July 1865 found some of New York’s wealthiest citizens joining an eclectic collection of gamblers, horsemen, and social hangers-on in the daily rounds of mineral baths and Thoroughbred racing at Saratoga Springs, New York. The Civil War had ended only three months previously, and most of those visiting this Adirondack resort sought to put all lingering thoughts of the war behind them. If they had entertained any thoughts at all of this late war, they had viewed it as an opportunity to make vast sums of money or, at worst, as a period of unpleasant news reports. Saratoga visitors quickly turned their thoughts to much more pleasant prospects lying ahead. What lay most immediately ahead was a showdown between two outstanding Thoroughbreds, one called Kentucky and the other Asteroid.

Kentucky’s color was a rich and lustrous bay. His mahogany-hued body shone with a dark glean, in striking contrast to the white hair extending upward from his hoof halfway to the knee on his right front leg. A white stripe ran the length of his face, narrowing toward his nose. His tail had been cropped straight across in the English fashion, about four inches above the hock. He had two white marks on his back caused by wear from the saddle. Kentucky stood not hugely tall at only fifteen and a half hands—a little more than five feet at the withers where his shoulder blades came together. But people weren’t looking at his height when they studied the fire in his eye and the strength in his limbs.1

A son of the prolific Lexington, a breeding stallion who reigned as the most successful sire of American Thoroughbreds, Kentucky had come into the hands of a triumvirate of wealthy men in the Northeast soon after his Bluegrass breeder, John Clay, took the colt to the track at Paterson, New Jersey, to sell in 1863. The track at Paterson had opened its gates for the first time that year and stood at the forefront of a revival of racing in the North, a revival that undoubtedly delighted wealthy sportsmen of New York. Interest among them in Thoroughbred horse racing had reignited with a spark that by the end of the war would erupt into a roaring flame. This represented a huge change in the future course of racing in the North. For close to twenty years, the Northeast had existed without any Thoroughbred racing, at least without any racing of consequence organized by jockey clubs. Melvin Adelman has written in a history of New York sports: “By 1845 horse racing in New York was in a state of virtual collapse…. For the next twenty years the sport floundered.” Men whose fortunes had expanded exponentially during the war were among those eager to take up the sport, in a desire to show off their new wealth.2

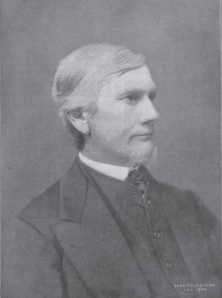

Kentucky was of a rich bay color, one in a triumvirate of talented sons of Lexington, all foaled in 1861 in the Bluegrass. Kentucky’s dam was Magnolia, a daughter of the imported sire Glencoe. John Clay, a son of Henry Clay, bred Kentucky. Magnolia was among the highly prized Thoroughbreds that once belonged to Henry Clay. (W. S. Vosburgh, Racing in America, 1866–1921 [New York: Scribner Press, 1922], facing 70.)

Clay, taking racehorses with him to Paterson to sell in 1863, was among a vast number of Kentuckians who had chosen not to fight in the war. Throughout the war, he lent his energies to his business, which was the breeding, raising, racing, and selling of Thoroughbreds. Choosing not to enlist did not mean that he remained unaffected by wartime strife, however. On account of the war, the amount of horse racing declined throughout the South and in the border state of Kentucky, and, thus, Clay would have faced a greatly diminished market for the sale of his racing stock. He had three options. The first was to stay home and race the colt called Kentucky in Lexington, where the sport managed to stumble along throughout the war. The only occasion when the club in Lexington did not hold a race meet was during the spring of 1861, when racing shut down after the first day owing to military maneuvers held close by. The second option was to take his horses to New Orleans to race, if he thought the journey safe, which it probably was not. The final option was the choice a number of Kentuckians had made: take their stables to race in the North, where they would, it was presumed, be safer from wartime hostilities.3

The Kentuckians Zeb Ward, Clay, Captain T. G. Moore, and Dr. J. W. Weldon campaigned their racing stables in Pennsylvania and on Long Island at New York’s old Union Course in 1862. They also raced in Boston. Back in the Bluegrass, Kentuckians who had not shipped their horses to the Northeast were beginning to see them impressed for army duty or stolen by guerrillas and outlaws. Bluegrass breeders lost untold numbers of bloodstock this way, for this war that began in an effort to save the Union and wound up as a war to end slavery “did much to interfere both with breeding and racing in Kentucky,” as the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder observed. Edward Hotaling likewise has observed: “Kentucky [horsemen] had to look northward for buyers, tracks, and safe havens for their stables. The scene was bleak.”4

However bleak the racing outlook might have appeared throughout the South and in Kentucky, interest in sports was on the rise in New Jersey and New York. Northern racing experienced a rebirth during these war years, just as other modern sports also began to attract urban crowds. In fact, it was not unusual for New Yorkers to attend athletic events as spectators despite the war, even when the war entered their midst. This happened around the time of the draft riots in Manhattan in 1863. Some 105 persons, many of them Irish, rioted over four days in mid-July of that year because they resented the fact that they could not buy their way out of military service as the wealthy could. However, some five thousand New Yorkers had forgotten the riots by July 22. They boarded ferries to attend a championship baseball game at Elysian Fields at Hoboken in New Jersey. New York lost the game to Brooklyn, 10–9.5

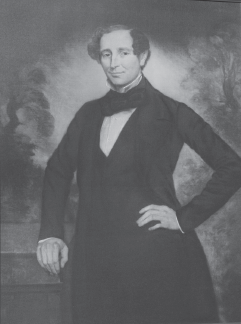

John Clay, a Bluegrass horse trainer and breeder, was a son of Henry Clay, whose exemplary career in politics earned him the nickname the Great Compromiser. John Clay inherited his father’s Thoroughbred breeding operations and continued them on a portion of Ashland, the family estate in Lexington. (Turf, Field and Farm 66, no. 11 [March 18, 1898]: 345.)

During that same summer, from July 1 through July 3, the Battle of Gettysburg took place in the nearby state of Pennsylvania. Some forty-six to fifty-one thousand Americans died over three days of fighting in and surrounding this small town, ending the South’s second invasion of the North under General Robert E. Lee. Gettysburg, in fact, acquired notoriety as the battle having the greatest number of Civil War casualties. Four and a half months later, in November, President Abraham Lincoln redefined the purpose of the war with his Gettysburg Address, shaping its new framework into a mission to end slavery. Despite the battles, despite the redefined purpose of the war, nothing was stopping the rebirth of racing in the Northeast. A month following the Battle of Gettysburg, Northern sportsmen inaugurated Thoroughbred racing at Saratoga Springs. “Where did anyone ever get the idea that racing had stopped at Saratoga in wartime?” Landon Manning asked rhetorically when writing his history of trotting and Thoroughbred racing at Saratoga Springs. The answer stood the same as it did downstate, when New Yorkers boarded ferries to watch the baseball game at Elysian Fields.6

By the time of the inaugural race meet at Saratoga Springs, Clay had raced and won with his colt Kentucky at the Paterson track in New Jersey. This caught the attention of the well-regarded sportsman John F. Purdy. Purdy was a wine dealer, a “gentleman” jockey (which meant that he did not pursue a living riding racehorses), and a man whose advice people in racing held in high regard. He promptly bought the colt for $6,000, taking him in a package deal with a filly named Arcola. Clay had insisted that Purdy purchase Arcola as part of the sale, but Purdy’s interest had been entirely in Kentucky.7

Purdy pronounced Kentucky the most magnificent two-year-old colt he had ever seen. As well, he announced that he was buying Kentucky, not for himself, but for all New York, a development that indicated the rising interest in horse racing in that state. What Purdy really might have meant to say was that he was acting as a sales agent for wealthy buyers. The next time Kentucky appeared on the racecourse, which was the following spring (1864), when he was three years old, he raced under the colors of an elite group that included William R. Travers, John Hunter, and George Osgood. This group brought much attention to itself that same year for being among the founders of a new racecourse at Saratoga Springs. The group had assumed control of racing at Saratoga in 1863 and opened a new grandstand and racecourse across the road from the primitive racing grounds where the inaugural 1863 meet had raced. Purdy served as the new Saratoga track’s vice president and Travers as its president.8

