Authors: David, Asaph, the Sons of Korah, Solomon, Heman, Ethan, Moses and unknown authors

Audience: God’s people

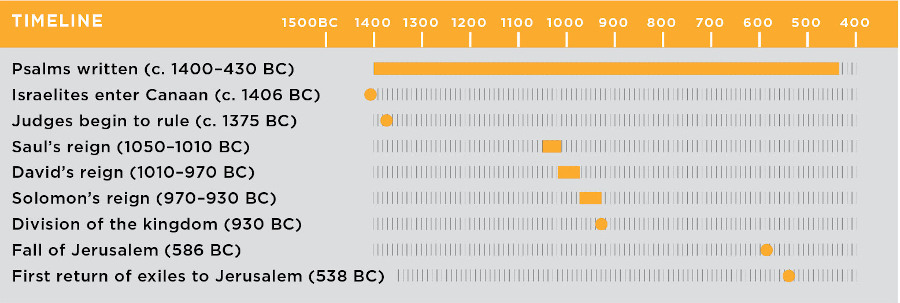

Date: Between the time of Moses (probably about 1440 bc) and the time following the Babylonian exile (after 538 bc)

Theme: God, the Great King, inspires the psalmists’ words of lament and praise that are appropriate responses to God.

Introduction

Title

The titles “Psalms” and “Psalter” come from the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT), where they originally referred to stringed instruments (such as harp, lyre and lute), then to songs sung with their accompaniment. The traditional Hebrew title is tehillim (meaning “praises”; see note on Ps 145 title), even though many of the psalms are tephilloth (meaning “prayers,” including laments). In fact, one of the first collections included in the book is titled “the prayers of David son of Jesse” (72:20).

Collection, Arrangement and Date

The Psalter is a collection of collections and represents the final stage in a process that began in the early days of the first (Solomon’s) temple (or even earlier in the time of David), when the temple liturgy began to take shape. Both the scope of its subject matter and the arrangement of the whole collection strongly suggest that this collection was viewed by its final editors as a guide for the life of faith in accordance with the Law, the Prophets and the Writings. By the first century ad it was referred to as the “Book of Psalms” (Lk 20:42; Ac 1:20). At that time Psalms appears also to have been used as a shorthand designation for the entire section of the Hebrew OT canon more commonly known as the Writings (see Lk 24:44 and note). Many collections preceded this final compilation of the Psalms (e.g., “the prayers of David,” noted above).

Additional collections expressly referred to in the present Psalter titles are: (1) the songs and/or psalms “of the Sons of Korah” (Ps 42–49; 84–85; 87–88), (2) the psalms and/or songs “of Asaph” (Ps 50; 73–83) and (3) the songs “of ascents” (Ps 120–134).

Other evidence points to further compilations. Ps 1–41 (Book I) make frequent use of the divine name Yahweh (“the LORD”), while Ps 42–72 (Book II) make frequent use of Elohim (“God”). Moreover, Ps 93–100 appear to be a traditional collection (see “The LORD reigns” in 93:1; 96:10; 97:1; 99:1). Other apparent groupings include Ps 111–118 (a series of Hallelujah psalms; see introduction to Ps 113–118), Ps 138–145 (each of which include “of David” in their titles) and Ps 146–150 (each of which begins and ends with “Praise the LORD”; see NIV text note on 111:1).

In its final edition, the Psalter contained 150 psalms. On this the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) and Hebrew texts agree, though they arrive at this number differently. The Septuagint has an extra psalm at the end (but not numbered separately as Ps 151); it also unites Ps 9–10 (see NIV text note on Ps 9) and Ps 114–115 and divides Ps 116 and Ps 147 each into two psalms. Both the Septuagint and Hebrew texts number Ps 42–43 as two psalms, though they were evidently originally one (see NIV text note on Ps 42).

