The artists of the Veneto, within the narrow confines of their drawings, portray the forms of beautiful antique figures in marble and sometimes bronze which are lying around or are preserved and treasured publicly and in private, and the arches, baths, theatres and various other buildings which still stand in certain places there; then when they plan to execute some new work, they examine these models, and, seeking to produce likenesses of them with artifice, they believe their labours will earn them the more praise the more nearly they manage to make their work resemble the ancient ones; so they work, aware that the ancient objects approach the perfection of art more closely than do those of more recent times.

Pietro Bembo (1470–1547), who wrote this passage in 1525, was one of those complex characters who make the study of Renaissance intellectual life so interesting. A native of Venice and son of one of its leading nobles, he wavered between religious and secular life, managing to become a cardinal despite fathering three children with one Moresina, the great love of his life. He travelled widely from one Italian court to the next, and even had a spell as secretary to the pope. He could read Latin and Greek, and was seen as one of the finest Latin stylists of his time; but he also rejoiced in writing love lyrics in Italian, though his enthusiasm for the vernacular tongue (he championed the Tuscan Italian of the fifteenth century) damaged his status as a scholar among more austere intellectuals. He was an associate of Aldus, the Venetian printer, and was responsible for creating critical editions of the Roman poets Virgil and Horace, as well as Petrarch and the great Dante. Immensely rich by the time he reached fifty, he retired to a villa near Padua which he filled with both antiques and the works of the finest artists of his day, among them Mantegna, Giovanni Bellini and Raphael. He even wrote a history of Venice, some of which was censored by the Senate when it described the characters of prominent Venetians he had known rather too perceptively.

Bembo’s comments on antique art echo those of Pliny the Elder. The antique becomes an object of admiration in its own right simply because it is a representative of the age in which art was perfected. Even something so apparently mundane as Roman pottery aroused the same adulation as the finest Greek sculpture. As early as 1282 one Ristoro of Arezzo, newly aware of discoveries of Roman ware from his native city, captured the mood of excitement.

The cognoscenti, when they found ancient Aretine vases, they rejoiced and shouted to one another with the greatest delight, and they got loud and nearly lost their senses and became quite silly: and the ignorant wanted to throw the vases and break them up. When some of these pieces got into the hands of sculptors and painters or other cognoscenti, they preserved them like holy relics, marvelling that human nature could reach so high.

This treatment of antique objects as sacred relics reached a bizarre climax in 1413 when some bones were found in a lead sarcophagus in a graveyard in Padua. Somehow they were assumed to be those of none other than the great Roman historian Livy, who was born and died in the city, and immediately intellectuals and sightseers flocked to the scene as if it were the shrine of a saint. Despite the attempts of an enthusiastic monk to break up the bones of this pagan, they were carried off into the city in procession and placed in a casket over an entrance-way to the city’s Palazzo della Raggione, the vast thirteenth-century meeting hall. The spiritual boundary between Christianity and paganism dissolved in this outburst of fervour.

If ancient art has reached perfection, then perhaps the Renaissance artist should attempt to imitate it. In a treatise on painting, the Dialogo della Pittura (1557) by the Venetian Ludoviso Dolce, an imaginary dialogue is constructed between Pietro Aretino, connoisseur, collector and champion of the Venetian Titian, who had died in Venice in 1556, and one Fabrini, who argues for the supremacy of the Florentine Michelangelo over Titian. Aretino expounds his view of ancient sculpture.

One should also imitate the lovely marble or bronze works by the ancient masters. Indeed, the man who savours their incredible perfection and fully makes it his own will confidently be able to correct many defects in nature itself and make his paintings noteworthy and pleasing to everyone, for antique objects embody complete artistic perfection and may serve as exemplars for the whole of beauty.

