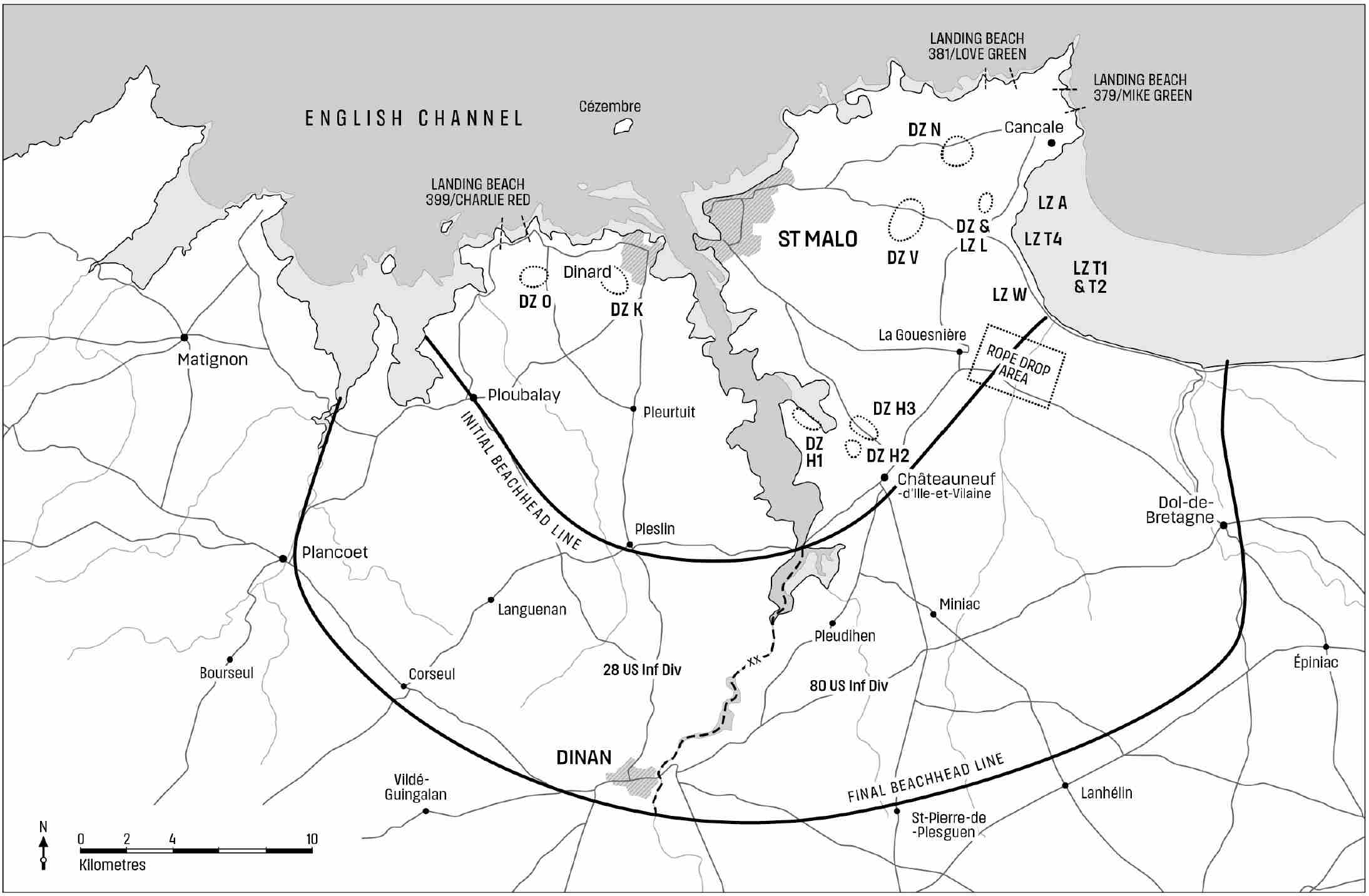

Map 6: Drop zones and objectives for Beneficiary. (Sources: TNA WO 205/845)

The demise of Wild Oats heralded the end of airborne planning in Normandy itself. However, the Allies had already considered potential airborne operations to support the wider campaign in Northern France. In particular, the Brittany peninsula had been identified as an objective due to its deep-water ports, which would be valuable for securing the logistics of the Allied forces. The US Army had a large number of divisions back across the Atlantic waiting to move to Europe, and securing Brittany would enable them to be shipped directly to France.

Planning for airborne operations in Brittany began soon after the D-Day landings. On 14 June De Guingand wrote to Montgomery regarding airborne operations in the peninsula.1 He explained that 21st Army Group staff had held several planning meetings and had concluded that it would be improbable that a separate airborne and seaborne operation for the capture of St Malo would be required, and that it would be easier to capture St Malo overland. While De Guingand felt that it should be considered in case the operational situation might change, with the existing enemy garrison and the need to land on either side of the estuary the Allies would not have sufficient airborne troops without 1st Airborne Division. The naval forces were not keen on an assault by sea as it would take away craft which were urgently required for the build-up in Normandy.

On 18 June Browning sent a paper to HQ 21st Army Group and AEAF regarding airborne operations in Brittany, described formally as ‘project to increase the speed of build-up of Third US Army without distracting from the Overlord operations’.2 Browning assumed that ‘. . . no project is worth consideration by 21 Army Group if it delays the Overlord build-up and operation. The corollary is that no landing craft or ships of the types used for beach landings can be spared from Overlord while the Neptune beaches are used to capacity.’ Browning believed that there would be enough spare shipping to land at least one corps as part of a seaborne assault and that a successful operation could make it unnecessary for First US Army to have to bother about Brittany at all.

Browning’s paper did not mention St Malo, but described the overall strategy of airborne operations in the Brittany peninsula. Specifically, Browning outlined the requirement for any operations to be the capture of an airfield for landing of airportable formations and sufficient moonlight. There would be a suitable moon period between 28 June and 12 July. It would also be essential to wait until the enemy has no reserves available. A target date of 6 July was suggested for the airborne operation with the seaborne element landing seven days later.

