Longfellow was only beginning his stud career in 1873, still keeping his name and the Bluegrass region in the news, when another Kentuckian started down a career path that would bring a similar attention to this place and to notions of who and what Kentuckians were. This was Isaac Murphy, an African American born during the Civil War and raised in Lexington. His destiny was to make him one of the most successful jockeys of all time, one of a handful of riders who helped elevate the significance of their profession from laborer to athlete. During a time when the owners and trainers of racehorses were only beginning to recognize publicly the key role that jockeys played in the success of these animals, Murphy in particular showed that a black man from former slaveholding Kentucky could win financial wealth, the respect of whites in his home state, and respect as a star athlete in New York, where white jockeys were more commonplace. Like Longfellow, like Harper, like Woodburn Farm and Asteroid, Murphy became an icon of Bluegrass horse country. Unlike the others, his place in the pantheon of Bluegrass leaders endured over no more than a limited period of time.

His career path paralleling the success of Longfellow, Murphy was by the late 1880s arguably the leading jockey in the United States, with newspapers and sporting journals lauding his success. Longfellow reached his apex as a breeding stallion in 1891 with wide acclaim as the leading sire in terms of number of winners that year on North American racetracks. All memory of John Harper’s authorized mock lynching at Nantura Farm during Longfellow’s racing days lay forgotten in the flush of the horse’s success as a sire. Meantime, in a generous display of good feelings indicative of fluid racial relations, Americans overlooked Murphy’s wild boast that he made more money in a year than U.S. president Benjamin Harrison’s cabinet members. To most, it did not seem to matter that Murphy, a black man, revealed a certain arrogance in making this bold statement.1

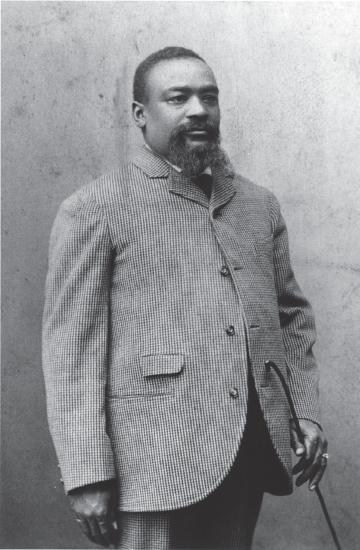

The Hall of Fame jockey Isaac Murphy, a resident of Lexington, won the Kentucky Derby three times. He ranks as one of the most successful jockeys of all time; his record of winning 44 percent of his races has never been matched. He is shown here, the only black man among whites, attending a clambake held in New Jersey in 1890 to celebrate Salvator’s victories. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

Earning at least $20,000 annually, Murphy indeed ranked as the highest-paid athlete in the United States. Toward the end of his riding career, he also became a racehorse owner, not unprecedented for a black man because Dudley Allen of Lexington bred, trained, and was an ownership partner in the 1891 Kentucky Derby winner, Kingman. But, while turfmen continued to praise the great horse Longfellow for generations following his death in 1893, they quickly forgot about Murphy soon after his death in 1896. This occurred because, during the late 1890s, a lot changed for black men who aspired to greatness in Thoroughbred racing.

Murphy’s story illustrates how black jockeys and horse trainers who gained national prominence and respect in the sport eventually found themselves shuffled to the rear of the bus. Moreover, the sport quickly wiped from memory all that they had achieved in the way of personal success during the post–Civil War expansion of horse racing. Murphy was not the only black horseman denied a place in the narrative of Thoroughbred racing as it would be told for the next fifty or sixty years. Yet, as the jockey whose career record of 44 percent winners remains untouched, the erasure of his story was the most remarkable development in the sport’s narrative.2

Murphy did not live long enough to see black horsemen denied prominent positions in the sport. He might, however, have suspected that this shift lay just over the horizon. In 1890, the Northeastern moguls who owned Monmouth Park in New Jersey temporarily banned him from that racecourse for a questionable ride on a horse that might or might not have occurred through his own fault. Northeastern newspapers that had consistently praised Murphy for his outstanding talent and his qualities as an upright citizen turned on the jockey as though they had never written a good word about the man. Stories began to surface about his consumption of large amounts of alcohol, and, in fact, his contemporaries believed that he was drinking to excess, for authorities suspended him on this account at the Latonia Race Course in northern Kentucky, near Cincinnati. But during an age when white jockeys similarly consumed a great amount of alcohol—this was part of the regimen for recovering physical strength after sweating off pounds in the sauna—Murphy emerged as the scapegoat.3

The turning point for black horsemen came with the rising racism in Northern cities like New York and Chicago. Black horsemen had never dominated in numbers at racetracks in the North, as they had in Kentucky and the South, but Northerners had afforded them a professional respect. However, the Northeastern moguls of the turf who had changed the sport so radically brought cultural changes that eventually began to affect Kentucky racing as well. Northeasterners were sufficiently powerful to alter the face of the sport from one of mixed races to one of entirely white faces.

Edward Dudley Brown, born a slave, went from winning the Belmont Stakes as a jockey to winning the Kentucky Derby as a horse trainer. He also developed two more horses that would go on to win the Derby for other racing stables. He was elected into Thoroughbred racing’s Hall of Fame. He also owned racehorses. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

“These new people, meaning New Yorkers, Northerners, who have barged in and taken over much of the breeding, don’t understand the Negro, say the veterans,” reads one explanation of this cultural turn. As a consequence, the turf began to forget about its famous black horsemen: champion jockeys like Willie Simms, James “Soup” Perkins, Shelby “Pike” Barnes (the national leader in number of wins in 1888), Tony Hamilton, Monk Overton, George “Spider” Anderson, and Oliver Lewis (winner of the inaugural Kentucky Derby in 1875), and trainers like Ansel Williamson (the winner of the inaugural Kentucky Derby), Ed Brown (widely respected in both North and South as a horse trainer), and William Walker (who held an important position at Hamburg Place, advising the owner of the farm, John Madden, on which sires would be most suitable to breed to the Hamburg Place mares).4

White turfmen, who by the early twentieth century had assumed all the power in Thoroughbred racing, wiped from the sport’s collective memory all recollection of black horsemen. They accomplished this by choosing to ignore the significant role that African Americans had played in developing a national profile for the sport. The outcome disclosed still another way in which the epicenter of power in Thoroughbred racing had shifted almost entirely to the Northeast, the influence of which was affecting cultural practices in horse racing everywhere.

Murphy’s story would remain stricken from the sport’s narrative until one bright Sunday morning in March 1961, when two men searching the grounds of a cemetery in Lexington discovered the jockey’s grave site. Eugene Webster and Frank Borries Jr. pulled back the weeds hiding a small, crumbling concrete marker identifying the site. The moment marked the beginning of a major turn: the rediscovery of a past in Thoroughbred racing in which black horsemen had played highly significant roles in developing the sport.

Borries had learned about Murphy while reading old sporting publications. Finding the grave had become his obsession. But, after more than three years of searching, he had experienced no luck until meeting Webster, a resident of the neighborhood surrounding the African American Cemetery No. 2 on East Seventh Street. Webster told Borries he knew the location of the grave.

