It was fossils like the ones Mary discovered that scientists relied on the most in helping them to decipher the global geologic record.

—SHELLEY EMLING, BIOGRAPHER

Eleven-year-old Mary gathered her hammer and chisel and set out for the high cliffs along the coast. The night before, there had been a violent storm with strong winds and droves of rain. She knew the water had washed away layers of dirt, uncovering shells and fossils. With any luck, she’d be able to find a few unique specimens to sell to tourists as curiosities.

As Mary walked along the beach, she noticed something strange. Lying near one of the cliffs were some objects that appeared to be large bones. Intrigued, she immediately went to get a closer look. Mary began chiseling away the rock near the bones, and the more she uncovered, the more excited she became. In front of her was a huge skeleton, unlike anything she’d ever seen. With its long tail, short flippers, and sharp teeth, it looked like a sea dragon!

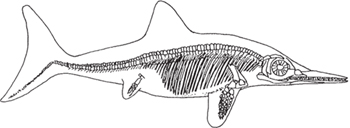

What Mary hadreally found was one of the first and most complete skeletons of an Ichthyosaurus, or “fish lizard,” a dinosaur that lived about two hundred million years ago. This thrilling childhood discovery inspired her to spend the rest of her life hunting for fossil remains, an occupation that would bring her fame and respect in the world of science.

Ichthyosaurus

Mary Ann Anning was born in 1799 in Lyme Regis, a town on the southern coast of England. Her father was a carpenter who collected and sold fossils as a hobby. He often took Mary and her brother to search the coast for shells, sea dollars, and other interesting items. Tourists loved the coiled fossil shells that the Annings sold. At the time no one knew exactly what these were, but it would later be discovered that they were the fossil remains of ammonites, prehistoric mollusks that lived during the time of the dinosaurs.

When her father died in 1810, eleven-year-old Mary and her family decided to continue selling fossils. She found her first dinosaur skeleton just a few months later. She hired some quarrymen to extract it from the rock and then sold the skeleton to a man who bought things for museums. Mary’s creature was later named Ichthyosaurus.

After this first discovery, Mary continued with her business, always searching for new fossils. When she was in her early twenties, she discovered a second dinosaur skeleton. This one was called a Plesiosaurus, or “near lizard,” because of its long, thin body and its four elongated flippers that looked almost like legs. A few years later, Mary found the skeleton of a birdlike dinosaur, the first ever to be found in England, which was later named Pterodactyl, or “wing finger.”

For the remainder of her life, Mary continued hunting and selling fossils. Mostly, she sold the small fossilized shells to tourists, but her dinosaur skeletons attracted the attention of wealthier and more scholarly customers as well. Over the course of her career, she found other ichthyosaurs and plesiosaurs, which brought high prices from scientists and collectors and increased the world’s knowledge about these ancient creatures.

Pterodactyl

By the time she died in 1847, Mary had become well-known for her discoveries. As a prehistoric-fossil hunter, she helped found a new area of study. And as one of the earliest professional female scientists, she opened new doors for women.