This race did not seek refuge in these islands for fun, nor were those who joined later moved by chance; necessity taught them to find safety in the most unfavourable location. Later, however, this turned out to their greatest advantage and made them wise at a time when the whole northern world still lay in darkness; their increasing population and wealth were a logical consequence. Houses were crowded closer and closer together, sand and swamp transformed into solid pavement … The place of street and square and promenade was taken by water. In consequence, the Venetian was bound to develop into a new kind of creature, and that is why, too, Venice can only be compared to itself.

J. W. GOETHE, Italian Journey (1786–8)

THE CITIZENS OF VENICE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN INDEPENDENT in spirit, their self-reliance and industry encouraged by the birth of the city as a refuge for mainlanders. The first permanent inhabitants of the scatter of islands were probably driven there by the Lombard invasions of northern Italy in the sixth century, although the Venetians themselves preferred more romantic stories of origin. Stung by taunts that theirs was not a classical foundation, they put about a tale that the Rialto – the rivo alto or ‘the high bank’, later the commercial centre of the city – had been settled by refugees from the fall of Troy (traditionally dated, if it took place at all, to about 1250 BC), thus giving the city a heritage even older than that of Rome! Another legend told of the early Venetians fleeing Gothic invaders and setting up their city on 25 March AD 421, precisely at midday – 25 March was the feast day of the Annunciation, and so this legend explains the role of the Virgin Mary as a special protectress of the city. Those who wished to highlight the Christian origins of Venice developed a story concerning the ancient Christian city of Aquileia, on the Adriatic coast east of Venice, where, by tradition, the evangelist Mark had preached. It was said that when the city had been sacked by the pagan Attila the Hun in 452, Christianity had been preserved by certain of its pious inhabitants who had taken their faith with them to the Venetian lagoon. A medieval legend strengthened the link between the city and Mark by telling how the evangelist had spent a night on an island in the lagoon and had been told in a dream that his body would finally rest there. All these stories jostled in the Venetian consciousness, one myth gaining prominence when the city wished to highlight its antiquity, another when it wanted to show off its Christian credentials. The Venetians had a flair – shared, perhaps, with Constantine – for manipulating the symbols of the past to their advantage.

Venice had in fact been from its earliest years part of the Byzantine empire. Constantine had successfully preserved the Roman empire as a vast single political unit in the early fourth century, but thereafter it began to crumble under the weight of barbarian invaders. In the fifth century the western empire finally disintegrated – but parts of Italy and north Africa were reconquered in the sixth century by Justinian. Among the territories newly subject to him was north-eastern Italy, the Veneto, its people loosely controlled by the exarch of Ravenna further south on the Italian coast. In the eighth century, the inhabitants of the growing settlement of Venice acquired their own resident official, who was given the customary name of a local governor: dux. This is how the office of doge, the name given to the chief magistrate of Venice, originated, although contrary to what the Venetians themselves liked to believe, the first doges were not Venetians but Byzantine officials.

In the ninth century, a time of turmoil in Italy, the Byzantine empire negotiated a semi-independent role for Venice: it remained part of the empire, but paid tribute to the neighbouring Frankish kingdom of Italy in return for a guarantee of its ‘borders’ and freedom to trade. One of the turning points in the city’s history was the seizing of the supposed body of St Mark the Evangelist from Alexandria by Venetian sailors in 828. (They concealed the body in a drum of pork to deter inspection by Muslims.) The first patron saint of the city had been the Byzantine Theodore; now he was discarded in favour of Mark, whom, as we have seen, legend linked to nearby Aquileia.

It was the freedom to trade that underlay the survival and growing prosperity of the city. Although the Adriatic coast itself can be treacherous, Venice itself was well protected and proved an ideal staging post between the eastern Mediterranean and northern Europe. Its merchants could exploit trade routes across the Alps which had been in use for centuries. The special status of Venice within the Byzantine empire was recognized by a treaty of 992 in which Venetian ships were given privileges at Constantinople in return for Venice’s promise that it would remain a loyal servant of the empire. It had few obligations in return, and in any case was much too distant from Constantinople for any effective control to be exercised by an empire which was itself constantly under threat from hostile neighbours closer to home.

By the time of this agreement the tentacles of Venetian trade stretched through the eastern Mediterranean and even into the Islamic world, which had devoured much of the Byzantine empire in the seventh and eighth centuries. Motifs from Arabic architecture can be found in Venice alongside Greek influences from Byzantium – all woven into styles and themes which were distinctively Venetian. So begins the almost fairy-tale magic of Venetian architecture, the spell enhanced by the contrast of light and shade and glitter of the water. ‘While the burghers and barons of the north were building their dark streets and grisly castles of oak and sandstone,’ wrote John Ruskin in his Stones of Venice (1851–3), ‘the merchants of Venice were covering their palaces with porphyry and gold.’

