Some 460 million years before horses like Kentucky and Asteroid appeared on American racetracks, central Kentucky and Middle Tennessee formed their destiny as horse country. This occurred during the Ordovician Period, a time of major plate collision of the earth’s crust, along with volcanism on what would become North America. Continents moved, mountains formed, and vast seas opened into a shallow marine shelf that was to form the central portions of the east-central United States. Surging seas swept over this shallow shelf, bringing with them the millions of invertebrates that left behind a precious natural gift, their fossilized shells, which gave rise through the millennia to a particular form of limestone rock, the building block that horsemen have long believed is critical to raising a strong-boned racehorse.

The structure of this rock includes the calcium carbonate that composes most limestones. However, and more importantly to horse breeders, the composition of this particular limestone includes a heavy concentration of phosphate, an occurrence that Professor Frank Ettensohn, a geologist at the University of Kentucky, has stated is relatively uncommon and occurs in few other places outside the Bluegrass. Ettensohn has theorized that the phosphate plays a greater role in growing a strong horse than does calcium carbonate by itself. During the early nineteenth century, Bluegrass horsemen appeared unaware of the contribution the phosphate made to the rock; they believed that the limestone itself was responsible for the exquisite flavor found in beef and sheep raised on this land. They believed that the limestone made the same contribution to those strong-boned horses raised in the Bluegrass, horses they described as “hickory-boned.” These nineteenth-century Americans might not have realized fully the composition of the limestone, yet they still seemed aware that the soil drew its strength from it. In 1865, the Louisville Journal attributed the quality of Bluegrass livestock to “the stratum of blue limestone which underlies the whole country at the distance of from ten to twelve feet from the surface, and perhaps has some effect on the grass.”1

The soil, the limestone, and the Kentucky bluegrass that grew on this gently rolling land continued to fascinate observers who wrote about this verdant section of the United States. In 1876, the Harvard professor Nathan Southgate Shaler, a geologist and paleontologist, wrote that Bluegrass land was “surpassed by no other soils in any country for fertility and endurance.” Around the same time, an article in the London Daily Telegraph cited the mineral benefits that horses in the Bluegrass received from the soil. In 1980, the University of Kentucky professor Karl B. Raitz succinctly described the Bluegrass region as “a broad limestone plain which has been etched on a structural arch of Ordovician limestones and shales.” Noting the phosphatic content in combination with calcium, he wrote: “The gently rolling terrain is underlain by phosphatic Lexington and Cynthiana limestones which decompose into exceptionally fertile silt loam soils.2

Early in the nineteenth century, central Kentucky and Middle Tennessee both became known as “the Bluegrass,” the name taken from the Kentucky bluegrass that flourished in their fields. No one has ever produced definitive answers on whether the legume that made the reputation for these regions actually possesses a blue hue and whether it is native to these states or originated someplace else, perhaps in Europe. “Whether the grass of the Blue Grass region be indigenous, or transplanted here at an early day by artificial means we have not room to discuss,” observed the Lexington Transcript in 1889, adding: “Anyhow, it lies at the foundation of our immense stock business…. It makes fine whisky, cattle, trotters and runners, and gives strength to our men and symmetry and beauty to our women.” Thus, even though no one knew the origin of the grass, folktales abound about Poa pratensis, more commonly known as Kentucky bluegrass.3

Some say that, if you observe the grass in this region just at dawn, when the dew lies heavily on it, you will see a hint of blue. The folklorist R. Gerald Alvey has related still another way in which people have attempted to explain the presence of this supposedly blue-tinted grass. He told how people observed a bluish vein running through the limestone and believed that the constantly decomposing blue limestone was responsible for the blue grass. Most importantly, people believed even decades before the Civil War that livestock in this region absorbed through the grass the important minerals that the limestone rock gave up into the rich soil. Equally as important in their eyes were the natural springs that spilled water infused with the same minerals into farm ponds and streams where livestock drank.4

Bluegrass breeders learned early on how to exploit this natural agricultural gift of the soil and turn it into a rich resource, combining the nutrition that it provided to grazing animals with their own ever-widening knowledge of equine pedigrees. Long before the mid-nineteenth century, Americans recognized that the strongest, fastest racehorses came from the Bluegrass region. This had occurred not by accident, but thanks to the gift of the land and the breeders’ continuous attempts to upgrade the quality of their stock.

After the Civil War, the unexpected rise in the number of fabulous horse farms under construction in the Northeast represented a new direction for the sport, one that challenged popular notions about the unique value of Bluegrass soil and grasslands. In fact, the owners of these new estates appeared to have ignored altogether the benefits that Bluegrass horse country offered, with its mineral-rich land and the superior equine bloodlines. The trend was becoming obvious to all: Belmont, the society leader and banker; Travers, the financier and president of the Saratoga Race Course; Milton Sanford, the textiles mogul; and the Lorillard brothers, Pierre and George, heirs of the vast tobacco fortune, were building their own horse farms to complement the growing number of racetracks in the Northeast. Just as men like these already had shifted the center of racing away from the South and the border states, now they appeared to be starting a new trend by developing their own breeding farms in New Jersey and New York. Bluegrass breeders undoubtedly would have viewed this as problematic to their interests, for it hinted at the possibility of horse country becoming obsolete or at least diminished in relevance. Either way, the problem threatened to hit directly at the pocketbooks of Kentuckians. Just as breeders were regrouping after the war, trying to replenish their stock or rebuild their farms so that they could begin earning an income again, extremely wealthy men in other states were seizing those financial opportunities out from under their grasp.

This increasingly popular trend reached a critical point when the racing career of that highly accomplished racehorse Kentucky came to a close in 1866. As we have seen, Travers and his group sold the horse for a record $40,000 to Leonard Jerome on the horse’s retirement to the stud. Instead of returning to the state of his birth, however, Kentucky stayed in New York, moving to new quarters close to Jerome Park to begin his breeding career, stinted to mares whose owners had no intention of sending them to breed to stallions in the Bluegrass. Two years later, in 1868, Belmont purchased Kentucky from Jerome for the purpose of installing the horse at his Nursery Stud on Long Island. In fact, Kentucky never returned to stand at stud in the state for which John Clay had named him. No one in the Bluegrass took this lightly.

Breeders in Tennessee also made an effort to get back in the business of breeding and raising racehorses; this, too, would provide more competition for Kentuckians. In Tennessee’s historic horse country near Nashville, where Andrew Jackson had founded a racecourse before becoming president of the United States in 1829, breeders took the lead in restarting their programs from the premier plantation of that state, Belle Meade. This particular horse-breeding operation had been recognized for its quality and the quality of horses it produced since long before the war. Within two years after the war, it took a significant step toward regaining some of its renown by holding its first yearling auction. Neighbors of Belle Meade, many of them breeders of Thoroughbreds, depended on this plantation for guidance and organization at a time when they were attempting to find a niche in the new marketplace.5

“With the probable exception of Woodburn Farm” in Kentucky, writes Ridley W. Wills II, this queen of Tennessee plantations, Belle Meade, “was considered America’s greatest breeding establishment.” During the 1870s and 1880s, the estate’s renewed success would see it achieve nationwide recognition once again, largely through annual yearling sales held at the plantation and also, for a time, in New York. The farm also gained renown for the valuable stallions it stood at stud, among them Bonnie Scotland, Enquirer, Vandal, John Morgan, Iroquois, and Luke Blackburn. General William Giles Harding, the master of the plantation for forty-four years, was recognized after his death at age seventy-eight in 1886 as a man who “had done as much for the breeding interests of Tennessee, and perhaps for all America, as any man in the nineteenth century,” according to Wills. As Wills also points out, Harding’s generalship of Belle Meade attained such renewed standing for the plantation after the war that it “was one of the few places where the Old South was brought over into the new.”6

