which had been given a follow-up role during the breakout phase. As late as 2 June Wild Oats was being considered by 1st Airborne Division and specifically in the context of operating with O’Connor’s VIII Corps. Indeed, as late as 29 May the code name of Exercise Wake was being used interchangeably for Wild Oats.

Considering that HQ Airborne Forces was not an operational headquarters at this point in the campaign Browning was keeping a tight rein on the planning of airborne operations after D-Day. On 24 May he messaged Urquhart:

No further task has yet been received for your Division, which can be planned in detail on the ground. You are, however, already aware of the other most probable role in which your Division may be used, i.e. to assist in the ‘break-out’ from the beach-head, and you will continue to give this problem your attention. Should you consider it necessary you may inform Brigade and unit comds and 2nd grade staff officers that this is a possible task, so as to widen the scope of study given to it.

You are already in possession of traces giving possible LZ areas, and these are also held by HQ Second Army.1

This certainly fits with analyses that Browning was ensuring that he was the chief British airborne advisor, to the extent of keeping Urquhart away from meetings that his counterpart American divisional commanders would attend. This is in contrast with how Gale had planned directly with Crocker prior to D-Day, with Browning playing a minimal role.

Meanwhile, an undated memo that originated from HQ Airborne Troops suggested that 1st Airborne Division could have been landed in a location that was referred to as ‘Area J’ to facilitate the advance of 11th Armoured Division around D+14. As that division was part of VIII Corps this would again reinforce the conclusion that the division was being held in readiness to work in conjunction with that corps.

On 28 May HQ Airborne Troops signalled 1st Airborne Division and 38 Group RAF outlining four possible operations for the Airborne Division after D-Day. The memo suggests that these operations had been requested from 21st Army Group. The third operation described was effectively what became Operation Wild Oats, albeit without the code name. Its possible circumstances were described as ‘About D+7/D+8 the breakout from the bridgehead is being staged against considerable opposition’ with the task of ‘To drop and seize the high ground 8 miles N of Falaise’. This, again, was almost identical to the scenario envisaged in Exercise Wake.

The air commanders subsequently expressed grave reservations about the launching of airborne operations in daylight. On 30 May Hollinghurst, the Air Officer Commanding 38 Group, wrote a memorandum to Leigh-Mallory at AEAF. He suggested that landing airborne forces at night during a no-moon period would be problematic, and that within six days of D-Day a no-moon period would begin. Morning mists were identified as a problem regarding dawn landings:

The alternative is of course normally to limit the launching of the airborne divisions to moonlight conditions e.g. any 6 days each side of the full moon, confining operations under other conditions to such emergencies as warrant us accepting what may be crippling casualties. The acceptance of this principle (which does not of course rule out small operations in dark conditions) is strongly recommended.

Hollinghurst’s proposal, if accepted, would have effectively curtailed airborne operations to only being able to take place on several days out of each month regardless of the tactical situation. This arbitrary policy, which would have been a ridiculous waste of resources by leaving men and aircraft out of action for the majority of the time, suggests that even before D-Day the air commanders were not totally committed to airborne forces as a concept and were not willing to try very hard to help get them into action. As a result of Hollinghurst’s memo the air forces expressed concerns over the launching of airborne operations.

On 2 June a conference was held at TCCP at Eastcote to discuss the air plan for a possible operation in conjunction with VIII Corps, which was given the code name of Wild Oats.2 It was considered that no further planning could take place regarding Wild Oats, pending a decision from AEAF regarding the viability of daylight operations, and that a night operation would therefore be considered. That a policy on whether airborne operations could or could not be launched in daylight had not been agreed so late, only days before D-Day, is both troubling and perhaps indicative of the extent of the power of veto that the air forces had over the launching of airborne operations.3

On 3 June a map was issued by HQ Airborne Troops to 21st Army Group, British Second Army and US First Army showing intended air routes for planned airborne operations. The map again clearly shows Wild Oats taking place east of the Orne in an area almost identical to Exercise Wake.4 This supports the conclusion that prior to D-Day Wild Oats was seen as an implementation of Exercise Wake. The map showed the routes that would be used to transport British and US airborne forces on D-Day, with waypoints code-named Cleveland, Austin, Elko, Flatbush, Spokane and Paducah. Presumably these routes would have been re-used for any follow-up operations. However, the map very clearly shows the air route as turning around just inland from Utah Beach, Sword Beach and the Caen to Falaise road. Whilst these might have been notional, they do indicate the Allied planners’ thinking. Several days later on 6 June 1st Airborne Division issued a map trace of the planned divisional layout for Wild Oats, which showed the division as landing around Évrecy.

However, once the Allies landed the situation and rate of progress altered plans. The Allies had not secured as much ground as had been hoped, and as a result the schedule for landing follow-up formations began to slip. This was also exacerbated by weather affecting shipping. VIII Corps would therefore arrive on the Continent later than planned. Wild Oats would be called upon by XXX Corps instead before O’Connor could land in Normandy.

