IF ONE MOVES WESTWARDS BY SEA FROM CONSTANTINOPLE, out through the Hellespont into the Aegean and then southwards to Greece, one hits landfall on the long coastline of the island of Euboea. The sensible sailor heads inland around Cape Artemisium on the north-eastern coast, so as to reach the sheltered waters between Euboea and the mainland. (A large part of the Persian invasion fleet of 480 BC was lost, driven onshore by a gale, when it tried to edge round the island on the outside.) There had long been trading links between Euboea and the civilizations of the east, but in 1100 BC at the onset of the so-called Dark Age these contacts had been disrupted by what appears to have been an economic collapse followed by widespread conflict. Until recently early Greek history was believed to be almost uneventful between that date and the revival of trade and confidence in the eighth century which marked the end of the Dark Age.

Then in 1981 a remarkable discovery was made at Lefkandi, a site between Chalcis and Eretria on the inner coast of Euboea. Archaeologists found a great hall, some 45 metres long and 10 metres wide, dating from 1000 BC. It was unlike anything known from earlier times. Its mud walls had been built on stone foundations, and around them was a colonnade of wooden posts. More remarkable still, there was a burial within the walls: of a man, who had been cremated, and a woman, along with an array of goods more extensive than anything that could be expected for the time. There were a spear and a sword in iron, an engraved bronze vessel and, with the woman, gilt hair coils and gold discs which had been laid on her breasts. All this suggested a couple of high status who had the power to organize a large and skilled labour force and who also had access to the goods of the east. But their community seems to have lost its vigour. The archaeological evidence suggests that part of the building at least collapsed soon after the burial, and it appears to have been another century before Lefkandi resumed contact with the east.

In a second compartment next to the main burial chamber there was another extraordinary find: the skeletons of four horses, two still with iron bits in their mouths, which had presumably been sacrificed before being buried alongside their owners. Horses are a rare find in southern Greece because there is so little pasture for them; one has to travel northwards to the plains of Thessaly to find land where horses can be grazed easily. In fact, in Homer’s Odyssey we read that Telemachus, the son of Odysseus, has to turn down the gift of three stallions from King Menelaus of Sparta because his home, Ithaca, has not enough pasture or ‘running room’ for them. So anyone who could afford to sacrifice no fewer than four horses at once must have been a figure of impressive wealth and social status, as the hall in which the burials were made suggests.

Teams of four horses appear in the earliest Greek literature. In his epic the Iliad, written down some 250 years after the hall in Lefkandi was built, in about 750 BC, Homer tells how Hector, champion of Troy, and Achilles, hero of the Greeks, both advance into battle in four-horse chariots. The vehicles are driven by charioteers, behind whom the heroes stand, ready to jump down into the fighting. Lesser heroes have only two horses to their chariots. What is particularly attractive about Homer’s account is that the horses mean something to their owners. Hector’s horses are even named – Golden and Whitefoot, Blaze and Silver Flash – and are said to receive special care from Hector’s wife Andromache, who feeds them honey-drenched wheat mixed with wine. These are horses treasured within the family, and they can respond to the affection. When Achilles’ charioteer is killed his set of horses ‘stood, holding the blazoned chariot stock still, their heads trailing along the ground, warm tears flowing down from their eyes to wet the earth … The horses mourned, longing now for their driver, their luxurious manes soiled, streaming down from the yokepads, down along the yoke’ (Robert Fagles’ translation).

We know that any ancient Greek or Roman chariot drawn by four horses always had the horses harnessed alongside one another, not in two sets of pairs as in a stagecoach. It is an unexpected arrangement because it is such an inefficient way of using the strength of the horses. It would have been impossible to have harnessed them all to the same yoke, because if this had broken the team would have collapsed in a dreadful tangle; so the outer two horses are always trace horses, running alongside the inner pair who do have a yoke between them. (The fact that only two of the horses in the Lefkandi burial had bits suggests that they were harnessed in the same way.) The trace horses add nothing to the pulling power of the team and they also make the chariot much more difficult to manoeuvre. A skilled charioteer can just about drive the four along on level ground but it would have been impossible in the dust and noise of an actual battle, and we know that in any real war only two-horse chariots were used.