Montgomery’s directive M504 of 19 June mentioned that a study was being made

of the possibility of seizing St Malo by airborne operations from England, and then bringing into that port a Corps of Third US Army . . . If this can be done it would enable the whole tempo of the operations to be speeded up, since Third Army would be in close touch with First Army and everything would thus be more simple.3

On 21 and 22 June Leigh-Mallory discussed the St Malo scheme with the AEAF Airborne Operations staff. ‘The Army’ were described as ‘not interested’ in Beneficiary due to the strength of German forces believed to be there.4 There is no evidence to suggest who ‘the Army’ were, or why they were ‘not interested’ in Beneficiary. Despite this apparent reluctance, a conference was held in the AEAF war room on 23 June to discuss airborne operations, including Beneficiary. General Whiteley from SHAEF said that 21st Army Group were not in favour of landing troops in the St Malo area as it was too well held for a successful operation. Eisenhower’s original suggestion that they should drop the Polish Parachute Brigade and one US Parachute Infantry Regiment in the St Malo area had been made subject to agreement by 21st Army Group, who were now definitely against it and thought that St Malo could be occupied by land operations alone. Leigh-Mallory asked whether it was understood when this decision was taken that the airborne assault was to be followed by further airborne landings or seaborne landings. General Whiteley said that this had been realised and even so the scheme had not been thought practicable. The Army were more in favour of an operation which would help them to seize Quiberon Bay after the occupation of St Malo, since they regarded it as the best port for maintaining their forces. Leigh-Mallory thought that the merits of Brest as a port had been very much underestimated and that the strength of German forces in the Brest peninsula had been overestimated. Already the Allies were debating the merits of three of the Brittany ports.

On 22 June Major General Urquhart visited HQ Airborne Troops at Moor Park where Browning outlined his division’s role in Beneficiary.5 Urquhart then conducted his O-Group on 24 June, but while he was completing his orders information arrived that the operation would not take place before 1 August. A co-ordinating conference took place the next day at Eastcote before 1st Airborne Division’s Planning Intelligence Summary was issued on 27 June. The Intelligence Summary focused in detail on the enemy situation in the St Malo area, shows the wealth of intelligence on Brittany that was available to the Allies in 1944, with Appendix A giving an enemy order of battle and Appendix E showing drop and landing zone layouts. The Airborne units certainly seem to have been provided with much more intelligence than during the planning of previous operations, when information ranged from scarce to non-existent, and indeed during future plans later in the campaign.

HQ Airborne Troops Instructions for the planning of Operation Beneficiary were issued on 26 June.6 The object was the capture of the port of St Malo and to hold it for the disembarkation of Third Army. Two alternative methods were proposed. The first was an assault by the US ground forces from the east near Avranches assisted by one parachute brigade group, probably the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, with 1st Airborne Division stood by to reinforce if necessary. The second method was an independent airborne assault followed by seaborne forces from Third Army which would not sail from Britain until St Malo was secured. Naval forces would have to attack coastal defences on several small islands north of St Malo, but apart from that it was hoped that the seaborne troops would be able to sail straight into the port. The second method was favoured by Browning for further planning purposes.

Planning for Beneficiary was to be co-ordinated between Allied Naval Expeditionary Forces, FUSAG (what would later become US 12th Army Group), AEAF and HQ Airborne Troops. HQ Airborne Troops was authorised to plan directly with AEAF, 38 Group and IX USTCC and 504th Parachute Infantry. All airborne forces would be under the command of HQ Airborne Troops, who would provide a Tactical Headquarters to command operations until a corps headquarters arrived from Third Army. HQ Airborne Troops would fly in up to six Horsa gliders. That HQ Airborne Troops – at this time still an administrative headquarters – was planning to take part in an operation for which it had not been established and for which its personnel had not trained, hints at an impetus to get it into battle that would be increasingly evident during the planning for further operations.

1st Airborne Division would be carried in by approximately 300 parachute aircraft and 500 gliders, and 504th Parachute Infantry in about 220 aircraft and approximately 30 Waco gliders. 6th Airlanding Anti-Aircraft Battery was also available to take part if required but its aircraft would have to be provided from the allocation given to 1st Airborne Division. Up to two US Airfield Construction Battalions were shortlisted to take part to repair Dinard airfield. SAS units were also to take part and it was hoped that they would be able to link up with and co-operate with the French Resistance, who were very active in Brittany.

The estimated date for launching Beneficiary would be any time between 6–9 July 1944. The outline plan called for 1st Airborne Division to capture and hold St Malo and a bridgehead east of the River Rance. The division would also be prepared to capture the bridge at La Chambre and after the capture of St Malo be prepared to detach up to one brigade group to assist 504th Parachute Infantry west of the Rance. 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment were to prepare alternative plans for the capture of Dinard airfield and Dinard itself. Browning thought that it was unlikely that the US seaborne troops would arrive for at least 48 hours after the airborne assault and that the airborne troops should be prepared for no relief on the ground earlier than four days after the airborne assault. It is unknown what this advice was based on.

The terrain around St Malo was challenging. The Rance is a steep-sided valley estuary separating Dinard from St Malo, around a mile and a half wide and 10 miles long. The St Malo peninsula itself is high and broken up in the north, but flatter further inland, and there were three road and one rail bridge over river between St Malo and Dinard near mouth. The only bridges over the river were long and high and could have been easily demolished. There were orchards on both sides of the valley and fields in the area were small and bounded by hedges and trees, which would have seriously limited the ability of the airborne forces to manoeuvre after landing. Dinard airfield was heavily defended and intelligence suggested that the runways had been put out of action by the Germans. It was estimated that after capture it might take three or four days to get the airfield operational again.