Lieutenant General Bucknall, the commander of XXX Corps, was clear that he had been allocated a task of expanding the beachhead soon after D-Day. The notes from Bucknall’s verbal briefing before D-Day suggest that he was planning for a breakout operation in his sector on D+4, code-named Perch, and that 7th Armoured Division were being earmarked to make what Bucknall described as a ‘step forward’. Bucknall thought that the Germans would be bound to counter-attack the landings, arguing that ‘there is no doubt that his armoured counter-attacks will be serious – more serious than the coastal defences’. Accordingly, on 8 June Bucknall issued his orders for Operation Perch.

Map 5: 1st Airborne Division drop zones, routes and objectives for Wild Oats. (Source: TNA WO 171/392, TNA WO 171/592 and TNA WO 171/594)

Dempsey met with Bucknall at 1730 on 8 June after meeting Montgomery several hours previously. Dempsey told him that he wanted 7th Armoured Division – who had begun landing on the evening of D-Day – kept out of the battle until 10 June, presumably to keep them available for breakout operations. Bucknall was informed by Dempsey that 7th Armoured’s objective would likely be Villers-Bocage, and that they would be operating in conjunction with I Corps. Bucknall’s diary for 8 June records that he visited 8th Armoured Brigade, an independent armoured brigade, to arrange the attack on Villers-Bocage.5 They would capture Tilly-sur-Seulles as a start line for Perch.

On 8 June Dempsey met Crocker at 0830 and told him to be prepared to operate east of the Orne in two or three days’ time, with a view to capturing Caen from the east. He then saw Montgomery at 1430, before meeting with Bucknall at 1700 at XXX Corps Headquarters. Dempsey’s diary records that he told Bucknall to keep 7th Armoured Division out of the battle until the next day, and then to use them to advance to Villers-Bocage and ‘swing east on axis Tilly-Noyes so as to come in on the flank and rear of the divisions attacking I Corps’.6

The same day Montgomery wrote to his confidante at the War Officer, the Director of Military Operations Major General Frank Simpson, to update him on the progress since D-Day: ‘The Germans are doing everything they can to hold on to Caen. I have decided not to have a lot of casualties by butting up against the place; so I have ordered Second Army to keep up a good pressure at Caen, and to make its main effort towards Villers-Bocage and Évrecy and thence SE towards Falaise.’7

This suggests that Montgomery had almost certainly told Dempsey to aim for Caen via Villers-Bocage. On 9 June 1944 Montgomery’s Chief of Staff, Major General Francis de Guingand, signalled Montgomery ‘Have you any ideas use 1 Airborne Div’. This signal suggests that ideas regarding the use of 1st Airborne Division were still relatively fluid, and that Montgomery was also keeping actively involved in decision-making regarding their employment.

It appears that the modification of Wild Oats originated from Dempsey. At 1000 on 9 June Dempsey met Montgomery and informed him that he was planning an operation with 7th Armoured, 51st Highland and – possibly – 1st Airborne Division. Montgomery obviously agreed to Dempsey’s plan, as he then met with Crocker at noon and explained the plans for 7th Armoured Division and 51st Highland Division, and his plan to drop 1st Airborne Division south of Caen if both attacks went well. Several hours later at 1200 Dempsey met the commander of I Corps, Crocker, and informed him of his plan. Dempsey stated to Crocker that he was to be prepared to launch his part of the operation on 11 June, and that ‘If the attacks of 7 Armd Div and 51 Div went well, the landing of 1 Airborne Div to the SOUTH of CAEN might well be decisive’.8

I Corps commanded the British and Canadian divisions that that landed on Juno and Sword Beaches on D-Day. I Corps Instruction Order No.1 issued on 5 May 1944 does not mention potential airborne operations, but does raise the possibility of 3rd Division and 51st Highland Division mounting a converging attack either side of the River Orne if Caen had not been captured by D+5/6.9

At 1300 Dempsey discussed the scheme with Browning, explaining that he wanted the operation to take place on the evening of 11 June or later. Dempsey’s diary states that Browning then set in motion the machinery for planning the operation and carrying it out.10

Meanwhile Bucknall still planned to advance XXX Corps south from the area around Tilly as part of Operation Perch and XXX Corps Operation Instruction No. 2 was issued the same day. The intention was to capture the high ground around Hottot and Juvigny with 7th Armoured Division providing the armoured thrust. However, this advance made slow progress against stiff opposition. Bucknall’s diary entry for 9 June states that Montgomery had spent an hour with him and expressed ‘delight’ at progress and approved his plans.11

Plans for Wild Oats were formulated quickly. On 10 June a planning team from 1st Airborne Division flew to Normandy. They attended a conference at Second Army Headquarters on Wild Oats, which was described as an operation in conjunction with 7th Armoured Division and 51st Highland Division in the Évrecy area. A subsequent conference then took place at XXX Corp’s headquarters.

On Saturday 10 June Dempsey held a conference with Bucknall, Crocker and Browning, after an earlier meeting with Montgomery and Bradley. Dempsey outlined his plans for Wild Oats and stated that 1st Airborne Division would be dropped to work in conjunction with whichever division made the best progress. Dempsey also ordered Bucknall to switch 7th Armoured Division further west and to make a wide hook through Villers-Bocage. Although XXX Corps’ war diary suggests that Bucknall was considering this move before his conference with Dempsey, the latter was vehement that the decision was his:

Met commander 30 Corps at BAYEUX railway station. He told me that 11H [11th Hussars], in contact with American 5 Corps, were making good progress SOUTH of the road from BAYEUX to CAUMONT. I told him to switch 7 Armd Div from their front immediately, to push them through behind 11H and endeavour to get to VILLERS BOCAGE that way. Provided this is carried out with real drive and speed, there is a chance that we will get through before the front congeals.

