REMARKABLE SHOPS

A typically eclectic display room at LASSCO, including marble columns recovered from an old house in St James’s, a pair of painted wooden columns from a fairground ride, an English Rococo Revival white Carrara marble chimneypiece and glass-and-gilt chandeliers.

LASSCO, Brunswick House

This office does double duty as a showroom at Brunswick House, with everything in the picture for sale: from the steel-and-cast-iron firebasket to the six-branch chandelier dating from around 1800.

Brunswick House is the headquarters and flagship of LASSCO, the London Architectural Salvage and Supply Company. It is a 250-year-old mansion surviving as an island outpost in Vauxhall beside towering apartment blocks, a supermarket and one of the busiest and widest gyratory traffic systems in London. Its rooms contain hundreds of pieces salvaged from old buildings; chimneypieces and firegrates, doors, and street signs and lamp posts. Passengers riding on buses passing LASSCO can glimpse Italian statues in the courtyard and chandeliers in the upper rooms.

LASSCO Brunswick House serves different purposes. Some of its spaces are rooms made up into display areas for antiques, clocks and chandeliers, and furniture. Eclectic, sometimes eccentric and not always antique, there might be found at any one time a life-sized cutout of Tony Curtis from a cinema foyer alongside a delicate wirework birdcage. Ionic columns in imitation of the rarest of marbles stand salvaged from the unfinished conversion of Park Lane Playboy Club to a millionaire’s residence.

Each room is minimally restored. There is a roof terrace and courtyards with statuary, fountains and garden curiosities. Other places – the saloon, smoking room, study parlour, library and cellar – may be hired for receptions and meetings. Throughout, nearly everything on display is for sale. Also in business at Brunswick House is a restaurant and bar.

The saloon was once the drawing room of the Duke of Brunswick, and later the snooker room of the London South Western Railway Scientific & Literary Institute, and it is described as ‘impressively shabby’. Below on the ground floor is the library, with its ceiling braced with what is reputed to be a piece of railway track against the weight of the snooker tables, and refitted with an elegant reclaimed fireplace. There are a series of cellars with ancient flagstones and old brickwork, which are the remains of an earlier building used as further display and entertainment areas.

Brunswick House dates from 1758, standing in what were once acres of parkland close to the river, going down to a mooring stage on the Thames. Part of the house was leased by the exiled aristocrat Freidrich Wilhelm, Duke of Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, this being anglicised to Brunswick. His German home had been overrun by Bonapartists, and his father killed in battle against Napoleon. All his adult life the Duke fought against Napoleon. He lived briefly at Brunswick House, returning to the fray on the continent in 1813 to be killed at the Battle of Quatre Bas just before Waterloo.

This eclectic dining room display spans the styles. Every piece is labelled and for sale, including two sets of Hogarth prints: Marriage à-la-mode and The Four Stages of Cruelty.

Brunswick House’s pleasant location was quickly eroded by encroaching industry. The London South Western Railway built its first London terminus close alongside in 1838. Gasworks, a locomotive building works, Nine Elms engine shed and goods yards grew up around the house and alongside the river. A railway viaduct cut off the view southwards. Brunswick House, damaged and much neglected, was bought first by a gas company and then by the LSWR. The railways used its ground floor as goods yard offices from 1860, with a railwaymen’s club on the upper two levels. A huge cold store was built close behind. In this landscape the survival of Brunswick House was freakish. The rail tracks and sheds surrounding it were built up in the nineteenth century and then run down in the mid-twentieth. When the Victorian gas works and rail yards were demolished, the building remained the British Railways Staff Association Club. The much-run-down area started to undergo regeneration in the 1990s, with the opening nearby of the MI6 headquarters building at Vauxhall Cross in 1994 and the apartment towers of St George Wharf in 2000. Brunswick House remained in the ownership of the railway social club until 2002.

A Late Victorian stained-and-painted trefoil, by Cottier & Co. of London, dated c.1890. It was removed from St George’s Church, Perry Hill, Catford.

