WITHIN A CENTURY OR SO OF THE EARLIEST RECORDED chariot race in Greek games, that of 680 BC at Olympia, chariot races were also being included in the other games which had been established in the Greek world. The most prestigious were those held on the Isthmus near Corinth, at Nemea in the Peloponnese and at Delphi (the Pythian Games). As we have seen, victory brought enormous kudos to the victor, who would often commemorate his success in some permanent form by dedicating a statue of himself or his chariot, usually in bronze, either at the site of the games themselves or in his home city. According to the Greek traveller Pausanias, writing in the second century AD, the earliest monument to horses bred in Greece was that erected by Cleosthenes of Epidamnus at Olympia in 512 BC. It represented Cleosthenes standing alongside his charioteer and his horses, whose names – Phoenix and Corax, Caecias and Samus – were inscribed on them. Virtually nothing remains of these commemorative works. It is one of the great tragedies of European history that virtually all the bronzes from antiquity have been lost, most of them melted down by sackers of sanctuaries, whether Christian iconoclasts who saw them as pagan idols or looters anxious to recycle the metal. (When he first saw the horses on St Mark’s, Goethe exclaimed: ‘What a magnificent set of horses. Praise God that Christian zeal did not melt them down to make candelabra and crucifixes.’) Those that have survived usually come from ancient shipwrecks, many of them off the coast of Italy, the ships presumably having foundered when on their way from Greece to Rome with cargoes to adorn the villa of a Roman emperor or connoisseur. Nero is known to have carted off five hundred statues from Delphi alone in anger when the oracle was unwise enough to condemn him for the murder of his mother. There was, however, one statue he missed in Delphi: a bronze charioteer which had been buried in a ditch in an earlier earthquake and never recovered in ancient times. It was eventually found by French excavators in the nineteenth century; but by then the chariot and its horses had long disappeared. They had probably been dug out after the earthquake and may even have been among Nero’s loot.

The Delphi charioteer was dedicated by a ruler from Syracuse, one of the Greek cities of Sicily, in about 470 BC. It is a superb piece of work. The charioteer stands in his long chiton, his reins in his hand and gazing forward, so serene in his moment of triumph that one can hardly imagine him caught up in the turmoil of the race he has just won. The serenity suggests that victory had brought him close to the gods, and the original placing of the quadriga within the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi reinforces the point. A cluster of reins, also in bronze, has survived with him. The body is slightly elongated, suggesting that it was to be placed high on a monument and viewed from below. The quality of the work can be seen in the feet, which have been cast with precision even though they would not have been seen by onlookers when the charioteer was in his chariot.

The casting of life-size figures in bronze was a comparatively new development in ancient Greece, but it was a technique which had been perfected remarkably quickly. Bronze, a mixture of copper and tin, had, of course, been known for centuries and it was the metal normally used for armour, which could be hammered into shape by skilled metalworkers to fit a particular body. At many Greek shrines, including Delphi, a mass of smaller solid bronze figurines, offerings to the gods, have survived. The problem with solid bronze figures is that the larger the figure the more likely it is that the bronze will crack when it cools. Life-size statues were also very heavy to move. It was important for the Greeks to learn how to cast hollow bronzes.

This superb bronze charioteer from a victory monument in Delphi dates from the fifth century BC. His serene gaze suggests that his victory has placed him close to the gods. (Scala)

The breakthrough came on the island of Samos in the Aegean. Samos was an important trading centre, with links to Egypt and the Near East. In the seventh century BC Samian traders began to import hollow cast bronzes from Egypt – and with them the technique used to make them, the lost-wax process. By the sixth century life-size figures were being cast. This is how the process worked. First the craftsman had to create a model of the planned figure (or each part of a larger figure) out of clay or sand or a sand-and-plaster mix. The model was then covered in a layer of wax sculpted in the shape of the intended work. Another clay covering was moulded over the wax and this was attached to the inner model by pins pushed through the wax into the core, so that the gap between core and outer covering would stay constant when the wax was melted out. A funnel was left in the outer mould along with vents for gases to escape. Then the wax was melted out and molten bronze poured in. Once the metal had cooled and solidified, the outer mould could be broken off and the inner figure either pulled out or broken up, leaving a hollow bronze. Typically, the thickness of these Greek bronzes was about 5 millimetres, although there are surviving examples as thin as 2 millimetres and as thick as 25 millimetres. What this meant was that large statues that were also relatively light could be made in one place and easily transported to another. Also, if it was possible to preserve the inner model, one could reuse it to create duplicate statues. Large statues would be made up of individual parts which were fitted together and the joins burnished over to make them invisible.