This approach is that of the Greek philosopher Plato, who became highly influential in the fifteenth century, notably through the works of the Florentine Marsilio Ficino (1433–99). Ficino had been installed by the great patron Cosimo de’ Medici in a Medici villa outside Florence with a mass of Greek manuscripts, and from them he compiled the first complete translation of Plato in Latin. Plato, writing in the fourth century BC, had argued that many qualities, including beauty, existed on an eternal plane in Forms or Ideas which contained the essence of the quality. No object of beauty in the natural world could equal the perfection of the Form of Beauty, although it might provide an imitation of it. Pliny, in his Natural History, had given his own example from the ancient world. One of his ‘great’ Greek painters, Zeuxis, was commissioned by the city of Croton (in Italy) to paint a Helen, a woman so beautiful that that Trojan War had been fought over her. Zeuxis selected five local girls and posed them in the nude. Of course, none of them was perfect; but he selected the best parts of each, brought them together and in his painting created the most beautiful woman he could. For Plato such a ‘beautiful woman’ might give the earthly observer a glimpse of what the Form of Beauty might be like, but, as with any object in the material world, it would always fall short of the ideal. In the Platonic tradition the artist had to labour, as Zeuxis had done, to come as close as it was possible on earth to reach the Form. This approach stood in sharp contrast to another view of the artistic mission that was also popular in the fifteenth century: that the task of the artist was to portray the natural world as it existed before his eyes. In the Platonic view the artist could, on the contrary, liberate himself from slavish copying and use his imagination to create an ideal against which any object in the natural world would seem defective.

Many Platonists believed that underlying ‘the ideal’ was a geometrical proportion: in a sculpture of a human body, for example, a canon of ideal relationships between different parts of the body. This view derived from Greece, even, in fact, before the time of Plato. A fifth-century BC sculptor from the Greek city of Argos, Polyclitus, had even written a book, the Canon, now lost, setting out the correct proportions in mathematical terms. ‘Perfection is the step-by-step product of many numbers,’ he had stated. With the rediscovery of classical writers in the Renaissance, this idea had been resurrected for architecture by the brilliant Florentine humanist Leon Battista Alberti. In his enormously influential The Art of Building, compiled in the 1440s and 1450s, Alberti argued for the existence of ideal proportions, setting out theorems that express the required geometrical ratios. We know that The Art of Building made its impact in Venice because the Torre dell’Orologio, the clock tower in the Piazza San Marco that was constructed in the late fifteenth century, conformed to Alberti’s recommended proportions for towers in its 1:4 ratio of width to height and its placing ‘at a point where a road meets a square or a forum’. In Venetian art the Platonic approach may be seen in Giorgione’s Sleeping Venus of 1510, a painting in which Venus’ sensuality appears elevated beyond the material world of desire. The dreamy landscapes and Madonnas of Giovanni Bellini convey the same Platonic sense of eternal perfection.

The horses of St Mark’s could hardly escape being caught up in the enthusiasm for ideals. They were seen as items of quality simply because of their age and provenance; but also, in so far as it was believed that the ancients were imbued with Platonism, they could also be revered as examples of the ideal horse. Moreover, if the artists in the Veneto area were looking for exemplars, there were simply no other standing horses from antiquity to copy from. If one finds a drawing, by an artist of the period who has worked or lived in Venice, of a horse standing on three legs with one foreleg raised, it is likely that it has been modelled on the St Mark’s horses. Take the Florentine artist Paolo Uccello, who had lived and worked in Venice between 1425 and 1430 and who is credited with a mosaic of St Peter, now lost, that was positioned on the top left-hand corner of the façade of the basilica, not far from the horses. We can assume that he must have observed them in detail. When he returned to his native Florence, Uccello was commissioned to paint a fresco in Florence’s cathedral in memory of Sir John Hawkwood, an Englishman who had successfully led Florence’s troops over a period of eighteen years. By chance Uccello’s original drawing survives, and it shows how much he was taken with ‘ideal’ perspectives. It is one of the earliest drawings to be made on squared paper, and much of the design is geometrical, as Polyclitus would have recommended. The top of the horse’s rump is the arc of a circle, for instance. The horse itself is modelled on one of the St Mark’s horses in so far as it has the front right foot lifted and the rear right foot well in advance (in fact further in advance than that in the St Mark’s model). Uccello is trying to dignify his horse by drawing on classical models but at the same time trying to create an ideal horse. His patrons seemed not to have approved as the fresco itself is much more natural, the rump of Sir John’s horse flat in comparison to the sketch. The link to antiquity was nevertheless preserved by painting the horse in a brownish green which suggests bronze, seen at this time as the most prestigious of ancient materials.