In its final form the Psalter was divided into five Books (Book I: Ps 1–41; Book II: 42–72; Book III: 73–89; Book IV: 90–106; Book V: 107–150), each of which was provided with a concluding doxology (see 41:13; 72:18–19; 89:52; 106:48; 150). The first two of these Books were probably preexilic. The division of the remaining psalms into three Books, thus attaining the number five, was possibly in imitation of the five books of Moses. In spite of this five-book division, the Psalter was clearly thought of as a whole, with an introduction (Ps 1–2) and a conclusion (Ps 146–150). Notes throughout the Psalms give additional indications of conscious arrangement.

Authorship and Titles (or Superscriptions)

Of the 150 psalms, only 34 lack superscriptions of any kind (only 17 in the Septuagint, the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT). These psalms are found mainly in Books III—V, where they tend to occur in clusters: Ps 91; 93–97; 99; 104–107; 111–119; 135–137; 146–150. (In Books I—II, only Ps 1–2; 10; 33; 43; 71 lack titles, and Ps 10 and 43 are actually continuations of the preceding psalms.)

The contents of the superscriptions vary but fall into a few broad categories: (1) author, (2) name of collection, (3) type of psalm, (4) musical notations, (5) liturgical notations and (6) brief indications of occasion for composition. For details, see notes on the titles of the various psalms.

There is no consensus on the antiquity and reliability of these superscriptions. That many of them are at least preexilic appears evident from the fact that the Septuagint translators were sometimes unclear as to their meaning. Furthermore, the practice of attaching titles, including the name of the author, is ancient. On the other hand, comparison between the Septuagint and the Hebrew texts shows that the content of some titles was still subject to change well into the postexilic period.

As for the superscriptions regarding historical occasion of composition, many of these brief notations of events read as if they had been taken from 1,2 Samuel. Moreover, they are sometimes not easily correlated with the content of the psalms they head. This suggests they may be later attempts to fit the psalms into the real-life events of history, though the limited number of such notations and apparent mismatches raises some doubt in this regard.

Regarding authorship, opinions are even more divided. The notations themselves are ambiguous since the Hebrew phraseology used, meaning in general “belonging to,” can also be taken in the sense of “concerning” or “for the use of” or “dedicated to.” The name may refer to the title of a collection of psalms that had been gathered under a certain name (as “Of Asaph” or “Of the Sons of Korah”). To complicate matters, there is evidence within the Psalter that at least some of the psalms were subjected to editorial revision in the course of their transmission. As for Davidic authorship, there can be little doubt that the Psalter contains psalms composed by that noted singer and musician and that there was at one time a “Davidic” psalter. This, however, may have also included psalms written concerning David, or concerning one of the later Davidic kings, or even psalms written in the manner of those he authored. It is also true that the tradition as to which psalms are “Davidic” remains somewhat indefinite, and some “Davidic” psalms seem clearly to reflect later situations (see, e.g., Ps 30 title—but see also note there; and see introduction to Ps 69 and note on Ps 122 title). Moreover, “David” is sometimes used elsewhere in the OT as a collective for the kings of his dynasty, and this could also be true in some of the psalm titles.

Psalm Types

Hebrew superscriptions to the Psalms acquaint us with an ancient system of classification: (1) mizmor (“psalm”); (2) shiggaion (possibly a musical term; see note on Ps 7 title); (3) miktam (unknown meaning; see note on Ps 16 title); (4) shir (“song”); (5) maśkil (see note on Ps 32 title); (6) tephillah (“prayer”); (7) tehillah (“praise”); (8) lehazkir (“for being remembered”—i.e., before God, a petition); (9) letodah (“for praising” or “for giving thanks”); (10) lelammed (“for teaching”); and (11) shir yedidoth (“song of loves”—i.e., a wedding song). The meaning of many of these terms, however, is uncertain. In addition, some titles contain two of these (especially mizmor and shir), indicating that the types are diversely based and overlapping.