This red figure Greek drinking cup (fifth century BC) provides a superb illustration of bronze casting, especially the process of finishing off a cast statue. (Staatliche Museum/Bildarchiv Preubischer Kulturbesitz)

The lost-wax method of casting proved so successful that it has survived until modern times. In the Renaissance it was valued for this very reason, as a direct link back to classical antiquity, and it is from the sixteenth century that the most famous description of the process comes, in the autobiography of the Florentine sculptor and goldsmith, Benvenuto Cellini. Cellini, a brilliant but tempestuous craftsman, wanted to show that he was the equal as a sculptor of his great predecessors in Florence, Michelangelo and Donatello. Cosimo de’ Medici, the ruler of the city between 1537 and 1574, gave him his chance in 1545 by commissioning a life-size bronze of Perseus. This son of Zeus and Danaë, whom the god impregnated with a shower of gold dust, is remembered in mythology as the slayer of the Gorgon, Medusa, whose severed head he then turned against his enemies to transform them into stone. He was a fitting hero for Cosimo, who faced intense opposition from enemies both inside and outside Florence in the first two decades of his rule, and the finished bronze, with the head of Medusa flaunted at the onlooker, was to be on public show in the Piazza della Signoria in Florence as a symbol of his determination to survive. It was eventually unveiled in 1554 and still stands there today.

Technically the Perseus posed a daunting challenge, in that Cellini wished to cast in a single piece a large standing figure holding the head of Medusa at arm’s length. It was to be placed on the dismembered remains of Medusa, a figure Cellini modelled on the body of his mistress, Dorotea, and which was to be cast separately. The statue itself was to be 320 centimetres high – still a dwarf compared to Michelangelo’s great marble David, which was already installed in the Piazza, but for a single piece of cast bronze, enormous.

We know that Cellini visited his fellow Florentine Jacopo Sansovino in Venice, where the latter was city architect in these years, and it is inconceivable that he did not inspect the St Mark’s horses while he was there. (Sansovino cast a bronze door for the sacristy of St Mark’s in the 1540s.) Cellini had spent several years in Rome and would also have come to know the equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius which one of his patrons, Pope Paul III, had moved to the Capitoline Hill in 1538. He certainly had great models from the past to inspire him.

In his Life Cellini describes how he set about his task. First he created a framework of iron rods which was then covered with clay to make the core of the body; over this the wax was sculpted so as to highlight the finest details. The wax was carefully covered with a layer of clay about an inch thick, which was then bound in by a thicker mantle of clay strengthened by rings and wire. Every step of the process needed skill, not only in sculpting but in the placing of the channels through which the molten bronze would be poured into the cavity and the air vents through which gases would escape as the bronze cooled. An intuitive understanding of the cooling process was vital so that each part of the mould would be filled before the bronze had solidified, otherwise there would be gaping holes in the finished figure.

At last the melting of the wax could begin. It was done slowly over two days in a furnace fired by seasoned pine; one of the side-effects of this slow firing was to carbonise the clay core, which became porous and provided another means by which gases could escape. This was very important, for any bubbles left in the bronze would disfigure it.

By December 1549 Cellini was ready for the final stage, the pouring of the molten bronze into the mould. First a pit had to be dug under the brick furnace and the clay figure placed upright inside it. Here it was settled in place with earth around it, the vents preserved by running terracotta pipes from them into the open air. The mould had to be under the furnace so that the metal could run into it when it was at its most liquid – and in any case, it would have been too hazardous to carry the molten metal any distance. Then quantities of copper and already smelted bronze were gathered to be placed in the furnace, broken up into smaller pieces so that they would melt down more easily.