The story about the lost grave illustrates how effectively white patrons of racing had written highly successful black men out of history. This March day in 1961 actually was the second time Murphy’s grave had been rediscovered. Thirteen years following Murphy’s death, the same Eugene Webster had taken some concerned horsemen from the Kentucky Association track to the jockey’s grave. According to what Webster told Borries, the horsemen, presumably black, had heard that a wooden marker at the grave had disappeared. They wanted to replace it so that the site would not become forgotten. They sought Webster’s help because they did not know the location of the grave.5

In 1909, Webster had been able to show the way to the site because his father, Richard Webster, had taken him there many times. Once he and his companions arrived at the site, the horsemen poured a concrete marker there. But, according to Webster, they did not know how to stamp Murphy’s name into the concrete. Therefore, they left the new marker in place without a name to connect it with the jockey. Until Webster took Borries to the site in 1961, the grave and marker had lain forgotten in the tangle of weeds that overtook the African American cemetery after years of neglect.

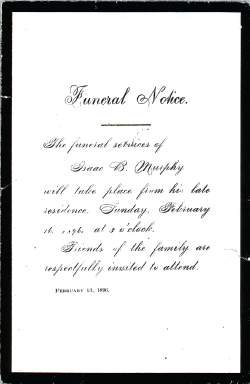

The loss of local knowledge about the location of the grave or even about Murphy seems ironic given that the jockey had been a national celebrity as well as a local hero. Newspapers had devoted a great amount of coverage to his funeral in 1896 and the large procession that accompanied the casket through the city streets. Turf, Field and Farm had described the procession as “the largest funeral ever seen at Lexington, Ky., over a colored person.” This information might have been incorrect—thousands of persons had attended services in 1854 for a black minister named London Ferrill. The numbers must have seemed impressive, however, and among those in attendance were such white dignitaries as Colonel James E. Pepper, the owner of a horse farm in the Bluegrass, and James Rodes Jewell, a prominent local judge. Murphy’s family sent out engraved invitations to the services. Jockeys, horse trainers, and horse owners sent floral arrangements. Lincoln Lodge No. 10 of the Colored Masons, a group to which Murphy had belonged, adopted a resolution declaring that “the community has lost one of its best and most successful citizens.” The lodge also recognized him as a model man of the Victorian Age, noting that “a faithful and loving wife has lost a discreet and devoted husband.”6

Isaac Murphy’s grave site became lost in the weeds at the African American Cemetery No. 2 in Lexington. Eugene Webster (shown here) and Frank Borries Jr. rediscovered it in 1961. Murphy’s remains subsequently were moved twice: first, to the original location of the Man o’ War memorial on Huffman Mill Pike, then to the newer site of the Man o’ War memorial at the Kentucky Horse Park. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

The well-attended funeral had seemed only fitting at the time. As one of the leading athletes in the United States, Murphy had risen to a position that enabled him to dictate the terms of his riding contracts to the wealthy men like mining kings, wizards of Wall Street, and robber barons who were taking control of the turf. Admittedly, his ability to negotiate on equal terms with these tycoons represented a marked departure from the experience of the average African American, but he was a star in the emerging postwar world of sports. He wore his fame with dignity and was renowned for his honesty in a world of jockeys where the majority possibly were not the most honest of souls.

Murphy was born in 1861, a free black, on the farm of David Tanner near Lexington. Originally, he used the surname of his father, James Burns, who died at the Union army’s Camp Nelson, south of Lexington, in Jessamine County, during the war. Murphy’s mother, America Burns, took the boy to Lexington, where they lived with her father, Green Murphy. Soon after Isaac began riding winners at the racetrack, he took his grandfather’s surname.7

Murphy’s riding career developed within a larger world greatly conflicted about the place that African Americans were to occupy as new citizens. For a short time, perhaps a few decades, Thoroughbred racing appeared willing to give space and recognition to talented black athletes. This placed black horsemen on an exceptional plane, differentiating their lives from those of most other African Americans. For, even while black jockeys and horse trainers received praise and respect for their work, the average African American faced frightening times, both in the border states and in the South. African Americans in the North faced discrimination and segregation even if whites did not subject them to the extreme violence more peculiar to the former slave states. Northern whites welcomed freedom for blacks in principle only; the reality of seeing increasing numbers of blacks flee Southern states for the North was repugnant to great numbers of Northerners and a reality that they had not considered until the war ended. Throughout the South and border states like Kentucky, whites no more equated equality with freedom from slavery than did Northern whites. African American horsemen like Murphy were the exception, arguably because they served a purpose in rebuilding horse racing after the war.8

An engraved notice of funeral services in Lexington for Isaac Murphy in 1896. A large crowd accompanied the funeral procession through the city streets. White dignitaries attended, and jockeys, owners, and horse trainers sent flower arrangements. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

The reality of the newfound freedom from servitude in Kentucky, as in the Southern states, was simply a transition to another form of subservience in which whites expressed a firm determination to maintain racial and, therefore, social control. The personal brutality that had characterized the master/slave relationship transformed quickly after the war into lynchings and mob violence. George Wright has written that “white violence became so widespread that many of the northern freemen’s aid societies that operated in other former slave states, helping the blacks in the transition from bondage to freedom, avoided Kentucky for fear of the lives of their workers.” Whites forced numerous blacks to leave Kentucky, and many of those blacks went north or into the West. Wright saw evidence that blacks who achieved financial prosperity attracted violence as they “threatened the entire system of white supremacy.” John Harper’s authorizing a mock lynching at Nantura Farm in 1871 suggested how strong the desire was in the Bluegrass to retain white supremacy. The timing of his action was significant. It occurred in the wake of political and social changes that were challenging whites’ position.9

Emancipation had wrought seismic changes in the social fabric of Kentucky, and whites were not acquiescing willingly to the new social order. They found it repugnant not only that former slaves enjoyed freedom but also that, with the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment (February 3, 1870), these freedmen had gained the right to vote. The notion of blacks voting shook the very foundations of the ideology that whites had promulgated in order to justify slavery: that blacks were savages unfit for citizenship, most especially in a nation founded on republican ideals of self-government. White Kentuckians took up the cry of their neighbors to the south. They argued that the amendment was a fraud forced on decent American citizens in violation of the U.S. Constitution. Aaron Astor has inquired into this outrage over the Fifteenth Amendment, studying its effects specifically on the first-ever biracial elections in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, during August 1870. Astor quotes an article from the Harrodsburg (KY) People: “[The Fifteenth Amendment] forced to the polls a vast horde of men, utterly ignorant of the duties and responsibilities attached to the new position into which they had been thrust by the bayonet and by congressional corruption.” A riot broke out in Harrodsburg, resulting in the deaths of both black and white men.10

Astor is among a cluster of historians who are beginning to take seriously the old saw that Kentucky seceded from the Union only after the war was over. His inquiry, uncovering a visceral opposition to the Fifteenth Amendment, gives credence to this reoccurring popular notion. Arguably, nineteenth-century white Kentuckians did find this amendment so repugnant and so threatening to white supremacy that they began to believe that the South had been right all along in seceding from the United States.

