INNS OF COURT

The fan-vaulted undercroft of Lincoln’s Inn Chapel.

The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn

The Chapel dates back to 1620, but has seen many repairs and restorations.

London’s four Inns of Court – the Honrourable Societies of Lincoln’s Inn, Gray’s Inn, Middle Temple and Inner Temple – are the professional associations for for all barristers in England and Wales, each with a long hisory. The Lincoln’s Inn sits behind a fine brick wall on Chancery Lane, and it is easy for visitors to go inside the precincts around the squares and gardens. The group of buildings comprising Lincoln’s Inn span more than 500 years, from Tudor through Georgian to mid-Victorian Tudor Revival. To enter the main buildings – the Great Hall, Old Hall and Library – it is necessary to book a tour and set aside some time, for there is plenty of history to be unlocked.

Lincoln’s Inn began as a legal centre in around 1311, when Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln bequeathed it to London’s legal fraternity. Thomas More was a student there between 1496 and 1502. The Old Hall of Lincoln’s Inn would have been known to More, and much of the stone and brick of the fabric visible today dates from that time. The Hall was enlarged in the seventeenth century, with an internal wooden screen added. Later work was ill-judged, particularly the addition of an eighteenth-century plaster ceiling over the fine timbers supporting the roof, which together with other alterations, weakened the walls. Between 1924 and 1928 it was painstakingly rebuilt, removing the plaster barrel vault, and restoring the interior to something closer to its original appearance. The Old Hall was regularly used as a functional courtroom, notably as a court of chancery before the Royal Courts of Justice opened in 1882.

The next oldest part of Lincoln’s Inn is its Gatehouse on Chancery Lane, built between 1517 and 1521. It is a four-storey tower with diagonal lines of inky brick, and its oak gates date from 1564. It was the brainchild of Sir Thomas Lovell, a Lincoln’s Inn treasurer and veteran of the Battle of Bosworth Field, who supervised the construction, and paid the bill. Lovell’s coat of arms adorns the gatehouse, alongside those of Henry VIII, and the 3rd Earl of Lincoln, whose dragon insignia carried particular status, being rendered in purple, a costly colour in Tudor times.

Lincoln’s Inn Library is claimed to be the oldest library in continuous use in London.

In the nineteenth century, membership of Lincoln’s Inn had greatly expanded, and a new dining hall was constructed. Known as the Great Hall, or New Hall, it was designed by architect Philip Hardwick, whose initials are etched into the brickwork. The foundation stone was laid in 1843, and the hall was opened two years later by Queen Victoria. It incorporated a new main entrance gatehouse on Serle Street. Dominating the north wall of the hall is a vast fresco whose title is Justice, by George Frederic Watts, with depictions including Moses and Confucius, while Norman Hepple’s oil painting Short Adjournment is a tribute to an era when the majority of Court of Appeal judges were Lincoln’s Inn members.

The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn claims that its collection of books is the oldest library in continuous use in London. Lincoln’s Inn Library was first mentioned in 1471. The present library building, an iron-galleried masterpiece, is part of the mid-nineteenth-century building works. It contains 150,000 volumes. As well as housing a unique collection of rare books, it is also a functioning modern legal library, and the only Inns of Court library to survive Second World War bombing.

Stone Buildings, a set of lawyers offices known as chambers, was constructed during the 1770s in the distinct style of the time, contrasting with the red brick elsewhere. Although Lincoln’s Inn was more fortunate than the other Inns of Court during the war, Stone Buildings was hit and badly damaged, and this damage was subsequently repaired. A rare London relic is a remaining mark of the first Blitz, as the front of No. 10 Stone Buildings still shows considerable damage inflicted during an air raid of December 1917. A disc, set into the road outside, marks the spot where the bomb exploded.

An early Lincoln’s Inn Chapel is first mentioned in records from the reign of Henry VI; the foundation stone of its successor was laid by John Donne, poet and priest, and Preacher of Lincoln’s around 1620. The stained glass in the south window pictures the Apostles, and is attributed to the Van Linge brothers. The chapel also displays colours of the Inns of Court Regiment. The vast space of the Chapel’s seventeenth-century fan-vaulted undercroft, where benchers and members were once laid to rest, is a place where today’s bewigged and gowned barristers pause to chat.

The Great Hall, or New Hall, designed by Philip Hardwick, was opened by Queen Victoria on 30 October 1845.

