Flavian Scotland. Frontiers of the Roman Empire project/David John Breeze/RGZM

With the end of the Annals and the beginning of the Flavian dynasty the military history of Roman Britain reaches a significant milestone. Up to this point the accounts of military events have been based for the most part on Roman histories and biographies or autobiographies. The evidence may not always have offered the detail wished for by an archaeologist or military historian, but the sources encountered use familiar genres, despite the different stylistic requirements of Roman and modern historical writing; not least of which, is a claim to the veracity of the facts described, to which most students of ancient historiography would subscribe. We have seen that this can be problematic, when truth becomes subjective, even if Tacitus claimed that he wrote his history sine ira et studio (frequently translated as without anger or bias). As with many modern historical accounts, truth is a matter of standpoint and given everybody’s subjective views on the world, staying aloof of personal opinions is more difficult the closer to the events the author feels.

Beyond 70 the only major history that remains with us is Cassius Dio. Unfortunately, between the events of 46 to the death of Caracalla, the history of Cassius Dio actually only survives in the versions abridged by the monk Johannes Xiphilinus, of the Byzantine period, who seems to excerpt the original text, but omits passages which he deems of no interest. The result can be very detailed, as in the account of Boudicca, who appears to have grabbed his attention, or deeply frustrating, when stories are abbreviated and sometimes garbled into a very short precis.

An even more abbreviated version is found in the twelfth century historian Zonaras, who used Cassius Dio as one of several sources, but whose abbreviated sections are more likely to make sense (Millar 2.1999, 2–3). As a result there are problems with the text, but before Dio/Xiphilinus are completely vilified, it should be remembered that even in the small section of Tacitus relevant to Roman Britain there are textual problems, and as far as we are aware, these are not due to abbreviation, but stem from Tacitus’ own stylus.

Dio preferred his history in large brushstrokes: he does not seem to have an agenda or subplot like Tacitus’ in his Annals with his description of Imperial rule as anathema to freedom. Millar also characterizes Dio as likely to omit any detail that is not relevant to the story in hand (Millar 2.1999, 43–45). The overall result is that Dio’s history is not as good a read as Tacitus, a fact which shows in the esteem he is held in comparison with other Roman historians. Most importantly, however, Dio’s history was written in the first half of the third century, over 200 years after the establishment of the Principate. His views are very much influenced by his experience of an Empire that has settled down to Imperial rule, in which the military was accepted as a major source of power. Dio’s recurring topic, if one can be easily identified, appears to have been the abuse of power by those unable to wield it (not a lot of change there from Tacitus) and the way that this could lead to the weakening of internal and external security. Restoring the Republic was, however, no longer an option for Dio; maintaining a strong Principate to ensure a safe Empire was.

Away from Cassius Dio, the majority of evidence for the Flavian period comes from a very different set of sources: in addition to a number of short lines in Pliny the Elder’s ‘Natural History’ and Plutarch’s ‘Discourses’, there are a series of poems (Valerius Flaccus and Silius Italicus), who mention the Flavian achievements in Caledonia and occasionally Thule, written for approval by the ruling family, the Flavians. Another poem praises the achievements of Vettius Bolanus to his son (Statius, Silvae). Finally there is Tacitus’ ‘Agricola’, which is purportedly a belated eulogy by a son-in-law in praise of his deceased father-in-law. The latter has in the last century increasingly been treated as an historical account, bound by the same claims to veracity of Roman historiography, but this is far from the case: Syme described it as a laudatio developed into a biography (Syme 1963, 125). Others have detected within the text the elements of parables on the nature of the good ruler (Braund 1996, 158), as well as elements of other genres. What everybody appears to be happy to agree on is that it is NOT a history.

Laudationes or eulogies, and panegyrics, laudatory speeches praising Emperors and deceased fathers have one thing in common: Romans did not expect them to be utterly truthful; plausibility is more desirable. This is in many ways derived from Roman political culture. Unlike nowadays it was deemed acceptable, at least since the late Republic, to accuse a political opponent in a very direct and scurrilous form, including suggestions of sexual deviancy. At the same time it was understood that a client looking for support by his patron (such as a poet writing a poem) or a relative praising a deceased man (‘de mortuis nihil nisi bene’ – nothing but good things about the dead), was expected to exaggerate his positive achievements.

In such a world of mutual praise and belittlement of each other’s achievements, distortions of the truth were acceptable, the extent of which appeared to have depended on context and person addressed. We have already seen that the accounts of the early governors of Britain given in the Agricola can be a lot more dismissive than their description in other sources, including Tacitus’ other works. The problem of the modern historian writing about the Roman period is often having to guess his way through the conflicting claims and counterclaims. If only one side of the exchange exists, the problem becomes even harder to solve.