Bucknall’s diary for 10 June recorded that 7th Armoured Division’s attack began at 0700, and Dempsey visited Bucknall shortly after at 0930. There was a conference at Army HQ at 1700 with corps commanders and ‘Airborne Comds’ – presumably Browning – on what Bucknall described as ‘plans for a “Carnival!”‘. His diary entry for 10 June also described how 7th Armoured Division had been held up by Panzer Lehr at Raury.12

I Corps Operation Instruction No. 2 issued on 10 June outlined a plan for 51st Highland Division, with 4th Armoured Brigade under command, to advance to and capture the high ground south of Caen and control the road exits leading south, south-east and east from the city.13 The aim was for 4th Armoured Brigade to reach Hubert Folie and occupy the ground between St Andre-sur-Orne and Bourguébus. The operation was to include preparatory naval and air bombardments of areas of Caen. The move of 51st Highland Division towards the start line was a particular problem, as at the time of the Operation Instruction being issued the Division was west of the Orne. At the time that the Operation Instruction was issued on 10 June a junction between the two pincer movements was clearly still envisaged, for ‘liaison with 7th Armoured Division’ was included. Intriguingly, I Corps Operation Instruction No. 2 mentioned rather vaguely that ‘1 Airborne Division may take part in the operation. There are alternative plans depending on the situation which may develop on 11 Jun. One provides direct help to 51 (H) Inf Div and the other indirect. Details separately.’

Whilst modifying the plan for 1st Airborne Division based on progress made was no doubt sensible, it also left virtually no time for more detailed planning. There is no mention of this operation, which was codenamed ‘Smock’, in the 1st Airborne Division war diary, and neither the I Corps or 51st Highland Division Operation Instructions make any further reference to the part that the Airborne Division might have played in the operation.

Dempsey and Bucknall discussed the plans for 7th Armoured Division and 1st Airborne Division – interestingly, 51st Highland Division had already disappeared from his thinking. Bucknall was ordered to advance 7th Armoured Division on the axis Hottot–Noyers while maintaining a strong flank at Villers-Bocage. In the early evening he then met with Crocker, Bucknall and Browning at Second Army Headquarters. They discussed the plan to land 1st Airborne Division on 13 June and Dempsey explained that it would either be with I Corps or XXX Corps, the decision being made the next day depending on progress in the different sectors.14

Meanwhile, back in England the air planning for Wild Oats had begun. On 10 June Air Vice Marshal Harry Broadhurst, the commander of 83 Group, flew back to Britain after meeting with Dempsey. Broadhurst, who commanded one of the tactical air formations supporting 21st Army Group, was one of the few airmen that Montgomery trusted. He explained the plan for Wild Oats to De Guingand, and presumably his superiors at AEAF, Coningham and Leigh-Mallory. In his daily signal De Guingand told Montgomery that ‘there seemed to be a bit of a problem regarding the flight in’.

Operation Perch was swiftly modified. On 11 June a document that originated from XXX Corps described the concept of what would become Wild Oats as a ‘30 Corps project for employment of 1 Airborne Division’. The object would be to prevent the enemy from escaping, with Évrecy and Bully being held as pivots. XXX Corps Operation Instruction No. 3 for Operation Wild Oats was issued later the same day. The decision as to whether the operation was to be launched would be taken by Dempsey at Second Army. At this stage the plan still envisaged pincers attacking either side of Caen, with I Corps sending 51st Highland Division south from the Orne bridgehead to capture Démouville, Banneville and Grentheville, and 4th Armoured Brigade to capture Verrières. 1st Airborne Division would land around Évrecy, Hill 112 and St Martin and link up with 7th Armoured Division. The Airborne Division would come under the control of XXX Corps immediately after landing.

Notably the Operation Instruction stated clearly that 7th Armoured Division had to be established around Évrecy before the Airborne Division landed. Bucknall intended that the airborne drop would take place with 7th Armoured Division already holding the drop zones, which would have prevented the risk of an opposed landing or the armoured division having to fight to relieve the airborne troops. However it is unclear whether this was merely an instruction, or whether the drop would only have taken place if 7th Armoured Division had reached Évrecy. Post-war, however, the opinion would take hold that Wild Oats would have been similar to Market Garden, namely an airborne division being dropped before an armoured division advanced to link up with it. Bucknall’s instructions suggest however that it was intended to be an armoured advance, with an airborne division being dropped to consolidate the objective with infantry once it had been reached.

The intelligence available to XXX Corps identified correctly that Panzer Lehr had been drawn into the Germans’ defensive line rather than being held back for an armoured counter-attack. Unidentified tanks had been observed moving behind the German lines, but these were thought to be from 11th Panzer Division coming from Bordeaux or 2nd SS Panzer Division coming from Toulouse. A XXX Corps Intelligence Summary issued on 13 June predicted that the stiff opposition put up the by the Germans on the Corps sector was the prelude to an orderly withdrawal. It was believed that Panzer Lehr might withdraw to defensive positions around Villers-Bocage, and that this could then lead to a stand on Mont Pincon further south. 2nd Panzer Division had not been identified in the battlefront by any intelligence.