The first inhabitants of Venice had shifted the nucleus of their city from island to island as conditions dictated. (The isolated and atmospheric ‘cathedral’ on the island of Torcello, an island from which the Venetians were driven by malaria, remains as a reminder of their changing fortunes.) Eventually a piece of firm land in the central lagoon, well placed on the edge of a deep basin, the Bacino, was selected as a foundation for the first doge’s palace, which in these early, unsettled days was built as a fortress. Behind it was a small church, in effect the doge’s private chapel, which had originally been dedicated to Theodore. It was here that the relics of St Mark were laid to rest in the ninth century; the church was rededicated in his name, and the area became the ceremonial centre of the city. In the eleventh century St Mark’s itself was rebuilt in its present form, in the shape of a Greek Orthodox church – almost certainly modelled on the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, the burial place of Constantine, with its five mosaic-adorned domes. Around it and what had by now become the palace rather than the fortress of the doges, new public areas were set out. As entry to the city was from the Bacino, a proper landing ground with a pavement, the Molo, was built along the seafront. This new space, the Piazzetta, was soon dominated, as it still is, by two huge granite columns from Alexandria, set up there in the twelfth century, on top of which were later placed statues of St Theodore with his crocodile and a winged lion, the emblem of St Mark. The visitor would look down between them to the corner of St Mark’s, where an official entrance through the narthex led into the church.

The Piazzetta was always a political space. The Grand Council of Venice would meet in the Doge’s Palace and spill out into the open air for less formal discussion; foreign dignataries would be greeted on the quayside. However, again in the twelfth century, another great open space was being laid out to the west of St Mark’s. Impediments such as the chapel of San Gemignano and an orchard belonging to a nunnery were cleared away – though the chapel was rebuilt further to the west after the pope protested at its wanton destruction – and a rectangle some two hundred metres long was marked out. This was to become the Piazza San Marco – St Mark’s Square.

A direct source of inspiration for this new feature may have been the courtyards of the mosques of the Islamic world; certainly that of Damascus was well known to Venetian traders and very similar in size to St Mark’s. Another may have been the imperial forums of Constantinople, twelve of which still stood in the twelfth century. The Venetian traders knew Constantinople well – as we have seen, they had their own resident community there – and from the tenth century it was the custom for the doges’ sons to be educated in the imperial capital. A hinge between Piazza and Piazzetta was formed by the Campanile, the famous bell tower, originally set up in the ninth century, and visible far out to sea. The bells would ring daily to mark the start and end of the craftsmen’s day and the offices of the church, as well as less regularly to summon the nobles to vote in council and to announce public executions.

Whatever the contemporary inspiration for the ceremonial areas of Venice, the Venetians adopted many of the features of the forums of the ancient world. Venice’s rivals on the mainland, such as Padua and Verona, could boast their descent from Roman cities; Venice could not, but it could create an artificial heritage by constructing a dignified square and embellishing it with imported antiquities. These were not difficult to find, as many of the great classical cities of the east had fallen into ruin as a result of earthquakes, Arab invasions and abandonment. As early as the ninth century ancient columns were being brought back to Venice, and in the eleventh century an order went out to look for marble for the rebuilding of St Mark’s. One fourteenth-century decree ordered a captain to search out medium-sized columns and shafts of any variety of marble so long as these were ‘beautiful’ and could be brought back as ballast without overloading his galley. Of the six hundred marble columns in St Mark’s today, half are from outside Venice and all but fifteen of these from outside Italy. The effect, in the entrance to the west door, of the patterns of so many varied marbles is stunning; as the sun moved across them, enthused John Ruskin in the nineteenth century, it was as if the colours of the artists Rembrandt and Veronese had been united.

The other centre of medieval Venice was the Rialto, mentioned for the first time as a commercial centre in 1097. As in many other European cities of the time – London, with its distinct City and Westminster areas, is a good example – the ceremonial part of the city was kept well separate from its commercial area, and it was only gradually that the space between them was filled in and built on. The Grand Canal was preserved as the city’s main artery, echoing the rivers that ran through most European cities: the Seine through Paris, the Thames through London. It was, like them, crossed originally by only one bridge, at the Rialto, where the canal bordered the commercial area on its western bank. Lesser canals were the main means of transport in the city and Venice never needed to develop wide streets. Tourists still struggle today in their masses along the narrow Merceria, the medieval thoroughfare between St Mark’s and the Rialto which was first paved in 1272.

Any Christian inhibitions Venetians might have shared with their Byzantine overlords about indulging in trade were soon dissolved. In the twelfth century the standard rate on a loan in Venice was 20 per cent, which was justified as ‘an old Venetian custom’. Even when the church tightened up the laws on usury, the Venetians developed forms of contract which ensured that borrowing money cost the borrower money – and just to make sure that there was no divine disapproval, God himself was accorded the responsibility for the city’s success.