Along with Anne Elizabeth Marshall and Luke Harlow, Astor represents an emerging group of historians who have argued that this postwar epiphany for white Kentuckians evolved into a Confederate identity for the state. These three have drawn their conclusions in different ways, but the result has been a more nuanced look at how and why Kentuckians from some sections of the state, including the Bluegrass, saw themselves as Confederate and Southern to a greater degree following the war. At one time, historians thought that they saw this same metamorphosis, but they explained it as resentment over atrocities committed in Kentucky by the U.S. Army during the war. Astor, Harlow, and Marshall have found that widely dispersed resentment over the fall of slavery in Kentucky lay at the root of this change of mind.11

In Lexington, a great fear of “Negro rule” resulted in white supremacist tactics entering the political sphere. A simmering stew of resentment, discontent, and hate reached a boil in 1871, when a federal grand jury in Louisville indicted Lexington’s mayor and other city officials for their actions during a riot in Lexington over black voting. A similar stew boiled over in the 1873 municipal elections in Lexington. By this time, Democrats were waging an all-out campaign to keep Republicans out of office in the city, fearing that, if they won control of the local government, they would place black persons in authoritative positions, including those of police officers. They also feared that, if Republicans held office, they would permit black children to attend public schools.12

Democrats played on these phobias by instilling a fear of “Negro rule” in the white population. The Kentucky Gazette, the newspaper that supported the Democratic Party in Lexington, warned readers that it behooved every Democrat to vote as if his life and property depended on it. It warned that a “black canaille” was out to overtake municipal government. “The white men of Lexington are not going to permit the niggers to rule this town,” the Gazette trumpeted, as though issuing a call to arms. The election process saw white officials denying blacks the vote in 1873. As in 1871, federal authorities arrested city officials and took them to Louisville for yet another grand jury hearing. Predictably, the Kentucky Gazette expressed its outrage. “The interference of Federal authorities in the local affairs in Lexington is a gross outrage,” it declared.13

The Gazette kept hammering home the alarming implications of the black vote, pointing out what it interpreted as the increasingly threatening presence of blacks throughout the city. Not mentioned was the fact that, during the slavery era, blacks had been equally visible on city streets while performing tasks and errands for their owners. In the meantime, concern over the new biracial society became increasingly evident at the state level. Bourbon Democrats, a conservative wing of the party that represented aristocrats and landed gentry, spoke out at the Democratic convention about their grave fear of the “revolutionary Republicans” attaining their goal of black social equality and, thus, in the Democrats’ eyes, despotism in the commonwealth.14

The sociologist Gunner Myrdal would reach the obvious conclusion in the 1940s: that an American dilemma had existed since the Civil War over “what to do with the Negro in American society.” However, the white turfmen of Kentucky and the South began to agonize over this dilemma only some thirty years later. Until that time, they were not the least bit concerned about black Americans occupying important positions at racetracks; they viewed blacks as simply continuing to occupy the same jobs they had held as enslaved persons, jobs as jockeys, horse trainers, and caretakers of horses. Eventually, Northern turfmen persuaded their colleagues in Kentucky and the South to change their minds. By the early twentieth century, black jockeys found themselves unwelcome in the starting gate everywhere from New Orleans to Kentucky and on to New York and Chicago. It was as though horse owners, horse trainers, white jockeys, and the public had reached an unspoken agreement that no longer would it do to have black men sitting on flashy racehorses in the spotlight.15

In Lexington and Louisville, in New Orleans, Memphis, and Nashville, in fact, at racecourses throughout the South and the upper border states, black jockeys and horse trainers had predominated in numbers throughout the slavery era and for perhaps thirty years following the Civil War. Some former slaves, including Ansel Williamson and Edward Brown, discovered widespread fame within the sport following the war. Others, like Murphy, were born during or after the war and never knew slavery. Collectively, they formed the greatest repository of knowledge about racehorses, for the care, training, and riding of these animals had been the province of slaves in the South. Older black men mentored the young boys who apprenticed to racing stables, seeking to learn the jockey craft. Southerners and Kentuckians had been so accustomed to seeing black youths riding races and black men handling the training chores, working alongside white trainers and jockeys, that they considered this mixing of races in the horse stables to be the natural order of the racetrack.

The South’s white racing patrons also mixed freely with black spectators, for example, in New Orleans, where both races intermingled in the grandstands at the premier track, known as the Metairie Jockey Club. At least, they mingled freely up until 1871, when the Metairie course erected a separate stand for blacks. The jockeys had not been separated, however, and, two years later, the New Orleans Times was writing how “the darkies and whites [among jockeys] mingle fraternally together, charmed into mutual happy sympathies by the inspiriting influence of horse talk.” The patrons, however, initiated segregation in the grandstand, perhaps in reaction to the Reconstruction work of Radical Republicans in New Orleans. Reconstruction, wholeheartedly resented throughout the South, had been intended in part to support African Americans by upholding the civil rights granted them. The editor of the New Orleans Louisianian, a newspaper with a black readership, urged blacks to boycott the horse races at Metairie in response to the segregation of the grandstand. He argued that this separate grandstand “pandered to the ignoble passions and prejudices of those who possess no other claim to superiority, than the external shading of a skin.”16

Economic pressure forced a partial reversal of this segregation effort. When a new group called the Louisiana Jockey Club took control of the track from the Metairie Jockey Club, the operators partially reversed the earlier segregation order and allowed blacks to mingle anywhere in the grandstands except within an exclusive section located in the “quarter stretch” near the finish line. Still not satisfied, two African American patrons sued the track ownership, accusing the club of violating the Civil Rights Act of 1869 by refusing equal access to public accommodations. The suit evidently went nowhere. However, after Reconstruction ended in 1876, an amazing reversal occurred: black patrons regained the equal accommodations they previously had been accorded. For the remainder of the nineteenth century, blacks mingled freely with whites at the New Orleans track.17

In Kentucky, the sport benefited from the great numbers of African American horsemen who remained in the state after the war. These horsemen aided in the recovery of the turf in the Bluegrass since they possessed the body of knowledge about horse care and also constituted the much-needed labor pool. Jockeys and horse trainers drew attention to the sport in Kentucky with the success they achieved there and in the Northeast. But the time had not come when the sport everywhere would view jockeys as an elite class of athletes. In the view of whites, jockeys and horse trainers were no more than laborers filling jobs that whites did not want. David Wiggins, who has written on black athletes participating in the white world of sports, identified the job of racehorse jockey as one of those occupations considered fit only for blacks since it had been closely associated with slave labor. Consequently, blacks dominated this division of labor in the South after the war, just as the overwhelming number of bathhouse keepers, tailors, butchers, coachmen, barbers, delivery boys, and laundresses were black.18

