Updated by Will Tizard

Full of fairy-tale vistas, Prague is beautiful in a way that makes even the most jaded traveler stop and snap pictures. The city is physically divided in two by the Vltava River (also sometimes known by its German name, the Moldau), which runs from south to north with a single sharp turn to the east.

Originally, Prague was composed of five independent towns: Hradčany (the Castle Area), Malá Strana (Lesser Quarter), Staré Město (Old Town), Nové Město (New Town), and Josefov (Jewish Quarter), and these areas still make up the heart of Prague—what you think of when picturing its famed winding cobblestone streets and squares.

Hradčany, the seat of Czech royalty for hundreds of years, centers on the Pražský hrad (Prague Castle)—itself the site of the president’s office. A cluster of white buildings yoked around the pointed steeples of a chapel, Prague Castle overlooks the city from a hilltop west of the Vltava River. Steps lead down from Hradčany to the Lesser Quarter, an area dense with ornate mansions built for the 17th- and 18th-century nobility.

The looming Karlův most (Charles Bridge) connects the Lesser Quarter with the Old Town. Old Town is hemmed in by the curving Vltava and three large commercial avenues: Revoluční to the east, Na příkopě to the southeast, and Národní třída to the south. A few blocks east of the bridge is the district’s focal point: Staroměstské náměstí (Old Town Square), a former medieval marketplace laced with pastel-color baroque houses—easily one of the most beautiful central squares in Europe. To the north of Old Town Square the diminutive Jewish Quarter fans out around a tony avenue called Pařížská.

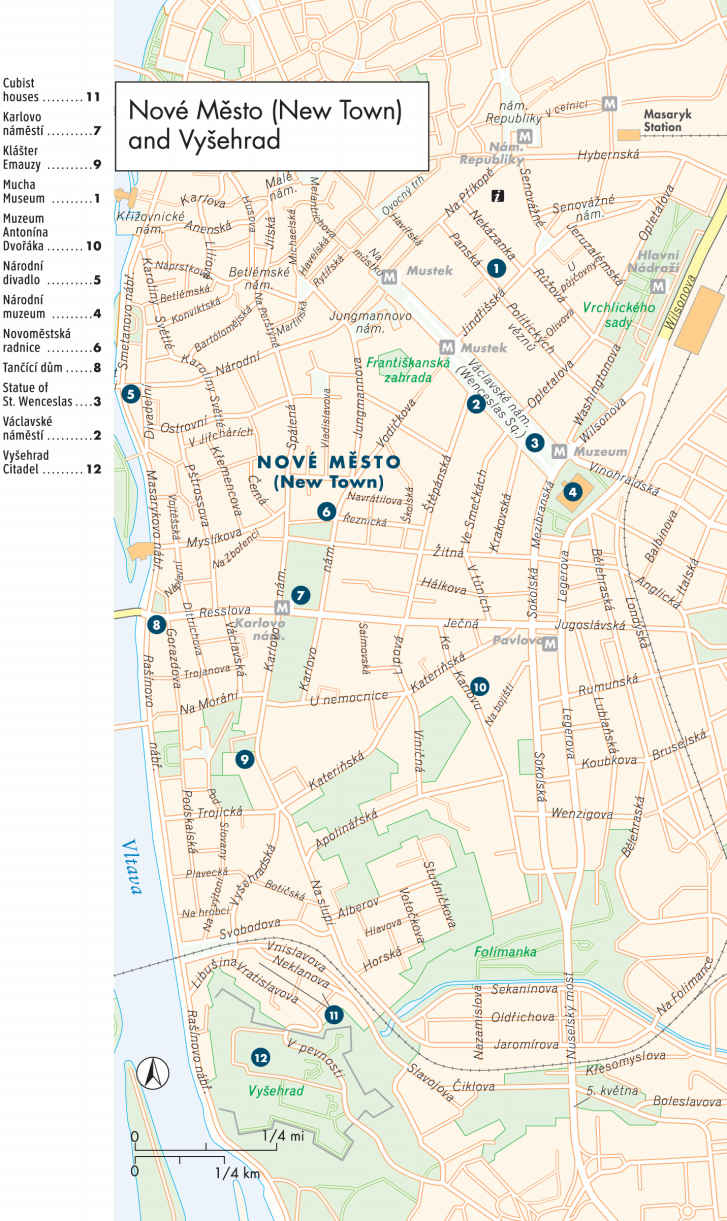

Beyond the former walls of the Old Town, the New Town fills in the south and east. The name “new” is a misnomer—New Town was laid out in the 14th century. (It’s new only when compared with the neighboring Old Town.) Today this mostly commercial district includes the city’s largest squares, Karlovo náměstí (Charles Square) and Václavské náměstí (Wenceslas Square).

STARÉ MĚSTO (OLD TOWN)

Old Town is usually the first stop for any visitor. Old Town Square, its gorgeous houses, and the astronomical clock are blockbuster attractions. On the other hand, the north end of Wenceslas Square—its base, the opposite end from the statue and the museum—is also a good place to begin a tour of Old Town. This “T” intersection marks the border between the old and new worlds in Prague. A quick glance around reveals the often jarring juxtaposition: centuries-old buildings sit side by side with modern retail names like Benetton and Starbucks.

GETTING HERE AND AROUND

There’s little public transit in the Old Town, so walking is really the most practical way to get around; you could take a cab, but it’s not worth the trouble. It takes about 15 minutes to walk from Náměstí Republiky to Staroměstská. If you’re coming to the Old Town from another part of Prague, three metro stops circumscribe the area: Staroměstská on the west, Náměstí Republiky on the east, and Můstek on the south, at the point where Old Town and Wenceslas Square meet.

TIMING

Wenceslas Square and Old Town Square teem with activity around the clock almost year-round. If you’re in search of a little peace and quiet, you can find the streets at their most subdued on early weekend mornings or when it’s cold. Remember to be in Old Town Square just before the hour if you want to see the astronomical clock in action.

TOP ATTRACTIONS

Clementinum.

The origins of this massive complex—now part of the university—date back to the 12th and 13th centuries, but it’s best known as the stronghold of the Jesuits, who occupied it for more than 200 years beginning in the early 1600s. Though many buildings are closed to the public, it’s well worth a visit. The Jesuits built a resplendent Baroque Library

, displaying fabulous ceiling murals that portray the three levels of knowledge, with the “Dome of Wisdom” as a centerpiece. Next door, the Mirror Chapel

is a symphony of reflective surfaces, with acoustics to match. Mozart played here, and the space still hosts chamber music concerts. The Astronomical Tower

in the middle of the complex was used by Johannes Kepler, and afterward functioned as the “Prague Meridian,” where the time was set each day. At high noon a timekeeper would appear on the balcony and wave a flag that could be seen from the castle, where a cannon was fired to mark the hour.  Mariánské nám. 5, Staré Mesto

Mariánské nám. 5, Staré Mesto

222–220–879

222–220–879

www.klementinum.com

www.klementinum.com

220 Kč, includes tour

220 Kč, includes tour

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Dům U černé Matky boží

(House of the Black Madonna

). In the second decade of the 20th century, young Czech architects boldly applied cubism’s radical reworking of visual space to architecture and design. This building, designed by Josef Gočár, is a shining example of this reworking. While there is no longer a museum here, you are free to admire the characteristic geometric lines and sharp angles of the building’s exterior.  Ovocný trh 19, Staré Mesto

Ovocný trh 19, Staré Mesto

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Jan Hus monument.

Few memorials in Prague elicited as much controversy as this one, dedicated in July 1915, exactly 500 years after Hus was burned at the stake in Constance, Germany. Some maintain that the monument’s Secessionist style (the inscription seems to come right from turn-of-the-20th-century Vienna) clashes with the Gothic and baroque style of the square. Others dispute the romantic depiction of Hus, who appears here as tall and bearded in flowing garb, whereas the real Hus, as historians maintain, was short and had a baby face. Either way, the fiery preacher’s influence is not in dispute. His ability to transform doctrinal disagreements, both literally and metaphorically, into the language of the common man made him into a religious and national symbol for the Czechs.  Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Kostel Matky Boží před Týnem

(Church of Our Lady Before Týn

). The twin-spired Týn Church is an Old Town Square landmark and one of the city’s best examples of Gothic architecture. The church’s exterior was in part the work of Peter Parler, the architect responsible for the Charles Bridge and St. Vitus Cathedral. Construction of the twin black-spire towers began a little later, in 1461, by King Jiří of Poděbrad, during the heyday of the Hussites. Jiří had a gilded chalice, the symbol of the Hussites, proudly displayed on the front gable between the two towers. Following the defeat of the Czech Protestants by the Catholic Hapsburgs in the 17th century, the chalice was melted down and made into the Madonna’s glimmering halo (you can still see it resting between the spires). Much of the interior, including the tall nave, was rebuilt

in the baroque style in the 17th century. Some Gothic pieces remain, however: look to the left of the main altar for a beautifully preserved set of early carvings. The main altar itself was painted by Karel Škréta, a luminary of the Czech baroque. The church also houses the tomb of renowned Danish (and Prague court) astronomer Tycho Brahe, who died in 1601.  Staroměstské nám. between Celetná and Týnská, Staré Mesto

Staroměstské nám. between Celetná and Týnská, Staré Mesto

222–318–186

222–318–186

www.tyn.cz

www.tyn.cz

Closed Mon.–Tues. in July and Aug.