The Chapel bell, which is tolled at noon whenever a bencher dies, was reputedly immortalised by John Donne in the line ‘therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee’. Harder still to prove is the legend that playwright Ben Jonson worked as a young man as a bricklayer on the wall and gatehouse, but Lincoln’s Inn does not need to scratch around for history. Notable members have included Walpole, Pitt the Younger, Gladstone, and Margaret Thatcher, fifteen Prime Ministers in all.

The Old Hall was used as a functioning courtroom.

Portraits and crests adorn the walls of the Great Hall.

VISITING INFORMATION

The Honourable Society of Lincoln’s Inn, WC2A 3TL

Precincts open 7am–7pm Monday–Friday.

For tours of the buildings, email gina.roberts@lincolnsinn.org.uk.

The Honourable Society of Gray’s Inn

The high table stands at the eastern end of Hall.

The Honourable Society of Gray’s Inn, on the busy intersection of Gray’s Inn Road and High Holborn, is the smallest Inn of Court. The main buildings form two squares – Gray’s Inn Square and South Square – with other ranges to the west and north round the gardens, known as the Walks. Its origins lie in an estate and manor owned by Reginald de Grey (or de Gray). A close friend of Edward I, soldier, judge and High Sheriff of Nottingham, he was a scion of a noble family of power brokers. At some point, no later than 1370, the de Grey family leased the estate’s manor house to lawyers, who lodged and educated students, and the Honourable Society of Gray’s Inn came into being.

As medieval England passed into the golden age of Elizabeth I, Gray’s Inn thrived. Members included William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, Elizabeth’s chief advisor, Francis Walsingham, her spymaster, and Lord Howard of Effingham, the Lord High Admiral and victor of the Spanish Armada. Queen Elizabeth herself was a patron. As the favoured Inn of her court, it was strongly politicised. Diego Guzmán de Silva, Spanish ambassador to Elizabeth’s court, saw Gray’s Inn as a pit of anti-Catholic sentiment.

It was also a place of learning. Nicholas Bacon, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, along with Francis, his son, a renowned scientist, statesman and jurist, were leading members. Another member, Henry Wriothesley, 3rd Earl of Southampton, gave patronage that enabled the promising young William Shakespeare to flourish as playwright and actor. Indeed, the Inn hosted an early, possibly the first, performance of The Comedy of Errors in Hall on 28 December 1594, at which Shakespeare himself may have been present.

The heart of Gray’s Inn lies in its red brick Hall, on the site of the old manor house. The earliest surviving record of it mentions reconstruction and refurbishment between 1556 and 1560 at a cost of £863. A panelled chamber used as a ceremonial centre and refectory, ‘Hall’ (as it is known) is crowned by a hammer-beam roof described as ‘the most spectacular endeavour of the English medieval carpenter’. The vaulted gothic woodwork of its main body stands in contrast to a massive ground-level wooden screen of carved chestnut, reputedly a relic from a captured galleon of the Spanish Armada. At the top end of Hall, standing upon a dais, is a vast oak dining table, whose dark wood is illuminated by stained-glass windows, one dated 1462, emblazoned with the arms of Burghley, Bacon and many others, while the walls carry portraits of Elizabeth I, Nicholas Bacon and others, and wooden panels displaying the arms of Treasurers.

The benchers’ entrance of Hall.

While Gray’s Inn Hall survived the religious turbulence of the sixteenth and earlier seventeenth centuries, the Inn underwent a prolonged period of decline. In the late-seventeenth century it suffered three disastrous fires, one of which destroyed the library. At this time, qualification for the Bar depended on eating a number of dinners in Hall and the recommendation of a judge. Standards were finally raised in the nineteenth century and the Call to the Bar examination was introduced in 1872.

The Hall and other buildings in Gray’s Inn Square and South Square were almost wholly burnt out in the massive incendiary attack of 10–11 May 1941, the final night of the Big Blitz. The paintings, stained glass and heraldic panels had already been moved to a place of safety, but the Armada Screen, although it had been dismantled for moving, remained in the Hall. Firemen braved falling timbers and molten lead to drag the sections to safety. After the end of the war, a new Hall, designed by Edward Maufe, architect of Guildford Cathedral, was opened by the then Duke of Gloucester in 1951, and Maufe was elected an Honorary Bencher.

The Armada Screen in Hall, reportedly carved from a captured Spanish galleon.