It was purchased by in 2002 Adrian Amos, a pioneer of the business of architectural salvage, who had started the LASSCO firm at a redundant church in Shoreditch during the 1970s. LASSCO had owned a salvage yard at Bermondsey since 1999 for reclaimed building materials and Brunswick House was acquired to operate as showrooms and offices. The house was first restored from the ravages of squatters who had stripped much of the interior before LASSCO opened shop in 2005. It is a distinctive landmark where Wandsworth Road meets Nine Elms Lane alongside the bus station and the roaring one-way road system with five lanes of traffic. Brunswick House will continue to stand out in the regeneration of Vauxhall, stamnding close to what is dubbed the Embassy Quarter, where the giant cube of the new US Embassy is developing.

Cast-iron street signs from around London. The stars are decorations from American barns. The giant aluminium E is one of several salvaged from a prominent building along the South Bank, all displayed in the cellar rooms.

VISITING INFORMATION

LASSCO, Brunswick House, 30 Wandsworth Road, London SW8 2LG

Open 9am–5.30pm Monday–Friday, 10am–5pm Saturdays, 11am–5pm Sundays.

L. Cornelissen & Son

Sable, synthetic, signwriting . . . brushes of more than a hundred types are stocked.

L. Cornelissen & Son is a supplier of artists’ materials on Great Russell Street, not far from the British Museum. The charm of the store is in the Victorian shop-fittings, which are exactly those created by the founders, and also in the range of specialist artists materials they contain; drawer after drawer is filled with pigments, brushes, prepared colour, gold leaf and printmaking equipment. It is possible to buy traditional quill pens made from goose and turkey feathers, cut by hand and cured in hot sand.

Cornelissen has been trading since 1855. The sign above the door states ‘Artists’ Colourmen’, a description of those who blended pigments for painters from the eighteenth century onwards. Originally, the ‘colourmen’ bought pigments from an apothecary in order to grind and mix bespoke colours for individual artists. The colourmen developed into suppliers of ready-made colours off-the-shelf, firstly oil paints, then watercolours. By the middle of the eighteenth century many of the larger colourmen’s shops offered a wider range of products, including brushes, paper and canvas.

Louis Cornelissen was a Belgian domiciled in Paris who, after the 1848 Revolution, left for England to set up shop in Covent Garden. His first line of business was supplying lithographic materials to printmakers and artists. Later, Cornelissen offered a full range of materials.

Colourmen marked their canvases and stretchers with individual stamps and labels, and it is possible to trace Cornelissen-supplied canvases used by painters such as Rex Whistler and Walter Sickert. These stencils give the company address as 22 Great Queen Street; this was L. Cornelissen’s home from 1861 to 1987.

It remained a family-owned company until Leonard Cornelissen, grandson of the founder, died in 1977. The business was purchased by Nicholas Walt. It was compelled to move from Great Queen Street after the lease there expired in 1987. The shop in Great Russell Street, Bloomsbury, is a listed late-seventeenth-century building, with a nineteenth-century front that closely resembled the former premises. It was completed in the same distinctive sea-green finish. Everything was done to maintain continuity. All the original numbered drawers, cabinets, shelves and fittings were transferred and reinstalled. Cornelissen continues to look much like an apothecary where the early colourmen would have sourced their ingredients. It continues to stock several varieties of linseed oil, poppy oil, walnut oil and safflower oil. More than a hundred varieties of pigment are held; among the most specialised are obscure pigments known as ‘early’ colours, including genuine malachite, as used by the ancient Egyptians, and rose madder, in use since Roman times. Francis Bacon used Cornelissen’s rose madder. Ford Madox Brown and Dante Gabriel Rossetti were past customers and Damien Hirst is a customer today. As a specialist supplier, the company keeps busy in unexpected ways. It receives regular orders for bulk artist-grade titanium white from a cosmetics manufacturer, from gilders restoring icons, and dozens of sword pinstriping brushes were recently supplied to a Californian bikers’ club for the purpose of helmet decoration.

L. Cornelissen’s green frontage has been its signature for more than a hundred years.

In the calligraphy section, four different types of quills are offered.

The drawers and cabinets for canvas, parchment and paper date from the 1860s.

VISITING INFORMATION

L. Cornelissen & Son, 105A Great Russell Street, WC1B 3RY

Open 9.30am–6pm Monday–Saturday.