Analysis of form of content has given rise to three main types (or genres) of psalms: (1) hymns (e.g., Ps 8, 33, 100, 103, 113, 117, 150); (2) laments (e.g., Ps 5–7, 22, 26, 42, 64, 79, 130); and (3) thanksgiving psalms (e.g., Ps 9, 107, 118, 136). While many other types of psalms have been identified (e.g., wisdom, confidence, redemptive-historical, Zion, royal, etc.) they may be considered subsets of these three main types. For example, redemptive-historical psalms like Psalm 107 fit within the larger category of thanksgiving psalms.

Hymns are characterized by exuberant praise to God motivated by specific reasons outlined by the psalmist. Thus, hymns usually contain (1) a call to praise God; (2) reasons for that praise; and (3) often an additional call to praise God.

Laments (perhaps surprisingly the most common type of psalm in the Psalter) are at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum from hymns. Laments are identified by several distinct characteristics, though not all of these are present in every lament: (1) an introductory call to God for help; (2) a description of the problem; (3) a confession of sin or an assertion of trust or innocence; (4) a call to God to deal with the problem; and (5) a declaration of confidence in God’s response and / or commitment to praise him.

Thanksgiving psalms describe the psalmist’s deliverance from some threat and the subsequent commitment to praise God for it. They characteristically contain: (1) a call to praise God that sometimes includes reasons; (2) a description of the threat and what God has done to resolve it; and (3) further praise and / or calls to praise.

As can be seen from the above descriptions, these psalm types are not rigid, and overlap exists. In addition, it is frequently helpful to note whether the psalm originates from or is intended for use by an individual or the larger community. Even here, though, distinctions are difficult inasmuch as an individual (the priest or the king) could be speaking on behalf of the community. Also, the psalm may have had a liturgical use which involved both an individual and the larger community.

Literary Features

The Psalter is poetry from first to last. The psalms are impassioned, vivid and concrete; they are rich in images, in simile and metaphor. Other literary features include assonance, alliteration, wordplays, repetition and the piling up of synonyms. Key words frequently highlight major themes in prayer or song. Inclusio or framing (repetition of a significant word or phrase from the beginning that recurs at the end) frequently wraps up a composition or a unit within it. The notes on the structure of the individual psalms often call attention to literary frames within which the psalm has been set.

Hebrew poetry lacks rhyme and regular meter. Its most distinctive and pervasive feature is parallelism. Most poetic lines are composed of two (sometimes three) balanced segments (the balance is often loose, with the second segment commonly somewhat shorter than the first). The traditional categories of parallelism are synonymous, antithetic, and synthetic. In synonymous parallelism, the same thought is expressed in both segments by means of synonyms. Antithetic parallelism presents a parallel by contrast through the use of antonyms. In synthetic parallelism, the second segment completes the thought of the first segment. Although a traditional classification, synthetic parallelism is not actually parallelism at all and seems to be nothing more than a default category for poetic lines that don’t fit the other two categories. When the second or third segment of a poetic line repeats, echoes or overlaps the content of the preceding segment, it intensifies or more sharply focuses the thought or its expression. In the NIV the second and third segments of a line are slightly indented relative to the first. See chart.

Determining where the Hebrew poetic lines or line segments begin or end (scanning) is sometimes an uncertain matter. Even the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) at times scans the lines differently from the way the Hebrew texts now available to us do. It is therefore not surprising that modern translations occasionally differ.

A related problem is the extremely concise, often elliptical, writing style of the Hebrew poets. The syntactical connection of words must at times be inferred simply from context. Where more than one possibility presents itself, translators are confronted with ambiguity. They are not always sure with which line segment a border word or phrase is to be read.

The stanza structure of Hebrew poetry is also a matter of dispute. Occasionally, recurring refrains mark off stanzas, as in Ps 42–43; 57. In Ps 110 two balanced stanzas are divided by their introductory prophecies (see also introduction to Ps 132), while Ps 119 devotes eight lines to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet. For the most part, however, no such obvious indicators are present. The NIV has used spaces to mark off poetic paragraphs (called “stanzas” in the notes). Usually this could be done with some confidence, and the reader is advised to be guided by them.

