John Madden’s rise to national prominence occurred during a time when plantation literature experienced renewed popularity. This genre of fiction had existed at least since the 1830s but was sweeping the country once more beginning in the 1880s and into the twentieth century. Writers of plantation fiction extolled an antebellum South that was to a great extent imaginary. The picture that emerged was a vision of gentle twilight washing across the wide verandas of old mansions where sweet magnolias bloomed in perpetuity. Servants hovered discreetly in the shadows of stone columns on these moss-covered porticos, poised to fill the white folks’ glasses. Life seemed so orderly and romantic for these cavaliers and Southern ladies. Perhaps, in this picture, a well-bred horse stood nearby. Or at least, in the imagination, you could hear a Thoroughbred neighing in the distance.1

A great many Americans of the early twentieth century actually had convinced themselves that life might be better lived in terms of this fanciful past portrayed as the Old South. The North had spent decades resenting the Southern states for their folly in bringing on the Civil War. But, by the end of the nineteenth century, it had changed its mind. Northerners were becoming increasingly enamored of the old slaveholding South. The plantation genre of popular writing transported them into this lost and fanciful past.

Certainly, no one could forget that the war had been the bloodiest one ever fought on American soil. Considering that some 2.5 million men fought on the Union side and another 750,000–1.25 million on the Confederate side, a generation of children had come of age in families that likely included at least one ex-soldier. And, since 600,000–700,000 men either were killed during the fighting or died of war-related injuries or illnesses, many of these families would have suffered the loss of a relative. Despite these former divisions among Americans, the populations of North and South were beginning to express forgiveness as the old soldiers began dying off and a new generation matured. Among those soldiers still living, Union veterans marched alongside former Confederate enemies at reunions.2

These early-twentieth-century Americans took up a practice that William Taylor had seen in the regional beliefs prevalent in the North and the South before the war. He concluded that these beliefs had the power to make myths and that the literature of the antebellum era reflected these myths. He saw Northerners as highly dissatisfied with their rapidly changing world and, consequently, looking for an escape. He wrote: “Northerners soon found much to criticize in the grasping, soulless world of business and the kind of man—the style of life—which this world seemed to be generating.” According to Taylor’s theory, imagined days from an orderly, more pleasant past offered an escape from rapidly changing times.3

Much the same process appeared to be transpiring in the literature popular during the early twentieth century, as David Blight has argued. The popularity of plantation literature lay in the escape it offered its readers into a more pleasant past depicted in the lifestyle of the antebellum South. Blight notes that the 1890s and the early years of the twentieth century saw small family businesses fail and the gap widen between the superwealthy and the rest of Americans. Immigrants began arriving in great waves, unsettling native-born Americans, who perceived this influx of foreigners as threatening to the American way of life. “The age of machines, rapid urbanization, and labor unrest produced a huge audience for a literature of escape into a pre–Civil War, exotic South,” Blight writes. He finds it significant that Northerners embraced this notion of an idealized South when, for decades, the South, in the general estimation of the Northern population, had existed in a benighted condition.4

Simultaneously with this popular literary wave, Bluegrass Kentucky began to swap the remnants of its Western identity for stereotypes identifying it with the South. Kentucky’s history as a former slaveholding state enabled this transition that took place within the national imagination. Plantation literature made it easy for Americans to associate all former slave states with the Confederate South. No longer did Americans need to grasp the political and social nuances that had distinguished the border state of Kentucky from the South. Bluegrass Kentucky became the South, its geographic proximity to the South assisting this transition. Travelers from the North found the Bluegrass more accessible than the Deep South. They imagined that they caught glimpses of the Old South in Bluegrass architecture and lifestyle. Bluegrass Kentucky, with its slaveholding history, its large homes, and its pastures filled with horses, evolved as the Near South and, thus, as representative of the Old South.

Americans embraced this popular plantation literature at the same time as they began to accept the growing popularity of the Lost Cause, the name given to an idealized form of Civil War memory. A groundswell of this reconstructed memory began sweeping the United States during the 1890s and continued strong into the early twentieth century. The myth that it created united people from all regions, North and South, in embracing the notion that perhaps the Old South had got it right after all—that perhaps the Civil War really had been fought to defend a lifestyle of high ideals and to preserve the Constitution, rather than in defense of slavery. Southerners had been reciting Lost Cause ideology from the time they had lost the war, attempting to explain the war to the North in these terms. This clever notion allowed the South to save face in its failed attempt at secession. Northerners had never bought into this idea—at least not until late in the nineteenth century, when racism had reached a high pitch, immigrants were arriving in increasing numbers, life seemed out of control, and white Americans feared that their way of life was endangered. As an antidote, they looked back fondly to an imagined past. They found this past in the Lost Cause. And they found it in plantation fiction.