Travers and Hunter were well known beyond the racecourse at Saratoga Springs. In fact, they were better known as Wall Street speculators who had realized remarkable success with buying and selling equities. Under the firm name of Travers and Jerome, Travers and his Wall Street partner, Leonard Jerome (the latter destined to be Winston Churchill’s grandfather), had notoriously run up a $50,000 capital investment in 1856 to a sum larger than $1 million three years later. This seems even more remarkable for the clear profit it produced, as the partners had pulled off their financial coup during an era when personal income tax did not exist. By 1864, Travers and Jerome had expanded their involvement in horse racing into building racecourses, beginning in 1864 with Saratoga Springs. Jerome would open a course in 1867 with much more lavish facilities in Westchester County, closer to the city of New York. He called his swank new track Jerome Park.9

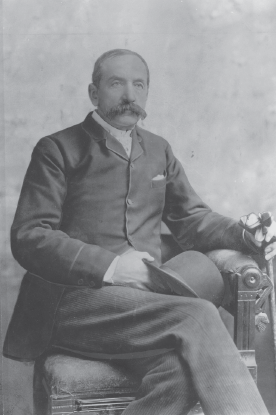

William R. Travers served as the first president of the new Saratoga Race Course, opened in 1864. He also was a partner in the ownership of the horse Kentucky, purchased from John Clay of Lexington. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library.)

Two years later, by the summer of 1865, when the war was over, Kentucky had run up a remarkable record. Although he had suffered his only career loss in 1864 in the Jersey Derby at Paterson (where he ran third—fourth according to some reports—behind another son of Lexington called Norfolk), Kentucky had strung together a winning streak that included the Jersey St. Leger Stakes, the Sequel Stakes, and a match race—a one-on-one contest against one other horse. All that remained for him to do if he were to secure a place as champion over all other American racehorses was to race against the third member of Lexington’s great sons who were all born in 1861. This was the colt named Asteroid, who, like Kentucky and Norfolk, was bred in the Bluegrass.

Asteroid was also bay. He and Kentucky both were four years old, born the year the Civil War broke out. Asteroid, unlike Kentucky, had never known defeat on the racecourse. This might have seemed to make him the champion of American racehorses, for Kentucky, his only equal, had lost one race. Later, at the close of his career, Kentucky would also lose a race against the clock when he attempted to beat the timed record of his sire, Lexington. But Asteroid had accumulated an unblemished record, even if he had raced entirely in Ohio and the border states of Kentucky and Missouri, a geographic happenstance that New Yorkers imperiously viewed as parochial.

Asteroid had also proved his speed and endurance in quite another way. He had survived a devil of a gallop at the hands of outlaws disguised as Union soldiers who had taken him during a raid on Woodburn Farm, in the heart of horse country. “Mr. Alexander and his family were just sitting down to dinner … when an old negro woman came running in with the news that there was a great commotion at the stables, a party of men being engaged in seizing and carrying off the horses,” read one account. The theft had occurred quite brazenly, in the middle of the day.10

The theft took place during the autumn of 1864, six months before the war ended. The outlaw riding Asteroid had forced him to swim across the Kentucky River under a hail of bullets fired their way. Asteroid wound up ransomed for Woodburn Farm and was back at the races in the spring of 1865, with people in the Northeast calling for him to race against Kentucky. This challenge certainly was taking everyone’s mind off the late war, as the prospect of a widely anticipated race between the two posed all kinds of intriguing possibilities.

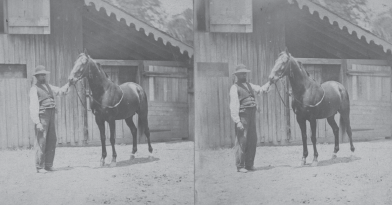

Asteroid, another of Lexington’s famous offspring (his dam was Nebula, a daughter of the imported Glencoe), raced for his owner, Robert Aitcheson Alexander, of Woodburn Farm in Woodford County, Kentucky. Outlaws stole the horse during the Civil War. Alexander’s friends ransomed him and returned him to Alexander. Asteroid then resumed his racing career. He was undefeated on the racetrack, winning twelve races and a total of $12,800. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library.)

With Asteroid having defeated all his competition west of the Allegheny Mountains, it seemed a shame to many patrons of the sport that he had never gone east to race against Kentucky. As people in the Northeast saw it, a showdown of this sort would settle the matter of which colt was the better of the two and, therefore, the fastest racehorse in the United States. But people also looked for something more than a horse race in this challenge issued to Asteroid. Sectional rivalries lingered after the war, and these two horses had acquired the status of sectional rivals. General Ulysses Grant and his Confederate counterpart, General Robert E. Lee, had barely signed the terms of peace in April 1865 at Appomattox Courthouse in Virginia when New York’s wealthy sportsmen had begun to anticipate still another sectional confrontation, this one to occur on the racecourse. There seemed no better way to reassert the North’s victory in the war.

None could hide their feelings about this event: the rivalry between these two horses stirred up “a little unpleasant feeling between men of different sections,” according to the recollections of the era’s turf authority, Hamilton Busbey. This highly anticipated showdown was “marked with much feeling, and the names of the two horses were daily in the mouths of thousands,” Busbey wrote. Ironically, although these horses represented sectional rivalries, their coming together on the racecourse was also expected to signal sectional healing. Busbey suggested that the sport of horse racing had already demonstrated healing qualities because “men who, a few months before, had faced each other on the battle-field, stood side by side on the race-course, enthusiastically applauding the silken-coated thoroughbreds.”11

Sportsmen sensed another irony in the challenge. They might have seen this confrontation not so much as between North and South, as the war had been fought, as between West and East, the latter being where the locus of power in horse racing had shifted immediately after the Civil War. The West, during this era, meant Kentucky—and every other place on the map to the left of the Allegheny Mountains. While the power in racing had, indeed, shifted east, Kentucky no more than Virginia or Pennsylvania actually occupied a geographic position that could be described as in the West. This geographic designation, though it held ominous meaning for horse racing, was at the same time misleading.

Kentucky’s historic moment at the edge of the Western frontier had passed decades earlier in the relentless push Americans had made from the East Coast toward the Pacific Ocean. Nonetheless, sporting men of New York continued until the twentieth century, almost one hundred years later, to refer to Kentucky horse racing as situated in the West. They had their reasons, which might have been mostly chauvinistic. New York viewed itself as superior to a rough-and-ready Kentucky situated on the fringes of American society. The terms East and West denoted power, and for decades after the war, a power struggle ensued between New Yorkers and Kentuckians over control of Thoroughbred racing. For reasons not quite clear, however, Kentuckians placidly accepted the characterization of their racing as Western and unfolding on a mythical frontier. Never during the latter part of the nineteenth century did Bluegrass Kentuckians attempt to discourage the use of this designation by insisting that their racing was Southern. So it remained Western. The Kentucky Derby, in the years following its 1875 inauguration, became known as the great race of the Western states.

Any sectional showdown between Kentucky and Asteroid consequently would carry the weight of this social and political divide. The way Northeastern patrons of horse racing regarded Asteroid illustrated precisely how they considered their side of the divide superior to the West. Although racing’s patrons in New York and New Jersey acknowledged Asteroid as the “bright star of the West,” never did they accord him the recognition they probably should have. Never did they call him the bright star of all the turf. They had planned to bestow that kingly moniker on Kentucky.12

Northeastern patrons had placed all their support with their horse, despite the irony that he bore the name of his home state, Kentucky, the same place Asteroid came from. And how they loved to watch their horse race. Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, published in New York, paid homage to Kentucky as though this Thoroughbred were king of the animal kingdom. Wilkes’ Spirit and the public had fallen so deeply under his spell that they overlooked the nagging fact that he had a blemished race record while Asteroid’s record remained perfect. Obscuring reality, they thought of Kentucky as though he were the champion, when the two horses had never met.