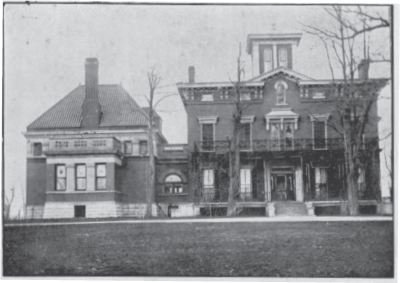

The great mansion, paddocks, and pastures stocked with fine horses led Northern horsemen who visited during yearling auctions to believe that this was what the Old South had looked like during the antebellum period. Six columns, each twenty-two feet in height, composed the portico of the residence. The columns, each cut in two sections of limestone taken from quarries on the plantation, represented the craftsmanship of Belle Meade slaves. The appearance of this house undoubtedly figured into notions that Americans constructed decades later, after the demise of Belle Meade, when Kentucky’s Bluegrass horse country assumed the mantle as representative of the Old South. The portico of Belle Meade was well recognized throughout the United States, for writers had been describing the columns since before the Civil War. “It is true that the massive towering stone pillars that are seen in front, impress one more with the idea of extravagance than utility,” wrote a newspaper correspondent for the Nashville Union and American in 1854, “yet they so agree in architectural beauty with the whole, that economy would even not seem to require their removal.”7

Despite the devastation that its herds and physical structures suffered, Belle Meade was able to recover fairly quickly from the ravages of the war. Unlike other plantations in that part of Tennessee, it had not lost all its stock to armies or raiders, partly a result of the family having ingratiated itself with the Union army officers who made Belle Meade their headquarters. “The horses taken did not include any of Harding’s valuable brood mares,” Wills writes. “In his report, the officer said the mares were exempted from impressments until the ‘will of government’ was known.” Breeding operations resumed rather quickly after the war. General William Jackson began to assist his father-in-law, General Harding, in operating the plantation and, most especially, the horse-breeding endeavors.8

Belle Meade plantation, near Nashville, rivaled Woodburn in the production of Thoroughbred racehorses. It resumed its horse-breeding operation soon after the Civil War. The main residence was the iconic Southern horse farm. (Photograph by the author, 2008.)

In central Kentucky, the war had greatly compromised livestock breeding operations. Robert Aitcheson Alexander wrote from Woodburn to his brother, Alexander John Alexander, in 1864:

The sale was almost a failure from the fact that the Covington [KY] Railroad was not repaired so as to allow trains to run through (a bridge having been destroyed by [John Hunt] Morgan) and the fear of the men from the more Northern States that a raid would cut them off or they might not be able to get their stock away. There were only 3 or 4 men here from across the [Ohio] river and only one purchase.

The sheep brought more money than anything else…. I sold no trotting stock. Twelve head of thoroughbred later brought 3180 or 265 a head and 11 head of mares and fillies (Thoroughbred) brought 2270 or 206 each. I sold a Lexington mare out of Kitty Clark for $1000….

I am by no means satisfied with the condition of things here but cant [sic] do anything to change my stock from Ky till I go to Chicago.

In another letter to his brother, Alexander wrote in 1865: “I have got my colt brother to Norfolk back from the guerillas, but man owning him having been captured. I had to pay the captor $500 but as the horse seemed little the worse for the long sojourn amongst the rascals except in condition I am well satisfied to get him at that rate.”9

As in Tennessee, central Kentucky breeders restarted their bloodstock operations as well as they could, under the circumstances, in an attempt to join the new market. Quite quickly, they realized that they might be able to expedite the process if they received state aid. Governor Thomas E. Bramlette readily supported the growing horse industry and chartered a cooperative association that organizers named the Kentucky Stud Farm Association. Alexander and others leading this initiative included William S. Buford, F. P. Kinkead, and Abraham Buford of Woodford County, and Benjamin Bruce, John Viley, and James A. Grinstead of Fayette County. All were among the leading livestock breeders in central Kentucky. They intended for the association to develop its own breeding farm along the lines of the national stud in England. The English stud operated on an egalitarian principle, providing equal access to stallion service for all owners of mares.10

Organizers in Kentucky intended the association to provide members with the means to recommence their livestock breeding, no small matter considering that many had ended the war facing the loss of breeding stock, farms, and their labor pool, which, in most cases, had been their slaves. The group planned to purchase a farm, although there is no evidence that the plan ever got this far. The intention was to fit out the farm with paddocks and stables for horses, making it suitable for the raising of Thoroughbreds. The group also intended to purchase broodmares and at least one stallion, with the intention of auctioning the offspring when they reached the yearling stage. The Kentucky General Assembly and the Kentucky Senate chartered the new organization on January 26, 1866, and waived the customary incorporation fee of $100. Apparently, the state legislature perceived the need to support and accelerate the start of this group’s work. The Kentucky Stud Farm Association must have seen the need to help all breeders by providing easy access to a stallion and mares. Unfortunately, there is no evidence that this group ever inaugurated its well-intentioned program.11

The association’s charter clearly noted that the war had made necessary the formation of this group, stating: “The injurious effects of the late war have been most seriously felt by those who have been engaged in the breeding and raising of horse stock.” Alexander’s Woodburn had not been the only farm raided. General Abe Buford, Alexander’s neighbor, had been another breeder hard-hit with impressments by the armies and theft by outlaws. “Most of the blood stock belonging to General Buford were [sic] lost and sacrificed in ‘63 and ‘64,” reads one report.12

In addition to the raids on Woodburn Farm and the Buford place, the stables of Alexander Keene Richards, Willa Viley, John Clay, Major Barak Thomas, and many others suffered devastation. Likewise, so did two large stables owned by a Union sympathizer, James A. Grinstead, that were located at the Kentucky Association track. The Confederate raider John Hunt Morgan and his men set fire to those stables. Not far from the racecourse, at Ashland, the late Henry Clay’s estate where his son, John Clay, had raised the horse Kentucky, Morgan and his men took Thoroughbreds valued at an estimated $25,000. Among these was the highly prized mare named Skedaddle. If Clay had not chosen to take Kentucky northeast to sell in 1863, he might have lost this colt as well. John Hervey, in his history of racing, wrote: “The idea that Kentucky did not suffer more than negligible damage to her thoroughbred interests by the war is … wholly erroneous. Its ravages, of which those committed by [General John Hunt] Morgan were the most terrible, affected her best blood and finest individuals.”13

As Kentucky’s horse breeders began to regroup and rebuild, they faced problems different from those experienced farther south in Tennessee. In Tennessee, the gentry class of landowners relied on its own resources to become a self-sufficient breeding business once more. Kentuckians, on the other hand, were intent on attracting outside capital investment to their business of breeding and raising horses. The Kentucky idea held considerable potential for expansion but, from the start, proved difficult to carry out. Northern capitalists viewed investment in Kentucky after the war as highly problematic. Kentucky’s expanding reputation for violence and lawlessness led to the fear that bloodstock, farm property, and, most of all, people were unsafe in central Kentucky. Southern states on the whole had quickly acquired a notorious reputation for lawlessness after the war, but newspapers in the Northeast frequently singled out Kentucky. One Northerner stated that in no way could New Yorkers “live and safely conduct business in any section of the South.”14

The other problem was the farm labor pool, which evaporated in the months following the war’s end. Without a labor pool, the farms could not function. The farm labor pool before the war had consisted largely of slaves. Even before the war had ended, slaves had begun to enlist in the U.S. Army or flee to army camps, hoping to receive protection. After the war, freedmen fled in great numbers to Lexington and Louisville, seeking employment as well as safety from the violence they soon began to realize would be their likely fate in the rural areas. The Ku Klux Klan or vigilantes assuming the name of the Klan were terrorizing and killing black folk throughout the Bluegrass countryside. This environment could hardly have appealed to any capitalists from outside the state who might have considered locating a breeding farm in central Kentucky or, at the very least, boarding their bloodstock there.