The first Venetian artist to incorporate the principles of the Florentine Renaissance into Venetian art was Jacopo Bellini, father of the painters Gentile and Giovanni. His contemporaries saw him as reviving the standards and proportions of ancient art. ‘How you may exult, Bellino, that what your lucid intellect feels your industrious hand shapes into rich and unusual form. So that to all others you teach the true way of the divine Apelles and the noble Polycleitus,’ as one sonnet by a contemporary put it. Two albums survive of his drawings, which he seems to have treasured and on which he worked for forty years (c.1430–70). His subject matter reflects a mixture of Christian themes (the trial and crucifixion of Christ; St George and the dragon) and those of Roman antiquity. Some show horses, in all kinds of poses, some ridden, some not, and many of these are reminiscent of those on St Mark’s in their stance or the way they hold their head. It seems indubitable that Bellini knew the horses well and used them as an ideal, adapting them as necessary in his drawings.

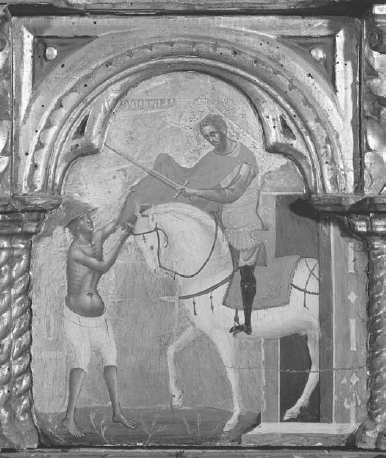

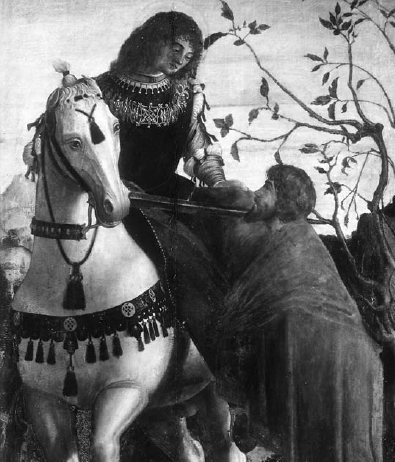

One subject which required a standing horse was that of St Martin giving his cloak to a beggar. The story goes that the fourth-century Martin, who came from Hungary, then part of the Roman empire, met a beggar and cut his cloak in half to share with him. Martin was not yet a Christian but then had a vision of Christ wearing the complete cloak, and it was this which led to his conversion. It was a popular story in medieval times and a favourite among artists. A Venetian artist looking for a model of a standing horse for a depiction of St Martin and the beggar would find one in the horses of St Mark’s. In a polyptych by Paolo Veneziano (fl. 1320–60 and the earliest Venetian painter whose work is distinguishable from others’) in the Church of San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna, Martin’s horse is indeed standing with a foreleg slightly raised, although his head is lowered, unlike those of the horses on St Mark’s. A hundred years later Martin, his horse and the beggar are found on a panel of a polyptych by the Venetian artist Vittore Carpaccio (1465–1526) in the Cathedral of St Anastasia in what was then the Venetian subject city of Zara (now Zadar in Croatia). This horse, seen from the front with its head turned towards the beggar, has a real feel of a St Mark’s horse. Perhaps, too, one can see a likeness to the St Mark’s horses in Carpaccio’s The Crucifixion of the Ten Thousand Martyrs on Mount Ararat, now in the Accademia in Venice. There are a number of horses in the picture of which four, each with a rider, stand together in the middle foreground; the one on the left in particular seems inspired by those on St Mark’s.