Gray’s Inn Chapel stands where a place of worship has existed since at least the reign of Edward II. By 1539, with the Reformation in full swing, Pension (the governing body of Gray’s Inn) removed the stained glass image of Thomas à Becket from the Chapel windows, out of obedience to Henry VIII. The Chapel was rebuilt during the late seventeenth century. In 1893, the building was restored in the late gothic style, but destroyed by enemy action in 1941. The present building is also to the design of Edward Maufe, and contains an east window celebrating the lives of four archbishops, members or preachers of Gray’s Inn, namely, Whitgift, Juxon, Laud and Wake, with, in less fractious times, Becket restored.

VISITING INFORMATION

The Honourable Society of Gray’s Inn, 8 South Square, WC1R 5ET

Open 6am–8pm Monday–Friday; gardens open 12pm–2.30pm Monday–Friday.

Tours of the buildings are available through Open House London:

The Honourable Society of the Middle Temple

Carved coats of arms and portraits of members and barristers of the Middle Temple.

A walk south from where Strand meets Fleet Street takes a visitor through some of the most pleasing and peaceful territory in London – the Temple – comprising two Inns of Court and an ancient church. The division between the Inner Temple and Middle Temple runs along Middle Temple Lane. Temple Church belongs to and is maintained by both these honourable Societies. Courtyards of the Inn grounds are open during the day for varying periods during the year. This is at the discretion of the individual Inn, as the precincts are classified as private with public access, but it is generally possible to walk through at reasonable times. To visit the buildings of these Inns of Court, it is necessary to pre-book a tour.

The Temple was once a headquarters of the English Knights Templar, and lawyers associated with the Knights had occupied parts of the area. That organisation was dissolved in 1312, and rights to the Temple devolved on to the Knights Hospitaller, who were in turn closed down by Henry VIII in the Reformation. The barristers remained and gained the tenure of Temple from a charter granted by James I in 1608.

The charter gave sole use of the land to house and educate lawyers and preserved some privileges inherited from the Knights Templar, including independence from neighbouring authorities. This still applies in the twenty-first century, enabling both Temples to enjoy the unique status of extra-parochial area, functioning as a local authority outside the City of London’s civil jurisdiction and outside the Bishop of London’s ecclesiastical authority.

Although occupying the same space, it seems that the two Inns were distinct bodies long before formal separation in 1732, and it is possible to see either the Middle Temple’s Lamb and Flag emblem or the Inner Temple’s winged horse Pegasus at various places around the courts.

The Lamb and Flag is the emblem of the Middle Temple.

The Inns survived the Civil War in England, having members on both sides of the conflict, but legal education fell into abeyance when Middle Temple closed for four years. The buildings of the Middle Temple were spared London’s Great Fire in 1666. The fire abated just yards to the east.

A number of idealistic Middle Temple barristers sailed to the Americas in search of Arcadia, five of them signing the American Declaration of Independence. In the twentieth century, women were first called to the Bar of England and Wales, including Barbara Calvert, first female head of chambers, and Patricia Scotland, first female Attorney-General.

Hammer-beam ceilings attract much attention in architectural guides, and Middle Temple Hall possesses an example that is particularly impressive. Short straight beams and curved collarbeams are stepped up into the roof. This process is repeated, making it a visually complex double-hammer-beam, giving greater height, and generating a greater sense of space. It supports the claim that Middle Temple is the finest Elizabethan hall in England.

Dating from 1562, Middle Temple Hall lies in the heart of the Inn. Historical fact and legend rub shoulders here. There is solid evidence that Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night was performed in Hall on 2 February 1602, most likely its premiere. Less certain is the legend attached to the high table, which is reputedly a gift from Elizabeth I. It was constructed from twenty-or-so oak planks cut from a single oak in Windsor Great Park, and floated down the Thames. Still in use today, it was in place in 1586, when a triumphant Francis Drake, flushed with success in the Spanish West Indies and North America, was cheered in Hall by the benchers and members. The Golden Hind’s hatch cover is said to have been used to construct what is called the ‘present’ cupboard, a table standing below the benchers’ table, on which rests the book signed by barristers newly called to the Bar. As with the other Inns of Court, Hall’s windows commemorate famous members, who include the explorer Raleigh, while panelled walls are adorned with members’ coats of arms dating from 1597.

The libary, displaying its prized Elizabethan globes.

