PALACES OF ENTERTAINMENT

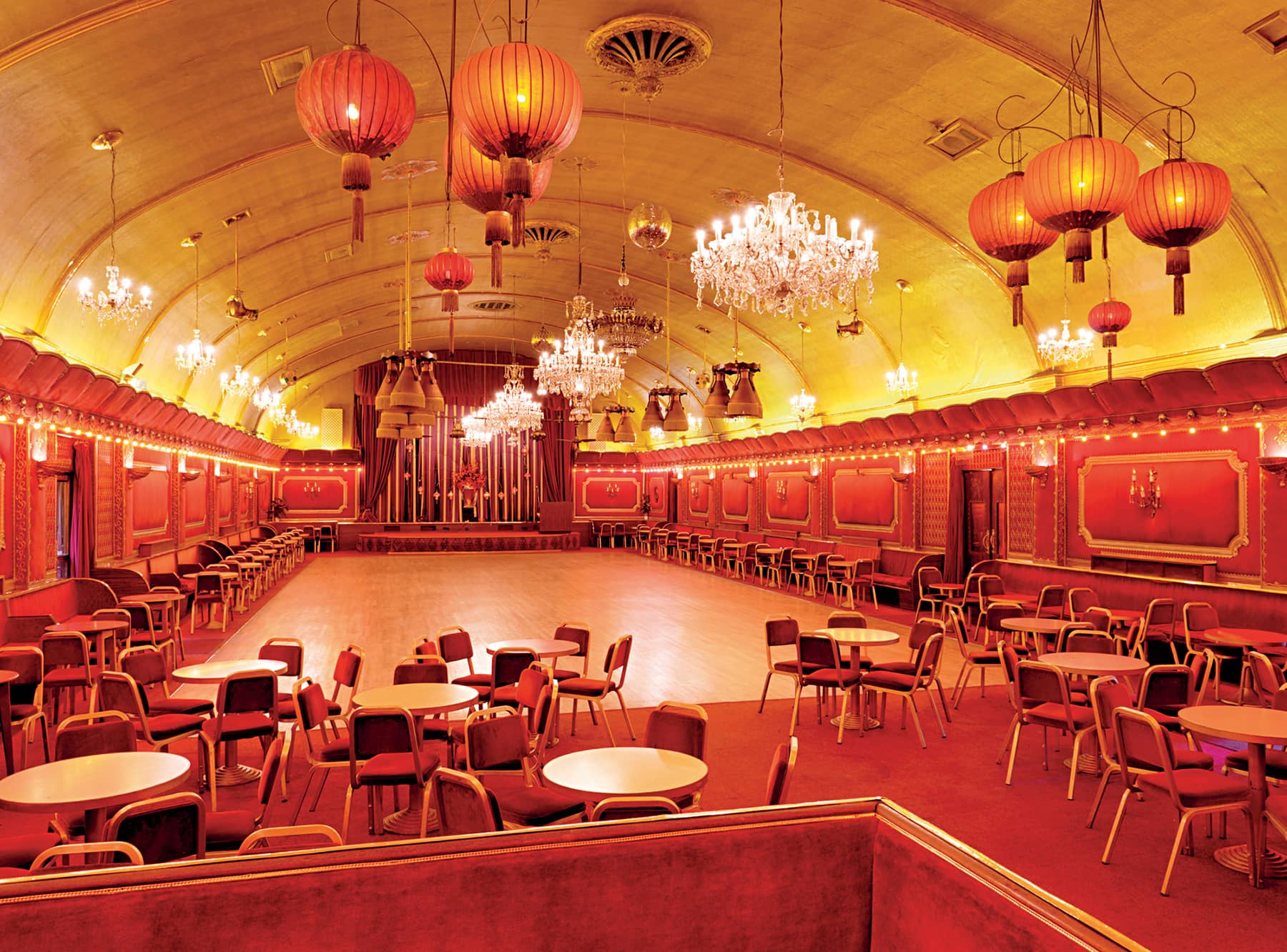

Chandeliers, disco balls and reproduction oil paintings on the ceiling of the Gold Ballroom.

The Rivoli Ballroom

The vaulted ceiling in the ballroom is the only visible legacy of Rivoli’s cinema ancestry.

The Rivoli Ballroom is a wonderful anachronism, unveiled at the dawn of the 1960s to evoke the style of an age just passed, and as years have passed its charm has increased.

In the scarlet-and-gilt ballroom there is a riot of influences at work. Illumination is by Chinese lanterns, French chandeliers, glitterballs, candelabra and scallop sconce uplighters. Wall decorations consist of padded red velour panels with pelmets and gilt framing. At the end is a proscenium with a red plush curtain and raised stage for the band; at the opposite side, a raised viewing dais. Banquettes, fixed tables and paired chairs run along each side for couples. The most important feature is the sprung Canadian maple dance floor. Only the barrel-vaulted ceiling was left unchanged from the ballroom’s former life as a cinema.

