Author: Unknown

Audience: God’s people

Date: Unknown, though Job himself probably lived during the patriarchal period

Theme: God is active in realms beyond human understanding, even in the midst of great suffering.

Introduction

Author

Although most of the book consists of the words of Job and his friends, Job himself was not the author. We may be sure that the author was an Israelite, since he (not Job or his friends) frequently uses the Israelite covenant name for God (Yahweh; NIV “the LORD”; see article). In the prologue (chs. 1–2), divine discourses (38:1—42:6) and epilogue (42:7–17), “LORD” occurs a total of 25 times, while in the rest of the book (chs. 3–37) it appears only once (12:9).

This unknown author probably had access to a tradition (oral or written) about an ancient righteous man who endured great suffering with remarkable perseverance (Jas 5:11; see note there) and without turning against God (Eze 14:14,20), a tradition the author put to use for his own purposes. While he preserves much of the archaic and non-Israelite flavor in the language of Job and his friends, the author also reveals his own style as a writer of wisdom literature. The book’s profound insights, its literary structures and the quality of its rhetoric all display the author’s genius.

Date

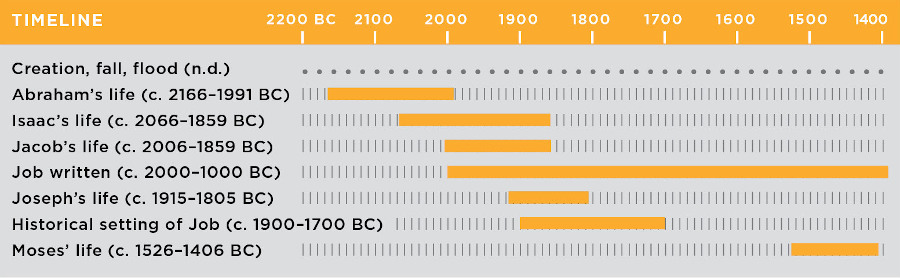

![]() Two dates are involved: (1) that of Job himself and (2) that of the composition of the book. The latter could be dated anytime from the reign of Solomon to the time of Israel’s exile in Babylonia. Although the author was an Israelite, he mentions nothing of Israel’s history. He had an account of a non-Israelite sage, Job (1:1), who probably lived in the second millennium bc (2000–1000). Like the Hebrew patriarchs, Job lived more than 100 years (42:16). Like them, his wealth was measured in livestock and servants (1:3), and like them he acted as priest for his family (1:5). The raiding of Sabean (1:15) and Chaldean (1:17) tribes fits the second millennium, as does the mention of the keśiṭah, “a piece of silver,” in 42:11 (Ge 33:19; Jos 24:32).

Two dates are involved: (1) that of Job himself and (2) that of the composition of the book. The latter could be dated anytime from the reign of Solomon to the time of Israel’s exile in Babylonia. Although the author was an Israelite, he mentions nothing of Israel’s history. He had an account of a non-Israelite sage, Job (1:1), who probably lived in the second millennium bc (2000–1000). Like the Hebrew patriarchs, Job lived more than 100 years (42:16). Like them, his wealth was measured in livestock and servants (1:3), and like them he acted as priest for his family (1:5). The raiding of Sabean (1:15) and Chaldean (1:17) tribes fits the second millennium, as does the mention of the keśiṭah, “a piece of silver,” in 42:11 (Ge 33:19; Jos 24:32).

Language and Text

In many places Job is difficult to translate because of its many unusual words and its style. For that reason, modern translations frequently differ widely. Even the pre-Christian translators of Job into Greek (the Septuagint) seem often to have been perplexed. The Septuagint of Job is about 400 lines shorter than the accepted Hebrew text, and it may be that the translators simply omitted lines they did not understand. The early Syriac (Peshitta), Aramaic (Targum) and Latin (Vulgate) translators had similar difficulties.

