But nothing in Fischer’s past prepared fans for the circus that preceded the 1972 world championship match. Would he go to Reykjavik, or wouldn’t he? Did he really offer to play the match for no prize money? And why did he apologize to Spassky as the Russians demanded? When reporters wondered at his behavior, Robert Byrne shrugged it off. “I won’t worry until I see him make a crazy move at the board. Then I’ll know we’ve finally lost him.” That was before 11...♘h5.

Boris Spassky – Fischer

Third game, World Championship match Reykjavik 1972

Modern Benoni Defense (A77)

1 |

d4 |

♘f6 |

2 |

c4 |

e6 |

3 |

♘f3 |

c5 |

4 |

d5 |

exd5 |

5 |

cxd5 |

d6 |

6 |

♘c3 |

g6 |

7 |

♘d2 |

♘bd7 |

8 |

e4 |

♗g7 |

9 |

♗e2 |

0-0 |

10 |

0-0 |

♖e8 |

11 |

♕c2 |

|

11 |

... |

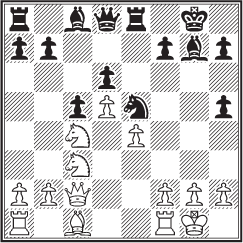

♘h5!?! |

The move left the grandmasters in the press room dumbfounded. “A canvass among the spectators showed a remarkably uniform division of opinion: every average player thought Fischer must have gone a bit mad,” said Chess magazine. “Every grandmaster (Gligorić, Byrne, Krogius, Geller) considered it fascinatingly interesting.” But Ed Edmondson, Fischer’s U.S. Chess Federation protector/father-figure, pronounced it the decisive move of the match. “Spassky is already beaten, defeated by the 11th move in the third game.”

Actually, the idea of allowing Black’s kingside to be wrecked by ...♘h5/♗xh5 occurred in similar form in Timman – Ljubojević from Wijk aan Zee earlier in 1972. But Fischer’s version, with 12...f5 in mind, is more dynamic.

In any case, today’s grandmasters prefer 12...♘e5 13 a4 a6.

12 |

♗xh5 |

|

Too dangerous is 12 f4 ♗d4+ 13 ♔h1 ♕h4 14 ♖f3 ♘df6.

12 |

... |

gxh5 |

13 |

♘c4 |

♘e5 |

After a slightly different move order, 11 a4 ♘e5 12 ♕c2 ♘h5 13 ♗xh5 gxh5, the game Gligorić – Kavalek, played a few weeks later, showed the perils Black is accepting. White’s 14 ♘d1! enabled him to keep a knight on c4 and he held a substantial edge after 14...♕h4 15 ♘e3 ♘g4 16 ♘xg4 hxg4 17 ♘c4.

14 |

♘e3 |

|

This move and the 25 minutes he took to choose 12 ♗xh5 showed that Spassky wasn’t mentally prepared for Fischer. After 14 ♘xe5 ♗xe5, Shakhmaty v SSSR recommended 15 f4 ♗d4+ 16 ♔h1 and, if 16...f5, then 17 e5 dxe5 18 fxe5 ♗xe5 19 ♗f4 “with a strong initiative for White.” But 16...♗d7 is OK.

Also critical is 15 ♗e3, since 15...f5 16 f4! ♗xc3 17 ♕xc3 ♖xe4 leads to a strong dark-square attack after 18 ♖f3 and ♖g3+, as Euwe and Timman pointed out. This is just the kind of sacrifice that fits into Spassky’s style, e.g. 18...h4 19 ♗f2! followed by 20 ♗xh4!. But 19...b5! 20 ♗xh4 ♕xh4 21 ♖h3 b4! barely defends, 22 ♖g3+ ♔f7 23 ♕g7+ ♔e8 24 ♕g8+ ♔d7 25 ♖g7+ ♖e7.

14 |

... |

♕h4! |

15 |

♗d2 |

|

“Feeble” was one of the most generous adjectives used by annotators. White apparently rejected 15 f4 ♘g4 16 ♘xg4 hxg4 17 f5 because of 17...♗e5 18 ♗f4 g3 19 hxg3 ♗d4+, although he has promising compensation after 20 ♖f2 ♕e7 21 g4.

Also better than the text was 15 ♘e2 (or 15 f3) since 15...♘g4 16 ♘xg4 hxg4 17 ♘g3 ♗e5 18 ♗e3 prepares an active plan of 19 f4, or 19 ♕d2 and ♗g5.