The building started out as the Crofton Park Picture Palace in 1913, a modest cinema typical of its time, built without a balcony and seating 525. In 1931, it was re-named the Rivoli Cinema, a café was installed, and outside a façade was added in Art Deco style, including pilasters topped with plasterwork urns and a raised parapet. The seating capacity was increased to 700 in an extended auditorium.

It remained an independently operated cinema into the 1950s, squeezed by the growth of television and the grip on film distribution held by the ABC and Rank chains, which controlled the latest Hollywood releases. The last picture show for the Rivoli Cinema was an incongruous double bill of Reach for the Sky and The Nat ‘King’ Cole Musical Story, shown on 2 March 1957, after which the building was closed for more than two and half years. A local businessman and dance enthusiast named Leonard Tomlin applied to have the cinema converted into a dance hall, and plans were approved by the local authority in September 1958. It opened on Boxing Day 1959.

Red plush continues in the Ladies’ Powder Room. The design of intersecting curves seen in the marquetry on the door is continued from the foyer.

As revealed then, the Rivoli Ballroom did not conform to one particular style or period, although it certainly harked back to before the Second World War, possibly aiming for the 1920s. It is self-consciously retrospective, and there is signage for facilities described as the ‘Ladies’ Powder Room’ and the ‘Gentlemen’s Cloakroom’. The foyer has marquetry panelling with decorated doors. Bars were added on each side of the dance floor, and a second function room seems to date from this time: a neoclassical gold-walled room in Adam style. The ceiling is covered with reproductions of old romantic rococo-style oil paintings.

Producers of music videos have discovered the Rivoli as an atmospheric location. Elton John’s ‘I Guess That’s Why They Call It The Blues’ was filmed there in 1983, and the following year part of Tina Turner’s Private Dancer, setting a trend for more to follow, and also for television commercials and trailers. Scenes for at least six feature films have been shot here, including Spy Game, where its bar masquerades as an East Berlin location for Brad Pitt and Robert Redford. It has also been a nightclub for crime film Legend, a restaurant in Muppets Most Wanted and in Avengers: Age of Ultron it appears in a flashback sequence where dancers perform the lindy hop.

The side bar buffet with booths was added during the Rivoli’s conversion to a ballroom.

In January 2008, the building was Grade II listed by English Heritage, which cited its ‘highly unusual interior’, the total effect of which is ‘luxuriant, exotic and deeply theatrical’.

It served a live music venue for smaller bands through the 1960s and, more recently, for numerous fashion shoots. Ballroom, Latin, salsa and jive dancing continue at the Rivoli. It is tempting to see it as a romantic survivor sustained over time by the elegant art of ballroom. The sign outside the Rivoli still declares ‘Dancing Tonight’.

VISITING INFORMATION

Rivoli Ballroom, 350 Brockley Road, SE4 2BY

Open for events year round.

Wilton’s Music Hall

The view from the stage. The auditorium is in muted colours now. The gallery was once gilded and the alcoves filled with mirrors.

The survival and conservation of Wilton’s Music Hall, the oldest remaining musical hall anywhere, was a struggle that lasted fifty years and the scars can be clearly seen. That was the aim of the restorers, who in 2015 completed what has been described as ‘a kind of invisible mending’, which gave a sound structure and preserved an astonishing patina.

In the early 1850s, John Wilton built an entertainment hall behind three Georgian houses in Graces Alley, in the area between Whitechapel and Wapping. One of these properties was a pub known as The Mahogany Bar, which already had a concert room behind. Wilton soon acquired the lease on an adjoining house, and built a second, bigger auditorium in 1859, one of the first built specifically for emerging style of music hall entertainment. It suffered a fire in 1877 and was rebuilt, but operated as a theatre for only four more years. One of the last turns was the legendary George Leybourne, performing in the character of the singing and dancing dandy ‘Champagne Charlie’.

The hall was taken over by the Wesleyan Methodists, who reopened it as The Mahogany Bar Mission, after dispensing with the namesake wooden counter and bar where alcohol had been sold. Services were held in the theatre, and the building played a community role in chapters of East End history, including serving as a soup kitchen during the dockers’ strike of 1889, and delivering relief to shelterers during the Blitz of 1940–1. The Methodists ran the mission until 1956, and afterwards the building operated as the Coppermill Rag-Sorting depot. Wilton’s Music Hall should then have been swept away as part of a widespread slum clearance programme by London County Council in 1964, and demolition plans were drawn up. But at a public meeting for the closure, John Betjeman, poet laureate and pioneering conservationist, and theatre historian John Earle, spoke in support of keeping it. The building gained listed status in 1971, but the structure was semi-derelict. Fundraising efforts and restoration started and stalled. A trickle of piecemeal building work kept Wilton’s standing, aided by a diet of film location and music video work.