Closed Mon.–Tues. in July and Aug.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Na příkopě.

The name means “At the Moat” and harks back to the time when the street was indeed a ditch separating the Old Town from the New Town. Today the pedestrian-only Na příkopě is prime shopping territory. Sleek modern buildings have been sandwiched between baroque palaces, the latter cut up inside to accommodate casinos, boutiques, and fast-food restaurants. The new structures are fairly identical inside, but near the eastern end of the block, Slovanský dům (No. 22) is worth a look. This late-18th-century structure has been tastefully refurbished and now houses fashionable shops, stylish restaurants, and one of the city’s best multiplex cinemas.  Na příkopě, Staré Mesto

.

Na příkopě, Staré Mesto

.

Obecní dům

(Municipal House

). The city’s art nouveau showpiece still fills the role it had when it was completed in 1911 as a center for concerts, rotating art exhibits, and café society. The mature art nouveau style echoes the lengths the Czech middle class went to at the turn of the 20th century to imitate Paris. Much of the interior bears the work of Alfons Mucha, Max Švabinský, and other leading Czech artists. Mucha decorated the Hall of the Lord Mayor upstairs with impressive, magical frescoes depicting Czech history; unfortunately it’s visible only as part of a guided tour. The beautiful Smetanova síň (Smetana Hall), which hosts concerts by the Prague Symphony Orchestra as well as international players, is on the second floor. The ground-floor restaurants are overcrowded with tourists but still impressive, with glimmering chandeliers and exquisite woodwork. There’s also a beer hall in the cellar, with decent food and ceramic murals on the walls. Tours are normally held at two-hour intervals in the afternoons; check the website for details.  Nám. Republiky 5, Staré Mesto

Nám. Republiky 5, Staré Mesto

222–002–101

222–002–101

www.obecnidum.cz

www.obecnidum.cz

Guided tours 380 Kč

Guided tours 380 Kč

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Hotel Paříž.

Head around the corner from Obecní dům to the café at the Hotel Paříž for the café analog of the Municipal House. It’s a Jugendstil jewel tucked away on a quiet side street. The lauded, haute-cuisine Restaurant Sarah Bernhardt is next door. At the café, the “old Bohemian” omelet with potatoes and bacon is enough fuel for a full day of sightseeing.  U Obecního domu 1, Staré Mesto

U Obecního domu 1, Staré Mesto

222–195–195

222–195–195

www.hotel-paris.cz

www.hotel-paris.cz

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Palác Kinských

(Kinský Palace

). This exuberant building, built in 1765 from Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer’s design, is considered one of Prague’s finest rococo, late baroque structures. With its exaggerated pink overlay and numerous statues, it looks extravagant when contrasted with the marginally more somber baroque elements of other nearby buildings. (The interior, alas, was “modernized” under communism.) The palace

once contained a German school—where Franz Kafka studied for nine misery-laden years—and now holds the National Gallery’s permanent collection of art and artifacts of ancient cultures of Asia and Africa. Communist leader Klement Gottwald, flanked by comrade Vladimír Clementis, first addressed the crowds from this building after seizing power in February 1948—an event recounted in the first chapter of Milan Kundera’s novel The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.

Staroměstské nám. 12, Staré Mesto

Staroměstské nám. 12, Staré Mesto

224–810–759

224–810–759

www.ngprague.cz

www.ngprague.cz

100 Kč

100 Kč

Closed Mon.

Closed Mon.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Prašná brána

(Powder Tower or Powder Gate

). Once used as storage space for gunpowder, this dark, imposing tower—covered in a web of carvings—offers a striking view of the Old Town and Prague Castle from the top. King Vladislav II of Jagiello began construction—it replaced one of the city’s 13 original gates—in 1475. At the time, kings of Bohemia maintained their royal residence next door, on the site now occupied by the Obecní dům. The tower was intended to be the grandest gate of all. Vladislav, however, was Polish, and somewhat disliked by the rebellious Czech citizens of Prague. Nine years after he assumed power, and fearing for his life, he moved the royal court across the river to Prague Castle. Work on the tower was abandoned, and the half-finished structure remained a depository for gunpowder until the end of the 17th century. The golden spires were not added until the end of the 19th century. The ticket office is on the first floor, after you go up the dizzyingly narrow stairwell.  Nám. Republiky 5/1090, Staré Mesto

Nám. Republiky 5/1090, Staré Mesto

725–847–875

725–847–875

www.muzeumprahy.cz

www.muzeumprahy.cz

75 Kč

75 Kč

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Line B: Náměstí Republiky

.

Fodor’s

Choice

Staroměstské náměstí

(Old Town Square

). The hype about Old Town Square is completely justified. Picture a perimeter of colorful baroque houses contrasting with the sweeping old-Gothic style of the Týn church in the background. The unexpectedly large size gives it a majestic presence as it opens up from feeder alleyways. As the heart of Old Town, the square grew to its present proportions when Prague’s original marketplace moved away from the river in the 12th century. Its shape and appearance have changed little since that time (the monument to religious reformer Jan Hus, at the center of the square, was erected in the early 20th century). During the day the square pulses with activity, as musicians vie for the attention of visitors milling about. In summer the square’s south end is dominated by sprawling outdoor restaurants. During the Easter and Christmas seasons it fills with wooden booths of vendors selling everything from simple wooden toys to fine glassware and

mulled wine. At night the brightly lighted towers of the Týn church rise gloriously over the glowing baroque façades.

Staroměstské náměstí

(Old Town Square

). The hype about Old Town Square is completely justified. Picture a perimeter of colorful baroque houses contrasting with the sweeping old-Gothic style of the Týn church in the background. The unexpectedly large size gives it a majestic presence as it opens up from feeder alleyways. As the heart of Old Town, the square grew to its present proportions when Prague’s original marketplace moved away from the river in the 12th century. Its shape and appearance have changed little since that time (the monument to religious reformer Jan Hus, at the center of the square, was erected in the early 20th century). During the day the square pulses with activity, as musicians vie for the attention of visitors milling about. In summer the square’s south end is dominated by sprawling outdoor restaurants. During the Easter and Christmas seasons it fills with wooden booths of vendors selling everything from simple wooden toys to fine glassware and

mulled wine. At night the brightly lighted towers of the Týn church rise gloriously over the glowing baroque façades.

But the square’s history is not all wine and music: During the 15th century the square was the focal point of conflict between Czech Hussites and the mainly Catholic Austrians and Germans. In 1422 the radical Hussite preacher Jan Želivský was executed here for his part in storming the New Town’s town hall three years earlier. In the 1419 uprising a judge, a mayor, and seven city council members were thrown out the window—the first of Prague’s many famous defenestrations. Within a few years the Hussites had taken over the town, expelled many of the Catholics, and set up their own administration.

Twenty-seven white crosses embedded in the square’s paving stones, at the base of Old Town Hall, mark the spot where 27 Bohemian noblemen were killed by the Austrian Habsburgs in 1621 during the dark days following the defeat of the Czechs at the Battle of White Mountain. The grotesque spectacle, designed to quash any further national or religious opposition, took about five hours to complete, as the men were put to the sword or hanged one by one.  Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Café au Gourmand.

Just outside of Old Town Square on Dlouhá Street, Café au Gourmand has a delightful selection of authentic French pastries, salads, and sandwiches. There’s also a small garden in the back where you can sit with your snacks.  Dlouhá 10

Dlouhá 10

222–329–060

222–329–060

www.augourmand.cz

www.augourmand.cz

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Fodor’s

Choice

Staroměstská radnice

(Old Town Hall

). This is a center of Prague life for tourists and locals alike. Hundreds of visitors gravitate here throughout the day to see the hour struck by the mechanical figures of the astronomical clock

. At the top of the hour, look to the upper part of the clock, where a skeleton begins by tolling a death knell and turning an hourglass upside down. The 12 apostles promenade by, and then a cockerel flaps its wings and screeches as the hour finally strikes. To the right of the skeleton, the dreaded Turk nods his head, almost hinting at another invasion like those of the 16th and 17th centuries. This theatrical spectacle doesn’t reveal the way this 15th-century marvel indicates the time—by the season, the zodiac sign, and the positions of the sun and moon. The calendar under the clock dates to the mid-19th century.

Staroměstská radnice

(Old Town Hall

). This is a center of Prague life for tourists and locals alike. Hundreds of visitors gravitate here throughout the day to see the hour struck by the mechanical figures of the astronomical clock

. At the top of the hour, look to the upper part of the clock, where a skeleton begins by tolling a death knell and turning an hourglass upside down. The 12 apostles promenade by, and then a cockerel flaps its wings and screeches as the hour finally strikes. To the right of the skeleton, the dreaded Turk nods his head, almost hinting at another invasion like those of the 16th and 17th centuries. This theatrical spectacle doesn’t reveal the way this 15th-century marvel indicates the time—by the season, the zodiac sign, and the positions of the sun and moon. The calendar under the clock dates to the mid-19th century.

