DESPITE THE ENORMITY OF THE SACK OF CONSTANTINOPLE, the Venetians seem to have been untroubled by guilt. In Martino da Canal’s Estoires de Venise, written between 1267 and 1275, the sack is presented as a justified conquest and Dandolo praised for it. ‘It was through the wisdom of this great man that a city as grand as Constantinople was taken; and this’, Canal adds somewhat unscrupulously, ‘he did in the service of the Holy Church.’ Great canvases by Jacopo Palma il Giovane, hung when the Doge’s Palace was redecorated in 1587 after a fire, show Dandolo before the walls of Constantinople, urging on the Venetians from his barge. By that time, of course, the Venetians knew what they were really celebrating: the acquisition of a trading empire which had brought them dominance in the eastern Mediterranean. Even though they were to lose their foothold in Constantinople itself in 1261, when the city was regained by Greek emperors, the thirteenth century was to be one of great prosperity for Venice.

That prosperity was to be reflected in the transformation of St Mark’s. The eleventh-century basilica had been fronted in brick, but by the middle of the thirteenth century the western façade had been remodelled to provide an opulent backdrop to the Piazza, and the domes above it raised to the form visible today. The remodelling goes hand in hand with a rise in status of the procurators of St Mark’s, those responsible to the doge for the care and embellishment of the fabric of the basilica. By the 1260s they are housed in the Piazza itself and are increasingly responsible for the Piazza’s own buildings and other estates in the city. The office of chief procurator was so prestigious that it could even serve as a stepping stone to that of doge itself.

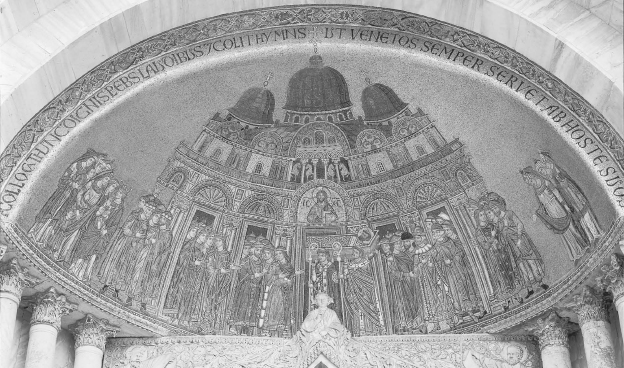

The work on St Mark’s set in hand by the procurators was extensive. A narthex, fronted by five arches reminiscent of the triumphal arches of Rome, was built round the western façade and this was faced with reused marbles, mosaics and columns, many of them from among the loot brought from Constantinople. Unfortunately only one of the original mosaics, that over the Porta San Alipio on the far left, showing the arrival of the body of St Mark in front of the basilica itself, survives, and this is not from Constantinople but Venetian work dating from about 1267; the others are much later restorations or replacements. This façade was dedicated to religious themes – on either side of the central ‘triumphal’ arch a relief of a saint was added, St Demetrius on one side and St George on the other. Both are warrior saints, as if to proclaim spiritual support for Venice’s new status as a city of conquerors. Moving outwards from the centre, between the first and second doors there is a relief of the Angel Gabriel appearing to – in a similar position on the other side – the Virgin Mary orans, her arms uplifted in prayer, the standard Byzantine representation. They were no doubt placed on the façade as a reminder of the legend that Venice was founded on the day of the Annunciation. More perplexing are two reliefs of the pagan god Hercules, represented in his labours, attached at the far ends of the façade. They will reappear in the story.

On the south side of the basilica the mood is somewhat different. The porphyry statues of the tetrarchs were placed on the corner wall of the basilica’s Treasury (close to what was originally one of the main entrances to the basilica) while the head of another Byzantine emperor, probably Justinian, was, as we have seen, set up on the end of the loggia, the platform which ran along the top of the narthex. Some of the finest marble reliefs and slabs from Constantinople were embedded in the wall of the Treasury. When visitors landed on the Molo this was the first they would see of the basilica, and the façade seems deliberately to have been designed as a showcase of imperial Venetian pride. It was here in the Piazzetta that extra monuments were placed as they arrived in the city. The two pillars from the Church of St Polyeuktos were put in their present place in front of the southern façade in 1258. This somewhat isolated position may seem strange, but the Old Testament description of Solomon’s Temple in Jerusalem (1 Kings 7: 15) mentions two bronze pillars ‘in the vestibule of the sanctuary’. Both are described (v. 20) as having pomegranates on the moulding, and pomegranates are also carved on the St Polyeuktos pillars. It is possible that the Venetians, who had trading links with Jerusalem, were attempting to recreate Solomon’s Temple, with all its ancient spiritual resonances; indeed, the suggestion is reinforced when we find that there is a relief of the Judgement of Solomon nearby on the wall of the Doge’s Palace.