The attention paid Kentucky by Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times was going far in boosting his popularity in the Northeast. The magazine’s editor, George Wilkes, weighted his news columns in favor of Kentucky, giving scant coverage to Asteroid. Wilkes was pro-Unionist, anti-Southern, and a chauvinistic New Yorker of the boldest stripe, all of which translated to a man suspicious of the state of Kentucky, which, although officially loyal to the United States, had sent soldiers to both sides during the war. Wilkes had more than a political ax swinging in favor of the horse Kentucky. He and Kentucky’s owners wanted to see the highly anticipated showdown between the two colts take place nowhere else but at that summer place of decadence, Saratoga Springs.13

Pleasure seekers had been coming to Saratoga Springs for decades, fondly referring to this little village as “the queen of watering places.” Since the Battle of Burgoyne during the Revolutionary War, Americans had recognized this fancy watering hole for its mineral springs, which were believed beneficial to one’s health. Saratoga Springs also proved popular for quite another reason, however, as the scene of wide-open gambling, a favorite pastime of the elite class of visitors. This elite class had turned Saratoga Springs into the social centerpiece of the summer season, deeming it the proper place for an annual reunion of the wealthy and the famous. The village was the place to see and be seen, as gamblers and social and political leaders all realized. From 1863 on, Saratoga Springs also developed into the summertime place to thrill to the sight of fast Thoroughbreds competing on the racecourse. The racetrack scenes and those along the main thoroughfare of the village stood out as ostentatious demonstrations of excessive wealth.14

John Morrissey introduced Thoroughbred racing to Saratoga Springs in 1863. The following year, William R. Travers led the group of capitalists that opened a new racecourse, the Saratoga Race Course, across the road from the old. Racing continues on that site to this day. (Harper’s Weekly 9, no. 557 [August 24, 1867]: 541.)

“Saratoga’s Broadway was a canyon flanked by magnificent elms and gargantuan hotels and jammed with men in expensive black broadcloth and women in the latest fashions,” writes Edward Hotaling, describing the nightly promenades through the heart of the village. New Yorkers who participated in this annual migration upstate by steamboat or rail brought their servants, their children, their fancy dogs, and their racing stables to escape the oppressive heat and foul odors that they had no wish to endure in the sweltering city of New York. As these folk saw it, Saratoga existed as their private garden, their escape from the worrisome burdens of urban life.15

The carefree lifestyle in Saratoga reflected the prevailing mood among the Springs’s summer residents during those months when the United States emerged from its civil war. No longer obliged to consider even remotely the dour topic of battles fought and Americans dying, summer visitors in 1865 turned their full attention to the training progress of Kentucky and Asteroid. Although the intended race was not to occur until August, advance betting had begun at the Cincinnati, Ohio, races in June.16

The race for the Saratoga Cup decidedly was building into much more than a showdown between these horses. As June turned into July, the event did, indeed, appear to be turning into a power struggle between New Yorkers and the old guard of rural Bluegrass Kentucky. A racing periodical would editorialize two years later that “the American turf—at least so far as New York, the capital, is concerned—has ceased to be provincial and has become metropolitan.” Contemporaries could see this beginning to unfold in 1865. The result would greatly affect the position of the Bluegrass in the new, postwar world of horse racing, for it compromised the stranglehold that Kentucky landowners once had held over the sport.17

The war years had altered much about power relations in the United States, and now, it seemed, horse racing was poised to take its turn at this wheel of change. Racing in the Northeastern cities was experiencing a resurgence because men of old money along with those whose wealth had grown exponentially during the Civil War had taken control of the sport. They did so by default, the sport having collapsed in much of the South. And they did so simply by exerting the power of their wealth, building their own racecourses in New York. People referred deferentially to this elite class as “the substantial men of the day … some of the most respectable men,” as though paying obeisance to their wealth and social standing.18

The wheel of change did not stop at the new racecourses constructed in the Northeast. In a short while, horse breeders in New York and New Jersey would challenge the claim of Bluegrass Kentucky as the cradle of the racehorse. Hanging in the balance was the livelihood of Bluegrass horsemen and, with this, the economy of central Kentucky. If the breeding of racehorses no longer centered in full strength on the Bluegrass, Kentuckians would lose the full potential of this livelihood, and all in the local community would feel the effects. And horse breeding was emerging as a livelihood: few breeders in Kentucky possessed the wealth of Robert Aitcheson Alexander, owner of Woodburn Farm. Alexander alone could stand on a par with the new money coming into the sport because he was not dependent on farming or horse breeding for a living. Like many in the Northeast, his money came from outside the realm of agriculture, from his ironworks in Scotland and Kentucky.19

The power struggle emerging in Thoroughbred racing did, in fact, mirror the shifts in power occurring at all levels of American economy and life. More people were moving to the Northern cities. More immigrants were arriving on American shores. Increasing industrialization was bringing expanded wealth to the elite class among industrialists and financial brokers living in these Northern cities. Industrialization was creating a sea change in demographics because the major portion of wealth no longer lay in the South or in agricultural pursuits, including the breeding and raising of racehorses.

But, for this particular moment during the summer of 1865 at Saratoga Springs, the question of shifting economics and power narrowed down to which group was to control the breeding and racing of fast horses. Was the future to lie with the old guard in Kentucky (and also in Tennessee, where a class of gentry landowners pursued horse breeding on a smaller but highly successful scale) or with the new moguls of industry and finance in the Northeast? The power struggle to ensue would cut across a wide swath of American demographics, from wealthy New York capitalists to Bluegrass landowners, while also touching peripherally on the mountain folk of eastern Kentucky, who would constitute a convenient contrast to these other groups. The power struggle also would involve Kentucky’s African American community: the once dominant numbers of black jockeys and trainers who rode and trained many of these fast horses in Kentucky and also in New York.

This was a critical time for the future of Thoroughbred racing. The shift of power in the sport represented no small achievement to those New Yorkers who had lent their support to Thoroughbred racing, for the breeding industry had collapsed in that state following the economic Panic of 1837. New York’s breeding and racing activities had not recovered prior to the Civil War. The sport had been virtually dead in New York, stomped into oblivion first by the financial crisis and then by public sentiment opposed to gambling and racing. The Union Course on Long Island, once the site of well-attended races that brought together horses from the North and the South, had fallen into a disreputable state in which mule racing coexisted with what little Thoroughbred sport remained. One Thanksgiving Day, mules raced for a $50 purse that saw “eight of the obstinate brutes … brought to the starting point, … only four [of which] could be induced … to go anyhow.” Without a horse-breeding industry, racing in New York could not exist. The new, Northeastern turf moguls relied on Southerners to supply their sport with horses during the middle years of the Civil War until the resurgence of the sport in New York. New York sportsmen even had problems persuading the most reputable of their society to join in supporting the return of Thoroughbred racing, for the sport remained tainted with the unpopular specter of gambling.20

For at least ten years before the war, men of solid reputation in the Northeast had severed any connection they once might have had with the turf, owing to the sport’s disreputable notoriety. During this decade, individuals deemed unworthy by the elite class operated the tracks located in and around New York. Rather than see their names connected with these questionable entrepreneurs, wealthy sportsmen spurned racehorses and took up yachting.

Following the Panic of 1837, a second economic disaster occurred in 1857; this one affected not only the general welfare of Americans but also the health of the turf. The 1857 Panic exacerbated the decline of the turf because numbers of men who could afford to own racing stables experienced financial ruin. A nineteenth-century author, Lyman Weeks, observed that, on the eve of the Civil War, racing flourished only in Kentucky. Everywhere else, he wrote, the situation was grim: “Public interest in the turf had become reduced to a low point and the final clash of arms gave the sport what was feared at the time would be its death blow.”21

Thus, a handful of wealthy New Yorkers accomplished the near impossible when, partway through the war, they initiated a revival of Northern racing on bringing their good names and social reputations to the sport. Joining Travers, Hunter, Osgood, Jerome, and a few others in this effort was August Belmont, a titan of Fifth Avenue society and the founder of a bank in New York. Belmont was wealthy beyond the imaginings of the average Bluegrass horseman. He represented the archetypal capitalist of the Northeast—writ large. He took control of New York racing and soon become the virtual dictator of the American turf. His close friend Leonard Jerome, who made his money selling short in the stock market during the 1857 Panic, was already planning his elaborate racecourse, Jerome Park, on 250 acres known as the Bathgate estate that he had purchased in 1865 for $250,000 at Fordham, north of Manhattan. Belmont agreed to serve as the first president of the track.22

Powerful Northern men like these took Thoroughbred racing from regional popularity in the South to prominence as a national and commercialized sport. They made many changes, with the most radical being the way they converted a diversion of the Southern rural gentry into a major urban sport. They also changed the manner in which races were run. They followed the more recent English custom, replacing the old-style multiple heat racing with “dash” races in which a single trip around the track (or, perhaps, only a portion of the track) was all it took to determine the outcome of a race.