Adding to the labor problem was the confusion over slavery and freedom: where did one end in Kentucky and the other start? The status of slaves as freedmen remained uncertain in this border state because Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 had freed only those slaves in rebel states. Slaveholding Kentucky had not gone through the war as a rebel state. Kentucky had remained loyal to the United States after a brief period of neutrality, sending 50,000 Kentuckians into the Union army. Another 25,000 Kentuckians had chosen to enlist in the Confederate army, leading to some confusion about which side Kentucky actually supported. The real story about the war from the perspective of Kentuckians, however, was the number of men who did not enlist in either army. A total of 187,000 Kentuckians chose to stay out of the war, as John Clay had. They simply stayed at home. As William W. Freehling suggests, those numbers told much about the way Kentuckians essentially regarded the war. “Those figures placed Kentucky last among southern states in percentage of whites who fought for the Confederacy and first in percentage of whites who fought for no one,” Freehling writes. Small wonder, then, that many remained confused about the status of slavery during and after the fighting since government policy concerning slaves was turning out to be different in Kentucky than in the South.15

To complicate matters, some 23,000 black Kentuckians had joined the Union army late in the war, on a promise from the U.S. government that they would be granted freedom for themselves and their families. But slavery itself was not outlawed in Kentucky with the close of the war. That would not occur until the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment in December 1865—an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that Kentucky’s legislature actually refused to ratify. Many Kentuckians who had owned slaves gave them up only reluctantly and with a great amount of resentment toward the federal government. Numbers of slave owners also refused to honor the federal law that granted freedom to black soldiers who had enlisted with the Union army. “Whatever their status, Kentucky’s black population received contradictory advice,” writes Marion B. Lucas. “Federal officials proclaimed their freedom; slaveholders considered them fugitives.” The way slavery finally ended in Kentucky was with the Thirteenth Amendment becoming law and federal troops making sure the law was enforced. As a result, whites took out their anger on blacks, many of whom fled for the cities or the North. The turmoil resulting from this situation left the farms without much of a labor force to work the fields or tend to bloodstock and livestock.16

With the status of former slaves in flux, the labor pool largely vanished on the farms and at the racecourse. A new racing periodical, Turf, Field and Farm, published in New York, recognized this problem during its first month of publication in August 1865, noting: “We fear the unsettled condition of labor in that state will interfere to a great extent with trainers in getting the right kind of hands for stable purposes.” The import of this statement, coming from a periodical published by two Kentuckians named Sanders and Benjamin Bruce, whose financial backing came from Woodburn Farm, cannot be underestimated. It appeared as though Kentuckians were sending up a white flag on the labor crisis. “Prewar production capacity was only slowly reestablished,” according to Peter Smith and Karl Raitz.17

White landowners throughout the South exacerbated the labor crisis by harassing freedmen; border-state Kentucky also experienced this trend. “Whites were obsessed with subordinating the newly freed blacks, and looming racial turmoil would make southern labor unproductive and unreliable,” Edwin Burrows and Mike Wallace write in their history of New York.18

Two months after its inaugural issue, in what was undoubtedly a public relations ploy, Turf, Field and Farm attempted to paint the labor situation in a more positive light. It reprinted an article published in the Louisville Journal that attempted to point out Kentucky’s “many advantages to the Northerner proposing to settle in the South.” The article extolled “the celebrated ‘blue-grass region’” of the state and its agricultural advantages for beef cattle, sheep, and horses, noting that “the flesh of the beef cattle and the sheep of that region possess an exquisite flavor and tenderness unknown to the leathery meats of other States.” As mentioned, the Journal agreed with the well-received belief concerning the superiority of Bluegrass soil, ascribing its advantages to the “blue limestone” underlying the region.19

The article also argued against the possibility of a protracted labor problem by predicting a bright future for free labor somewhere in Kentucky’s future, anticipating “those 100,000 slaves who yet remain in bondage, liberated, and the trained labor and skill bestowed upon the fair fields.” The author of this article did see Kentucky’s future grounded in agriculture and not in industry, however, writing: “As a manufacturing State, probably Kentucky will not, for some time at least, attract much attention.” But, in a direct appeal to capitalists who might be enticed to purchase farmland or horses within the state, he pointed out that two wealthy Kentuckians—Robert Aitcheson Alexander and Brutus J. Clay, the latter the owner of a vast cattle farm called Auvergne in Bourbon County—were men of cultivated manners who had spent great sums of money on their livestock. The problem was that the Northeastern capitalists were not inclined to wait for this ethereal future to take shape. Thus, they began building their own horse farms in New York and New Jersey. Meanwhile, Kentucky horse breeders “were faced with the problems of rebuilding the productivity of their land and of maintaining a genteel way of life without a reliable source of labor,” as Smith and Raitz have written. Thomas Clark also noted: “The shortage of labor on the postbellum estates was so critical that at one point a widespread campaign was launched to encourage foreign laborers, including Chinese coolies, to settle in Central Kentucky.”20

Bluegrass landowners then hit on an idea to encourage former slaves to return to agricultural work. They made small plots of rural land available, either without charge or at greatly discounted prices. They customarily sectioned off these portions of land at the rear of their estates away from public view, thus completely changing the landscape from its appearance under antebellum practices, which saw slaves occupying cabins within sight of the main residence. But much had changed with freedom, even the landscape. The point was that the landowners were offering laborers an opportunity to live on land that they could call their own. The labor problem did, in fact, sort itself out somewhat as a result of these rural hamlets. Smith and Raitz have suggested that the central Kentucky horse-farm landscape might never have evolved as it did into a collection of park-like estates had not the landowners provided laborers with access to land of their own and, thus, a place to live near the farms where they worked. Still, even after landowners initiated this practice, the farm labor problem did not immediately resolve itself. Two years later, Turf, Field and Farm continued to report on the labor problem, noting that hemp and tobacco production had fallen off “owing to the derangement in our labor system.”21

By 1867, labor problems continued to plague the farmlands of central Kentucky. Offering a suggestion, Turf, Field and Farm reprinted an article from a Northern newspaper, the Philadelphia Sunday Mercury, extolling the appeal of Asian workers. This article cited physical and social characteristics of Asians, in particular Chinese immigrants, that landowners perhaps would find more appealing than those ascribed to ex-slaves: “The Coolies are interesting to a foreign observer who remembers that they have come from the land of Vishnu and Brahma, the ancient seat of wonderful civilizations, where the Ganges is a god…. The men are mostly very handsome and graceful, well formed and supple, with olive skins, straight features, white teeth, long, silky black hair, and lustrous dark eyes, full of passion.”22

Turf, Field and Farm reflected the popular thinking of these times—and the labor concerns of farm owners—in citing racial characteristics and superimposing stereotypes on a hierarchy of labor. In an article titled “The Five Races of Man” published in 1867, it intoned: “Race is established by climate and mode of living … with differences so strongly determined that they are perpetuated hereditarily…. The very characteristics which form the Caucasian variety and which separate it from the varieties give it intellectual prominence … [and] make it the superior of all others.” This argument neatly ordained that blacks belonged in the fields and the stables and not in mainstream society living as the equals of whites. It mirrored the arguments that Southerners had put forth before the Civil War when they had justified slavery with patriarchal notions. Antebellum Southerners convinced themselves, and tried to convince outsiders, that they stood as the heads of their plantations and gave orders for the good of their slaves, much as a father stood as the leader of his wife and children.23

The depleted labor pool continued to pose problems for Kentucky farms, despite the effort to develop rural hamlets. By 1871, some counties, including Fayette, in the heart of the Bluegrass region, attempted to interest white labor in farmwork. At the same time, some people felt that Kentucky would be better served by the voluntary emigration of blacks to Africa—a timeworn argument seen as the clear way to remove blacks from American society. Henry Clay, an antebellum patron of Thoroughbred racing and breeding in Kentucky, had patronized this movement decades before the Civil War. Six years after the war, Kentuckians continued to debate the colonization movement. A letter published in the Frankfort Tri-Weekly Yeoman in 1871 extolled the appeals of Liberia, describing that African country as possessing “every luxury.”24

No one appeared to have found the solution for launching a Kentucky horse industry with the scope and scale that would make it competitive with the racing and breeding operations of the wealthy men who were embracing the Northeastern turf. The depleted labor pool, the depleted numbers of bloodstock, and the simple lack of wealth needed if Bluegrass Kentuckians were to compete with the industrial and Wall Street wealth of New Yorkers made the prospect appear grim. Those bookend regions of the Bluegrass, Kentucky and Tennessee, both bore the burden of these postwar encumbrances.

