A ROMAN EMPEROR HAD TO COMBINE CHARISMA AND superb generalship with administrative brilliance. The challenge was how to present himself as a focus for the many local cultures of an empire which stretched from the Irish Sea in the west to the Euphrates in the east. If he lost the allegiance of local elites, things could easily fall apart, provinces break away and the borders crumble under the weight of invaders. It was a task that called for enormous self-confidence, and the empire was especially lucky in its emperors in the late third and early fourth centuries. First there was Diocletian (emperor from 284 until his abdication in 305), who, after decades of corrosive barbarian attacks which almost destroyed the empire, reorganized its administration and finances and developed more flexible methods of defence. Then there was Constantine, who clawed his way to power through a succession of military victories, one of which, the battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312, gave him supremacy in the western empire. This victory, he claimed, was due to the support of the Christian God; he responded by extending toleration and patronage to Christians, so setting the religion on its way to dominance in the Mediterranean and eventually far beyond.

After he had fought his way to power in the eastern empire as well, Constantine founded a new eastern capital, Constantinople, which was dedicated in 330. It was to become the capital of two later empires, the Byzantine and the Ottoman, the second of which survived into the twentieth century. It was an extraordinary achievement and its endurance was largely the result of Constantine’s own political genius. Not only was he virtually unbeaten as a general, he recognised the importance of following conquest with reconciliation between the victors and the defeated. In order to achieve consensus and good order amoung his peoples, Constantine became adept at maintaining the mystique of monarchy through the manipulation of traditional symbols of imperial rule.

The emperor Constantine. As is typical of portraits of emperors of this period, the face is idealized to suggest the emperor’s semi-divine nature. (Ancient Art & Architecture Collection)

The image Constantine used more than any other was that of the sun, whose provision of the warmth and light vital to human existence had long made it a popular symbol among both philosophers and spiritual leaders. Plato had used it to represent ‘the Good’, the value which surpassed all others. Apollo, the god of reason and balance, had the sun as one of his emblems. A cult of Sol Invictus, ‘the unconquered sun’, originally imported from Syria, was very popular among Roman soldiers. A practice of representing the emperor as a sun-god seems to have come into the Roman world via the royal family of Commagene in eastern Anatolia, whose kingdom had been absorbed into the empire in the first century AD. The annexation had been a peaceful one and the Romans maintained good relations with the last king, Antiochus IV, who had been brought back to Rome and treated with respect there. One of Antiochus’ grandsons, Philopappus, had been appointed to the ancient post of consul by the emperor Trajan for the year 109 and then made an honorary magistrate in Athens. In Commagenian tradition the king was associated with the sun, and when Philopappus had himself depicted on the monumental tomb he built for himself in Athens he was shown in a four-horse chariot, with rays coming from his head and his right arm raised, as was usual in depictions of the sun-god Sol. The emperors appear to have adopted the theme. By AD 170 the reliefs on the famous Antonine altar from Ephesus (now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna), which glorify the Roman emperors as saviours of the east, show a second-century emperor, possibly Trajan, ascending to heaven in a chariot of the sun. By the third century emperors such as Caracalla (AD 211–17) were portraying themselves as the sun itself driving a four-horse chariot.

Constantine followed in this tradition, as one can see in the triumphal arch built in his honour by the Roman Senate in AD 315, which still stands beside the Colosseum in Rome. In reliefs specially designed for the arch, Constantine is shown making his adventus, his ceremonial entry, into Rome after his defeat of Maxentius at the battle of the Milvian Bridge. The emperor is seated in a golden carriage drawn by four horses. On a roundel just above the relief and clearly associated with it, Sol is shown rising, also in a four-horse chariot. An even more precise link between Constantine and the sun is established by a medallion dated to 313, the year after the battle of the Milvian Bridge: here a wreathed Constantine, alongside a radiate Sol, bears a shield on which, again, there appears the sun being carried upwards in a chariot drawn by four horses.