Bucknall’s diary for 11 June records that he held a conference with Browning and their staffs at 1830 on Operation Wild Oats. Bucknall noted that ‘a satisfactory plan evolved but the op is NOT popular!’ Unfortunately Bucknall did not record with whom the plan was unpopular or why. Meanwhile 7th Armoured Division’s progress had continued to slow – Bucknall put this down to the close county and lack of infantry support. He recorded in his diary ‘German build-up becoming hotter! We shall now head for Fillers Bocage [sic] sharply!’15

At 1800 on 11 June Leigh-Mallory held a conference to discuss what was referred to as Montgomery’s proposal for Wild Oats. Urquhart, Hollinghurst and Montgomery’s intelligence chief Brigadier Bill Williams were present. At the same time Group Captain McIntyre, AEAF’s Airborne Operations Officer, had flown to Normandy to discuss the plan for Wild Oats with 21st Army Group headquarters. Leigh-Mallory opened the conference in a negative manner, as recorded in the minutes: ‘He thought this would be a very expensive operation, and that the Army should realise that if it were undertaken it might prejudice the planning of future airborne operations for three months to come.’

The troop-carrier commanders, Williams and Hollinghurst, were unwilling to fly the airborne force in during daylight over a heavily defended area. They proposed mounting the operation at night, but Leigh-Mallory cautioned that this would mean flying over the Allied fleet at night and that Allied naval anti-aircraft gunners were ‘loose on the trigger’. Urquhart said that he would much rather fly in during daylight given the short notice before the operation, the lack of time to brief his division and that a night drop would leave them badly scattered. Hollinghurst thought that it would be impossible to fly in during daylight. Williams suggested a route crossing the French coast over Utah Beach and flying over mainly Allied-occupied territory.

Leigh-Mallory then spoke to Admiral Ramsay’s chief of staff, Rear Admiral George Creasy, by telephone. Creasy told Leigh-Mallory that no guarantees could be given that Allied naval forces would not fire on friendly aircraft if Wild Oats was mounted at night. Leigh-Mallory then telephoned De Guingand to inform him that the operation could not take place at night and that as there was no guarantee that the Allied aircraft would not be faced by friendly fire the operation could not take place.

De Guingand described Leigh-Mallory as ‘very much against it’, and it seems that De Guingand agreed with him, describing his objections as ‘pretty weighty’. The naval forces felt that it would be difficult to prevent anti-aircraft guns from firing at the transport aircraft if the flight in took place in darkness. Leigh-Mallory objected to a daylight operation, as the proposed landing and drop zones were all within range of enemy flak. De Guingand himself described it to Montgomery as a ‘risky undertaking’, and quite presciently, stated that ‘It seems difficult to realise how the Division will be able to pull itself together and become a fighting force under these conditions’.

Even while Wild Oats was being rejected, Dempsey still intended for 51st Highland Division to attack south-east of Caen. At 1915 on 11 June a signal from 1 Corps informed 51st Highland Division that the proposed operation was to be code-named Smock, which is testament to the extent that the Airborne Division played in the initial planning.16

Despite the disagreements with the Air Forces, the 1st Airborne Division plan for Wild Oats was issued on 12 June. The initial drop would take place just before dawn at 0425 on 14 June, to take advantage of darkness for the approach flight. 1st Parachute Brigade would land on a drop zone north-east of Évrecy beginning at 0420, secure the landing zones for the division’s gliders and then hold the sector north or north-west of Évrecy. 1st Battalion would capture and hold Évrecy and prevent the Germans from using the road network through the village. 2nd Battalion would occupy the high ground north-west of Évrecy, and dominate the approaches to Évrecy from the north, including from Gavrus. 3rd Battalion would hold the landing zone for the glider landings and then occupy high ground south-west of crossroads at Tourmauville. Brigade Headquarters would be established in Évrecy.17

4th Parachute Brigade would take off in US aircraft from Cottesmore and Spanhoe. They would land on a single drop zone, capture and occupy the high ground around Hill 112 and be prepared to operate in conjunction with an armoured brigade around Baron. 156th Battalion would occupy the high ground to the north-east and consolidate their positions. 11th Battalion would take up a defensive position covering the approaches to the high ground to the west and north-west and attack and capture an enemy gun battery, and 10th Battalion would be in reserve, covering approaches from the south-east.18

Intelligence regarding German positions in the Évrecy area seems to have been sketchy and scant information was passed to the Airborne Division. The airborne troops would literally be jumping into the unknown, and the possibility of having to land in drop zones occupied by the enemy was raised.19

1st Parachute Brigade’s orders covered Operation Wild Oats and another operation code-named Sampan.20 Brigadier Lathbury briefed his officers on 12 June, and explained Sampan and Wild Oats as a co-ordinated offensive to cut off the enemy in Caen by moving 7th Armoured Division to Villers-Bocage and then to Évrecy, and by moving 51st Highland Division south through the airborne bridgehead east of the river Orne. The brigade was given two potential roles – to fly in to the area of Ranville, Démouville and Sannerville to co-operate with 51st Division or to land north-east of Évrecy on 13 June.