Setting and Perspective

While it may be that the author intended his book to be a contribution to an ongoing high-level discussion of major theological issues in an exclusive company of learned scholars, it seems more likely that he intended his story to be told to godly sufferers who, like Job, were struggling with the crisis of faith brought on by prolonged, bitter suffering. He seems to sit too close to the suffering—to be more the sympathetic and compassionate pastor than the detached theologian or philosopher. He has heard what the learned theologians of his day have been saying about the ways of God and what brings on suffering, and he lets their voices be heard. And he knows that the godly sufferers of his day have also heard the “wisdom” of the learned and have internalized it as the wisdom of the ages. But he also knows what “miserable” comfort (16:2) that so-called wisdom gives—that it only rubs salt in the wounds and creates a stumbling block for faith. Against that wisdom he has no rational arguments to marshal. But he has a story to tell that challenges it at its very roots and speaks to the struggling faith of the sufferer. In effect he says to the godly sufferer, “Forget the logical arguments spun out by those who sit together at their ease and discuss the ways of God, and forget those voices in your own heart that are little more than echoes of their pronouncements. Let me tell you a story.”

Theological Theme and Message

When good people (namely, those who fear God and shun evil [1:1]) suffer, the human spirit struggles to understand. Throughout recorded history people have asked: If God is almighty and is truly good, how can he allow such an outrage? The way this question has often been put leaves open three possibilities: (1) God is not almighty after all; (2) God is not just; (3) humans are not innocent. In ancient Israel, however, it was indisputable that God is almighty and that he is perfectly just. It was also agreed that no human is pure in his sight. These three assumptions were also fundamental to the theology of Job and his friends. Simple logic then dictated the conclusion: Every person’s suffering is indicative of the measure of their guilt in the eyes of God. Of course, this conclusion rests on another fatally flawed assumption—that human beings can fully understand the ways of God.

But what thus appeared to be theologically self-evident and unassailable in the abstract was often in radical tension with actual human experience. There were those whose godliness was genuine, whose moral character was upright and who had kept themselves from great transgression, but who nonetheless suffered bitterly (see, e.g., Ps 73). In the speeches of Job 3–37, we hear on the one hand the flawless logic but wounding barbs of those who insisted on the traditional theology, and on the other hand the writhing of the soul of the righteous sufferer (see note on 5:27).

The author of the book of Job broke out of the tight, logical mold of the traditional orthodox theology of his day. He saw that it led to a dead end—that it had no way to cope with the suffering of godly people. Instead of logical arguments, he told a story. And in his story he shifted the angle of perspective. All around him, among theologians and common people alike, were those who attempted to solve the “God problem” in the face of human suffering at the expense of humans (they must all deserve what they get). The author of Job, on the other hand, gave encouragement to godly sufferers by showing them that their suffering provided an occasion like no other for exemplifying what true godliness is for human beings.

The author begins by introducing a third party into the equation. The relationship between God and humans is not exclusive and closed. Among God’s creatures there is the great adversary (chs. 1–2). Incapable of contending with God hand to hand, he is bent on frustrating God’s creation enterprise centered on God’s relationship with the creature that bears his image. As tempter he seeks to alienate humans from God (Ge 3; Mt 4:1); as accuser (one of the names by which he is called, śaṭan, means “accuser” or “adversary” [see note on 1:6]) he seeks to alienate God from humans (Zec 3:1; Rev 12:9–10). His all-consuming purpose is to drive a wedge between God and humans to effect an alienation that cannot be reconciled.

When God mentions Job to the accuser and testifies to his righteousness, Satan attempts with one crafty thrust both to assail God’s beloved and to show up God as a fool. He charges that Job’s godliness is merely self-serving; he is righteous only because it pays (see 1:9 and note). If God will only let Satan tempt Job by breaking the link between righteousness and blessing, he will expose this man and all righteous people as the frauds they really are.

The adversary is sure he has found an opening to accomplish his purpose in the very structure of creation. Humans are totally dependent on God for their lives and well-being. That fact can occasion one of humankind’s greatest temptations: to love the gifts rather than the Giver, to try to please God merely for the sake of his benefits, to be “religious” and “good” only because it pays. If he is right—if the godliness of the righteous can be shown to be evil—then a chasm of alienation stands between God and human beings that cannot be bridged. Then even the godliest among them would be shown to be ungodly. God’s whole enterprise in creation and redemption would be shown to be radically flawed, and God can only sweep it all away in awful judgment.