Since by the Grace of God our city has grown and increased by the labours of merchants creating traffic and profits for us in diverse parts of the world by land and sea and this is our life and that of our sons, because we cannot live otherwise and know how to survive except by trade, therefore we must be vigilant in all our thoughts and endeavours, as our predecessors were, to make provision in every way lest so much wealth and treasure should disappear.

Thus a fourteenth-century decree from the Senate. However magnificent the ceremonial centres of the city, it was never forgotten that it was the commercial areas at the Rialto, ‘that sacred precinct’ as one document of 1497 put it, which sustained their grandeur. Those who wanted scriptural support for Venice’s success could turn to chapter 28 of the prophet Ezekiel, where God talks of ‘that city standing at the edge of the sea, doing business with the nations in innumerable islands … your frontiers stretched out far to sea, those who built you made you perfect in beauty … Then you were rich and glorious surrounded by the seas.’ The fact that these apparently celebratory words come in the middle of a lamentation on the fall of Tyre, which had indeed been a great trading city like Venice, was no doubt passed over.

By the twelfth century, then, Venice was a vibrant and expanding city-state, although still technically subordinate to Constantinople. The relationship between the old empire and the increasingly self-confident city was bound to be uneasy, and in the late twelfth century it broke down completely. In 1167 a crushing victory by the emperor Manuel over the Hungarians allowed the Byzantines to expand down to the Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic. The Venetians, always obsessive about their control of the Adriatic, feared that this imperial advance might threaten their cherished freedom to trade without interference; so they began negotiations with the Hungarians to help them regain their lost territories. Doge Vitale Michiel then made the highly provocative move of placing a ban on trade with Constantinople. From this point things went quickly downhill. In retaliation for the ban, Manuel granted trading concessions to Venice’s great trading rivals, the Italian cities of Pisa and Genoa (It was now that the Genoans were given their own quarter of the imperial capital.) The outraged Venetian community in Constantinople rioted and then refused to pay for the damage. On 12 March 1171 Manuel ordered the arrest of all Venetians in Constantinople and the seizure of all Venetian shipping in the empire. The doge reacted by launching a Venetian fleet to do what damage it could do in the empire, and the cities along the Dalmatian coast were bullied back into Venetian control.

All this was self-defeating. Both cities stood to lose heavily from a breakdown in trade, and in the midst of all the tension and turmoil the Venetians sent envoys to Constantinople to negotiate. One of them was a worldly-wise and manipulative diplomat by the name of Enrico Dandolo. He was given no chance to use his skills, for by the time he arrived in Constantinople news had reached Manuel through his agents that the Venetian fleet was decimated by plague and paralysed; there was no need for the emperor to make any concessions. As Dandolo and his fellow envoys waited in the city, their mission in limbo, a strange incident took place. It appears that when Dandolo was out in the city one day he became involved in a fracas and his sight was damaged. (A story was later put about, perhaps by Dandolo himself, that the emperor himself had blinded him.) For the rest of his long life Dandolo was to manipulate his apparent sightlessness to his advantage; but whatever the truth of the episode, there is no doubting his real hatred of the Byzantines, and he harboured it for the rest of his life.

When Manuel heard that the Venetian fleet had struggled back home, he pursued his advantage with withering scorn.

Your nation has for a long time behaved with great stupidity. Once you were vagabonds sunk in abject poverty. Then you sidled into the Roman [i.e. Byzantine; the emperors always claimed, with some justification, to be direct successors of the Roman emperors] empire. You have treated it with the utmost disdain and have done your best to deliver it to its worst enemies [the Hungarians] as you yourselves are well aware. Now, legitimately condemned and justly expelled from the empire, you have in your insolence declared war on it – you who were once a people not even worthy to be named, you who owe what prestige you have to the Romans; and for having supposed that you could match their strength you have made yourselves a general laughing stock. For no one, not even the greatest powers on earth, makes war on the Romans with impunity.

He could not have been more wrong. Dying in 1180, he did not live to see the Venetian revenge; and indeed, at first there seemed no chance that any would be exacted. Manuel’s successors, shrewd and realistic diplomats in the best of Byzantine traditions, realized the importance of getting trading relationships back to normal, and in 1187 a new treaty was negotiated with Venice in which the city’s privileges were restored and the Venetians’ rivals, the merchants of Pisa and Genoa, excluded from imperial trade. Enrico Dandolo, who could be trusted by the Venetians never to betray their interests, travelled back to Constantinople as one of the envoys in the complex and tricky negotiations which any treaty with the Byzantine empire involved. His achievements were well appreciated by his city and in 1192, probably aged well over seventy and with little or no sight left, he was elected doge. Few suspected that the ambition to humiliate Constantinople still consumed the old man.