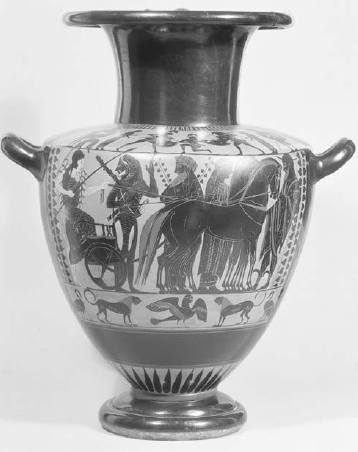

With two extra horses added on purely for display, the four-horse chariot was a clear sign of status in a land where horses were always rare, and this is why Homer uses it to pick out the two most distinguished heroes of his epic from the others. We know that Achilles and Hector must be truly great men if they have horses to spare. But we also find teams of four horses in many other contexts where the owners are heroes, aristocrats or gods. So in eighth-century BC Athens aristocratic women were buried with pottery containers decorated with four model horses on the lid and chariot wheels on the side. When gods and goddesses are shown in chariots on pottery, they invariably have four horses. There is a good example in the British Museum of a krater (a bowl for mixing water and wine) from Athens, dated to about 580 BC, which shows all the gods of Mount Olympus attending the wedding of Peleus and the nymph Thetis, soon to be the parents of Achilles. The gods stand in pairs on the chariots, each of which is drawn by four horses. On the east pediment of the Parthenon, which shows the rising of the sun-god Helios and the setting of the moon-goddess Selene, both were carved with four horses drawing their chariots. (One of the horses of Selene which survives is considered by many to be among the finest pieces of classical Greek sculpture and will reappear in our story later.) More remarkably, perhaps, in the famous frieze which ran along the upper cella walls of the Parthenon in Athens, the chariots which make up part of the great procession of citizens each have four horses. Here the Athenians are giving themselves the status of heroes by virtue of their belonging to the city they believed, with some reason, to be the greatest of the Greek world.

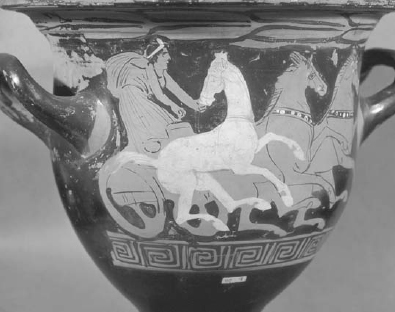

A quadriga shown on an Athenian krater (a bowl for mixing wine and water) dating from the sixth century BC. The standard representation of a quadriga showed the two inner horses facing towards each other, and the two outer facing away from each other. Note that the outer horses are trace horses and have no pulling power. (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford/Bridgeman Art Library)

The Lefkandi burial provides the earliest evidence that four-horse chariots were actually built in Greece, and the Iliad suggests that they were associated with aristocratic funerals. When Achilles’ beloved companion, Patroclus, is killed by Hector, Achilles holds funeral games in his honour, and ‘with wild zeal slung the bodies of four massive stallions on to the pyre’. Then there is a chariot race. It is a very simple affair – the chariots take off for about a mile, turn round a post and then make for home – and seems to have been contested by two-horse chariots; but only a few years after Homer was writing, in 680 BC according to tradition, four-horse chariot racing appears as an event in the Olympic Games and then in other Greek games. The sudden appearance of four-horse chariots in the games fits well with the decline of the old aristocratic world: battle between great heroes is no longer part of warfare, and it seems that the aristocrats transferred their combative energies into competitive games. Having four horses to each chariot made the point that these were no ordinary competitors but men of high birth, to whom victory in these races brought great acclaim. Unlike any other Olympic event, however, it was possible to compete by proxy, employing an outsider as charioteer, even though it was the owner of the chariot who enjoyed the kudos* of victory. The Athenian Cimon won the chariot race at three Olympic Games in a row, those of 532, 528 and 524 BC, and celebrated – in an echo of Lefkandi – by having his horses buried in his family tomb. In 416 BC another Athenian aristocrat, Alcibiades, entered no fewer than seven teams in the Olympics and then unscrupulously used his success to manipulate the city’s democratic assembly. ‘There was a time’, he told his credulous audience,

A mythical scene from an Athenian water jug of c.550 BC, with Athena (identifiable by her spear) driving a quadriga as is appropriate to her status as a goddess. (British Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library)

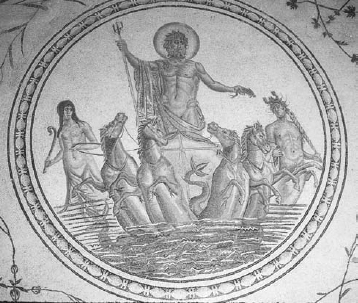

Neptune, the sea-god, rises from the sea in his quadriga. Roman mosaic, second to fourth century AD. (Ancient Art & Architecture Collection)

when the Greeks imagined that our city had been ruined by the war, but they came to consider it even greater than it really is because of the splendid show I made as its representative at the Olympic Games, when I entered seven chariots for the chariot race and took the first, second, and fourth places … It is customary for such things to bring honour, and the fact that they are done at all must give an impression of power.