The stump of a porphyry column, the so-called Colonna del Bando, captured from the Genoese in the city of Acre in 1257, was set up at the corner of the basilica in 1265. It served as a base from which to display the severed heads of criminals, ‘though the smell of them doth breede a very offensive and contagious annoyance’, remarked the Englishman Thomas Coryat when he visited Venice in 1608. The Colonna had its day of glory, however: on 14 July 1902, when the Campanile collapsed and the Colonna helped prevent the rush of brick and stone reaching St Mark’s. Meanwhile the Treasury of St Mark’s was crammed with an assortment of loot from Constantinople, including the most sacred relics possible, those directly associated with the passion of Christ. Alongside them were placed the Egyptian vases and Greek vessels showing Dionysiac revels, which the Venetians had carried off with the relics. Sacred and profane still exist happily together in the Treasury today.

Some time in the middle of the thirteenth century the four horses selected by Enrico Dandolo were hauled up on to the loggia above the central door of the basilica. They had been brought back to Venice, on Dandolo’s orders, in the personal care of one Domenico Morosini. The story goes that during the voyage a foot was knocked off one of the horses and the Morosini family was allowed to keep it. It passed down the family and was mounted on a bracket on the façade of one or another of their various palaces as a symbol of the family’s distinguished history and connection with the sack of Constantinople. When the horses arrived in Venice they were placed at first in the Arsenale, the naval dockyard. It seems no one knew what to do with them: with Dandolo’s death in Constantinople, the reasons why he had selected the horses and any plans he might have had for them must have been lost. There is even a story that they came close to being melted down but that some visiting Florentines, more sophisticated than the Venetians in such things, were horrified at what was about to be destroyed and urged that they be saved.

This nineteenth-century terracotta is believed to be the copy of a much earlier silver plate commemorating the presentation of the horses to a personification of Venice by Enrico Dandolo. (Comune di Treviso, Ereditá Lattes/NV. n. 945)

The mosaic from the Porta San Alipio on the façade of St Mark's dates from c.1267 and is the earliest representation of the horses in place on the loggia. The scene is anachronistic: it shows the arrival of the body of St Mark at the basilica in the ninth century. (S. Marco, Venezia/Scala)

A range of dates between the 1220s and the 1260s has been suggested for the moment when the horses were actually raised up on to the loggia, but they were certainly in place by 1267, when they were depicted in the mosaic over the Porta San Alipio. There the horses are in the same position over the central door as they are today, divided into two pairs, each horse looking towards its immediate neighbour, with an open space left between them. (However, the mosaicist has transferred the raised leg of the inner horses from the outside to the inside, presumably to create a more symmetrical pattern.)

One’s first response to the horses’ elevated position overlooking the Piazza is that they are being shown off as plunder, and this is reinforced by the ‘triumphal’ entrance arch above which they stand. While it is hard to believe that this was not one of the impulses behind their display, the west front of St Mark’s was, as we have seen, a ‘religious’ rather than ‘political’ façade, and it may be that the horses also represented some kind of religious statement. The problem lies in identifying what it might have been. In the Old Testament there are certainly chariots but it is not always clear by what they are drawn. In the vision of the prophet Ezekiel, for instance, there is a chariot drawn by four animals, but these are strange composite creatures, of human form but with the hooves of oxen and four wings. Then there is the fiery chariot which takes Elijah up to heaven (2 Kings 2). The Hebrew word used to describe it is not associated with any specific number of horses, and when the Hebrew was translated into Greek in the third century BC the Greek word used was harma, a general term for chariot, again with no association with a specific number of horses. Yet when the fourth-century scholar Jerome went back to the Hebrew as the basis for his Latin version of the Old Testament (known as the Vulgate, this remained the Roman Catholic Church’s ‘official’ version for centuries), he decided to emphasize Elijah’s status by translating ‘chariot’ as quadriga. For Jerome, nothing less was suitable for the prophet. Whether Jerome knew it or not, the same approach had been taken in art: at least two early Christian sarcophagi have reliefs which show Elijah being taken up to heaven in a classical quadriga with its four horses.

Centuries after Jerome, in the twelfth century in fact, just a few years before the sack of Constantinople by the Venetians, we find quadrigae, this time actual chariots drawn by four horses, used in Constantinople in recreations of that most ancient ceremonial ritual of the Roman world, the triumph. Niketas Choniates, in his history of the events of this century, tells how the Byzantine emperor John inflicted a massive defeat on the Turks and then, in 1133, mounted a triumphal procession, but this time one set in a Christian context, in Constantinople. A silver-plated chariot was constructed and decorated with semi-precious jewels.

The splendid quadriga was pulled by four horses whiter than snow, with magnificent manes. The emperor himself did not mount the chariot [as would have happened, of course, in ancient Rome] but instead mounted upon it the icon of the Mother of God … To her as the unconquerable fellow general, he attributed his victories and ordering his chief ministers to take hold of the reins and his closest relations to attend to the chariot, he led the way on foot with the cross held in his hand.