It is noticeable however that the Wild Oats option contains much more detail in the 1st Brigade war diary. 3rd Battalion would occupy high ground south-west of Tourmauville and deny approaches into Évrecy and Gavrus. 2nd Battalion would occupy high ground north-west of Évrecy and dominate approaches to Gavrus and the main road from Évrecy to Landes. 1st Battalion, meanwhile, would capture and hold Évrecy itself to prevent the enemy using the approaches through the village. If the situation permitted 1st Battalion would also establish a strong cover patrol at Mondeville. It was anticipated that elements of 7th Armoured Division would be in the Évrecy area as early as possible on the morning of the operation and would then head towards Hill 112. An amendment to Lathbury’s original orders suggested that ‘enemy tanks may anticipate them’. He also anticipated a lack of information prior to take-off and warned officers to be prepared:

There will be no definite or detailed information regarding enemy dispositions and strength on, and in the vicinity of, the DZ prior to landing. It is therefore the responsibility of sub units on their own initiative to deal with and liquidate immediately any enemy posts interfering with landings. The necessity for getting off the DZ and moving to RVs with all possible speed must, however, be stressed on all ranks who are not immediately concerned with mopping up enemy posts.

As dawn broke on 12 June 7th Armoured Division resumed their attacks on Tilly but were held up. As the front had started to congeal Bucknall ordered 7th Armoured to pull out and redirect its thrust west towards Villers-Bocage, a move which had been first discussed two days previously. Bucknall wrote that the opposition on 7th Armoured Division’s front was ‘somewhat tough’. He met Dempsey at 1130, and they agreed – in Bucknall’s words – on a right hook by 7th Armoured Division to Villers-Bocage. He issued orders for 7th Armoured Division to disengage, and their leading tanks crossed the start line for their new move at 1600. The move went well and by nightfall the Desert Rats were north of Caumont, east of Villers-Bocage. Browning also visited Bucknall for lunch and tea. Meanwhile Wild Oats was postponed for 24 hours. As an illustration of how behind the Allied build up was, Bucknall’s third division – 49th Division – had only just started coming ashore.21

51st Highland Division’s Operation Order No. 2 was issued at 1530 on 12 June. The intention was for the division to capture the line between Verrières, Bourguébus, Cagny and Touffreville with the object of preventing enemy movement south of Caen, forming a pivot in the area of Cagny and dominating the Caen-Falaise road and the bridges over the Orne and Laize at St Andre-sur-Orne and Laize-la-Ville. In the first phase 152nd Brigade would capture St-Honorine la Chardonnerette, Cuverville and Démouville. In the second phase 4th Armoured Brigade would advance and capture the area of Bourguébus, Tilly-la-Campagne and Verrières. Finally, phase three would see 154th Brigade consolidating the area of Le Mesnil, Fremental and Grentheville. Assembly and concentration was again highlighted as a concern. The division was to concentrate around Ranville and Benouville in the airborne bridgehead, in what was already an increasingly congested area.22 51st Highland Division’s Operation Order makes no mention of an airborne element, nor of operating in conjunction with 7th Armoured Division. It is possible that the lack of progress made on 11 June had led to the pincer movements effectively being isolated.

However, less than six hours later at 2115 on 12 June I Corps issued an order postponing Operation Smock. The operation was amended to take place on 13 June, and the objectives were modified to St Honorine, Cuverville and Escoville. The order to postpone Smock probably originated from Second Army, as at 1530 on 12 June Dempsey ordered Crocker not to move 4th Armoured Brigade in view of the threat of a German counter-attack north-west of Caen. 51st Highland Division were ordered to ‘improve their positions’ east of the Orne overnight, which appears to be a tacit acceptance that they would not be able to attack to the south. Although there is no reference to Operation Smock in Airborne documents at either corps or divisional level, 1st Parachute Brigade’s Operation Order for Wild Oats includes a reference to Operation Sampan, with the intention to land in the Ranville, Demoville and Sannerville area to co-operate with 51st Highland Division.23

7th Armoured Division continued their advance the next day on 13 June and reached Villers-Bocage at 0845. The village was clear of enemy but an attempt to advance on Point 213 had to be abandoned after fierce German counter-attacks led by Michael Wittmann and the Desert Rats withdrew to the west to Tracy Bocage. A XXX Corps report the next day correctly identified that 2nd Panzer Division had arrived in the battlefront. Bucknall described the right hook by 7th Armoured Division as successful and that they were in command of Villers-Bocage. Yet by the afternoon his diary records that a heavy counter-attack by 2nd Panzer Division had beaten 7th Armoured Division out of Villers-Bocage.24

On the same day that Michael Wittmann repulsed the Desert Rats the generals were arguing fiercely about Wild Oats. On 13 June Leigh-Mallory discussed Wild Oats with De Guingand. Montgomery had reacted furiously to Leigh-Mallory’s refusal to launch the operation:

Do not repeat not understand refusal of LM to carry out airborne operations. I am working to create such favourable conditions as would make dropping of One Airborne Div in Évrecy area a good operation of war and one which if successful would pay a good dividend. Conditions have not repeat not yet been reached but may well be created by 14 June. LM should come over and see me and ascertain true form before he refuses to carry out an operation. He could get here by air in 30 minutes.