The paddock scenes of black horsemen mingling with whites that patrons of the turf would have seen in the South were not the scenes that the revised narrative of racing depicted later. Still, blacks did, in fact, dominate the landscape at Kentucky racetracks. Black jockeys rode the winners of twelve of the first twenty-two Kentucky derbies from 1875 through 1896. Thirteen of the fifteen riders in the inaugural derby were black. No one in Kentucky considered this exceptional during that era, for the situation represented the norm. Northern patrons of the sport did, however, notice how numbers of blacks predominated in Kentucky racing, prompting the Spirit of the Times to remark in an 1890 headline: “All the Best Jockeys in the West Are Colored.” By the West, the Spirit as usual meant Kentucky, for it was speaking from its authoritative location in the East. The particular article in question concerned the number of black jockeys riding at the Latonia course.19

Northeastern racing did not have this longtime exposure to great numbers of black jockeys and trainers. Northern racing patrons certainly saw the occasional black rider or horse trainer during the Civil War, when Kentucky stables began going north to race. Following those years, the numbers of black riders increased somewhat in the Northeast, but blacks never dominated in numbers as they had in the Southern states or in Kentucky. Northern stables tended to pluck their jockey prospects from the labor pool most readily accessible in their part of the United States: the urban streets and orphanages, where small white boys abounded, many of them Irish. The Live Stock Record told in 1894 how this process worked. A great number of boys were taken from asylums and homes of different kinds. These “little mites … started with horses at the age of eight or nine years old.” The practice of exploiting youth and poverty was no different North or South; only skin color differed.20

As in the South and in Kentucky, race relations among jockeys and horse trainers existed in a fluid state that lacked hard-and-fast color lines, rules, or even legal practices that would have segregated the races. Black jockeys rode against white in the top-level races in the Northeast during the decades following the war: Murphy’s greatest rival was the white “Snapper” Garrison, who was of Irish descent. Murphy did not live long enough to witness the racial clash that would occur following his death, when white riders would form a cabal hostile to black jockeys. During Murphy’s era, black and white jockeys rode races alongside one another, generally without problems. These fluid relations ended shortly after his death.21

White jockeys did not stand alone in harboring increasingly hostile feelings toward blacks. In his biography of the black jockey Jimmy Winkfield, a native of the Bluegrass whose career succeeded Murphy’s, Joe Drape tells how elite New Yorkers who patronized racing and owned horses expressed repugnance over jockeys of both races—but mostly over blacks. “Immigrants already overran the sport,” Drape writes, “and for that matter, the city, encroaching on what the Jockey Club members had believed was a gentleman’s game. The migration north of Southern blacks, along with the resentment it stirred in the city’s new white arrivals, threatened the Jockey Club’s image of what the sport of kings should look like on this side of the Atlantic.” It was felt that urchins from the streets and orphanages “were preferable to the country darkies who followed idols like Murphy, Hamilton, and Simms east to grab a piece of horse racing’s richest purses.”22

Murphy’s era—from the 1870s through the early 1890s—thus marked the high point for black horsemen in the racing world. The racetrack life held the promise of a way out of poverty for white and black youths; down in Kentucky, African American youths like Murphy had numerous examples of achievement to emulate. Murphy’s own mentors included the renowned horse trainer Eli Jordan, a former slave who later took in Murphy and his widowed mother at his residence in Lexington, presumably after they had left Murphy’s grandfather’s home. The young Murphy also took advice from William Walker, a slightly more experienced jockey who expressed pride for all he taught the aspiring rider. Murphy’s other mentors were white: Mrs. Hunt Reynolds, who appeared to have had a great hand in managing the operations of her husband’s racing stable, and James T. Williams, who developed the careers of a number of young jockeys in Kentucky and owned a racing stable in partnership with a man named Richard Owings. Young Murphy, fourteen years old when he first climbed aboard a Thoroughbred, was fortunate to learn his craft in Kentucky, where large numbers of horsemen lived and always were on the lookout for small black boys to bring into the trade.23

Murphy’s mother, America Burns, was a laundress in Lexington whose customers included the racing stable owner Owings. In 1873, she allowed Owings to take her son, said to be very small for his age, into an apprenticeship to teach the boy how to ride. Murphy, still using the surname of Burns at that time, did not start down his career path in a blaze of instant glory. He fell off the first horse he climbed aboard and was reluctant to try again. Williams drew on his own great finesse to persuade him to get back on the young horse that had thrown him. Murphy succeeded. He remained on the farm through 1874, although at that point he failed to attract much notice for his riding. He had not yet polished his skills.24

Murphy’s life changed dramatically in January 1875 when his mother took him to Jordan, who was working as the horse trainer at the tracks for Williams and Owings. Jordan took the youth to Louisville to the racetrack still under construction—the Louisville Jockey Club Course, to become known later as Churchill Downs. Murphy’s athletic talent blossomed while exercising horses for Jordan on the track. The two developed a father-son relationship that would endure until Jordan’s death in 1884. Murphy called Jordan “the old man” out of fondness. Others, calling him “Uncle Eli,” uncle being a popular way of addressing black men, recognized Jordan as a horse trainer of superior knowledge and skill. Clearly, Jordan had a powerful influence on young Murphy while instilling in him the work ethic and honesty that would take him far in his career. This was not to say that Murphy did not come to Jordan with an extraordinary focus that was unusual for a youth. “Isaac was always in his place and I could put my hand on him any time day or night,” Jordan said. “He was always one of the first up in the morning, ready to do anything he was told to do or to help others. He was ever in good humor and liked to play, but he never neglected his work but worked hard summer and winter. He never got the big head.”25

Murphy was fortunate to work in Jordan’s care at the racetrack for reasons that went beyond the mentoring the older man could provide. By living and working at the racecourse as a young man, he managed to sidestep the violence of the type that John Harper had ordered carried out on two domestic servants at Nantura Farm. Domestic labor was easily replaced; skilled jockeys and trainers were not. The campaign of violence against blacks in Kentucky did not, with rare exceptions, touch those blacks holding down high-profile positions in Thoroughbred racing. Two exceptions were incidents involving the jockeys Billy Walker and Jimmy Winkfield. Walker said that the operator of Churchill Downs, M. Lewis Clark, threatened him with violence if he failed to ride an honest race in the famous matchup of the Kentucky-based Ten Broeck with the California mare Mollie McCarthy in Louisville in 1878. “You will be watched the whole way, and if you do not ride to win, a rope will be put about your neck and you will be hung to that tree yonder and I will help to do it,” Clark informed the jockey. During the early twentieth century, Winkfield claimed that he received threats “from the Ku Klux Klan,” according to his daughter, Mrs. Liliane Casey. But these claims of threats were exceptions within the safe haven of horse racing during decades of violence that made Kentucky a dangerous place for all, but especially for persons of color.26

