Before St Mark still glow his steeds of brass,

Their gilded collars glittering in the sun;

But is not Doria’s menace come to pass?

Are they not bridled? Venice, lost and won,

Her thirteen hundred years of freedom done,

Sinks like a seaweed, into whence she rose!

Better be whelm’d beneath the waves, and shun,

Even in destruction’s depth, her foreign foes,

From whom submission wrings an infamous repose.

BYRON, Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage,

canto IV, xiii

THE HORSES RETURNED TO VENICE BY LAND, AND IT SEEMS to have been a rough journey. At some point the decoration which had covered their collars, and which can be seen clearly in the engravings of the Zanetti cousins, was lost. It would have been all too easy for souvenir seekers to have prised it off – it may even have been removed in Paris. More dramatically, there are reports that the horses’ heads became detached (they had been cast separately and the join to the bodies concealed by the collars) and so it was that when they arrived in Venice on 7 December, having crossed the lagoon on a raft, they were taken to the Arsenale for repair. As we have seen, Canova had been asked by the Austrian emperor where they should be placed; he had suggested that they might stand two either side of the main entrance to the Doge’s Palace on the waterfront, gazing in fact straight across at Palladio’s Church of San Giorgio. He was opposed by the president of the Venetian Academy, Count Leopoldo Cicognara, who insisted that, as an ancient symbol of Venice’s pride, they be put back on St Mark’s. Francis, anxious to avoid upsetting Venetian opinion, acquiesced.

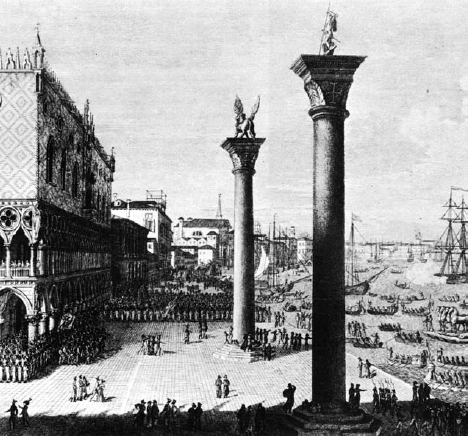

On 13 December 1815 the Austrian governor of the Venetian provinces, Count Peter von Goess, officially handed the horses, still in the Arsenale, over to the mayor of Venice. The emperor was present, together with his chancellor, Prince Metternich, and his role was commemorated in an engraving in which Francis is presented as a classical hero: nude but with a robe hanging loosely from his arms over his body, he stands on a sea shell which floats in front of the Doge’s Palace and the Campanile, with the four horses, plumed and delicately posed, beside him. The theme is that of an apotheosis, the translation of a hero to heaven, a scene well known in classical art with the hero normally ascending upwards in a quadriga. It seems an appropriate way to have honoured Francis in this era of enthusiasm for classicism. In reality, the horses came round the eastern end of Venice on a raft on which the standards of Austria and Venice were displayed. A 21-gun salute heralded their departure from the Arsenale in the north of the city, massed troops awaited their arrival at the Piazzetta. They were then pulled along the Piazzetta towards St Mark’s between ranks of soldiers and hauled into place to the accompaniment of musket shots and cannon fire. An oil painting of the event, formally commissioned by Metternich from Vincenzo Chilone, one of Canaletto’s pupils, shows the horses waiting by the portal of St Mark’s for their elevation back on to the loggia.

Canova was not in Venice to witness the horses’ return. He had gone straight on to London from Paris and stayed there until the first week of December. By early January 1816, however, he was in Rome to see the Vatican collection arrive safely home – after all, he was officially responsible to the pope for its rescue – and here he was created marquess of Ischia in recognition of his achievement. The occasion marked the end of a tumultuous six months. Following his diplomatic successes in Paris, he had been fêted in London: he had been honoured at a dinner at the Royal Academy, received by the Prince Regent (who slipped him £500 in a gold snuff box) and subjected to a whirl of social engagements and meetings with the leading British sculptors of the day. One of the highlights of his visit was his viewing of the Elgin marbles. Traditionally they had been credited to Phidias, or at least to a workshop acting under his control, and this bathed them in an aura of quality. In 1803 Elgin had taken drawings of his acquisitions to Rome specifically to show Canova, much of whose work was inextricably linked to classical models, and Canova had urged that they be left unrestored so that their original quality could be seen: ‘It would be a sacrilege to touch them with a chisel.’ It was an important moment in the history of taste. In the eighteenth century there had been a passion for restoration and many ancient sculptures had had spare arms and legs fitted to them to make them ‘whole’. Now damaged sculptures acquired a romantic cachet, and the Elgin marbles were never added to.*