This exceptionally fine bronze relief of a quadriga from the sixth century BC comes from the rim of the Vix krater found in the grave of a Celtic aristocrat in France. The hoplite (armed foot-soldier) preceding it suggests a battle scene. (Musée Archeologique, Chatillon sur Seine, France/Bridgeman Art Library)

There are examples of aristocrats driving their own chariots in the games (and being applauded for doing so) but it was rare. Driving a chariot around turning posts in a race with many others, perhaps as many as forty in Greek games, needed enormous skill. The inner of the trace horses had to be guided around the turning post (which was always passed to the left), taking the two yoked horses and the outside trace horse with it and so on, for twelve laps, ten thousand metres in total. Collisions and falls were common. One can see the challenges from the account of a race at the Olympic Games given by the playwright Sophocles in his play Electra. First, the start:

then, at the sound of the bronze trumpet, off they started, all shouting to their horses and urging them on with their reins. The clatter of the rattling chariots filled the whole arena, and the dust blew up as they sped along in a dense mass, each driver goading his team unmercifully in his efforts to draw clear of the rival axles and panting steeds, whose steaming breath and sweat drenched every bending back and flying wheel together.

Then, as must have happened frequently, things went catastrophically wrong.

At the turn of each lap, Orestes reined in his inner trace-horse and gave the outer its head, so skilfully that his hub just cleared the post by a hair’s breadth each time; and so the poor fellow had safely rounded each lap but one without mishap to himself or his chariot. But at the last he misjudged the turn, slackened his left rein before the horse was safely round the bend, and so struck the post. The hub was smashed across, and he was hurled over the rail entangled in the reins, and as he fell his horses ran wild across the course.

The race was made more hazardous by the custom of holding the event at dawn. As we have seen, the sun was linked to chariot racing, and it may have been in honour of the sun that the race was held at first light; but the timing made it even more hazardous, for there would have been places in the course when the chariots were racing straight towards the rising sun.

Driving four horses was challenging enough in itself, but the Greeks, and later the Romans, made things even more difficult by the way they harnessed their horses. The yoke of the two inner horses was attached to a collar which ran around the neck. This must have caused a great deal of discomfort to the horse, which was, in effect, closing its own windpipe as it pulled, and reduced its traction power considerably. (These collars remain in place on the St Mark’s horses, whose thick, muscular necks may have been copied from actual chariot horses.) The Greeks may have been ingenious in matters of the mind but were not always equally perceptive in matters of practical technology, and in this case at least the Romans were no better. When the heavy horse collar, which transfers the weight of the chariot or plough to the shoulders of the horse, was introduced into Europe in the tenth century AD it increased the pulling power of a plough horse by three or four times.

A charioteer driving his quadriga full speed. Late fifth-century Greek krater. (British Museum, London/Bridgeman Art Library)

The Romans learned the art of chariot racing through the Etruscans, who themselves learned it from the Greeks. The Etruscans, who were settled in the metal-bearing hills of the western coast of central Italy, had close trading relations with merchants from Euboea, who had established a trading base on the island of Ischia in the eighth century BC. These early Greek merchants and those with whom they did business on the Italian mainland were aristocrats, and the Etruscans absorbed all the trappings of Greek aristocratic living. In the cemeteries of the wealthier Etruscan cities, such as Tarquinia, painted tombs show Etruscans enjoying Greek-style banquets, listening to the music of flutes and competing in athletic and wrestling contests. The Etruscans were confident enough to adapt the Greek customs to their own; so, for instance, their wives were allowed to attend their banquets, something unheard of in Athens. They made their own adaptations of chariot racing, too. Their charioteers wore short tunics, in contrast to the Greek chiton, a robe which reached to the ground, and bound their reins around their bodies, again in contrast to the Greek custom of holding the reins freely in the hand. The use of the same practices by the Romans tells us that it was through the Etruscans that the Romans absorbed chariot racing. Legend is more specific: according to tradition, it was the Etruscan kings who ruled Rome in the sixth century BC who introduced chariot racing to the city and built the first circuit on the site of the later Circus Maximus.

A quadriga racing towards the meta, or turning post, at the end of the barrier. Roman terracotta plaque, probably first century AD. (British Museum, London)

The Greek games held at Olympia took place only every four years, so there was never a need to build a permanent stadium or even any sophisticated starting gates. The circuit was probably allowed to return to pasture between each event. The Romans had races much more frequently, several times a year and with many races on each day; so they took to building permanent hippodromes. The remains of many of these survive.