A Tudor library once existed here, but its shelves were reduced by theft. Re-established in the seventeenth century as a chained library, the collection grew to include 250,000 textbooks, law reports, journals and parliamentary papers, plus volumes on topography, geography and theology, and a 1571 biography of Columbus penned by his son. In 1861, Edward, Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, opened a new library building in 1861, but this was damaged beyond repair in the Second World War. Sir Edward Maufe, architect of Guildford Cathedral, designed the current library, completed in 1958.

The library today displays on its upper floor two Elizabethan globes, by Emery Molyneux, possibly the first to be made in England. One is the terrestrial and the other celestial. They were based on the most accurate mappings and projections of the day and the terrestrial globe was updated in 1603 to include the latest discoveries of Raleigh.

VISITING INFORMATION

Middle Temple Hall, Middle Temple Lane, EC4Y 9AT

http://www.middletemplehall.org.uk

The grounds are open to the public. Tours of the buildings may be booked online.

The Honourable Society of the Inner Temple

The Inner Temple Hall is one of the very few Georgian-style banqueting halls in the City of London.

There is a marvellous feeling of enclosure about the Inner Temple, which is completely hidden behind Fleet Street and separated from the noisy Victoria Embankment by an extensive garden. Although this Inn of Court has two distinct gateways, according to tradition its main entrance has always been on Fleet Street. It is easy to miss the archway under a Jacobean house at No. 17. The house does not belong to the Inn, but the pathway does, and it leads first to Temple Church and then opens out to the Inner Temple.

While the buildings of the Honourable Society of the Inner Temple today carry a powerful sense of history, the relatively pristine look of much of the fabric needs explanation. Most of the Inner Temple comprises post-Second World War buildings or structures, described as reinstatements. A bomb damage map compiled by London County Council between 1940 and 1945 shows more than half the array of Inner Temple’s buildings marked purple, meaning ‘damaged beyond repair’ and most of the others denoted in red as ‘seriously damaged, doubtful if repairable’. Over a period of four years its buildings had suffered hits from high-explosive incendiaries and blast damage from a V-1 flying bomb; rebuilding took thirteen years.

A senior former bencher has described the Inn of the 1930s as ‘grubby, sooty . . . marvellous Victorian buildings’, with certain small courtyards now disappeared. The changes before then and since have been numerous, and the precise antiquity of buildings should perhaps be set aside. In the nineteenth century, much of Inner Temple had been rebuilt. By then, the Hall was an 1870 gothic design, with stained glass showing episodes of English history, and a huge window depicted Queen Victoria surrounded by four Virtues representing Government and Law. At the west end of Hall, two Elizabethan doors, supposedly remnants of a carved screen erected in 1574, stood beside bronze statues of Knights Templar and Hospitaller. Nearly everything of the Hall and its contents was destroyed in 1941. At the west end, an old buttery and a crypt with a fifteenth-century fireplace survive from a much earlier structure, the oldest part of the Temple.