Truefitt & Hill

The world’s oldest barber has just five exclusive chairs. The portrait in the salon is of Naval Lieutenant, later Admiral Charles Holmes Everitt Calmady by William Pars, dating from around 1773, bewigged in the style of the day.

William Francis Truefitt opened a gentlemen’s barber shop in 1805 at 2 Cross Lane, Long Acre. By 1811 he had moved the business with its sole employee, his brother Peter, to 40 Old Bond Street, and became established as Court Hair Cutter and Court Head Dresser. He was soon also Wigmaker by Royal Appointment to His Majesty, King George III.

In the early years of the nineteenth century, when regular visits to the barber were essential to prepare the head for the wearing of wigs by gentlemen, the Truefitts’ barber shop flourished and Old Bond Street became increasingly fashionable. It may be fact or legend that the good fit of Truefitts’ wigs gave the raise to the English phrase ‘right as a trivet’, which was a corruption of Truefitt, referring to anything that was a perfect fit. The business was poised to move to the shaving of faces and the cutting of hair.

George III was destined to be the last British monarch to wear a wig, and after his death in 1820 the wig quickly disappeared from society outside the legal profession. High fashion for men was already favouring a neo-classical style of natural hair with a closely clean shaven face, as pioneered by Beau Brummel. Lord Byron and the Duke of Wellington had that style, and Truefitt was the barber to all of them. Later in the Victorian age, Gladstone was a Truefitt client and so was Oscar Wilde. Branches were established in Brighton and in Aldershot and Sandhurst, the grooming of military personnel being good business. In the high Victorian period, male fashion shifted to permit the full beard, chin-strap beard or full moustache, all requiring grooming.

Truefitt opened a ladies’ salon in Bond Street in 1870. In 1878 it started commercial manufacture and marketing of the products used in its shops. This included colognes, pomades and hair tonics. Known by this time as H.P. Truefitt, it described itself as a ladies’ and gentlemen’s hairdresser, perfumers and ornamental hair manufacturer.