Unlike earlier plans for airborne operations the planning for Beneficiary included detailed reference to the enemy situation. The 5th Parachute Division were holding the coast between Avranches and St Brieuc. However, if the enemy situation in Normandy deteriorated any further the division would probably be used to reinforce the front line. The 136th Infantry Division were holding the coast from Dinard westwards and there were possibly up to three battalions in the area including around the airfield. Its personnel were mainly Russian, Tartar and Turkmen and one Russian battalion was thought to have light tanks. It was also assumed that there would be elements of German marines and naval personnel in St Malo along with Luftwaffe anti-aircraft troops at Dinard. Flak was thought to be light except in the vicinity of Dinard airfield and port and coastal defences were believed to be light except around Dinard, St Malo and the islands. St Malo and Dinard had been organised for all-round defence with concrete strongpoints, anti-tank obstacles and gun batteries with linking fields of fire. Like Antwerp later in 1944 the port at St Malo would not have been usable unless the mouth of the river was held on both sides and Dinard and St Malo were captured.

1st Airborne Division Operation Instruction for Beneficiary was issued on 28 June and a Planning Intelligence Summary the next day.7 1st Parachute Brigade would land on DZs A and F and would take and hold the town and port of St Malo north of the railway line. After being relieved by 4th Parachute Brigade they would then move eastwards to ‘mop up’ coastal defences north of the St Malo-Cancale road. 4th Parachute Brigade would land on DZs X and E. They would take and hold the port and town south of the railway lines and then take over the whole of the town while 1st Brigade cleared the coastal defences. 1st Airlanding Brigade would land on LZs L, N and Y and would take up a covering position to the south and east of St Malo. Battalions and companies would be detached for specific tasks including the capture of road junctions and high ground, and clearing the landing zones. Divisional troops would land on LZ Y and Hamilcar gliders on LZ Z. With a Landing Zone on the beach transport routes inland were carefully planned with four routes designated towards concentration areas. Traffic would have to be controlled carefully and beach exits might have required clearing by engineers. The Intelligence Summary gave detailed information of German defences in the St Malo area, many of them identified by the interpretation of aerial photographs. Airborne units would also receive substantial mapping and traces. This is the last mention of Beneficiary in the division’s war diary.

SHAEF planning staff held a conference on 29 June and the next day issued a paper considering the logistical implications of airborne operations in Brittany, including Beneficiary.8 The SHAEF staff were concerned that as Beneficiary would require the capture of both sides of the Rance Estuary the airborne forces would be divided and exposed to defeat in detail. In addition coast defences would have to be captured before seaborne landings could take place. The paper concluded that Beneficiary was likely to succeed only if the present garrison in the St Malo area was substantially reduced.

At the time of planning Beneficiary work was also being done to plan for two other operations, Lucky Strike and Hands Up.9 21st Army Group drew up staff studies for Beneficiary and Lucky Strike on 1 and 2 July respectively. A draft outline for Beneficiary was completed on 2 July and shared with First US Army Group on 4 July. A conference on beach reconnaissance for Beneficiary would be held at HQ Airborne Troops on 5 July, with planning teams from 1st Airborne Division and 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment arriving at Moor Park the same day. Details would be tied up with XX US Corps the same day. Planning for Beneficiary was to be completed by the morning of 6 July, while similar processes were taking place concurrently for Hands Up and Lucky Strike.

The airborne planning process sheds light on an aspect of these operations that is often misunderstood. Whilst it is often thought that for every operation thousands of troops boarded aircraft and gliders only to be stood down, this only happened in a small number of cases. A sizeable proportion of the operations did not reach below the divisional level. Perhaps the greatest strain was on the planning staffs, who in early July were planning several tri-service operations concurrently and working with multiple headquarters and formations spread between the UK and the Continent. In early July the planning itself was becoming so congested that the process was scheduled as if it was an operation in itself.

On 6 July Eisenhower sent a memorandum to Bedell Smith.10 Eisenhower limited airborne operations to the equivalent of a reinforced division until transport aircraft could return from assisting with Anvil in the south of France:

A basic feature of anticipated operations in northwest France has been the employment of a large, concentrated airborne force. Due to the delay in returning the original three airborne divisions to England, and the fact that 384 of our transport aircraft must go to the Mediterranean by the end of the current month, it would be impossible to do any really large scale operations here before September. However, I do not want to abandon this concept and desire that planning proceed, involving every likely objective for such an operation.

The situation in the Brittany peninsula and the shortage of transport aircraft led Eisenhower to re-consider Beneficiary and order his staff to resurrect the operation with a target date of 4 to 8 August.

The US Army had established Base Sections to organise troops and supplies, and the Base Section No. 1 plan for Beneficiary was issued on 6 July.11 The Base Section would land across the beaches and restore the port facilities in St Malo, provide service forces and coordinate the phasing-in of supplies. Beneficiary would require the return of an Engineer Shore Brigade from Normandy to Britain with a minimum of 20 days’ preparation before the operation. An advance party of 372 Base Section troops would land on D-Day, before the Base Section headquarters would come ashore at St Malo on D+3. It would take 12 days to get the port facilities into operation both there and at Dinard, while XX Corps would support their own troops over the assault beaches assisted by the Engineer Shore Brigade. The Base Section planned to have 20,311 troops ashore by D+22. A 400-bed Field Hospital would be established in St Malo by D+6 followed by a General Hospital at Dol later. Areas had already been identified for fuel, medical and engineer supply dumps.

The Engineer Plan assumed that the port would be captured on D-Day. Engineer reconnaissance elements would land on D+1 followed by the main party of engineers on D+3. It was planned that the port would eventually handle 2,000 tons per day by D+60. The aim was to handle cargo by lighters and small coasters. Fourteen lighter berths would be constructed and a floating berth for coasters, while beach exits would be constructed to allow DUKWs to unload supplies over the beaches. The Base Section would include three Engineer General Service Regiments, three Engineer Dump Truck Companies, a firefighting platoon, the British dredger Mudeford, an Engineer Port Repair Ship, an Engineer Construction Battalion, an Engineer Maintenance Company, an Engineer Gasoline General Unit and an Engineer Depot Company.

St Malo was a substantial port. It had four large basins, each accessed via locks. Sites had already been identified for a fuel installation, a tank park, supply dump areas, lighterage pierheads and a floating coaster dock. It was predicted that the port facilities at St Malo would probably be damaged by demolitions, including the locks and gates. It was estimated that 90 per cent of the quays would probably be unusable, and that craft would be sunk alongside and in the channels. This reflected the kind of damage that was found when Cherbourg was liberated.

