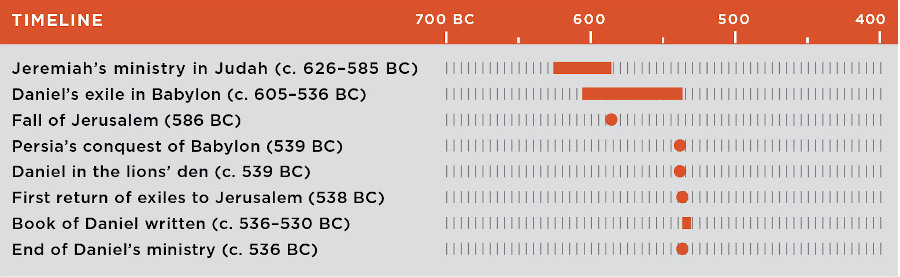

Author: Daniel

Audience: The Jewish exiles in Babylonia

Date: About 530 bc

Theme: The Most High God is sovereign over all human kingdoms.

Introduction

Author, Date and Authenticity

The book implies in several passages, such as 9:2; 10:2, that Daniel was its author. That Jesus believed that the words were at least first spoken by Daniel is clear from his reference to “ ‘the abomination that causes desolation,’ spoken of through the prophet Daniel” (Mt 24:15; see note there), quoting 9:27 (see note there); 11:31 (see note there); 12:11. The book was probably completed c. 530 bc, shortly after Cyrus the Great, king of Persia (who reigned 559–530), captured the city of Babylon in 539 (see 10:1 and note).

Because of the highly specific prophecies related to the Maccabean period (second century bc), some hold that the book was written in the mid-second century, during the period of the oppression of the Jews by Antiochus IV. Therefore all fulfilled predictions in Daniel, it is claimed, had to have been composed no earlier than the Maccabean period, after the fulfillments had taken place. But unless one rejects all long-range predictive prophecy, this conclusion is unnecessary for the following reasons:

(1) The adherents of the late-date view usually maintain that the four empires of chs. 2 and 7 are Babylonia, Media, Persia and Greece. But in the mind of the author, “the Medes and Persians” (5:28; see note there) together constituted the second in the series of four kingdoms (2:32–43; see note there). Thus it becomes clear that the four empires are the Babylonian, Medo-Persian, Greek and Roman. See chart.

![]() (2) The language itself argues for a date earlier than the second century. Linguistic evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls (which furnish authentic samples of Hebrew and Aramaic writing from the third and second centuries bc; see article) demonstrates that the Hebrew and Aramaic chapters of Daniel must have been composed centuries earlier. Furthermore, as recently demonstrated, the Persian and Greek words in Daniel do not require a late date. Some of the technical terms appearing in ch. 3 were already so obsolete by the second century bc that translators of the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) translated them incorrectly.

(2) The language itself argues for a date earlier than the second century. Linguistic evidence from the Dead Sea Scrolls (which furnish authentic samples of Hebrew and Aramaic writing from the third and second centuries bc; see article) demonstrates that the Hebrew and Aramaic chapters of Daniel must have been composed centuries earlier. Furthermore, as recently demonstrated, the Persian and Greek words in Daniel do not require a late date. Some of the technical terms appearing in ch. 3 were already so obsolete by the second century bc that translators of the Septuagint (the pre-Christian Greek translation of the OT) translated them incorrectly.

(3) Several of the fulfillments of prophecies in Daniel could not have taken place by the second century anyway, so the prophetic element cannot be dismissed. The symbolism connected with the fourth kingdom makes it unmistakably predictive of the Roman Empire (2:33; 7:7,19), which did not take control of Syro-Palestine until 63 bc. Also, a plausible interpretation of the prophecy concerning the coming of “the Anointed One, the ruler,” approximately 483 years after the word went out “to restore and rebuild Jerusalem” (9:25; see note on 9:25–27), works out to the time of Jesus’ ministry.