Crimes against blacks reached such serious proportions that the Freedmen’s Bureau set up an office in Lexington with the intention of protecting the civil rights of newly minted black citizens. The presence of the Freedmen’s Bureau, mandated only for those states that had seceded, spoke volumes about the volatile situation in Kentucky. And events in Kentucky kept the bureau busy. Marion Lucas has cited a bureau report from 1866 detailing 58 incidents against African Americans in Kentucky, “including more than two dozen whippings and beatings of men and women, three rapes, eight attempted murders, nine murders, and one case of burning a freedman alive.” The 1866–1867 report of the Freedman’s Bureau in Kentucky cited 319 cases of mistreatment of African Americans. And so went the reports in succeeding years. “Much of the violence that gripped Kentucky in the years immediately following the Civil War,” Lucas writes, “stemmed from the prevalent belief of whites in the inferiority of blacks….The desire of the majority of white Kentuckians to keep freedmen ‘in their place’ allowed a minority to … [create] a ‘system of terrorism.’”27

The terrorism occurred as much in central Kentucky, where Murphy grew up, as it did throughout the state. Most telling concerning terrorist activities has been George Wright’s research revealing how the lynching trend in Kentucky followed a course counter to that in the rest of the United States. While lynchings did not reach their greatest numbers nationwide until 1890, their numbers had been high in Kentucky from the outset. In other words, racial hate in Kentucky had been aggressive from the end of the war on. The evidence could be found throughout horse country: less than a month before the Harper killings and the subsequent mock lynchings, whites hanged an African American at Frankfort, the state capital. On election night two weeks following the Harper killings, whites took two blacks from the jail in Versailles, the seat of Woodford County, the same county where Nantura Farm was situated, and hung them.28

Angered, and greatly concerned, African Americans in Frankfort and the surrounding regions sent a petition to the U.S. Congress documenting more than one hundred cases of violence from November 1867 to May 1870. These incidents included twenty-four mob lynchings, the killing of twenty-one men and three women in mob violence, and numerous incidents of beatings and whippings. Blacks found little justice. As Lucas writes: “The system of intimidation and terror, the prohibition of black testimony against whites in state courts until 1872, and the hostility of most whites toward federal involvement, made it difficult to arrest, and virtually impossible to convict, those charged with crimes against blacks.” Moreover, not only did those persons of the highest social ranking in the Bluegrass—the landowners who bred racehorses—seem disinclined to come to the aid of blacks under siege; they were part of the violence. The New York Daily Tribune identified Kentucky’s “gentry” class—its horse breeders—as one and the same as the Ku Klux Klan.29

In Frankfort, the state legislature surprised many Kentuckians when it began considering a bill to repeal the lash. This possibility so greatly alarmed the Kentucky Gazette that the editor felt compelled to warn: “Theft and violence will become much more prevalent. While the negroes were slaves they were kept in perfect subjugation by the lash, and it is its disuse that has made them such pests of society.”30

In contrast, people simply did not read about violence inflicted on either black jockeys or black horse trainers in Kentucky. Threats of violence surely occurred, assuming that Walker and Winkfield were not exaggerating. But outright violence, or at least publicized violence, appears not to have taken place within the sport of horse racing—not until the 1890s, when racism grew exponentially in the larger world. After that time, and mirroring events in the larger society, white jockeys ganged up on black jockeys at a number of racetracks. By the end of the decade, and following the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) upholding racial segregation, black horsemen and trainers simply disappeared from their high-profile positions in the sport. But, before that time, the jockey and horse-trainer labor pool existed as integrally important to the smooth function of the sport in Kentucky. Murphy and his fellow black riders, along with black horse trainers, appeared to live their lives free of the fear of racial harassment. They were too important to the economic order of the sport, which could not operate without them.

Murphy’s jockey career had risen like mercury on a hot day. He went from riding at a country course southeast of Lexington, Crab Orchard, to riding at the new track in Louisville in 1875 and at Lexington in 1876. By 1877, he was riding summers at Saratoga, where the former slave jockeys Abe Hawkins and “Sewell” had preceded him during the track’s early years. He achieved great success while riding largely against white jockeys. By the early 1880s, he had moved to the sport’s top echelon and was dictating the terms of his riding contracts to the wealthy men whose horses he rode. The public recognized him for the star athlete that he was, his behavior unimpeachable both on the track and at leisure in the city of New York. Walter Vosburgh, a distinguished racing official and writer on turf matters in New York, described Murphy in 1884 as “an elegant specimen of manhood … strong, muscular, and as graceful as an Apollo.” That same year, the Louisville Courier-Journal commented on Murphy’s renown throughout the United States, observing that the jockey looked “like a Sphinx carved out of ivory … familiar on every racetrack in America.”31

In a fortunate coincidence, Murphy’s best years coincided with the increasing presence of still another set of “new men” who brought big money and their own brand of ostentatious living to the rapidly expanding sport. These were the mining kings of California and other Far Western states, who began sending their stables east. Their Eastern competition consisted in great part of the Lorillard brothers, Pierre and George, who were beginning to win so many races with their vast numbers of horses that owners of the majority of racing stables would come to regard them as crushing the sport in New Jersey and New York. The Lorillards weren’t really crushing all the competition, only most of it. Two more brothers who had recently joined the game would cause the Lorillards frequent anguish by crushing them in turn. These were the Dwyers, Phil and Mike, former butchers who had parlayed their business into wholesale meat distribution in New York. The Dwyers weren’t the least bit interested in “improving the breed,” as the sportsmen of Belmont’s social set claimed to have been. Quite in contrast, the racing stable of Mike and Phil Dwyer existed solely for the purpose of setting up betting opportunities for the two brothers. They excelled at betting even as their stable of horses excelled at winning races because they bought the best horses available. They even built their own racetrack in Brooklyn, competing directly with tracks patronized by Belmont’s social set.32

Murphy rode this expansion of racing with the mastery of an athlete playing all his best options. By the mid-1880s, he was riding for George Lorillard, Elias “Lucky” Baldwin, and the fiery Ed Corrigan from Chicago. Phil Dwyer made some huge errors in judgment by betting against some of the horses Murphy rode when he thought him to be riding the inferior horse. He lost those bets. One example was with the Freeland-Miss Woodford rivalry. In three different races at the Jersey Shore’s Monmouth Park, Murphy rode Ed Corrigan’s Freeland against Phil Dwyer’s Miss Woodford and defeated the mare twice. As the first American racehorse to win more than $100,000, Miss Woodford was not your average mare; consequently, defeating her was no small achievement. Refusing to believe the obvious, Phil Dwyer bet Corrigan $20,000 that Freeland could not defeat Miss Woodford again in a fourth race. The Dwyer brothers put the best jockey of the times on Miss Woodford—an Irishman, Jim McLaughlin—but to no avail. Freeland defeated the mare. The race inspired lines of poetry in the press, as events of that era often did, with this particular piece telling how,

Freeland came with a sudden dart At the finish, and Isaac proved too smart For the Dwyers’ jock; how at last He nailed him just as the post was passed.