The helical-twist barley-sugar columns supporting the gallery date from 1859.

Firstly, the London Music Hall Trust funded some work in in the 1980s and the building became a little more secure. A significant milestone was the first live act before an audience since 1881, a performance recitation of T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland in 1997 by Fiona Shaw, a staging that was praised for perfectly harnessing verse to Wilton’s own poetic melancholy. The Wilton Music Hall Trust, formed in 2004, financed the restoration of the music hall itself in the ‘conservative repair’ style and the houses at the front were rebuilt. Nearly all the original features were retained, while introducing modern heating, electrical and lighting systems.

Wilton’s Music Hall hosts opera, puppetry, classical music, cabaret, dance and magic shows, and also offers tours. These take place on some Mondays.

The gas-lit entrance was originally the door to a pub; Wilton’s Music Hall is landlocked by surrounding buildings.

All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club

Preparing the grass at Centre Court, rain protected since 2009.

Few walks in London can rival the sheer air of excitement generated on a mid-summer’s day when striding from Wimbledon rail station, situated on the flat, up over the hill, through Wimbledon village, to the long expanse of Church Road, the home of Wimbledon Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club. Between late June and early July, what would otherwise be a leafy suburb, just another one of the city’s villages, is abuzz with the energy and passion of world-class sport. Suburban calm is replaced by the circus of the international tennis circuit.

The Wimbledon Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club was founded in 1869 as a croquet club, with tennis being incorporated into its title in 1877. Initially, its home was located at nearby Worple Road, only moving to the current Church Road site in 1922. Today, the venue comprises two major show courts, seventeen ‘outside’ courts, impressive media and practice facilities (a further twenty-two courts) as well as eateries, tourist shops and a permanent archive and museum. In addition to the Championships proper, the Club has also hosted Olympic tennis, occasional Davis Cup ties, and an important annual international junior tournament (Girls and Boys, since 1947). The Championship tournament is one of the four grand slams shared out between Melbourne, Paris and New York. It is the only remaining grass tournament at its level.

There are Wimbledon rules. These range from the 8mm height of the grass on the lawns to the detailed requirements for the players’ clothes (whites are still imposed, despite corporate sponsors’ designs). Perhaps the real magic of the place has been its ability to adapt and change, keeping up with trends in the modern game while also seamlessly maintaining a strong sense of tradition. Certainly the Club and the Championship have moved with the times. For example, rain delays are now a thing of the past, a covered Centre Court being opened in 2009. Similarly, the old Number One court, which backed directly on to its more prestigious neighbour, was completely rebuilt, and is today a more comfortable, if less evocative, arena than in the past. The critical Hawk-Eye electronic line rule system was introduced in 2006, and has become as much of the show as the strawberries and cream. For Wimbledon fans, the essential thing is that all these substantial changes have been successfully incorporated into the traditions of the past. This process of silent modernisation has been relatively smooth because the existing order is so well-established, and that is assisted by the great sense of intimacy of the place. Show court sight-lines remain excellent, enabling the spectator to become engrossed in every point. So-called outside courts constantly host exciting contests, especially in the first week of the Championships when many of the top-ranked players find themselves located just a few feet from the fans. Courts nestle close beside each other and the action is never far from view. The speed of play is therefore tangible, the balls ripping backwards and forwards at speeds that often defy the human eye.

The inscription on the Gentlemen’s singles trophy is: ‘The All England Lawn Tennis Club Single Handed Championship of the World’. In 2009, with no space left to engrave names, a plinth with an ornamented silver band was designed to accompany the Cup. The Ladies’ singles trophy is a silver salver, sometimes called the Rosewater Dish. Winners receive a three-quarter size replicas of the trophies.

Wimbledon has witnessed some of the most entertaining tennis matches of all time, and personalities have also often shone through the score-lines. Few can forget the rise of the junior Boris Becker (first victorious in 1985), the cool elegance of Björn Borg, and the will to win of a generation of American greats (McEnroe, Connors, Agassi). In 1987, it was the Australian Pat Cash who added to the rituals of the tournament when he invented the tradition of the final-day victor clambering to their family and trainers in the crowd, now almost obligatory. The Ladies’ competition has generally witnessed more skill than individual flamboyance. In recent times the victories of outside bets (Jana Novotná, Marion Bartoli, Petra Kvitová) have nevertheless made that part of the competition more exciting than the serve and double-fault routine that sometimes dogs the men’s draw.