Old Town Hall served as the center of administration for Old Town beginning in 1338, when King John of Luxembourg first granted the city council the right to a permanent location. The impressive 200-foot Town Hall Tower, where the clock is mounted, was first built in the 14th century. For a rare view of the Old Town and its maze of crooked streets and alleyways, climb the ramp or ride the elevator to the top of the tower.

Walking around the hall to the left, you can see it’s actually a series of houses jutting into the square; they were purchased over the years and successively added to the complex. On the other side, jagged stonework reveals where a large, neo-Gothic wing once adjoined the tower until it was destroyed by fleeing Nazi troops in May 1945.

Tours of the interiors depart from the main desk inside (most guides speak English, and English texts are on hand). There’s also a branch of the tourist information office here. Previously unseen parts of the tower have now been opened to the public, and you can now see the inside of the famous clock.  Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

www.staromestskaradnicepraha.cz

www.staromestskaradnicepraha.cz

130 Kč

130 Kč

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Hotel U Prince.

With an entrance diagonally opposite the astronomical clock, Hotel U Prince has an impressive rooftop view. Go through the arched entryway to the right and walk all the way to the back, where you’ll find a glass-door elevator. Take the elevator to the rooftop bar, which has covered seating and portable heaters running in cold weather. Be forewarned though: the view doesn’t come cheap.  Staroměstká nám. 29

Staroměstká nám. 29

224–213–807

224–213–807

www.hoteluprince.com

www.hoteluprince.com

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

WORTH NOTING

Betlémská kaple

(Bethlehem Chapel

). The original church was built at the end of the 14th century, and the Czech religious reformer Jan Hus was a regular preacher here from 1402 until his exile in 1412. Here he gave the mass in “vulgar” Czech—not in Latin as the church in Rome demanded. After the Thirty Years’ War in the 17th century, the chapel fell into the hands of the Jesuits and was demolished in 1786. Excavations carried out after World War I uncovered the original portal and three windows; the entire church was reconstructed during the 1950s. Although little remains of the first church, some remnants of Hus’s teachings can still be read on the inside walls.  Betlémské nám. 3, Staré Mesto

Betlémské nám. 3, Staré Mesto

224–248–595

224–248–595

60 Kč

60 Kč

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Celetná ulice.

This is the main thoroughfare, which connects Old Town Square and Náměstí Republiky; it’s packed day and (most of the) night. Many of the street’s façades are styled in classic 17th- or 18th-century manner, but appearances are deceiving: nearly all of the houses in fact have foundations that date back to the 12th century. Be sure to look above the street-level storefronts to see the fine examples of baroque detail.  Celetná ulice, Staré Mesto

.

Celetná ulice, Staré Mesto

.

Clam-Gallas palác

(Clam-Gallas Palace

). The work of Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach, the famed Viennese baroque virtuoso of the day, is

showcased in this earth-tone palace. Construction began in 1713 and finished in 1729. Clam-Gallas palác serves as a state archive, but is also occasionally used to house temporary art exhibitions and concerts. If the building is open, try walking in to glimpse the Italian frescoes depicting Apollo and the battered but intricately carved staircase, done by the master himself.  Husova 20, Staré Mesto

Husova 20, Staré Mesto

Free

Free

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Klášter svaté Anežky České

(St. Agnes’s Convent

). Near the river between Pařížská and Revoluční streets, in the northeastern corner of the Old Town, this peaceful complex has Prague’s first buildings in the Gothic style. Built between the 1230s and the 1280s, the convent provides a fitting home for the National Gallery’s marvelous collection of Czech Gothic art, including altarpieces, portraits, and statues from the 13th to the 16th century.  U Milosrdných 17, Staré Mesto

U Milosrdných 17, Staré Mesto

224–810–628

224–810–628

www.ngprague.cz

www.ngprague.cz

150 Kč

150 Kč

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Kostel svatého Jiljí

(Church of St. Giles

). Replete with buttresses and a characteristic portal, this church’s exterior is a powerful example of Gothic architecture. An important outpost of Czech Protestantism in the 16th century, the church reflects baroque style inside, with a design by Johann Bernhard Fischer von Erlach and sweeping frescoes by Václav Reiner. The interior can be viewed during the day from the vestibule or at the evening concerts held several times a week.  Husova 8, Staré Mesto

Husova 8, Staré Mesto

224–220–235

224–220–235

www.praha.op.cz

www.praha.op.cz

Free

Free

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Kostel svatého Martina ve zdi

(Church of St. Martin-in-the-Wall

). It was here in 1414 that Holy Communion was first given to the Bohemian laity in the form of both bread and wine. (The Catholic custom of the time dictated only bread would be offered to the masses, with wine reserved for priests and clergy.) From then on, the chalice came to symbolize the Hussite movement. The church is sometimes open for evening concerts, held often in summer, or for Sunday service, but that’s the only way to see the rather plain interior.  Martinská 8, Staré Mesto

Martinská 8, Staré Mesto

www.martinvezdi.eu

www.martinvezdi.eu

Lines A & B: Můstek

.

Lines A & B: Můstek

.

Kostel svatého Mikuláše

(Church of St. Nicholas

). Designed in the 18th century by Prague’s own master of late baroque, Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer, this church is probably less successful in capturing the style’s lyric exuberance than its namesake across town, the Chrám svatého Mikuláše. But Dientzenhofer utilized the limited space to create a well-balanced structure. The interior is compact, with a beautiful, small chandelier and an enormous black organ that overwhelms the rear of the church. Afternoon and evening concerts for visitors are held almost continuously—walk past and you’re sure to get leafleted for one.  Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

Staroměstské nám., Staré Mesto

www.svmikulas.cz

www.svmikulas.cz

Free, fee for concerts

Free, fee for concerts

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Malé náměstí

(Small Square

). Note the iron fountain dating to around 1560 in the center of the square. The colorfully painted house at No. 3 was originally a hardware store (and now, confusingly, is the site of a Hard Rock Cafe). It’s not as old as it looks, but you can find authentic

Gothic portals and Renaissance sgraffiti

that reflect the square’s true age in certain spots.  Malé náměstí, Staré Mesto

Malé náměstí, Staré Mesto

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Muzeum hlavního města Prahy

(Museum of the City of Prague

). This museum is dedicated to the history of the city, and though it’s technically in Nové Město, it’s relatively easy to reach from Old Town because it’s near the Florenc metro and bus stations. The highlight here is a cardboard model of the historic quarter of Prague; it shows what the city looked like before the Jewish ghetto was destroyed in a massive fire in 1689 and includes many buildings that are no longer standing.  Na Pořící 52, Nové Mesto

Na Pořící 52, Nové Mesto

224–816–772

224–816–772

www.muzeumprahy.cz

www.muzeumprahy.cz

120 Kč

120 Kč

Closed Mon.

Closed Mon.

Lines B & C: Florenc

.

Lines B & C: Florenc

.

Stavovské divadlo

(Estates Theater

). Built in the 1780s in the classical style, this opulent, green palais

hosted the world premiere of Mozart’s opera Don Giovanni

in October 1787 with the composer himself conducting. Prague audiences were quick to acknowledge Mozart’s genius: the opera was an instant hit here, though it flopped nearly everywhere else in Europe. Mozart wrote some of the opera’s second act in Prague at the Villa Bert, where he was a frequent guest. The program these days is mostly demanding Czech drama, though you can occasionally catch a more accessible opera or musical performance. You must attend a performance to see inside; buy tickets at the Narodní Divadlo.  Ovocný trh 1, Staré Mesto

Ovocný trh 1, Staré Mesto

224–901–448 for box office

224–901–448 for box office

www.narodni-divadlo.cz

www.narodni-divadlo.cz

Lines A & B: Můstek

.

Lines A & B: Můstek

.

JOSEFOV (JEWISH QUARTER)

For centuries Prague had an active, vital Jewish community that was an exuberant part of the city’s culture. Much of that activity was concentrated in Josefov, the former Jewish ghetto, just a short walk north of Old Town Square. This area first became a Jewish settlement around the 12th century, but it didn’t actually take on the physical aspects of a ghetto—walled off from the rest of the city—until much later.

The history of Prague’s Jews, like those of much of Europe, is mostly a sad one. There were horrible pogroms in the late Middle Ages, followed by a period of relative prosperity under Rudolf II in the late 16th century, though the freedoms of Jews were still tightly restricted. It was Austrian Emperor Josef II—the ghetto’s namesake—who did the most to improve the conditions of the city’s Jews. His “Edict of Tolerance” in 1781 removed dress codes for Jews and paved the way for Jews finally to live in other parts of the city.

The prosperity of the 19th century lifted the Jews out of poverty, and many of them chose to leave the ghetto. By the end of the century the number of poor gentiles, drunks, and prostitutes in the ghetto was growing, and the number of actual Jews was declining. At this time, city officials decided to clear the slum and raze the buildings. In their place they built many of the gorgeous turn-of-the-20th-century and art nouveau town houses you see today. Only a handful of the synagogues, the town hall, and the cemetery were preserved.