This was the age of the crusades. The Second (which dragged on from the 1140s to the 1180s) and Third (1189–92) had ended in failure and in 1201 a new, comparatively young (aged thirty-seven at his accession three years earlier) and untested pope, Innocent III, called a fresh crusade. A band of European noblemen, most of them from France and the Low Countries, gathered under the leadership of one Baldwin of Flanders, and another contingent of barons and supporting troops assembled in southern Italy. The overland route to Jerusalem being considered too hazardous for a large army, the decision was made to invade the Holy Land through Egypt. This meant that a fleet had to be found to convey the crusaders to the Egyptian coast – and here the Venetians found their role. They had well-equipped shipyards and could meet the demand for transport. So Dandolo agreed to provide the ships, but the harsh contract he demanded made no concessions to the ostensibly spiritual motive for the enterprise. Yes, a fleet and a year’s supplies would be provided; but it would cost 85,000 silver marks, payable in any circumstances. The crusaders agreed.

Then every organizer’s nightmare occurred. The Venetians fulfilled their side of the bargain and the boats were ready by the agreed date of June 1202 – but the crusaders had been hopelessly optimistic and only a third of the hoped-for 33,000 knights turned up to fill the boats. There was no way they could honour the contract, even through raising loans on the Venetian exchange to pay in instalments. From June to November 1202 the knights waited in some embarrassment on the Venetian Lido, until Dandolo, who may well have realized all along that he could manipulate the contract to his own advantage, made a new proposal. Some of the sum could be remitted if the crusaders would stop off on the way to Egypt to recapture the city of Zara, on the Dalmatian coast, which had rebelled against the Venetians and placed itself under the protection of the Hungarians. It was a particularly cynical ploy in that the king of Hungary had been one of the few Christian monarchs to have given support to the crusade. In Rome, Innocent III was now becoming aware that he had entangled himself in political manoeuvres over which he had no control, and he announced in some desperation that he could support the crusade only if no Christians were attacked on the way to the Holy Land. But events overtook him when the Doge, with an instinct for the theatrically effective gesture, took centre stage. He knelt at the high altar of St Mark’s, where a pilgrim’s cross was fixed to his hat, and then, in the Piazza outside, he proclaimed that despite his age and disabilities, he was the only one able to lead the crusade effectively. He would provide fifty galleys of his own, and he called on Venetians to come with him. There was to be, however, no renegotiation of the original contract with the crusaders. The money, whether offered in cash or military service, was still to be paid.

The fleet set off in October, priests chanting from the mast tops as it left. ‘Never before had such rejoicing or such an armada been heard or seen … verily did it seem that the whole sea was as warm and ablaze,’ wrote one of the crusaders. Progress down the Adriatic was at a stately pace, Dandolo stopping off at ports to display his great fleet to subject cities. Zara was eventually reached and reconquered after a five-day siege. It was now too late in the year to risk a crossing of the Mediterranean, and the crusaders spent the winter of 1202–3 in the city. By now many were becoming uneasy about the enterprise, especially when they learned to their horror that the Pope was threatening to excommunicate them all for their attack on fellow Christians in Zara. In the end, Innocent, who was learning fast about the realities of political life, confined his bull of excommunication to Dandolo and the Venetians alone – and even then the papal legate who was accompanying the fleet, knowing that if the verdict were delivered it would bring the collapse of the crusade, suppressed the bull when it arrived.

Then another diversion presented itself. The throne of the Byzantine empire was in dispute; one of the contenders was Alexius Angelus, the son of an earlier emperor, Isaac II, who had been deposed, blinded and imprisoned by his own brother, Alexius, now the emperor Alexius III, in 1194. Alexius Angelus naturally felt that his claim to the throne was strong and realized that the Venetians and the crusaders might be able to help him. He put forward his own proposal to them. If aid were given him to take the throne, he would support the crusade with 10,000 troops and 200,000 marks, well above what was needed to settle the Venetian contract. Perhaps the most attractive part of the offer, however, was his promise to reconcile the east to Rome, in effect to accept the supremacy of the pope over the Byzantine church.

Attractive as they were, Alexius’ promises did not convince everyone. ‘Wild promises of a witless youth’ was the opinion of Niketas Choniates,* an official at the Byzantine court whose record of these years is invaluable. It is probable that Enrico Dandolo, who knew Constantinople, its resources and its ways very well indeed, understood from the outset that all these promises were unlikely to be fulfilled, even if Alexius were enthroned. So did the pope. While the bishops in the fleet, eager to see a reunion of east and west, supported the new enterprise, Innocent condemned it. He recognized that the offer of reunion was likely to get nowhere – a young emperor could not simply slice through the tangle built up by centuries of suspicion and disagreement between east and west over Christian doctrine and sign his church over to Rome – and so he refused to rescind the excommunication of the Venetians. But it was all too late. The fleet, now with Alexius himself on board, had left Zara before the papal condemnation had arrived, and had since reached Corfu. Ominously, however, a demonstration here against Alexius was a forewarning that his elevation to emperor could not be taken for granted.