It is important to recall that for years the special atmosphere for British fans was precisely not to have a home favourite who could win. The rise of first Tim Henman and then Andy Murray changed that, and for at least the last fifteen years there are far more partisan crowds than ever.

The record books tell us that the first male victor was Spencer Gore (1877) and the triumphant equivalent female contestant was Maud Watson (1884). Three men share the record for most championships won: William Renshaw (1880s), Pete Sampras (1990s) and Roger Federer (2000s). In the Ladies’ singles, the pre-eminent figure, with nine championship victories, is Martina Navratilova.

The three latest English Ladies’ champions. A successor is awaited.

VISITING INFORMATION

All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club, Church Road, SW19 5AE

Wimbledon Lawn Tennis Museum open daily 10am–5.30pm; last entry 5pm.

Tours may be booked online.

Regent Street Cinema

The George and Dragon plaque above the auditorium is an emblem of the old polytechnic.

When architect Tim Ronalds came to design the rebuild of the Regent Street Cinema in 2010, he described it as like discovering a burial chamber in a pyramid, finding what was then a lecture theatre inside an Art Deco cinema, which had been built inside a Victorian galleried theatre. In its latest restored form, Regent Street Cinema seats 187 in an auditorium decorated with neoclassical plasterwork, all in the style of 1927. Hidden above the barrel-vaulted ceiling is the original 1848 cast-iron roof structure. A Compton organ installed in 1936 has been retained.

Across its history the cinema has projected early scientific demonstrations, Victorian novelty illusions, newsreels, and mainstream and art-house films. A type of cinema pre-history was the lantern slides projected with live-actions shows, and a popular illusion known as ‘Mr Pepper’s Ghost’, based on Charles Dickens’ The Haunted Man, first performed in 1862. The Lumière projections launched its role as a picture house, and the cinema was leased out by the nearby Polytechnic of Central London and operated under the names Cameo-News, Cameo-Poly and Cameo-Classic. In recent memory, it was one of central London’s major art-house cinemas, specialising in foreign films during the golden age of classic European cinema. Its fortunes declined afterwards and, after a short period as a live theatre, it briefly went back to cinema use, before closing in 1980 and reverting to the polytechnic, now the University of Westminster.

The restoration was to the latest acoustic and visual standards with 4K digital projection equipment, while maintaining 8mm, 16mm and 35mm optical projection. Regent Street Cinema maintains diverse programming with double bills, world cinema, modern independent and classic films.

VISITING INFORMATION

Regent Street Cinema, 309 Regent Street, W1B 2UW

The Gate Cinema

While the seating in the Gate is modern, its decoration is true to 1911.

Notting Hill is home to a good selection of cinemas, the most intimate of which is The Gate. The unremarkable façade on Notting Hill Gate gives no clue to what lies within: 180 comfortable red plush seats on a single floor, in a perfectly preserved baroque Edwardian room. The auditorium dates from 1911, when the Golden Bells Restaurant was converted into a picture house named the Electric Palace by architect William Hancock, one of at least five conversions he designed during the first London cinema boom before the First World War.

By 1934, it was the Embassy, and then renamed the Classic Cinema in 1957. Much of the magic of any cinema lies in its programming, and the Classic Cinema made its mark by becoming a popular revival house, screening many classic Hollywood films. A speciality was the screening of late shows every night of the week, and it was routine to see long queues outside at 11pm. In 1974, it became the Gate Cinema, operated by independent distributor Cinegate. In the art house tradition, it successfully programmed Fassbinder’s early films, Jarman’s Sebastiane and La Cage aux Folles.

In 1994, the Gate Cinema was designated a Grade II listed building by English Heritage, which found a little-altered early cinema auditorium with exceptionally lavish decoration. There is ‘abundant plaster fruit’ on the ceilings, walls divided into bays by pilasters, mouldings, foliage scrolls and roundels. The dominant colours remain red and gold. It was restored in 2004 with the addition of air conditioning. The Gate Cinema continues as a popular cinema with varied art house programming, and is now operated by the Picturehouse Cinemas chain.

The National Theatre

The Lyttleton Theatre with its adjustable proscenium, and a mostly bare-stage adaption of Turgenev’s Three Days in the Country, designed by Mark Thomson.

With three auditoriums staging more than a thousand performances of twenty-five or more different plays at the South Bank each year, the National Theatre is a massive and powerful machine for drama.

Ambitious in concept and epically protracted in its gestation, the National Theatre experienced 100 years of prehistory, negotiations, ideas and planning before the foundation stone was laid on the South Bank in 1951. Even that provided to be a false start, and the site changed three times before building work properly started in 1969 for completion in 1976. After controversy over its funding, architecture and leadership, the National Theatre has established itself as a serious and eclectic place for all classic drama, distinct from the commercial theatre of the West End, while still building a reputation for staging and launching popular hits. Shakespeare has been the most performed playwright, while War Horse is the most successful play in the NT’s history.