World War II and the Nazi occupation brought profound tragedy to the city’s Jews. A staggering percentage were deported—many to Terezín, north of Prague, and then later to German Nazi death camps in Poland. Of the 40,000 Jews living in Prague before World War II, only about 1,200 returned after the war, and merely a handful live in the ghetto today.

The Nazi occupation contains a historic irony. Many of the treasures stored away in Prague’s Jewish Museum were brought here from across Central Europe on Hitler’s orders. His idea was to form a museum dedicated to the soon-to-be extinct Jewish race.

Today, even with the crowds, the ghetto is a must-see. The Old Jewish Cemetery alone, with its incredibly forlorn overlay of headstone upon headstone going back centuries, merits the steep admission price the Jewish Museum charges to see its treasures. Don’t feel compelled to linger long on the ghetto’s streets after visiting, though—much of it is tourist-trap territory, filled with overpriced T-shirt, trinket, and toy shops—the same lousy souvenirs found everywhere in Prague.

A ticket to the Židovské muzeum v Praze (Prague Jewish Museum) includes admission to the Old Jewish Cemetery and collections installed in four surviving synagogues and the Ceremony Hall. The Staronová synagóga, or Old-New Synagogue, a functioning house of worship, does not technically belong to the museum, and requires a separate admission ticket.

GETTING HERE AND AROUND

The Jewish Quarter is one of the most heavily visited areas in Prague, especially in peak tourist seasons, when its tiny streets are jammed to bursting. The best way to visit is on foot—it’s a short hop over from Old Town Square.

TIMING

The best time for a visit (read: quiet and less crowded) is early morning, when the museums and cemetery first open. The area itself is very compact, and a fairly thorough tour should take only half a day. Don’t go on the Sabbath (Saturday), when all the museums are closed.

TOP ATTRACTIONS

Klausová synagóga

(Klausen Synagogue

). This baroque synagogue displays objects from Czech Jewish traditions, with an emphasis on celebrations and daily life. The synagogue was built at the end of the 17th century in place of three small buildings (a synagogue, a school, and a ritual bath) that were destroyed in a fire that devastated the ghetto in 1689. In the more recent Obřadní síň

(Ceremony Hall) that adjoins the Klausen Synagogue, the focus is more staid. You’ll find a variety of Jewish funeral paraphernalia, including old gravestones, and medical instruments. Special attention is paid to the activities of the Jewish Burial Society through many fine objects and paintings.  U starého hřbitova 3A, Josefov

U starého hřbitova 3A, Josefov

222–317–191

222–317–191

www.jewishmuseum.cz

www.jewishmuseum.cz

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Les Moules.

Crave a culinary change from constant meat and potatoes? Try the Belgian-styled bistro Les Moules, at the end of Maiselova. There’s a nice open terrace and a fine selection of mussels, as you’d expect from

the name. If you’re tired of Pilsner Urquell, too, they have a variety of Belgian Trappist beers.  Pařižská 19, Staré Mesto

Pařižská 19, Staré Mesto

222–315–022

222–315–022

www.lesmoules.cz

www.lesmoules.cz

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Maiselova synagóga.

The history of Czech Jews from the 10th to the 18th century is illustrated, accompanied by some of the Prague Jewish Museum’s most precious objects. The collection includes silver Torah shields and pointers, spice boxes, and candelabra; historic tombstones; and fine ceremonial textiles—some donated by Mordechai Maisel to the very synagogue he founded. The glitziest items come from the late 16th and early 17th centuries, a prosperous era for Prague’s Jews.  Maiselova 10, Josefov

Maiselova 10, Josefov

222–317–191

222–317–191

www.jewishmuseum.cz

www.jewishmuseum.cz

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Pinkasova synagóga

(Pinkas Synagogue

). Here you’ll find two moving testimonies to the appalling crimes perpetrated against the Jews during World War II. One astounds by sheer numbers: the walls are covered with nearly 80,000 names of Bohemian and Moravian Jews murdered by the Nazis. Among them are the names of the paternal grandparents of former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright. The second is

an exhibition of drawings made by children at the Nazi concentration camp Terezín, north of Prague. The Nazis used the camp for propaganda purposes to demonstrate their “humanity” toward Jews, and for a time the prisoners were given relative freedom to lead “normal” lives. However, transports to death camps in Poland began in earnest in 1944, and many thousands of Terezín prisoners, including most of these children, eventually perished. The entrance to the Old Jewish Cemetery is through this synagogue.  Široká 3, Josefov

Široká 3, Josefov

222–317–191

222–317–191

www.jewishmuseum.cz

www.jewishmuseum.cz

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Rudolfinum.

This 19th-century neo-Renaissance monument has some of the cleanest, brightest stonework in the city. Designed by Josef Zítek and Josef Schulz and completed in 1884—it was named for then Hapsburg Crown Prince Rudolf—the low-slung sandstone building was meant to be a combination concert hall and exhibition gallery. After 1918 it was converted into the parliament of the newly independent Czechoslovakia until German invaders reinstated the concert hall in 1939. Now the Czech Philharmonic has its home base here. The 1,200-seat Dvořákova síň

(Dvořák Hall) has superb acoustics (the box office faces 17 Listopadu Street). To see the hall, you must attend a concert.  Alšovo nábřeží 12, Josefov

Alšovo nábřeží 12, Josefov

227–059–227

227–059–227

www.rudolfinum.cz

www.rudolfinum.cz

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Staronová synagóga

(Old-New Synagogue, or Altneuschul

). Dating to the mid-13th century, this is the oldest functioning synagogue in Europe and one of the most important works of early Gothic in Prague. The name refers to the legend that the synagogue was built on the site of an ancient Jewish temple, and the temple’s stones were used to build the present structure. Amazingly, the synagogue has survived fires, the razing of the ghetto, and the Nazi occupation intact; it’s still in use. The entrance, with its vault supported by two pillars, is the oldest part of the synagogue. Note that men are required to cover their heads inside, and during services men and women sit apart.  Červená 2, Josefov

Červená 2, Josefov

222–317–191

222–317–191

www.jewishmuseum.cz

www.jewishmuseum.cz

200 Kč

200 Kč

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Fodor’s

Choice

Starý židovský hřbitov

(Old Jewish Cemetery

). An unforgettable sight, this cemetery is where all Jews living in Prague from the 15th century to 1787 were laid to rest. The lack of any space in the tiny ghetto forced graves to be piled on top of one another. Tilted at crazy angles, the 12,000 visible tombstones are but a fraction of countless thousands more buried below. Walk the path amid the gravestones; the relief symbols you see represent the names and professions of the deceased. The oldest marked grave belongs to the poet Avigdor Kara, who died in 1439; the grave is not accessible from the pathway, but the original tombstone can be seen in the Maisel Synagogue. The best-known marker belongs to Jehuda ben Bezalel, the famed Rabbi Loew (died 1609), a chief rabbi of Prague and a profound scholar, credited with creating the mythical Golem. Even today, small scraps of paper bearing wishes are stuffed into the cracks of

the rabbi’s tomb with the hope that he will grant them. Loew’s grave lies near the exit.

Starý židovský hřbitov

(Old Jewish Cemetery

). An unforgettable sight, this cemetery is where all Jews living in Prague from the 15th century to 1787 were laid to rest. The lack of any space in the tiny ghetto forced graves to be piled on top of one another. Tilted at crazy angles, the 12,000 visible tombstones are but a fraction of countless thousands more buried below. Walk the path amid the gravestones; the relief symbols you see represent the names and professions of the deceased. The oldest marked grave belongs to the poet Avigdor Kara, who died in 1439; the grave is not accessible from the pathway, but the original tombstone can be seen in the Maisel Synagogue. The best-known marker belongs to Jehuda ben Bezalel, the famed Rabbi Loew (died 1609), a chief rabbi of Prague and a profound scholar, credited with creating the mythical Golem. Even today, small scraps of paper bearing wishes are stuffed into the cracks of

the rabbi’s tomb with the hope that he will grant them. Loew’s grave lies near the exit.  Široká 3, enter through Pinkasova synagóga, Josefov

Široká 3, enter through Pinkasova synagóga, Josefov

222–317–191

222–317–191

www.jewishmuseum.cz

www.jewishmuseum.cz

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Uměleckoprůmyslové museum v Praze

(Museum of Decorative Arts or U(P)M

). In a custom-built art nouveau building from 1897, this wonderfully laid-out museum of exquisite local prints, books, ceramics, textiles, clocks, and furniture will please anyone from the biggest decorative arts expert to those who just appreciate a little Antiques Roadshow

on the weekend. Superb rotating exhibits, too.  17. listopadu 2, Josefov

17. listopadu 2, Josefov

251–093–111

251–093–111

www.upm.cz

www.upm.cz

120 Kč

120 Kč

Closed Mon.

Closed Mon.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

WORTH NOTING

Španělská synagóga

(Spanish Synagogue

). This domed, Moorish-style synagogue was built in 1868 on the site of an older synagogue, the Altschul. Here the historical exposition that begins in the Maisel Synagogue continues to the post–World War II period. The attached Robert Guttmann Gallery has historic and well-curated art exhibitions. The building’s painstakingly restored interior is also worth experiencing.  Vězeňská 1, Josefov

Vězeňská 1, Josefov

222–317–191

222–317–191

www.jewishmuseum.cz

www.jewishmuseum.cz

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

300 Kč museums only, 200 Kč Old-New Synagogue

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

.