Yet despite these openly pagan allegiances, Constantine was also seen by the growing Christian community as one of their own. Historians disagree as to whether Constantine was a committed Christian himself or whether his main concern was a political one, to use the church with its well-established hierarchy of bishops in the service of the empire. In any case, as a traditional Roman, Constantine may have believed that he could follow a variety of cults without impropriety; in other words, association with Christians did not mean he had to abandon other cults. He was not even baptized until the very the end of his life. One reason why he could honour the cult of Sol without offending Christians was that the sun had also been integrated into Christian worship. There is an early fresco in Rome of Christ ascending into heaven in the chariot of the sun-god, and the cult day of Sol Invictus was none other than 25 December, the date Christians were to adopt as the birthday of Christ. There is even a record of Christians in the fifth century worshipping the rising sun from the steps of St Peter’s in Rome (to the intense annoyance of Pope Leo the Great, who had hoped they had moved on from such things). Certainly the bishops were quite satisfied by Constantine’s support. One, Eusebius of Caesarea, even wrote a panegyrical life of the emperor in which he made an unlikely analogy between Constantine and Moses.

The triumphal arch erected in Rome in 315 in celebration of Constantine’s conquest of the city in 312. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

These reliefs from the arch show Constantine making his triumphal entry into Rome, appropriately in a four-horse chariot, with, on the roundel, his symbol the sun, ascending heavenwards on a similar chariot. (The Art Archive)

Sol, the Roman sun-god, was always associated with four-horse chariots and is depicted here in a Roman mosaic. (Ancient Art & Architecture Collection)

Constantine’s presentation of himself as a sun-god was matched by other trappings of divinity through which he kept his distance from his subjects. He was never addressed directly by his name, but by an abstraction such as Your Majesty or Your Serenity. Great audience halls were built inside the imperial palaces, their walls lined with varied marbles or shimmering mosaics. (One still stands in Trier in Germany, although it has long since been stripped of its fittings.) Suppliants had to bow before him, presenting their petitions with extravagant formality; the emperor’s reply would be passed down through a hierarchy of officials. He was dressed to impress, in purple, a hue produced by a dye which was extracted in tiny quantities from molluscs and so prohibitively expensive. We read of one council of bishops, held in the audience hall of the imperial palace in Nicaea, where Constantine appeared among them ‘like some heavenly angel of God, his bright mantle shedding lustre like beams of light, shining with the fiery radiance of a purple robe, and decorated with the dazzling brilliance of gold and precious stones’. Those who beheld him were said to be ‘stunned and amazed at the sight – like children who have seen a frightening apparition’.

Constantine’s foundation of Constantinople on the Hellespont, the strait which ran between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, fits well with this policy of keeping himself above his subjects. From a strategic point of view the ancient Greek city of Byzantium was an excellent choice. It was on the junction of major routes between east and west, and also relatively close to the Danube and Euphrates rivers, borders of the empire which were often under threat. Its position on a promontory meant that it could be walled off and so virtually impregnable, as invaders were to find throughout the city’s history. Philip of Macedon, a master of sieges, had failed to capture it in 340 BC and an earlier Roman emperor, Septimius Severus, had taken two years to subdue it at the end of the second century AD. So here was Constantine at his most pragmatic; but by choosing a relatively remote site, the emperor was also able to maintain his elevated status. As a man whose family originated in the Balkans, he would never have been fully accepted by the ancient senatorial families of Rome. In Byzantium, on the other hand, Constantine was left free to craft his own foundation – and he did not even have to compromise with the church. Byzantium had very little in the way of a Christian heritage when Constantine began expanding it into a capital in the 320s. Even then the building of churches was given low priority and the dedications of those planned for the city were to Divine Peace and Divine Wisdom (the famous church of Santa Sophia, still standing in its rebuilt sixth-century form), dedications which would cause no offence to pagans. The only specifically Christian building which had been completed by the time of Constantine’s death was the Church of the Holy Apostles but as the emperor chose to be buried in it as the ‘thirteenth apostle’, with sepulchres representing the original apostles grouped around him, this was in effect a church dedicated to himself. Constantinople, as its name suggests, was a showcase city for the glorification of the emperor.

An audience hall could hold only a limited number and an emperor like Constantine, who had total confidence in himself, needed a larger arena in which to display himself in front of his subjects. The best such setting a large Roman city could provide was its hippodrome, the circuit for chariot racing. The most impressive of these, and the one which provided a model for others in the empire, was the Circus Maximus in Rome, which ran along the southern edge of the Palatine Hill. The site is completely deserted today, just an open space in the shape of an oval, and it is hard to recreate any sense of what it was like in its heyday; but by the time it was finally completed, around AD 105 in the reign of the emperor Trajan, it was over 600 metres long and 140 metres wide with a capacity of 150,000 spectators – three times the number who could fit into the nearby Colosseum.