Kentucky and Tennessee consequently entered the new world of postwar racing and breeding at a disadvantage. Nonetheless, some differences in the way in which breeders in these two states sought to regain their niche as horse country became apparent almost from the start. Almost immediately, Kentuckians sought outside capital investment. Tennessee breeders seemed content to work with what they had. These different approaches would determine the individual futures for these Northern and Southern sections of the Bluegrass, for, by the early twentieth century, central Kentucky alone would become known as the Bluegrass. By that time, Kentucky had secured outside capital, had developed a professional class to manage the horse industry, and had avoided the antiracing laws that shut down the sport forever in Tennessee. The Southern portion of the Bluegrass posed a cautionary tale: the death of racing led to the end of the breeding farms in Tennessee. The result was that Americans soon forgot that Middle Tennessee at one time had shared the Bluegrass region with central Kentucky.

Kentuckians continued their struggle with the new world they faced after the war when Bluegrass horse country took another blow. This was the death of Robert Aitcheson Alexander in 1867 at the age of forty-eight. He died at Woodburn on December 1, following some years of poor health. He had long been known to be “feeble.” Three weeks before his death, he fell ill, then rallied briefly before relapsing. Turf, Field and Farm summed up his passing as “an irreparable loss to the country.” This estimation was not exaggerated, at least as far as horse racing and breeding were concerned. Bluegrass Kentucky especially would feel the loss of Alexander, for his death left a leadership void. None among Bluegrass landowners had proved the visionary that he had been in assembling the finest stallions on the most elegant, efficient farm before the war, then in spearheading the recovery of horse breeding in Kentucky after the war. Moreover, he had possessed the financial fortune to carry out his visionary ideas. His vision, combined with his fortune, had ensured Kentucky’s place as central to horse breeding before the war. He was only beginning to pull the breeding business out of its postwar malaise when he died. Now the question became one of who, if any, would take his place.25

Alexander’s death in fact ensured that Kentucky would take a different course than Tennessee. Kentucky’s gentry landowners learned to rely on the organizational skills and business acumen of a middle class of professionals, enabling the state’s horse business to expand, albeit slowly. More persons involved in the local industry provided the business with a wider base.

As for who would step into the leadership vacuum, the answer proved to be Alexander’s handpicked associates. Alexander’s great strength, in addition to his visionary qualities, had been his skill in delegating responsibility to individuals who, like the squire himself, saw the large picture. Alexander had groomed his trusted associates for leadership; even before his death, they proved themselves exceptional choices in their roles. Dan Swigert was one. He served as the manager of the Thoroughbred horse division of Woodburn Farm. He had worked alongside Alexander in steering the course of Woodburn; following the squire’s death, he stayed on at the farm for two more years. Then, he began purchasing his own horse farms, eventually acquiring Preakness Stud near Lexington, renaming it Elmendorf Farm. Swigert would play a key role later in the nineteenth century in linking New York turfmen with horses.26

Two more key associates of Alexander’s were Sanders and Benjamin Bruce, whom Alexander had partially funded when they established Turf, Field and Farm. In their positions as copublishers of this weekly periodical, the Bruces assumed roles as arbiters of the turf. North and South, Americans respected the two brothers for their ability to select top-choice racehorse prospects, for their auctioneering talents, and for their vast knowledge of equine pedigrees.27

Sanders D. Bruce, a Lexington native, published the first volume of the American Stud Book in 1868, eventually selling his work to the Jockey Club in 1896. With his brother, Benjamin Bruce, he founded and published Turf, Field and Farm in New York. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

Class status differentiated Alexander’s protégés from the plantation owners of Tennessee who single-handedly resumed their breeding operations. Swigert and the Bruce brothers belonged to the middle class. As such, they foretold the expansion of Kentucky’s horse industry through a professional class joined in mutual interests with landowners. An expanding number of professionals began emerging in the Kentucky horse business. Middle-class folk would make their living as pedigree experts, as recordkeepers and statisticians, as journalists reporting on the turf, as jockeys recognized as professional athletes, as horse trainers acquiring similar professional status, as gamblers and bookmakers, and as owners and operators of racetracks. If they did not make Lexington their headquarters, they traveled to and from it with increasing frequency throughout the latter nineteenth century. The yearling auctions at Belle Meade attracted many visitors, including the Bruce brothers, but they came to buy, not to set up shop in the region. If nothing else, Lexington was closer geographically to the Northeastern capitalists whose investment breeders sought. But the demographics of Lexington’s horsemen also were changing to include an aggressive professional class.

Benjamin Bruce, a native of Lexington, copublished Turf, Field and Farm in New York with his brother, Sanders Bruce, then returned home to Lexington to begin publishing the Kentucky Live Stock Record in 1875. His publication later became the Thoroughbred Record and, eventually, the modern-day Thoroughbred Times. (William Henry Perrin, History of Fayette County, Kentucky [Chicago: O. L. Baskin, 1882], 147, in possession of the Lexington Public Library.)

Periodically, the Bruce brothers served as auctioneers at the yearling sale at Belle Meade, giving further credence to an increasing awareness that Lexington’s professional class of horsemen held wide respect among gentry horse breeders. Sanders and Benjamin Bruce dispensed advice and circulated with ease among wealthy persons, who became their clients. They did not grow up as members of an elite class, yet, as professionals, they possessed the knowledge and expertise that members of that elite class were realizing they needed to access if they were to succeed in the new postwar racing world.

The Bruce brothers had grown up in Lexington in Gratz Park, a fashionable residential area several blocks north of the city center. The Bruce family home was situated on one side of the park; on another side lived John Hunt Morgan, a friend of Sanders Bruce’s and the eventual husband of the Bruce brothers’ sister, Rebecca Bruce. The brothers’ parents, John Bruce and Margaret Ross Hutton Bruce, belonged to the upper middle class and, consequently, could afford to live in this desirable neighborhood that lent them social connections as well as respectability.

Sanders Bruce was born August 16, 1825; Benjamin was born December 19, 1827. Both developed an early passion for horse racing and for learning the pedigrees of racehorses. Sanders and Morgan at one time owned a stakes-winning horse of some regional renown called Doty. The two friends also went into the hemp manufacturing business together as well as co-owing a crockery store. Benjamin, meantime, graduated from Transylvania University in Lexington with a degree as a doctor of medicine, although he soon turned from medical practice to mercantile pursuits. The brothers’ lives took a more serious turn toward the horse racing world when Sanders acquired the Phoenix Hotel sometime before the war. Horsemen traveling through Lexington favored the Phoenix, allowing Sanders, serving as the hotel’s manager and proprietor, to expand his social and business network.28

The most opportune acquaintance the brothers made was with Alexander. Perhaps as a result of the interest these three men shared in equine pedigrees, Sanders Bruce, in particular, began to assist Alexander at Woodburn Farm, more or less as a factotum. Before the war, visitors to Woodburn Farm had noted the presence of Sanders carving the roast of mutton served at Alexander’s table on one occasion when the squire had entertained guests in his rambling, rustic home. The circle of contacts Sanders had begun making at the Phoenix Hotel enlarged at Woodburn, where he met the Northeastern textiles mogul Milton Sanford before the war. Sanford provided financial backing when the Bruce brothers, along with a Lexington horseman named W. A. Dudley, founded a commercial enterprise they called the Kentucky Importing Company. The company sent Benjamin Bruce to England in 1860 to seek out yearling fillies to purchase and send to Kentucky, where they would be auctioned as prospective broodmares.29