The period from D+1 to D+10 would be spent on site reconnaissance and the preparation of a detailed construction plan, while engineers would construct beach exits and ramps on the assault beaches. By D+20 it was hoped to have eight lighterage pierheads completed outside of the locked basins and by D+30 a 600ft floating berth for small coasters. The water supply and electrical systems would be repaired by D+30. The lock basins would be cleared by D+40 and six lighterage berths would be completed in the Vauban basin. It was hoped that the port would be operating at full capacity by D+60. A recce party of five officers and 20 men from the 1057th Port Construction Group would land on the beaches on D+1, consisting of two companies from the 378th Regiment and the 373rd Engineer General Service Regiment. The Base Section also planned a significant road construction programme. In total 96 miles of roads would be built by D+30, at a rate of six miles per day. It was assumed that 75 to 100 per cent of the bridges in the area would be destroyed along with up to 90 per cent of the culverts. Forty miles of railway track would also be laid from St Malo to Pontaubault, south of Avranches. This line would be completed by D+46 and would involve the reconstruction of up to thirty-six bridges.

The Base Section’s Quartermaster Plan called for a 250,000ft2 General Storage area on the eastern outskirts of the town by D+10 and an eight acre fuel storage area to the south east with a capacity of 2,000 tons by D+8. Other quartermaster units in the port area would include a bakery company, five service companies, two gasoline supply companies, two railhead companies, four quartermaster battalions, a sterilisation company, a grave registration company, two laundry platoons and a petrol production laboratory.

The Base Section’s Transport Plan would see a detachment from the 12th Major Port (Overseas) take over the running of St Malo and the beaches from D+3. Liberty ships would anchor in the open roadstead and be discharged into lighters and barges or beached at high tide. The 12th Major Port included three Port Battalions, nine Port Companies, a Harbour Craft Company, a Port Maritime Maintenance Company, two firefighting platoons, two Quartermaster Truck Companies and an Amphibian Truck Company. The Base Section’s Provost Marshal would have the 79th Military Police Battalion under command. A 150,000ft2 open-air prisoner of war cage would be set up by D+15 with a capacity for 1,000 prisoners.

From D-Day until D+15 medical casualties would be handled by XX Corps. From D+15 any casualties who would not return to duty within seven days would be evacuated to the UK. From D+5 the 49th Field Hospital would be in St Malo with three surgical teams. The 95th General Hospital would be in the Dol region from D+15, and would have 400 beds by D+22 and 1,000 beds by D+27. There would also be a Medical Ambulance Company, a Medical Depot Company and a Lines of Communications Blood Depot Group. All personnel would be immunised against smallpox, typhoid, typhus and tetanus. The Base Section’s medical staff predicted that venereal disease would be prevalent and all medical units were to set up prophylactic stations, with extra stations set up as troop numbers increased. Troops would be briefed to make use of ‘mechanical prophylactics’ and V-packets.

The HQ Airborne Troops plan for Beneficiary was not issued until 7 July, during the initial window in which it was hoped that Beneficiary might take place.12 The delay was presumably due to slower than expected progress in breaking out of the Normandy beachhead to the extent that the provisional date for launching Beneficiary was moved to 1 August. The plan envisaged that the 5th Parachute Division was likely to move east towards Avranches to meet the advance of Allied forces from the Normandy area and that it was also possible that the 319th Infantry Division that was garrisoning the Channel Islands could be evacuated via St Malo, and hence strengthen the German forces in Brittany.

Browning would command all airborne troops during the airborne phase of the operation, but the commander of XX US Corps would assume command of all troops once his headquarters had been established ashore. Urquhart would command all troops east of the Rance – airborne and seaborne – until XX Corps arrived, while the commander of 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment would do likewise for all troops west of the Rance until the US 28th Division arrived. In the context of Allied relations with the Polish Parachute Brigade it is interesting that Major General Sosabowski was to be placed under the command of a colonel commanding a US Parachute Infantry Regiment. It is also interesting to contemplate how Browning would have commanded his forces which would be divided by the Rance. It could well be considered that a corps headquarters was not necessary for the carrying out of the airborne operation.

Dinard airfield was not to be captured immediately, but within 24 hours of the seaborne landing to enable reinforcement by air if the seaborne reinforcements were delayed by bad weather. This proscription does seem remarkably similar to Browning’s orders to General Gavin during Market Garden to not prioritise the capture of the bridge at Nijmegen, which resulted in it having to be captured several days later in conjunction with the relief forces.

The planned use of SAS troops in Beneficiary showed imagination in the use of special forces that was not always present in other airborne operations. One SAS squadron would drop twenty-five small parties in the general area of Dol, Fontorbon, St Aubin, Montauban, Placort and Dinan to disrupt enemy reserves. The SAS were to be prepared to operate for six to seven days, after which they would withdraw into the bridgehead or contact the 4th French Parachute Battalion in area.

Upon landing the first wave of seaborne forces would come under command of the airborne units. 1st Airborne Division and 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment would each take under command one Infantry Regiment from the US 28th Division, one DD tank battalion, one tank destroyer company, two 105mm field artillery battalions and one of 155mm field artillery.

It was still intended to drop some glider troops on the beaches. The orders stated that the exact times for landings would be dependent on the state of moon and tide as the main landing zone was below the high-water mark. The parachute drops would take place soon after darkness, followed by glider landings. Given the fiasco in Sicily when many gliders were cast off into the sea it is hard not to foresee that dropping gliders on a beach landing zone below the tide line could have been fraught with problems. It appears that Beneficiary declined in priority after HQ Airborne Troops orders were issued, for the war diary does not mention the operation at all after 7 July.

The commander of XX Corps, Major General Walton H. Walker, sent his plan for Beneficiary to Patton on 7 July.13 He predicted that stormy weather, high tides, offshore obstacles and the rugged coastline would limit the options for landing over the Brittany beaches. Walker argued that the available beaches were widely separated, small and unfavourable for opposed landings. To have a reasonable chance of success, Walker argued, obstacles on the assault beaches would need to be cleared by the airborne troops before the seaborne landings. Even then, Walker thought that delays in landing seaborne troops might subject the airborne forces to defeat in detail. The navy had also estimated that it would take a considerable time to get St Malo into operation after it had been captured.