The word Selah is found in 39 psalms, all but two of which (Ps 140; 143, both “Davidic”) are in Books I—III. It is also found in Hab 3, a psalm-like poem. Suggestions as to its meaning abound, but honesty must confess ignorance. Most likely it is a liturgical notation. The common suggestion that it calls for a brief musical interlude or for a brief liturgical response by the congregation is plausible but unproven (the former may be supported by the Septuagint rendering). In some instances its present placement in the Hebrew text is highly questionable.

Close study of the Psalms discloses that the authors often composed with an overall design in mind. This is true of the alphabetic acrostics, in which the poet devoted to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet one line segment (as in Ps 111–112), a single line (as in Ps 25; 34; 145), two lines (as in Ps 37) or eight lines (as in Ps 119). In addition, Ps 33; 38; 103 have 22 lines each, no doubt because of the number of letters in the Hebrew alphabet (see Introduction to Lamentations: Literary Features). Although the intended purpose of acrostics remains unknown, constructing a psalm around the alphabet may have facilitated memorization or may simply have been aesthetically pleasing.

Other literary devices were also used. For example, there are psalms that devote the same number of lines to each stanza (e.g., Ps 12; 41), or do so with variation only in the introductory or concluding stanza (e.g., Ps 38; 83; 94). Others match the opening and closing stanzas and balance the ones between (e.g., Ps 33; 86). A particularly interesting device is to place a key thematic line at the very center, sometimes constructing the whole or part of the poem around that center (see note on 6:6). Still other design features are pointed out in the notes. The authors of the psalms crafted their compositions very carefully. They were heirs of an ancient art, and they developed it to a state of high sophistication. Their works are best appreciated when carefully studied and pondered.

Theology

The Psalter is for the most part a book of the laments and praises of God’s people. But there are also psalms that are explicitly instructional in form and purpose, teaching the way of godliness. As noted above (Collection, Arrangement and Date), the manner in which the whole collection has been arranged suggests that one of its main purposes was instruction in the life of faith, a faith formed and nurtured by the Law, the Prophets and the Writings. Accordingly, the Psalter is theologically rich. Its theology is, however, not abstract or systematic but doxological, confessional and practical. Included here are a number of the major themes of the Psalter.

(1) God rules over all. At the core of the theology of the Psalter is the conviction that the gravitational center of life (of right human understanding, trust, hope, service, morality, adoration), but also of history and of the whole creation (heaven and earth), is God (Yahweh, “the LORD”; see Dt 6:4 and note). He is the Great King over all, the One to whom all things are subject. He created all things and preserves them. Because he ordered them, they have a well-defined and true identity. Because he maintains them, they are sustained and kept secure from disruption, confusion or annihilation. Because he alone is the sovereign God, they serve one divine purpose. Under God creation is an orderly and systematic whole. Through creation the Great King’s majestic glory is displayed. He is good (wise, righteous, faithful, amazingly benevolent and merciful—evoking trust), and he is great (his knowledge, thoughts and works are beyond human comprehension—evoking reverent awe). By his good and lordly rule he is shown to be the Holy One.

(2) God tolerates no rivals. As the Great King by right of creation and his enduring, absolute sovereignty, God ultimately will not tolerate any worldly power that opposes, denies or ignores him. He will come to rule the nations so that all will be compelled to acknowledge him. This expectation is no doubt the root and broadest scope of the psalmists’ long view of the future. Because the Lord is the Great King beyond all challenge, his righteous and peaceful kingdom will come, overwhelming all opposition and purging the creation of all rebellion against his rule.