Although Montgomery’s reaction – and not to mention his description of Leigh-Mallory as a ‘gutless bugger’ – was no doubt tactless and not conducive to inter-service relations, his argument that Leigh-Mallory should have flown to France does raise a valid point. The separation of headquarters across the Channel was not liable to encourage swift planning, particularly if the army wanted an operation mounted quickly. And if headquarters were separated, commanders needed to be prepared to communicate and travel back and forth as operations required.

That Leigh-Mallory felt comfortable vetoing the operation without flying to France to discuss it with Montgomery or Dempsey – and that neither of the generals attempted to override him – alludes to the power that the air commanders had over the launching of airborne operations. It is of course possible that if Leigh-Mallory had been more involved in the early planning of Wild Oats he may have been more amenable. Leigh-Mallory had form for being over-pessimistic with his judgement of airborne operations, as shown before D-Day. Richardson, Montgomery’s chief planner, felt that Leigh-Mallory’s sending of a signal rather than a visit caused a deterioration in personal relations. He described the atmosphere at HQ AEAF as a ‘dangerous crisis’.25

Despite the air forces’ objections Wild Oats was not completely cancelled and seems to have been quietly held in readiness by the army in case conditions changed. It was postponed for 24 hours by 21st Army Group on 12 June, for another 24 hours on 13 June and then suspended on 14 June, but held in readiness at 48 hours’ notice, presumably in case conditions became favourable. On 13 June De Guingand wrote to Montgomery and informed him that Browning had met Leigh-Mallory, and that Dempsey had proposed a new date for Wild Oats on 15 June. On 16 June the division was placed at 72 hours’ notice, and Wild Oats was only cancelled for good on 17 June.

Despite these postponements preparations for Wild Oats continued on the Continent. A message received by 30 Corps on 13 June indicated that an advance party from 1st Airborne Division would be arriving the next day. On 14 June the re-supply plans for Wild Oats were confirmed, code-named Whiterocks.

1st Airborne Division had not exercised with tanks before D-Day, a deficiency that had been noted by some airborne commanders. Hackett’s 4th Parachute Brigade held Exercise Jael, with the object of practicing co-operation with tanks. The exercise was clearly influenced by Wild Oats, and the narrative for Jael gives an insight into how Hackett foresaw the operation developing. The operation had been launched on the night of 15 and 16 June, and 7th Armoured Division had reached Évrecy in time to hold the drop zones. Significant German traffic had been encountered in the area, including the headquarters of 12th SS Panzer Division. Cutting the Villers-Bocage–Caen road was the key objective. It is perhaps insightful that the one airborne commander who had given serious consideration to co-operation with tanks, Brigadier Hackett, was a cavalryman who had fought in tanks in the Desert. Lathbury’s 1st Parachute Brigade also gave some thought to co-operation with armoured units. Perhaps also spurred on by Wild Oats, on 17 June Lathbury issued 1 Parachute Brigade Tactical Notes No. 7, ‘Co-operation with tanks’.

On 14 June Montgomery wrote to Simpson again. Although he projected his customary confidence that everything was going to plan, he also acknowledged the reverse at Villers-Bocage.

I had to think again when 2 Pz Div suddenly appeared last night. I think it had been intended for offensive action against 1 Corps. But it had to be used to plug the hole through which we have broken in the area Caumont – Villers-Bocage . . . So long as Rommel uses his strategic reserves to plug holes – this is good.26

Wild Oats was the last plan to use airborne forces in the Battle of Normandy. It is not clear exactly why, but a combination of the air planners’ objections and the early stalemate followed by rapid progress towards the end of the battle must have played a part. This demonstrates one of the key challenges of airborne planning. In a stalemate it was uncertain if the ground forces would be able to link up in time, yet in mobile operations plans could not be drawn up in time and landing areas could be overrun quickly. Future set-piece operations in Normandy such as Epsom, Goodwood, Cobra and Bluecoat would be drawn up without an airborne component. This is despite several operations bearing strong similarities with Exercise Wake and the concept for airborne operations developed before D-Day.

De Guingand criticised the planning of Wild Oats by Second Army. He felt that the air commanders – in particular Leigh-Mallory – had not been informed about the operation until far too late, and hence had not been involved in its early planning and were therefore able to express their negative opinions too easily. De Guingand was concerned that Dempsey was accepting his proposed operation for 1st Airborne Division as a fact and was basing the rest of his operations on it, when, as has been previously seen, the air forces effectively held a veto over the launching of airborne operations. That they could be planned and proposed, without reference to the air forces who would deliver them, and by staffs who had no prior experience of planning airborne operations, may go some way to suggesting how subsequent operations transpired. There was clearly a disconnect between Montgomery and Dempsey and the air commanders in terms of airborne planning.

Dempsey appears to have been a prime mover in the plan for Wild Oats. In fact, he played a much more prominent and assertive part in the planning and decision-making for Wild Oats than has previously been thought. Dempsey has frequently been characterised as serving as a chief of staff while Montgomery micro-managed Second Army, but the story of Wild Oats suggests a much more complex picture.