Several scholars have in the past suggested that when Dio and Tacitus cover the same material, Tacitus should always be treated as the superior source. This statement is deemed so universally true that it is frequently reproduced without references and is applied as justification to resolve a difference in date between Tacitus’ ‘Agricola’ (83) and Cassius Dio (79) on the circumnavigation of Britain in favour of Tacitus. This assessment is, as far as the author could ascertain, ultimately based on Ronald Syme, who was however, a lot less absolute in his dismissal of Cassius Dio’s writings and restricted his examples to comparisons between the Annals and Histories on the one hand, and Dio on the other (Syme 1963, 388–389). Research has since moved on, and many historians would today argue that differences in portrayal by the two more often reflect a difference in world view and cultural background, rather than a right and wrong portrayal of the same fact (e.g. Woodman, Mellor). A good example of this contrast is the marked difference between the two in the portrayal of Boudicca that we discussed earlier. Much more importantly in this case is, however, the fact that when comparing Tacitus’ ‘Agricola’ with Dio, we are not comparing two historical writings, but a laudatory speech with clear political overtones (Braund, 1996; Woolliscroft & Hoffmann, 2006) with a history written decades later in a much more detached manner.

If Britannia as a remote island had been a recurring theme for the Julio-Claudians, the accession of the Flavians saw the emergence of a new ‘buzzword’: Caledonia. As Flaccus and Silius Italicus stress, the conquest of Caledonia was to be the lasting achievement of the early Flavian dynasty (Vespasian and Titus), only to be trumped by the even more dramatic achievements of Domitian in Germany (the official line taken by the palace, whatever the truth). Braund and others have pointed out that as with many good slogans, the truth was probably more complex (including the fact that according to Tacitus the final conquest of Caledonia came under Domitian with Agricola, and that Wales still needed more campaigning). However, each Emperor needed to stress his military success and being able to point to the extension of the edges of the known world by claiming the conquest of the north of Britain and even Thule, was a feat worth shouting or more literally writing about. The imagery established of these areas being the edge of the world became so powerful that Thule, and to a lesser extent Caledonia, continued for generations in the Roman imagination as the furthest you could go, holding apparently a similar emotional value to the way we might talk about the North Pole or the Moon.

The problems begin when a geographical definition is attempted. Stan Wolfson (2008) has recently published a thorough philological study of the surviving evidence in support of identifying Thule with the Shetland Islands and the suggestion that Agricola’s conquest of the whole of Caledonia was exactly that, the whole of the island; suggesting that the final season and the battle of Mons Graupius must have happened somewhere in Caithness. While his philological studies appear to be hard to fault, it has to be stressed that once again, as in nearly all cases so far studied, neither Agricola’s army nor navy of the final year of campaigning, nor the battlefield, can be identified in the archaeological record. But this does not distract from the fact that the Flavian poets were celebrating the generals as the achievers of complete conquest. Caledonia is not a clearly defined term: it lay to the north of Brigantia, but to judge from how it is used by the poets, it must have meant something equivalent to ‘up north somewhere’, and that was probably as close or as detailed as they wanted to be, especially when writing from the comfortable distance of Rome or the Bay of Naples.

We have, however, two writers that differ in this respect and qualify their description of Caledonia further. One is Statius (a poet of Domitian’s reign (81–96)), who apart from celebrating the opening of the Colosseum wrote a wide ranging series of poems to friends and fellow members of Domitian’s court. In one of these poems he celebrated Crispinus’ incipient career by comparing him to his deceased father Vettius Bolanus. In the middle of celebrating Bolanus’ British achievements, Statius mentions the Caledonian plains. This cannot be brushed aside as a stereotype, quite the opposite: nobody else appears to use the term in this way – and it thus probably conveys some genuine geographical information – and given the general topography of Scotland, limits the area it could have covered to some of the Lowlands, especially the central belt, the Straths on the east coast or the coastal area of Moray and Aberdeenshire. There is, however, not enough data to be more specific.

The other reference comes from Pliny the Elder, who died in 79 in the Plinian eruption of Vesuvius. Pliny was a prolific writer, although only his ‘Naturalis Historia’ has survived. As the preface states, it was finished before the death of Vespasian (70/79), as it is dedicated to Titus Caesar (Emperor 79/81). The text is a kind of encyclopedia of the then known world and while Pliny includes some fantastic stories, most of these are qualified by ‘I have heard’, to express doubts as to their reliability. He mentions not as a rumour, but as a fact, that thirty years since the Roman conquest the knowledge of the island had not progressed beyond the fringes of the Caledonia Silva.

Silva’s first meaning, most commonly used in translations is ‘forest’, but it can also mean ‘mountain range’, as in Hercynia Silva, the Black Forest. Either term suggests that Pliny may have been referring to the Highland fringe. But it would also allude to the fact that despite everything, within ten years of the Flavians coming to power, campaigning at least was progressing well into the Scottish central belt.

Three governors are known from this period: Vettius Bolanus, Petillius Cerialis and Julius Frontinus. The first, Vettius Bolanus has already been discussed in the context of the Civil Wars and Cartimandua. Statius (Silvae V, 2, 142–149) mentions in a poem for his son that he campaigned in Caledonia and that he built watchtowers and forts and captured the breastplate of a king. There is no doubt exaggeration in this poem, and the reference to the breastplate, which is an allusion to the old republican practice of spolia opima, the practice of a general dedicating the breastplate of an enemy leader who had been slain in single combat, is probably one of them.