William Ward has characterized such writing as being in the “Genteel Tradition.” Like Taylor and Blight, he has told how this popular literary genre obscured the harshness of daily life. Of its readers he writes: “It was not that they were ignorant of murder, violence, rape, arson, embezzlement, and perversion. They preferred drawing rooms and garden houses to mining and mill towns. When they read, they preferred men and women in their aspiring moments to characters weighed down by trouble and futility.”5

Within this framework, Bluegrass Kentucky experienced a rebirth as the Old South of literature and imagination. Moreover, plantation literature painted the region as something entirely different from the violent Kentucky that most Americans had read about in newspapers. A much more pleasing image of horse country emerged. “The Kentuckians are undoubtedly the finest people in the States…. In some respects they are the finest white people in the world. They carry about them an atmosphere of manners and breeding,” wrote the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder, following in the pattern that plantation literature had set. This reconstructed picture of the Bluegrass began to work a change of mind with those turf moguls who had formerly believed it too unstable for capital investment. As a result, the horse business tagged along for what turned out to be a highly productive ride.6

Kentucky authors who linked the Bluegrass with this imagined Old South achieved wide national acclaim. Foremost among these were James Lane Allen, Annie Fellows Johnston, and John Fox Jr. So many people read these three that the Southern identity they bestowed on Kentucky clearly resonated with a readership eager to embrace the Old South.

This imaginative leap linking Bluegrass Kentucky to the Old South tied up numerous loose ends for those both within the state and outside its borders, for confusion about the entire state’s identity had existed since long before the Civil War. Kentucky never had been entirely of the South—or entirely of the North. It had been a slaveholding state that identified with the South in some situations but not all. For example, and in contrast to the Deep South, Kentucky was a border state generally characterized by farms typically smaller than the vast cotton and sugar plantations of the deeper South. It fell somewhere between the geographic, ideological, and economic characteristics that had differentiated North from South. Bluegrass Kentucky, situated in the central portion of the state, had been caught between both worlds—until Allen, Johnston, and Fox placed it directly within the context of the Old South for their turn-of-the-century readers.

These writers peopled those of their works about the Bluegrass with kindly Confederate-supporting colonels, loyal slaves, and massive, columned mansions that bespoke a social power and grace originating in a timeless connection to the land. None of them cast the typical Bluegrass landowner in the likeness of old John Harper, whose eccentric, wild appearance had more clearly suggested a rough-and-ready frontier type. Authors working in this genre reified an exotic country of the imagination, a sweet country where all knew their proper place.

Johnston wrote a series of children’s books, beginning in 1895 with The Little Colonel; the series made her a best-selling author by the turn of the century. Johnston was not a native Kentuckian but had grown up in nearby Indiana and moved to Peewee Valley, near Louisville, as an adult. The Little Colonel grew into a series of twelve additional volumes that sold more than 1 million copies during Johnston’s lifetime.7

The Little Colonel series, set in post–Civil War Kentucky, featured a “little colonel” who was a young girl five years old named Lloyd Sherman whose grandfather, one Colonel Lloyd, sported a beard shaped in the Kentucky colonel’s stereotypical goatee. He had disowned a daughter who had married a Yankee. The depiction of Kentucky in this series helped reinforce in the national imagination the notion that Kentucky existed as a holdover from older times, a gentle place where violence did not intrude. Anne Elizabeth Marshall has written: “The white characters, around whom Johnston’s stories revolve, present an … appealing picture of graceful gentility as they lead lives of wealth and privilege.” She also writes: “They enjoy a gentle existence buffered from insecurities by a stable social arrangement that entails powerful yet chivalrous men, and well-behaved maternal women. Most importantly, however, this safe, unburdened order rests upon the deference and servitude of faithful, contented African Americans.”8

Allen’s writings portrayed Kentucky in similar organic, orderly, and picturesque terms. Allen was a native Kentuckian, a graduate of Transylvania University who had moved to New York City. He took with him nostalgic and fanciful visions of his home state, an idealized picture that ignored the reality of a violent, lawless Bluegrass straddling the border between North and South. He wrote about a region enveloped in the smooth shadow of the gentle moon at midnight and kissed by the soft breeze of a gentle wind on the green leaves of magnificent shade trees covering plantation-like homesteads. His readers would have interpreted this as Southern.