The Civil War interrupted the lives of the Bruce brothers and led to a situation that few in the North would have understood. The brothers actually represented the war in microcosm as it had played out in Kentucky, for they chose to fight on opposite sides. Sanders joined the Lexington Chasseurs, a unit of the state guard that generally attracted Union loyalists. Benjamin went into the Confederate army, making his way to New Orleans in the well-mounted company of the horse breeder Alexander Keene Richards. The Bruces’s sister, Rebecca, also figured in this story of Kentucky families divided during wartime: as previously mentioned, she had married John Hunt Morgan, whose destiny was to make him a notorious Confederate raider.30

The swift manner in which the Bruce brothers reunited in New York at war’s end underscored a peculiar curiosity characteristic of Bluegrass Kentuckians: they could and did set aside their philosophical differences over the war when it came to doing business, particularly the horse business. The financial backing that the brothers received for Turf, Field and Farm also revealed a combination of geographic interests that strongly reflected Kentucky’s long-standing ties with Northern business. On the one side, Alexander represented Kentucky interests in helping the Bruces set up Turf, Field and Farm. Their other backer was Milton Holbrook Sanford, who had made his fortune manufacturing blankets for the Union army during the war and was a horse owner representative of the new direction the sport was taking. Later, Joseph Cairn Simpson of Chicago purchased an interest in Turf, Field and Farm. And, in 1868, when Sanders Bruce required financial backing for volume 1 of the American Stud Book, he received assistance not only from Alexander but also from Simpson and another Chicagoan, John J. McKinnon.31

Sanders and Benjamin Bruce managed to have their new periodical up and running by the first week of August 1865, just in time to defend the honor of their benefactor, Alexander, when the rival Spirit of the Times assailed him over the Asteroid-Kentucky controversy. Considering the timing of the publication of volume 1, it might have seemed like Alexander had installed the Bruce brothers in New York with his own public defense in mind. More likely, Turf, Field and Farm represented a business opportunity for the financial backers and the publishers. The stated purpose of the periodical was to represent the horse industry. It went without saying that, to the Kentuckians involved in this venture, the interests of the Bluegrass horse industry would be represented as well. Alexander gave the Bruce brothers free rein to operate their venture, and they proved the perfect pair to carry Alexander’s vision forward. And so they began their work, promoting Bluegrass land, soil, and breeding at the critical juncture when racing stood poised to go national after leaving its antebellum regional traditions behind.32

The headquarters of Turf, Field and Farm in New York occupied this building at Printing House Square facing City Hall Park, near Broadway. The New York Tribune building stood close by. “We are now in the very midst of the leading weeklies of the city,” wrote Sanders and Benjamin Bruce, the publishers of Turf, Field and Farm. (Turf, Field and Farm, June 1, 1867, 337.)

Newly installed in New York, the Bruce brothers would have seen firsthand how the extravagantly appointed, large-scale horse-breeding operations under development in New York and New Jersey might pose competition for Bluegrass breeding interests. In this, they had an advantage most Kentucky horsemen did not, the latter being too preoccupied at home with attempting to restart their operations after the war. Turf, Field and Farm published descriptive articles about these Northeastern horse farms, welcoming their owners to the turf world in the deferential manner these moguls would have expected. At the same time, these articles could have served as a warning to Kentucky horsemen that others besides themselves planned to enter the postwar market for racehorses in a major way. Bluegrass horsemen reading between the lines would have recognized the urgent need to recenter the horse world on their own region. Meantime, the Bruces ingratiated themselves into this world of Northeastern wealth, advising the new men of the turf. They played both sides of the growing divide, which appears to have been Alexander’s purpose. For their own part, the Bruces thus enhanced their own net worth. They were business opportunists of another breed—those who went north after the war instead of south.

The horse farms of capitalists under development in the Northeast rose as elaborate testaments to their owners’ wealth, expressions of material excess far beyond the scale of the Bluegrass gentry estates. Country squires in Kentucky and Tennessee bred and raised horses on farms or plantations graced with lovely homes or even mansions. But these farms were not entirely devoted to raising horses, as were the new farms in the Northeast. Neither were they endowed with the most modern equine facilities of the like under construction in New York and New Jersey. Woodburn Farm was a marvel for its architectural practicality and park-like landscape, and it stood alone in Kentucky in this respect. But, while verdant, woodland pastures were the hallmark of Kentucky farms, material excess characterized the new farms in the Northeast.

In New York and New Jersey, men who owned racehorses stated their social standing in overt fashion. Their habit was to ensure that their elite status was “manifested in the construction of country house, rural estate, and competitive stable complexes,” writes one historian. For example, William Vanderbilt’s sixteen-stall stable in what is now midtown Manhattan included a carriage house, an indoor exercise ring for the horses, and a full city block of pasture between Forty-third and Forty-fourth streets.33

One of the first to build a farm and training center in New Jersey had been Sanford, the friend of Alexander and financial backer of Sanders and Benjamin Bruce. Of all the new moguls resurrecting the Eastern turf world, Sanford was more of a maverick than most, for he had begun a business relationship with Alexander as early as 1860. He seemed intent on buying up as many sons of the great sire Lexington as Alexander would allow. (Alexander had closed off the breeding of Lexington on the open market in 1864, limiting the stallion thereafter to the private service of Alexander’s mares. Woodburn Farm continued to sell offspring of Lexington at the farm’s annual yearling auctions, hence the accusation of Northerners that Alexander controlled the market prices of this stallion.) Sanford particularly desired to own racehorses sired by Lexington out of mares sired by another great horse known as Glencoe. This combination of bloodlines had worked well in the Bluegrass, and Sanford, out of all the turf moguls, founded his program on emulating Bluegrass practices. Alexander no doubt influenced him to great extent. Consequently, while other men of the Northeast raced almost exclusively in New York and New Jersey and, later, at Pimlico Race Course in Maryland, Sanford was racing a stable of Lexington’s offspring in New Orleans in addition to the Eastern tracks. The track at New Orleans had risen, phoenix-like, from the wartime years.34

For his racing activities in the Northeast, Sanford built a private training facility and breeding farm at Preakness, New Jersey, on property situated back in the Preakness hills. He named this country retreat the Preakness Stud Farm. Typical of the new Thoroughbred farms going up in this section of the country, Preakness Stud featured the most modern touches while also retaining a timeless rural charm.

Like Sanford, the new turf titans typically expressed nostalgia for the past in the traditional, rural charm their modern horse estates evoked. They incorporated a rural motif because they relied on these estates to provide a respite from the noise and pollution of city life. Thus, the Thoroughbred and trotting-horse nurseries of New Yorkers served a dual function. They existed in order to replenish the racing stables of their owners, and they also provided their owners with country estates where they could slip away from the city, perhaps escaping into a nostalgic idea of a life people believed had existed before the onset of industrialization.