In the notebooks of Jacopo Bellini (compiled 1430–70) there are many representations of horses which are clearly modelled on those of St Mark’s. The horses would have been the only full-size examples of ancient horses available for a Venetian artist. (Museés Nationaux, Photo RMN–Gérard Blot)

The horses of St Mark’s provided a model for many Venetian artists. Here Paolo Veneziano (active 1320–60) uses one to portray the famous legend of St Martin dividing his cloak with a beggar. (The Church of San Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna.) (S. Giacomo Maggiore, Bologna/Scala)

A further possible echo of the St Mark’s horses can be found in the work of the German painter and engraver Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528). Dürer, who was already known beyond his homeland for his woodcuts and engravings, spent some time in Venice in the early sixteenth century, and was a favourite in aristocratic circles, though his position was never secure: awarded commissions in the city, he aroused the envy and scorn of the local artists, who several times tried to call him before the magistrates for trespassing on the preserve of the city’s guild of artists. The horse in his engraving The Knight, Death and the Devil is considered by some to have been fashioned after those of St Mark’s – but this must remain a tentative suggestion only, for by 1513, when the engraving was made, Venetians had another impressive bronze horse to use as a model: that sculpted by Andrea del Verrocchio in his equestrian statue of the condottiere Bartolomeo Colleoni, erected in the Campo dei Santi Giovanni e Paolo in Venice in 1496. Certainly by the beginning of the sixteenth century, the St Mark’s horses seem to disappear from paintings and drawings – except, of course, those, like Gentile Bellini’s Procession in the Piazza San Marco of 1496, where the horses provided the backdrop to the procession.

In fact, we can see a shift in emphasis around this time: now the horses are no longer viewed just as ideals for artists to copy but as tourist attractions. By the sixteenth century the horses begin to be cited in guides to the city as a ‘must-see’ for visitors. One Venetian, Anton Francesco Doni, compiled a list of the treasures of the city in 1549. They include works by Giorgione, Titian and Dürer, but heading the list is none other than ‘the four divine horses’. Francesco Sansovino, in his exploration of the ‘most noble and singular city of Venice’ (1581), stresses their perfection, describing them as ‘four antique horses of such rarity that even to this day they have no equal in any part of the world’. In his earlier short guide to ‘the remarkable things of the city of Venice’, produced in 1561, Sansovino had created a dialogue between a Venetian, Veneziano, and a visitor to the city, Forestiero. They enter the Piazza San Marco and gaze up at the horses:

St Martin appears again in this panel by Vittore Carpaccio (1465–1526) to be found in the cathedral at Zadar. The horses were ideal models for those who needed to show a horse standing. (Alinari Archives, Florence)

Veneziano: … It is true that they are difficult to appreciate at that height, but up there they do not obstruct the Piazza and are out of the way of the people.

Forestiero: I confess to you that truly the Cavallo of the Campidoglio in Rome is of less beauty than these, though it is larger, and that of SS. Giovanni e Paolo is not to be compared with them.

Now that travel around Italy was easier, the horses of St Mark’s began to be compared with other bronze horses. The ‘Cavallo of the Campidoglio’, the equestrian statue of the emperor Marcus Aurelius which dated from the reign of the emperor itself (AD 161–80) was certainly a worthy rival. It seems to have spent all its life in Rome. When it first emerges in sources from the middle ages it is found in front of the cathedral of St John Lateran in the south of the city, and was believed then to be of the Christian emperor Constantine who had founded the cathedral in the early fourth century. This almost certainly explains why it was never melted down in the cataclysmic destruction of pagan art which accompanied the ‘triumph’ of Christianity. By the end of the middle ages, this attribution had been challenged, and a wide variety of Roman heroes and emperors, including Hadrian, were suggested instead as its subject; but when Michelangelo transferred the statue to the Capitoline Hill (the Campidoglio) to serve as the centrepiece of his new Piazza in 1538, the horseman’s identity was still unknown, and so the statue came to be known simply as Cavallo, ‘the horse’. (The attribution to the emperor Marcus Aurelius was fully accepted about 1600.) None of this uncertainty affected the admiration of the statue. It is the model for the earliest known Renaissance reproduction of an antique statue in bronze, by the Florentine sculptor Antonio Averlino (normally known as Filarete, from the Greek, ‘lover of virtue’), possibly made in the 1430s, and more engravings were made in the sixteenth century of the Cavallo than of any other ancient sculpture. A legend records that Michelangelo was so moved by the horse that he asked it to step forward. ‘Don’t you know that you are alive?’ he challenged it. It was even said that the end of the world would be announced through its mouth.