Francis restores the horses to Venice, which awaits their return as the sun rises behind the clock tower. A watercolour of 1815. In fact, the restoration went hand in hand with the economic collapse of the city. (Museo Correr/Venezia)

After repairs in the Arsenale, the horses were taken round the eastern end of Venice by barge so that they could be ceremoniously welcomed at the Piazzetta. They arrived on 13 December 1815, eighteen years to the day after they had been removed. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

The horses arrive at St Mark’s before being restored to their place on the loggia. Oil painting by Vincenzo Chilone. (The Art Archive)

The marbles had arrived in London in fragments between 1802 and 1812, although it was not until 1806 that the British public started to become aware of the importance of the collection. Installed first at a Park Lane mansion leased by Lord Elgin, they were then transferred to a shed at the back of Burlington House on Piccadilly, where it was possible to apply to view them. By the time Canova had arrived in London the marbles were well known, and there were impassioned debates over whether they should be bought from Lord Elgin for the nation. As the first major set of sculptures from the fifth century BC to be seen in western Europe, they were hard to assess against the well-known but much later favourites of the Roman collections. Some even doubted their age – a Mr Payne Knight, for instance, a prominent member of the Society of Dilettanti, insisted that they were Roman work from the time of Hadrian and of little interest. As the view of an adviser to many aristocratic collectors of antiquities, his judgements carried weight and he clung to them with determination, even suggesting at one point that the quality of the metopes, the panels which ran along the entablature above the columns, was so low that those who had carved them did not even deserve to be called artists. Most artists of the day, on the other hand, were bowled over by them, impressed by their simplicity and liveliness and above all their truth to nature. It had long been assumed, as in the Platonic tradition, that the ‘ideal’ statue of a human figure should be somehow more perfect than an actual human, just as Zeuxis’ painting of an ideal woman described in Pliny’s Natural History was composed of the finest points of five nude models. Yet here were sculptures which seemed to have been created directly from live models. (At one point two boxers were brought in to stand naked before them to make the point.) Instead of the bodies being beautifully proportioned, the muscles bulged according to the stress placed on them, sometimes on one side of the body only. The skin even contained veins, something that the ‘idealists’ had always said was incompatible with the ‘noble grandeur’ that Winckelmann had prescribed for this period of art. For those willing to look afresh at classical art they were a revelation.

When William Hamilton invited his friend Canova to come and see the sculptures in their temporary resting place at Burlington House, Canova can hardly have needed much persuading; but he was probably unaware of the extent to which he would be used in the campaign to have them bought by the British government. Elgin had spent many thousands of pounds on transporting the marbles to England and the first offers from the government fell far below his expenses. The campaign to sell them had become embroiled in other complications. The influential Payne Knight continued to deny their importance, while the poet Byron, who was imbued with a love of Greece and a passionate commitment to its independence, virulently attacked Elgin for removing the marbles at all (he had actually been in Athens when Lord Elgin’s agents were removing the metopes and he claimed that their clumsiness had led to some being damaged), even though at first his own opinion of the marbles as a whole was no higher than Payne Knight’s. The end of the war, moreover, had brought an economic slump and there were others who pointed out the inequity of buying ancient sculptures when so many were starving.

In the event Canova helped break the deadlock by announcing that the marbles were superior to the statues of the Vatican which he had just saved, and that they had opened his eyes to the skills of the ancients before these had been debased by the desire of later generations for ‘conventional and mathematical symmetry’. ‘Everything here breathes life, with a veracity, with a knowledge for art which is the more exquisite for being without the least ostentation and parade of it, which is concealed by consummate and masterly skill.’ It had been worth coming to London, he told Lord Elgin, simply for the purpose of seeing them. A rival frieze which had also arrived in London, taken from the temple of Bassae in the Peloponnese and dating from the later fifth century, a generation after the Parthenon, had been bought by the British government at auction for £15,000. In that case, said Canova, the Elgin marbles are worth £100,000. His remarks were quoted by virtually every witness who appeared before the parliamentary select committee which was considering the purchase. Eventually it was agreed to buy them for the nation for £35,000, and this sum was accepted by Elgin even though it was well below what he had spent on shipping and displaying them.