A reasonable case, therefore, can still be made for Daniel’s authorship and an early date for the book.

Theological Theme

The theological theme of the book is summarized in 4:17; 5:21: “The Most High (God) is sovereign over all kingdoms on earth.” Daniel’s visions always show God as triumphant (7:11,26–27; 8:25; 9:27). The climax of his sovereign rule is described in Revelation: “The kingdom of the world has become the kingdom of our Lord and of his Messiah [‘Anointed One’], and he will reign for ever and ever” (Rev 11:15; see Da 2:44; 7:27; 9:25–27 and notes).

Literary Features

The book is made up primarily of historical narrative (found mainly in chs. 1–6) and apocalyptic (“revelatory”) material (found mainly in chs. 7–12). The latter may be defined as symbolic, visionary, prophetic literature, usually composed during oppressive conditions and being chiefly eschatological in theological content. Apocalyptic literature is primarily a literature of encouragement to the people of God (see Introduction to Zechariah: Literary Forms and Themes; see also Introduction to Revelation: Literary Form). For the symbolic use of numbers in apocalyptic literature, see Introduction to Revelation: Distinctive Feature. If Daniel was written in the Maccabean period as a recognized form of apocalyptic literature, then the book’s purpose would not be to predict history, but to interpret it.

The change in language from Aramaic (2:4b—ch. 7) to Hebrew (chs. 8–12) is remarkable. This may be a literary device to reflect the content of these chapters. Chs. 2–7 concern the destinies of the nations of the world, and are therefore written in the international language of the day—Aramaic (beginning in 2:4b). Chs. 8–12 concern the destiny of the nation of Israel, and are therefore written in the language of Israel—Hebrew. See note on 2:4.

Position in the Canon

In the Christian Bible, the book of Daniel is part of the Major Prophets. In the Hebrew canon, however, it is part of the Writings, the third and final section of the Hebrew Bible after the Law and the Prophets. The reason is likely that Daniel was a court official by vocation rather than a prophet in the classical sense. See article.

The theological theme of the book is summarized in this way: “The Most High (God) is sovereign over all kingdoms on earth.” Daniel’s visions always show God as triumphant.

Outline

The outline below agrees with those who perceive two main types of literature in the book (see Literary Features above): (1) court stories about Daniel in historical narrative form (chs 1–6) and (2) visions of Daniel in apocalyptic literary form (chs. 7–12).

I. Stories About Daniel (chs. 1–6)

A. The Setting (ch. 1)

1. Historical Introduction (1:1–2)

2. Daniel and his friends are taken captive (1:3–7)

3. The young men are faithful (1:8–16)

4. The young men are elevated to high positions (1:17–21)

B. Daniel Interprets Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of a Large Statue (ch. 2)

C. Daniel’s Friends Refuse to Worship Nebuchadnezzar’s Gold Image (ch. 3)

D. Daniel Interprets Nebuchadnezzar’s Dream of an Enormous Tree (ch. 4)

E. Daniel Interprets the Handwriting on the Wall: Belshazzar’s and Babylon’s Downfall (ch. 5)

F. Daniel’s Deliverance From the Lions’ Den (ch. 6)

II. Daniel’s Visions (chs. 7–12)

A. The Four Beasts (ch. 7)

B. Daniel’s Vision of A Ram and a Goat (ch. 8)

C. Daniel’s Prayer and the 70 “Sevens” (ch. 9)

D. Israel’s Future (chs. 10–12)

1. Revelation of things to come (10:1–3)

2. Revelation from the angelic messenger (10:4—11:1)

3. Prophecies concerning Persia and Greece (11:2–4)

4. Prophecies concerning Egypt and Syria (11:5–35)

5. Prophecies concerning the antichrist (11:36–45)

6. Distress and deliverance (12:1)

7. Two resurrections (12:2–3)

8. Instruction to Daniel (12:4)

9. Conclusion (12:5–13)