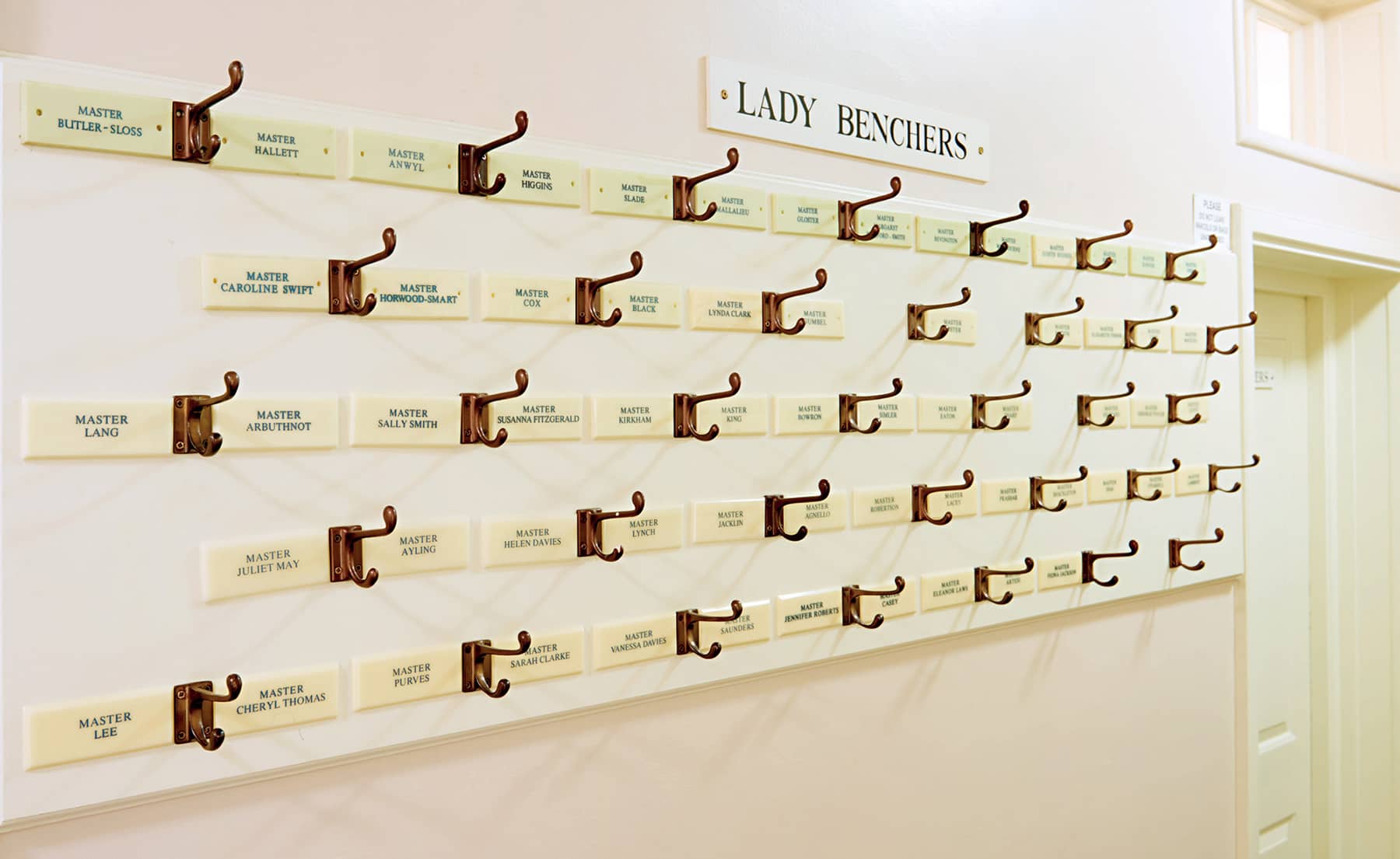

Robing hooks inside the benchers’ entrance at Inner Temple. Lady members who are benchers are still known as ‘Master’.

The foundation stone of the modern Hall, designed by Hubert Worthington, was laid by Queen Elizabeth II in 1952 and opened in 1955.

It was not until 1958 that a new library was completed to a design in the style of an eighteenth-century room. An earlier library had burned down in the Great Fire of 1666. It was quickly replaced but this had to be destroyed by explosives in 1678 during another fire in order to prevent destruction from spreading throughout the Temple. In 1828 a gothic library followed.

Celebrated members of the Inner Temple who studied in those libraries included Edward Coke, the great Elizabethan/Jacobean jurist, the advocate Sir Edward Marshall Hall, who saved many from the noose, Lord Rayner Goddard, famously in favour of hanging and corporal punishment, Lord Justice Birkett, a presiding judge at Nuremberg, British Prime Ministers Clement Attlee and George Grenville, with India represented by Gandi (disbarred 1922, reinstated 1988), and Nehru.

To the south of the Inner Temple lies a 3-acre garden, with lawns, herbaceous borders and a collection of rare trees. The garden area was extended when the Thames was pushed back by the new Victoria Embankment in 1870. The Royal Horticultural Society Great Spring Show was first held here from 1888 before switching to its current site at Chelsea Hospital in 1913.

The Parliament Chamber.

A secret ballot box, adorned with the Pegasus emblem of the Inner Temple.

VISITING INFORMATION

The Inner Temple, EC4Y 7HL

Open 9am–5pm Monday–Friday; gardens open 12.30pm–3pm Monday–Friday.

Tours of the buildings for groups of at least five may be booked by email: visits@innertemple.org.uk.

Temple Church

‘The round’ is the oldest part of the Temple Church.

The Temple Church, with all its facets of history, symbolism and myth, surprises visitors today with its well-lit simplicity. It was built to the round design of Jerusalem’s sixth-century domed Byzantine Church of the Holy Sepulchre, faithful to the tradition of the Order of the Knights Templar. Circularnaved churches are rare in the British Isles, although not all round churches are associated with military orders. The Temple Church was consecrated in 1185 in the presence of Henry II, England’s first Angevin king. It comprises two distinct parts: the original circular building, known as ‘the round’, which is now the nave, and the rectangular addition on its eastern side, now the chancel, built half a century later, in 1240. The round church, some 55 feet (17m) in diameter, accommodates a circle of Purbeck marble columns. It is likely both Temple Church’s walls and gargoyles were initially painted in bright colours.