(3) God opposes the proud and exalts the humble. As the Great King on whom all creatures depend, God opposes the proud, those who rely on their own resources to work out their own destiny. These are the ones who ruthlessly wield whatever power they possess to attain worldly wealth, status and security—who are a law to themselves and exploit others as they will. In the Psalter, this kind of pride is the root of all evil. Those who embrace it, though they may seem to prosper, will be brought down to death, their final end. The humble, the poor and needy, those who acknowledge their dependence on the Lord in all things—these are the ones in whom God delights. Hence the “fear of the LORD”—i.e., humble trust in and obedience to the Lord—is the beginning of all wisdom (111:10). Ultimately, those who embrace it will inherit the earth. Not even death can separate them from God.

(4) God is the righteous Judge. Because God is the Great King, he is the ultimate Executor of justice among humans. God is the mighty and faithful Defender of the defenseless and the wronged. He knows every deed and the secrets of every heart. There is no escaping his scrutiny. No false testimony will mislead him in judgment. And he hears the pleas brought to him. As the good and faithful Judge, he delivers those who are oppressed or wrongfully attacked and redresses the wrongs committed against them (see note on 5:10). This is the unwavering conviction that accounts for the psalmists’ impatient complaints when they, as poor and needy, boldly cry to him, “Why, LORD (have you not yet delivered me)?” “How long, LORD (before you act)?”

(5) God chose Israel as his special people. As the Great King over all the earth, the Lord has chosen the Israelites to be his inheritance among the nations. He has delivered them by mighty acts out of the hands of the world powers, has given them a land of their own and has united them with himself in covenant as the initial embodiment of his redeemed kingdom. Thus, both their destiny and his honor came to be bound up with this relationship. To them he also gave his word of revelation, which testified of him, made specific his promises and proclaimed his will. By God’s covenant, Israel was to live among the nations, loyal only to their heavenly King. They were to trust solely in his protection, hope in his promises, live in accordance with his will and worship him exclusively. Israel was to sing his praises to the whole world—which in a special sense revealed their anticipatory role in the evangelization of the nations.

(6) God chose David as king. As the Great King, Israel’s covenant Lord, God chose David to be his royal representative on earth. In this capacity, David was the Lord’s servant. The Lord himself anointed him and adopted him as his royal “son” to rule in his name. Through him God made his people secure in the promised land and subdued all the powers that threatened them. What is more, he covenanted to preserve the Davidic dynasty. Henceforth the kingdom of God on earth, while not dependent on the house of David, was linked to it by God’s decision and commitment. In its continuity and strength lay Israel’s security and hope as they faced a hostile world. And since the Davidic kings were God’s royal representatives in the earth, in concept seated at God’s right hand (110:1), the scope of their rule was potentially worldwide (see Ps 2).

The Lord’s anointed, however, was more than a warrior king. He was to be endowed by God to govern his people with righteousness: to deliver the oppressed, defend the defenseless, suppress the wicked and thus bless the nation with internal peace and prosperity. He was also an intercessor with God on behalf of the nation, the builder and maintainer of the temple and the foremost voice calling the nation to worship the Lord.

(7) God chose Jerusalem as his royal residence. As the Great King, God (who had chosen David and his dynasty to be his royal representatives) also chose Jerusalem (the City of David) as his own royal city, the earthly seat of his throne. Thus Jerusalem became the earthly capital and symbol of the kingdom of God. There in his temple he ruled his people. There his people could meet with him to bring their prayers and praise and to see his power and glory. From there he brought salvation, dispensed blessings and judged the nations. And with him as the city’s great Defender, Jerusalem was the secure citadel of the kingdom of God, the hope and joy of God’s people.

God’s goodwill and faithfulness toward his people were most strikingly symbolized by his pledged presence among them at his temple in Jerusalem, the “city of the Great King” (48:2). But no manifestation of his benevolence was greater than his readiness to forgive the sins of those who humbly confessed them and whose hearts showed him that their repentance and professions of loyalty to him were genuine.