Murphy was raising the bar for jockeys, elevating this form of labor to a profession, an art, a niche in athletics that inspired admiration and lines of poetry. The results were paying off handsomely. The jockey was riding “first call” (first option) for the gambler/horse owner Lucky Baldwin, and they both were profiting from the arrangement.33

This is not to say that Murphy was participating in gambling scenarios with Baldwin. He was renowned as much for his honesty as for his riding skills. When mentoring young black jockeys, he advised them to be honest above all else—wise words in a world where jockeys of color would have been well advised to be honest or else risk personal violence. “Stoval, you just ride to win,” he once advised the young African American rider John “Kid” Stoval. “Just be honest, and you’ll have no trouble and plenty of money.” Murphy’s arrangement with Baldwin and other gambler/horse owners consisted only of his riding fees, but the fees he commanded during the height of his career made him rise to a comfortable, upper-middle-class status, financially well-off.34

With his rising income, Murphy surrounded himself with accoutrements appropriate to the lifestyle at this level: a move into a home that his contemporaries described as a “mansion” on Third Street in Lexington, the acquisition of his own horse-drawn carriage, a valet (who, ironically, was a white man), a respectable wife, Lucy, and social standing in Lexington’s upper-class black community. Lexington’s white community afforded him no small measure of respect. One indication of this was the habit of one local newspaper, the Kentucky Leader, of reporting periodically on social occasions held at Murphy’s home. It described these events almost as though they had taken place at a white person’s residence, although it consistently made it clear that this was colored society. Judging by these accounts, when Lucy and Ike Murphy entertained, they spared no expense and invited the highest social strata among Lexington’s black residents.35

One time, the Murphys held a reception for the black riding star Tony Hamilton and his new wife. The Leader reported: “Before 2 o’clock there was a long line of carriages in front of the Murphy mansion, and one hour later the lower rooms were packed with the colored crème de la crème of Lexington.” The reception was on a scale that had “seldom been equaled even in white circles.” The newspaper described the bride, Annie Messley, as a woman “very light in complexion and quite pretty.” Degree of blackness mattered and was equated by both blacks and whites with class stratification. The newspaper also carefully noted the social standing of Murphy’s guests: “Isaac Murphy, Tony Hamilton and Isaac Lewis have each won deserved turf honors, and are all upright, honest men, and are well to do people.” Other guests included such local African American professionals as Dr. Mary Britton, an educator who later became a physician and ranked as one of Lexington’s most respected citizens. On another occasion, this one marking the tenth wedding anniversary of the Murphys, the Leader was on the social scene once more, reporting on the event, and including the menu in the report: quails with champignons and claret, oyster patties, turkey with chestnut dressing, croquettes with French peas, and other epicurean delights. Murphy and his guests dined well.36

A rich diversity existed in Lexington’s African American community, with Murphy and his wife clearly representing an upper middle class. Ike and Lucy’s widening circle of acquaintances would have brought them into contact with an impressive group of black professionals: besides Dr. Britton, this would have included other physicians, pharmacists, elected politicians, lawyers, journalists, landowners, clergymen, building contractors, and architects. The black community was conscious of class stratification just as the white community was in its own sphere; Ike and Lucy Murphy moved to their mansion on Third Street presumably to escape their older neighborhood of Megowan Street, which was fast becoming Lexington’s red-light district. It is interesting that the Murphys did not sell their house and property on Megowan Street. They became landlords, renting the house to a black man.

Isaac Murphy’s mansion has been erroneously identified by some historians as this house, the Richard T. Anderson house on Third Street. Murphy’s mansion was of the same size and of similar design and located within two blocks of the Anderson house. No photograph of the Murphy mansion is known to exist. Like this house, Murphy’s mansion contained ten rooms and had an observatory on the roof where Murphy could watch horses training or racing nearby at the Kentucky Association track. (Courtesy of Transylvania University, J. Winston Coleman Kentuckiana Collection.)

The move the Murphys made to the large house on Third Street suggested that they were intent on elevating their social position to a level much above the laboring class since Murphy had acquired nationwide recognition as a star athlete. This was a further indication that he was elevating the jockey profession above that of its former niche in the laboring class. Despite his rise to fame, however, Murphy might have realized that the jockey profession continued to suggest connotations connecting it with a class of labor. He revealed his awareness of this when he once said: “I am as proud of my calling as I am of my record, and I believe my life will be recorded as a success, though the reputation I enjoyed was earned in the stable and saddle.”37

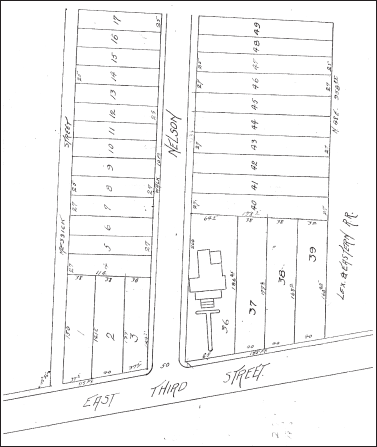

This is a plat drawing of the Isaac Murphy mansion, the only known image of the house that was situated on the roughly seven-acre plot that Murphy owned on East Third Street. The lots shown in this drawing were created after the jockey’s death in 1896 and on subdivision of the property in 1903. The developer proposed that a street be run through the property, to be known as Nelson Avenue. An advertisement (“Big Sale of Lots Tuesday, April 14,” Lexington Herald, April 14, 1903, 10) for the sale of these lots described the residence as two-story brick with bath, water, and lights. It noted that the property was situated close by the Lexington and Eastern Railroad tracks. (Netherland Subdivision, Plat Cabinet E, Slide 96, Fayette County Land Records, County Clerk’s Office, Lexington.)

Compare the Murphy house (facing page) with this drawing for the Anderson house, a nearby mansion that has been mistakenly identified as Murphy’s house. The Anderson house was situated farther east on Third Street, across the railroad tracks and near Clay Avenue. A newspaper advertisement (“Public Sale of the Most Elegant Residence in Central Kentucky,” Lexington Leader, July 7, 1888, 4) announced a public sale of the Anderson house. Many years later, the house became known as the Railroad YMCA. (Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, 1907, University of Kentucky Special Collections, Lexington.)

His talent in the saddle appeared to erase the color line for Murphy during these fluid times when white society remained undecided over “what to do with the Negro in American society,” as Myrdal put it. The times were, indeed, in flux: lynching was on the rise nationwide as the close of the nineteenth century approached; racial segregation was on the horizon even as the lives of African Americans evolved along a track similar to those of whites in matters of status and class separation. At times, these parallel tracks crossed, as Murphy’s did in the sport of horse racing. But not all blacks prominent in the sport of racing received recognition equating them with whites even if they did receive respect. Respect, like everything else, was stratified.