Heat racing, in which the horses returned to the track perhaps three more times following their first run to determine the outcome of an event, took all day to determine a winner. As Americans became more hurried in their lives, this change proved highly popular and helped boost the sport’s popularity in this country. No one, especially the new moguls of the business world, had time to while away an entire day waiting for horses to race one another into the ground over multiple heats to decide a race. That languid side of life had slipped away with the antebellum South.

Men like Belmont and Jerome were in a hurry, no different than other Americans. They were building fortunes and dynasties in their private lives. On the public front, they founded and ruled over lavish racecourses meant to complement the opulent breeding farms they were building in New York. These men determined the locations of the new racecourses, choosing places conveniently close to the city of New York, where they lived and worked. With lifestyles that differed so remarkably from the slower tempo of those of the antebellum planters of the South, these men were reshaping the sport to move to an upbeat pace.

These men might never have had the opportunity to seize this power had not the wartime interruption of racing and breeding in the slaveholding states forced the latter to surrender control of Thoroughbred racing and breeding. Control of the sport had swung back and forth between North and South in a cyclic pattern almost from the time racing began in the seventeenth century in the New World. However, the outcome of the Civil War left no doubt that the Northeast had regained the control that it had lost during the 1840s. This situation coincided with the rapidly rising popularity of this sport among men of means in New York: men like Travers and his group, which owned the racehorse Kentucky.

This showdown at Saratoga, then, really constituted more than a race between two horses. The cry that went up to see the horses race against each other appeared more like powerful New Yorkers stepping up to dictate where and how the sport should operate in this new world that emerged after the war. The race was looking more like an occasion for these new men in racing to show Bluegrass horsemen a thing or two about the sport that the Bluegrass and the South had so recently controlled. The rivalry between Asteroid and Kentucky fueled this power struggle and contributed directly to the revival of the sport in the North. “The fever spread, and the glory of the turf was revived in the North,” as one early history of Thoroughbred racing puts it.23

Before the war, Kentucky-bred horses had ruled the turf, sent via steamboats down the Ohio River to the Metairie course at New Orleans, where the greatest of them all, the horse named Lexington, had settled a regional rivalry on the racetrack. He had defeated his Mississippi rival, Lecomte, in a sectional contest on a par with any of the famous North-South contests held before the war in New York and the southern Atlantic states. Lexington retired from the track to a new career as a breeding stallion and, during the mid-1850s, came into the hands of the wealthiest breeder in Kentucky, Alexander, the squire of Woodburn Farm.

Here was a man who, despite living a solitary life in the country, never would have been mistaken for an individual of unsophisticated ways or means. A lifelong bachelor, Alexander was Kentucky born but a Cambridge-educated member of the British aristocracy who chose to return home to the Bluegrass. He also was the owner of Asteroid. Alexander had raised Asteroid on his grand estate in Kentucky’s Woodford County. As an agriculturist, he lived for the thrill and pride of breeding racehorses of Asteroid’s caliber. He could afford to pay a then-record $15,000 for Lexington to stand at stud at Woodburn because he possessed a fortune founded in industry and divested into agriculture and livestock breeding. Before the war, he had held more power than anyone in Kentucky breeding circles. If he felt this power in danger of slipping away soon after the war, he did not disclose this in any overt way. He seemed determined not to bow to the dictates of the new money emerging on the turf in the Northeast. Consequently, his initial reaction to challenges for a race against Kentucky was to ignore them.

Alexander’s disinterest in sending Asteroid to Saratoga began to come clear to Kentucky’s owners after their colt arrived at Saratoga— and Asteroid did not show up. Their reasons for insisting that the race take place at Saratoga and not farther west no doubt reflected the sense of power and control this group had begun to flex on the turf. Asteroid would have had to make a long journey by rail if Alexander were to send him to Saratoga. “Only he who has traveled with horses on a freight train can fully realize [the difficulties],” a Turf, Field and Farm contributor wrote during those years. “Journeys which require a day’s time on a passenger run, are of a week’s duration, and the jerkings of the inevitable stoppages and starts are enough to make every joint and muscle so sore that weeks are required to remedy the bad effects…. The animals are frequently thrown down or severely strained by their efforts to resist the shock.” Asteroid had raced in June at Cincinnati, winning twice, but no word had been heard of him since. Alexander remained aloof and silent, even as Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times initiated an assault in print on the squire of Woodburn for failing to put his horse on the train.24

The fiery and opinionated George Wilkes was as eager as Kentucky’s owners to see this race take place. He relied on all the power of his printing press to try to persuade Alexander to send Asteroid to Saratoga. Easterners had so highly anticipated this encounter that the Saratoga Race Course had sent a representative to Cincinnati during the races there in June to take advance wagers on the race. Kentucky’s owners had to save face, and in his editorials Wilkes revealed how closely aligned his interests were with these men. He began to goad, cajoling at first, then stepping up the tempo as the weeks went on.

Wilkes appealed to Alexander’s chivalry in trying to persuade him to put Asteroid on a train. “We should not like to be in Mr. Alexander’s shoes,” he wrote, “so far at least as the indignation of the ladies is concerned, if he should fail to bring his horse.” Wilkes might have intended his gentle nudge to sting more deeply than, at first glance, it would appear to, given that Alexander lived in a state bordering the South, where chivalry toward the ladies greatly mattered. Whatever his intentions, however, Wilkes failed to elicit a response from Alexander.25

Wilkes ramped up the tenor of his attack in a later edition, suggesting that Alexander “shirks the only opportunity he has ever had of measuring Asteroid against a horse of known merits and first-class reputation.” This statement might have stung even more deeply than the chivalric barb, for Western racing enthusiasts believed Asteroid to be the horse with the first-class reputation. He had never experienced defeat, while Kentucky had lost one race. So the question would have reverted to one of why Kentucky did not take a train west for a race.26

The barb with the greatest sting might have been the editor’s suggestion that Alexander simply was afraid to race Asteroid against Kentucky. Wilkes wrote that a man worth “millions of dollars, and who seems to believe in his horse should not have turned his back upon such an offer.” He added: “This is not the way to support the interests of the turf.” Alexander had profited from purchases that breeders made from his Woodburn Farm, according to Wilkes’ Spirit, and now, in turn, those breeders “are entitled to know which of these two rival stallions should be preferred as the stock horse of the future.” Wilkes was arguing that Alexander owed a debt of responsibility to the sport and, thus, needed to send Asteroid to Saratoga to meet Kentucky. By declining to race, Alexander was revealing his real intention: “to contribute nothing to racing in the North.”27

Late in July, Alexander found his voice. He sent a telegram directly to John Hunter, one of the triumvirate of Kentucky’s owners, agreeing to send out Asteroid against Kentucky—as long as Kentucky came west for two races: the first at Cincinnati and the second at Louisville, where Alexander was the leading force behind the Woodlawn Course. Like Kentucky’s owners, who operated the Saratoga course, Alexander shrewdly saw the effect on track attendance that this match would have. Thus, he insisted that one of these races take place at the track he supported, Woodlawn. He even offered to pay Kentucky’s travel expenses. “I think our tracks are as good as those in the east,” he wrote, adding: “A horse owned east of the Alleghenies will be as great a curiosity on a course in this section of country as one of my entries would be were he to appear to run for the Jersey Derby, St. Leger or Saratoga Cup.” He gave Kentucky’s owners until August 7 to respond.28