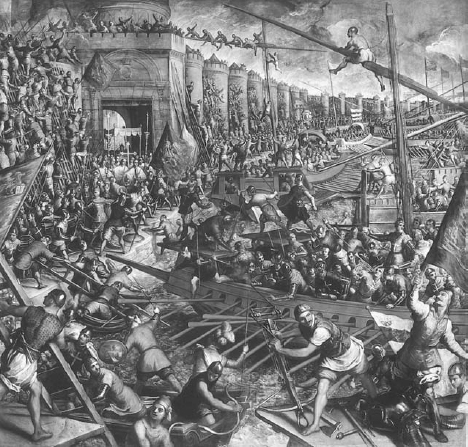

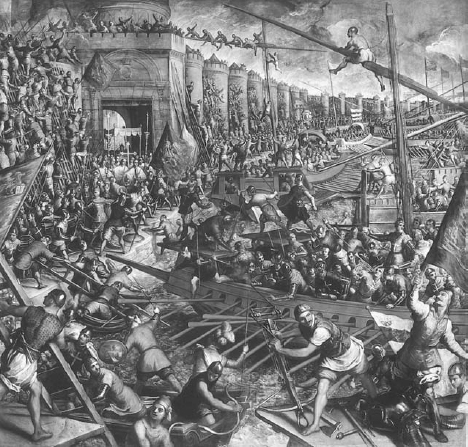

Now beyond papal control, the fleet sailed on, round Greece and up through the Aegean. In June 1203 it entered the Hellespont and soon the great walls of Constantinople, built some eight hundred years before by the emperor Theodosius II, were in view. Adorned with icons of the Virgin Mary, which were believed to protect the city in times of crisis, they had repelled all invaders in the past and the ‘sitting’ emperor’, Alexius III, must have hoped they would do so again. He was unpopular with his people, he had little in the way of a fleet and his army was made up largely of mercenaries; but his hopes of survival were raised when Alexius Angelus was ceremonially paraded before the walls in Dandolo’s grand barge. The pretender’s rash promises must have gone before him as he was greeted with abuse from the walls and stones were rained down on him.

Dandolo now took the initiative in proclaiming that the throne would have to be fought for. This may have been what he was hoping for all along; certainly his was the first barge to land beneath the walls. While the crusaders stayed encamped further from the city, the Venetians stormed the walls and to everyone’s surprise had soon captured many of the towers. This dealt an immense psychological blow to the defenders, and resistance collapsed. Alexius III fled with his jewels and the people brought out Isaac from prison as his replacement. Blind and by now senile after nine years in prison, he had no chance of holding the throne – and so it was that his son, Alexius Angelus, despite being no more popular than his predecessor, became the emperor Alexius IV.

Now Enrico Dandolo tightened his grip. He insisted that all Alexius’ promises be fulfilled. Alexius scoured the treasury and managed to settle the debt the crusaders owed to Dandolo; but this sum was still far below what had been promised, and the crusaders were left without even the provisions to go further. Alexius found himself in yet deeper trouble when his attempts to bring the Greek church under the authority of Rome were greeted with outrage. Serious rioting broke out between the Catholic Latins – the Venetians and other Italians living in Constantinople – and the Orthodox native Greeks. Alexius could not survive without the support of the crusaders – but they were insisting that he honour his promises before they helped him further. He ended up isolated, and in January 1204 he was in his turn deposed and then strangled. The Greeks proclaimed a new emperor, the son-in-law of Alexius II, who took office as Alexius V. This Alexius decided the only way out of the stand-off was to clear the Latins out once and for all. In the rising tension, many fled the city to the crusaders’ camp.

The battle lines were now drawn. The crusaders had lost the man they had come to install as emperor, while any religious justification for the expedition to Constantinople had been jeopardized by the determination of the Greeks not to surrender to the supremacy of Rome. Lacking even the means to sail home, the crusaders threatened to fight to win what they were owed. Once again it was Dandolo who saw his opportunity to shape the outcome, in fact to transform the expedition into an instrument for destroying the Byzantine empire itself. It was he who crafted a treaty between the Venetians and the crusaders to provide for its dismemberment. Constantinople would be conquered, the doge would have first call on the spoils of the opulent city, up to three-quarters of what was taken, and a joint committee of crusaders and Venetians would elect a Latin emperor (who would, of course, then transfer the religious allegiance of the empire to Rome). The new emperor would be left in charge of a truncated empire, only a quarter of the existing provinces, while the remaining three-quarters would be distributed between the crusaders and the Venetians. There was never any doubt that the Venetians would select territories which would sustain their trading networks. Any qualms the crusaders might have had in serving the interests of the Venetians were settled by their priests, who told them of the glory they would gain by extracting the many relics of the city from heretics, as the Greek Orthodox Christians certainly were in Roman eyes.