Whilst Operation Perch had been planned in concept before D-Day, it is striking that what had been originally proposed in the guise of Wild Oats as a two division pincer-attack either side of Caen, linking up with an airborne division, was gradually reduced to a single attack by a weak armoured division without airborne assistance.

The cancellation of Wild Oats was a low-point in army-air relations during the Normandy campaign. It is hard to escape the conclusion that the air commanders dominated the decision-making. Leigh-Mallory seems to have been hostile to the operation from the start, and while Hollinghurst and Williams attempted to find a way in which the operation could be mounted, Urquhart played a minor role in the air conference on 11 June. The air commanders essentially held a veto over the launching of airborne operations regardless of the effect on the land battle, and which even Montgomery himself – let alone Urquhart – could not challenge. It has been suggested that this veto over the launching of airborne operations was the long-term price of securing the Royal Air Force’s co-operation in developing airborne forces earlier in the war.27 Whether this is the case or not, it is hard not to see parallels with the way in which the air commanders would later dominate key decision making during the planning of Operation Market Garden, particularly the choice of drop zones and limiting the number of lifts that could be taken in one day.

The Wild Oats debacle does seem to have led to something of a ‘clear the air’ moment between Montgomery and Leigh-Mallory. On 14 June Leigh-Mallory sent a signal to Montgomery regarding proposed roles for 1st Airborne Division, and the two commanders began to discuss airborne operations in a way that would have been useful prior to the conception of Wild Oats.

Frictions between the Army and Air Force commanders dogged the Allied forces throughout the Normandy campaign, particularly in 21st Army Group. On 7 July Montgomery wrote to Brooke stating that he had spoken directly to Tedder about his problems with Coningham, who he felt that the Army had a lack of confidence in. He also felt that the Army was not getting the air support that it needed due to friction between Leigh-Mallory and Coningham. In the same letter, however, Montgomery also conceded that Dempsey and his staff at Second Army ‘do not know a very great deal yet about how to wield air power’, but that he also felt that Coningham was aware of this and exploited it for his own purpose. Montgomery, in his usual way, explained that he was trying to ‘teach’ Dempsey about air matters.28

It is interesting to reflect on what might have been with Wild Oats. The original concept borrowed much from the lessons of Exercise Wake, carried out by VIII Corps before D-Day. Like Wake, Wild Oats envisaged dropping an airborne division behind the German front lines and relieving it with an armour-led attack. In the event, the advance took place west of Caen rather than to the east as intended during Wake, and the operation was carried out by XXX Corps, as there was not enough space in the bridgehead for VIII Corps to land in time. VIII Corps would later carry out another attack to the west of Caen during Operation Epsom that bore strong similarities to Wake, but without airborne assistance.29

How might Operation Perch have fared if 1st Airborne Division had been dropped around Évrecy as hoped? As events at Arnhem would show, airborne troops were extremely vulnerable to armoured counter-attacks if they could not be reinforced swiftly. Even though the arrival of 10,000 airborne troops south of Panzer Lehr’s positions, and in a crucial area, would have caused the Germans a great deal of disruption, the swift reaction of the Germans to Allied attacks during the 1944 campaign suggests that any air landing would have been hotly received.

Bucknall’s performance throughout the Battle of Normandy was a disappointment to Dempsey, who never seems to have been an admirer, and Montgomery who had specifically requested him to command XXX Corps against Brooke’s judgement. Bucknall had previously commanded 5th Division in Italy and letters in Bucknall’s papers suggest a very warm relationship between himself and Montgomery, going as far as to virtually beg the latter to take his division back to Britain for Overlord.30

After the end of the war Chester Wilmot corresponded with most of the senior commanders in North West Europe, including Bucknall.31 Even in 1947 Bucknall and Dempsey recalled Perch and Villers-Bocage very differently. Bucknall felt that the plan for Perch was his and that he merely asked Dempsey’s permission to carry it out. He did not recall being briefed on the wider objectives of Noyers and Évrecy or the plan for Wild Oats on 12 June and felt that if they had been mentioned he would ‘certainly have remarked upon it’ as it would have gone beyond his own plan and the resources available to him. He could not recall anything regarding the airborne plans to work in conjunction with XXX Corps and had made no preparations for it. He stated that ‘It would have required most careful preparation and co-ordination’. He recalled Perch as being aimed at a ‘sharp blow’ to extend the beachhead and nothing more, and that it was a Corps objective, not an Army one. He saw Second Army’s objective as Caen, and he felt that his operations were not a priority in that regard.

Wilmot replied to Bucknall that Dempsey had told him that he had given orders for 7th Armoured Division’s switch to Erskine direct and told Bucknall, and that the plan for an airborne drop at Évrecy was very much in his mind. Bucknall’s response was that ‘this may be so, but it was not mentioned to me to the extent of requiring extrication, or more troops, and was also very limited, quite rightly, in artillery ammunition allotment’. He went on to say that:

Gen Browning and I had discussed with each other the various possibilities in which we might with advantage employ Airborne cooperation. This was not one of them. Moreover, it is for consideration whether such an op would not have been a dispersion of effort here? The main battle was proceeding for the capture of Caen. Perch was a subsidiary op to fix the front of 30 Corps (and incidentally act as a diversion). 30 Corps was told not to get involved again and to work out the time and space problem.