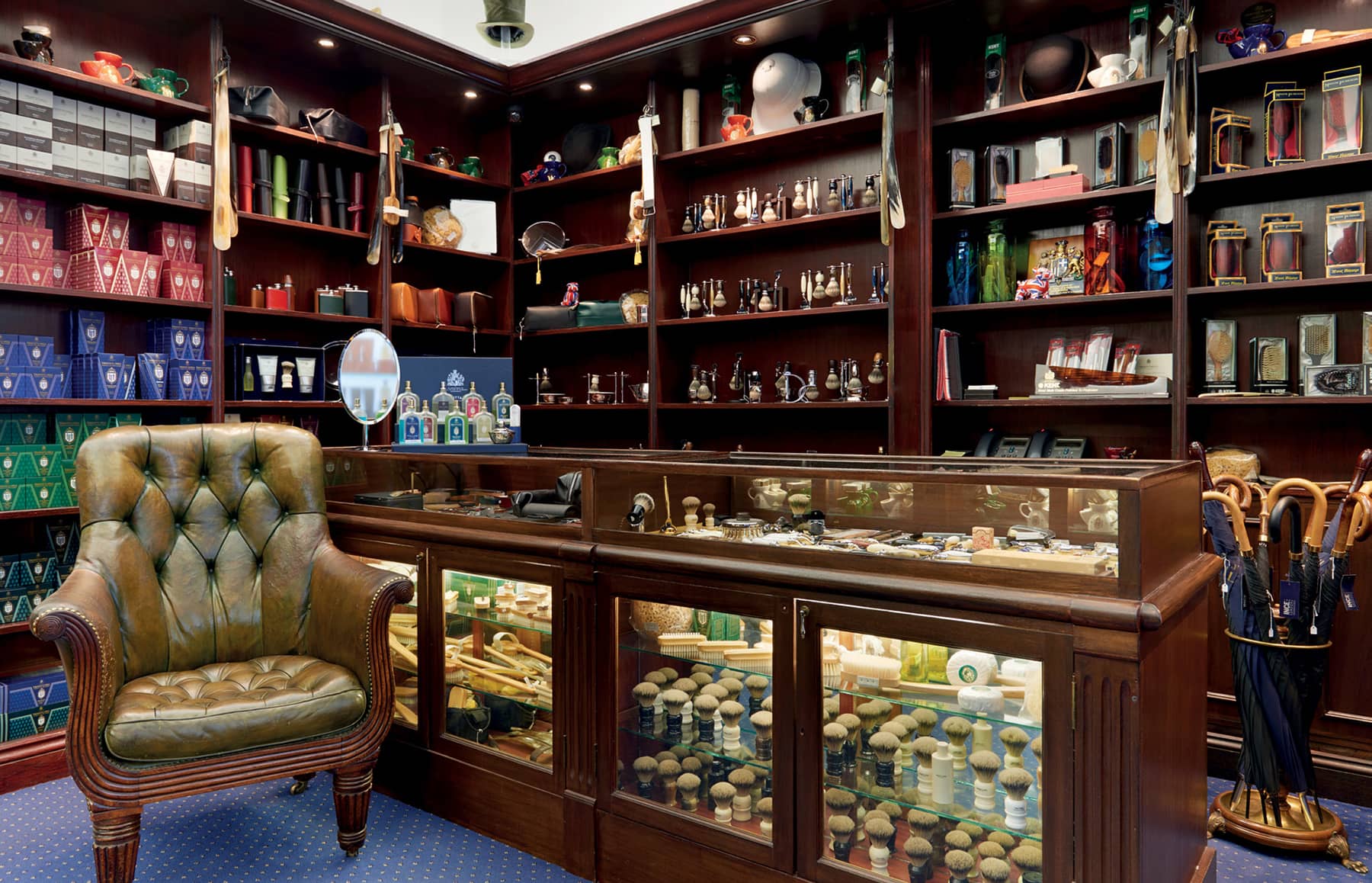

Colognes and creams in abundance at Truefitt & Hill. There are also beard combs and moustache wax.

In 1911, Edwin Hill & Co had established a barber shop close to Truefitts’ at 23 Old Bond Street. Later, a merger of the two companies was arranged and it was to this address that H.P. Truefitt moved in 1935 to form Truefitt & Hill, now specialising in hairdressing for men.

Mayfair and St James’s had become the centre of high-end masculine grooming and clothing in London, with a concentration of hair-cutting establishments and also tailors, shirtmakers and bootmakers. As well as Old Bond Street, Truefitt & Hill have been based in Grafton Street, in Burlington Arcade, and it moved to its present location of 71 St James’s Street in February 1994.

Illustrious clients in more recent times have included Laurence Olivier and visitors Fred Astaire, Cary Grant and Frank Sinatra. Another client was Field Marshal the 1st Viscount Montgomery of Alamein, who commissioned Truefitt to manufacture pairs of hairbrushes for himself and General Eisenhower, made from a piece of captured German aircraft propeller. The company has the correspondence showing that Field Marshal Montgomery received his brushes the day before the European invasion. On the same day, he wrote to Truefitt to confirm receipt and to give his assurance that he was ‘taking them all the way to Berlin’.

Having celebrated its 200th anniversary in 2005, Truefitt & Hill claims to be the oldest barber shop in the world. It is royal warrant holder as hairdresser to the Duke of Edinburgh. The company reports an increase in traditional business in London, with 25 per cent of its customers requesting a hot shave with hot towels. It has stores in Toronto, Chicago, Washington, Kuala Lumpur, Singapore, Bangkok, Mumbai, Delhi, Baku, Shanghai and Beijing.

Despite its long history, Truefitt & Hill has occupied its current premises since only 1994.

VISITING INFORMATION

Truefitt & Hill, 71 St James’s Street, SW1A 1PH

https://www.truefittandhill.co.uk

Open 8.30am–5.30pm Monday–Friday, Saturday 8.30am–5pm.

Steinway & Sons

Hall of Fame ebonised satin grand pianos; over 1,300 concert artists and ensembles are recognised as Steinway Artists.

