JOHN HENRY had an impulse to grab the Swiss Army knife he’d given Tim and use the saw blade on the fingers that had painted the warts and mustache on Tim’s portrait. Why had he done such a rotten thing to his brother—his one and only brother? It was a hard question to figure out the answer to. But as he squinted at the snowy landscape outside the window and pictured Tim tromping along without his parka and snow boots, he did figure out one thing. Finding his brother would be better than sawing off his fingers.

He turned off the oven—the turkey was getting awfully brown—and wrote his parents a note. Then he put on his own snow boots and parka and his wool cap and deerskin gloves.

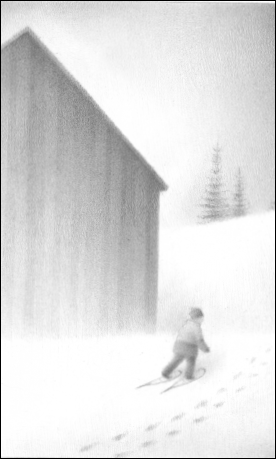

The first place he went was the shed, in case Tim was hiding behind the woodpile or in the canoe up in the rafters. He wasn’t. So John Henry set off down the road.

About a hundred yards before he reached the Cooleys’ driveway, he spotted a trail of footprints zigzagging across one of their pastures—toward the foot of Great-aunt Winifred’s hill. He climbed the snowy stone wall and followed the tracks. But the drifts of new snow made the going slow, and he soon veered off toward the Cooleys’ barn. The cows were mooing like crazy. Christmas must have delayed their second milking. He slipped in the side door, into the pump room. This was by far the cleanest corner of the barn—it housed two shiny steel vats where the milk was stored till the truck came to pump it out—but even there the cow stench was so thick, you could smell it even when you held your breath. John Henry took down a pair of snowshoes hanging on the wall between a two-man saw and an old leather harness. The Cooleys wouldn’t mind him borrowing them.

The snowshoes made slogging along a little easier, and the trail of footprints soon led him up into the woods. The snow wasn’t so deep there, the branches overhead having caught a lot of it—which was probably why Tim hadn’t used the road. Tim’s trail weaved back and forth, as if he’d gotten tired, but once John Henry reached the hilltop and rounded the garage, he saw that the tracks led up Great-aunt Winifred’s front porch steps and finally stopped to catch his breath, knowing his brother must be safe. Spread out before him was the famous view. The sun was setting, blood red behind the snow-white hills, and as he took it in, he wondered for a moment how Tim would see it if he was sitting at his easel. Tim’s paintings were pretty good. Would Tim see more than he did? In spite of how cold the sewing room had been last night, and in spite of the fact that he’d just been sticking on warts and a mustache, there had been a curiously pleasant feeling of power in applying the paint.

The wind chimes tinkled as a blast of wind swept over the hilltop. John Henry kicked off the snow-shoes and climbed the front porch steps. The front door was unlocked, but when he stepped into the house, it was as cold as a tomb. He flicked a switch, and the dusty old crystal chandelier in the front hall came on.

“Timmy?” he yelled, seeing his breath.

No answer. He called up the front stairs. No answer. He went through the entire house, flicking on lights upstairs and down, finally even checking the basement. Down there he found a shelf of forgotten Mason jars containing Great-aunt Winifred’s applesauce and blackberry preserves. But there was no sign of his brother.

Back up in the kitchen John Henry heard a scratching at the back door. He opened it and caught sight of a porcupine scuttling off under a holly bush, leaving a thin trail in the backyard snow. Parallel to it was a bigger trail, made by a person.

The guilty feeling clawed at John Henry’s throat again. Tim would never be able to make it all the way home—and besides, it was getting darker by the minute. John Henry picked up the kitchen phone to call 911. There was no dial tone. Either the lines on the hillside were down or his father had had the phone disconnected.

Trying not to panic, John Henry ransacked the kitchen drawers. But when he finally found a flashlight, the batteries in it were dead. Everything about the house seemed creepy and cold and dead.

John Henry pulled his gloves on and hustled out the front door. He put the snowshoes back on and clumped around to the back of the house. Tim’s tracks led him into the woods. The trail zigzagged among the pines and spruces and birches like a drunkard’s.

It wasn’t even four o’clock, but the last daylight was already dying, and as it did, the temperature seemed to dip another ten degrees. In a way this was a help. A crust formed on top of the snow so that John Henry’s snowshoes didn’t break through at all, making it easier to walk. But the trail was leading down the far side of the hill, away from everything he knew. And it was getting so dark, he had to bend over to make out the tracks.

At last they led out of the woods into a big clearing. Visibility was a bit better there, for a sliver of moon had risen, but it was still hard to follow the trail—and the trail was more crooked than ever. In fact, it was completely crazy, doubling back on itself here, going in circles there, leading him back over places he’d just been a minute earlier.

Then he saw a dark heap in the snow up ahead.

“Timmy!” he cried, breaking into a clumsy run.

The heap was definitely his brother, curled up on top of the crust. His shoes and jeans were dark, his socks and ski sweater and a funny old knit hat of Great-aunt Winifred’s all sugarcoated with snow. John Henry kicked off his snowshoes and sat down on the crust and put Tim’s head in his lap. He pulled off his gloves and wiped the snow from Tim’s face.

“Tim? Are you okay?”

When Tim opened his eyes in the moonlight, John Henry stopped feeling cold for a moment.

“Thank goodness!” he said. “But why’d you leave Aunt Winnie’s?”

Although Tim’s eyes were open, they seemed to be glazed over. “She’s dead,” he whispered.

“Course she’s dead. She’s been dead for three months. Hey, where’d you get this bump? It’s big as a quail egg.”

Tim’s eyes closed.

“What’s with you, man?” John Henry cried.

“Listen, I’ve got to tell you something.” John Henry shook Tim till his eyes reopened. “It was me put on those warts and stuff—late last night. I’m really, really sorry. I don’t know what got into me. When I saw the painting you made of me, I wanted to croak.”

Tim blinked once.

“Do you forgive me?” John Henry asked.

Tim said something, but too quietly to hear.

“Huh?” said John Henry, leaning closer. “You forgive me?”

“For ruining my painting?” Tim said. “Or for making Mom and Dad think that’s how I see them?”

John Henry swallowed. “Both?” he suggested, his own voice dropping to a whisper.

Tim looked at him in a way that made John Henry wonder again if painters saw more than ordinary people when they looked at something. But Tim said nothing, and after a few moments his eyes closed again.

“Hey!” John Henry shook him once more. “Can you get up?”

The eyes reopened.

“Come on, we’ve got to get back to Aunt Winnie’s. We can make a fire in the stove.”

“She’s dead,” Tim mumbled.

“Yeah, she’s dead. But you still got me. And Mom and Dad. Come on.”

John Henry shook him some more, but this time the eyelids stayed shut. He brushed the snow off Tim’s sweater, took off his own parka, and put it on his brother. But Tim still remained out.

“God,” John Henry groaned. “How am I going to get you back up to the house if you keep dozing off on me?”

The funny thing was, though, that he was feeling kind of drowsy himself. It seemed crazy, considering his long nap—though the narrator of the Mount Everest special had said something about intense cold making you sleepy. And hadn’t he said something about how you were supposed to fight it?

A gust of icy wind swept across the clearing and cut right through to his bones. All he had on now was three layers—T-shirt, shirt, sweater—and for a moment the chill made him feel all too wide-awake. Struggling to his feet, he put his hands in his brother’s armpits and started dragging him up the hill. By the time they’d gone ten yards—one lousy first down—John Henry was gasping.