Hunter failed to respond directly, which irritated Alexander. “No doubt, he preferred to receive a proposition direct from Mr. Hunter,” remarked Alexander’s acquaintance, Sanders Bruce. Hunter’s spokesman had expressed continuing interest in this showdown taking place—although not at Louisville. A race held September 25 at Cincinnati would be acceptable—if Alexander agreed to race his colt again the following summer at Saratoga. Wilkes had not forfeited an opportunity during this time to stir the pot of controversy a little more. He suggested that Alexander’s disdain of Saratoga revealed an ugly “portion of a plan to contribute nothing to racing in the North.” Here was a barb that revealed the tension between the old and the new centers of power in the racing world as well as one playing on four years of ill feeling that had existed between North and South with Kentucky caught in the middle. Alexander’s response, sent through his intermediary, consisted of six words: “The propositions do not suit Alexander.”29

Shortly afterward, Alexander relented and agreed to the terms of Cincinnati during 1865 and Saratoga during 1866. Too much ill feeling had arisen by this time, however, and Wilkes had not helped with his ranting to keep feelings on either side on an even tone. At one point Wilkes had written: “It is plain, therefore, that Mr. Alexander will have the proposed match his own way, or he will not have it at all.” The controversy matched the old gentry against new money, and readers undoubtedly loved reading every word about this confrontation. But the central question remained: Why had Kentucky’s owners assumed that Asteroid would need to race in the Northeast to settle the championship? One of Alexander’s supporters in the Bluegrass asked: “Is the case to be made different to the East of the Alleghenies?”30

Perhaps Alexander had not wished to see nouveau money in the Northeast push him to the wall with demands for a showdown between Kentucky and Asteroid. Or perhaps, as his acquaintance explained in a lengthy letter to the sympathetic Turf, Field and Farm, he had been too preoccupied with reestablishing his own stable after the war to plan for a trip east with Asteroid. “It was Mr. Alexander’s intention to have taken his horses North this summer had they done well,” according to the letter writer, who signed his name Fair Play, “but owing to the outrages committed on him by guerillas, entailing a loss over sixty thousand dollars in stock, some that cannot be replaced, among them Nebula, the dam of Asteroid, and his own life and safety jeopardized, he had to remove all his stock from Kentucky, upwards of three hundred head, including stallions, broodmares, colts, and trotting stock…. When he got through his western engagements he had but one horse—Asteroid—fit to travel with.” The writer went on to explain that, Alexander having but one horse trainer to put in charge of all his horses, his interests would have suffered if he had sent that trainer to Saratoga with Asteroid. For those in Kentucky who had endured guerrilla raids and the theft of their horses, this explanation would have seemed quite reasonable. Apparently, it did not seem so to the new titans of the Northeastern turf.31

Sectional interests and rivalries had entered this controversy at every turn, and Bluegrass horsemen expressed their disgust with the Northeast by threatening to withdraw their subscriptions from the New York–sbased Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times. The editor responded, calling the Bluegrass folk “narrow-minded” persons who viewed this and other racing matters in terms that were “sectional between the West and East.” Fine, Wilkes said in his own defense. If readers wished to withdraw their subscriptions, so be it; the Spirit would survive on the patronage of “true patrons of this paper.” However, this did not relieve Alexander of his responsibility to race Asteroid, according to Wilkes. Because Alexander possessed the finest breeding stallion in the United States—the sire named Lexington—people in the North believed that he was able to manipulate bloodstock prices nationwide with this one horse. Therefore, he owed the sport an opportunity to see Asteroid race against Kentucky. “The side we represent,” the editor intoned in his chauvinistic vein, “desires to promote the interests of the turf, by having the colt Asteroid come on and run; the other side, which seems to be composed mainly of those who are the natural followers of close rich men, have sprung forward to defend Mr. Alexander’s personal right to keep his colt to himself, though the general interest should suffer.” East versus West, folks were lining up in opposition. It seemed so long ago, not just four months, that the lineup had been North versus South.32

The summer’s outcome disappointed all. The Saratoga Cup went off as scheduled but without Asteroid. With the talented Irishman Gilbert Patrick, better known by his nickname, Gilpatrick, riding Kentucky, that colt easily defeated the only other two horses to start: Captain Moore, who finished second, and a horse from the Bluegrass named Rhinodyne. The renowned Abe Hawkins, the dean of black jockeys and a former slave whose riding fame would span the antebellum and postwar eras, rode Rhinodyne. The horses raced in the new style, going a lengthy two and a quarter miles but not returning for multiple heats.

A breezy, sunny day greeted the crowd of spectators for the Saratoga Cup, a good number of them women wearing the latest fashions, a touch that added a pleasant aspect to the spectacle. “No clouds gathered to darken the blue of the sky,” reads a report of the race. The same could not be said of Alexander’s standing with the Northeastern racing community, which had longed to see Asteroid in this race. Alexander’s aloofness had cost him respect in the Northeast. Clouds of a similar nature were beginning to darken the relevance of Bluegrass horse country and its place at the center of power in Thoroughbred racing. Folks in the Northeast were no longer looking to the Bluegrass for leadership in this sport. They were making over the sport to suit themselves whether or not Alexander chose to participate.33

So much had changed since the late 1850s, when New Yorkers had looked to Bluegrass Kentuckians as Thoroughbred racing’s leaders, seeking their help in resurrecting the sport in the Northeast. That situation, too, had represented quite a change from previous decades, when New York racing had been quite in vogue. But Thoroughbred racing had operated cyclically for so long in New York, depending on whether antiracing interests held power, that no one there could breed and raise Thoroughbreds with any assurance that there would be tracks where these horses could race.

From 1821 to the later 1830s, New York racing had existed as the epicenter of Thoroughbred racing and had hosted widely anticipated match races between Northern and Southern horses like Eclipse and Sir Henry. These races, some fifty of them, had taken on national import in the 1820s and especially in the 1830s following the Missouri Compromise. Adelman has suggested that these races assumed symbolic connotations for their Northern and Southern audiences, given the hardening feelings between North and South. Despite the increasing sectional animosities and the difficulty of travel, Southerners had brought their best horses north for these showdowns, which took place at the Union Course on Long Island. New York, with its large population base, provided the largest audiences and the greatest number of wagering opportunities, with the betting playing a significant role in these races. Some sixty thousand persons might have witnessed the Eclipse–Sir Henry match in 1823, although these estimates taken from contemporary press accounts may have been exaggerated. Eclipse defeated Sir Henry. The North and New York won that round.34

The economic collapse of 1837 hit the gentry class of horse breeders hard, particularly in New York, where the financial base of elites was grounded in industry and commerce, both sectors that were suffering in the depression. The final North-South race of any consequence was the Fashion-Peytona match in 1843; quality racing was in a free fall and virtually died out in New York by middecade. New York racing had hit the bottom again in another of those seemingly endless cycles that witnessed the sport rise and fall in this state through the decades.

The sport had been banned entirely in New York in 1802 with an antiracing law brought on by social reformers who disliked the gambling aspect; it had returned only two years prior to the Eclipse–Sir Henry match of 1823 after legislators changed the 1802 law. Eclipse’s owner brought the horse out of retirement on the legislative change—he had been at stud and would be nine years old by the time of his race with Sir Henry, the Southern horse he defeated.