The attack was launched on 9 April 1204. Despite some resistance by the new emperor, several of the great gates of the city were forced and by 13 April Alexius V had fled. The leaders of the crusade moved into the imperial palaces and gave their men leave to pillage the city. Their booty was supposed to be collected for orderly dispersal, but discipline soon broke down and Constantinople was given over to chaotic looting. Three disastrous fires swept through the city. Churches, including Constantine’s resting place, the Church of the Holy Apostles, were sacked; even the corpse of the great emperor Justinian was violated, the jewels around the well-preserved body snatched from it. Perhaps two thousand died in the violence.

There is a heart-rending account of the sack from Niketas Choniates. As an official who had worked his way to the top of the imperial household, Niketas had acquired his own palace, three storeys high and embellished with gold mosaics. At first he sheltered there, but it was destroyed in the second great fire. Deserted by his terrified servants, Niketas and his young family (he had one son small enough to need carrying and his wife was pregnant) had to struggle through the streets in the company of a few loyal officials and friends.

The Fourth Crusade, 1204. The elderly doge Enrico Dandolo urges the crusaders on from his barge as they attack the walls of Constantinople. A sixteenth-century reconstruction in the Doge’s palace by Palma il Giovane. (Palazzo Ducale, Venezia/Scala)

We were like a throng of ants passing through the streets. The troops [the crusaders] who came out to meet us could not be called armed for battle, for although their long swords hung down alongside their horses, and they bore daggers in their sword belts, some were loaded down with spoils and others searched the captives who were passing through to see if they had wrapped a splendid garment inside a torn tunic or hidden silver or gold in their bosoms. Still others looked with steadfast and fixed gaze upon those women who were of extraordinary beauty with intent to seize them forthwith and ravish them. Fearing for the women, we put them in the middle as though in a sheepfold and instructed the young girls to rub their faces with mud to conceal the blush of their cheeks … We lifted our hands in supplication to God, smote upon our breasts with contrite hearts, and bathed our eyes in tears and prayed that we all, both men and women, should escape those savage beasts of prey unharmed.

Later Niketas describes how he managed to save one girl from rape by shaming her attacker in front of a leader of the crusaders.

In a later section of his account Niketas tells how, after he had found refuge and his wife had been delivered of their child, he returned to the city to find a systematic destruction of art treasures under way. The hippodrome appears to have been the scene of the greatest depredations. Many of the statues set up there by Constantine were dragged off by the crusaders to be melted down, among them the Hercules, a she-wolf with Romulus and Remus, and an eagle and serpent. A head of Hera, the wife of Zeus, alone needed four yokes of oxen to cart it off. Nothing seemed able to quell the rapacity of the crusaders – even a most beautiful bronze of Helen, relates Niketas, was unable to exercise her charms on those who consigned her to the flames. Perhaps, he suggested, the Venetians, playing on their supposed Trojan origins, wanted revenge for the destruction of Troy which her presence there had brought about.

Niketas had no doubt that Enrico Dandolo was the driving force behind the sack and what followed. He was ‘not the least of horrors … a creature most treacherous and extremely jealous of the Romans, a sly cheat who called himself wiser than the wise and madly thirsting after glory as no other’. Dandolo, says Niketas, had grasped the fact that any attack on Constantinople by the Venetians alone would have brought disaster down on his head, and so he involved others ‘whom he knew nursed an implacable hatred against the Romans [i.e. the Byzantines] and who looked with an envious and avaricious eye upon their goods’. From the beginning, Niketas was convinced, the crusade had been a mask for Dandolo’s ambitions for revenge upon the empire that had treated him with contempt nearly thirty years earlier.

What happened next bore out Niketas’ suspicions. Once again it was Dandolo who took the leading part in enforcing the treaty he had made with the crusaders to Venice’s advantage. He did not wish to become emperor himself, preferring to see an acceptable candidate appointed from among the leading crusaders, and, after some wrangling between rival claimants, Baldwin of Flanders was elected. (Dandolo’s influence is suggested by the use of an election; such a procedure, well established in Venice, was unknown in northern Europe.) The Venetians then insisted that in return for acquiescing in a Latin emperor they should have the right to appoint the patriarch of the city; and a Venetian, Thomas Morosini, ‘of middle age and fatter than a hog raised in a pit’, as Niketas described him, duly took office. The doge was to receive the title of ‘despot’ and to have the privilege of not having to pay homage to the new emperor and his successors.

Now the conspirators could move on to the division of the empire, and here Dandolo used his intimate knowledge of the Aegean to gain vital staging posts for Venice. Of the city itself three-eighths, including the docks, was to be Venice’s, the other five-eighths the Latin emperor’s. To the west of the city a stretch of Thrace across from Adrianople up to the Sea of Marmara went to Venice, as did all the islands of the west coast of Greece, much of mainland Greece including the peninsulas jutting out from the Peloponnese, and several well-placed Aegean islands: Salamis, Aegina, Andros and, most significant of all, Crete. Supremacy in western Greece gave Venice full control of the entrance to the Adriatic, a vital strategic advantage. The crusaders gained much of the rest of the empire.