By now the tensions of the enterprise were taking their toll on the sculptor. Cosimo was proving a difficult and fussy patron, any request for more help was delayed by his court bureaucrats and, to make matters worse, Cellini’s brother-in-law died and he found himself suddenly responsible for his sister and her six children. All this when his reputation and self-esteem depended so heavily on success in this one great project. Racked with tension, as the heating of the metal began he was struck down by a severe fever and even believed himself to be dying. It is probable that Cellini dramatizes what happened next, but it is a good story. One of his workmen rushed into the room where he lay sweating, to tell him in despair that the work was ruined. As Cellini struggled to the furnace, cursing and kicking his workmen, he found that the fire was simply not hot enough: the bronze lay in a congealed mass which would never have flowed into the recesses of the mould. (There is a kind of chestnut cake, castagnaccio, still made in Italy, which remains sticky after baking, and Cellini compared his bronze to this.) He desperately called for oak to be thrown on the fire to raise the temperature, and it worked – but the furnace now became so hot that its top exploded and bronze began to trickle out. Even now it was not liquid enough, and in his frenzied and fevered state Cellini began wondering whether someone had interfered with the alloy. (He may have been right. The more tin is added to the copper, the lower the melting point – it takes 13 per cent tin to lower the melting point by 100 degrees Celsius, and 10 per cent is a usual mix. Recent tests on the Perseus have shown that Cellini’s original mix contained only 3 per cent tin.) The only solution was to add more tin. There was no time to lose, and in desperation Cellini called for all his household pewter, 200 pounds of it, in platters and bowls, to be thrown on the furnace. At last the metal began to flow easily and he was able to guide it into the mould, which gradually filled to the brim. Then there were two anxious days of waiting while the metal cooled before the statue could be exposed; but Cellini’s judgement had been exact. The bronze had not only filled the cavities of Perseus’ and Medusa’s heads perfectly, it had flowed so successfully downwards that only at the very bottom of the statue, at the toes of the right foot, had the bronze not filled the mould. These missing details could be crafted on separately.

It might be thought that with this triumph Cellini’s work was virtually complete. Yet it took him a further three or four years of labour on the bronze to perfect it for display. Each hole left by the pins which held the mould together had to be filled in and burnished over; minor blemishes left by gases had to be erased and some details of the statue slightly recast. Wings were added to Perseus’ head and a realistic ‘flow of blood’ from Medusa’s. An iron sword was fixed to Perseus’ hand. Then the whole was given a protective patina, made up of a mixture of alkaline sulphides, which darkened it, in this case so successfully that the statue has never been penetrated by rain or damaged by corrosion, even though it has stood for four and a half centuries in the open air.

Cellini says virtually nothing about these years of painstaking work, and it is only a recent restoration of the statue which has revealed what was involved. The Perseus is quite exceptional in its size and detail; even so, the whole episode shows just how skilled the casters of such statues had to be. A whole range of skills and processes had to be mastered and performed, often in quick succession, without mishap. It was as important to understand, albeit perhaps intuitively, the science of metallurgy as it was to be able to conceive and sculpt such a masterpiece.

Cellini’s famous statue of Perseus, which still stands in Florence. Its casting, as recounted by Cellini, provides one of the most vivid accounts of the dramas and difficulties involved in the process. (Loggia dei Lanzi, Firenze/Scala)