The XX Corps plan envisaged the Allied forces in the Neptune area having reached Avranches and Argentan before Beneficiary would be launched. The airborne forces would begin landing between 12 and 48 hours before the seaborne forces. They would clear the beach defences and then ‘initiate action’ to capture St Malo and Dinard as well as the initial beachhead line and begin repairing Dinard airfield. The seaborne forces would land at halfway through a rising tide. Once 28th Division began landing the airborne force would send an airborne element to join the Divisional headquarters.

It was hoped that the airborne forces would be assisted by the French Resistance, who would demolish bridges to isolate the beachhead from German reinforcements but prevent the destruction of the railway bridge over the Rance at Vicomte and the dam at La Quinardais.

The US Army’s Communications Zone – known as COMZ – would land an Engineer Construction Battalion and a reconnaissance force of 200 men to continue clearing the beach defences and to commence work on getting the port at St Malo into service and the 28th Infantry Division would be followed by 80th Infantry Division and 6th Armoured Division. Upon landing 110th Infantry Regiment from 28th Division would come under the command of 1st Airborne Division, but once 80th Infantry Division had landed and passed through, the regiment would revert to their command and assemble around Chateauneuf as a corps reserve.

28th Infantry Division would land with three armoured field artillery battalions equipped with 105mm howitzers, two DD tank battalions, a tank destroyer battalion, one anti-aircraft battalion, a chemical mortar battalion, two engineer construction battalions, a grave registration platoon, six naval shore fire-control parties and two air support parties. The division would land one a two-regiment front with the western regiment over Charlie Red on the Dinard Peninsula and the eastern regiment over Mike Green and Love Green on the Cancale Peninsula. The reserve regiment would land over Dinard but be prepared to switch to the east at short notice. One battalion of the reserve regiment would be prepared to land on Cezembre to neutralise the coastal defence batteries. Divisional headquarters would land on Charlie Red at Dinard and would take command of all troops west of the Rance, whilst 1st Airborne Division would command all troops to the east. Once Dinard had been secured the 504th Regiment and the Polish Brigade would go into corps reserve around Pleslin.

The 80th Infantry Division would have under command a tank battalion, a tank destroyer battalion, an anti-aircraft battalion and two grave registration platoons. It would land with one regiment at Dinard and another at Cancale, with the regiment landing at Dinard coming under the command of 28th Division and divisional headquarters landing at Cancale. The division would concentrate at Limonay and prepare to pass through 1st Airborne Division and occupy the beachhead line east of the Rance. 6th Armoured Division and other corps troops were to be prepared to move to the continent, but their task was not described further. Presumably the armoured division would have had a breakout and exploitation role.

XX Corps directed units on the beachhead line to maintain aggressive patrolling, particularly to the south and south-east. No enemy installations were to be destroyed unless they could not be captured intact. COMZ was to receive priority in St Malo and Dinard after the towns had been captured, to get the port facilities operations.

The Engineer Plan would see three Engineer Combat Battalions landed, with one company on each beach. The assault engineers would deal with the beach obstacles above the tide line at H-Hour, create gaps and mark minefields. They would also breach or bypass obstacles to create two exits from each beach. Each engineer platoon would take along 47 Bangalore torpedoes, 2,470 explosive charges and nine mine detectors. Each assault company would use three 2.5-ton dumper trucks, while the 103rd Engineer Battalion would build roads.

A detailed fire-support plan had been drawn up by XX Corps. It identified the gun batteries on Cezembre and ten emplacements and strongpoints along the coast, including in St Malo itself. Additional targets would be identified as intelligence became available. Naval gunfire would be on call for the seaborne and airborne troops via naval gunfire support parties and air support via air support tentacles.14 Prior to the seaborne and airborne troops linking up the seaborne troops would only call for fire onto targets firing on the beaches, presumably to avoid friendly fire.

H-Hour would see the 2nd Battalion of 110th Infantry Regiment landing on Beach 379 (Mike Green), the 3rd Battalion of the same regiment on Beach 381 (Love Green) and the 1st Battalion of the 190th Infantry Regiment on Beach 399 (Charlie Red). The rest of both regiments would land within 70 minutes, with the advanced divisional command post arriving several hours later. The rest of the division would land over Beach 399 at high tide on D+1. The Tank Destroyer Battalion would arrive on D+2.

28th Infantry Division’s plan for Beneficiary was also issued on 7 July.15 The division would land and secure a beachhead ‘preparatory to further operations’. It was assumed that the 1st Airborne Division would have already cleared the beach obstacles and would have occupied Dinard as well as the initial beachhead line five miles south of St Malo. The division would consist of 13,936 men and 2,227 vehicles along with 7,152 men and 1,770 vehicles attached.

The 109th Infantry Regiment would land on Beach 399 with one battalion in assault formation. After landing they would contact 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment and prepare to advance inland. The 112th Infantry Regiment, minus one battalion, would be in divisional reserve and would land over Beach 399. It would assemble and prepare to advance to either the south or west. The regiment was also to be prepared to land over beaches 379 and 381 if ordered to do so. The regiment’s 1st Battalion would land and capture the Ile de Cezembre with a company of tanks under command.

Aerial reconnaissance would take place of the roads and railways between the Fougeres–Vitre area towards Dinan every three hours from daylight until dusk on D-Day. Coverage would also include the three roads leading south from Dinan to Tinteniac, Becherel and Caulnes. On D-10 the Allied air forces would photograph the area bounded by St Cast, Plancoet, Dol de Bretagne and Pointe du Grouin, including Cezembre, to study changes in defence construction. They would also photograph the defences from St Briac to Cancale at low tide on D-10, D-8 and D-3 including oblique photographs like the beach silhouettes produced of the Normandy coastline before D-Day. At H-3 hours the area around the road to Pleslin and La Giolais would be photographed to check for artillery positions and the concentrations of troops. The whole operational area would be systematically photographed to obtain oblique images, with an emphasis on the road network, likely concentrations of reinforcements and beach defences. Once the Allies had landed the west flank would be reconnoitred by the 28th Reconnaissance Regiment from the River Fremur south to Trelat and provide security for the division’s right flank between Plancoet and Le Guildo.