Wilmot replied that Dempsey had clearly regarded Perch as a more substantial operation, and refers to Dempsey’s diary in which he saw XXX Corps as threatening Caen from the west, as well as identifying plans to envelope the city from the east and west. Wilmot suggested that Dempsey had seen Perch as a ‘stepping stone to much greater things’. Bucknall responded that he had conceived Perch himself as a local effort to break up opposition on his front, but that it was seized upon by Dempsey as a ‘possibly valuable adjunct’ to the plan to capture Caen if the battle went well. Bucknall also stated that the success of Perch was not essential to the capture of Caen and that plans to capture Caen were made irrespective of XXX Corps. He also stated that he could not remember the code name Wild Oats, but that his Corps staff and the Airborne staff were not enthusiastic about the operation.

Wild Oats has been subject to some inaccurate descriptions by historians, which reflects the wildly differing accounts from the senior commanders involved. One author has even described the operation as being planned for near Carpiquet in the 12th SS Panzer Division area to block German reinforcements, but was rendered unnecessary by a Canadian ground advance.32 Whilst Wild Oats was frequently mentioned before D-Day, the concept prior to the landings featured an airborne drop linking up with a single armoured thrust out of the beachhead. The modified plan proposed in the days after D-Day featured two pincer movements east and west of Caen. 7th Armoured Division would advance to the Évrecy area, while 51st Highland Division would attack out of the airborne bridgehead east of the River Orne, to occupy the high ground around Bourguébus.

Veterans recalled Wild Oats very strongly in their memories post-war, and it is the most-cited example of an operation being cancelled at the last minute. The senior commanders seem to have been fairly sceptical about Wild Oats. Urquhart described his relief in his memoirs, and described it as ‘aptly named’.33 John Frost was also not impressed with the plan: ‘. . . we were very nearly called upon in the early stages and some of the tasks envisaged were hazardous in the extreme. One of the occasions we were to drop virtually on top of one of the panzer divisions attacking the beachhead.’34

Panzers do indeed feature strongly in thoughts about Wild Oats. Major John Waddy commanded a company in 156th Parachute Battalion:

It got very frustrating. We actually loaded the aircraft twice if not three times, and another 24 hours cancellation, then another 24 hour stand down. One of them we were very relieved, we got as far as not quite sitting in the aircraft, on the airfield in Normandy, which was going to drop the Division on the ridge South-West of Caen, Carpiquet. Just ahead of an armoured push Op Goodwood. That kept being put back 24 hours and then finally cancelled. And we knew that that it was going to be hard because we were ordered to carry Hawkins Grenades, each man was issued with two of these. And the drill was that as soon as we landed we were going to use these Hawkins mines to blow weapons pits. We knew that we were going to be attacked very quickly. We were lucky that we didn’t do it as afterwards we heard that there was a Panzer Division on the ridge. I think it was cancelled because the ground forces weren’t ready and hadn’t achieved their first objective.35

William Carter was serving with 1st Parachute Battalion:

We went to Brize Norton – I think the actual invasion had started then – and we went down there, we were going to be part of an operation, I think they were being held up at the Falaise Gap, and that’s where we briefed on dropping to bridge the gap where they were trying to break out. But I think they foresaw that it was going to be a suicidal thing because at the last minute we were cancelled.36

Mike Brown was serving as a glider pilot. His recollections show how the glider pilots were supporting both airborne divisions, and that many of the crews who returned from Normandy were at readiness again almost immediately:

The people hadn’t gone on D-Day had already been briefed for another operation. And some gliders had been loaded up ready to go. And some of us, about 10 of us, about 10 crews, were needed to make up the numbers. When we got back to Down Ampney they wanted some of us to go join the other lot and go again. And we were briefed there and then to go. This was, I think it was Wild Oats it was called.37

John McGeough was also serving as a glider pilot. His memories included the location of Wild Oats, possibly as glider pilots had been briefed in more detail: ‘Another plan which was never put into operation was to land gliderborne troops near the village of Évrecy south of Caen. And our objective was to take out a large house which was the headquarters of the Gestapo. Of course that was cancelled.’38

A great deal of hindsight has been applied to understanding of Wild Oats. It is often difficult to discern what are memories and what has been influenced by historiography and popular culture. This is not to suggest that any participants might be inaccurate, but to emphasise that the profile afforded to Arnhem, including legions of books, films and TV series, can have a very formative influence. Indeed, veterans thoughts on Wild Oats often reference the threat of German tanks –a key part of the story of Market Garden.

Some elements of Wild Oats were, on the face of it, more sensible than Market Garden. The distance from the start line of the advance to the landing area was much shorter. The Airborne Division would have landed in a much more compact area, and, critically, the airborne force would only have taken off once the armoured units were on the drop zones.

Might Wild Oats have worked? It might perhaps have been a closer-run thing than many historians have predicted, but as with all airborne operations the margins would have been very fine, and highly dependent on the reaction of German units on the ground.