An example involved the house servant named Peter, long employed as the major domo of McGrathiana, the horse farm of Hal Price McGrath, the winner of the inaugural Kentucky Derby in 1875. Whites who were outsiders to the Bluegrass did not recognize Peter as their equal, yet they afforded him wide respect. Peter’s reputation as an efficient, loyal house servant extended far beyond the Bluegrass and resulted in a biographical sketch written in 1874 in Turf, Field and Farm. Peter amused the house guests at McGrathiana, for he appeared to exercise a great amount of power. All knew that any power he appeared to possess came only at the discretion of McGrath; yet, when Peter ruled the hallway and dining room at McGrathiana, no one would have suggested this imbalance in power anywhere within his hearing. While Murphy epitomized the independent, high-achieving black man from Kentucky, Peter represented an entirely different sort of Kentuckian: the well-loved family servant, the holdover from slavery days who also, perhaps because of family loyalty, appeared to be protected from lynching and other forms of violence. The writer for Turf, Field and Farm got it right when he wrote of Peter: “He is one of those servants so highly prized by the rich and cultivated planter in ante-bellum times.” He was, indeed, a picture of antebellum times, a throwback to an era that, ironically, was to become the future for Kentucky’s troubled horse industry by the twentieth century.38

Picture Peter presiding over a battalion of waiters in the dining room, issuing orders “with Napoleonic decision,” as Turf, Field and Farm described him at work. “When on duty Peter permits no subaltern to trifle with his dignity…. He bears himself like an aristocrat, and by the set of his hat and the cut of his coat you are impressed with the fact that he is a colored individual of no ordinary pretentions. In the eyes of Peter there is no place like Kentucky…. He will whisk out his broom five hundred times a day, and if no objections are made, will brush such a man’s coat threadbare, and carelessly ram into his vest pocket every fifty-cent stamp or dollar bill that you thrust into his hand…. Peter is a type of the polite, dignified old family servant of the chivalric days before the war. He does not care a snap of his finger for Mr. Sumner’s pet measure, the Civil Rights bill, for he has enjoyed more privileges by voluntary concession than could have been conferred upon him by the working of a law which appeals to or stirs up the prejudices of race.”39

The winning team for the first Kentucky Derby in 1875 was the horse Aristides; his owner, Hal Price McGrath; and the jockey Oliver Lewis. (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

When McGrath would take his racing stable to the June race meet at Jerome Park, he would take Peter along as well. This pair of “worldly men”—the Kentucky gambler-horseman and his loyal servant, who had a penchant for betting on horses and for making conversation with the ladies—must have presented quite a contrast to other Kentuckians like the sphinx-like Murphy or even the wild and frontiersman-looking John Harper. Peter would be “in high feather” when McGrath took him northeast to the races. The black man was always on the lookout for a financial backer, persuading any likely prospect “with many bows and scrapes” to bet money for him on a horse of which Peter whispered he had inside knowledge because he worked for McGrath. Judging by the story in Turf, Field and Farm, Northeastern racing patrons regarded this act with paternal affection. They acquired some of their impressions of Kentuckians from this duo of Bluegrass representatives. Interestingly, the impressions gave no indication of the violence raging in Kentucky.40

While Northeastern whites patronized Peter’s bowing and scraping for betting money at the racecourse, they appeared to think nothing odd about Murphy, higher up the social scale, dining next to them at the major social event of the summer of 1890 at Monmouth Park, a celebration given by the horse trainer Matt Byrnes at his home near Eatontown, New Jersey, in honor of the great horse that Murphy rode named Salvator. On this occasion more than any other, the respect that whites professed for Murphy intersected so neatly with the rider’s achievements and fame that differences of skin color seemed wiped away from the slate of cultural and racial beliefs.

James Ben Ali Haggin’s stable owned Salvator, whose rivalry with a horse named Tenny grabbed the attention of racing fans, as had previous rivalries between Kentucky and Asteroid, Longfellow and Harry Bassett, and, later, Ten Broeck, Tom Ochiltree, and Parole. Salvator and a filly named Firenze were arguably the two best horses to emerge from Haggin’s vast equine empire, which comprised his forty-four-thousandacre Rancho del Paso in California and, later, upward of eleven thousand acres at Elmendorf Farm, which he would establish in Lexington. Murphy rode both these racing stars from Haggin’s stable. He was at the height of his career.41

Haggin actually was returning to his roots when he purchased the initial portion of Elmendorf in 1897, for he was born in Harrodsburg, Kentucky, in 1821. He had practiced law in Kentucky, Mississippi, and New Orleans before following the gold miners to California during the rush of 1849. He had not gone to California searching for gold, instead opening a law office with Lloyd Tevis in Sacramento. He did find gold, however, in the form of a silver mine in Utah in which he, Tevis, and George Hearst invested. They also invested with Marcus Daly in the Anaconda copper mines in Montana, the Homestake mines in South Dakota, and other operations, including one in Peru. Haggin had begun buying Bluegrass horses from Tennessee and Kentucky in the 1880s and won the Kentucky Derby with Ben Ali, purchased in Kentucky. He was also winning races that impressed the Northeastern establishment, races like the Belmont Stakes and the Withers Stakes. He came out on the side of those breeders who stood by the bloodlines of the great stallion, Lexington, since the dam of Salvator, Salina, was one of the best daughters of the old horse.42

Murphy might have heard the story of the naming of Salvator, how the colt whose sire was an English import named Prince Charlie had originally received the name Effendi. Writing The Great Ones, Kent Hollingsworth told how Haggin’s valet, an African American, was shining his employer’s shoes one day when Haggin noticed that the man’s bald head was the same color as Effendi’s coat. That might have been the reason, according to Hollingsworth, why Haggin renamed Effendi as Salvator, after the valet. By any name, Salvator was a top-level racehorse, winning stakes races at ages two and three. At age four in 1890, he and his rival, Tenny, gave Murphy, Haggin, and all racing fans memories of the type that sometimes come only once in a lifetime.43

The excitement over these two horses began building after Salvator won the Suburban in New York, defeating Tenny, among others. Murphy sat enthroned in a floral horseshoe after winning the Suburban, a custom for jockeys on winning some of the most significant horse races of that era. His adoring fans would not permit him to climb down from the floral shoe on his own but carried the arrangement, with him still enthroned, to a place where he and other jockeys gave interviews to the newspaper reporters. All the while, Tenny’s owner was chafing. He believed that his horse should have won the race and so challenged Haggin to a rematch. The showdown was set for the Coney Island track late in June. When Salvator and Murphy stepped out on the track, the pair looked like “the idealization of horse and jockey,” read a report of the race. “The crowd seemed to recognize the fact, and round after round of applause came from the masses of people in the stand, on the lawn, and, in fact, every place where a sight of the race could be obtained.”44

One of the most celebrated sports events of the latter nineteenth century was Salvator’s defeat of Tenny at Sheepshead Bay in New York, June 25, 1890. Isaac Murphy rode Salvator to victory by the length of half a horse’s head. A white jockey, “Snapper” Garrison, rode Tenny. The race inspired Ella Wheeler Wilcox to write the poem “How Salvator Won.” (Courtesy of the Keeneland Association.)