As we have seen, as early as the fifteenth century the Venetian horses had been attributed to Phidias, and it was inevitable that comparisons would be made between the Parthenon reliefs and the horses. It was perhaps unfortunate that the issue was taken up by the painter Benjamin Haydon. Haydon, later well known as a painter of history scenes, had arrived in London in 1804 to study at the Royal Academy. He was only eighteen at the time, an unsettled young man, but totally convinced of his own genius. He was furious when in 1806 (he was still only twenty) his entry in the Academy’s annual exhibition was placed in a side room of Somerset House rather than being exhibited in the most prestigious gallery. The fact that it had been selected at all failed to calm the antagonism between him and the Academicians which smouldered for the rest of his life. In 1808 he visited the marbles and, as he wrote later in his autobiography, was overwhelmed by them. ‘I felt as if a divine truth had blazed inwardly upon my mind and I knew that they would at last rouse the art of Europe from its slumber in the darkness.’ Like others, he was enthralled by their truth to nature and he became obsessed by the details of the human bodies, spending hours in Burlington House copying wrists and feet. One feature which inspired him particularly was the head belonging to a horse from the quadriga of the moon-goddess, Selene, which ‘overflowed’ from the end of the eastern pediment. Writing to Elgin in February 1809, he enthused: ‘that horse’s head is the highest effort of human conception and execution; if the greatest artist the world ever saw did not execute them [the marbles as a whole] I know not who did – look at the eye, the nostril, and the mouth, it is enough to breathe fire into the marble around it.’

Like every artist and connoisseur brought up on the superiority of the Vatican figures, Haydon was presented with the dilemma of relating the Parthenon sculptures to them. Over the next few months he gradually came to revise his view of the Apollo Belvedere, which he had followed Winckelmann and conventional opinion in applauding. By 1816 it had become to him no more than a work from late antiquity, a period ‘when great principles had given way to minute and trifling elegances, the characteristics of all periods of decay’. As was typical with Haydon, the exaltation of one work of art required the denigration of another, and it was now that the Venetian horses came to be caught in his sights. He had seen a cast of one of them, and in an article in the Annals of Fine Arts for 1819 reproduced a drawing he had made of it alongside the Parthenon horse which so excited him. Having assumed that the horses of St Mark’s were by Lysippus, in other words a mere hundred years later than the Parthenon, he lamented how ‘the great principles of nature could have been so nearly lost in the time between Pheidias and Lysippus’. He then launched into a diatribe. The great crime of the Venetian horses was that they were not true to life. No horse, says Haydon, could have sunken eyes as they did, because it would not have been able to see danger. The eyes of the Parthenon horse are alert to what is around them; those of the Venetian horses are not. The nostrils ‘of the Venetian horses seem wrongly placed, the upper lip does not project enough and there is an evident grin as it if had the snarling muscles of a carnivorous animal … it looks swollen and puffed as if it had the dropsy.’ How could Raphael and other painters who were inspired by the horses possibly think that by copying them they were emulating nature, ‘the great source of all beauty and truth’? Haydon was, of course, turning his back on the Platonic tradition and returning to one which saw nature, rather than idealized versions of it, as the source of inspiration for great art.

Benjamin Haydon placed the head of the horse from the Parthenon pediment (left) alongside one of the horses of St Mark’s in order to denigrate the latter (1819). (Charles Freeman)

The head of one of the horses drawing the chariot of the moon-goddess Selene, from the eastern pediment of the Parthenon, 430s BC. This was the head idealized by Haydon (see previous page). (Ancient Art & Architecture Collection)