The famous equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, one of the most influential statues of antiquity and an inspiration for sculptors from the fifteenth century onwards. (Piazza del Campidoglio, Roma/Scala)

This was an ancient statue, so was revered for its own sake; but now the Venetians had a contemporary bronze equestrian statue in the centre of their own city, Verrocchio’s monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni. To honour a military hero by presenting him on horseback was a practice with the most ancient and respectable of precedents, as the bronze of Marcus Aurelius makes abundantly clear. In the fifteenth century we find equestrian statues appearing on the tombs of Venetians as they begin to construct a Roman past for themselves. The earliest example is the monument commemorating Paolo Savelli in the Church of Santa Maria dei Frari. Here again is a horse which might be said to have been modelled on one of those on St Mark’s. The right foreleg is lifted, the head is turned slightly and although there is a full mane, in contrast to the cropped manes of the horses on the basilica, the tail is tied with a knot in the same way. Verrocchio, however, was a Florentine and looked elsewhere for his influences. According to Vasari’s sixteenth-century Lives of the Artists, Verrocchio was deeply impressed by the Marcus Aurelius, but he would also have been aware of another great bronze equestrian statue from recent times, that created by his fellow Florentine, Donatello, of the Venetian condottiere Erasmo da Narni, always known by his nom de guerre Gattalamata, ‘the calico cat’. The statue, commissioned by the Venetian Senate, was placed in front of the basilica of Sant’Antonio in Padua (where it still stands) in 1453. Donatello seems to have been determined to use the statue to dominate the square – the horse and its rider are monumental.

Bartolomeo Colleoni, the subject of Verrocchio’s statue, was a highly successful general, a pioneer, in fact, of the use of field artillery, who despite being from the mainland city of Bergamo had been made leader of Venetian troops fighting in mainland Italy in the 1460s. On his death in 1475 he left a large sum of money for a statue of himself to be erected in Piazza San Marco. The city baulked at the request but the Signoria saved its embarrassment by announcing instead that the statue would be erected in front of the building which housed the Confraternity of St Mark, next to the Church of Santi Giovanni e Paolo.

Verrocchio did Colleoni proud. The condottiere is shown riding his great charger into battle, a look of absolute determination and concentrated aggression on his face. Verrocchio died before his clay model was cast and even though the Venetian bronze-worker Alessandro Leopardi, who completed it, toned down some of its exuberance, it still overwhelms the visitor from its high pedestal. It outclasses the Donatello by its emotional power and was certainly the most famous equestrian statue of the Renaissance – even if the Venetians unscrupulously played down the Florentine Verrocchio’s achievement by giving the credit to their own Leopardi, whose name appears on the girth!

So when Forestiero preferred the horses of St Mark’s to the Marcus Aurelius and the Colleoni monument, he could hardly have paid them a greater compliment. Nevertheless, in one respect they might be considered inferior: in their display. As Veneziano had said, they were difficult to appreciate where they were – they were much too high up. A direct contrast could be made with the Marcus Aurelius, which Michelangelo deliberately planned to be the focal point of his Capitoline Hill. In 1561 it was set up in the centre of the square on a marble base, parts of which were taken from the nearby forum of the Emperor Trajan. As for the Colleoni monument, the tall pedestal on which it stood was the original work of Leopardi and was Roman in style. Its variegated sheets of marble were encased in columns and were embellished with tablets displaying trophies. It allowed Colleoni to be seen from all sides. Venetians were well aware of the limitations of the horses’ position. In 1558 Enea Vico suggested that they should be placed on a high pedestal like the one on which the Colleoni statue stood, but, unlike that statue, they should be placed in the square itself. He writes of ‘the noble quadriga of four extremely beautiful and undamaged horses, set over the main entrance to the temple of San Marco, a very rare work which both in art and all else is a very stupendous thing, and marvellous and perhaps the most beautiful in all Europe’. However,