This was not an isolated incident. When the emperor Manuel won his great victory over the Hungarians in 1167, he too decided to hold a Roman-style triumph complete with captives and plunder. The population of Constantinople was assembled to watch from specially constructed platforms as the procession wound its way through the streets. ‘When the time came for the emperor to join the triumphal procession, he was preceded by a gilded silver chariot drawn by four horses as white as snowflakes, and ensconced on it was the icon of the Mother of God, the invincible ally and unconquerable fellow general of the emperor.’ The procession eventually reached Santa Sophia, where a service of thanksgiving was held before the emperor retired to his palace and then, ‘unstringing himself like a bow from the excessive tension, he relaxed at the horse races’.

Reliefs of the prophet Elijah ascending to heaven in a quadriga are known from as early as the fourth century AD. This portrayal, from the cathedral in Anagni, central Italy, is shown in a fresco dating from the thirteenth century and thus roughly contemporary with the placing of the horses on St Mark’s. It reveals how quadrigae could be incorporated into Christian art. (The Art Archive)

So the quadriga could be transferred into Christian contexts; and the art historian Michael Jacoff has suggested yet another which seems to be of particular relevance to the horses of St Mark’s. He has found references which compare the four evangelists with four horses which pull ‘the quadriga of the Lord’. As Jerome wrote in a letter of 394, ‘Matthew, Mark, Luke and John are the Lord’s team of four, the true cherubim or store of knowledge.’ In the ninth century another source (Haimo of Auxerre) proclaims that ‘the preaching of the Gospel rests upon the authority of the four Evangelists and the four Gospels are like the four of the quadriga of the New Testament, which Christ himself as charioteer controls, himself guiding and drawing up the chariot of the Gospels’. There even exists a link to Venice in an eleventh-century sermon by St Peter Damian, on the theme of Mark, and possibly even preached in St Mark’s, which describes the chariot of Aminadab, from the Old Testament Song of Songs, as ‘a forerunner of the quadriga of the gospel of Christ’, again with Christ as the charioteer. While there is no surviving direct reference to the St Mark’s horses themselves as the ‘quadriga of the Lord’, the image was certainly current in Venice.

Seeking support for this view, Jacoff embarked on some architectural detective work. The placing of the horses on the loggia with a wide gap between the two pairs is unusual and would have made any relationship with a real chariot impossible. Was there a specific reason for leaving a space? In the present setting there does not seem to be, but the window behind the horses was placed there only in the fifteenth century. Before this, according to the Porta San Alipio mosaic, there were columns flanking the horses but what else was in the vicinity is not clear. However, at the Porta dei Fiori on the northern side of St Mark’s there are five reliefs, one each of Christ and the four evangelists, which date from the thirteenth century. It has long been acknowledged that they are out of place there and were probably transferred from somewhere else in the church. They could actually fit in the space above the horses, with the relief of Christ in the centre just under the arch and the evangelists set out below him above the columns which flank the horses themselves. It may be significant that the evangelists are set in two pairs, Luke and Mark, Matthew and John, with the members of each pair facing one another. Mark is given the most prominent position, on the immediate right hand of Christ, as, understandably, he is in other representations in ‘his’ basilica. He is designed to face outwards from Christ and towards his partner, Luke, who faces back at him. Conventionally – in ancient art, for instance – the inner horses in a quadriga face towards each other and the outer two away from each other. Here on St Mark’s, the heads of each pair of horses face each other, just as the evangelists behind them would have done. As we have seen, the heads of the horses could have been detached and changed around to make this possible.

In short, Jacoff suggests that the whole façade was designed as a unity in the thirteenth century, with the positioning of the horses designed to echo the reliefs behind them. The mosaics of the façade recorded the legends, such as the dream, which link Mark to Venice, while the horses and the reliefs placed behind and above them set Mark within the context of universal Christianity. The whole is a triumphant assertion of Venice’s status, as a conqueror whose temporal victories can be integrated with the patronage of its saint. The horses stand not only as symbols of victory but also as symbols of Mark. They are transformed within a new Christian context, just as in the Piazzetta other ancient bronzes were transformed into the statues of Theodore and Mark. (These reliefs, some the originals, some resin copies, have now been placed alongside the horses in St Mark’s.)