Closed Sat. and during Jewish holidays

.

Židovská radnice

(Jewish Town Hall

). The hall was the creation of Mordechai Maisel, an influential Jewish leader at the end of the 16th century. Restored in the 18th century, it was given a clock and bell tower at that time. A second clock, with Hebrew numbers, keeps time counterclockwise. Now a Jewish Community Center, the building also houses Shalom, a kosher restaurant. Neither the hall nor the restaurant is open to the public, but the beautiful building is worth seeing from the outside.  Maiselova 18, Josefov

Maiselova 18, Josefov

Line A: Staroměstská

.

Line A: Staroměstská

.

MALÁ STRANA (LESSER QUARTER)

Established in 1257, this is Prague’s most perfectly formed—yet totally asymmetrical—neighborhood. Also known as “Little Town,” it was home to the merchants and craftsmen who served the royal court. Though not nearly as confusing as the labyrinth that is Old Town, the streets in the Lesser Quarter can baffle, but they also bewitch, and today the area holds embassies, Czech government offices, historical attractions, and galleries mixed in with the usual glut of pubs, restaurants, and souvenir shops.

GETTING HERE AND AROUND

Metro Line A will lead you to Malá Strana, the Malostranká station being the most central stop (from here, take Tram No. 12, 20, or 26 one stop to Malostranké náměstí). But there’s no better way to arrive at Malá Strana than via a scenic downhill walk from the Castle or a lovely stroll from Old Town across the Charles Bridge.

TIMING

Note that the heat builds up during the day in this area—as do the crowds—so it’s best visited before noon or in early evening. On literally every block there are plenty of cafés in which to stop, sip coffee or tea, and people-watch, and a wealth of gardens and parks ideal for resting in cool shade. As with the other most popular neighborhoods of Prague—Old Town, New Town, and the Castle Area—there are fewer crowds in the early morning or in the bitter cold. (The former is preferable over the latter.)

TOP ATTRACTIONS

Chrám svatého Mikuláše

(Church of St. Nicholas

). With its dynamic curves, this church is arguably the purest and most ambitious example of high baroque in Prague. The celebrated architect Christoph Dientzenhofer began the Jesuit church in 1704 on the site of one of the more active Hussite churches of 15th-century Prague. Work on the building was taken over by his son Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer, who built the dome and presbytery. Anselmo Lurago completed the whole thing in 1755 by adding the bell tower. The juxtaposition of the broad, full-bodied dome with the slender bell tower is one of the many striking architectural contrasts that mark the Prague skyline. Inside, the vast pink-and-green space is impossible to take in with a single glance. Every corner bristles with life, guiding the eye first to the dramatic statues, then to the hectic frescoes, and on to the shining faux-marble pillars. Many of the statues are the work of Ignaz Platzer and constitute his last blaze of success. Platzer’s workshop was forced to declare bankruptcy when the centralizing and secularizing reforms of Joseph II toward the end of the 18th century brought an end to the flamboyant baroque era. The tower, with an entrance on the side of the church, is open in summer. The church also hosts chamber music concerts in summer, which complement this eye-popping setting but do not reflect the true caliber of classical music in Prague. For that, check the schedule posted across the street at Líchtenšký palác,

where the faculty of HAMU, the city’s premier music academy, sometimes also gives performances.  Malostranské nám., Malá Strana

Malostranské nám., Malá Strana

257–534–215

257–534–215

www.stnicholas.cz

www.stnicholas.cz

Tower 70 Kč, concerts 490 Kč

Tower 70 Kč, concerts 490 Kč

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Franz Kafka Museum.

The great early-20th-century Jewish author Kafka wasn’t considered Czech and he wrote in German, but he lived in Prague nearly his entire short, anguished life, so it’s fitting that he’s finally gotten the shrine he deserves here. Because the museum’s designers believed in channeling Kafka’s darkly paranoid and paradoxical work, they created exhibits true to this spirit. And even if the results are often goofy, they get an “A” for effort. Facsimiles of manuscripts, documents, first editions, photographs, and newspaper obits are displayed in glass vitrines, which in turn are situated in “Kafkaesque” settings: huge open filing cabinets, stone gardens, piles of coal. The basement level of the museum gets even freakier, with expressionistic representations of Kafka’s work itself, including a model of the horrible torture machine from the “Penal Colony” story—not a place for young children, or even lovers on a first date, but fascinating to anyone familiar with Kafka’s work. Other Kafka sites in Prague include his home on Golden Lane, his Old Town birthplace at Náměstí Franze Kafky 3, and Jaroslav Rona’s trippy bronze sculpture of the writer on Dušní Street in the Old Town. (Speaking of sculptures, take a gander at the animatronic Piss

statue in the Kafka Museum’s courtyard. This rendition of a couple urinating into a fountain shaped like the Czech Republic was made by local enfant terrible sculptor David Černy, who also did the babies crawling up the Žižkov TV Tower.)  Hergetova Cihelna, Cihelna 2b, Malá

Strana

Hergetova Cihelna, Cihelna 2b, Malá

Strana

257–535–507

257–535–507

www.kafkamuseum.cz

www.kafkamuseum.cz

180 Kč

180 Kč

Line A: Malostranská

.

Line A: Malostranská

.

Kampa.

FAMILY

Prague’s largest “island” is cut off from the “mainland” by the narrow Čertovka streamlet. The name Čertovka, or “Devil’s Stream,” reputedly refers to a cranky old lady who once lived on Maltese Square. During the historic 2002 floods, the well-kept lawns of the Kampa Gardens,

which occupy much of the island, were covered as was much of the lower portion of Malá Strana. Evidence of flood damage occasionally marks the landscape, along with a sign indicating where the waters crested.  Kampa, Malá Strana

Kampa, Malá Strana

Line A: Malostranská

.

Line A: Malostranská

.

Fodor’s

Choice

Karlův most

(Charles Bridge).

This is Prague’s signature monument. The view from the foot of the bridge on the Old Town side, encompassing the towers and domes of the Lesser Quarter and the soaring spires of St. Vitus’s Cathedral, is breathtaking. After several wooden bridges and the first stone bridge washed away in floods, Charles IV appointed the 27-year-old German Peter Parler, the architect of St. Vitus’s Cathedral, to build a new structure in 1357. It became one of the wonders of the world in the Middle Ages. Its heavenly vista subtly changes in perspective as you walk across the bridge, attended by a host of baroque saints from the late 17th century (most now copies) that decorate the bridge’s peaceful Gothic stones. For more information, see the highlighted feature in this chapter.

Karlův most

(Charles Bridge).

This is Prague’s signature monument. The view from the foot of the bridge on the Old Town side, encompassing the towers and domes of the Lesser Quarter and the soaring spires of St. Vitus’s Cathedral, is breathtaking. After several wooden bridges and the first stone bridge washed away in floods, Charles IV appointed the 27-year-old German Peter Parler, the architect of St. Vitus’s Cathedral, to build a new structure in 1357. It became one of the wonders of the world in the Middle Ages. Its heavenly vista subtly changes in perspective as you walk across the bridge, attended by a host of baroque saints from the late 17th century (most now copies) that decorate the bridge’s peaceful Gothic stones. For more information, see the highlighted feature in this chapter.

Bohemia Bagel.

This informal breakfast and sandwich spot is just steps away from the Charles Bridge. When it opened more than a decade ago, it was a welcome addition for homesick expats as it was the first chain in town to offer homemade bagels, along with soups and salads.  Lázenská 19, Malá Strana

Lázenská 19, Malá Strana

257–218–192

257–218–192

www.bohemiabagel.cz

www.bohemiabagel.cz

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Kostel Panny Marie vítězné

(Church of Our Lady Victorious

). This aging, well-appointed church on the Lesser Quarter’s main street is the unlikely home of Prague’s most famous religious artifact, the Pražské Jezulátko (Infant Jesus of Prague). Originally brought to Prague from Spain in the 16th century, the wax doll holds a reputation for bestowing miracles on many who have prayed for its help. A measure of its widespread attraction is reflected in the prayer books on the kneelers in front of the statue, which have prayers of intercession in 20 different languages. The “Bambino,” as he’s known locally, has an enormous and incredibly ornate wardrobe, some of which is on display in a museum upstairs. Nuns from a nearby convent change the outfit on the statue regularly. Don’t miss the souvenir shop (accessible via a doorway to the right of the main altar), where the Bambino’s custodians flex their marketing skills.  Karmelitská 9A, Malá Strana

Karmelitská 9A, Malá Strana

257–533–646

257–533–646

www.pragjesu.cz

www.pragjesu.cz

Free

Free

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Malostranské náměstí

(Lesser Quarter Square

). Another one of the many classic examples of Prague’s charm, this square is flanked on the east and south sides by arcaded houses dating from the 16th and 17th centuries. The Czech Parliament resides partly in the gaudy yellow-and-green palace on the square’s north side, partly in a building on

Sněmovní Street, behind the palace. The huge bulk of the Church of St. Nicholas divides the lower, busier section—buzzing with restaurants, street vendors, clubs, and shops—from the slightly quieter upper part.  Malá Strana

.