Temple and its Church were commandeered between 1214–15 by King John – who was then in conflict with both the Pope and the Barons of England – for use as a government office. It was here that he was confronted by the Barons and compelled to ride to Runnymede, where he signed the Magna Carta. William Marshal, 1st Earl of Pembroke, reissued Magna Carta after John’s death to ensure its survival, before being laid to rest here in Temple Church.

During the era of Templar initiation ceremonies, new recruits entered the west door of the round church at dawn, and swore vows of piety, chastity, poverty and obedience to the order. Some of the strangeness and secrecy attached to these Templar ceremonies became the source of interest when an inquisition was launched, contributing in part to its downfall. In 1307, Pope Clement V ordered Christian monarchs to arrest the Templars across Europe and to seize their assets, leading to Edward II’s control of Temple Church before its transfer to the rival organisation the Knights Hospitaller, and then reversion to the Crown in 1540.

In the 1580s, Temple Church played out the stresses within the Church during what was called the ‘Battle of the Pulpits’. Master Richard Hooker preached his Gospel interpretation, a moderate fusion of Anglican/Catholic tenets, whereas Reader Walter Travers took up the austere ideals of Calvin, causing one observer to comment: ‘If Canterbury was preached in the morning, come afternoon it was contradicted by Geneva [the headquarters of Protestant reformation].’

Although it was spared serious damage in the Great Fire of 1666 – the maximum westerly spread of the blaze just touched Temple Church – it did receive some revisions by Christopher Wren, including a fine carved altar screen. There were plans to introduce an organ for the first time, but the two Inns of Court could not agree which design of organ to install, and two trial instruments were built. Many organists, including George Frederic Handel, played on them.

The controversy resulted in deadlock and it was decided the choice should be made by the Lord Chancellor, the notorious Judge Jeffreys. Jeffreys, a member of Inner Temple, diplomatically chose the organ designed by Father Smith, favoured by the Middle Temple. Even if honour was satisfied, each of the Inns continued to appoint their own organist for nearly a hundred years until 1814.

The church underwent further restoration in 1841, under direction of architects Sydney Smirke and Decimus Burton, who decorated the walls and ceiling in high Victorian gothic style. Exactly one hundred years later, incendiary bombs set the round church’s roof ablaze, with the organ and internal wooden sections destroyed, and the Purbeck marble columns in the chancel cracked in the searing heat.

The church was rededicated in 1958. Much has been changed or restored over 830 years, but the title of the chief priest remains the Reverend and Valiant Master of the Temple. At Temple Church, the distinctive ground plan has endured and much of the porch of the Norman west door is original stone.

The chancel is a later addition to ‘the round’ nave, dating from the early thirteenth century.

The monument to William Marshall, 1st Earl of Pembroke (left), and the 2nd Earl (right).

An exceptional stroke of luck enabled the architects of the 1945–58 restoration, Walter and Emil Godfrey, to use the carved reredos designed by Wren (and executed by carver William Emmett). Removed by the Victorian restorers and salvaged, the screen had spent over one hundred years in a museum in County Durham, and it was possible to recover it and refit it in its original position. The marble columns in the round were replaced to their original shape after 1945; their authenticity includes a curious outward lean.

A visitor entering through the south door sees nine marble effigies of martial figures lying on the floor of the round; these include William Marshal, Geoffrey de Mandeville and Robert de Ros, dating from 1227. With the extensive reworking over centuries, these effigies are best understood as monuments rather than as marking tombs, although the men represented were interred nearby. The visible damage to the figures mostly dates from the Blitz, relatively recently restored.

The east window, a gift from the Glaziers’ Company in 1954 to replace glass destroyed in the war, shows Christ’s connection with the Temple at Jerusalem. In one panel he talks with the learned teachers, in another he ejects the money-changers. The window also pictures some of the people associated with Temple Church over the centuries, including Henry II, Henry III and several of the medieval Masters.

VISITING INFORMATION

Temple Church, Temple, EC4Y 7BB

Open weekdays only. Check online for times and entrance fees.

Stained glass and altar at the eastern end of the church.

The restored altar screen was designed by Sir Christopher Wren.