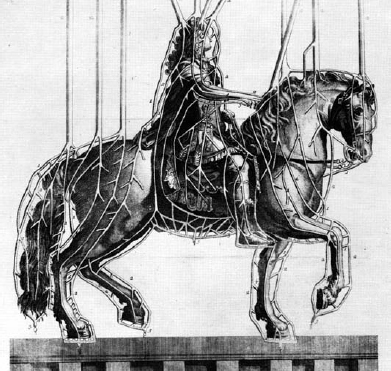

There is a variation of the lost-wax method that Cellini also describes in his writings, used when a bronze original was to be copied or when a particularly large bronze was to be cast. This is known as the indirect method. An original figure, say an existing bronze of a man on horseback, was taken and a series of rows of soft plaster blocks piled up around it, each one moulded around the part of the original figure that it touched. When the blocks were dismantled, each one bore a concave impression of part of the horse and rider. The inside of each plaster block was coated in wax which was then prised off the plaster when cold. The wax sections were then assembled carefully from the bottom up around a core made of clay or plaster which resembled the shape of the existing sculpture. Eventually one would have a complete wax model assembled around a core; and if the shape of the wax had been kept undistorted, this model would correspond to the original figure. Next the wax would be coated with a clay mixture (in an eighteenth-century example of a large equestrian statue of Louis XIV, this is recorded as earth mixed with dung and broken white pottery). As in the original method, this outer mould would have to be fixed to the inner core with pins or nails which ran through the wax. A wall would be built around the construction and the gap between the outer mould and the wall filled in with broken earthenware. The whole would be heated for a period – in the eighteenth-century example, fifteen days – during which the outer mould would harden and the wax flow out. This left an outer mould, the inner wall of which bore an exact concave copy of the original statue, and a core, pinned together so that the gap between the two was maintained. The worry was that when molten metal was poured into the cavities left by the wax the outer mould would crack and everything would be lost; so the mould would first be buried below ground level in a mixture of earth and stones. Now secure, the mould could receive the bronze poured in from above. Finally, the outer mould would be broken and the plaster core chiselled out, and one would have a bronze figure which was a close copy of the original.

It is usually possible to tell when this variant of the method has been used because the process leaves its mark on the bronze. When the wax is poured into the plaster it is then smoothed into every cavity with strips of wood. These leave their mark on the wax, which also varies in thickness. These variations are often reproduced on the plaster core and then reappear on the inside of the completed bronze. The indirect method was in use in Greece as early as the fifth century BC – the Riace warriors of c.460 BC, two male nudes possibly originally from an Athenian victory monument at Delphi, were cast in this way. So, too, were the horses of St Mark’s – a discovery which raises the possibility that they are direct copies of earlier statues; but, as we shall see in later chapters, there are far more remarkable features of their casting than this alone.

Metal sculptures pose a particular problem for archaeologists in that metal is not in itself datable. The dates at which particular processes are known to have begun or to have fallen into disuse provide only broad guidelines. We know that the Greeks of Samos learned of the lost-wax process in the seventh century BC, though there is no large Greek bronze statue which survives from before the late sixth century (an Apollo, dated to 525, which was buried for safety in the Piraeus, the harbour of Athens, before the Persian sack of the city in 480 BC); thereafter the method continued to be used for centuries, both in ancient Greece and then under the Romans after their conquest of the eastern Mediterranean. Both Greeks and Romans cast quadrigae, albeit for different contexts – the Greeks as commemorative monuments to victors in the games, the Romans as symbols of imperial triumph. The impossibility of any direct dating of the metal in which they were cast has meant that the St Mark’s horses have been attributed to some of the great sculptors of the ancient world – Phidias of the Parthenon, working in the late fifth century BC, and Lysippus, the favourite of Alexander, working in the late fourth century – as well as to specific emperors such as Nero (first century AD) and Constantine (fourth century AD). Altogether, as a result of the lack of other evidence, the horses have, as we noted earlier, been provided with dates for their casting which have spanned nine hundred years.

For the moment we must leave the mystery of the horses’ origin unresolved as we turn to their first known setting, in or near the hippodrome of Constantinople.

These plates, from a study of bronze casting published in France in 1743, show where the conduits for the casting of a large equestrian statue were placed (here for a statue of Louis XIV) and the process by which the wax model was bound and then heated from below to allow the wax to run out so that the bronze could be poured in to replace it. The horses of St Mark’s must have been cast by a similar process. (Above: Procuratoria di San Marco: Archivio Fotografico. Opposite: The Art Archive)