In Two Kentucky Gentlemen of the Old School, Allen described a social order “which had bloomed in rank perfection over the bluegrass plains of Kentucky during the final decades of the old regime.” He told how the inhabitants “had spent the most nearly idyllic life, on account of the beauty of the climate, the richness of the land, the spacious comfort of their homes, the efficiency of their negroes, the characteristic contentedness of their dispositions. In reality they were not farmers, but rural, idle gentlemen of easy fortunes whose slaves did their farming for them.” The story concerned an antebellum planter, Colonel Romulus Fields, and his faithful former slave, Peter Cotton, who remained with his old master after the war. Together, they expressed displeasure with their present circumstances and worried about the future. Peter Cotton expressed a longing to return to the security of the old ways—slavery. He seemed lost in his new freedom, just as Colonel Fields appeared unable to adapt to the new order of the world. Their familiar world had belonged to a timeless past that they both found more agreeable.9

Not all Allen’s works were fiction, at least not in the truest sense. For Century magazine, he wrote an article titled “Homesteads of the Blue-Grass” in which he anticipated the coming to the Bluegrass of numbers of wealthy men from outside the state. In the 1892 article he predicted: “One can foresee the yet distant time when this will become the region of splendid homes and estates that will nourish a taste for outdoor sports and offer an escape from the too-wearying cities…. A powerful and ever-growing interest is that of the horse, racer or trotter. He brings into the State his amazing capital, his types of men. Year after year he buys farms, and lays out tracks, and builds stables, and edits journals, and turns agriculture into grazing.”10

Allen promised the industrialist that he would discover in the Bluegrass a pleasant escape or at least a respite from the cares of bigcity life, with “no huge mills and gleaming forges, no din of factories and throb of mines.” He described the Kentucky lifestyle as life lived according to gentry-class traditions transplanted from antebellum Virginia, where “in no other material aspect did they embody the history of descent so sturdily as in the building of homes,” and where could be found “the English love of lawns … the English fondness for a mansion half hidden with evergreens and creepers and shrubbery, to be approached by a leafy avenue, a secluded gateway, and a graveled drive.” “On and on, and on you go,” he continued, “seeing only the repetition of field and meadow, wood and lawn, a winding stream … a stone wall … a race-track … and … houses that crown very simply and naturally the entire picture of material prosperity … [with] a front portico with Doric, Ionic, or Corinthian columns; for your typical Kentuckian likes to go into his house through a classic entrance.” Of this typical Kentuckian, he wrote: “After supper on summer evenings, nothing fills him with serener comfort than to tilt his chair back against a classic support, as he smokes a pipe and argues on the immortality of a pedigree.”11

John Fox Jr. was better known for fictional works set in the mountains of eastern Kentucky. In fact, according to Ward, he was the first author “of any consequence to write seriously and sympathetically of the Kentucky mountaineers in their natural habitat, though he himself was born in Bourbon County in the heart of the Bluegrass country.” Allen’s work on the genteel Bluegrass actually had inspired Fox to tackle the intriguing stereotypes of the “two Kentuckys”—the backwardness of the mountain people and their environment contrasted with the perceived gentility and Southern mannerisms of the Bluegrass region. In his most famous work to address these conflicting images, The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come, he wove a story that showed the Bluegrass ways prevailing over those of the mountains.12

The effect of these writers and their literary genre on the horse industry should not be underestimated. It extended into other literary realms, for the metamorphosis of Bluegrass identity to Southern also could be seen in the sporting periodicals of the day. Kentucky horsemen traveling to Northeastern tracks no longer were considered to be of the West, as the Spirit of the Times and Turf, Field and Farm had identified them for nearly thirty years after the Civil War. When Woodford Clay, the owner of Runnymede Farm in Bourbon County, went to New York in 1903, the Morning Telegraph determined that he had “cavalier written all over him.” It described him as “a clean-cut, upright, athletic looking young fellow [recall Madden’s obsessive athleticism here]” and wrote that he “would seem to you to be the beau ideal of the young Southerner of good birth.” It was clear that New Yorkers had been reading all the right periodicals and books.13

