A republic famous, long powerful, remarkable for the singularity of its origin, of its site and institutions, has disappeared in our time, under our eyes, in a moment. Contemporary with the most ancient monarchies of Europe, isolated by its system and its position, it has perished in the great revolution that has overthrown many other states … Venice has disappeared with no possibility of returning; her people are effaced from the list of nations; and when, after the long storms, many of her ancient possessions will have regained her rights, the rich inheritance is no longer.

PIERRE DARU, History of the Venetian Republic,

1819 (trans. Margaret Plant)

FOR CENTURIES VENICE HAD BEEN PROTECTED BY A combination of its position as an island, its diplomacy and, often, sheer luck. With the city’s economic and political power almost gone, it could be tolerated by other Europeans as an aristocratic pleasure park. Yet even this limited role was placed in jeopardy when a new force hit northern Italy: the French Revolution as personified in the military genius of Napoleon Bonaparte.

The outbreak of the Revolution in 1789 had set off tremors across Europe, and in the first heady days of revolutionary fervour liberals everywhere supported its ideals. In Venice there were many, particularly among the impoverished nobility, the barnabotti (so called because they tended to congregate in the district round the Church of St Barnabas), and the bourgeois citizenry, who had always been excluded from power, who clamoured for change. Unsettled by the unrest, the doge and his ministers tightened up censorship and forbade public political meetings; as in France, the weight of centuries of tradition and introspection stifled any chance of effective reform. The Venetian government was unable to do more than react to events and its image was so steeped in aristocratic absolutism that when, in Paris, the royal palace of the Tuileries was stormed by a mob in August 1792 and the king could not at first be found, the crowd surged on to the house of the Venetian ambassador, suspecting he might have sheltered there.

By 1793 a coalition of conservative European powers – Britain, Austria, Prussia, Holland, Spain and Sardinia – was forming against the French, but Venice could not even muster the energy to join it. By now the city had little military strength – a poorly armed militia numbering perhaps no more than five thousand – but at least it might have derived some protection from membership of an alliance. Instead, it plunged deeper into isolation. Having already forfeited the opportunity of support from its neighbour Austria, Venice lost any chance of being regarded favourably by the new French regime when the brother of the guillotined king Louis XVI, the Comte de Lille, actually proclaimed himself the new king of France on Venetian territory in Verona. After protests from Paris the Venetians persuaded him to leave – but then found themselves in more trouble with the French when an Austrian army crossed the terraferma on the way to fight the French in central Italy. In a muddle typical of its diminished vitality, Venice claimed that Austria had the right to do so by an ancient treaty – then, when the French demanded to see the treaty document, could not find it.

In 1796 the French army in northern Italy was led by the 26-year-old general Napoleon Bonaparte, whose origins, in Corsica, were Italian.* In a series of startling victories that summer, Napoleon had seized Savoy and Lombardy and had reached the borders of Venice and Austria. Although he was technically the servant of the French government (at this point the Directory, which had come to power in November 1795), he was already assuming personal control of Italy’s destiny. As a child of the Revolution, he had absorbed the stories of Venice’s decadence and tyranny, and so was hardly predisposed to do the city any favours. The easiest way into the heartland of the Austrian empire was through the Brenner Pass, and Venetian envoys were bullied into allowing the French to occupy Verona, which stood at the foot of the pass. The retreating Austrian troops then tricked the Venetians into letting them occupy the fortress of Peschiera on the edge of Lake Garda to the north of Verona, which simply gave Napoleon another excuse for vilifying Venice. Belatedly the Venetians began raising a new militia on the terraferma, but the recruits were so ill-disciplined they soon became involved in scraps with the French occupying troops. When riots broke out in Verona Napoleon took his chance to send an envoy to Venice to tell the doge and the Collegio that if the Venetians did not bring the militia to order he would declare war on Venice. The Senate offered a cringing apology but it was rendered meaningless when a full-scale revolt broke out in Verona. It was suppressed in April 1797, after which the city was stripped of its art treasures and required to provide horses, boots and cloth for the French armies.

The French occupying forces in northern Italy claimed that they were liberators, but this meant little to the conservative Italian peasantry. Unrest simmered. By early 1797 Napoleon had crossed into Austria and realized that he risked being isolated on the far side of the Alps if he did not impose a political solution that would secure his rear. In a secret treaty with the Austrians made in April 1797 he forced them to surrender central Italy, telling them that they could have the Venetian terraferma in compensation. Having made the deal and now needing to impose it, he had fresh incentive for humiliating Venice. He rested his case on the ‘tyranny’ of the Venetian government. ‘I will have no more Inquisition, no more Senate. I shall be an Attila to the state of Venice,’ he told a grovelling set of Venetian envoys who had caught up with him in Austria. Just as the envoys were setting off back to Venice, messengers from the city arrived with ominous news. On 20 April a French lugger, the Libérateur, had entered the lagoon, and even though no actual state of war existed between Venice and France, it had been treated as an enemy ship and fired upon; its commander had been killed. The unfortunate envoys were told to return to Napoleon to present a Venetian version of events. It was hardly convincing and Napoleon exploited his opportunity. The murder of the Libérateur’s commander, he blustered, was ‘without parallel in the annals of the nations of our time’, and he considered himself fully justified in declaring war.