The 28th Division Intelligence Summary identified two coastal batteries on Cezembre, the 753rd Wach Battalion in St Malo, a Russian battalion on the coast north-west of Cancale and another on the coast west of Dinard, and a naval battalion on the coast west of Dinard. Two battalions of the 5th Parachute Division were in St Malo and Dinard while the rest of the division was at Dinan. It estimated that the first enemy reinforcements would arrive six hours after H-Hour from the Russian coastal battalions. Within 48 hours the Germans would have brought up four infantry divisions, on training division and three Russian battalions.

First US Army Group’s joint plan for Operation Beneficiary was submitted to SHAEF on 8 July 1944.16 The plan had been drawn up in consultation with representatives from Allied Naval Expeditionary Forces, US Ninth Air Forces, HQ Airborne Troops and the Communications Zone and was intended to provide a framework to allow the forces involved to develop their detailed planning. The operation was to be planned under the co-ordination of FUSAG with US Third Army planning the ground and airborne aspects.

The FUSAG plan gave the objective of Beneficiary as the capture a bridgehead around the port of St Malo to facilitate the bringing-in of supplies and additional troops to assist the breakout from the Normandy beachhead towards Avranches and Argentan. The joint plan for Beneficiary was divided into four phases. The first phase would be a preliminary bombardment of the coastal defences and anti-aircraft batteries in the St Malo and Dinard area and the island of Cezembre. The second phase would be an airborne landing to neutralise the beach defences and remove beach obstacles, and to capture the landing beaches. The airborne troops would be assisted by SAS units, Special Forces HQ and the local French Resistance. The third phase would be a seaborne follow-up landing, then the landing of specialist troops and equipment to open the port at St Malo.

The topography and tides of the St Malo area were described as formidable, with severely limited options for landing beaches and drop zones. The plan stated that Beneficiary would only stand a reasonable chance of success if the enemy had no reserves available north of the Loire and west of Rennes, except the ‘skeleton’ forces left to garrison the Brittany coastal defences. The US 28th Division was earmarked for the seaborne assault and was transferred from SHAEF reserve to Third Army. The airborne force would comprise 1st British Airborne Division, the 1st Independent Polish Parachute Brigade, the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment and the 878th Airborne Aviation Engineer Battalion.

Planning for the airborne aspect of Beneficiary was delegated to HQ Airborne Forces. The airborne units were to land prior to the seaborne landings, clear beach defences and obstacles in the St Malo and Dinard area and seize Dinard airfield. The airborne forces would then link up with the seaborne landings and continue to expand the bridgehead until relieved. Charlie Red beach would be at Saint Lunaire west of Dinard, while Love Green and Mike Green would be north of Cancale. The airborne landing and drop zones would be west of Cancale, around Saint Jouain-des-Guerets, south of La Richardais, south west of Pleurtuit, around Le Grand Tourniole and on the beach north of Pont Benoit.

The air plan stated that airborne forces were to be prepared to carry out the operation from 1 August 1944. Their immediate objective would be to clear the landing beaches for the seaborne troops landing 13 hours later. The next objective would be to capture Dinard, St Malo and Dinard airfield. An emergency airfield would be constructed to enable supplies to be brought in by air. The air plan assumed that the airborne operations could take place in either a moon or no-moon period and provided for night-fighter support for the airborne troops in the event of a moonlight period.

The airborne forces would be landed by IX US Troop Carrier Command assisted by 38 and 46 Groups RAF. 1st Airborne Division would drop on the St Malo peninsula to clear beach defences and then assist in the capture of St Malo itself. The US 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment, along with the Polish Brigade, would drop on the Dinard side of the estuary, capture and clear enemy defences, capture the airfield at Dinard and the town itself. SAS troops would be dropped in the south of the St Malo peninsula to disrupt enemy movements.

The FUSAG Joint Plan for Beneficiary was published on 8 July.17 This mission was to ‘Land, assist the seaborne landing by clearing the beach defences and beach obstacles in the St Malo-Dinard area, and seize the initial bridgehead including the Dinard airfield’ and to ‘Continue the operation to expand the bridgehead under command of Third Army Seaborne Task Force commander when he becomes established ashore’. Upon landing and establishing his headquarters the commander of the seaborne task force would assume command of all Allied troops in the bridgehead. The initial beachhead line was to be roughly 5 miles inland from St Malo to the south end of the Rance Estuary, while the final beachhead line was to be 10 miles inland. 28th Division would occupy the western side of the Estuary around Dinard and the 80th Division would hold the area from St Malo to Cancale.

The Joint Plan’s intelligence annex demonstrates how the Allies were able to build a detailed picture of the movements of German units in North West Europe. It predicted that the Germans would have a fighting power equivalent to five divisions to oppose the Allies on the line Avranches–Domfront and that this would eventually reduce to four. It was thought that another four infantry and one of two Panzer divisions may reach the sector by the time the Allies had turned the Avranches corner. Allied intelligence estimated that Brittany was garrisoned by approximately 100,000 German troops. About half of these were formed into divisions with the rest made up of naval coast artillery, assorted infantry, anti-aircraft personnel, Luftwaffe ground personnel, labour and other miscellaneous units. Most of the garrison was either spread along the coast or in the ports. All divisions had sent battlegroups to Normandy.

The coastal defences in the St Malo sector from St Brieuc to Cancale were manned by four or five Russian battalions under 136th Infantry Division, whose headquarters was believed to be at Tressaint. The battalion around the Cancale areas was believed to have several light tanks manned by Russians and Italians. The coastal batteries were manned by naval personnel from the 260th Naval Coast Artillery Battalion. St Malo itself was garrisoned by the 753rd Wach Battalion. The most formidable German formation in the area, the 5th Parachute Division, was also nearby. Although a newly formed division its personnel were thought to be first-class.