Haydon took his campaign to Europe. His article in the Annals of Fine Arts was translated as ‘Comparaison entre la tête d’un des Chevaux de Venise et la tête du Cheval d’Elgin du Parthénon’, and in this form it came to the attention of Goethe. At first Goethe, who as we have seen had examined the horses at close quarters on his visits to Venice twenty-five years before, rejected Haydon’s denigration as unjust. Then he saw a cast of the Parthenon horse and had to acknowledge that it was the equal of those in Venice (he had his own cast of one of the horses’ heads to compare it with). On the other hand, he refused to make a comparison of quality. While accepting that ‘the artist [of the Parthenon] had created the original ideal of the horse … among intelligent people there could be no question that through both of these works we are presented with a new conception of nature and art.’ He echoed the comments of others when he argued that comparisons with an ideal and comparisons with truth to nature were equally valid ways of assessing the quality of a work of art. Such an approach had its advantages in that it enabled those who had been conditioned to see the Apollo Belvedere and its companions as the high point of ancient art to keep their enthusiasm intact while remaining receptive to the Parthenon sculptures. The two groups of works represented the pinnacles of two different kinds of art. However, from now on the Apollo Belvedere began to fall from favour. It was acknowledged as a copy of something earlier, perhaps not even a good one at that, and unable to stand comparison with the original work of so many centuries before.

Haydon’s attack, then, failed to win wider support, but in Venice a fresh battle was breaking out over the origins of the horses, one which reflected wider debates over the classical past in a Europe now caught up in the throes of nationalism and romanticism. In an earlier chapter it was noted that Venice had been happy to draw on the pasts of both Greece and Rome, but by the early nineteenth century the debate over the rival merits of the two cultures reached a new intensity. It is a Venetian, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, who deserves the credit for reviving interest in the architectural achievements of Rome. Born in Venice in 1720, the son of a stonemason, Piranesi absorbed Roman history as a boy and by 1740 he was on his way to Rome ‘to admire and learn from those august relics which still remain of Roman majesty and magnificence, the most perfect there is of Architecture’. His famous Vedute (scenes) of Rome, his Capricci, made up of imagined Roman buildings, and his meticulous measurement and drawing of surviving Roman buildings gave him an international reputation, enhanced by the ease with which his prints (of which there were eventually over a thousand) could be bought in Rome and taken home by travellers on the Grand Tour. Goethe’s first views of Rome had been through Piranesi’s prints, and their impact was such that he was disappointed to find that Roman buildings appeared much smaller than he had imagined from Piranesi’s grandiose reconstructions.

Crucially, Piranesi became the champion of ancient Rome against Greece. When challenged by travellers who had visited Athens and who maintained that Greek architecture was superior to Roman, Piranesi replied that Roman architecture was much more creative and richer in variety, and had a magnificence in its conception which the Greeks could not match. One only had to look at the range of Roman buildings, from aqueducts to bath houses, amphitheatres to sewer systems, he said, to see the point. Understandably, Piranesi was furious with Winckelmann for championing the Greeks so exclusively. ‘Must the genius of our artists be so basely enslaved to the Grecian manners, as not to dare to take what is beautiful from elsewhere, if it not be of Grecian origin?’ he inveighed. There was also much to be found, he argued, in Egyptian and Etruscan art; in one of his more outrageous and unbalanced judgements, Piranesi went so far as to suggest that the Greeks themselves had borrowed from Etruscan art and then debased it!

By the time Piranesi died in Rome in 1778 he had established that Roman architecture had to be taken seriously and that Greece was not necessarily the canon by which taste should be set. His prints had their impact. All over Europe and even in America Roman-style buildings appeared (the dome and the arch are the most common pointers to a Roman inspiration). His achievement merged into the revived sense of Italian nationalism which was animated by the plunderings of Napoleon. As we have seen, Napoleon’s legacy was an ambiguous one in that he destroyed elements of the Roman past by removing so many original works of art from their Italian settings, but he also recreated Roman ideals of imperial power in his capital. This clash between destruction of the Roman past and ‘classical’ rebuilding could be seen in Venice itself. In an attempt to create an imperial palace in the city, Napoleon ordered the demolition of the west side of the Piazza San Marco, including Sansovino’s Church of San Geminiano, so that the Procuratie Nuove, on the south side of the Piazza, could be extended round the Piazza and have a ballroom included in it. Thus on their return the horses found themselves looking down the Piazza towards a neoclassical building, one which, it has to be admitted, was not totally out of harmony with the rest of the square. (Its bays echo those of Sansovino’s Library.) The height of the ballroom required the new building to be vaulted, and the vault itself was faced on the side overlooking St Mark’s with, appropriately enough, statues of Roman emperors.