Malá Strana

.

Museum Kampa.

The spotlighted jewel on Kampa Island is a remodeled flour mill that displays a private collection of paintings by Czech artist František Kupka and first-rate temporary exhibitions by both Czech and other Central European visual wizards. The museum was hit hard by flooding in 2002 and 2013, but rebounded relatively quickly on both occasions. The outdoor terrace offers a splendid view of the river and historic buildings on the opposite bank.  U Sovových mlýnů 2, Malá Strana

U Sovových mlýnů 2, Malá Strana

257–286–113

257–286–113

www.museumkampa.cz

www.museumkampa.cz

240 Kč

240 Kč

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Nerudova ulice. This steep street used to be the last leg of the “Royal Way,” the king’s procession before his coronation. As king, he made the ascent on horseback, not huffing and puffing on foot like today’s visitors. It was named for the 19th-century Czech journalist and poet Jan Neruda, after whom Chilean poet Pablo Neruda renamed himself. Until Joseph II’s administrative reforms in the late 18th century, house numbering was unknown in Prague. Each house bore a name, depicted on the façade, and these are particularly prominent on Nerudova ulice. AT No. 6, U červeného orla (At the Red Eagle) proudly displays a faded painting of a crimson eagle. Number 12 is known as U tří housliček (At the Three Fiddles); in the early 18th century three generations of the Edlinger violin-making family lived here. Joseph II’s scheme numbered each house according to its position in the “town” (here, the Lesser Quarter) to which it belonged, rather than its sequence on the street. The red plates record the original house numbers, but the blue ones are the numbers used in addresses today. Many architectural guides refer to the old, red-number plates, much to the confusion of visitors.

Two large palaces break the unity of the houses on Nerudova ulice. Both were designed by the adventurous baroque architect Giovanni Santini, one of the popular Italian builders hired by wealthy nobles in the early 18th century. The Morzin Palace, on the left at No. 5, is now the Romanian Embassy. The fascinating façade, created in 1713 with an allegory of night and day, is the work of Ferdinand Brokoff, of Charles Bridge statue fame. Across the street at No. 20 is the Thun-Hohenstein Palace, now the Italian Embassy. The gateway with two enormous eagles (the emblem of the Kolovrat family, who owned the building at the time) is the work of the other great Charles Bridge statue sculptor, Mathias Braun. Santini himself lived at No. 14, the Valkoun House.

The archway at No. 13 is a prime example of the many winding passageways that give the Lesser Quarter its captivatingly ghostly character at night. Higher up the street at No. 33 is the Bretfeld Palace,

a rococo house on the corner of Jánský vršek. The relief of St. Nicholas on the façade was created by Ignaz Platzer, a sculptor known for his classical and rococo work. But it’s the building’s historical associations that give it intrigue: Mozart, his librettist partner Lorenzo da Ponte, and the aging but still infamous philanderer and music lover Casanova

stayed here at the time of the world premiere of Don Giovanni

in 1787.  Nerudova ulice

.

Nerudova ulice

.

Petřínské sady FAMILY (Petřín Park or Petřín Gardens ). For a superb view of the city—from a slightly more solitary perch—the park on top of Petřín Hill includes a charming playground for children and adults alike, with a miniature (but still pretty big) Eiffel Tower. You’ll also find a mirror maze (bludiště ), as well as a working observatory and the seemingly abandoned Svatý Vavřinec (St. Lawrence) church. To get here from Malá Strana, simply hike up Petřín Hill (from Karmelitská ulice or Újezd) or ride the funicular railway (which departs near the Újezd tram stop). Regular public-transportation tickets are valid on the funicular.

From the Castle district, you can also stroll over from Strahov klášter (Strahov Monastery), following a wide path that crosses above some fruit orchards and offers some breathtaking views out over the city below.  Petřín Hill, Malá Strana

Petřín Hill, Malá Strana

www.muzeumprahy.cz

www.muzeumprahy.cz

Observatory 65 Kč, tower 120 Kč, maze 90 Kč

Observatory 65 Kč, tower 120 Kč, maze 90 Kč

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22 to Újezd (plus funicular)

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22 to Újezd (plus funicular)

.

Valdštejnska Zahrada

(Wallenstein Palace Gardens

). With its idiosyncratic high-walled gardens and superb, vaulted Renaissance sala terrena

(room opening onto a garden), this palace displays superbly elegant grounds. Walking around the formal paths, you come across numerous fountains and statues depicting figures from classical mythology or warriors dispatching a variety of beasts. However, nothing beats the trippy “Grotto,” a huge dripstone wall packed with imaginative rock formations, like little faces and animals hidden in the charcoal-colored landscape, and what’s billed as “illusory hints of secret corridors.” Here, truly, staring at the wall is a form of entertainment. Albrecht von Wallenstein, onetime owner of the house and gardens, began a meteoric military career in 1622, when the Austrian emperor Ferdinand II retained him to save the empire from the Swedes and Protestants during the Thirty Years’ War. Wallenstein, wealthy by marriage, offered to raise an army of 20,000 men at his own cost and lead them personally. Ferdinand II accepted and showered Wallenstein with confiscated land and titles. Wallenstein’s first acquisition was this enormous area. After knocking down 23 houses, a brick factory, and three gardens, in 1623 he began to build his magnificent palace. Most of the palace itself now serves the Czech Senate as meeting chamber and offices. The palace’s cavernous former Jízdárna, or riding school, now hosts art exhibitions.

Letenská 10, Malá Strana

Letenská 10, Malá Strana

257–075–707

257–075–707

www.senat.cz

www.senat.cz

Free

Free

Line A: Malostranská

.

Line A: Malostranská

.

Vrtbovská zahrada

(Vrtba Garden

). An unobtrusive door on noisy Karmelitská hides the entranceway to a fascinating sanctuary with one of the best views of the Lesser Quarter. The street door opens onto the intimate courtyard of the Vrtbovský palác (Vrtba Palace). Two Renaissance wings flank the courtyard; the left one was built in 1575, the right one in 1591. The original owner of the latter house was one of the 27 Bohemian nobles executed by the Habsburgs in 1621. The house was given as confiscated property to Count Sezima of Vrtba, who bought the neighboring property and turned the buildings into a late-Renaissance palace. The Vrtba Garden was created a century later. Built in five levels rising behind the courtyard in a wave of statuary-bedecked staircases and formal terraces reaching toward a seashell-decorated pavilion at the top, it’s a popular spot for weddings, receptions, and occasional concerts. (The fenced-off garden immediately behind and above belongs to the U.S. Embassy—hence the U.S. flag that often flies there.) The powerful stone figure of Atlas that caps the entranceway in the courtyard and most of the other statues of mythological figures are from the workshop of Mathias Braun, perhaps the best of the Czech baroque sculptors.  Karmelitská 25, Malá Strana

Karmelitská 25, Malá Strana

272–088–350

272–088–350

www.vrtbovska.cz

www.vrtbovska.cz

65 Kč

65 Kč

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

WORTH NOTING

Palácové zahrady pod Pražským hradem

(Gardens Below Prague Castle

). A break in the houses along Valdštejnská ulice opens to a gate that leads to five beautifully manicured and terraced baroque gardens, which in season are open to the public. A combined-entry ticket allows you to wander at will, climbing up and down the steps and trying to find the little entryways that lead from one garden to the next. Each of the gardens bears the name of a noble family and includes the Kolowrat (Kolovratská zahrada), Ledeburg (Ledeburská zahrada), Small and Large Palffy (Malá a Velká Pálffyovská zahrada), and Furstenberg (Furstenberská zahrada). You can also enter directly from the upper, south gardens of Prague Castle in summer.  Valdštejnská 12–14, Malá Strana

Valdštejnská 12–14, Malá Strana

257–214–817

257–214–817

www.palacove-zahrady.cz

www.palacove-zahrady.cz

90 Kč

90 Kč

Line A: Malostranská

.

Line A: Malostranská

.

Schönbornský palác

(Schönborn Palace

). Franz Kafka had an apartment in this massive baroque building at the top of Tržiště ulice in mid-1917, after moving from Zlatá ulička, or Golden Lane. The U.S. Embassy and consular office now occupy this prime location. Although security is stepped down compared with a few years ago, the many police, guards, and jersey barriers don’t offer much of an invitation to linger.  Tržiště 15, at Vlašská, Malá Strana

Tržiště 15, at Vlašská, Malá Strana

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Velkopřevorské náměstí

(Grand Priory Square

). This square is south and slightly west of the Charles Bridge, next to the Čertovka stream. The Grand Prior’s Palace fronting the square is considered one of the finest baroque buildings in the Lesser Quarter, though it’s now part of the

Embassy of the Sovereign Military Order of Malta—the contemporary (and very real) descendants of the Knights of Malta. Alas, it’s closed to the public. Opposite is the flamboyant orange-and-white stucco façade of the Buquoy Palace, built in 1719 by Giovanni Santini and the present home of the French Embassy. The so-called John Lennon Peace Wall,

leading to a bridge over the Čertovka, was once a kind of monument to youthful rebellion, emblazoned with a large painted head of the former Beatle. But Lennon’s visage is seldom seen these days; the wall is usually covered instead with political and music-related graffiti.  Velkopřevorské náměstí, Malá Strana

Velkopřevorské náměstí, Malá Strana

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 12, 20, or 22

.