Steinway & Sons is long established in London, the piano company first coming to England in 1875. Steinway is an American company that did much develop the piano in the middle of the nineteenth century. London piano makers had been producing instruments in quantity during the first half of the century, and Italian craftsman made pianos a hundred years before that, but it was the introduction by American makers of refinements such as the cast-iron frame and oblique stringing that set the style for the modern instrument.

Steinway opened its first London showroom in Wigmore Street, moving to St George Street in 1924 and then in the 1980s to 44 Marylebone Lane. Here are located the Steinway piano showrooms and Hall of Fame, recital room, practice facilities and administrative offices. Here can been seen the grand pianos, from a baby grand at £55,000, to a B model at £78,000, to the longest model, D-274, favoured by many of the world’s great pianists, at £132,000.

German instrument maker Heinrich Steinweg emigrated to the United States in 1850 with his family, changing their name to Steinway. Soon, he and his sons were making and selling pianos. After steady growth, and establishment of a showroom in New York, a large factory was developed in Queens. The London showroom followed and, with an eye for European markets, Steinway considered developing a piano factory in England, but the second factory was opened instead in Hamburg in 1880.

Part of the Steinway legend is how five uprights from the Hamburg factory were ordered by London and installed and lost on the RMS Titanic.

Operating in both the United States and Germany under American ownership has meant that turbulent world events have shaped the fortunes of Steinway & Sons on several occasions. The Germany factory was damaged by Allied bombing in 1944. A stock of Hamburg pianos that had been quickly shipped to Britain shortly before the war was destroyed by German bombing in 1940, together with Steinway’s Park Royal Service Centre in west London. Both the Hamburg and Queens factories were co-opted into war work on opposing sides.

The cast-iron frame is smoothed, bronzed and lacquered before the maker’s name is hand-painted.

Steinway Hall London Concerts and Artists department maintains a ‘piano bank’ of concert grands, from which artists can make their selection for upcoming performances. It also provides pianos for major institutions, competitions and recording companies in the UK. These pianos mostly come from Hamburg, although New York models can be supplied. Worldwide, the Steinway concert piano bank has over 300 instruments in use. In London pianos are serviced and restored at the centre, which opened in 1965.

It takes a year to make a Steinway grand. Spruce, sugar pine, maple, mahogany and birch are the woods employed, some of which must be left for nine months to dry and cure. Maple and mahogany are glued together in long thin sheets as veneers and then bent into the shape of a harp to form the outer case. This is clamped and stored for three months under controlled conditions. The cast-iron frame plate is the backbone of the piano and must be able to bear 20 tonnes of string tension.

Around 1,600 pianists from different musical genres are classified as Steinway Artists by the company, which means that they have chosen to perform on Steinway pianos exclusively, and each owns a Steinway. Steinway Artists include Daniel Barenboim, Harry Connick Jnr, Billy Joel, Evgeny Kissin, Diana Krall, and Lang Lang; historic Steinway Artists include Irving Berlin, Benjamin Britten, George Gershwin, Vladimir Horowitz, Cole Porter, and Sergei Rachmaninoff.

The action for a single key is made up of more than fifty parts.

VISITING INFORMATION

Steinway & Sons, Steinway Hall, 44 Marylebone Lane, W1U 2DB

Open 9am–5.30pm Monday–Friday, 11am–5pm Saturday, closed Sundays.

James Smith & Sons

Built on a tapered ground plan on the corner with Shaftesbury Avenue, James Smith & Sons is a distinctive shape and a monument to Victorian branding, with its extensive signage and packed window displays.

James Smith & Sons is one of the most distinctive shops in London, an unmistakeable landmark on New Oxford Street.

Its brass, mahogany, wrought-iron and glass exterior is emblazoned with signage, which, besides declaring umbrellas and sticks for sale, also advertises tropical sunshades, sword sticks and dagger canes. Outside and in, the James Smith & Sons store has a patina that denotes character rather than neglect. The shop has been sympathetically refurbished and it does not show. It is a thriving place that attracts thousands of visitors. The interior was designed and built by a single craftsman shopfitter. Part of the interior dates from the 1880s, when the business was already more than fifty years old. At that time, New Oxford Street was one of the most fashionable shopping streets in London and the shop design is a monument to the commercialism and branding of the era, taking every opportunity to promote and display the range. The aim was to display as many products as possible and that is still the case, with hundreds of umbrellas and sticks in baskets and racks.