The outside world had to come to terms with these events as best it could. One of Baldwin’s first tasks was to feed the pope with a version of events which stressed the happy reunion of the long-separated Christian churches. Innocent’s initial joy did not survive the details of the terrible destruction that had accompanied the reunion and the news that his own legate had not only lifted the excommunication of the Venetians but absolved the crusaders from continuing to the Holy Land. He was particularly stung by the appointment of Morosini as patriarch by a Venetian doge who had still been under excommunication at the time. But realpolitik soon took over. In 1205, after some sober reflection, Innocent announced that now he had heard the ‘true’ version of events it was clear to him that Morosini had been fairly selected as patriarch, that his legate had had the right to lift the excommunication and that Dandolo had indeed done such great service to the Christian world that God would release him from any further duty to carry on the crusade. Meanwhile many of the subjects of the empire resisted their new overlords and its neighbours took the opportunity to settle old scores. In April 1205 Baldwin was captured by the Bulgars at Adrianople in Thrace, and when news of his death in captivity came through one of Morosini’s first official engagements was to crown Baldwin’s brother, Henry, as the new Latin emperor in 1206.

With the sack completed, it might have been considered time for Dandolo to return home. He had achieved all he had plotted for and the fruits of victory had been immense, not only in terms of immediate booty but in the consolidation of Venice’s trading empire for the future. His vigour, however, remained undiminished and he even led his own troops in an expedition to help Baldwin’s shattered army extricate itself from its entanglement with the Bulgars. It may be guessed that in these last months of his life Dandolo relished the freedom to dictate events in a way that the Venetian constitution, which, in the middle of the previous century, had reduced the powers of the doge considerably and transferred power to a Great Council, would never have allowed him to do at home; and so he appointed his son Raniero as regent in Venice and stayed in the east. Even after his death in 1205 his body was never returned to Venice, and still lies in the church of Santa Sophia, its burial place marked by a simple engraved slab.

Before his death Dandolo had made a selection of some of the treasures of Constantinople that he would like to send back to Venice, and these were to be followed over the years by a steady stream of plunder as the Venetians abused their control over their part of the city. Studies of the documentary records and evidence from what actually survives in Venice allow us to compile a list of the loot. First, there were the sacred relics which Constantinople, as the capital of a Christian empire, had accumulated over the previous nine centuries. Dandolo himself is associated with the choice and removal of the head of John the Baptist, drops of Christ’s blood, a nail from his cross, part of the pillar at which he was flagellated, St George’s arm, and a cross carried into battle by the emperor Constantine. (Another relic, the crown of thorns, was used as security for a loan to the crusaders until the saintly King Louis IX of France was persuaded to redeem it. He housed it magnificently in the Sainte-Chapelle in Paris.)

Among the bodies of saints that were dispatched to Venice in the next few years were those of St Lucia, St Agatha, St Symeon, St Anastasius, St Paul the Martyr – even, according to some reports, St Helena, the mother of Constantine (although, unlike most of the others, this cannot be traced in Venice). Then there were other items of treasure: jewelled caskets, precious vessels, even ancient Egyptian vases of polished stone, which were probably chosen because of their quality and rarity and the ease with which they could be shipped home. These treasures, many of them pagan, came to rest with the relics in the Treasury of St Mark’s. Other treasures of pagan origin were taken to Venice and then transformed into Christian symbols. A head of the Hellenistic period (323–31 BC) was joined to a Roman torso to form the statue of St Theodore which, as described earlier in this chapter, was later placed with his symbol, a crocodile, on one of the ancient columns from Alexandria in the Piazzetta. The neighbouring column was topped by a winged lion of St Mark which was created from a chimaera brought from Constantinople, possibly of Persian origin and dating from perhaps 300 BC, to which wings were added by the Venetians. Then, in the established tradition of finding marble to embellish Venetian buildings, there were superior ‘building materials’. Two finely decorated columns, later to be placed at the southern entrance of St Mark’s, where they still stand, came from the sixth-century church of St Polyeuktos which, although disused by the twelfth century, had originally been one of the most sumptuous in Constantinople. Excavations in modern Istanbul have discovered similar carvings on the site of the church and have also shown that it was stripped of its marble at just about the time of the Venetian conquest. Then there was a mass of sculptured reliefs, depicting subjects ranging from Hercules to the Christian saints, and pieces of beautiful marble from Santa Sophia and other churches. (The Dandolo family allocated much of the marble to the rebuilding of their family palace in Venice.) With all this went a set of bronze doors, datable to the sixth century, which were to be placed in the central doorway of St Mark’s. The Venetians knew quality when they saw it.