Vojanovy sady

FAMILY

(Vojan Park

). Once the gardens of the Monastery of the Discalced Carmelites, later taken over by the Order of the English Virgins, this walled garden is now part of the Ministry of Finance. With its weeping willows, fruit trees, and benches, it provides another peaceful haven in summer. Exhibitions of modern sculpture are occasionally held here, contrasting sharply with the two baroque chapels and the graceful Ignaz Platzer statue of John of Nepomuk standing on a fish at the entrance. At the other end of the park you can find a terrace with a formal rose garden and a pair of peacocks that like to aggressively preen for visitors under the trellises. The park is surrounded by the high walls of the old monastery and new Ministry of Finance buildings, with only an occasional glimpse of a tower or spire to remind you of the world beyond.  U lužického semináře 17, between Letenská ulice and Míšeňská ulice, Malá Strana

U lužického semináře 17, between Letenská ulice and Míšeňská ulice, Malá Strana

www.vojanovysady.cz

www.vojanovysady.cz

Line A: Malostranská

.

Line A: Malostranská

.

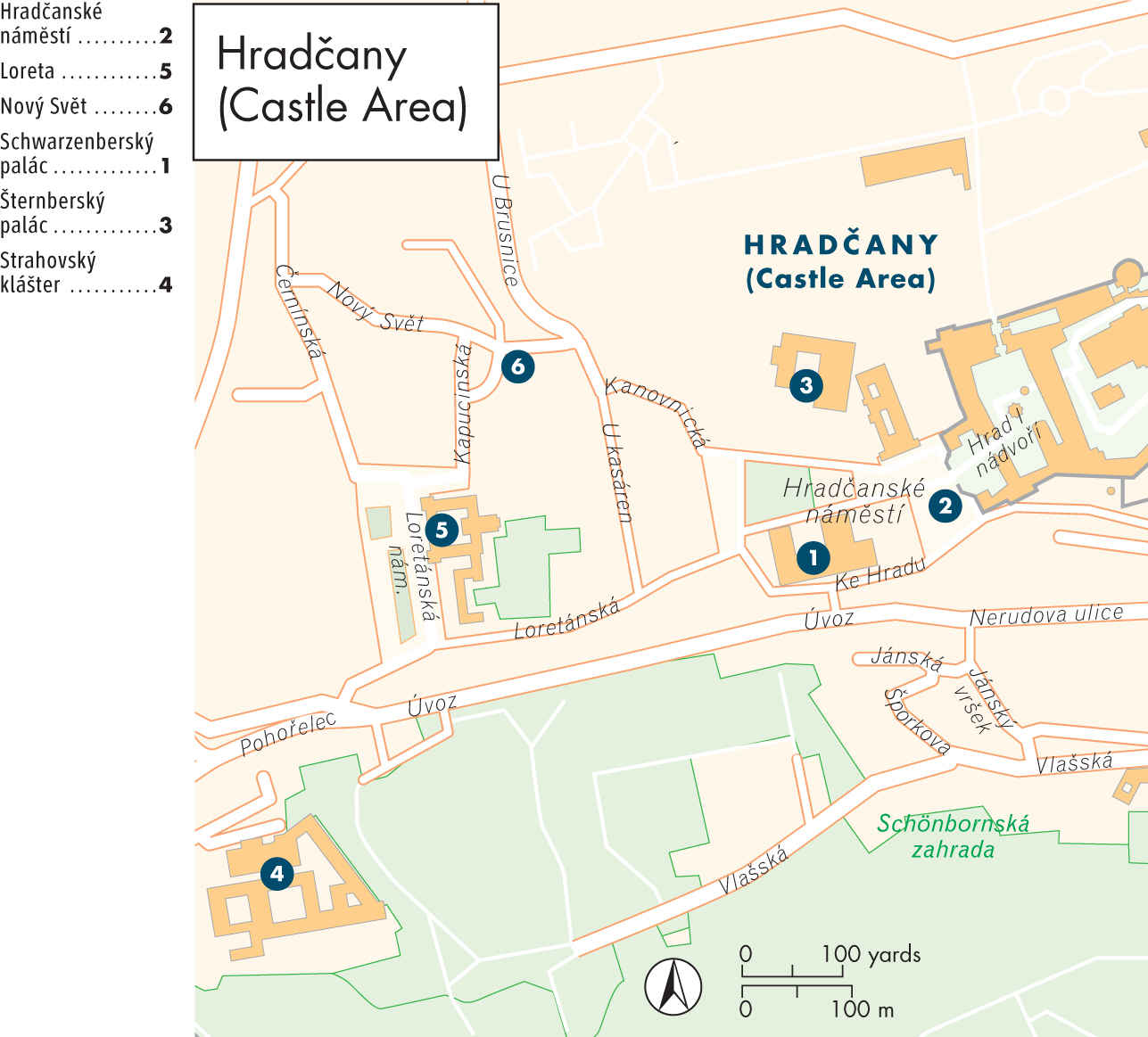

HRADČANY (CASTLE AREA)

To the west of Prague Castle is the residential Hradčany (Castle Area), a town that during the early 14th century emerged from a collection of monasteries and churches. The concentration of history packed into Prague Castle and Hradčany challenges those not versed in the ups and downs of Bohemian kings, religious uprisings, wars, and oppression—but there’s no shame in taking it all in on a purely aesthetic level.

GETTING HERE AND AROUND

There’s a rise from river level of nearly 1,300 vertical feet to get to the Castle Area, so if you’re on foot, be prepared for a climb. The best Metro approach is via Line A. ■ TIP → Don’t get off at the Hradčanská stop (as the name might imply). Instead, take the metro to Malostranská, and after exiting the station, take Tram No. 22 running north (uphill) to the stop Pražský hrad (Prague Castle). The tram leaves you about 200 yards north of the Castle.

TIMING

To do justice to the subtle charms of Hradčany once you arrive, allow at least two hours just for ambling and admiring the passing buildings and views of the city. The Strahovský klášter halls need about a half hour to take in, more if you tour the small picture gallery there, and the Loreta and its treasures need an equal length of time at least. The Národní galerie in the Šternberský palác deserves a minimum of a couple of hours. Keep in mind that several places are not open on Monday, and that early morning is the least crowded time to visit.

TOP ATTRACTIONS

Hradčanské náměstí

(Hradčany Square

). With its fabulous mixture of baroque and Renaissance houses, topped by the Castle itself, this square had a prominent role in the film Amadeus

(as a substitute for Vienna). Czech director Miloš Forman used the house at No. 7 for Mozart’s residence, where the composer was haunted by the masked figure he thought was his father. The flamboyant rococo Arcibiskupský palác (Archbishop’s Palace), on the left as you face the Castle, was the Viennese archbishop’s palace. For a brief time after World War II, No. 11 was home to a little girl named Marie Jana Korbelová, better known as former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.  Hradčanské náměstí, Hradcany

Hradčanské náměstí, Hradcany

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Schwarzenberský palác

(Schwarzenberg Palace

). A boxy palace with an extravagant façade, this space is home to the National Gallery’s permanent exhibition of baroque sculpture and paintings. Among the masters featured are Peter Brandl, Maximilian Brokof, and the sculptor Mathias Braun (whose work you’ve seen on the Charles Bridge). With arched ceilings and displays on how artists worked and what their studios were like during the baroque period, the Schwarzenberg interior is every bit as exuberant as the outside, and its hushed vibe might provide just the antidote to those tourist hordes outside.  Hradčanské nám. 2, Hradcany

Hradčanské nám. 2, Hradcany

233–081–713

233–081–713

www.ngprague.cz

www.ngprague.cz

300 Kč

300 Kč

Closed Mon.

Closed Mon.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Šternberský palác

(Sternberg Palace

). The 18th-century Šternberský palác houses the National Gallery’s collection of antiquities and paintings by European masters from the 14th to the 18th century. Holdings include impressive works by El Greco, Rubens, and Rembrandt.  Hradčanské nám. 15, Hradcany

Hradčanské nám. 15, Hradcany

233–090–570

233–090–570

www.ngprague.cz

www.ngprague.cz

300 Kč

300 Kč

Closed Mon.

Closed Mon.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

WORTH NOTING

Loreta

(Loreto Church

). The seductive lines of this church were a conscious move on the part of Counter-Reformation Jesuits in the 17th century, who wanted to build up the cult of Mary and attract Protestant Bohemians back to the fold. According to legend, angels had carried Mary’s house from Nazareth and dropped it in a patch of laurel trees in Ancona, Italy. Known as Loreto (from the Latin for “laurel”), it immediately became a destination of pilgrimage. The Prague Loreto was one of many symbolic reenactments of this scene across Europe, and it worked: Pilgrims came in droves. The graceful façade, with its voluptuous tower, was built in 1720 by the ubiquitous Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer, the architect of the two St. Nicholas churches in Prague.  Loretánské nám. 7, Hradcany

Loretánské nám. 7, Hradcany

220–516–740

220–516–740

www.loreta.cz

www.loreta.cz

150 Kč

150 Kč

Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Nový Svět.