When the emperor was in residence in the imperial palace on the Palatine Hill he would preside over the races from an imperial box set in the side of the hill, and even if not there himself he would use the games as a means of sustaining his popularity. His chief responsibility lay in providing the horses. In a typical day’s racing there would be twenty-four races and, with four horses to each of twelve chariots (four teams of three), each race would need forty-eight horses, over 1,150 in total. The demand for horses was so heavy, in fact, that whole herds of wild horses were set aside to help the emperors to meet it. Yet there was much more than this to the chariot-racing spectaculars. Along with the games in the great amphitheatre of the Colosseum,* they constituted the only occasion when an emperor could see and be seen by his subjects en masse – and they were not going to miss the opportunity to let him know their feelings. ‘The Romans gather enthusiastically in the circus,’ wrote the historian Josephus in the first century AD, ‘and there the assembled throngs make requests of the emperors according to their own pleasure. Emperors who rule that such petitions are to be granted automatically are highly popular.’ Josephus goes on to describe the response of the emperor Caligula (emperor AD 37–41), who sent his men among the crowds to arrest, and put to death, anyone who shouted for favours. Not surprisingly Caligula was himself murdered a few weeks later (although his behaviour in the Circus was only one of his crimes against the people that drove the conspirators to assassination). If emperors did not grant a request they were at least asked to produce a reason for the refusal. On one occasion the crowd demanded of the emperor Hadrian (r. AD 117–38) that a victorious charioteer who happened to be a slave be given his freedom. Hadrian refused with the modest explanation that he had no power to give away the property of another. Any refusal had to be given directly by the emperor himself; the crowd considered it insulting if a message was relayed to them by a herald.

The more confident emperors knew how to use the opportunity offered by a clearly defined area, the imperial box, which was set off from the crowds and above them, giving everyone a clear view of the emperor in his glory. Augustus, who had a highly sophisticated approach to crowd management, once countered a protest against new laws encouraging the equestrian class to marry by appearing in the box overlooking the Circus Maximus with a collection of children assembled from his extended family to make the point that marriage had its purposes. Constantine showed the same confidence in his use of the hippodrome. Wherever he made his capital he enlarged the existing hippodrome or built a new one, and in every case it ran alongside his palace with the imperial box as a display area between the two. In 310, at the beginning of his career, when he was in control only of northern Europe and based at the provincial imperial capital of Trier, he had built a hippodrome next to his palace. When he arrived in Rome in 312, after his great victory at the Milvian Bridge, he found that Maxentius, whom he had defeated, had constructed a massive hippodrome to the south of the city (whose ruins can still be seen). Constantine retaliated by showering patronage on the Circus Maximus. It is reported that it was ‘wonderfully decorated’ by him, with a new portico and golden columns and statuary. An extended seating area from this date has been uncovered in excavations. Between 317 and 323 Constantine was campaigning in the Balkans and based at Sirmium, another provincial capital, and here again he seems to have completed a hippodrome.

The new hippodrome in Constantinople, then, was bound to be something special. It was modelled on the Circus Maximus in Rome to make the point that this was a ‘new Rome’, and Constantine decorated the barrier (the spina) which ran between the turning posts with a mass of statues. The hippodrome was about two-thirds the size of the Circus Maximus, but this was in a city which had, as yet, only a fraction of Rome’s population. The fourth-century Christian scholar Jerome tells of whole cities being stripped of their treasures to decorate it and the other open spaces in the city. Among the treasures known to have been taken by Constantine for this purpose were the column commemorating the Greek victory over the Persians in 479 BC, from the oracle site of Delphi (the base still remains today, where it was embedded in the spina), and statues of Apollo (one of which may also have been taken from Delphi) and of the Muses (from Mount Helicon in Boeotia). From Actium, in north-western Greece, came another victory monument, that set up by Augustus to commemorate his defeat of Mark Antony there in 31 BC. One motive for building Constantinople was to celebrate Constantine’s victory over a rival, Licinius, who had ruled the eastern part of the empire, so bringing in an earlier victory monument put up by a westerner to show off his own defeat of a rival was highly appropriate.