The more stuffy Roman aristocrats could scoff at the enthusiasm for the races. ‘It amazes me’, wrote Pliny the Younger, a senator and provincial governor, ‘that thousands and thousands of grown men should be like children, wanting to look at horses running and men standing on chariots again and again.’ Yet a race-day was an important social as well as sporting occasion. One of the most charming vignettes of such a day comes from the poet Ovid, who describes how he uses the cramped seats of the Circus Maximus to attempt to seduce the girl he has brought with him. The crowd is so tightly packed in that Ovid ‘has’ to defend her from the elbows of the spectator on her far side and the knees of the one behind her. Her dress trails in the dust, giving him the opportunity to lift it a little from the ground to reveal her legs. ‘What other treasures may not be hidden under that summer dress?’ he muses, and he eagerly sweeps away the dust which rises from the arena and settles on her. She fancies one of the charioteers, so in order to win her approval Ovid has to shout for him too. At the first start the favoured charioteer is pushed aside by his competitors, but the crowd appeal against an unfair start by flapping their togas and the race is restarted, this time leading to his victory. Now she is happy. ‘She smiled, eyes bright, inviting – That’ll do now. Keep the rest for – another place.’

The popularity of the games led to the hippodrome, with its marble seats, imperial box, richly adorned barrier and monumental starting gates, becoming one of the grandest buildings of a Roman city. In Roman games the four teams, Blue, Green, Red and White, each fielded up to three chariots per race and the starting gates were built as a row of twelve arches, each with a double lattice gate beneath it. Some races appear to have had only four chariots participating, others eight. The chariots lined up behind the lattice gates, their positions chosen by lot, and when the mappa, a ceremonial cloth, was dropped, ropes were pulled so that the latches of the gates sprung open simultaneously. The gates were built some 160 metres from the end of the barrier, which itself was set at a slight angle to the gates so as to create a wider space into which the chariots charged as they approached the barrier for the first time. They were required to keep in line at right-angles to the barrier round the first turning post, then back along the far side of the barrier until they passed a white line on the track, after which they could cut in front of each other. A Roman race was about half the length of a Greek one, perhaps because more were crammed into each day. Each consisted of seven circuits, some five thousand metres in total, with a finishing line probably halfway along the right-hand side of the final circuit.

This silver denarius from Rome of the first century BC (when Rome was still a republic) shows a charioteer carrying his palm of victory and receiving recognition from heaven. It was minted by a Roman magistrate, presumably as a symbol of victory. (The Art Archive)

Winning charioteers enjoyed enormous prestige. They drew up their chariots at the stama, a platform on the barrier, where they were awarded a palm leaf as a symbol of their victory, and then they completed a lap of honour. The crowd would pelt them with flowers and small change, and by the late empire they would be hailed with the cry of ‘tu vincas’, ‘May you conquer.’ It was a richly symbolic moment as this was the same cry that greeted an emperor whenever he appeared in public. The close link between the emperor and the chariot races was sustained by treating the charioteer as if he were a direct representative of the emperor.

And indeed, in some ways he was, because the four-horse chariot had already been developed in a different context altogether as a symbol of imperial triumph. The triumph was another ritual which the Romans adopted from the Etruscans. When an Etruscan commander won a victory he paraded through his native city in a four-horse chariot, and the Etruscan kings of early Rome appear to have done the same. By tradition they wore purple, which had always been a mark of high status, and a gold crown. When the Etruscan kings had been thrown out of Rome and a republic established (the traditional date for this is 509 BC) the ritual of the triumph remained, and was awarded by the Senate to a general for any major victory.

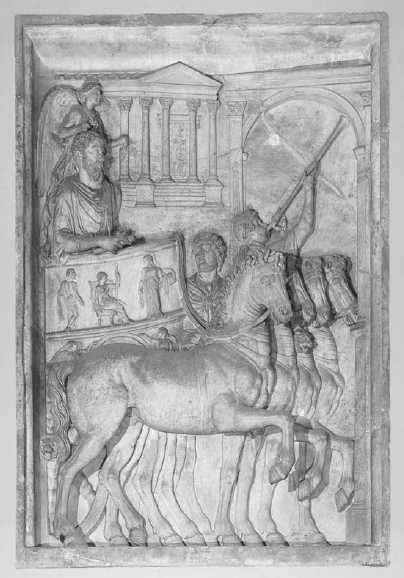

The triumphal chariot. This fine relief shows the emperor Marcus Aurelius celebrating a triumph in Rome in the late 170s AD. His son, the notorious Commodus, originally rode beside him, but his figure was erased after Commodus’ damnification. (Museo Capitolini, Rome/Scala)