Unquestionably the supreme kingship of Yahweh is the most basic metaphor and most pervasive theological concept in the Psalter—as in the OT generally. It provides the fundamental perspective in which people are to view themselves, the whole creation, events in nature and history, and the future. All creation is Yahweh’s one kingdom. To be a creature in the world is to be a part of his kingdom and under his rule. To be a human being in the world is to be dependent on and responsible to him. To proudly deny that fact is the root of all wickedness.

God’s election of Israel, together with the giving of his word, represents the renewed inbreaking of God’s righteous kingdom into this world of rebellion and evil. It initiates the great divide between the righteous nation and the wicked nations, and on a deeper level between the righteous and the wicked generally, a more significant distinction that cuts even through Israel. In the end this divine enterprise will triumph. Human pride will be humbled, and wrongs will be redressed. The humble will be given the whole earth to possess, and the righteous and peaceful kingdom of God will come to full realization. When the Psalter was being given its final form, what the psalms said about the Lord and his ways with his people, with the nations, with the righteous and the wicked, and what the psalmists said about the Lord’s anointed, his temple and his holy city—all this was understood in light of the prophetic literature (both Former and Latter Prophets). Relative to these matters, the Psalter and the Prophets were mutually reinforcing and interpretive.

When the Psalms speak of the king on David’s throne, they speak of the king who is being crowned (as in Ps 2; 72; 110—though some think 110 is an exception) or is reigning (as in Ps 45) at the time. They proclaim his status as the Lord’s anointed and declare what the Lord will accomplish through him and his dynasty. Thus they also speak of the sons of David to come—and in the exile and the postexilic era, when there was no reigning king, they spoke to Israel only of the great Son of David whom the prophets had announced as the one in whom God’s covenant with David would yet be fulfilled. So it is not surprising that the NT quotes these psalms as testimonies to Christ, which in a unique way they are. In him they are truly fulfilled.

When in the Psalms righteous sufferers cry out to God in their distress (as in Ps 22; 69), they give voice to the sufferings of God’s servants in a hostile and evil world. These cries became the prayers of God’s oppressed people, and as such they were taken up into Israel’s book of prayers. When Christ came in the flesh, he identified himself with God’s humble people in the world. He became for them God’s righteous servant par excellence, and he shared their sufferings at the hands of the wicked. Thus, these prayers became his prayers also. In him the suffering and deliverance of which these prayers speak are fulfilled. At the same time, they continue to be the prayers of those who take up their cross and follow him.

Similarly, in speaking of God’s covenant people, of the city of God and of the temple in which God dwells, the Psalms ultimately speak of Christ’s people, the church. The Psalter is not only the prayer book of the second temple; it is also the enduring prayer book of the people of God across generations. Now, however, Christians pray these prayers in the light of the new era of redemption that dawned with the first coming of the Messiah and that will be consummated at his second coming.

The Psalter is theologically rich. Its theology is, however, not abstract or systematic but doxological, confessional and practical.

Unquestionably the supreme kingship of Yahweh is the most pervasive theological concept in the Psalter. It provides the fundamental perspective in which people are to view themselves, the whole creation, events in nature and history, and the future.

Psalms: Table of Contents

I. Book I (Ps 1–41)

A. Introduction (Ps 1–2)

B. The Only Source of Human Confidence (Ps 3–14)

1. Laments for deliverance (Ps 3–7)

2. The glory of God bestowed on human beings (Ps 8)

3. Laments for deliverance (Ps 9–13)

4. The folly of rejecting God (Ps 14)

C. Human Security in Relationship With God (Ps 15–24)

1. Requirements for access to God (Ps 15)

2. Refuge in God (Ps 16)

3. Vindication from God (Ps 17–18)

4. God’s glory revealed in creation and in the law (Ps 19)

5. Vindication from God (Ps 20–22)

6. Refuge in God (Ps 23)

7. Requirements for access to God (Ps 24)

D. Laments and Divine Responses (Ps 25–33)

1. “Remember, LORD, your great mercy and love” (Ps 25)