A sporting periodical of the day expressed the essential character of these rural estates: “The thoroughbred colts graze in the meadows and sport over the lawn and, when tired of the noise of the city, the proprietor can retire to this lovely spot, and realize that freshness, peace and quietness, of which poets delight to sing, and which constitutes the charm of country life.” This was Preakness Stud in 1866. Sanford could not have escaped to the country quite so easily if he had built his rural retreat far away from New York, in Bluegrass horse country. Thus, he built his farm in New Jersey, apparently with the belief that he could realize success the equal of Bluegrass horsemen by importing Alexander’s best bloodlines into New Jersey.35

Sanford had constructed two new barns, but of greatest interest in 1866 was a facility still under construction: the training barn. This polygonal building had so many sides it was nearly circular. The interior included stalls for the horses living there and an indoor training track so that they could be exercised inside during bad weather. No one in the Bluegrass had built an indoor track; Sanford, with all his money, was running ahead of the Kentuckians with this concept.36

Sanford had arranged that water from a nearby brook would be pumped hydraulically into reservoirs. He even arranged a measure of security for the horses, stocking the reservoirs with small fish whose purpose was to control the algae but also, more importantly, to warn the horse grooms “in case of any attempt to poison the water, a precaution … borrowed from England.” But then, every phase of the very idea of those country places becoming popular in the United States had been borrowed from England. Protecting the water source was the least of it.37

Sanford’s new stud farm was one of an increasing number of such facilities in New Jersey and New York. August Belmont bought an estimated eleven to thirteen hundred acres in Babylon, Long Island, calling his country place Nursery Stud. Here, he intended to retire to stud the best horses from his racing stable. At the center of this property he constructed a “handsome modern structure” of a home with twenty-four rooms. The house stood on a rise that made the building appear “so lofty that we should think the Fire Island Lighthouse and the sea might be seen from the top of it on a clear day.” The perfectly smooth green lawn sloped to a lake of thirty acres in size. On the other side of the lake, away from the main house, Belmont built a trout-hatching pond, a farmhouse, five cottages, two silos, barns, pastures, pens for hogs and chickens, and fields for growing hay, wheat and rye—“a self-sufficient community,” remarks Belmont’s biographer David Black. Belmont also built a bowling alley behind the main house.38

Belmont’s stables for his Thoroughbreds (as distinguished from those for his carriage horses) numbered twenty-seven stalls; the Nursery Stud design included a bunkhouse for fifty stable lads, more stabling for extra horses, a trainer’s house, a gristmill for the horses’ feed, a blacksmith shop, and an indoor training arena connected to the main stables by covered walkways. The indoor track actually looked more like a conservatory, for one side of the roof was completely covered with glass. This produced pleasing aesthetic effects but also aided the horses: the increased amount of light afforded by the glass roof left no dark corners around the indoor track where horses might spook from the shadows. The surface of the indoor training course was covered with tan bark. A bank of straw five feet tall and three feet wide at the top formed an inner “rail” designed to protect the horses while they exercised. A smaller circle inside this straw rail provided room for horses working at slower exercise, giving them their own space without interfering with the horses working at faster speeds.39

The centerpiece of the Nursery Stud was the one-mile outdoor racetrack with its own grandstand, of which Black writes: “August could sit [there] all by himself if he wished and watch his horses race. August had created a village, an ideal world where he could retreat.” With country estates like Nursery Stud and Preakness Stud, Belmont and others in his class were closing themselves off from lower social classes by constructing their own spheres. Apparently, it was equally important to them that their racehorses share this private sphere.40

As an increasing number of these rural retreats sprang up close to New York, it was becoming clear that the new titans of the turf were, indeed, bypassing central Kentucky and Middle Tennessee as places to build their lavish new farms. The power shift became increasingly evident with the construction of more stud farms. The Lorillard family, moguls in the tobacco business since 1826, saw one brother, George, develop Westbrook Farm for Thoroughbreds on Long Island while another brother, Pierre, developed 1,244 acres into his Rancocas Stud in 1875 in Jobstown, New Jersey. Francis Morris, whose racing colors had been registered longer than those of any family in the United States, was another whose breeding farm was situated close by New York. Upstate in New York, a wealthy gambler and horseman named Charles Reed built a breeding farm for Thoroughbreds near Saratoga Springs.41

First came the farms; then came the breeding stallions. Kentucky had retired to the new broodmare and stallion quarters that Jerome built at his racecourse; he was followed by another horse of high quality, Jerome Edgar, whom John Morrissey, the founder of the original Saratoga Race Course in 1863, had purchased for $3,000 from John Clay. Jerome Edgar retired to a breeding career at the Valley Brook Stud on Long Island. The breeding of racehorses was expanding with each new horse retired to stud in the Northeast. One indication of this expansion was the stallion advertisements published in sporting periodicals. Stallions advertised to stand at stud for the 1866 breeding season were located in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New York, Missouri, Tennessee, Virginia, Texas, and, of course, Kentucky. The breeders of Bluegrass Kentucky had come out of the war realizing that the South’s stranglehold on the sport had been broken. Kentucky breeders now had serious competition, with the outsiders paying scant notice to the criterion everyone had formerly agreed was critical for raising a sound, fast horse: the importance of raising a racehorse in the Bluegrass.42

The Bruce brothers had promoted the magic of Bluegrass soil and water to a nationwide audience from the start of their business in New York. As we have seen, one article they published in 1865 “celebrated” the Bluegrass, praising the “exquisite flavor and tenderness” of the meat produced there. The article went on to predict a bright future in agriculture for Kentucky, especially so after the slaves were set free. It cited the state’s renown for the production of racehorses, in particular at Woodburn.43

One of Turf, Field and Farm’s most brilliant initiatives was to bring the Civil War hero General George Armstrong Custer to central Kentucky in 1871. Sanders Bruce brought the general to Lexington for the express purpose of writing glowing reports about Bluegrass horse country. Custer did not disappoint. He wrote a series of five articles in the form of lengthy letters to the editor, using the nom de plume Nomad. In his first article, he praised the beauty and functionality of the horse farms. In later articles, he doled out kind words tempered with a measure of critique concerning the quality and honesty of Bluegrass trotting matches and Thoroughbred racing. Regardless of what he wrote, Custer brought attention to horse country. For this initial visit, Sanders Bruce had arranged for a small group of horse country’s power brokers to accompany Custer through his tour of selected farms. Intent on showing him the Bluegrass at its best, this group had orchestrated every phase of the horse farm tour, in the first of several visits to Lexington that Custer was to make.44

Bruce and his colleagues had counted on Custer’s celebrity to bring attention to the Bluegrass, a tactic that the horsemen of central Kentucky would polish to perfection through a long line of invited celebrities to follow. Thus, the Bluegrass horse business must credit Sanders Bruce with inaugurating a marketing practice that has endured into the twenty-first century. Not only did most Americans recognize Custer; he also had made acquaintance with the right people in the Northeast, people who could be useful to Kentucky horsemen. He had cultivated friendships with John Jacob Astor, August Belmont, Levi Morton, Leonard Jerome, Jay Gould, and Jim Fisk, all wealthy and powerful New Yorkers whom Kentuckians would have loved to bring into their sphere within the Bluegrass. Custer would die in disgrace at the Battle of the Little Bighorn in June 1876, leading some 260 of his men to their deaths. But he did not die disgraced in the view of horsemen of central Kentucky. He had suited their purpose perfectly, marketing the Bluegrass in his articles for Turf, Field and Farm.

A November day greeted Custer when he stepped off the train in Lexington to meet some of horse country’s movers and shakers, including Sanders Bruce. The latter’s connections with Woodburn Farm remained strong and would be utilized on Custer’s tour. Alexander had died four years previously, in 1867, leaving Woodburn to his brother, Alexander John Alexander, who spent most of his time traveling. The latter did not express an interest similar to his late brother’s in the operation of the farm; Alexander’s death truly had left a vacuum in vision and power that men like Bruce had stepped in to fill. Woodburn continued to operate as the premier racehorse-breeding farm in the United States, briefly under the direction of Swigert, and then under the inspired management of Lucas Brodhead following Swigert’s resignation. Bruce had planned the tour with a visit to Woodburn as the highlight, and Custer eagerly anticipated seeing Woodburn and its breeding stock. Bruce possessed the ego and moxie to match Custer’s egocentric personality. As the publisher of articles the general previously had written from Indian Territory, Bruce knew how to manipulate this cultural icon who had emerged from the Civil War with an intriguing reputation for daring bravado, his reputation matched only by his famous visage enlivened with long, golden hair that hung from his head in generous curls. He had arranged an overnight stay at Woodburn for the general, highlighted by a visit to the renowned stallion everyone longed to meet—Lexington. As a tourist in horse country, Custer could not have asked for more.