There are substantial differences as to how to interpret this activity. Most scholars are now agreed that Vettius Bolanus campaigned against the Brigantes and possibly beyond. Identifying the watchtowers is a more problematic issue, as so far we know of two areas where timber watchtowers have been assigned first century dates (despite the notorious absence of any dateable finds within them) in Britain: in the Stainmore Pass (hardly in an area that can be described as a plain, with site elevations above 1,100 feet), and on the Gask Ridge (where at least the southern and northernmost towers can be described as being in a plain, although admittedly the central sector is on higher ground, overlooking Strathearn at about 300 feet above sea level). It is of course possible that we are missing other watchtowers.

A further, more striking problem is the marked difference in the assessment of Vettius Bolanus’ activity between Statius and Tacitus in the Agricola. One claims great military successes, the other credits him patronizingly with having been popular, but not very active. This is a typical case of the exaggeration and denigration discussed above in action, especially as Tacitus (writing in 98) quotes other lines from the same Statius poem (written in c. 95) nearly word for word. He describes the general’s activities on campaign, including exploring the area, selecting sites for camps etc. Statius uses the phrases as descriptions of Bolanus’ campaign experience in Armenia; Tacitus applies the same wording to Agricola (chapter 20). It is hard to avoid the conclusion that this either was a sophisticated literary joke (the kind that most people fail to see the funny side of) or there may have been scores to settle, either of a literary or personal nature.

The importance of this passage has to be stressed, in view of the fact that for the next two governors Petillius Cerialis and Julius Frontinus, we only have Tacitus’ account in the Agricola.

But when, together with the rest of the world, Vespasian recovered Britain as well, there came great generals and outstanding armies, and the enemies’ hope dwindled. Petillius Cerialis at once struck them with terror by attacking the state of the Brigantes, which is said to be the most populous in the whole province. There were many battles, some not without bloodshed; and he embraced a great part of the Brigantes within the range of victory or of war. Cerialis, indeed would have eclipsed the efforts of any other successor. Julius Frontinus, a great man, in so far as it was then possible to be great, took up and sustained the burden; and he subjugated the strong and warlike people of the Silures, overcoming not merely the courage of the enemy but the difficulty of the terrain (Agricola 17 transl. A.R. Birley).

Compared to Vettius Bolanus, both are being clearly complimented on their achievements in Britain, and it is worthwhile to look into the different backgrounds of these two governors. It is noteworthy, that unlike Bolanus, who was Vitellius’ candidate in origin, the latter two were closely linked to the Flavian dynasty. Petillius Cerialis appears to have been married at one point to Vespasian’s only daughter Flavia Domitilla, although she appears to have died before her father became Emperor. If Birley’s reconstruction is correct, he would have also been the father of Vespasian’s only granddaughter: in short, he was very much a member of the new Imperial dynasty (Birley 2005, 65f.).

Cerialis was already mentioned as the legate of the legio IX Hispana, who tried in vain to stop Boudicca’s advance. During the Civil War he raised a cavalry force against the Vitellians to rescue Vespasian’s brother, but failed again. In both cases Tacitus blames his rashness for the defeats. Nevertheless, Cerialis was given by Vespasian the role of pacifying the Batavians after their uprising during the Civil War. Tacitus’ descriptions in the Histories suggest that he was an inspired and very lucky general, although at times his own worst enemy, especially if women were involved. Nevertheless, despite the lack of final detail, as Tacitus’ account stops in mid-sentence, we know that he managed to resolve the situation in Lower Germany and was then sent to Britain, possibly to resolve the Brigantian situation. He arrived, bringing the legio II Adiutrix, which had been under his command in Germany, to replace the legio XIV Gemina. He is credited by Tacitus with the largest military success in Britain, but then protocol demanded as much from a prince of the Imperial house.

Archaeologically, we know a number of forts that are built all over the Brigantian territory during his governorship: the most closely dateable one is Carlisle with its dendro-date of 72; other sites that are traditionally associated with him include the legionary fortress of York (home to the legio II Adiutrix), but as we have seen in the last chapter there is some debate over its date. In addition, it is usually assumed that the legionary base at Caerleon was occupied during his governorship. The move might have been in preparation for further campaigning in Wales, although this is not mentioned in any of the surviving records. Further forts in the north of England almost definitely belong with these key sites: Hodgson (2009, 8–10) has recently suggested a list, but further research is likely to add to them.

Cerialis appears to have been not just consolidating the situation, but campaigning as well. If Tacitus’ Agricola is to be believed, his achievements, as we have seen, are mentioned in the summary of governors, as well as probably obliquely in the description of Agricola’s second and third season (Agr. 20, 3 and 22, 3), where tribes that had previously been involved in warfare are described as surrendering and giving hostages or being faced with continuous warfare summer and winter alike.