The NT is rare among theatres in handling nearly all parts of production in-house, including set-building, scene-painting, digital design, and costume- and prop-making. More than 700 people work on its 5-acre site. There can be seven productions in the repertoire at any one time, including tours and transfers. The National possesses all the tools to do this job.

Largest of its auditoriums is the Olivier, which can accommodate 1,150 people. When the theatre was planned, openstage arenas were rare. The spirit of its inspiration was the Greek amphitheatre at Epidaurus, and the architect for the National Theatre, Denys Lasdun, developed the idea from a simple sketch showing an open stage placed in the corner of a square room. The Olivier is large for the number of seats it contains, and the NT claims that no place in the Olivier is far from the actors’ point of command, and the span of the seats matches their effective field of vision. It possesses one of the largest pieces of stage machinery in Britain: the drum revolve, a 125-tonne double turntable several decks deep, which incorporates two lifts. As the Olivier itself is three floors above ground level, the revolve operates over five storeys. It was built into the original design, but for more than ten years it was used mainly for shifting scenery from the dock before being properly deployed dramatically. The electrical drive and control systems have been replaced and strengthened. Since then, the drum has been in regular use, serving many shows, allowing a ship to rise and sink, or a castle to appear out of the mist.

The National has one Green Room, which is used by actors from all of the theatres.

When the NT was designed, a proscenium stage was also specified, and this was the Lyttleton, which can house an audience of 890. The proscenium is adjustable and can be open-ended, or made to create an orchestra pit for up to twenty musicians. The third schemed theatre was the Cottesloe – now Dorfman – a smaller rectangular space that can have the stage installed at one end, lengthways or in the round.

The NT’s first artistic director was Sir Laurence Olivier, appointed in 1962, with the company lodging at the Old Vic while the South Bank theatre was built. Peter Hall took the NT into the new building and was director until 1988, and is credited with harnessing the full potential of its three playhouses and setting a wide repertoire.

A props table at the NT; all props can be made in-house, and more than 21,000 pieces are held by the hire department.

When completed, the cast-concrete edifice of the NT, with its terraces and fly towers, was found forbidding by some critics, and has been said to resemble a fortified position on the bank of the river. Prince Charles described it as, ‘a clever way of building a nuclear power station in the middle of London without anyone objecting’, and in 1976 the South Bank area itself was bleak and undeveloped, and remained that way for most of the decade afterwards. As the NT overcame controversy and criticism, and found success on its stages, the South Bank area itself came to be transformed, with the establishment of Tate Modern, the Globe Theatre and London Eye.

In 2015, under the NT Future programme, the theatre unveiled a series of updates to make itself more open and accessible, including the Clore Learning Centre, with its classes and workshops, the Sherling High-Level Walkway, which gives visitors views into the backstage Max Rayne production workshops for set construction and design.

This staging of Timberlake Wertenbaker’s Our Country’s Good, designed by Peter McKintosh, used the drum revolve seen on the right.

VISITING INFORMATION

National Theatre, Upper Ground, SE1 9PX

http://www.nationaltheatre.org.uk/discover/backstage-tours

Building open 9.30am–11pm Monday–Saturday, 12pm–6pm Sunday.

It is possible to explore the unseen areas of the theatre on daily backstage tours.

Normansfield Theatre

Normansfield could originally seat at least 350, and includes a stepped gallery with an ornate iron front.

The marvel of Normansfield is how an 1879 proscenium stage theatre survived unaltered in a time capsule, to be restored and reopened 125 years later. The theatre is a tribute to the medical pioneer Dr John Haydon Langdon Down, who gave his name to the congenital chromosomal imbalance known as Down’s Syndrome. At Teddington in south-west London, he had commissioned a sanatorium called Normansfield, developed from 1868 as a home for the learning-disabled, and licensed as a private asylum with classrooms, workshops and a farm. Dr Langdon Down’s progressive views on treatment valued the role of drama, music and entertainment as a therapeutic tool, and in June 1879 an entertainment hall was opened.

The proscenium is richly coloured and gilded and is surrounded by elaborately decorated panels on all sides. Four doors – two functional and two false – flank the stage. These were expertly painted, as were the panels on the riser at the front of the stage. Some researchers have attributed certain of these pictures to Marianne North, the notable botanical painter whose pictures are displayed at Kew, although that has not been established beyond doubt. Above the doors are four pre-Raphaelite paintings presenting the muses Tragedy, Painting, Music and Comedy; the artist is unknown.

Displayed on the walls are six wooden panels with paintings of figures in period costume. These are characters from Gilbert and Sullivan’s Ruddigore, and came from the original Savoy Theatre production of the operetta, where they functioned in the production as swivelling doors, although no explanation of why they came to Normansfield has been uncovered.