The ‘Roman is best’ theme was also developed by the director of the Venetian Academy, Count Leopoldo Cicognara. Cicognara, an Italian aristocrat born in 1767 in Ferrara, devoted his early life to art and good living, but he was a man of the Enlightenment and his political sympathies were liberal. He had supported the ideals of the French Revolution, at least until the moment when Louis XVI was executed. Even then, his attachment to France revived and persisted long enough for him to welcome the French revolutionary armies to Italy. He even dedicated a treatise, Il Bello, ‘The Beautiful’, to Napoleon himself. In 1808, with Venice now part of Napoleon’s kingdom of Italy, he was made president of the Venetian Academy, and he lived out the rest of his life in the city. It was he who insisted that the horses be returned to the loggia on their return, rather than being placed by the waterfront as Canova had suggested.

In the years preceding Napoleon’s overthrow Cicognara had embarked on a major history of sculpture, one in which he tried to place styles and achievements within the context of political events. An important influence on his view of classical history was Edward Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in which the English historian had argued that the adoption of Christianity had brought about the fall of the empire. Gibbon had said little about art, but Cicognara linked the decline in classical art, as Gibbon had linked the decay of the empire to ‘the triumph of barbarism and religion’. Christians, he argued, had always hated fine art and it was they, not the Goths, who had been responsible for destroying it as the empire collapsed in the fifth century AD. Had not Pope Gregory the Great ordered that all pagan art be thrown in the Tiber? (It is now known that this story was a much later fabrication; Gregory, a Roman aristocrat, tended to be more moderate in such matters.) Was not the sack of Rome by the Christian Emperor Charles V in 1527 far more destructive than the sack by the Goths? (This was a deliberately provocative point but one which contained some truth in that the Goths’ ‘sack’ of Rome in 410 had been comparatively restrained.)

Implicit in Cicognara’s argument was the assumption that Roman art did not contain the seeds of its own decay and that it deserved recognition in its own right, a view which supported Piranesi’s interpretation. Cicognara valued the horses of St Mark’s precisely because, as he argued, they were Roman art. In a treatise on the horses published in Venice in 1815 he perpetuated the idea that they came from the time of Nero, but backed it with evidence that went beyond mere tradition. He argued that the almost pure copper of which the horses were made, together with their gilding, argued for a date in the early centuries AD, while what he saw as their ‘heavy’ style suggested Italian rather than eastern models. The most likely setting for a quadriga in this period was a Roman triumphal arch. This and the evidence of Tacitus, he argued, combined to make the reign of Nero the most likely date for their manufacture.

The argument that the horses were of Roman origin was also put forward in another pamphlet, issued in 1817 by one Count Girolamo Andrea Dandolo, a youthful descendant of the family responsible for their seizure. Dandolo claimed that these were chariot horses, had been on Nero’s triumphal arch and had then been taken to Constantinople. He identified the chariot with that mentioned in the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai as bearing a sun-god and standing in the Milion in the city. The head of Nero (the original charioteer) had, said Dandolo, been taken off and replaced with one of the sun-god.

These views were soon challenged. When the horses had been in Paris, the consensus among the French connoisseurs had been that they were Greek. One Joseph Leitz argued from the style of their manes that they were by either the sculptor Myron or Polyclitus, the master of proportion. Myron, who came from Eleutherae, on the border between the Attic plain and Boeotia, in central Greece, was active between 470 and 440 BC, and thus has the honour of being the earliest sculptor to whom the horses have been attributed. Copies of several of his sculptures, notably his discus thrower, survive, but there is nothing in his work which can convincingly link him to the horses (although it is known that ‘animals’ were among the pieces he produced). Leitz’s attribution seems to be another case of the horses being linked to a prominent name on the assumption that they ‘deserved’ a great sculptor. A Greek origin (Lysippus again) was supported by a M. de Choiseul-Daillecourt in 1809, and a different one – the horses from Chios mentioned in the Parastaseis Syntomoi Chronikai as the set brought to Constantinople – by a M. Sobry in 1810.