Cerialis left most likely late in 73, in time to return to Rome for his second consulship in 74. We do not know what happened to him later, but it is generally assumed that he was dead by the time Tacitus wrote the Agricola in 98.

His successor Sex Julius Frontinus clearly was still alive in 98 and as we understand it, was one of the most powerful men in Rome, an Emperor-maker and the power behind the throne of the Emperor Nerva (96/98). We know little of his early career, but he was praetor urbanus in 70, and thus on 1 Jan 70 the highest ranking official in town, able to call together the Senate and co-ordinate the handover of power to Domitian, Vespasian’s son and representative in the city in the aftermath of the execution of Vitellius a week earlier. Later in the same year, he was also, as one of the generals of Cerialis, involved in the pacification of Gaul and Germany, and apparently received the surrender of the Lingones.

He succeeded Cerialis in 73 as governor of Britain and remained there until summer 77, when he returned to Rome. We know from his later career that he accompanied Domitian on his German campaigns, and c. 84/85 he was proconsul of Asia. Afterwards he turned to writing, with interests ranging from surveying to two titles on military matters, of which the stratagemata, a handbook on military tactics, survives.

During the events of 96/97 Frontinus appears to have been one of the leading statesmen behind the coup that deposed Domitian (Grainger 2003) and thus possibly one of the people who encouraged Tacitus to write the Agricola. Frontinus afterwards became curator aquarum (the man in charge of the water supply in Rome, a job that resulted in another book) as well as being involved in other roles in the governments of Nerva and Trajan.

He has been singled out by Tacitus as the person who finally defeated the Silures, which as Davies and Jones (2006, 53) have argued may be shorthand for the whole of the south of Wales. In addition the two passages in the Agricola (20, 3 and 22, 3), cited in connection to Petillius Cerialis, may apply just as much to him as to his predecessor. Similarly the fort building in northern England discussed above, apart from Carlisle, cannot be separated between these two governors on the basis of archaeological finds. Nor is it currently possible to date the early Flavian network of over forty forts in Wales to the individual governorships. The largest of these new sites is the legionary fortress in Chester (which replaced Wroxeter), which must have been started either by Frontinus or very early in his governorship by Agricola.

Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the next governor had a very different background. He shares with his two immediate predecessors a close connection to the Flavian cause: while mourning his mother, who had been killed by Otho’s soldiers in northern Italy in 69, he became one of the earliest supporters of Vespasian in the area. Up to this point his mainly civilian career had been somewhat lacklustre, but did involve a military tribuneship during the Boudiccan uprising. Having levied troops during the Civil War for the Flavians in Italy, his career took a turn for the better he became legate of legio XX Valeria Victrix, the legion that had been the leaders in the mutiny against Trebellius. It is possible that he saw action as legate under Petillius Cerialis, but the references are rather vague. After his legateship he was made governor of Aquitania, a peaceful province, and after his consulate was given the governorship of Britain by Vespasian.

In the summer of 77 Agricola arrived in Britain. The description of his activities in his son-in-law’s account takes up twenty-one chapters, thus instead of offering a retelling, the following summary of his activities needs to suffice:

77: Agricola arrives late in the season and immediately starts campaigning against the Ordovices in north Wales, followed by an attack on Anglesey.

78: Consolidation of earlier achievements, Romanization policy discussed by Tacitus.

79: Agricola’s army advances ‘usque ad Taum’, possibly the Tay in Scotland; fort building.

80: Consolidation of what is won so far. Tacitus states that a frontier could have been found between Forth and Clyde, if the honour of the Roman people had permitted it.

81: Crossing in the leading ship to discover people hitherto unknown. Agricola considers conquering Ireland.

82: War on people beyond Bodotria (Forth estuary) by land and sea. Night attack on the legio IX Hispana. Revolt of the Usipi and their accidental circumnavigation of Britain.

83: Final advance, Battle of Mons Graupius. Official circumnavigation of Britain.

In addition to the campaigning activities the archaeological record shows that Agricola was involved in the construction of forts and fortresses. The best evidence comes from Chester, where the construction of the fortress probably started just before his arrival. However, the find of inscribed water pipes naming the governor, which is in itself an unusual feature seen otherwise mainly in the city of Rome, suggests that he took a very strong interest in the construction of the fortress, and especially in the unusual features such as the Elliptical Building, which remains unparalleled (Mason 2000, 66–95; Mason 2000, 110–119).

There have been over the years substantial arguments on how reliable this account is and views range from utterly reliable (Ogilvie and Richmond 1967) to problematic (Hanson 1978; Woolliscroft & Hoffmann 2006) and many shades in between. At the heart of it is once again the question of genre. If we are to accept that the Agricola is a laudatory speech as well as a biography and a parable, then its level of reliability is no higher than celebratory poems like the Statius discussed earlier. The level of geographical detail presented is certainly no higher than the information we have discussed in Tacitus’ or Cassius Dio’s historical works, and thus reconstructing detailed routes of advance is problematic, to say the least. This is, however, not the place to review the entire argument, which has been discussed several times elsewhere; except to correct a misunderstanding that appears to have crept into some of the literature: neither Woolliscroft (2002) nor Woolliscroft & Hoffmann (2006) have stated that all of Scotland was conquered by Petillius Cerialis instead of by Agricola (contra Hodgson 2009, 13), but they have always suggested that all four Flavian governors are equally likely to have participated in the conquest of the north and that not enough evidence exists to date to offer a more detailed scenario.