The accusation, once raised, cannot be ignored; it strikes too deeply into the very structure of creation. So God lets the adversary have his way with Job (within specified limits). From this comes Job’s profound anguish, robbed as he is of every sign of God’s favor so that God becomes for him the great enigma. And his righteousness is also assailed on earth through the logic of the traditional theology of his friends. Alone, he agonizes. But he knows in the depths of his heart that his godliness has been authentic and that someday he will be vindicated (13:18; 14:13–17; 16:19; 19:25–27). And in spite of all, though he may curse the day of his birth (ch. 3) and chide God for treating him unjustly (9:28–35), he will not curse God (as his wife, the human nearest his heart, proposed [2:9] and as Satan said he would [see notes on 1:11–12; 2:10; 3:3; 9:2–3]).

So the adversary is silenced, and God’s delight in the godly is vindicated. Robbed of every sign of God’s favor, Job refuses to repudiate his Maker. Godly Job, dependent creature that he is, passes the supreme test occasioned by his creaturely condition and the adversary’s accusation.

This first test of Job’s godliness inescapably involves a second that challenges his godliness at a level no less deep than the first. For the test that sprang from Satan’s accusation to be real, Job has to be kept in the dark about what is taking place in God’s council chamber. But Job belongs to a race of creatures endowed with wisdom, understanding and insight (something of their godlikeness) that cannot rest until it knows and understands all it can about the creation and the ways of God. Job’s friends confidently assume that the logic of their theology can account for all of God’s ways (but see Isa 55:8–9). However, Job’s experience makes bitterly clear to him that their “wisdom” cannot fathom the truth of his situation. Yet Job’s wisdom is also at a loss to understand. So when the dialogue between Job and his three “wise” friends finally stalemates, the author introduces a poetic essay on wisdom (ch. 28) that exposes the limits of all human wisdom (see note on 28:1–28). Standing as it does at a major juncture between the dialogue (chs. 3–27) and the final, major speeches (chs. 29–37), this authorial commentary on what has been going on in the stalemated dialogue anticipates God’s final word to Job.

In the end the adversary is silenced. Job’s friends are silenced. Job is silenced. But God is not. And when he speaks, it is to the godly Job that he speaks, resulting in the silence of regret for hasty words in days of suffering and the silence of repose in the ways of the Almighty (38:1—42:6). Furthermore, as his heavenly friend, God hears Job’s intercessions for his associates (42:7–10a) and restores Job’s blessed state (42:10b–17).

In summary, the author’s pastoral word to godly sufferers is that God treasures their righteousness above all else. And Satan knows that if he is to thwart the all-encompassing purpose of God, he must assail the godly righteousness of human beings (see 1:21–22; 2:9–10; 23:8,10; cf. Ge 15:6; Hab 2:4). At stake in the suffering of the truly godly is the outcome of the titanic struggle between the great adversary and God. At the same time the author gently reminds the godly sufferer that true, godly wisdom is to reverently love God more than all his gifts and to trust the wise goodness of God even though his ways are often beyond the power of human wisdom to fathom (again see Isa 55:8–9). So here is presented a profound, but painfully practical, drama that wrestles with the wisdom and justice of the Great King’s rule (a “theodicy”; cf. chart [“Babylonian Theodicy”]).

Righteous sufferers must trust in, acknowledge, serve and submit to the omniscient and omnipotent Sovereign, realizing that some suffering is the result of unseen, spiritual conflicts between the kingdom of God and the kingdom of Satan—between the power of light and the power of darkness (cf. Eph 6:10–18; Col 1:12–13 and notes). Even though God’s people may not always understand why God acts the way he does, they can rest in the assurance of knowing he understands. In the NT, however, Satan’s final defeat is assured after Jesus’ second coming (Rev 20:10), and even Jesus’ first coming results in Satan falling “like lightning from heaven” (Lk 10:18). Consequently, Satan’s power to afflict God’s people is greatly diminished and only temporary (Rev 12:7–17).

Literary Form and Structure

![]() Like some other ancient compositions (cf., e.g., the Code of Hammurapi; see chart), the book of Job has a sandwich literary structure: prologue, main body, and epilogue, revealing a creative composition, not an arbitrary compilation. Furthermore, in Job the prologue and epilogue are prose, while the main body is poetry. Some of Job’s words are lament (cf. ch. 3 and many shorter poems in his speeches), but the form of lament is unique to Job and often unlike the regular format of most lament psalms (except Ps 88). Much of the book takes the form of legal disputation. Although the friends come to console him, they end up arguing over the reason for Job’s suffering. The argument breaks down in ch. 27, and Job then proceeds to make his final appeal to God for vindication (chs. 29–31). The wisdom poem in ch. 28 appears to be the words of the author (not of Job or his friends), who sees the failure of the dispute as evidence of a lack of wisdom.