The monument to Bartolomeo Colleoni in the Campo of SS. Giovanni e Paolo in Venice (1486) was an extraordinarily powerful sculpture which echoed the Marcus Aurelius, but many Venetians still preferred the horses of St Mark’s. (Campo S. Zanipolo, Venezia/Scala)

being against some large windows of dark glass, they are so greatly deprived of their viewpoint that they are not given that great consideration which such great art and such creations of beauty should merit. From which it seems to me that their dignity requires a very prominent high base of beautiful marble to be set between the flag-poles in the great Piazza [another creation of Leopardi’s still in place today], or at the other end of the Piazza opposite to the church [he means the Church of San Geminiano, which was to be demolished by Napoleon]; this might be so majestic and confining that it would be hard to see the feet of the horses, but unimpeded by the height of the pedestal, outlined against the sky, they would appear grander to the sight of onlookers.

Vico’s idea was greeted with some sympathy and, although it was never acted on, in the eighteenth century the painter Canaletto actually created a capriccio in which the horses are placed down in the square, as Vico had suggested, but in Canaletto’s version on separate pedestals.

In the sixteenth century, it was suggested that the horses should be placed on pedestals in the square so they could be better seen. It was never done, but in this capriccio by Canaletto (1697–1768) he imagines how they might have looked. (The Royal Collection © 2003, Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II)

It was, of course, possible to ‘display’ the horses by reproducing them in miniature. In the fifteenth century the ordinary collector was still able to pick up original antique statues. Jacopo Bellini is known to have had several and one, a Venus from Paphos in Cyprus, where Aphrodite was said to have been born in the sea, attributed to Praxiteles, was passed on to his son Gentile. It could be seen, by those interested, on a shelf in his studio in Venice. By the sixteenth century, however, only the wealthiest collector could afford original antiques and had to make do, as second best, with the work of contemporaries. Not that these were without quality. As Sabba di Castiglione (1485–1554) put it in a book of moral reflections published in Venice in 1546, ‘the Venetians decorate their houses with antiques, such as heads, torsos, busts, ancient marble or bronze statues. But since good ancient works, being scarce, cannot be obtained without the greatest difficulty, they decorate them with the works of Donatello or with the works of Michelangelo.’ The scarcity of originals led to a new market in small bronzes. Bronze always carried with it an aura of quality and antiquity, and a survey of the most common subjects shows that bronzes representing themes from classical mythology were more popular than those of Christian subjects. Animals or personifications of ideals, in particular, were much sought after. The major ‘Venetian’ centre for production in the late fifteenth century was Padua, though bronzes were also cast in Venice itself.

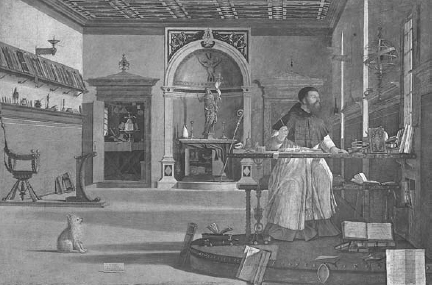

One of the attractions of small bronzes was that they could be kept for study or enjoyment in a domestic setting, and just such a setting is to be found in one of the most exquisite works of the Venetian artist Vittore Carpaccio, The Vision of St Augustine, painted at the very beginning of the sixteenth century as part of a cycle honouring the patron saints of the small confraternity or school of Dalmatian merchants and craftsmen living in Venice (the Schiavoni). St Augustine is shown in his study gazing out of his window towards a light which shines through it. In fact the saint being honoured in the painting was not Augustine, as might be imagined, but the austere and cantankerous Jerome, famous for his translation of the Bible into Latin. Carpaccio has depicted the legend that told of how, at the moment of Jerome’s death, just as Augustine was in the act of writing to him, a bright light flooded Augustine’s study and he realized that the great man was no longer on earth. The moment is cleverly dramatized not so much through the reaction of Augustine as through the little Maltese dog who sits on the floor transfixed by the light. It is said that Carpaccio modelled his Augustine on Cardinal Bessarion – formerly the archbishop of Nicaea – who had granted special indulgences to the confraternity and who, as noted earlier, had donated a great library of Greek manuscripts to Venice in 1468. The study is that of the quintessential Renaissance scholar. Books, music, astrolabes and an armillary sphere are neatly placed around the well-ordered room. Christian images, including a gilt bronze of Christ on the recess altar, alternate with pieces of Greek pottery and ancient spear-heads. There among them on the shelf is a small bronze of what seems to be one of the St Mark’s horses. This is not a fanciful suggestion, as it is known that bronze copies of them were made. One is now to be found in the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge, another in the National Museum in Munich and yet another in the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore.