General George Armstrong Custer, better known as an Indian fighter, also owned racehorses and hoped to purchase a farm in the Bluegrass when he retired from the military. He died in 1876 at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, riding a former racehorse he had acquired on a visit to Lexington. (Harper’s Weekly, March 19, 1864, cover, courtesy of the U.S. Library of Congress.)

Most Americans link Custer’s name to his checkered career as an Indian fighter in the West. Less well known was his great appreciation for racehorses, a passion he pursued wholeheartedly during a brief posting to Elizabethtown, Kentucky, from 1871 to 1873. The U.S. Army assigned Custer and the Seventh Cavalry to Elizabethtown, believing it was capable of accomplishing what law enforcement in Kentucky had failed to do: putting a stop to the widespread lawlessness that the Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacist groups had wrought in a reign of terror directed against Republican voters and blacks. Rather than chasing Klansmen through western Kentucky, however, Custer spent most of his time in Louisville purchasing horses for the army’s use. From Louisville’s most popular hotel, the Galt House, the trip was a mere five-hour train ride to Lexington, according to Custer’s calculations.

“I wish I could describe what delight my husband took in his horse life,” wrote the general’s wife, Elizabeth “Libbie” Custer. Turf, Field and Farm had also brought attention to Custer’s equestrian talents and admiration for horses, noting: “The General knows a good horse when he sees it and finds music in the clatter of flying feet.” Libbie Custer described her husband’s dream as owning a “Blue-grass farm with blooded horses.” She wrote how he hoped to retire to horse country following his army career. Custer loved to associate with other horsemen and could speak knowledgeably with the best of them on equine pedigrees. He had even participated in horse racing during an army posting in Texas prior to his arrival in Kentucky. During the Civil War, he had attended trotting races in Buffalo, New York, and Thoroughbred races at Saratoga. He appeared greatly pleased to visit Lexington, where the conversation, as he quoted a friend, consisted quite agreeably of “nothing but horse, horse, horse.” He observed: “[Even] the youngest boy, white or black, can correctly trace the pedigree of every prominent horse, and give the time of every prominent race, with the place of each horse. He would not be a Kentuckian of the Blue Grass region if unable to do this.”45

Custer’s first article in his series from Bluegrass country revealed his fascination with the region right from the introduction, as he wrote: “Being desirous of taking a peep at the flyers of the Blue Grass region in their Winter quarters, I stepped aboard the early train from this city to Lexington.” Two days of fine dining in Kentucky mansions in the congenial company of like-minded men awaited Custer. His hosts had arranged to meet him close by the train station at the Phoenix Hotel, where they began with a midday meal. Then the group set off in two horse-drawn carriages for Woodford County and the neighborhood surrounding Woodburn Farm.46

Two hours later, the men arrived at the residence of Benjamin Gratz, the owner of a farm adjoining Woodburn some fourteen miles west of Lexington. The group dined and spent the remainder of the evening talking about horses, a conversation topic that might have been Custer’s favorite. “The stranger is struck with the universal importance attached to horses and their history,” Custer commented. The group retired early; plans called for an early start to Woodburn Farm. Custer awoke the next morning to see a servant building a fire in the room where he had slept. Just as his article told readers much about Bluegrass horse farms, his description of this early morning domestic routine revealed how he and others of his time regarded persons of color.47

The servant, he wrote, “an overgrown fifteenth amendment, entered our room for the purpose of building a fire. Col. Cook, arousing from a comfortable slumber, and anxious to learn the hour, inquired of the girl, ‘What time is it?’ ‘Oh, de cows done gone long go.’ The Colonel, half awake, repeated his interrogatory, to which the ebony representative replied as before, ‘De cows done gone long go.’ Now as neither the Colonel or myself had ever informed ourselves at what hour Blue Grass etiquette required the cows to be ‘gone,’ we were left in ignorance of the hour of the morning. Our doubts on this point, however, were soon removed by Col. Bruce popping his head in at our door.”48

The referenced Fifteenth Amendment was, of course, the constitutional amendment granting suffrage to black men, a subject hotly debated in the North and the South as well as in the border state of Kentucky prior to ratification of the amendment in 1870. In the years to come, the debate would take on new meaning as it shifted into the sport of horse racing. At the time of Custer, however, Kentucky had refused to ratify the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth amendments, which had, respectively, outlawed slavery in the United States, granted citizenship and full protection under the Constitution to blacks, and granted them the right to vote. With Custer feeling comfortable enough to write about the servant as he did—and Bruce agreeing to publish his remarks—the two men revealed a disdain for blacks that readers of Custer’s articles apparently would not have found offensive in either North or South. Custer, a Northerner whose boyhood home was Ohio, appeared to feel no differently about blacks than did the Kentucky-born Sanders Bruce. The Civil War, which began as a fight to keep the United States together and wound up as a fight to end slavery, had been over for six years; however, blacks had gained freedom in name only and generally received little respect.

The facade of the main residence at Woodburn Farm has undergone a variety of changes. The house was built originally in the Italianate style. Robert Aitcheson Alexander never lived in this house. He lived across the Old Frankfort Pike at his family’s former log home. Colonel William Buford built the nucleus of the Italianate house on property he had purchased when a portion of Woodburn was sold. Following his death in 1848, his heirs sold the land back to Woodburn Farm. Alexander John Alexander, who became the owner of Woodburn on the death of his brother, Robert Aitcheson Alexander, made the former Buford house his residence. (Postcard from the collection of the University of Kentucky Libraries, Special Collections.)

Sanders had intended the visit to Woodburn as the highlight of the tour; he did not disappoint Custer. When Custer wrote his article, he devoted more space to describing the Woodburn operation than he did to any other farm: “The princely estate,” as he called it, “embrac[es] four thousand acres of the richest and fairest soil in the world, with its trotting stables and exercising grounds at one point, its stables and walks for runners [Thoroughbreds] at another, while midway are to be found the immense stables and pastures of the fine herds of shorthorn cattle and Southdown sheep.”49

Custer also observed Sanders Bruce making close observations, “with pencil and note-book in hand,” of the Thoroughbred weanlings intended for sale seven months later at the annual Woodburn auction of yearlings held in June. Bruce, as Custer noted, made notes on the weanlings for “his Eastern friends,” who probably would commission him to bid on these horses at the auction. Two years previously, Bruce had picked out a yearling named Harry Bassett for a racehorse owner from the Northeast named Colonel David McDaniel. He acquired the yearling for $315 for McDaniel; within two years, in other words, by the time Custer visited Woodburn, Harry Bassett had developed into a champion three-year-old racehorse. His success was bringing increased attention to Bruce and his innate talent for picking out yearling racehorse prospects. The Bruce brothers served their Northeastern clients well, working as a conduit between New York and the Bluegrass. Custer realized how this worked, with the Bruces having the ability to sell their services as go-betweens because they not only knew where to find horses but also were able to link the buyers with the sellers. Later generations would call such persons bloodstock agents. During these postwar years, the Bruces simply represented themselves as two brothers offering their services in just about any phase of the nascent horse industry. They represented the beginnings of the professional class that was only emerging in the sport, bringing order and business practices to horse racing and breeding as the two businesses embarked on their expansion. Custer’s writings helped them along their way.50

“Ah, Colonel, you’re cum to look at de colts agin, has ye. You beats dem all a namin’ de fastest ones,” remarked a man Custer quoted in his article, identifying him as “the sable old functionary” of the Woodburn stables, a man who probably was a former slave and “who has been born and bred among the thoroughbreds of Woodburn.” Black persons worked in great numbers at Woodburn, as previous visitors had observed in the articles they wrote about this large livestock-breeding operation. Depending on the job categories they filled, a few received more respect than others.51

One such man was the horse trainer Ansel Williamson, sent to Woodburn during the war as a slave on loan from Alexander’s close friend in Georgetown, Alexander Keene Richards. Williamson returned to Richards a free man late in 1865 but not before he had taken the Woodburn horses through several successful racing seasons during the war. Alexander trusted Williamson to the extent that he allowed him to travel with horses to the new Northeastern tracks during the war. Asteroid’s success on the track marked the high point of Williamson’s horse-training career. Alexander revealed the respect he had for Williamson’s ability with a horse when he named a Thoroughbred for the trainer, calling it Ansel.

