Max Euwe was among the admirers who said the ending in which Fischer excelled was rook and bishop versus rook and knight (Games 35 and 90). But there is another candidate – endings with bishops of opposite color and one pair of rooks. Fischer won some examples of this not-so-rare ending that other grandmasters might have concluded were drawn. His games with Pachman at Havana 1966, Maric at Skopje 1967, Hort at Palma 1970, and Parma at Rovinj-Zagreb 1970 are memorable. But the following is the most impressive of the lot.

Fischer – Győző Forintos

Monte Carlo 1967

Ruy Lopez, Breyer Variation (C95)

1 |

e4 |

e5 |

2 |

♘f3 |

♘c6 |

3 |

♗b5 |

a6 |

4 |

♗a4 |

♘f6 |

5 |

0-0 |

♗e7 |

6 |

♖e1 |

b5 |

7 |

♗b3 |

d6 |

8 |

c3 |

0-0 |

9 |

h3 |

♘b8 |

10 |

d4 |

♘bd7 |

11 |

♘h4 |

|

This gambit (11...♘xe4 12 ♘f5) was popular from about 1961 to 1967, then disappeared for no compelling reason.

11 |

... |

exd4 |

12 |

cxd4 |

♘b6 |

13 |

♘d2 |

|

The offer still holds (13...♘xe4 14 ♘xe4 ♗xh4 15 ♕h5). But Fischer later switched to 13 ♘f3 and obtained a big positional edge against Barczay at Sousse following 13...d5? (13...c5!) 14 e5 ♘e4 15 ♘bd2 ♘xd2 16 ♗xd2 ♗f5 17 ♗c3.

13 |

... |

♘fd5? |

Superior was 13...c5 with pressure on e4 after 14 ♗c2 cxd4 15 ♘hf3 ♖e8 and ...♗b7.

14 |

♘hf3 |

♘b4 |

15 |

d5! |

|

The position has transposed into a variation usually reached via 9...♘d7 10 d4 ♘b6 11 ♘bd2 exd4 12 cxd4 ♘b4 13 d5. White’s move lays claim to c6 for a knight, e.g. 15...♗f6 14 ♘f1 a5 15 a3 ♘a6 16 ♗c2 and 17 ♘d4.

15 |

... |

c5 |

Also good is 15...♘d3 16 ♖e2 ♗f6 and ...♘xc1.

16 |

dxc6 |

♘xc6 |

17 |

♘f1 |

♗f6? |

Black should drive the bishop off b3 first (17...♘a5).

18 |

♗e3! |

|

White needn’t spend a tempo on 18 ♖b1 because he wins material with 18...♗xb2? 19 ♕c2! (an idea not available after 17...♘a5 18 ♗c2 ♗f6). For example, 19...♗xa1 20 ♕xc6 or 19...♘c4 20 ♗xc4 ♗xa1 21 ♗b3 ♘b4 22 ♕d2.

18 |

... |

♘a5 |

19 |

♗d4! |

♗b7 |

The difference between the knights on f1 and b6 is illustrated by 19...♘xb3 20 axb3! ♗b7 21 ♘g3 ♖e8 22 ♘h5, e.g. 22...♖xe4? 23 ♖xe4 ♗xe4 24 ♗xf6 gxf6 25 ♕d4.

20 |

♘g3 |

♘bc4 |

21 |

♗xc4 |

♘xc4 |

22 |

♘h5 |

♘e5 |

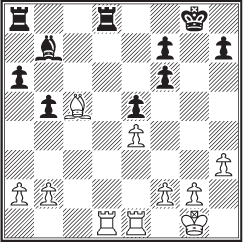

This accepts an inferior endgame – but one with bishops of opposite color – and that explains its appeal compared with the difficult middlegame of 22...♗xd4 23 ♕xd4 f6 24 ♘f4.

23 |

♘xe5 |

dxe5 |

24 |

♗c5 |

♕xd1 |

Worse was 24...♖e8 25 ♕g4 and ♖ad1 – and 24...♗e7? (25 ♕xd8) is a blunder.