Normansfield’s scene-changing system and its collection of stock scenery are rare surviving examples of the apparatus and illusion of theatre that started to disappear at the end of nineteenth century. In addition, more than eighty painted flats have survived, depicting landscapes, gardens, palaces, baronial halls or splendid rooms, capable of creating a setting for a range of plays from melodrama to pantomime, together with backcloths and borders to frame the scene. Theatrical scenery of the time tended to have a short life, pieces being remodelled or scrapped. New systems of overhead scenery-changing were introduced in the commercial theatre shortly after this, but Normansfield did not update its scenic groove system or scenery. When the most ambitious theatrical productions, staged at Normansfield by an amateur company drawn from staff and friends, came to an end around 1908, a long hibernation began of the stage and scenery.

The woodland scene on this backcloth is framed with profiled wing flats as an avenue to lead the eye; the hinged wing painted with classical column is part of a false proscenium.

For Normansfield as a medical care institution the running costs started to exceed the income from fees after 1945, and the National Health Service took it over in June 1951. It was then known as Normansfield Hospital. At this time the stage was rarely used for any kind of performance, but the hall remained in use for therapeutic group sessions, meetings and as a badminton court. Some damage was inflicted on the wooden panels. The fragile disused scenery was stored unseen, but everything remained intact and not quite forgotten.

Normansfield Hospital continued to develop until the end of the 1960s, but afterwards changes in healthcare policy and programmes such as Care in the Community were to be introduced, and the hospital was steadily run down. Long before the closure, in the early 1980s, a Theatre Project Committee started negotiations about preservation with the health authorities, which continued for more than ten years. The Friends of Normansfield, the Theatres Trust, the Greater London Council, English Heritage and Richmond Council were all eventually engaged. When Normansfield closed as a hospital in 1997, the scenery was removed and stored for conservation, and much of the site used to build new housing. As a part of permission to develop the housing, Laing Homes restored the hall and stage with as few changes as possible. Some of the scenery was replicated and returned. The building, still known as Normansfield Theatre, is now owned and managed by the Down’s Syndrome Association as the Langdon Down Centre, which includes a Museum of Learning Disability and the historical archive material of Dr Langdon Down.