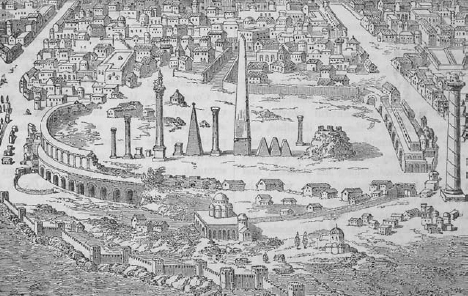

The remains of the Hippodrome in Constantinople c.1600. Note the obelisk, an Egyptian symbol of the sun, which was a common feature of hippodrome decoration. The obelisk and the other monuments were placed along the spina, the barrier around which the chariots raced. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

To add to the aura of the hippodrome a massive statue of Hercules was transported all the way from the Capitoline Hill in Rome. Hercules was often associated with chariot racing because he was believed to have shown the same combination of physical strength and cunning in achieving his labours as was needed by a charioteer. At the Circus Maximus a statue of Hercules Invictus, Hercules the Unconquered, stood near the starting gates, and this part of the Circus was believed to be under his special protection. The Hercules brought to Constantinople was of great aesthetic and symbolic importance as it was said to have been made by Alexander the Great’s favourite sculptor, Lysippus. The Romans had looted it from the Greek city of Tarentum in southern Italy in 209 BC and transferred it to the Capitoline Hill in Rome as a reminder of their humiliation of the city.

If one is trying to distinguish a hippodrome from the other monuments one finds depicted on a Roman coin, one clue to look for is an obelisk, a needle-shaped stone monument. Obelisks originated in ancient Egypt as a symbol of the sun, and they were derived from a stone called the benben that was placed in the main temple to the Egyptian sun cult at Heliopolis at the southern end of the Nile delta. Augustus, who had conquered Egypt for the Roman empire, brought back an obelisk from Heliopolis and in 10 BC he had it placed on the barrier in the Circus Maximus, adding to it his own dedicatory inscription to the sun.* In doing this he was honouring ancient traditions which linked the sun to chariot racing. The story goes that the word circus itself was derived from the name of Circe, the daughter of Helios the sun-god (Sol to the Romans), who had established the first chariot races in his honour. In the Circus Maximus there was an ancient temple to Sol near the finishing line.

The obelisk features prominently in a much later account by a court official, one Corippus, which describes the rituals surrounding the accession of a Byzantine emperor, Justin II, in AD 565 in Constantinople. These included a presentation of the new emperor to the people in the hippodrome. Corippus breaks off his narrative to explain why the circus and the sun were so closely linked.

The Senate of old [in Rome] sanctioned the spectacles of the new circus in honour of the New Year’s sun and they believed that by some ordering of the world there were four horses of the sun, which were symbols of the four seasons in the recurring years. Thus the senators of old laid down that there should be in the likeness of the seasons as many charioteers and as many colours [the four teams in any Roman chariot race were known by their colours, Blue, Green, Red and White] and they created two opposing parties, just as the coldness of winter strives against the warmth of summer.

Corippus goes on to explain that a circus itself is designed to represent a whole year divided into seasons. The four equinoxes are represented by the turning posts at either end, the centrally placed obelisk and the ‘eggs’, a set of egg-shaped marbles which stood close together in a frame halfway along the barrier and were removed one by one as each lap was covered.* In other words, there were four distinct and equal stretches of the circuit, two either side of the spina. Corippus’ account has found support in the rare survival of a glass bowl, dating from the middle of the fourth century and probably made in Cologne, where it was found in 1910. It has a central medallion with a bust of Sol in it around which four chariots parade. They are divided from each other by emblems of the circus: an obelisk, a set of ‘eggs’ and the two turning posts.

After Augustus it became the custom for every circus to have its own obelisk, although in Constantinople the earliest one of which we have direct evidence was placed there by the emperor Theodosius I in AD 390 in celebration of peace treaties with the empire’s enemies, the Goths and the Persians. A second was set up early in the following century. Yet even if we know of no obelisk placed in the hippodrome by Constantine, his own close association with the sun was embedded in ceremonies in the hippodrome, as could be seen in the official inauguration of the city in May 330. The day’s events began in the presence of the emperor with the lifting of a great gold statue of him, which had been fashioned from an ancient statue of the sun-god, on to a column (which still stands, in a much battered form, today). Dressed in magnificent robes and wearing a diadem encrusted in jewels, Constantine himself then processed to the imperial box which overlooked the hippodrome. Among the events which followed one stood out: the arrival of a golden chariot carrying a gilded statue of the emperor, again shown as a sun-god, which in turn held a smaller figure of Tyche, the goddess of good fortune. For the next two hundred years the ritual drawing of the statue and chariot through the hippodrome was to be re-enacted on the anniversary of the dedication.