In the last days of April 1797 French troops reached the shores of the lagoon and began training their guns on Venice. An ultimatum arrived asking for a complete capitulation of the city. Three thousand French troops were to be allowed to enter to take over all strategic buildings and the French would assume command over what remained of the Venetian fleet. A democratic government was to be installed and all political prisoners were to be released. (French propagandists had long talked of torture chambers deep in the Doge’s Palace.) Twenty paintings and six hundred manuscripts, to be chosen by French commissioners, were to be handed over to the French.

The Venetian government had allowed itself to be outmanoeuvred and was now completely exposed. Even so, it might have faced the challenge with more dignity. A meeting of the Grand Council was called for 12 May, but so many members of the nobility had fled to the mainland or failed to turn up on the day that it did not even have the required quorum of six hundred. There was little will to resist. The doge moved that the Council should surrender its powers to a democratic government in the hope, he argued, of ‘preserving the religion, life and property of all these most beloved inhabitants’. The resolution received the support of 512 of the 537 nobles who had appeared – many of whom, as soon as they had voted, slipped off their robes and left by back entrances of the palace, perhaps hoping to avoid the bands of more resolute citizens who were touring the streets chanting ‘Viva San Marco!’ Back in the palace, Ludovico Manin, the 118th of the doges, faced an almost empty Council Chamber and declared the resolution carried. Returning to his quarters he handed his corno and linen cap to his manservant. ‘Take these,’ he said, in a final tired gesture of abdication, ‘I shall not be needing them again’.

The republic had collapsed with no more than a whimper, the victim of its own moral and political bankruptcy. On 12 May ‘there died’, wrote Ippolito Nievo in Confessioni d’un Italiano, his novel of the downfall of the republic published in 1858, ‘a great queen of fourteen centuries, without tears, without dignity, without funeral’. Venice had, of course, surrendered itself to the bullying of Napoleon; but the fiction was promulgated that the city had been ‘liberated’ from tyranny. Within a few days ‘Year One of Italian Liberty’ had been proclaimed and a Committee of Public Instruction set up under French supervision to educate the Venetians in their new life. The history of Venice, so carefully manipulated by its rulers in the past, now received a radical makeover. Originally, it was now said, the Venetians had fled to the lagoon in order to live in liberty; then, with the law of the Serrata of 1297, instituting closed rule by the nobility, this had all been lost. It was fitting that exactly five hundred years later the original liberty of its citizens should be restored. To provide a symbolic marker of the occasion the remains of the doge responsible for the Serrata, Pietro Gradenigo, were exhumed from the Church of San Cipriano and thrown to the winds.

The new freedom was to be celebrated on 4 June with a festival in the Piazza San Marco, which, in a moment of anti-clerical fervour, was renamed (somewhat prosaically) Piazza Grande. A Tree of Liberty was set up in the Piazza and placards with slogans were erected proclaiming ‘Established liberty brings about universal peace’ and ‘Dawning liberty is protected by force of arms’ – the latter a reference to the French garrison which now kept order in the city. On the day of the festival itself, bands marched round the Piazza with processions of citizens in tow. The newly appointed president of ‘the sovereign people of Venice’, one Angelo Talier, extolled the Tree of Liberty as a symbol of regeneration. ‘The day destined for the erection of the sacred Tree of Liberty will be a day of joy for all true citizens, who may begin to live the worthy life of man, and it will be a monument of gratitude to our descendants, who will bless the generosity of France.’ (Whatever noble ideals the French revolutionaries held, they did not include equality of the sexes. It was argued that the ‘feminine’ softness of aristocratic vanity and luxury had been transformed into the more ‘manly’ valour of ‘democratic industry’!) So the myth was sustained that the French had simply enabled an organic revolution of the Venetian masses (‘Long live the heroes of France, lightnings of war, who without shedding a drop of blood among us, knew how to break our harsh bonds’), and the president’s speech led on to a symbolic burning of the Golden Book, in which the names of the noble families were recorded, together with the corno and other insignia of the doges. Suitable exhortations on ‘the hateful and detestable aristocratic yoke’ accompanied their reduction to ashes. The Fenice, the opera house, was ordered to put on relevant shows inspired by glorious moments of the Roman republican past, notably a drama of the assassination of Caesar by Brutus.