The account of the governorship of Agricola culminated in a now famous set-piece battle: Mons Graupius. The battlefield is (once again) presented in the Agricola in the most cursory terms: the site lies on a slope, the Britons occupied the high ground, the Romans approached from lower ground, with a river dividing them from their enemies. A description that differs mainly from the battlefield of Caratacus in the provision of the two ridges that were used by Caratacus as elevated fighting platforms; while Paullinus’ battlefield is equally on the high ground, this time with no river, but sufficient obstacles that he could not be surrounded. One has to ask: does Roman Britain in the first century only offer one type of battlefield, or is what Tacitus describes as ‘the perfect battleground’ in Roman (or at least Tacitus’) eyes, chosen by every general worth his salt?

Due to the vague description there are numerous slopes that have been put forward as Mons Graupius, covering most of Scotland north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus, but concentrating on the east coast. Wolfson (2008) has recently proposed Caithness as another possible site of the battle (although the current author has so far failed to identify a battlefield site in the area that would fit even Tacitus’ limited description, given Caithness’ propensity for comparatively flat, but very waterlogged countryside). Many of these make tactical sense and can be fitted with the Tacitean account – in some cases they have also been associated with the evidence from marching camps – but none has so far produced the sort of evidence that we now associate with Roman battle sites: scatters of broken military equipment, not least hobnailed boots or possible graves, such as those found in Kalkriese and Harzhorn in Germany; and as we have seen in the case of Boudicca, the fact that the description could fit so many possible sites may suggest that we do not have sufficient information to locate the site from the historical account alone.

Ardoch fort and camps. David John Woolliscroft

Thus so far we are still no closer to understanding the strategic function of the battle, while its literary function within the Agricola is clear enough – it is the final victory, the crowning glory to a seven year governorship, nicely topped off by naval achievements by the fleet. The perfect culmination to a long career, worthy of a noble governor, even if the bad Emperor Domitian did not appear willing to agree with Tacitus once Agricola returned to Rome. There is a substantial difference between the literary function and a strategic reason for the battle. Ending a war with a decisive event makes good narrative sense; but as we have seen in the Caesar, Caratacus and Boudicca chapters, the Iron Age peoples in the south of Britain may have defined their objectives differently. Their defeat in a large battle appears not to have been a reason to offer universal surrender, but seems to have been a moment of reconsidering tactics. Neither Caratacus nor Boudicca appear to have considered surrendering after their lost battles (at least if you follow Dio’s account, rather than Tacitus as we have seen). Interestingly, a look at the history of Republican Rome shows that the Romans took a very similar view of their wars. The historical accounts of the third and second century BC are full of instances where even after a crushing defeat like Cannae, the Romans just ‘dug their heels in’ and raised another army to continue the fight.

After a hundred years of experience of fighting in Britain, it is interesting to note that Roman historians (and possibly generals) appear to have been unwilling or unable to recognize the same determination in other Iron Age societies. Did Agricola really believe that the Battle of Mons Graupius was the final step towards the conquest of Scotland, as well as the last battle during the governorship, or are we just led to believe this to be so, as it suited the narrative of Tacitus at this point?

One further major problem persists: according to Tacitus the circumnavigation of Britain, a feat ranked as being as important as the military success of Agricola, happened at the same time as the final battle at Mons Graupius, making Agricola’s final year in Britain a double success. This may be surprising, but proving beyond doubt that Britain was an island and thus not linked to the Continent also meant establishing the size of the island, and as such added substantially to Rome’s knowledge and ability in a military sphere to predict future threats and upcoming military commitments. Islands, because of the problems of landing more armies from outside, intrinsically lend themselves to total conquest and the development of a comprehensive defence in a way rarely offered by areas on larger landmasses. In addition, it should also be remembered that until recently, the discovery of major new territories was considered an important achievement in most European nations. Agricola’s circumnavigation is also mentioned in other sources: a minor essay by Plutarch (De defectu oraculorum) and in Cassius Dio. In Plutarch the reference is oblique; Agricola is never mentioned: but one of the participants of the discussion, the Grammatikos Demetrius, has just returned from an expedition to Britain. The date of this probably fictitious dialogue is given in Olympiads, a Greek form of time keeping that counts the Olympic games since their inception. When resolved into modern dates it translates most likely into 82, which would mean Demetrius would have to have returned from the voyage before it actually took place according to Tacitus. It could be argued that as this is a fictitious dialogue, the dates are irrelevant, but the conventions of this genre suggest that use of historical characters and dates was supposed to give the piece credibility, inferring that it was advisable for the authors to get the dates right. The second source, Cassius Dio mentions the circumnavigation outright; in fact he links the award of the triumphal ornaments with the circumnavigation rather than any military success. In Dio’s account, however, the circumnavigation is dated to the reign of Titus. It has been argued that this just means that Dio is wrong, because Tacitus is the better historian. But as we have seen, the Agricola is not a historical work, and thus Dio’s claim should be looked at on its own merit. The date of the circumnavigation in Tacitus is designed to create a point of resolution in a carefully constructed narrative; that would not have been achieved if the triumphal ornaments had already been awarded three years earlier (compare the feeling of deflation in the Annals, between the early years of Ostorius Scapula, which culminates in the capture of Caratacus and the later years, where he is bogged down in unrewarding fighting in Wales). For Cassius Dio or rather Xiphilinus the award of the circumnavigation was one of the lesser pieces of news in the context of the major crisis of Titus’ reign, worth mentioning in passing, but little more. On the whole, events in this category are rarely distorted: why bother, if they are just ‘background noise’? It would thus seem that Cassius Dio, unlike Tacitus, had little reason to change the date of the circumnavigation.