This picturesque, winding little alley, with façades from the 17th and 18th centuries, once housed Prague’s poorest residents, but now many of the homes are used as artists’ studios. The last house on the street, No. 1, was the home of the Danish-born astronomer Tycho

Brahe. Supposedly Tycho was constantly disturbed during his nightly stargazing by the neighboring Loreto’s church bells. He ended up complaining to his patron, Emperor Rudolf II, who instructed the Capuchin monks to finish their services before the first star appeared in the sky.  Nový Svět, Hradcany

Nový Svět, Hradcany

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22

.

Strahovský klášter

(Strahov Monastery

). Founded by the Premonstratensian order in 1140, the monastery remained theirs until 1952, when the communists suppressed all religious orders and turned the entire complex into the Památník národního písemnictví

(Museum of National Literature). The major building of interest is the Strahov Library,

with its collection of early Czech manuscripts, the 10th-century Strahov New Testament, and the collected works of famed Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe. Also of note is the late-18th-century Philosophical Hall.

Its ceilings are engulfed in a startling sky-blue fresco that depicts an unusual cast of characters, including Socrates’ nagging wife Xanthippe; Greek astronomer Thales, with his trusty telescope; and a collection of Greek philosophers mingling with Descartes, Diderot, and Voltaire.  Strahovské nádvoří 1, Hradcany

Strahovské nádvoří 1, Hradcany

233–107–704

233–107–704

www.strahovskyklaster.cz

www.strahovskyklaster.cz

80 Kč library

80 Kč library

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22 to Pohořelec

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22 to Pohořelec

.

PRAŽSKÝ HRAD (PRAGUE CASTLE)

Despite its monolithic presence, Prague Castle is not a single structure but a collection of structures dating from the 10th to the 20th centuries, all linked by internal courtyards. The most important are the cathedral, the Chrám svatého Víta, clearly visible soaring above the castle walls, and the Starý Královský palác, the official residence of kings and presidents and still the center of political power in the Czech Republic.

GETTING HERE AND AROUND

As with the neighboring environs, the best public transportation here is via Metro Line A to Malostranská and then continuing onward with Tram No. 22. Taxis work, too, of course, but they can be expensive. The Castle is compact and easily navigated. But be forewarned: the Castle, especially Chrám svatého Víta, teems with huge crowds practically year-round.

TIMING

The Castle is at its best in early morning and late evening, when it holds an air of mystery. (It’s incomparably beautiful when it snows.) The cathedral deserves an hour—but budget more time, as the number of visitors allowed inside is limited and the lines can be long. Another hour should be spent in the Starý Královský palác, and you can easily spend an entire day taking in the museums, the views of the city, and the hidden nooks of the Castle.

VISITOR INFORMATION

Informační středisko

(Castle Information Office

). This is the place to come for entrance tickets, guided tours, audio guides with headphones, and tickets to cultural events held at the castle. You can wander around the castle grounds, including many of the gardens, for free, but to enter any of the historic buildings, including St. Vitus’s Cathedral, requires a

combined-entry ticket (valid for two days). There are two ticket options. The “Short Visit” (cheaper option) allows entry to St. Vitus’s Cathedral, the Old Royal Palace, Golden Lane, St. George’s Basilica, and Daliborka Tower. This will provide more than enough quality time in the castle. The more expensive “Long Visit” also includes entry to a permanent exhibition on the history of the castle called The Story of Prague Castle

and to the Powder Tower. If you just want to walk through the castle grounds, note that the gates close at midnight from April through October and at 11 pm the rest of the year, and the gardens are open from April through October only.  Třetí nádvoří, across from entrance to St. Vitus’s Cathedral, Pražský Hrad

Třetí nádvoří, across from entrance to St. Vitus’s Cathedral, Pražský Hrad

224–372–423

224–372–423

www.hrad.cz

www.hrad.cz

Long visit 350 Kč, short visit 250 Kč, The Story of Prague Castle exhibit 140 Kč, Picture Gallery 100 Kč, Powder Tower 70 Kč, photo fee 50 Kč, audio guide 350 Kč (3 hrs)

Long visit 350 Kč, short visit 250 Kč, The Story of Prague Castle exhibit 140 Kč, Picture Gallery 100 Kč, Powder Tower 70 Kč, photo fee 50 Kč, audio guide 350 Kč (3 hrs)

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22 to Pražský Hrad

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22 to Pražský Hrad

.

TOP ATTRACTIONS

Bazilika svatého Jiří

(St. George’s Basilica

). Inside, this church looks more or less as it did in the 12th century; it’s the best-preserved Romanesque relic in the country. The effect is at once barnlike and peaceful, as the warm golden yellow of the stone walls and the small arched windows exude a sense of enduring harmony. Prince Vratislav I originally built it in the 10th century, though only the foundations remain from that time. The father of Prince Wenceslas (of Christmas carol fame) dedicated it to St. George (of dragon fame), a figure supposedly more agreeable to the still largely pagan people. The outside was remodeled during early baroque times, although the striking rusty-red color is in keeping with the look of the Romanesque edifice. The painted, house-shape tomb at the front of the church holds Vratislav’s remains. Up the steps, in a chapel to the right, is the tomb Peter Parler designed for St. Ludmila, grandmother of St. Wenceslas.  Nám. U sv. Jiří, Pražský Hrad

Nám. U sv. Jiří, Pražský Hrad

224–372–434

224–372–434

www.hrad.cz

www.hrad.cz

Included in 2-day castle ticket (250 Kč–350 Kč)

Included in 2-day castle ticket (250 Kč–350 Kč)

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22 to Pražský Hrad

.

Line A: Malostranská plus Tram No. 22 to Pražský Hrad

.

Fodor’s

Choice

Chrám svatého Víta

(St. Vitus’s Cathedral

). With its graceful, soaring towers, this Gothic cathedral—among the most beautiful in Europe—is the spiritual heart of Prague Castle and of the Czech Republic itself. The cathedral has a long and complicated history, beginning in the 10th century and continuing to its completion in 1929. Note that it’s no longer free to enter the cathedral (entry is included in the combined ticket to see the main castle sights). It’s perfectly okay just to wander around inside and gawk at the splendor, but you’ll get much more out of the visit with the audio guide, which is available at the castle information center.

Chrám svatého Víta

(St. Vitus’s Cathedral

). With its graceful, soaring towers, this Gothic cathedral—among the most beautiful in Europe—is the spiritual heart of Prague Castle and of the Czech Republic itself. The cathedral has a long and complicated history, beginning in the 10th century and continuing to its completion in 1929. Note that it’s no longer free to enter the cathedral (entry is included in the combined ticket to see the main castle sights). It’s perfectly okay just to wander around inside and gawk at the splendor, but you’ll get much more out of the visit with the audio guide, which is available at the castle information center.

Once you enter the cathedral, pause to take in the vast but delicate beauty of the Gothic and neo-Gothic interior. Colorful light filters through the brilliant stained-glass windows. This western third of the structure, including the façade and the two towers you can see from outside, was not completed until 1929, following the initiative of the Union for the Completion of the Cathedral. Don’t let the neo-Gothic illusion keep you from examining this new section. The six stained-glass windows to your left and right and the large rose window behind are modern masterpieces. Take a good look at the third window up on the left. The familiar art nouveau flamboyance, depicting the blessing of Sts. Cyril and Methodius (9th-century missionaries to the Slavs), is the work of Alfons Mucha, the Czech founder of the style. He achieved the subtle coloring by painting rather than staining the glass.

Walking halfway up the right-hand aisle, you will find the Svatováclavská kaple (Chapel of St. Wenceslas). With a tomb holding the saint’s remains, walls covered in semiprecious stones, and paintings depicting the life of Wenceslas, this square chapel is the ancient core of the cathedral. Stylistically, it represents a high point of the dense, richly decorated—though rather gloomy—Gothic favored by Charles IV and his successors. Wenceslas (the “good king” of the Christmas carol) was a determined Christian in an era of widespread paganism. Around 925, as prince of Bohemia, he founded a rotunda church dedicated to St. Vitus on this site. But the prince’s brother, Boleslav, was impatient to take power, and he ambushed and killed Wenceslas in 935 near a church at Stará Boleslav, northeast of Prague. Wenceslas was originally buried in that church, but so many miracles happened at his grave that he rapidly became a symbol of piety for the common people, something that greatly irritated the new Prince Boleslav. Boleslav was finally forced to honor his brother by reburying the body in the St. Vitus Rotunda. Shortly afterward, Wenceslas was canonized.

The rotunda was replaced by a Romanesque basilica in the late 11th century. Work began on the existing building in 1344. For the first few years the chief architect was the Frenchman Mathias d’Arras, but after his death in 1352 the work continued under the direction of 22-year-old German architect Peter Parler, who went on to build the Charles Bridge and many other Prague treasures.

The small door in the back of the chapel leads to the Korunní komora (Crown Chamber), the Bohemian crown jewels’ repository. It remains locked with seven keys held by seven important people (including the president) and rarely opens to the public.