Sports aficionados credited Murphy and his unflappable calm on horseback with holding off Tenny’s challenge in the late homestretch to win by the length of a horse’s head. The contemporary poet Ella Wheeler Wilcox immortalized the race in a poem published in the Spirit of the Times, a section of which reads:

One more mighty plunge, and with knee, limb and hand I lift my horse first by a nose past the stand. We are under the string now—the great race is done— And Salvator, Salvator, Salvator won!45

Murphy was clearly the hero on this June day in 1890, receiving the crowd’s applause with the stoic visage he always showed before the grandstands. The Salvator-Tenny rivalry moved to New Jersey in July to the newly rebuilt Monmouth Park, which the New York sportsman David Withers had reconstructed on a scale previously unknown in sports. Salvator won his race at Monmouth by four lengths. The Spirit of the Times declared: “About the immense superiority Isaac Murphy shows over the majority of the jockeys at the present day … there can be no room for doubt.” Two weeks following that race, Byrnes staged the famous party to celebrate Salvator’s victories. Murphy sat down at the table among the white guests, among whom were “half the judicial and political ‘somebodies’ of New York.” According to photographic records, Murphy appeared to take his place among whites with ease. He was elegantly attired in a velvet-collared coat and derby. The clambake in honor of a horse and jockey who had made a success of the season was itself a huge success. The champagne flowed heavily that day.46

Two days later, the bottom fell out from under Murphy’s career. He reappeared on the track to ride Haggin’s fast filly Firenze at Monmouth Park—and lost the race, finishing seventh. It seemed that the entire world noticed he had trouble riding the filly. The New York Sun, in a report reprinted in the Kentucky Leader, told how Murphy “was listing to the left and clinging to the saddle” during the race. Perhaps one hundred yards beyond the finish line, the filly slowed to a trot on her own, and Murphy rolled out of the saddle and was “picked up by bystanders, while others hurried forward and caught the mare.” The bystanders helped him back into the saddle so that he could return Firenze to the unsaddling area. Then he forgot to ask the permission of the judges to dismount, in accordance with racing rules. His friends had to put him back on Firenze once more in order to follow through with this requirement. After weighing in on the scales, Murphy had to be almost carried to the jockeys’ locker room. Rumors ran wild throughout the racetrack grandstand that he was drunk. His friends “hurried him into his clothes, secured a carriage, and drove him home.”47

The aftermath for Murphy was suspension from the track and an immense scolding in the newspapers, for it appeared that he might have ridden while drunk. The New York Times exclaimed that it was “past belief” that Murphy would make such an embarrassment of himself. The Times pointed to the clambake two days previously as perhaps the start of a drinking binge. The New York Sun certainly was convinced that Murphy had been drunk, for its reporter had “heard” that the jockey was not a novice to a state of inebriation. The honest man’s jockey, Murphy, denied these accusations. He told how prior to riding Firenze he had visited with his wife, Lucy, in the grandstand, where they asked the waiter to bring them a glass of mineral water. Murphy’s white valet, the waiter, and the cashier at the grandstand all insisted that Murphy drank nothing but the mineral water during this short visit. Witnesses next to the jockey scales reported that they saw nothing amiss with the rider when he weighed out to ride the race. Matt Byrnes, who was Firenze’s trainer and Murphy’s host from the clambake, said he saw nothing wrong with Murphy when he met him in the paddock prior to the race.48

No one ever learned what really had happened to Murphy that day. Well known was the fact that, like many jockeys, Murphy went to extreme measures to keep his weight low so that he could ride races. Jockeys of that era believed that drinking champagne would renew their energy and, thus, offset the debilitating side effects of the dramatic weight-loss programs they endured. Murphy followed this practice and began taking “intoxicant drinks” in the years prior to his death “to aid his strength against the exertions of [weight] ‘reducing’ necessary to this profession,” according to his friend and attorney L. P. Tarlton. Vosburgh, the respected turf correspondent in New York, revealed that Murphy had reduced from his “winter weight” of 140 pounds to 110 pounds in order to ride Salvator during the 1890 season.49

The possibility exists that something else happened to Murphy. The New York Sun reported: “There was a rumor, and a very strong one at that, that the jockey had been drugged by somebody who had bet heavily on other horses in the race.” Murphy returned to his mansion in Lexington, where, according to the Louisville Commercial, he was “confined to his house by sickness”: “Murphy has never recovered since his sickness at Monmouth…. He was undoubtedly sick at the time, and not drunk, as at first reported.” The Louisville newspaper revealed that it had received “private information … that Murphy, on his physician’s statement, is suffering from effects of poison probably administered to him that day at Monmouth Park…. The physicians [sic] declares that Murphy will never fully recover from the poisoning.” When the Kentucky Leader interviewed Murphy, he said he could not say for sure whether he had been poisoned. “But,” he continued, “something suddenly got the matter with me and I have never been well since.” Whatever had happened, Murphy’s career wound down rapidly from that point, with many believing that he became an alcoholic in his later years.50

Murphy won the third of his trio of Kentucky derbies the following spring. But his nationwide popularity had suffered immensely from the Firenze defeat and the suspicions that surrounded the incident. Despite a long and respected career, he passed within a mere few weeks from a jockey carried about on the shoulders of whites in a winner’s floral horse shoe to a rider suspended by racing authorities at a Northeastern track and harshly criticized in the Northern press. With the Murphy controversy, it appeared that the public and all the racing sport were beginning to be less forgiving of black jockey stars.

In fact, news reports were beginning to appear about white jockeys forming hostile cabals against black riders. In 1900, the New York Times published its previously mentioned article about white riders forcing black jockeys off the turf. “[The] negro jockey is down and out,” read the report, as a result of the work of “a quietly formed combination to shut him out. This edict is said to have gone out at the first race meeting of the year … that horse owners who expected to win races would find it to their advantage to put up the white riders…. Gossip around the racing headquarters said that the white riders had organized to draw the color line.” A race war was looming at the nation’s racetracks, and the white jockeys did not consistently lead the charge. At the Latonia Race Course, a white jockey complained in 1891 that black riders were conspiring to injure him during the races he rode. The Spirit of the Times considered this complaint while observing an irregular amount of accidents during the races at that track and concluded: “Whether or not there is something like race feeling and prejudice in the ranks of the riders, it is certain there has been altogether too much jostling and crowding.”51

News reports like these might not have shocked anyone of that era, considering how sports were mirroring daily life. Racism was on a parallel course in the larger world: the number of lynchings was increasing throughout the United States and would reach its highest point during the 1890s. In a few short years, the sport of Thoroughbred racing no longer would provide the safe haven for the black stars of the turf that it had for some twenty-five years. Racing would follow in the footsteps of the larger world.52

Like old John Harper before him, however, Murphy had reaffirmed to Northeastern horsemen that the Bluegrass was home to some of the foremost horsemen, as well as to fast horses like Lexington, Asteroid, Longfellow, and an ever-expanding number of turf stars. Horsemen like Murphy helped make it easy for outsiders to equate the Bluegrass region with the racehorse. Sadly for those African Americans who trained racehorses and rode them as jockeys, these contributions at the sport’s highest levels would soon be ignored and then forgotten as the sport’s front lines, most visible to horse owners and the public, became completely white.

Blacks remained heavily involved in racing, but their duties were confined to the stables, where they were not quite so visible to the public. With American society becoming segregated, and with blacks relegated to invisibility in all aspects of life, it would hardly have seemed right for black jockeys to continue receiving the public accolades that Murphy and other black horsemen had received so freely during a time of more fluid race relations. But that time had occurred before whites finally figured out, as Myrdal would put it, “what to do with the Negro in American society.”