For the serious purchaser of a good umbrella, the main problem is one of choice. Given the number of styles, materials and colours available there is a strong chance of creating a unique item. A crooked handle of knurled bamboo, known as whangee, fitted with a silk cover, may be considered classic. An umbrella made from a one-piece solid stick is better to lean on. The stick is cut to length to suit the user. Smooth handles may be made from cherry, chestnut, hazel or hickory, and the handle can be covered in various leathers. A lighter city umbrella can be built around a steel tube. There are styles for town and country. There are travel umbrellas, which dismantle to fit a suitcase, folding umbrellas, sun umbrellas and umbrellas with animal-head handles in wood, nickel or resin. Styles of umbrellas for ladies come in walking length or pencil length. A choice almost as wide applies to walking sticks.

Showcases and counters are original to the design of the Victorian craftsman working for Smiths.

The company was one of the first to use the famous Fox umbrella frame invented by Samuel Fox, which replaced whalebone with lightweight u-section steel ribs. This type of frame was still being produced and fitted until recently. The company says there has been little change in the design and materials of the traditional umbrella over time, apart from the fact that most covers are now made from nylon rather than silk.

James Smith founded the firm in 1830 at Foubert Place, off Regent Street. There was once a James Smith branch shop just off Savile Row, which sold umbrellas to Prime Ministers Gladstone and Bonar Law. That branch moved to New Burlington Street, but was destroyed in the Second World War. The founder’s son established the main shop in New Oxford Street in 1857.

Traditionally, umbrellas were made at the back of the shop and customers were served at the front. The tradition continues at New Oxford Street, where there are workshops in the basement. Some umbrellas and walking sticks are still made there, although sales are such that some production has to be outsourced to small family companies.

For years the company has made ceremonial umbrellas and it has produced maces for African tribal chieftains. During and after the First World War, many hundreds of thousands of military swagger sticks were sold to soldiers. James Smith once sold whips and crops. It can still supply the kind of stick known as a staff, which is associated with shepherds, and it also produces a wide range of seat sticks. One of the faded window signs even promotes ‘life preservers’: not a flotation device but a type of heavy stick suitable for use a club and no longer stocked.

Animal heads in nickel for canes or umbrellas; the straight style is called a derby, the rounded style is a crook.

VISITING INFORMATION

James Smith & Sons Ltd, Hazelwood House, 53 New Oxford Street, WC1A 1BL

Open 10am–5.45pm Mondays, Tuesday, Thursdays and Fridays; 10.30am–5.45pm Wednesdays; 10am–5.15pm Saturdays; closed Sundays.

John Lobb Ltd

The ground floor showroom displaying Royal Warrants as Bootmaker to HM Queen Elizabeth II, HRH the Duke of Edinburgh and HRH the Prince of Wales.

At Lobb a pair of shoes can cost £4,000, but it is acknowledged as representing the pinnacle of the shoemaker’s art.

The styles offered by Lobb may be recognisably classic, but the descriptions denote something special. Shoes made to the outline that most would describe as loafers can be ‘Norwegian slipper with raised lake and lace through quarters and tassels’. The Derby styles bespoke at Lobbs are curiously named ‘navvy shoes’ and it is possible to order a ‘two-tone plain golosh Oxford’. Whether you wish for calf, cordovan, patent, kangaroo, ostrich or snakeskin, Lobb advises that its extensive catalogue is merely a guide. ‘We can make any style’, the company says.

In the workrooms at St James’s, which flank the wood-panelled shop area, the ‘last-maker’ uses maple, beech or hornbeam to reflect the shape of the foot; the ‘clicker’ cuts the uppers from eight pieces of leather; and the ‘closer’, who sews, assembles the uppers around the last. The sole and heel pieces come from the misleadingly named ‘rough stuff’ department, which shapes the thicker pieces of leather. Including the ‘pattern-maker’, ‘socker’ and ‘polisher’, all the thirty-or-so craftsmen and women are apprentice-served. The first pair of shoes for a new customer will take six months or more from the moment the fitter takes the measurements to delivery; after the last has been established, subsequent orders take three months. In the shop, display cases provide a history of style in bespoke shoes.