Two decades later, following the Fashion-Peytona match in 1843, sectional feelings between North and South had become so hardened that no further matches of consequence in New York occurred, although match races of similar import were taking place in New Orleans among horses representing various Southern states. Meanwhile, the Union Course in New York suffered from the twin blows of depressed economic times and mismanagement. Trotting horses and racing mules soon replaced the Thoroughbreds. Both were less expensive to maintain than the sleek racehorses that had formerly thrilled huge audiences.35

Economics aside, John Dizikes has suggested that cycles of expansion and contraction in New York horse racing paralleled periods of unrestrained gambling and fraud followed by social revulsion and alarm, the latter resulting in periods of prohibition of gambling. In hindsight, these cyclic swings throughout the nineteenth century foretold the future for racing in New York when Progressive reformers managed to shut down racing once more in the state, from 1910 to 1912: a situation that greatly affected the Bluegrass. With each waning cycle of the sport on the racecourse came a parallel decline in the breeding of Thoroughbreds in New York, to the point at which only a single Thoroughbred stallion stood at stud on Long Island prior to the Civil War. At the same time that New Yorkers sought the aid of Bluegrass breeders in the late 1850s to revive their sport, the Spirit of the Times equated the paucity of breeding in New York to the poor quality and insufficient number of horses racing on the track, a situation obvious to everyone “because we had no horses in this section of the Union fit to contend with even second- or third-rate Virginia horses.”36

The Spirit described the situation as deplorable, noting: “Our Race course has fallen into disuse from want of Northern horses to compete successfully for the prizes, and we have witnessed numerous attempts to revive racing before the public in our vicinity were prepared for it, all of which have failed.” The solution seemed to be to invite the racing men of Kentucky—“the Dukes, Vileys, Alexanders, Richards, Hamptons, Bradleys, Hunters, and Clays”—to combine with wealthy Northern sportsmen in rebuilding the sport in New York. As this sporting periodical made its case, it reminded Bluegrass horsemen than they would be able to expand the market for their horses this way since, of 1,200 Thoroughbreds born annually in the United States, “Kentucky alone contributed 450 thoroughbred foals this year.” The New Yorkers realized that they could not interest Kentuckians simply with an altruistic motive; they would have to appeal to their business needs.37

No record can be found of what the Dukes, the Vileys, Alexander, or John Clay thought of this plea for help. But some of the betterknown Kentucky horsemen had accompanied their racing stables to Philadelphia in 1862, the second year of the Civil War, to compete on a circuit that temporarily sprang up between that city, New York, and Boston. Zeb Ward and Captain T. Moore were the first to arrive; expected within a short time were the stables of Dr. Weldon, John Clay, and R. A. Alexander. The organizers acknowledged the superiority of Kentucky horses and advised that, for the opening race at Philadelphia, “horses that have won in Kentucky, at the Spring meeting, will be excluded from starting for this purse.” Another race at Philadelphia was open only to white riders mounted on saddle horses. This meant that black (slave) jockeys brought up from Kentucky were to be excluded from this race with its prize of a gold watch inlaid with diamonds. The “gentlemen” entering their saddle horses for this race were required to pledge that, if they won the watch, they intended to make it a present to a “lady,” a subtle suggestion that the presence of women at the racecourse was an integral part of the spectacle. New York planned to offer a similar gold watch, made by Tiffany, with the winner again sworn to present the watch to some lucky “lady.” Ten stables of racehorses had assembled for these short meets, with the New York Times concluding that this gave “an assurance of the best racing ever seen in the North.” The Kentuckians undoubtedly arrived pleased to find a place to race their horses, for, other than the track at Lexington, racing in the South lacked continuity during the war years.38

By 1859, New York remained without racing, although some twenty-five men were raising Thoroughbreds in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and New Hampshire. Perhaps they had planned to race these horses in the South. Or perhaps they bred them merely for the pleasure of owning them, albeit without any decent place in the Northeast to race them. These men included William Astor (destined with his brother, John Jacob Astor, to inherit an estate of some $100 million), John Hunter (an eventual partner with Travers and Osgood in the horse Kentucky), Francis Morris (whose family’s racing silks were the oldest in use in the United States), and William Bathgate (the owner of the Fordham, New York, estate that later would become Jerome Park). Belmont, Jerome, and Travers were not yet among this group but soon would be. When these three took up racing as a sport, the progress of the Northeastern turf would charge forward on a fast track.39

Despite the interest of these wealthy men, racing still had not returned to the mainstream of New York culture. In 1859, the editor of the Spirit lamented how Thoroughbred racing had slipped into such oblivion that even the rich were unfamiliar with the sport. “Very few of these gentlemen are acquainted with the details of racing, and the public have in a great measure lost their former love of it from the scarcity of close contests and repeated disappointments,” he opined. He spoke of the need of education about the sport among both breeders, “in order to resuscitate in old patrons of the Turf their almost dormant love of racing,” and the public, especially “the young,” who “must be taught to appreciate it.” Far from anticipating the sectional divisions that would come with the Civil War—and the disunity that followed—the Spirit of the Times suggested that stock certificates in a racecourse near New York be sold not only in the Northeast but also in the West and the South. The Spirit estimated that the New Yorkers would need some $60,000-$70,000 to build such a racecourse.40

Nothing came of this proposal. Whether Alexander and other Bluegrass horsemen received a direct request for help is not known. But the fact that Northerners had seen them as leaders in the sport and in the practice of breeding Thoroughbreds in 1859 was telling, given the change of perspective that New Yorkers had adopted by the end of the war. In the minds of the new breed of racehorse owners in the Northeast in 1865, the relevance of horse country had faded. Northern men felt secure in the notion that they had released the South’s stranglehold on the sport and shifted the center of Thoroughbred racing back to New York.

The war had brought changes North and South, among these a 43 percent decline in Southern wealth. Along with the closing of numerous Southern racecourses, this did not portend a strong market for racehorses in that section of the country. In contrast, new, Northern fortunes had emerged during wartime from industry and Wall Street speculation. Families flush with new money placed their wealth and status on display in a variety of ostentatious ways, not the least of which was the ownership of fabulous racing stables.41

Social leaders like Belmont were raising the profile of the sport in the Northeast, lending horse racing a cachet of legitimacy it had not known there in decades. Men of Belmont’s group also brought to the sport in the Northeast a set of practices that revealed how they planned to change the appearances of Thoroughbred racing. For example, instead of riding on horseback or traveling in buggies to the races, as Kentuckians generally had, these men arrived in magnificent heavy coaches pulled by teams of four well-matched horses. In this practice, they mimicked traditions borrowed from England.

August Belmont played perhaps the most significant role in the revival of Thoroughbred racing in New York after the Civil War. He founded the Nursery Stud on Long Island, eventually moving his breeding operation to the Bluegrass in 1885. His son, August Belmont II, was the breeder of Man o’ War, foaled at Nursery Stud in Lexington, and arguably the greatest of American Thoroughbreds. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

Belmont and Jerome both were skilled coaching men who drove their own four-in-hands, a team of four look-alike horses trained to pull these heavy, English-looking rigs. Liveried servants and guests accompanied their hosts, the guests seated inside and atop the coaches, with all appearing to enjoy a jolly good time. On reaching the racecourse, the servants pulled from each coach’s boot a well-packed, fancy picnic, in keeping with the English coaching tradition. The Coaching Club American Oaks is a Thoroughbred race in New York named in honor of the organization that Belmont and his peers supported. Quite overnight, it seemed, the rich were adding their own socially conscious, English touches to this increasingly fashionable sport.

The ownership of racehorses appeared to be the perfect choice for wealthy men and their expansive egos. Nothing bespoke the wonders of a bottomless fortune quite like a stable of sleek, fast horses that were expensive to buy, beautiful to look at, and costly to maintain. Racehorses always have served as signifiers of wealth and status. The timing also was perfect for the sport to reemerge in the Northeast: this was precisely the time when increasing numbers of men successful in the worlds of business and industry were looking for ways to spend their fortunes. These highly competitive businessmen were discovering in racing a new arena where they could transfer their rivalries from the business and social worlds. Racing was proving to be a great game of one-upmanship. Expansive egos drove these men to racing and would bring them to spend vast amounts of money in this highly expensive sport even when they had little or no hope of making their racehorses pay for themselves. The purses were not large enough to pay for the upkeep of their stables.

Typically, the majority of these powerful new men in Thoroughbred racing lived in the city of New York. This demographic marked a clear break from the antebellum status quo in the Bluegrass, where the major landowners and an elite class of moderately wealthy gentlemen farmers had ruled the sport. The ownership of the racehorse Kentucky revealed just how clearly the sport that was reviving itself in the Northeast had shifted away from previous ownership patterns: Travers, Hunter, and Osgood all were urbanites and residents of New York. Their social and business interests were centered almost entirely on the city, except when they summered at the village of Saratoga Springs, where Travers served as president of the racecourse. They had not even traveled to the Bluegrass to purchase Kentucky. John Clay, the breeder, had brought the colt to the Northeast to sell.