The terrain was thought to be favourable for defence. The Rance Estuary was the critical feature of the terrain inland from St Malo. It had an 18-foot tidal range, and a tidal stream of up to eight and a half miles per hour. Inland the country was mainly agricultural and bocage-like, similar to Normandy. The Chief Engineer at ETOUSA – the US Army’s European Theatre of Operations – had identified nine beaches suitable for amphibious landings but suggested that the beaches east of Point du Grouin were sheltered from the prevailing winds, while the beaches to the west were exposed to the north and north-west. The beaches south of Cancale were thought to be suitable for glider landings.

The St Malo defences were described as an incomplete loop with a radius of six miles, made up of tank ditches, roadblocks and strongpoints in the outer perimeter. There were also concrete emplacements at artillery battery positions. The beaches all had underwater obstacles and had been mined, and likely air-landing areas had been obstructed. Long-range coastal guns on the Channel Islands would also limit the sea approaches. The port at St Malo had several locks which were vulnerable to demolition and the narrow approach channels would be easy for the Germans to mine. However, the St Malo garrison was thought to be short of fuel and ammunition, primarily due to problems transporting supplies from the main dumps to the battle area in Normandy.

The FUSAG intelligence assessment concluded that the Germans would defend St Malo and Dinard with the 5th Parachute Division while manning the coastal sector with four or five Russian battalions, including several French light tanks. It was thought that the Germans would probably reinforce the St Malo area with elements of the 319th Infantry Division from the Channels Islands before Beneficiary started and that once the Allies were approaching Avranches they might reinforce Brittany with two or three divisions from Normandy.

In terms of the likely German rate of reinforcement it was predicted that by D+1 they would have reinforced Brittany with one division or elements from tactical reserves and strengthen the St Malo and Dinard garrisons with the equivalent of three parachute battalions from Eastern France. By D+2 the St Malo area might be reinforced by the equivalent of two brigades from the 266th and 275th Infantry Divisions on the south-east coast of Brittany. The Germans were also likely to harass the Allied sea lines of communication with the coastal batteries on the Channel Islands, the island of Cezembre and from the Brittany coast, as well as with mines, E-boats and U-boats.

FUSAG did not think that it was likely that the 319th Infantry Division would be withdrawn from the Channel Islands as by remaining there it threatened the sea approaches to Brittany. Avranches was identified as a key point, and it was thought that the Germans would realise that once it had been reached they could be outflanked in Brittany. FUSAG thought that they might look to reinforce Brittany with two or three divisions from France or Belgium. It was anticipated that the Germans would react quickly to an airborne assault, with the whole of the 5th Parachute Division and several of the Russian battalions manning the coast. The Allies also had an incredibly detailed picture of the ammunition and fuel dumps in the area as well as the Germans motor transport and logistics.

The administrative planning would be carried out by FUSAG and would be executed by Third Army, while COMZ would be responsible for mounting the US part of the operation. During the operation all Allied forces would use American supplies. All casualties would be evacuated to the UK by LST and other craft over the beaches until medical facilities were established in the port. Once the port of St Malo was in operation the beaches close to the port would still be used to increase capacity. The allocation of shipping would be made by 21st Army Group from the shipping already allocated for Overlord.

The Ninth Air Force Outline Plan was issued on 9 July.18 The anticipated date of the operation would be dictated by the progress of the land battle in Normandy and by the moon period. Postponements or cancellations would be communicated through AEAF to Ninth Troop Carrier Command and TCCP at Eastcote six hours before H-Hour.

As well as transporting the airborne forces from bases in the UK and the Cotentin Peninsula, Ninth Air Force would also provide close air support and air defence. It would involve eight groups from IX Troop Carrier Command along with 38 and 46 Groups RAF under command, all of XIX Tactical Command reinforced with a wing from IX Air Defence Command, IX Bomber Command, 878th Airborne Aviation Engineer Battalion and detachments from I Air Force Service Command. The air operation would also call on 150 heavy bombers from the Eighth Air Force and RAF units, including night fighters.

The Ninth Air Force plan assumed that the airborne landings would take place at night. Bombers would fly south simultaneously with the airborne convoys and would attack targets in the south of the Cotentin peninsula as a diversion as well as dropping Window to confuse enemy radar. German radar would be jammed with Mandrel and Airborne Cigar, electronic countermeasures systems, which would be timed to coincide with the airborne convoys. Ninth Air Force would maintain standing patrols of six fighters over the Cotentin peninsula as well as six aircraft to escort the troop carriers. Six sorties would be flown around Rennes to prevent enemy interference from the south and between eight and ten intruder sorties would be flown over German airfields in the area. Four Mosquitos would attack searchlight and flak defences around St Malo shortly after H-Hour. The fire plan would be co-ordinated with Allied Naval Expeditionary Forces (ANXF) and a Fighter Direction Tender would be used.

The airborne pathfinders would be dropped by twelve Stirlings of 38 Group. At the same time SAS Troops would be dropped by eight Stirlings and five Albermarles in the area south of the St Malo peninsula and would operate against enemy lines of communications, with the code name ‘Sampan’. Thirty minutes later six Horsas would land on LZ ‘L’ carrying one company of the 1st Battalion of the Border Regiment who would overcome the enemy defences at the western end of Cancale beach where the main glider force would land. Simultaneously six Stirlings from 38 Group would drop paratroops at Pont Benoit to secure the eastern end of the beach landing area. Fifty minutes after H-Hour 275 C-47s of IX Troop Carrier Command would drop the 1st Parachute Brigade on DZ ‘N’, and the 4th Parachute Brigade on DZ ‘V’. One hour and 30 minutes after H-Hour divisional troops would land on LZ ‘H’, followed half an hour later by 409 Horsas towed by IX Troop Carrier Command C-47s carrying the 1st Airlanding Brigade to LZs ‘A’ and ‘T’. Six Horsas and 28 Hamilcars would land on LZ ‘W’. Once Dinard airfield had been captured 135 Wacos, towed by C-47s of IX Troop Carrier Command, and six Hamilcars towed by 38 Group Halifaxes would land.