Like some other ancient compositions (cf., e.g., the Code of Hammurapi; see chart), the book of Job has a sandwich literary structure: prologue, main body, and epilogue, revealing a creative composition, not an arbitrary compilation. Furthermore, in Job the prologue and epilogue are prose, while the main body is poetry. Some of Job’s words are lament (cf. ch. 3 and many shorter poems in his speeches), but the form of lament is unique to Job and often unlike the regular format of most lament psalms (except Ps 88). Much of the book takes the form of legal disputation. Although the friends come to console him, they end up arguing over the reason for Job’s suffering. The argument breaks down in ch. 27, and Job then proceeds to make his final appeal to God for vindication (chs. 29–31). The wisdom poem in ch. 28 appears to be the words of the author (not of Job or his friends), who sees the failure of the dispute as evidence of a lack of wisdom.

So in praise of true wisdom he centers his structural apex between the three cycles of dialogue-dispute (chs. 3–27) and the three monologues: Job’s (chs. 29–31), Elihu’s (chs. 32–37) and God’s (38:1—42:6). Job’s monologue turns directly to God for a legal decision: that he is innocent of the charges his counselors have leveled against him. Elihu’s monologue—another human perspective on why people suffer—rebukes Job but moves beyond the punishment theme to the value of divine chastening and God’s redemptive purpose in it. God’s monologue gives the divine perspective: Job is not condemned, but neither is a logical or legal answer given to why Job has suffered. That remains a mystery to Job, though the readers are ready for Job’s restoration in the epilogue because they have had the heavenly vantage point of the prologue all along. So the literary structure and the theological significance of the book are beautifully tied together.

When good people suffer, the human spirit struggles to understand. Throughout recorded history people have asked: If God is almighty and is truly good, how can he allow such an outrage?

Outline

I. Prologue (chs. 1–2)

A. Job’s Happiness (1:1–5)

B. Job’s Testing (1:6—2:13)

1. Satan’s first accusation (1:6–12)

2. Job’s faith despite loss of family and property (1:13–22)

3. Satan’s second accusation (2:1–6)

4. Job’s faith during personal suffering (2:7–10)

5. The coming of the three friends (2:11–13)

II. Dialogue-Dispute (chs. 3–27)

A. Job’s Opening Lament (ch. 3)

B. First Cycle of Speeches (chs. 4–14)

1. Eliphaz (chs. 4–5)

2. Job’s reply (chs. 6–7)

3. Bildad (ch. 8)

4. Job’s reply (chs. 9–10)

5. Zophar (ch. 11)

6. Job’s reply (chs. 12–14)

C. Second Cycle of Speeches (chs. 15–21)

1. Eliphaz (ch. 15)

2. Job’s reply (chs. 16–17)

3. Bildad (ch. 18)

4. Job’s reply (ch. 19)

5. Zophar (ch. 20)

6. Job’s reply (ch. 21)

D. Third Cycle of Speeches (chs. 22–26)

1. Eliphaz (ch. 22)

2. Job’s reply (chs. 23–24)

3. Bildad (ch. 25)

4. Job’s reply (ch. 26)

E. Job’s Closing Discourse (ch. 27)

III. Interlude on Wisdom (ch. 28)

IV. Monologues (29:1—42:6)

A. Job’s Call for Vindication (chs. 29–31)

1. His past honor and blessing (ch. 29)

2. His present dishonor and suffering (ch. 30)

3. His protestations of innocence and final oath (ch. 31)

B. Elihu’s Speeches (chs. 32–37)

1. Introduction (32:1–5)

2. The speeches themselves (32:6—37:24)

a. First speech (32:6—33:33)

b. Second speech (ch. 34)

c. Third speech (ch. 35)

d. Fourth speech (chs. 36–37)

C. Divine Discourses (38:1—42:6)

1. God’s first discourse (38:1—40:2)

2. Job’s response (40:3–5)

3. God’s second discourse (40:6—41:34)

4. Job’s repentance (42:1–6)

V. Epilogue (42:7–17)

A. God’s Verdict (42:7–9)

B. Job’s Restoration (42:10–17)