Travers, a lawyer who had made a fortune on Wall Street, was the most recent of the three partners to take up Thoroughbred racing. He was a dapper sort who fully appreciated life’s pleasures, taking up membership in twenty-seven social clubs. Friends and acquaintances overlooked an unfortunate impediment in his speech: he had a slight stutter. They did, however, appreciate his quick sense of humor. He loved to poke fun at everyone, even his own kind—the men of Wall Street. Once, when he and a companion passed by Manhattan’s Union Club, the companion asked him whether the men sitting in chairs by the windows were habitués of the private club. “No,” Travers replied, “some are s-s-sons of habitués.”42

On acquiring the racehorse Kentucky, Travers experienced enormous beginner’s luck. For the $6,000 it cost to purchase the horse, Travers wound up striking gold. Many more owners of racehorses have spent a lifetime throwing good money after bad horses while never acquiring a horse of this quality. Yet, just as he had on Wall Street, Travers once again exhibited his Midas touch. He could afford to spend whatever he wished to acquire any horse he wanted, but in this case he did not have to spend a fortune. He just spent more than most men could afford.

Some New Yorkers had amassed fabulous fortunes: the retailer Alexander T. Stewart had made more than $1 million during the year 1863. Seventy-nine residents of New York earned more than $100,000 that same year. Two years previously, when the Civil War had begun, the estimated number of millionaires residing in New York was 115. The rich were growing richer, with a growing number of them turning to horse racing for sport.43

Kentucky’s owners, like other New Yorkers entering Thoroughbred racing, found themselves in good company with Belmont in the sport. Belmont was a smoothly polished urbane sort who exemplified elite society, showing the way to others in his class with the fascination he had developed for fast horses. Paradoxically, he was a self-made man. He began his working years sweeping floors in Germany for the moneylending Rothschilds financial empire and had advanced to a position as its American representative. He also owned his own bank. As a society leader, he had no peer. New Yorkers regarded him as the symbolic ruler of Fifth Avenue, and rightly so. He had shown so many of them how to live and enjoy the good life.

Thoroughbred racing at Jerome Park, which opened in 1866, drew New York society leaders as well as Bluegrass horsemen, who brought their stables to the Northeast. Jerome Park, with August Belmont serving as its first president, almost overnight became the leading racecourse in the United States. This new racecourse assumed the preeminent position in the sport, which Southern racecourses, in particular the Metairie track in New Orleans, had held before the Civil War. (Courtesy of the New York Public Library.)

Leonard Jerome, a lawyer like Travers and also a financial wizard on Wall Street, was soon to become the founder of several racetracks in the Northeast. To his dismay, he had missed the inaugural meet of Saratoga racing in 1863 because he was otherwise occupied, manning a Gatling gun from a window of the building housing the New York Times. He was a major stockholder in the newspaper and was intent on protecting his investment. To that end, he had aimed his gun on the masses, many of them Irish, who were rampaging through the streets in riots that broke out in 1863 over the army draft. Jerome made up for lost time, however, and was in attendance at Saratoga in 1864 and 1865.

In 1865, Jerome changed American racing forever. That year he founded the American Jockey Club, and, by 1866, the club opened the most modern, lavish, and elite racetrack yet seen in North America. The track was situated northeast of the city in Westchester County on the old Bathgate estate. The American Jockey Club members, quite an exclusive set, named their racecourse Jerome Park. Belmont served as the initial president. Jerome, like the others, grew only wealthier. He invested in railway companies and enjoyed yachting with William K. Vanderbilt. He also partnered with Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt in railroad deals. Much later, following his death in 1891, he gained additional status as the grandfather of Sir Winston Churchill.44

Jerome’s friend Cornelius Vanderbilt did not participate in Thoroughbred racing, favoring instead the trotting matches that also were popular at this time. This had not stopped the commodore from throwing his considerable support behind Travers and others in founding the Saratoga Racing Association. He patronized racing and the other gambling activities of the Saratoga summerfest, as did multimillionaires like William B. Astor, said to be the richest man in the world with his fortune of $61 million. With Astor, the commodore, and Jerome joining Travers, Hunter, and Osgood at Saratoga Springs during summer, the season must have been awe inspiring, one multimillionaire after another strolling down the village avenues.45

Alexander, the owner of Asteroid, also owned a sizable fortune. Contemporary accounts identified him as the second-wealthiest man in Kentucky, behind his close friend and fellow horse breeder Alexander Keene Richards of Georgetown in Scott County, Kentucky. But that was before the war; Alexander might have surpassed him. The friendship between these two men was such that they oversaw the care of each other’s slaves and horses when necessity arose. Unlike Kentucky’s owners, Alexander had passed nearly all his life in rural regions. Yet he was anything but a country rube.

He had graduated from Trinity College at Cambridge University in England after spending much of his youth on his uncle’s Airdrie estate in Scotland. In fact, Alexander was quite the man of the world. He had inherited his uncle’s title and wealth, which included a highly productive mining and refining operation in Scotland called the Airdrie Iron Works. Alexander returned to the United States to live in 1849, bringing with him expansive ideas gleaned from his travels in Europe: visions of the way an ideal livestock breeding operation should be designed, grounded in the notion that ideas promulgated in England or on the European continent were the goals that Americans should strive for. He bought up portions of the family’s Woodburn Farm that had been divided among his siblings on their father’s death. He set about planning and designing the layout of a farm that his contemporaries began to view not only as mammoth but also as a model that they would be wise to copy. “The breeding establishment at Woodburn is modeled on the most approved English plan,” the Kentucky Gazette noted in 1866 with an approving nod. The stables for horses and cattle were vast and made of cut stone; the dairy houses, also built of cut stone, were managed by Scottish dairymaids.46

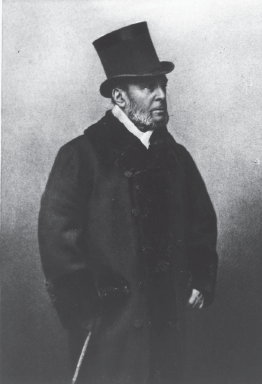

Robert Aitcheson Alexander, the owner of Woodburn Farm in Woodford County, Kentucky, was a sportsman, an agriculturist, and a visionary who stood the famed sire Lexington at stud. He also was recognized for the premier trotting horses he bred and stood at stud. His contributions to the progress of the sport were immeasurable. (Courtesy of Woodburn Farm.)

New Yorkers sometimes mistook Alexander for an Englishman, an understandable error since Kentuckians frequently called him Lord Alexander; it is even possible that he spoke with a slight British accent after spending his youth in Scotland and England. New Yorkers clearly saw him as set apart from the average person traveling up from Kentucky, for Kentuckians still bore somewhat of a frontier appearance in the minds of Easterners. Illustrative of this was one story told from the racecourse after reporters observed Alexander kneeling so that women standing behind him could have a better view of the track. One reporter remarked how this expression of good manners surely must be English. Another corrected him, writing: “[Alexander] was born in Woodford County, Kentucky, and lives on the home place of his father.” Yet he did seem more English and less like a Kentuckian, the latter a type that Harper’s magazine had characterized as a knife-wielding frontiersman.47

In manners, wealth, and social customs, Alexander assuredly came from the upper class. His father, Robert Alexander, was a native of Scotland who had received his education in France and become acquainted with Benjamin Franklin, at that time serving as the U.S. ambassador to France. The senior Alexander followed Franklin to the United States, later moved to Kentucky, acquired the property he named Woodburn, and became president of the Bank of Kentucky in Frankfort. He built a log cabin on Woodburn but never lived on the farm. The son who took up residency at Woodburn was Lord Robert Aitcheson Alexander, following his college years spent in the British Isles. He moved into the log house his father had built, expanding it to a sizable residence while maintaining the log porch exterior at one end.48

While some thought him English in his manners, Alexander also evoked popular notions of the archetypal plantation owner. His vast Woodburn Farm was sufficiently large, between three and four thousand acres, to pose the picture of a small plantation to those Northern writers who visited before and after the Civil War. Taking full advantage of the slave labor available in Kentucky, the younger Alexander developed his vast livestock cattle and horse-breeding operation into a model farming enterprise renowned throughout the United States prior to the Civil War. He owned several excellent trotting and Thoroughbred stallions, including Lexington, sire of that renowned triumvirate of excellent racehorses all born in 1861: Asteroid, Kentucky, and Norfolk. Alexander had sold Norfolk for a record $15,001 (exceeding by $1 the record $15,000 he had paid for the sire, Lexington) to a mining and transportation mogul in California named Theodore Winters. But he was to state many times over that he believed Asteroid to be the best of the three.49

Alexander was justifiably proud of Asteroid. In this horse more than any other, he saw his theories and agricultural practices approach as close as possible to perfection. He had set out to breed livestock in a highly organized manner according to those proved crosses of bloodlines that were known to result in success. He practiced this method during an era when some horse owners persisted in the old ways, breeding their mares to whatever stallions were closest to their farms, simply because this was more practical. Mares had to be walked or ridden or shipped to the breeding stallions via unreliable railroad transportation; this was difficult and, in many cases, impossible if one lived in a truly remote area.