XIX Tactical Air Command would provide two flights of fighter aircraft over the beach areas, a squadron of fighters for continuous cover over the naval convoy and four groups of fighter-bombers on ground alert to attack pre-identified targets. It would also provide fighter escort for Ninth Air Force bombers. IX Bomber Command would provide eleven groups of medium and light bombers for attacks on targets identified in the fire plan, at a level of one group per battery. Any attacks requiring fragmentation bombs would be passed on to Eighth Air Force’s heavy bombers. If required second sorties could be launched on targets, with a turnaround time of six hours.

Ninth Air Force’s Intelligence Summary suggested that weaknesses identified in the enemy during the Battle of Normandy were becoming increasingly acute, and that ‘. . . all indications point to the decline of the Nazi Military Regime’. The Luftwaffe were thought to have a total of 685 aircraft in North West Europe, including 440 fighters. Air opposition was therefore expected to be negligible.

The Naval Fire Support Plan was issued on 8 July.19 It would provide naval fire support for the airborne and seaborne forces, neutralise the coast defences on Cezembre and then support the advance inland. The bombarding force would consist of two battleships, two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and six destroyers. A further support group would consist of six Landing Craft Gun (Large), six Landing Craft Tank (Rocket), six Landing Craft Support (Large), eight Landing Craft Tank (Armoured) and six Landing Craft Flak. LCS(S) would precede the leading assault waves. The LCG(L) would accompany the leading waves on the flanks, while the LCT(R) would fire from 3,000 yards offshore.

Four Forward Observer Groups would be provided to control naval gunfire, each consisting of one officer and two men. Two naval liaison groups of one naval officer and five men would be attached to the 1st Airborne Division. The target list attached to the Naval Plan was exhaustive and included grid references for no less than eighteen gun batteries, forty-three emplacements, pillboxes, infantry positions and six minefields.

Despite this extensive planning Beneficiary seems to have slipped in importance, although Montgomery’s directive M510 on 10 July again mentioned St Malo. Montgomery stressed the importance of gaining possession of the Brittany peninsula from an administrative point of view – he described it as ‘essential’. However, Montgomery also went on to say that he would prefer capturing Quiberon Bay to St Malo: ‘I do not want to have to use these [airborne] troops for an operation against St Malo; I prefer to take St Malo from the land . . . these troops will then be available for the operation of seizing the Vannes area, and subsequently of operating to secure Quiberon Bay, or L’Orient.’20

On the same day Richardson at 21st Army Group wrote to Browning and informed him that a reconnaissance could not be carried out of the beaches planned to be used for Beneficiary, as given the relative importance of the operation the risks could not be justified.21

On 12 July Major General Bull wrote to Bedell Smith in response to Eisenhower’s memorandum of 6 July.22 Bull explained that the plan for Beneficiary had been drawn up by FUSAG under the direction of 21st Army Group. Bull felt that with the airborne forces available the capture of each shore of the estuary and the elimination of coastal guns, including on islands, would be a difficult task. While conducting this operation a substantial perimeter would have to be held to enable sea and air reinforcement. The landing of seaborne reinforcements would be hazardous owing to tidal conditions, numerous off-lying rocks and the risk of mines. Even after capture of St Malo movement through the port was likely to be unpredictable due to the narrow approaches. Bull concluded: ‘For the above reasons, it would seem that this operation would be exceedingly difficult and not one which would justify the use of our limited airborne effort.’

Although it would seem that the tide was turning on Beneficiary, Montgomery was still stressing the importance of the Brittany ports. On 21 July he wrote to Simpson at the War Office: ‘But we must get Brittany and the ports in that area. So the next thing must be “the swing” of the western flank, and I shall put everything I can in to getting it going. If we do not get the Brittany ports we cannot develop our full potential.’23

After Brittany had been captured the US Army carried out a detailed study of beach defences in the peninsula including at St Malo and Dinard.24 St Malo beach itself was defended with barbed wire and tetrahedron obstacles, placed in two rows and some with mines fixed to the top. These obstacles had been placed so that they would be 1.5m below water level at high water. Further out was an unidentified new type of steel obstacle, and further still a row of steel hedgehogs. It was thought that further out there would probably be posts with mines. The sea wall at the top of the beach was almost 3ft high and topped with a barbed-wire fence. The Germans had also blocked the entrance to the harbour with a boom.

Across the Rance Estuary at Dinard the obstacles were made mainly of wood and included sawhorse ramps and posts, both with mines attached. They extended out to the low-water mark. Although the beach was small it was enfiladed by cliffs and easily defended. All beach exits were defended by anti-tank walls with elaborate barbed wire obstacles. The entire shoreline was backed by gun emplacements and flamethrowers had been set into the defences with the ability to be fired remotely. Some of them had been placed so that their flames would detonate pre-positioned naval shells.

Both St Malo and Dinard were also well organised for defence from the landward side. Anti-tank roadblocks had been used widely and an anti-tank ditch 15ft wide and 10ft deep ran about two miles inland. Several flooded areas were defended with obstacles, including upright sections of railway track.

It is hard to escape the conclusion that it would have been very challenging for the airborne engineers to clear the beach obstacles sufficiently before the seaborne assault took place. Indeed, the engineer units who landed to clear obstacles on the Normandy beaches on D-Day had been trained and equipped specifically for this task. Whilst the Royal Engineers have always prided themselves on an ability to take on challenges, the lightly-equipped airborne sappers would have been up against it.

Operation Beneficiary was one of the most complex and detailed plans drawn up between D-Day and Operation Market Garden. A tri-service operation aimed at capturing a heavily defended port, it also included a substantial amphibious landing. It demonstrates the numerous factors that came into play in planning airborne operations as part of broader strategy. Urquhart was certainly happy about its cancellation, feeling that St Malo was too strongly defended.25

Beneficiary was very much the first in a series of operations planned to capture the defended ports in Brittany. It was also the first truly inter-Allied operation to be proposed, with a mainly British airborne force supplemented with an American parachute infantry regiment, and then coming under the command of an American corps. It was, in many ways, a scaled-down version of D-Day.