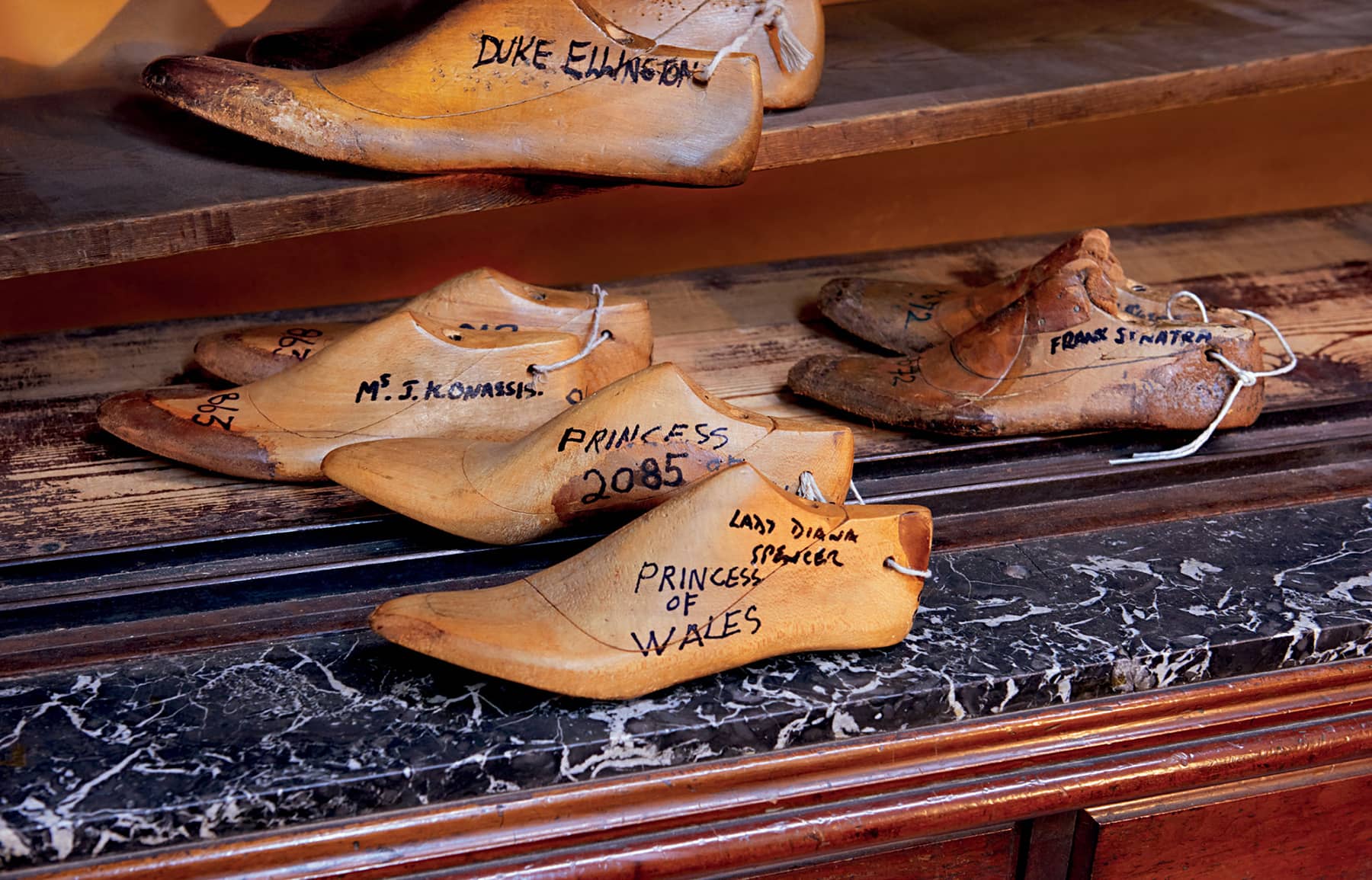

The first floor office of John Lobb has ledgers listing orders from illustrious, famous customers, and very rich customers. They list Princess Diana, Fred Astaire, Frank Sinatra and Mick Jagger. The basement houses rack upon rack of lasts, while some of them are displayed in cases in the showroom, among them the lasts for Queen Victoria from 1898 and, more recently, Duke Ellington, and Aristotle and Jacqueline Onassis.