With the return of Agricola to Rome, the literary sources for Roman Britain become scarcer; instead inscriptions from Britain and elsewhere replace historical accounts. A brief reference in Suetonius’ Life of Domitian says that Domitian killed a governor of Britain called Lucullus for naming a new design of lance after himself (Suet. Domitian 10, 2–3); this is symptomatic of the new style of evidence. But in the absence of any other records of further conquests or discoveries, it is probably correct to assume that with Agricola the conquest of Britain achieved its maximum extent. The remainder of the story, which is one first of consolidation and then increasingly of defence of the status quo, has a very different character.

The archaeological evidence for the conquest and occupation of Scotland is substantial. As well as a large series of marching camps there are numerous forts in Flavian Scotland, in addition to those which were rapidly developing all over northern England. Given the substantial number of forts (they were often larger than normal), it has been convincingly argued that it is unlikely that these forts all existed at the same time, as the garrison of Roman Britain is unlikely to have been large enough. It is thus more likely that the Flavian period saw rapidly changing garrisoning patterns, with forts established and then quickly moved when the situation changed. Disentangling this history on a fort by fort level is likely to take decades and is very much dependent on large scale excavations to separate individual phases and establish their full extent. At the moment there are forts, such as Cargill, Cardean and Strageath (Woolliscroft & Hoffmann 2006 with further literature), where areas within the fort see rebuilding, while at others (e.g. Fendoch and Elginhaugh), no major repairs were postulated by the excavators (Richmond and MacIntyre 1939; Hanson 2007).

There are also substantial differences of opinion as to the earliest dates of these forts, and as a result, differences of opinion exist between scholars as to how the conquest and occupation of Scotland is viewed. The two supposed fixed points for this debate are Carlisle, with its dendro-dates of 72 on the western side, and Elginhaugh on the outskirts of Edinburgh, for which the excavator proposes a date of construction on the basis of a dispersed coin hoard to 79 (Hanson 2007).

Hanson’s assumption is that the Roman advance progressed on both sides of the island at the same speed and thus that no fort further north could be earlier than Elginhaugh, for which he postulates an important strategic position along Dere Street. This view, however, is not as uncontroversial as Hanson and others (Hodgson 2009) make it out to be. The crucial coin hoard of 79 was ‘dispersed’: some of the coins were found together, other coins including the one that has been claimed to date the hoard to 79, were found spread on the Roman surface, thus raising doubts about its original context. Also as presented in the final report, there is little information on the crucial way in which the hoard relates to the different layers of construction, repair and demolition within the principia where it was found. No sections or detailed plans were published which would establish beyond doubt these important relationships. In addition, recent rescue excavations in the fort’s annex produced a coin of the Emperor Trajan (97/117) (DES 2009, 120) in the backfill of an enclosure ditch. This particular find, which is most likely to have been lost during the second century, possibly the Antonine period, suggests that in addition to the Flavian period, later activity took place in the fort, thus querying its status as a single period site abandoned for good in 86/87.

Flavian sites north of the Forth Clyde. David John Woolliscroft

A much wider problem is, however, the question of how far dates from Elginhaugh can be transferred to other forts and how deeply connected it is with the role of Carlisle, built in 72. This early date for the latter fort was first proposed nearly a hundred years ago by Bushe-Fox (1913) on the basis of early Samian found at the site, and while it did not find acceptance then, the point was taken up again by E. Birley (1951), who saw in Carlisle a fort that separated the Brigantes in the South from their Scottish supporters in the North. He proposed at the time a very different scenario for the Roman invasion of Scotland, which is worth quoting in full:

It seems a reasonable inference, that before Dere Street was built, to carry the main Roman trunk line from York into Scotland, the principal northwards road followed by early man was over Stainmore, across the Cumberland plain and so into Dumfriesshire; and that is the line of the Roman road from York to Carlisle, Birrens and beyond. We may be justified, I suspect, in supposing that the Votadini of Northumberland and the eastern Lowlands were either pro-Roman or neutral, and that the main force of Venutius’s supporters was found among the Selgovae and Novantae in the centre and west; and it would be logical, in that case, for Cerialis to aim first at securing Carlisle, and then perhaps to mop up all the centres of Venutian resistance to the South of it. But we can hardly exclude the possibility that his campaigns continued northwards into Scotland; for when we turn to examine what Tacitus has to say about the governorship of Agricola, it is most remarkable, that for all the superficial impression of active operations in his narrative, it is not until the fifth season of his governorship that Tacitus is able to credit Agricola with meeting tribes previously unknown. (E. Birley 1951, 57)

This passage would suggest a very different scenario from Hanson, with the Roman advance mainly progressing on the western side of the Cheviots and bypassing the Votadinian territory (on the East coast of Scotland, Southeast of Edinburgh) for the most part by following roughly the course of the modern M6/74 and A74. This scenario has again recently been proposed by Jones (2009). If this were the case, then Elginhaugh’s position would not be looking North, but South, guarding an exit from Votadinian territory in a similar fashion to the Nottinghamshire and Lincolnshire forts and camps in the 50s and 60s.

Wolfson (2008) suggests that the conquest of Scotland probably saw ebbs and flows, with advances and regroupments, but also with conquest in different parts of Scotland progressing at different speeds and by different methods, resulting in similar scenarios to those we have seen in the South, with parts of the province apparently free of military occupation, while neighbouring districts may show substantial evidence for intervention.

As we have seen the literary sources are once again unable to lend support to any of the theories on the Roman advance into Scotland for lack of detail. In this particular case and as we will see for most of the remainder of Romano-British history the evidence is mainly to be found in the archaeological record, in the form of inscriptions or structures. These, as we have seen, usually document the consolidation phases of any military action, while the conquest phase again remains invisible.

For Scotland this conquest phase has, however, left further evidence in the form of frequently large marching camps, a substantial number of which form series, and in addition often cluster at specific sites, leading to ‘clusters’ of intersecting marching camps which thus provide a chronological sequence between camps of different design (see plan of Ardoch page 127).

Marching camps in Scotland. Frontiers of the Roman Empire/RGZM/David J. Breeze

Following the long standing research of Prof. J.K. St. Joseph from 1951 onwards (inter alia 1951), many of the 220 camps known from Scotland have traditionally been grouped into series on the basis of the available historical evidence associated with campaigning in Scotland. In the case of the camps north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus these were usually associated with either the campaigns of Agricola or the campaigns of Septimius Severus (see below).

In addition to these there are a number of camps in the Scottish Lowlands, which currently form independent series, which cannot be ascribed to any campaign known from the historical accounts.

The most common way of cataloguing these camps is by size, but further features are the gate types: particularly the so called ‘Stracathro’ gate type, a very characteristic form of gate construction, where one side curves outwards, while the other approaches at an oblique angle. It has been identified so far at sixteen sites. However, although these camps are traditionally associated with the Flavian period; they appear to be no longer common in the mid second century and are frequently found close to (later?) Flavian forts, their sizes vary from 1.5 to 24.5 ha. They thus do not represent a series of campaign camps (Jones 2009, 75–6). In addition the high level of occupation in the Scottish Central belt makes it much harder to link the patterns observed in the Scottish Lowlands with the camps north of the Forth Clyde isthmus.

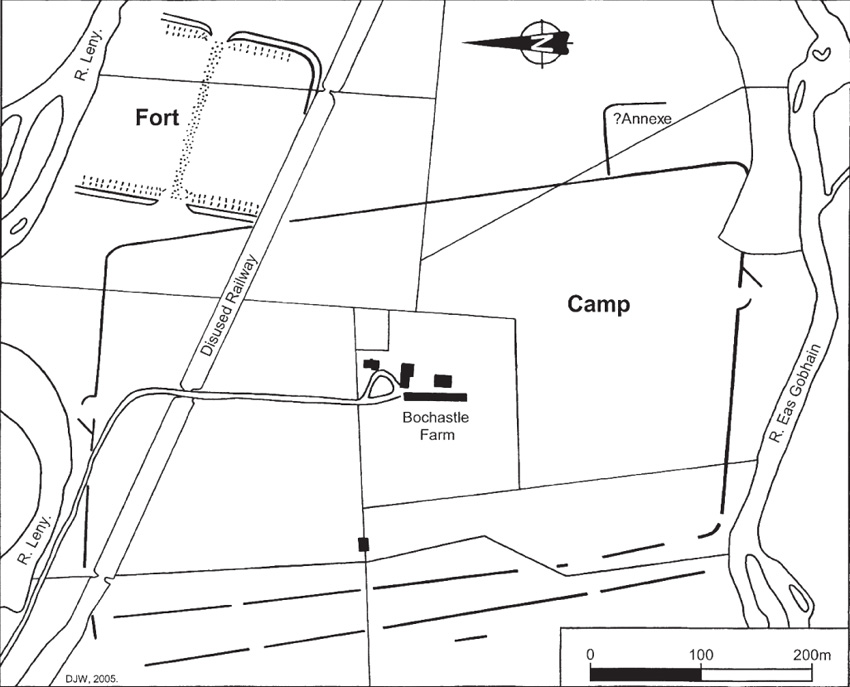

Bochastle camp and fort, note the Stracathro gates in the camp. David John Woolliscroft