15 |

... |

♘g4 |

16 |

♘xg4 |

hxg4 |

Smyslov believed White’s best was to try to set up a good-♘/bad-♗ middlegame with 17 ♘e2! ♗f5 18 ♘g3 ♗g6 19 ♖ae1 h5 20 ♗c3 or 19 ♗c3 ♗xc3 20 bxc3 h5? 21 f4!.

17 |

♗f4 |

♕f6 |

18 |

g3? |

|

White should retreat the bishop to g3 and meet 18...h5 with 19 f3. Or he could play 18 ♕d2 and 19 f3. In either case he has a method of changing the pawn structure that now favors Black.

18 |

... |

♗d7 |

19 |

a4 |

b6 |

This makes the queenside roller of ...a6/...b5 inevitable and leaves White with only one form of counterplay, e4-e5. But that fails for a tactical reason...

20 |

♖fe1 |

a6 |

21 |

♖e2 |

b5! |

...which was 22 axb5 axb5 23 ♖xa8 ♖xa8 24 e5? ♖a1+ 25 ♔g2 dxe5 and now 26 ♗xe5?? allows mate in one, so White is doomed to play out 26 ♖xe5 b4 27 ♘e4 (and 27 ♘b1) ♕a6! or 27 ♘e2 ♕g6!.

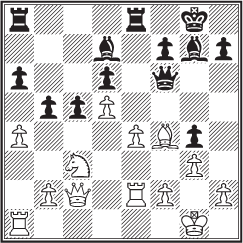

22 |

♖ae1 |

♕g6 |

23 |

b3 |

♖e7 |

Euwe considered this a minor error because it allows White’s counterattack. With 23...♖ac8, he said, Black can push either queenside pawn effectively (24 ♕d3 c4!).

24 |

♕d3 |

♖b8 |

The threat is 25...bxa4 26 bxa4 (26 ♘xa4? ♗b5) ♖b4 or 25...c4 26 bxc4 b4. But Krogius said 24...bxa4 25 bxa4 ♖b8 was better and would have stopped Spassky’s clever defense.

25 |

axb5 |

axb5 |

26 |

b4! |

|

Stopping 26...b4 (with 26...cxb4 27 ♘a2) is a higher priority than granting a passed c-pawn.

26 |

... |

c4 |

27 |

♕d2 |

♖ae8 |

28 |

♖e3 |

h5! |

29 |

♖3e2 |

♔h7 |

30 |

♖e3 |

♔g8 |

31 |

♖3e2 |

♗xc3 |

32 |

♕xc3 |

♖xe4 |

33 |

♖xe4 |

♖xe4 |

34 |

♖xe4 |

|

This actually eases Black’s task, compared with 34 ♖a1 ♖e2 35 ♗e3 or 34...♖e8 35 ♕d4.

34 |

... |

♕xe4 |

Now 35 ♗xd6 allows Black to start threatening mate with 35...♕xd5 and ...♗d7-c6 or ...♕d1+.

The other point is that with the pawn on h7 rather than h5 (as would occur after 28...♗xc3) White could play 35 ♕f6 ♕b1+ 36 ♔g2 ♗f5 37 ♕g5+ ♗g6 38 ♕d8+ ♔g7 39 ♕g5. But with the pawn on h5, Black wins with 38...♔h7! and ...♗e4+.

35 |

♗h6 |

♕g6 |

36 |

♗c1 |

♕b1! |

Black stops 37 ♗b2 and casts a mating net (37 ♔g2? ♗f5).

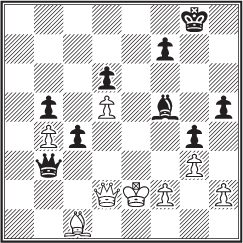

37 |

♔f1 |

♗f5 |

38 |

♔e2 |

♕e4+ |

39 |

♕e3 |

♕c2+ |

40 |

♕d2 |

♕b3! |

Now 41 ♗b2 is verboten because of 41...♕f3+ 42 ♔e1 ♕h1+ and 43...♗d3+.

41 |

♕d4 |

|

Krogius felt 41 ♔e1 and 42 ♗b2 offered chances of resistance (41...c3 42 ♕d4 ♕c2 43 ♗h6). But 42...c2 43 ♗h6 ♕b1+ 44 ♔e2 c1(♘)+! suffices. When play resumed Fischer took several minutes to recheck his analysis of the killer:

41 |

... |

♗d3+! |

White resigns |

||

Decisive: 42 ♔e3 ♕d1! 43 ♕b2 ♕e1+ 44 ♔f4 c3 or 43 ♗b2 ♕f3+.

The alternative, 42 ♔e1 ♕xb4+ 43 ♔d1 ♕b3+ 44 ♔e1 b4 45 ♕e3 ♕b1 and ...c3/...b3-b2 was quite lost.