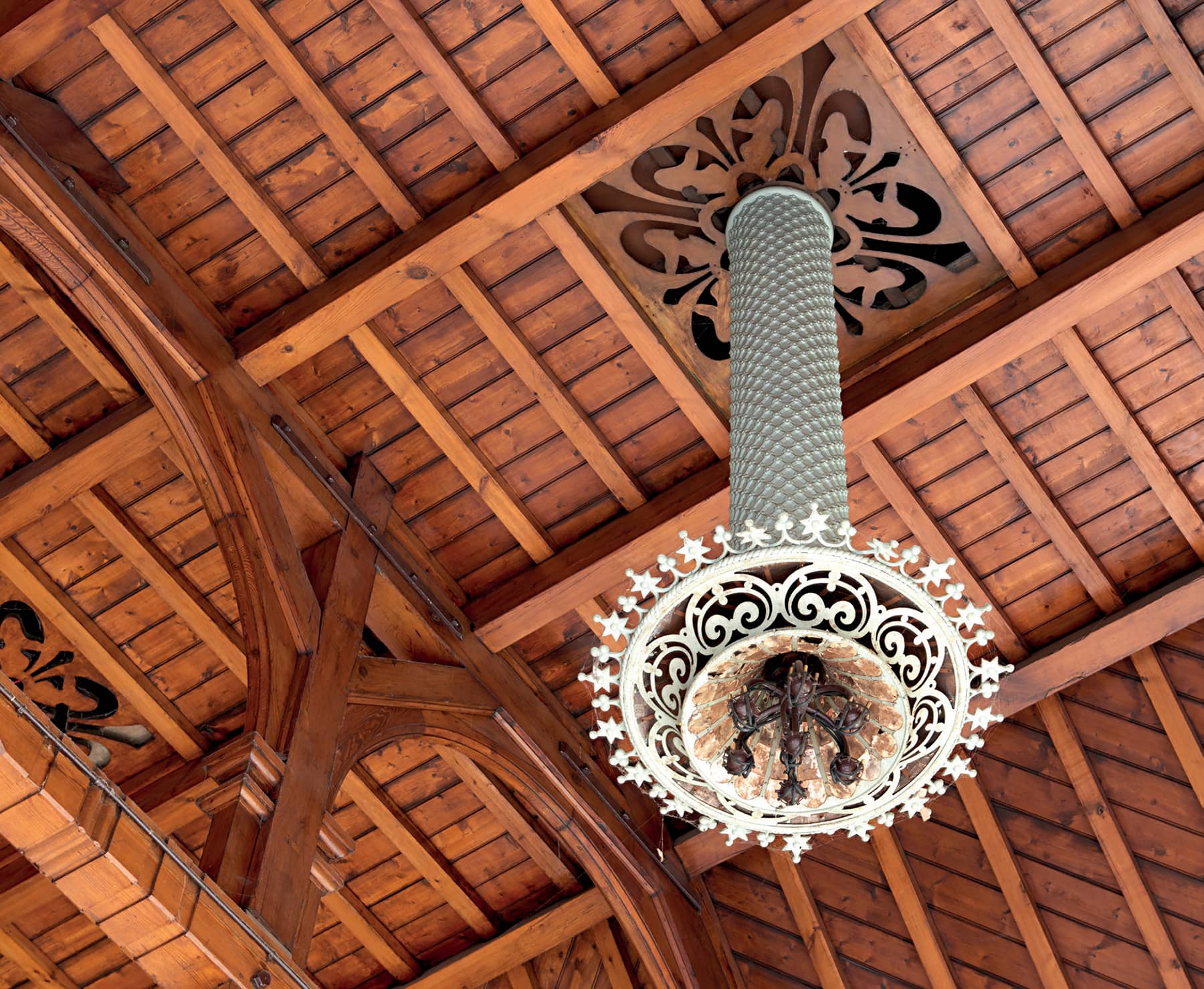

The pendant ‘sun burner’, a combined gas chandelier and ventilator, as installed in 1879.

VISITING INFORMATION

Normansfield Theatre, Langdon Down Centre, 2a Langdon Park, Teddington TW11 9PS

http://www.langdondowncentre.org.uk

Open 10am–1pm on Saturdays, and a number of public performance events

are staged in the theatre each year.

Wigmore Hall

A grand piano is positioned just inside the apse, which contains most of the stage.

Wigmore Hall is one of the most highly rated venues in Europe, with its stage perfectly sized for soloists and chamber musicians. It frequently provides a showcase for young artists making their professional London debuts, and the repertoire extends from the Renaissance to contemporary jazz and new compositions.

The auditorium’s most famed feature is its responsive acoustic quality, widely praised, but hard to explain in terms of modern design science. During the refurbishment of the hall in 2003–4, acoustic engineers were commissioned to investigate this elusive embedded quality and concluded that ‘the geometry would not be favoured by current day designs, yet it is revered by international musicians and audiences alike’. Although the overall rectangular shape is favourable to a good sound, many of the most elegant features – such as the elliptical ceiling, the apse and half cupola – are concave focusing surfaces, which would certainly not be favoured today. The writer Vikram Seth described Wigmore Hall as ‘the sacred shoe-box of chamber music’, referring to both its proportions and its reputation.

In May 1901, German piano manufacturer Bechstein opened a showroom and concert hall in London at 36 Wigmore Street. For the hall, Bechstein commissioned architect Thomas Edward Collcutt, whose portfolio included the Savoy Hotel, the Palace Theatre in Cambridge Circus, Lloyd’s Register Building and interiors for twelve P&O liners. He designed an auditorium in a neo-Renaissance style, panelled in mahogany with a frieze in red Verona marble surmounted by gilt moulding. In the foyer, marble and alabaster decorate the walls and floor. A Sicilian marble stairway with an alabaster handrail climbs to the balcony. Today, Wigmore Hall retains most of its original features, including some gas lights, which are still lit for every concert. During the Edwardian age, it was called Bechstein Hall, and hosted music from artists such as Nellie Melba and Enrico Caruso. Composers Camille Saint-Saëns and Percy Grainger performed here and its reputation as a recital venue grew rapidly.

During the First World War, the British government wound up German-owned companies. Bechstein’s assets were seized as enemy property, and the hall was sold at auction, the buyer being Debenhams. Included in the sale were the showroom and 137 pianos. Rented out under a long lease, the hall re-opened under the name Wigmore Hall and Piano Galleries in 1917. In the 1920s and 1930s Casals and Segovia performed here and the Wigmore Hall flourished. From 1946, the management of the hall was taken over by the Arts Council Music Department. During the 1950s, Elisabeth Schwarzkopf and Joan Sutherland sang, and Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears performed. Westminster City Council took over the lease in 1986. Since 1992 it has been owned by the Wigmore Hall Trust, which in 2005 purchased a long lease of 300 years.