The event was carefully stage-managed. The victor, dressed as if he were the god Jupiter (the Roman equivalent of Zeus) and crowned with a laurel wreath, would enter the city in his chariot, always with four horses (although one general, Pompey, showed off by substituting elephants for horses, with the embarrassing result that his chariot got stuck in the city gateway). Behind him would stretch a procession of his prominent captives and his booty – sometimes, after the sack of a great city, there would be enough of both to fill three days of such parades. The procession would progress through the Forum and then to the Capitoline Hill, where the victor would offer his wreath to the cult statue in the great temple to Jupiter as his captives were led off to be executed.

Yet the glory, though immense, was transitory. Even in the procession itself the victor would be accompanied by a slave, reminding him that he too one day would die, while his troops were allowed, for this occasion, to denigrate him. It was understood that a triumph never led to lasting political status but that the victor would retire from his command once the great day was over.

This was the ritual during the republic. The emperors, the first of whom was Augustus (r. 27 BC–AD 14), were careful not to be upstaged by their military commanders. After 19 BC only members of the imperial family could celebrate triumphs; and even then, when the emperor Tiberius allowed his charismatic nephew Germanicus a triumph after victories in Germany, the adulation shown by the crowds cruelly exposed the declining powers of the elderly ruler. One way round this was for the emperor himself to take responsibility for all victories achieved by his commanders. Thus the emperor Claudius – whose physical handicaps, the result probably of cerebral palsy, ruled out soldiering – awarded himself a truly magnificent triumph in Rome after part of Britain was conquered in AD 43.

The emperors also transformed the function of the triumph. Whereas in the republic it had to be a temporary moment of glory so that any further political ambitions by the victor were defused, the emperors both wished and were able to maintain themselves in a continuous state of glory, and the best way of doing this was to record their triumphs in some permanent form. So the triumphal arch was invented, and first used as a symbol of victory by Augustus. The advantage of the arch was that it could be built anywhere. Italy, Gaul and north Africa were the most common sites, although, of course, Rome was the most popular choice for an emperor. One could hardly do better than to have a great victory permanently commemorated in the Forum, the heart of the empire’s political and ceremonial life.

One of the earliest arches was that erected by Augustus in the Forum in 19 BC to celebrate the diplomatic coup by which the Parthians had been forced to surrender standards they had captured in an earlier defeat of the Romans. On the summit of the arch Augustus was shown as a conqueror in his chariot – which was, of course, drawn by four horses. The theme was continued within the magnificent new Forum which Augustus built in Rome alongside the original one. Its imposing temple, dedicated to Mars Ultor, Mars as a war-god who had achieved revenge (in reversing the earlier defeat by the Parthians), housed the returned standards and was also crowned by a quadriga. In the centre of the Forum was another quadriga carrying Augustus himself, and here he is portrayed as the culmination of the heroes of Rome, statues of whom stood in an adjoining ‘Hall of Fame’. To emphasize his status even more explicitly, works by the fourth-century BC artist Apelles, the most famous painter of antiquity, depicting Alexander the Great in his four-horse chariot, were displayed in the Forum. The message was clear: Augustus is the new Alexander, conqueror of the world.

A particularly famous triumphal arch of the first century AD was that erected by the emperor Nero in Rome in 62 to celebrate another victory over the Parthians, although on this occasion the fruits of an initial victory had been lost by incompetence and the signed peace represented a compromise. This did not deter Nero, who built his arch on the most sacred spot of all, one even more prestigious than the Forum: the Capitoline Hill which overlooked it. Its sides were covered by a mass of sculpture and statues, all focused on the theme of war and victory. On its top was, typically by now, a quadriga, and it was driven by Nero himself, flanked by personifications of Peace and Victory. (The representation is all the more absurd given the existence of an account by the historian Suetonius of Nero actually attempting to drive a chariot during games in Greece but falling out.) The arch was dismantled after Nero’s suicide and disgrace, but coins issued between 64 and 67 show it clearly, and some four hundred of these have survived. In the sixteenth century it was claimed by some Venetian scholars who had seen the coins that the horses from this quadriga, possibly transported to Constantinople from Rome by Constantine, were the ones then adorning St Mark’s.

This arch erected by Nero in Rome in the early 60s AD, and shown here on a sestertius, was believed by sixteenth-century scholars to show the original setting of the horses of St Mark’s. The placing of the horses’ front legs does not correspond with that of the horses in Venice and there is no significant evidence to sustain any link. (British Museum)