2. Lament of one who avoids sin (Ps 26)

3. Confidence in the Lord in the face of enemies (Ps 27)

4. Lament of one going “down to the pit” (Ps 28)

5. The mighty Lord who “blesses his people with peace” (Ps 29)

6. Thanksgiving of one rescued from going “down to the pit” (Ps 30)

7. Lament to the Lord in the face of enemies (Ps 31)

8. Blessedness of one whose sins are forgiven (Ps 32)

9. The Lord remembers “those whose hope is in his unfailing love” (Ps 33)

E. Instruction in Wisdom and Laments Over Wickedness (Ps 34–37)

1. Instruction in godly wisdom (Ps 34)

2. Laments over the wicked (Ps 35–36)

3. Instruction in godly wisdom (Ps 37)

F. Laments to God Ps 38–41

II. Book II (Ps 42–72)

A. Three Laments and a Royal Psalm (Ps 42–45 [see the parallel section Ps 69–72])

B. Hymns Celebrating Zion, the City of God (Ps 46–48)

C. The Proper Posture Before God (Ps 49–53)

1. Trust in God and not oneself (Ps 49)

2. Sincerity and blamelessness (Ps 50)

3. A pure heart and steadfast spirit (Ps 51)

4. Righteousness and faithfulness (Ps 52)

5. The fool rejects these things (Ps 53)

D. Laments Over the Enemies of God and His People (Ps 54–64)

E. Praise and Thanksgiving for God’s Blessing (Ps 65–68)

1. Praise for God’s abundant provision (Ps 65)

2. Thanksgiving for God’s saving acts (Ps 66)

3. Praise for God’s righteous rule (Ps 67)

4. Praise for God’s saving acts (Ps 68)

F. Three Laments and a Royal Psalm (Ps 69–72 [see the parallel section Ps 42–45])

III. Book III (Ps 73–89)

A. Laments Informed by Wisdom and Safeguarded by Praise (Ps 73–78)

1. Wisdom based on individual experience (Ps 73)

2. Lament over God’s apparent rejection (Ps 74)

3. Praise to God, the righteous Judge (Ps 75–76)

4. Lament over God’s apparent rejection (Ps 77)

5. Wisdom based on communal experience (Ps 78)

B. The God Who Saves From Enemies (Ps 79–83)

1. Lament over enemy invasion (Ps 79–80)

2. God will deliver when his people are faithful (Ps 81)

3. Lament over enemy invasion (Ps 82–83)

C. God’s Love for Zion as a Basis for Hope (Ps 84–89)

1. Yearning for restored fellowship with God (Ps 84–86)

2. Celebration of God’s special love for Zion and its citizens (Ps 87)

3. Yearning for restored fellowship with God (Ps 88–89)

IV. Book IV (Ps 90–106)

A. God as a Faithful Dwelling Place Throughout All Generations (Ps 90–100)

B. God’s Love and Justice in Israel’s Past and in Present Need (Ps 101–106)

V. Book V (Ps 107–150)

A. God’s Redemption, Culminating in Prophecies Concerning the Messiah (Ps 107–110)

B. The “Egyptian Hallel” (Ps 111–119)

C. Songs of Ascent With Two Appendices (Ps 120–137)

1. Songs of ascent (Ps 120–134)

2. Appendix One: hymns associated by the Jews with the songs of ascent (Ps 135–136)

3. Appendix Two: A lament for Zion from exile (Ps 137)

D. Davidic Psalms Framed by Thanksgiving and Praise (Ps 138–145)

1. Thanksgiving to the Lord for deliverance (Ps 138)

2. An acknowledgment of no escape from the Lord (Ps 139)

3. Laments for deliverance (Ps 140–144)

4. Hymn of praise to the Lord (Ps 145)

E. Five Hymns Serving as the Doxology for the Entire Psalter (Ps 146–150)