In Carpaccio’s The Vision of St Augustine (early sixteenth century), a typical Renaissance interior is shown. On the shelf to the left, a model of one of the horses can be seen. Several of these bronze copies from the period survive. (Scuola di S. Giorgio degli Schiavoni, Venezia/Scala)

By the sixteenth century, then, the horses of St Mark’s seem to have worked themselves into the consciousness of many – artists, sculptors, ‘tourists’ in Venice and, of course, the Venetians themselves, to whom they were a matter of the greatest pride. The square that they overlooked had also been transformed. As already mentioned, in the 1490s a new clock tower, the Torre dell’Orologio, was built for the city. The site was an impressive one, on the northern side of the Piazza but directly facing the Piazzetta so that as the visitor landed he would see the large clock face fitting neatly at the end of his line of vision with the Campanile on one side and the Doge’s Palace and St Mark’s on the other. The site of the Torre was also an entrance point into the commercial part of the city, and so it acted to reinforce the separation of the Piazza as a distinct ceremonial area.

This late sixteenth-century view of the Piazzetta (by an unknown artist) shows the scene that would have greeted a visitor landing from the Bacino. Note how the southern façade of St Mark’s and the clock tower enhance the vista. Sansovino’s celebrated Library is in place on the left and his Loggetta, a meeting place for nobles before and after councils, can be seen at the foot of the Campanile. (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Beziers, France/Bridgeman Art Library)

The whole northern side of the Piazza alongside the Torre was given a facelift after the Procuratie Vecchie was damaged in 1514 in one of Venice’s many fires. The new building, completed in 1526, was in full Renaissance style, with three columned storeys, but characteristically is much lighter in tone than one would find in Italian cities on the mainland. On the bottom floor were shops, just as there are today, while the procurators let out the elegant apartments on the two higher floors to raise revenue for their building works. The procurators themselves were housed in a corresponding building on the south side of the Piazza, completed in the seventeenth century.

Further to enhance the grandeur of the area, three new buildings were commissioned by the Senate in the 1530s to fill the area on the west side of the Piazzetta. The first was a new state mint, the Zecca, on the shoreline itself. This was a strictly functional building. It had to keep all the gold and silver for the city’s coinage secure and also contain the furnaces which minted it. The architect was Jacopo Sansovino, a Florentine who came to Venice via Rome, where he had served his apprenticeship as sculptor and architect. In 1529 he was appointed the superintendent of all the building works for which the procurators were responsible. Having completed the Zecca he turned to his second commission, the most prestigious of the three: a grand new library to run in the space between the Zecca and the Piazzetta back to the Campanile. This building, in both style and function, marked the high point of the Venetian love affair with antiquity. It was constructed to house, as it still does, the library of Greek texts left to the city by Cardinal Bessarion in 1468. Yet at the same time it was a Roman building replete with allusions to the Roman past. It even had a room set aside for young nobles in which to learn how to read the classics in the original languages. Sansovino’s transformation of this area was completed by the Loggetta, a meeting place for nobles, built at the foot of the Campanile. All these buildings are happily intact, despite suffering some damage when the Campanile collapsed in 1902, and they provide a satisfying complement to the classical horses across the way on their loggia.

‘Our ancestors’, proclaimed the Venetian Senate in 1535,

have always striven and been vigilant so as to provide this city with most beautiful temples, private buildings and spacious squares, so that from a wild and uncultivated refuge … it has grown, been ornamented and constructed so as to become the most beautiful and illustrious city which at present exists in the world.

As always with the Venetians there was more than a touch of self-congratulation here, but by the sixteenth century the transformation of swamp and marshes into one of the grandest cities of Europe was complete. The horses were among its greatest treasures.