25 |

♖axd1 |

♖fd8 |

26 |

♘xf6+ |

gxf6 |

Once he became a grandmaster Fischer played remarkably few pure bishops-of-opposite color endings: He won a pawn-up ending with the infamous bishops against Angelo Sandrin in 1957. He drew three equal-material endings of various lengths with Reshevsky early in his career. And he saved one dead-lost ending, two pawns down, against Edgar Walther at Zürich 1959. But after that he avoided the ending or drew quickly as soon as only bishops and pawns were left.

Yet with heavy pieces on the board, the winning chances increase significantly. A pair of rooks or queens add, for example, the wild card factor of a mating threat, as in Game 95. Also, a rook can be used to break the blockade of pawns or even with an Exchange sacrifice to create a passed pawn.

27 |

♖xd8+ |

♖xd8 |

28 |

♗e7 |

♖d4 |

After 28...♖d2? 29 ♖e3! the mate threat (♖g3+ and ♗xf6) wins a pawn, e.g. 29...h5 30 ♗xf6 ♖xb2 31 a3.

29 |

♖e3! |

♗xe4 |

30 |

♗xf6 |

♔f8 |

Or 30...♗d5 31 ♖xe5 ♖d1+ 32 ♔h2.

31 |

a3 |

♗c6 |

Black had nothing better in view of 32 f3.

32 |

♖xe5 |

♖d5 |

33 |

♖e3 |

|

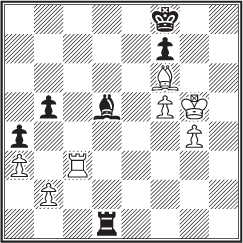

Of course, 33 ♖xd5? gives away almost all of White’s chances. Now he prepares to bring his king to g5, shielded by pawns at f5 and g4. Note that Black has no way of getting his rook to a good square such as e6 that would allow his king to flee the first rank. And 33...♖d6?? loses to 34 ♗e7+.

33 |

... |

♖f5? |

The rook is clumsy here. Better 33...h5 34 f3 ♔g8 and ...♔h7-g6.

34 |

♗e5! |

h5 |

35 |

f3 |

a5 |

♔f2 |

a4 |

Black takes the normal precautions on both wings.

37 |

g4 |

hxg4 |

38 |

hxg4 |

♖g5 |

39 |

♗f6! |

|

A powerful move that revives the idea of mate.

39 |

... |

♖d5 |

Not 39...♖g6? 40 g5 and Black must play the rest of the game without king or rook.

40 |

f4 |

♖d2+ |

41 |

♔g3 |

♖g2+ |

42 |

♔h4 |

♖d2 |

43 |

f5 |

♗d5 |

44 |

♔g5 |

♖d1 |

Despite a bit of his sloppiness, Black’s position looks solid: His pawns are easily protected and 45 ♖h3 (which would have won after 44...♗c4) means nothing after 45...♔e8.

45 |

♖c3! |

|

45 |

... |

♖e1? |

Black also perishes quickly with 45...♗c4? 46 ♖h3 ♔e8 47 ♖h8+ ♔d7 48 ♖d8+ and ♖xd1. But even on 45...♔e8 Black loses a pawn to 46 ♖c5. Then the win isn’t easy but 46...♔d7 47 ♖xb5 ♔c6 48 ♖b4 ♗b3 49 ♔h6 followed by ♔g7 and g4-g5-g6 – or an Exchange sacrifice on f7– will suffice.

46 |

♖h3! |

|

Not 46 ♖d3 ♗c4 47 ♖d8+ ♖e8.

46 |

... |

♔e8 |

47 |

♖d3! |

Resigns |

The bishop can’t move because of 48 ♖d8 mate. Black would also lose after 46...♖h1 47 ♖d3 ♗c6 48 ♖d8+ ♗e8 49 ♖b8 followed by ♗c3-b4+.