This carefully composed design was shattered when the decision was made in the 1420s to replace the reliefs with the large expanse of glass which fills the space today. Presumably the driving force was the demand for more light within the basilica. Three other windows, one in the north side and two in the south, were inserted into the walls of St Mark’s in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries and the western façade, open to the daylight from the Piazza, was the obvious one to exploit if yet more light were needed. This may appear to have been a ruthless destruction of both the aesthetic whole of the original and its spiritual significance, but the continual replanning of St Mark’s over the centuries shows that the Venetians were certainly not sentimental about such things. (A major ‘restoration’ of St Mark’s in the 1860s was so destructive of earlier mosaics and sculpture that an international campaign led by John Ruskin was launched in protest, and luckily succeeded in halting the project before it had reached the western façade.) Even so, there may have been some unease over removing the images of the evangelists. Two smaller representations of the four saints, one in the curve of the arch over the window, appear to have been entered on the façade at the time the window was put in, perhaps as a compensation for what had been lost.

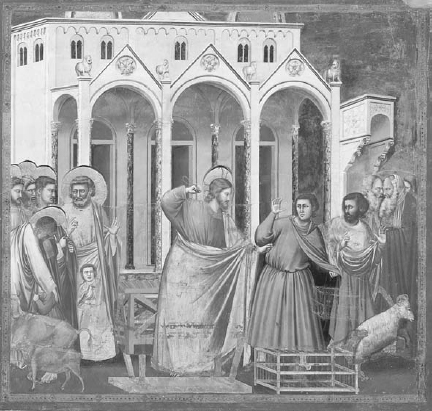

Jacoff’s argument is compelling; but would the bold display of the horses from Constantinople, even in so explicit a Christian context, ever have appeared to observers as other than primarily a triumphant display of plunder? Certainly the religious justification for the placing of the horses does not seem to have convinced everyone. We have fascinating evidence of how one of Venice’s rivals, the city of Padua on the mainland, perceived the setting of the horses in the early fourteenth century. Here the Florentine artist Giotto was fulfilling a commission to decorate the Arena Chapel (so called because it was built within the walls of the original Roman arena) for a wealthy Paduan merchant, Enrico Scrovegni. His theme was episodes from the life of the Virgin and of Christ. The Arena frescos are seen as the moment when Italian painting turned from Greek to Latin, in particular to a more realistic way of recording emotion and the natural world, and rank among the masterpieces of the early Renaissance. It has long been recognized that Giotto preferred to copy real buildings rather than to reproduce the traditional stylized images used in Byzantine art, and this is what he did when he came to depicting the Temple in Jerusalem for the fresco of The Expulsion from the Temple. One of his fellow craftsmen was the sculptor Giovanni Pisano, who had recently worked on Siena Cathedral, and it was this façade, with its pointed arches, that Giotto copied for the Temple. The original, still standing in Siena, has six sculptured animals on the pillars between the arches: two horses, one at either end; two lions in the centre; and, between the lions and the horses, an ox and a griffin. However, Giotto omits the ox and the griffin and changes over the lions with the horses so that the lions are on the outside. Then he executes a further transformation. The inner horses are none other than copies of those of St Mark’s!

Of course, Giotto may simply have been copying the horses because they were works of art which he had seen and admired. Yet if The Expulsion is explored alongside the New Testament texts that describe it, something very interesting emerges about the way Giotto portrays it. The gospels of Matthew and Mark both describe the expulsion of the money-changers and the sellers of pigeons (which were bought for sacrifice). John (2: 13–16) adds to this sellers of cattle and sheep, who are expelled by Jesus along with their animals. In Giotto’s version the only sign of the moneychangers is an upturned table, but he does include an ox and a sheep.

Clearly Giotto has used John’s version as his text. It seems that he was being tactful. The fortune of the Scrovegni family came from usury – Enrico’s father Reginald was so notorious for the practice that he is to be found in hell in Dante’s Inferno – and it has been suggested that the Arena Chapel was commissioned by Enrico in the hope of distancing himself from this unhealthy ancestry. Thus there was every good reason for Giotto to concentrate on the sheep and cattle and avoid any emphatic reference to the moneychangers. But how would this affect the animals shown on the façade of the Temple? To answer this question one has to go back to an Old Testament text, 2 Kings 23: 11. Here King Josiah is described as destroying the idols which have crept into the Temple of Jerusalem. ‘He did away with the horses that the kings of Judah had dedicated to the sun at the entrance of the Temple … and he burned the chariot of the sun.’ Christ was carrying out a similar cleansing of the same Temple, and Giotto has strengthened his point by portraying two horses to remind onlookers that they had been symbols of idolatry just as the sheep and cattle were in Jesus’ time. By portraying the horses of St Mark’s, was Giotto making the subtle point that they were emblems of pagan idolatry, and that their display had more to do with irreligious pride than with piety? This is certainly how the grand refashioning of the façade of St Mark’s with looted treasure might have seemed to Venice’s enemies.

In his The Expulsion from the Temple in the Arena Chapel in Padua (1305), Giotto displays two horses of St Mark’s, one either side of the central arch of the Temple. Was he making the point that the independent Paduans saw them as symbols of idolatry? (1990, Foto Scala, Firenze)