Alexander had divided Woodburn Farm into well-organized sections so that the trotting horses were relegated to one area with their own exercise track close by and the Thoroughbreds had stabling quarters in another section with their track close to their stables. Everything Alexander did with his livestock he carried out with great planning and organization. He maintained journals and breeding records. He expressed particular interest in bringing order to the disarrayed state of American pedigrees in Thoroughbreds and trotting horses.

To Alexander’s thinking, American horse pedigrees existed in such a state of disorganization that no one could know for certain which bloodlines would cross most profitably. Moreover, no one could be certain whether the stated pedigree of any mare or stallion was correct—or whether it was fabricated, something Kentuckians were frequently accused of. Alexander had vowed to bring order to the confusing state of American Thoroughbred pedigrees. He asked anyone sending a mare to the stallions at Woodburn to also send a written record of her family history, believing that all would tell the truth. He relied on his superior knowledge of pedigrees to feel certain when other breeders were truthful. “Those who knew him know that no man in Kentucky in his time was so well posted in pedigrees, and none was more careful and thorough in his investigations,” Busbey wrote. “He made no mistakes. He was the one man that sharpers avoided.”50

Alexander had assembled at Woodburn an excellent band of broodmares and three valuable stallions: Lexington (standing for a breeding fee of $200), Scythian (with a $75 breeding fee), and Australian (with a $50 fee). He kept careful records of the Woodburn broodmares and their progeny in a printed guide called a catalog that he published privately each year. He was believed to be the first of American breeders of Thoroughbreds to produce such a catalog; he certainly was the first to print a catalog of horses and livestock he offered for sale in the public auctions he held at his farm. The Woodburn catalog for 1864, for example, noted that the broodmare Nebula was the dam of Asteroid but had not produced a foal in 1864.51

The original owner of Nebula, Jack Pendleton Chinn, had sent the mare to Woodburn for safekeeping during the war; Alexander came into ownership of the mare during that time. Alexander’s friend Richards, of Georgetown, had done the same with the stallion called Australian, selling him to Alexander soon after the start of the war. The intent of these horse owners to put their horses in safekeeping on Alexander’s estate must have seemed ironic as the war progressed. Alexander’s neighborhood grew quite dangerous, with outlaws stealing Asteroid and other valuable trotters and Thoroughbreds. All Kentucky was a dangerous place during these times, and Woodburn Farm was no exception, despite what all had wanted to believe. Alexander had thought he would be safe from marauders because, as a British citizen, he flew the British flag. But he was not safe, as events would show.52

Americans of this time had some basic knowledge of Woodburn Farm, partly because travel writers had begun visiting the estate prior to the Civil War. Visitors had written glowingly, describing a vast property situated at the heart of a region “undeniably [the] ‘game bed’ of the United States, in blooded horses, stock, and chivalrous sons and daughters … [where] horses were brought out, and led around for our inspection, and negro boys attended us everywhere.”53

Visiting writers unfailing painted the squire of Woodburn as a kind and charming gentleman farmer of cultivated manners. They told how he resided without a wife in a home that his slaves made comfortable for him. They described how he had enlarged his home over the years from its log-cabin beginnings to a house of ample proportions that retained the log-cabin facade on one wing. Alexander had filled the house with elegant furnishings, which customarily drew comment from his visitors. Visitors also reported on the pleasing hospitality that he dispensed with ease at his laden table. If nothing else, this picture of Woodburn Farm was helping reinforce emerging images of Kentucky horse country as a place stocked with fast horses, of “negroes” attending the horses and guests, and of a patrician gentry class that dispensed hospitality in the fashion of knightly cavaliers more often associated with the Deep “Cotton” South.54

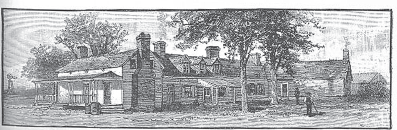

Robert Aitcheson Alexander lived in this home, which had retained its log facade along one side, evoking imagery of the late eighteenth century and the early nineteenth, when Bluegrass Kentucky stood at the edge of the Western frontier. (Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, October 1883, 729.)

Whether this vision of Kentucky horse country was to remain relevant to the new world of Thoroughbred racing was another question entirely. The new capitalists getting into the sport were bringing their own culture to the game; they brought an urbane style that disconnected their practices from the quasi-plantation traditions of Kentucky horse country. The English-type coaches in which they traveled to the races represented one expression of this break from Bluegrass tradition; the private stud farms they were building close to the city of New York represented still another. These new farms featured the latest improvements in the training and housing of horses and, thus, did not entirely resemble the older, established farms in Bluegrass horse country. In these and other ways, it was clear these new men were bringing their own ideas to the sport. The cultural practices and iconography that had linked Thoroughbred racing with rural, Deep South plantation imagery and traditions before the war now teetered between the new, urban style and antebellum obsolescence.

Alexander might not have felt a connection to these new men from the Northeast like Travers and his group. He appeared uninformed about their identities, perhaps even disdainful of the position they already had assumed in the sport. On at least one occasion, he referred to Kentucky’s owners not by name but as “some New Yorkers,” as though dismissing their identities and relevance to the sport as he knew it in Kentucky. A slip like this might have seemed unconscionable to racing enthusiasts in the Northeast, however, where men like Travers considered themselves the essence of New York society and sport. But Alexander continued to see the Bluegrass as central to the sport. He had the best horses. His horses had the proven bloodlines. He held the power in Bluegrass Kentucky, where other horse breeders looked to him for leadership. If “some New Yorkers” wanted to play at his level, perhaps it was understandable for him to assume that they would have to play his way.55

This might have been one reason why Alexander ignored, at first, the pleas of Travers and his group to bring Kentucky and Asteroid together in the Saratoga Cup. Besides trying to reestablish his racing stable after the war, he was meeting during the Cincinnati race meet in June with other leaders of the Western sport. They were attempting to bring order to horse racing in Kentucky, Ohio, and Missouri now that the war was over. Unfortunately, the intensity of the desire for the race between Asteroid and Kentucky was building in the Northeast just as Alexander was deeply engaged in his organizational efforts.

Alexander met with these men to establish an orderly racing circuit in the Western region. With Alexander representing the Woodlawn Course in Louisville, they worked out a plan so that the various meets in these states would not overlap or run simultaneously. Their concern was to put racing back on a sound and orderly basis without delay. With so much to consider in their own region, they might not have been thinking at that particular moment about the rise of the sport in New York. It must have seemed an odd paradox when a representative of the Saratoga Race Course arrived at the Cincinnati track to begin taking bets on the showdown between Kentucky and Asteroid, to take place in New York, where the new men of the turf seemed disinterested in the Western sport.

While Alexander attended these important organizational meetings at the Cincinnati race meet, his horses also fared exceptionally well on the racecourse there. This was remarkable, considering that he was only beginning to reorganize his stable after the two raids on Woodburn Farm: one in the autumn of 1864, when thieves took Asteroid, and then the most recent raid, in February 1865. The story of Asteroid’s theft was well known to racing enthusiasts across the United States, as general newspapers and Wilkes’ Spirit had reported on the incident.