So Cicognara’s assertion in his treatise of 1815 that the horses originated in Rome was bound to excite a reaction from the ‘Greek’ supporters; and it came, in 1816, in the shape of a pamphlet by a German enthusiast for Greece, August Wilhelm von Schlegel (1767–1845). Schlegel was a polymath, a translator of Shakespeare (he managed to complete translations of seventeen of the plays), the founder of Sanskrit studies in Germany and, with his younger brother Friedrich, a spearhead of a German national Romanticism which found its roots in ancient Greece. Winckelmann, of course, wrote in German, and the erotic intensity of his writings had gained him a wide readership among intellectuals, including Goethe. So the ‘superiority’ of the Greeks over ‘the decadent Romans’ became part of the received wisdom of Germany’s cultural elite, a principle embedded in German intellectual life. It gained particular force as a model for German renewal after the traumatic defeat of Prussia, the largest of the German states, by Napoleon at the battles of Jena and Auerstadt. The inspirational figure here was Wilhelm von Humboldt, a nobleman from Brandenburg who was briefly head of the education section of the ministry of the interior and founder in 1810 of the University of Berlin. Humboldt believed a spiritual transformation was essential if Prussian confidence were to be restored and that it was to be found in the ancient Greeks. Not only did the commitment of the Greeks to their cities provide the model for civic involvement, but their culture was infused with the finest art and poetry. In Greece man had been ennobled by his religion – not humiliated, as in Christianity – and Greek thinkers had established the foundations of ethics. In short, Greece provided everything that was needed for revival. Through a study of ancient Greek (which Humboldt made central to the curriculum and compulsory for those wishing to enter university), this great culture could be explored and absorbed.

It was hardly surprising, then, that a leading German intellectual such as Schlegel would be determined to claim the horses for the Greeks; but this was more than a romantic assertion. Schlegel attacked Cicognara’s treatise systematically. He pointed out, rightly, that the Greeks also created sculptures of quadrigae as commemorations of their successes in the games. There had been one, for instance, on the Acropolis in Athens. With less supporting evidence, he argued that the Greeks gilded their statues and copied different breeds of horses, so that one could not identify art as Roman simply because it depicted ‘heavy’ horses. As for an actual sculptor, he opted for Lysippus, as Haydon had done, thus placing the horses in the Greek world of the fourth century BC. He even suggested that they might be a victory monument from the Olympic Games.

For all the arguments back and forth, the problem remained that the horses were simply not datable on the evidence that existed at the time. Their creation was still being attributed to sculptors from the fifth century BC to the first century AD. Comparisons of style and literary texts were being used freely in support of widely varying conclusions, all advanced with far more conviction than the evidence allowed. Nor were the arguments confined to the aesthetic; in both Germany and Italy, powerful nationalist forces acted to shape and prejudice the debate.

In Venice the growing strength of Italian nationalism became evident in 1822 when Canova died, probably of stomach cancer, in a room overlooking the Piazza San Marco. It fell to Cicognara, a staunch admirer and friend of the great sculptor, to preside over the funeral arrangements. Cicognara had kept his post as president of the Venetian Academy under the Austrian rulers, but his known anti-clerical feelings and his championing of Italian nationalism had made the authorities deeply suspicious of him. Canova’s own position was less clear – he had been more receptive to the Austrians, who had supported his campaign for the restoration of Venice’s treasures, and he was more sympathetic to Catholicism – but among the people as a whole he was seen as representing the forces of Italian nationalism. The Austrian authorities in Venice were caught in a dilemma. They could hardly deny Canova a fine funeral, but they feared popular unrest. So strict rules about how the ceremony should be conducted were laid down. No one could wear black, the colour associated with the carbonari (literally, ‘the charcoal burners’), the revolutionary associations which campaigned for the expulsion of Italy’s foreign rulers, and an exact funeral route was specified.

But the nationalists were not to be thwarted. Cicognara and his supporters turned out in green, the colour of the royal house of Savoy, which was seen as a focus for Italian unity. The funeral was held in St Mark’s – nowhere else was fitting – but Cicognara managed to circumvent the instructions about the route of the funeral procession and had the coffin brought into the Academy, where he made an impassioned speech over it. (Canova’s heart was later enshrined in the Academy and is now buried in the Church of Santa Maria dei Frari; the rest of him went home to Possagno, to lie in a massive neoclassical temple he had designed himself.) An outpouring of sonnets and pamphlets lamenting Canova’s death showed how deeply he had penetrated the Italian consciousness, and his monument to Alfieri in Florence became a patriotic shrine. ‘May these precious names, so dear to the fatherland of Alfieri and Canova, united for ever and respected by Time the destroyer, uphold and witness to remote posterity the glory and splendour of Italy,’ wrote one admirer. No wonder, then, that the nationalists insisted that the horses, saved as they had been from the French, were Italian in origin.