A painting of Asteroid by Edward Troye shows Williamson preparing to lift a saddle onto the horse’s back while the animal’s jockey adjusts his riding boots, preparing to mount. The jockey is “Brown Dick,” a black youth whom Alexander had purchased as a slave when the boy was age seven, taking him to Woodburn to train him to become a rider. Brown Dick left Woodburn in 1869, transitioned into the role of a horse trainer, took the name Edward D. Brown, and developed two horses—Ben Brush and Plaudit—who would win the Kentucky Derby after they left his care. Custer quite possibly might have encountered Williamson or Brown Dick on his many visits to racetracks. He probably would have spoken to either with greater respect than he showed the domestic employee who stoked the fireplace at the Gratz farm because horse racing relied on the talents of black men like Williamson and Brown Dick to sustain the operation of the sport in these early postwar years. They won the respect of whites.52

Lexington’s fame as a sire, acquired during the nineteenth century, remains unequaled in the history of the turf. He led the sire list in number of winners among his offspring for sixteen years. He was purchased on his retirement from the racetrack by Robert Aitcheson Alexander for a then-record $15,000 and stood at stud at Woodburn Farm. (Henry William Herbert, Frank Forester’s Horse and Horsemanship of the United States and British Provinces of North America, vol. 1 [New York: Stringer & Townsend, 1857], facing p. 386.)

Custer described several of the trotting-horse breeding stallions he saw at Woodburn. Then he turned to the Thoroughbreds, remarking that some of the young offspring of Asteroid looked well. He also took a look at Asteroid, who was turned out in a pasture. But the horse who remained to be seen was the king of Woodburn’s horses, Lexington, the sire of Asteroid, Kentucky, and Norfolk as well as so many other Thoroughbreds whose success on the racecourses had underscored the breeding prowess of their sire. Custer reacted to his audience with Lexington as though laying eyes on a king.

“As his groom drew back the bolt and opened the door which admitted us to the distinguished presence of this famous horse,” Custer wrote, “we involuntarily felt like lifting our cap, and with uncovered head and respectful mien approach this great steed as if we were in the sacred presence of royalty.” Lexington had long ago lost his sight. Custer noted that, instead of the horse turning to look at his visitors, as any horse with eyesight would, the blind stallion relied on his hearing to reveal the presence of Custer and the others at the door of his stall. “Lexington assumed an attitude of intent listening,” Custer wrote, “pricking his ears as if to determine by the sounds of the voice who we were and the occasion of our visit.” A handler led the great horse out of his stall, removed the animal’s blanket, and stood the horse for further inspection. After pausing here to enjoy the moment, Custer and the group moved on to inspect two other Thoroughbred stallions, Planet and Australian.53

Much more awaited Custer. Bruce and the Woodburn manager, Brodhead, had arranged for the general to dine in the mansion. The new owner of Woodburn, Alexander John Alexander, happened to be traveling to California and so was not present; Brodhead served as host. “Gen. Custer” and his group “spent a day and night with me last week and seem to be well pleased with their visit,” Brodhead would write to Alexander in one of the letters he routinely sent the owner of Woodburn to update him on the daily workings of the farm. Brodhead, like Bruce and Swigert, represented the emerging professional class that was taking on important functions in the world of fast horses. He had “supreme control of Woodburn Stock Farm and its valuable herds and stables,” Custer remarked. His filling this role enabled Alexander to travel and live his life largely as an absentee owner—a lifestyle that remained uncommon in the Bluegrass at this time but by the turn of the century would become the norm. Brodhead, as Custer wrote, played out his role in a polished, professional manner and “received us with that marked courtesy and cordial hospitality which has ever characterized the proprietors of this justly noted establishment.” He might have been alluding to the former owner, Robert Aitcheson Alexander, who remained on the farm much of the time and greeted visitors himself. But times had changed at Woodburn, as they had changed in all of horse racing.54

Bruce, working in tandem with Brodhead, had intended for the dinner at Woodburn to impress Custer every bit as much as his visit to the great estate. Mentioning the mansion in his article—for the new owner of Woodburn had chosen to live in a grander house than the former log cabin that Robert Aitcheson Alexander had occupied across the road—Custer went on to describe their meal. “Two items—important ones, too—I must mention,” he wrote. “A piece of Southdown mutton, served in the perfectness of Southern style, and Alderney milk of such rare and exceeding richness as to cause one only accustomed to city living to wonder whether he had ever really tasted pure milk before.” The milk and the mutton would have come directly off the farm, for Woodburn raised these specifically named sheep and cattle. The meal suggested more of the richness indigenous to the Bluegrass that Custer already had noted in his tour of the Woodburn stables and grounds.55

The remainder of Custer’s tour went pretty much the same, with an impressive orchestration of showing the finest Bluegrass farms and winding up with another night spent in a Kentucky mansion: this time at the McGrathiana farm of Hal Price McGrath. The fortune that McGrath had built from running gambling houses in New York with his close friend Morrissey had enabled the Kentuckian to engage in a far more expansive way in horse racing and breeding. Kentuckians and many others knew him as a man of great hospitality; a stop here during the farm junket was a must for Custer and his party.56

Custer, appropriately charmed, wrote how they sat down to “a champagne supper, which Delmonico [the famed New York restaurateur] could not have excelled. In keeping with his deserved reputation for hospitality, McGrath also opened up his stores of bourbon for the enjoyment of those assembled. As Custer wrote: “There were some choice spirits there besides those which were bottled.” He mentioned some who had attended, including a “turf” writer, Joe Elliott, of the New York Herald, who was en route to New Orleans to write about the races in that Southern city. Another he named was a Colonel Morgan, the brother of the late General John Hunt Morgan—“of Confederate fame,” as Custer noted. Just as the Bruce brothers had reunited to forget their political differences after the war, so had some notable horsemen, businessmen, and landowners of the Bluegrass. Former Confederates could feel comfortable in the presence of a Union army officer. Their host, McGrath, had not fought in the war, choosing like John Clay to pursue his business interests instead. For McGrath, these interests had consisted of running his gambling rooms from New Orleans to New York. “A jolly old soul was he,” Custer wrote of McGrath, but the point was this: when it came to selling horses or promoting the idea of Bluegrass horse country, ex-Confederates lined up alongside former Unionists to accomplish their purpose in Kentucky.57

Custer departed central Kentucky following this whirlwind tour, returned to the Galt House in Louisville, and wrote the first of his five dispatches about his impressions of horse country. Bruce, as his host, had executed a perfectly planned marketing ploy in persuading the general to write these articles for Turf, Field and Farm, for Custer was promoting the notion that the Bluegrass had not lost the natural qualities that had made it the source of sound, fast horses before the war. If the Bluegrass had two qualities that no other region possessed, it was the abundance of superior Thoroughbred breeding stock and the unique land these horses grazed on. The soil of this rich land had made the Bluegrass in the beginning; promoters like the Bruce brothers were working hard to fix this idea securely within the imaginations of the nation’s wealthy sporting men.

The marketing plan that Robert Aitcheson Alexander had envisioned with his financial support of the Bruce brothers was moving in the direction he had hoped prior to his death in 1867. Alexander had forfeited one opportunity when he failed to send Asteroid to race Kentucky. Seizing another chance, Alexander did not fail a second time. The results he set in motion by financing the Bruce brothers in their ventures would aid the Bluegrass greatly in reinforcing the notion that this region was America’s true racehorse country. Nature’s work here, begun some 460 million years before Asteroid and Kentucky raced onto the stage, benefited horses in ways that the fad for Northeastern farms could not possibly match. But it would take Northeastern turfmen another thirty years to fully realize this.