Most camps have seen only small scale excavations over their ditches to confirm their existence; large scale excavations in the interior are rare, with Kintore being the most extensive. The large scale excavations of this 110 acre camp in Moray produced substantial evidence for internal structures, especially in the form of ovens. The radiocarbon dating of these ovens suggests that the main phase of occupation dates to the late first century, thus probably coinciding with the period of Flavian campaigning.

However, the excavations also underlined that this camp was not just used for one night, but that some of the ovens were repaired, suggesting re-use of the camp at a later point. The evidence for re-use has now been recognized at other sites too, although more commonly this evidence is in the form of ditches that have been allowed to silt up (as at Bochastle), before being recut, or a camp being re-used by inserting a smaller installation inside the earlier ditches (as in Dunning) (Jones 2009b, 23). All this is likely to complicate the building history of the camps as well as our understanding of their use.

Rock-cut marching camp ditch at Raedykes. David John Woolliscroft

At the moment we are reasonably confident that the 110 acre camps belong to the Flavian period, while the 63 acre and 130 acre series might belong to the second or third century (see the chapter on Severus for a discussion of these). The general distribution of the camps of Roman Scotland suggests that on the whole they tended to follow the later Roman roads: a line of camps follows Dere Street in the East, while another series follows several Roman roads out of Carlisle heading North or into Dumfries.

The extent of Roman control in Scotland is also still a matter for debate. The 110 acre series which reaches furthest north, starts at Normandykes to the south of Aberdeen, and continues via Kintore to Ythan Wells I/Glenmailen and Muiryfold into Moray. There are so far no camps detected further north, despite extensive flying programmes in the Highland area. As there are also so far no 110 acre camps south of this area, these four are unlikely to represent a full campaign. In addition, in the middle of these camps lies the 144 acre camp (58 ha) of Durno. Although the latter is frequently associated with the Flavian campaigns and has sometimes been associated with the final battle of Mons Graupius, it needs to be stressed that it is unique in its size, but only 9 ha smaller than a series of 165 acre (c. 67 ha) camps in the Scottish Lowlands north of the Newstead that are more commonly associated with the Severan campaigns.

It is thus apparent that currently despite significant research time being invested over the last 100 years and more, our understanding of the conquest of Flavian Scotland is far from complete. It is clear, however, that the Flavian Emperors were initially willing to invest substantial amounts of men and material in the conquest and retention of Northern Britain, especially of Caledonia. The return, in addition to the taxable agricultural produce and population, consisted of the discovery and exploitation of substantial mineral deposits, many of which appear to have been (at least initially) capitalized by an army. The conquest of Wales brought, in addition to copper and iron, which for the most part remained in private hands (or so the archaeological records appear to suggest), silver and lead (galena) (e.g. in Flintshire) and in Southwest Wales small amounts of gold at Dolaucothi near Pumpsaint fort.

In the North of England and Scotland, galena deposits included those in Derbyshire and in the Northern Pennines near Whitley Castle, possible deposits in the Lake District as well as the silver mines in the Scottish Lowlands in Drumlanrig, all of which can now be shown to have been exploited by the Romans within a short time of their arrival in the area.

In addition to the large number of auxiliary forts built, the Flavians eventually even moved one of the legions north to a new base at the foot of the Highlands at Inchtuthil near Dunkeld. This suggested that the occupation was considered permanent. Unfortunately, both for the Roman Empire and the Roman legions involved, the early eighties saw the middle Danube erupt into full scale warfare with the Dacians attacking across the river. A series of commanders were sent to stabilize the situation, usually with little success and sometimes with catastrophic losses, which may have included some of the legions. As the Danube frontier was essential for the security of Italy and thus Rome, Domitian was forced to redeploy troops from other provinces to stabilize the situation. This included the removal of one of the British legions and probably its associated auxiliaries. The result was an extended province that now had to be held with a reduced level of manpower; an amount that had proved barely adequate in a smaller province in the late 60s the last time a legion had been withdrawn. As a consequence, we see throughout the North of Britain and Wales a re-organization of the army. This redeployment is particularly striking in Scotland, where all of the forts north of the Forth-Clyde isthmus, including the legionary fortress, were abandoned early in 87. There appear to have been some attempts to forestall the withdrawal south of the Forth-Clyde line, but over the next decade more and more forts were abandoned and eventually the Roman military occupation withdrew to a line between Carlisle and Newcastle. Britannia omnia capta, statim missa – Britannia was completely conquered and immediately let go, as Tacitus (Hist. I.2) summarized the Flavian involvement.