As for the treasured acoustic, special care was taken to preserve this quality during the most recent restoration. There are 552 seats on a flat floor in the stalls and in the balcony. After a series of tests, the temptation to rake the floor for better sightlines was resisted. The carpeting – a feature which is held to go against good acoustic qualities – was retained. Another detail, rarely noticed by visitors, is found on the ceiling, where there are a series of glazed laylights allowing daylight to enter the auditorium. One laylight is incomplete. During restoration in 2004, it was found that the light nearest the stage was missing four panels. The architect proposed reinstatement of the glass for the best visual effect, but before that was done the acoustic specialists investigated the effect of putting the glass panels back. After a series of tests with musicians and skilled listeners, with the openings covered and uncovered, the openings were left as they were.

Marble, mahogany and plaster on walls and ceiling line the perfect auditorium for small chamber ensembles; symbolist painting depicts music as the fruit of divine inspiration.

VISITING INFORMATION

36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP

Open for public concerts all year round.

Gala Bingo Club

From the gallery, the spirit of the Doge’s Palace in Venice is evoked.

The emergence of lavish movie theatres in Britain was spurred by rivalry among cinema chains ABC, Gaumont and Odeon between the coming of the talkies in 1928 and the start of war in 1939. The most spectacular of all the super picture palaces created in that era was the Granada Tooting, which continues today as the Gala Bingo Club, with its extraordinary interior well-preserved.

The up-and-coming Granada cinema circuit was being developed by Sidney Bernstein, owner of Bernstein’s Theatres Ltd, and he hired Theodore Komisarjevsky, a cosmopolitan designer-director, who had created productions on the stage in London, Paris and New York. Komisarjevsky was trained in architecture, and had worked as a theatre producer in his native Russia, also working in ballet and opera. He had come to London in 1919 and his creative reputation grew rapidly beyond that of being simply a set designer. He was first hired by Bernstein to work on the interior of the Phoenix Theatre in Charing Cross Road. His third design commission for Bernstein was the new cinema at Tooting, which became a sensation on its opening in 1931. It was not the Italianate-style façade and entrance designed by architect Cecil Massey that generated the excitement, but Komisarjevsky’s Venetian Gothic interior.

It owed much to a design trend known as the ‘atmospheric theatre’, which started in the United States. This was characterised by putting complex decoration on the cinema’s side walls to create a fantasy world, typically evoking an Italian garden or a Spanish courtyard, a Moorish city or an Asian temple, sometimes with a cleverly lit sky-painted ceiling. The Granada Tooting was in the atmospheric style, but the choice of Venetian Gothic was startlingly original, and came entirely from the imagination of Komisarjevsky. Gothic arches are found all over the auditorium, around the proscenium, on the side walls and over the doors, some with colonnades and gables. Some of the arches are filled with paintings in a medieval style: of musicians, a wimpled maiden and an African drummer. There are false back-lit windows, stained glass, a ceiling over the stalls painted with blue sky and clouds, and a coffered ceiling behind. It was ‘the world of the Palazzo on the Grand Canal, recreated in the midst of south London’, according to architectural historian David Atwell.

The entrance staircase, with every detail, including the bench seat, designed by Theodore Komisarjevsky.

Everywhere there is a rich theatricality of decoration. The grand foyer evokes a gigantic baronial hall from the middle ages, with a beamed ceiling and carved panelling. At the top of the main stairs, the balcony lobby is a cloister, with more than seventy mirrored arches in a hall of mirrors for those going to take their seat in the circle.

The sheer scale and opulence of the Granada is overpowering to modern eyes, and any cinema with a single auditorium capacity of more than 3,000 is hard to understand in the age of the multiplex. Yet cinemas then were offering audiences a rare escape from the humdrum everyday world, based on the fantasy provided by the film on the screen and the fantasy realm of the picture palace environment.

Tooting Granada has a wide, deep stage, designed for live performance, and an orchestra pit. There are two organs, one of which is a Wurlitzer that rises from the stage in classic style, and whose console was once coupled to a white grand piano on stage. In Bernstein Theatres the programming of films and live acts was eclectic. There would sometimes be two feature films, or one film with a variety show. At other times a circus performed, and the pantomime Jack in the Beanstalk with a cast of sixty. After the war came Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lee Lewis, Gene Vincent, The Beatles, Roy Orbison, The Rolling Stones and Jimi Hendrix. The last live act was The Bee Gees in 1968. As cinema audiences diminished to 600 per week by the 1971, closure was inevitable, and the last film was shown November 1973. It re-opened as a Granada Bingo Club and was taken over by Gala Bingo in 1991. It is the only Grade I listed former cinema in England.

The hall of mirrors in the gallery lobby offers a dazzling optical infinity effect.

The gothic arches and gables are original; later came the seating for the café and for bingo, which has saved the old Granada.

VISITING INFORMATION

Gala Bingo Club, 50–60 Mitcham Road, SW17 9NA

www.galabingo.com/clubs/tooting

Open 10.30am–11pm Monday–Saturday; 11.30am–11pm Sundays.