The Lobb company history from modest beginnings to high achievement has elements of epic legend. Cornish-born John Lobb, despite being made lame by a childhood fall, walked to London in search of his bootmaking fortune. He had completed an apprenticeship to a shoemaker in Fowey, and was recognised as a good craftsman in the days before all shoes were lasted and sewn on machines. But when Lobb entered the premises of London’s leading bootmakers of the time, Thomas’s of St James’s, and offered his skills, he was ejected. Disillusioned, Lobb travelled to Australia on the strength of reports of gold being discovered and prospected for a while. He then shrewdly switched to making boots for prospectors and miners. This included a special hollow-heeled design for concealment of gold. John Lobb established a good business in Sydney. He despatched footwear to the London Exhibition of 1861, winning a gold medal, and two years later received a Royal Warrant to the Prince of Wales as bootmaker. Lobb sold up in Australia in 1866 and set up business in London. His first St James’s shop opened in 1880 alongside the fashionable hat makers, gun makers, wine merchants, tobacconists and gentlemen’s clubs of the street.

The ‘last-maker’ carves the mould.

Repairs are part of the service.

The lasts of illustrious clients – Duke Ellington, Jacqueline Onassis, Frank Sinatra and Diana, Princess of Wales.

The company has experienced turbulent times. No. 55 St James’s Street, the shop founded by John Lobb, was destroyed by bombing in 1944, forcing a move across the road to No. 26 and then in 1962, when the Economist tower block was built, the business moved again to No. 9 St James’s Street, an address once occupied by Lord Byron.

This is where the business resides today. The family continuity has remained unbroken across five generations. John Hunter Lobb is Chairman. Luxury goods manufacturer Hermès trades under the name John Lobb for some of its ranges of shoes, but the Lobb shop in St James’s Street remains in the hands of the Lobb family. There are stores today in St James’s Street where an ocean-going yacht can be commissioned or chartered, but nowhere more exclusive or truer to the spirit of that street than John Lobb, bootmaker.

Thousands of lasts are stored in the basement.

VISITING INFORMATION

John Lobb Ltd, 9 St James’s Street, SW1A 1EF

Open 9am–5.30pm Monday–Friday, 9am–4.30pm Saturday, closed Sundays.

Roof Gardens in Kensington

The Spanish Gardens have a distinctly Moorish flavour.

The Roof Gardens in Kensington are found high above the chain shops on Kensington High Street, on top of what used to be Derry & Toms department store. The gardens were created in 1938 by one of the leading landscape gardeners of the time, Ralph Hancock. Owned by Virgin Group today, the gardens have been extensively replanted and restored, but still correspond to the original plan of the three garden areas.

The ‘English Woodland’ stretches along the length of the roof with, it is claimed, almost a hundred species of trees, some dating back to the original planting. There are mosses, ferns and lichens, along with small flowering herbs and shrubs around a running brook and pond. There are resident birds, including pintail ducks and a quartet of flamingos. The ‘Spanish Garden’, inspired by the Alhambra, has a pergola known as Cloister Walk and overlooks a quiet, cool area for relaxation and rest. The lawn has a miniature canal connecting five small fountains alongside palm, olive, pomegranate and fig trees. ‘Tudor England’ has herringbone brickwork walls, stone paving and arches covered in climbing roses and wisteria.

The building’s roof was covered with bitumen, hardcore and a drainage system, so that everything could grow in soil less than a metre deep. It is now maintained on sustainable principles. Far from being a secret, but still discrete, the gardens were a celebrity rendezvous from opening and continue as an exclusive venue for events based on the Babylon restaurant.

VISITING INFORMATION

Kensington Roof Gardens, 99 Kensington High Street, W8 5SA (entrance in Derry Street)

http://www.virginlimitededition.com

Open during the day, but often closed for private events. It is essential to check before visiting: 020 7937 7994.