Another group of seized statues was linked specifically to Constantinople’s imperial past. A large bronze of a ruler – one of the early Christian emperors, possibly Marcian (emperor 450–7) – never reached Venice: the ship carrying it from the east was shipwrecked off southern Italy and the statue still remains where it was rescued, at Barletta. Then there are the four soldiers in porphyry which are now embedded in the southern wall of St Mark’s, on the outside of the Treasury. There are two pairs; each soldier has one hand on his sword while the other clasps his fellow on the shoulder. Byzantine sources suggest that they came from a building known as the Philadelphion, and excavations in Istanbul again confirmed the provenance when a piece of porphyry which proved a perfect match was found close to where this building had stood. The soldiers are now considered to be Diocletian and his fellow tetrarchs, joint rulers of the empire in the late third century, although it appears that when they were in Constantinople they were believed to be the four sons of Constantine. Either way they are linked to Constantine’s family for his father, Constantius, was one of the tetrarchs. On the same wall of St Mark’s, up on the railing at the south-western corner of the loggia, is another of the spoils of 1204: a porphyry head of an emperor, believed by many to be Justinian. Marbles and jewels were also taken from the Church of the Holy Apostles, the burial place of Constantine and many of his successors, although none of these can be identified in Venice today.

The accounts of the sack tell us that Dandolo himself picked out the four horses which were to come to rest at St Mark’s. There is one possible reason, apart from their obvious quality, why Dandolo may have been drawn to the horses. In the fifth century BC the Veneto was considered one of the best areas in which to find chariot horses; it is possible that memories of this trade were still alive and were known to Dandolo, perhaps having been passed on to him on one of his visits to Constantinople.* If this was what attracted him to horses, which horses might he have chosen? Many commentators have assumed without much discussion that he chose the team which had been set up on the starting gates of the hippodrome by Theodosius II. We know that these were still in place in 1162, when Niketas Choniates wrote of ‘four gilt-bronze horses, their necks somewhat curved as if they eyed each other as they raced round the last lap’, and at first sight they do seem the most likely choice. There are four horses, apparently without a chariot, and they are gilt. Unlike many of the more accessible bronzes in the hippodrome itself, they would have been difficult to reach, so the mob may have spared them and left them available for Dandolo to take.

However, there are also grounds for doubt. The horses now in St Mark’s can hardly be described as ‘racing’ – they are clearly, with three feet on the ground, standing – and on these grounds as early as the eighteenth century a Göttingen professor, Christian Gottlieb Heyne, dismissed the claim that the starting-gate horses were the same as those on St Mark’s. It has also been claimed, by the Italian scholar Vittorio Galliazzi, that in their original setting the horses were in two pairs with the heads of each looking outwards, and that it was only when they were placed on St Mark’s that the heads of the two outer horses were detached (they are separate castings, so this would not have been difficult) and transposed to make two pairs, each with their heads looking inwards towards each other. As we shall see in the next chapter, the art historian Michael Jacoff provides a reason why the heads needed to be changed over when the horses were set up on St Mark’s. If Galliazzi and Jacoff are right, then these horses would not have been ‘eyeing each other’ in their original setting and so could not have been those on the starting gates.

One can take a different line and highlight Dandolo’s own obsession with the humiliation of Constantinople. If he merely wanted high-quality statues for their own sake, there would have been many, especially from the area of the hippodrome, that he could have saved from destruction. We may guess instead that he wanted to appropriate something which was symbolic of the core of the city’s identity. The most prestigious quadriga of the three recorded in the eighth century was surely that at the Milion which accompanied the statue of Zeus Helios (or Constantine in that guise). This set of four horses, with all its associations with the founding of the city and its founder himself, would have provided all the resonances of the victory that Dandolo could wish for. Yet we cannot fix on these horses with absolute certainty either, for they were described by the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai as being ‘driven headlong’, again hardly an accurate representation of the St Mark’s horses; and so one might equally choose the third of the sets of horses, that seen in the hippodrome itself in the eighth century. These were also associated with the foundation ceremonies of the city. However, the original Greek word used in the Parastaseis to describe them as a group is ‘yoked’, and there is no evidence from the St Mark’s horses of any fittings for yokes on their bodies.

So the identification of the St Mark’s horses is not straightforward. And yet, how better to humiliate Constantinople and its empire than to take a treasure which represented not only its august founder but the moment of the city’s foundation itself, and to add it as the crowning piece of the plundered imperial statuary? My own guess would be that Dandolo chose the horses from the Milion. This would explain why the scholarly Bernardo Giustiniani wrote in 1493 of the horses as being ‘all made for the chariot of the sun’. If they had been detached from the chariot of Zeus Helios and brought to Venice, then the memory of their original setting may well have travelled with them.