This engraving of 1806 shows a Roman mosaic of a chariot race discovered at Lyon in France. Note the starting gates on the left and, inside the spina, the obelisk and the rows of ‘eggs’, one of which was removed after each lap. (Musée de la Civilisation Gallo-Romaine, Lyon, France/Bridgeman Art Library)

Between anniversaries Constantine’s chariot and its statue were placed at the Milion, a grand imperial building in the shape of a gilded canopy with four arches, which stood outside the hippodrome, but close to its starting gates, where the ceremonial processional route into the city, the Mese, ended. Beside it stood a team of four horses.

Memories of Constantine’s inauguration lingered long in the city. In an eighth-century chronicle of Constantinople’s monuments, the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai (literally, ‘Brief Historical Notes’), we read that

At the golden Milion a chariot of Zeus Helios [Zeus in the guise of the sun-god] with four fiery horses driven headlong beside two statues has existed since ancient times … And the chariot of Helios was brought down into the Hippodrome, and a new little statue of the Tyche of the city was escorted in the procession carried by Helios. Escorted by many officials, it came to the Stama [the place where the victorious charioteers received their palms of victory] and received prizes from the emperor Constantine, and being crowned it went out and was placed in the Senate until the next birthday of the city.

In the same chronicle the writers, who are assumed to be court officials, describe ‘a statue of a woman and an altar with a small calf’ in the hippodrome itself. ‘With these too were four horses shining with gold and a chariot with a charioteer [possibly Tyche?] holding in her right hand a small figure, a running image.’ Victory was often personified as a running woman, but this statuette could also have been of an athlete; female charioteers were rare. ‘Some say’, they go on, ‘that the group was erected by Constantine while others say merely the group of horses, while the rest is antique and not made by Constantine.’ This statue too appears to have been hauled in its chariot in procession through the hippodrome by the citizens of Constantinople, who, the chronicle records, were dressed in white mantles and carried candles, on each anniversary of the city’s foundation. One assumes that ‘the four horses shining with gold’ remained at their base to be rejoined by the chariots when the ceremony was over.

Later, a century after Constantine, another team of four horses was set up as a permanent feature in the hippodrome, over the starting gates where, according to one observer, they still stood in the twelfth century. These horses were said to have been brought by the emperor Theodosius II from the Greek island of Chios, close to the coast of Asia Minor, in the early fifth century. Chios was a prosperous place, its inhabitants – according to the historian Thucydides, writing in the fifth century BC – among the most wealthy of all the Greeks. Its trading networks stretched from the Black Sea to Egypt and as far east as southern Russia, while at home its population was sustained by a fertile plain on the east coast. Unlike much of mainland Greece, Chios would certainly have had the pasture and wealth to support horses, and it is possible that the hippodrome horses, if they came from there, were commissioned by a victor in the Greek games (which will be described in the next chapter).

So we know of at least three teams of four horses in Constantinople in the century after its foundation. Of the two whose chariots were paraded in the hippodrome, either or both could have been made by Constantine or brought by him from another site. There is also another possibility: that Constantine found one or more teams of horses already in place in Byzantium when he arrived to transform the city. The historian Dio Cassius (AD 164–after 229) recorded, for instance, that when the emperor Septimius Severus besieged Byzantium in the 190s ‘the stones of the theatres, the bronze horses and the bronze human figures’ were hurled at him as ammunition. It has been argued that Septimius Severus might have recreated the horses to atone for their sacrilegious destruction and that these would have been found by Constantine when he rebuilt the city. On the other hand, Septimius Severus, whose regime depended on continuous celebration of military triumph, may well have commissioned a triumphal quadriga on his own account to celebrate his taking of Byzantium when he rebuilt the shattered city. If Constantine had found a quadriga in the city he may well have chosen to preserve it as a fitting symbol of his own success.

Whatever their origins, it is likely that one of the three teams mentioned in the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai is the set of gilded horses described by Bernardo Giustiniani in Venice in the passage quoted on p. xv and said by him to have originally belonged to ‘the chariot of the sun’ and to have been ‘brought from Constantinople’. But before we explore further, we need to understand why horses came in teams of four.