Few of those watching the ‘celebrations’ can have been deceived. The Venetian playwright Carlo Gozzi saw the dance around the Tree of Liberty as a Dance of Death.

The sweet delusive dream of a democracy … made men howl and laugh and dance and weep together. The ululations of the dreamers, yelling out Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, deafened our ears, and those of us who still remained awake were forced to feign ourselves dreamers, in order to protect their honour, their property, their lives.

The reality of the refound Venetian ‘liberty’ was soon exposed. The only real liberation was that of the Jews, whose ghetto (the word, which is believed to have been derived from a medieval Venetian word for foundry, is first recorded in Venice) was opened up and its gates burned so that its inhabitants were no longer segregated. There was never a democratic election in the city, and in the Treaty of Campo Formio made between Napoleon and Austria in October 1797, Venice and the Dalmatian coast were simply handed over to Austria.

Before the new owners arrived, Napoleon, who was to visit Venice only once, for ten days in 1807, put in hand the city’s final humiliation. The Bucintoro, the state barge, was burned and the commissioners arrived to select the paintings and manuscripts according to the ultimatum announced by Napoleon in May. In the spirit of the Revolution, the church and the seat of autocratic government were to bear the brunt of the confiscations. So the ceilings of the Council of Ten’s meeting room and the refectory of the monastery of San Giorgio Maggiore were stripped of their Veroneses, and a selection of Titians and Tintorettos, together with a stunning Giovanni Bellini, The Madonna and Child Enthroned from the Church of San Zaccaria, were collected. The commissioners confined themselves to their original quota of twenty paintings; such was the mass of riches available they even passed over the two great Titian altarpieces of the Frari, taking instead another Titian from Santi Giovanni e Paolo, The Death of St Peter Martyr, which was then considered his masterpiece.*

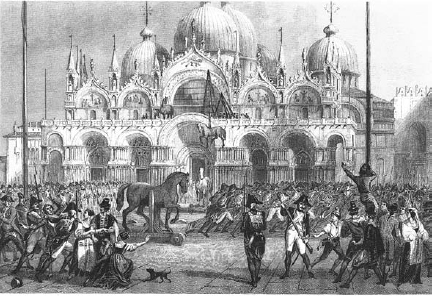

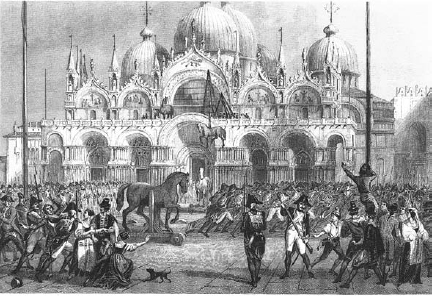

No sculpture had been mentioned in the ultimatum and it was only after the commissioners left, on 13 December, that the four horses were lowered from their platform on the loggia of St Mark’s on to carts to be transported to Paris. It has to be assumed that Napoleon himself insisted on their addition to the haul. He had already ordered any lions of Venice to be destroyed as symbols of the old regime, although the winged lion on the column in the Piazzetta was among those saved and taken to France. (It was re-erected on a fountain in front of the Hôpital des Invalides in Paris, having suffered the indignity of having its proudly outstretched tail cut off and replaced between its legs.) As for the horses, a surviving French print shows the massed French troops alongside the Piazza, with one horse already being drawn away as the last still dangles down from a rope over the portico. The watching crowd stands silent. Another, perhaps more accurate in that the horses are being hauled by soldiers towards the water rather than away from it as in the first, shows protesting Venetian citizens being roughly treated by the French troops. It seems to have been a richly remembered moment, and as late as 1839 a play called The Horses of the Carrousel: The Last Day of Venice was performed in Paris. Napoleon himself makes a guest appearance to the sound of the ‘Marseillaise’ and orders the horses off to ‘the Carrousel’, their new home in Paris.*

The horses are removed from St Mark’s on the orders of Napoleon in December 1797. Protesting Venetians are roughly dealt with by the French troops. (Charles Freeman)

The Venetians’ anger at the French was such that the arrival of their new overlords the Austrians – aristocratic, Catholic and ready to respect the Venetian heritage – in early 1798 was greeted with some relief. The great Venetian sculptor Antonio Canova wrote from his home village of Possagno on the mainland: ‘I do not have to strain my imagination to believe the joy of all the Venetian population and that of the Terra Firma at the arrival of the Austrian troops; peace, tranquillity, security are real benefits not to be compared with the fantasies of hotheads.’ Yet the horses were gone.

It was Canova who was eventually to secure their return.