As central Kentucky began shedding its Western identity for stereotypes marking the region as Southern, the Bluegrass horse business began to strike gold. Two changes opened wide the veins of this gold mine for the horse industry. First, the state’s notorious reputation for lawlessness shifted away from the Bluegrass to eastern Kentucky. Second, capitalists from outside the state began investing in greater numbers in rural property surrounding Lexington. As the marketing literature of the era revealed, no less than the wealthy moguls of the Northeastern turf were beginning to buy into the notion that the Near South of the Bluegrass region would provide them with an escape from the harshness of their urban world.

Thoroughbred racehorse owners across the United States, always looking for that competitive edge, became fixed on the notion that in Bluegrass farmland lay a dual reward. Their horses would benefit from the mineral-rich Poa pratensis and limestone-infused springwater. The owners themselves would benefit from experiencing the lifestyle of a Southern country squire. Readers of popular fiction could only read about this imagined Southern lifestyle, but the very rich could afford to buy it. Bluegrass farm property no longer seemed an unsuitable investment in an unstable land. The prospect for expansion in Kentucky’s horse industry lay tantalizingly close, more than three decades after Alexander and the Bruce brothers had envisioned this growth. The Kentucky Farmer and Breeder observed: “Breeders throughout America are coming every day to a truer realization of the fact that here and here alone can the best thoroughbreds be raised.”14

The Bruce brothers did not live long enough to see this change. Benjamin Bruce had died in 1891. Sanders Bruce died in 1902. Sanders, in particular, had died a disappointed man. He had enjoyed prosperity during the 1880s and early 1890s, despite a fire early in the 1880s that destroyed the contents of the New York offices of Turf, Field and Farm. The fire nearly forced him to stop completion of volume 5 of the American Stud Book. His problems escalated with the Panic of 1893. He struggled to keep the American Stud Book and Turf, Field and Farm alive. However, he became embroiled in a quarrel with the newly formed Jockey Club over rights to the stud book. The quarrel turned into a lawsuit that nearly ruined him financially. A lower court found in his favor. The powerful Jockey Club appealed. Public sentiment in the world of Thoroughbred racing favored Bruce as the David going up against the Goliath of New York’s turf moguls. The parties settled out of court, with the Jockey Club purchasing all rights to the American Stud Book for $35,000. Thereafter, the name of the Jockey Club replaced that of Sanders Bruce beneath the title.15

The acquisition of the American Stud Book placed the Jockey Club in a tremendously powerful position, with all this power situated in the Northeast. With control of the stud book, the Jockey Club held the keys to the kingdom of the turf since no breeder would be able to register a Thoroughbred in North America without its approval. This gave the Jockey Club the power to bar the horses of anyone it deemed in violation of rules—or held in disfavor. It could do this because no horse was recognized as Thoroughbred, and, therefore, eligible to race, unless the Jockey Club had accepted it into its official registry.

Prior to this consolidation, Kentucky horsemen at least had the option of selecting from two registries. They could choose either Bruce’s American Stud Book or the Jockey Club’s registry. Most people soon realized, however, that they would need to pay double fees and register with both if their horses were to race in Kentucky and New York. The New York tracks required Jockey Club registration exclusively. Racetracks outside New York generally belonged to the rival American Turf Congress, which recognized Bruce’s American Stud Book as well as the Jockey Club registry. But, as everyone had known since Asteroid’s era, a reputation earned outside New York wasn’t all that it could be unless the horse had also raced in the metropolis.

Resentment over the Jockey Club’s control of the New York tracks was no minor matter, as some of the racing periodicals had suggested. “Even the members of the Jockey Club cannot be allowed to claim the whole earth for the purpose of rendering its racing clubs tributary to their demands,” the Canadian Sportsman editorialized during the years when Bruce’s American Stud Book coexisted with the Jockey Club registry. “Certainly … it looks as if they demand the right to step in and dictate to the editor and proprietor of the American Stud Book, not only how he shall run his business, but insist upon it being done just as their lordly will dictates! It may be that the swell Eastern turf magnates believe in their divine right to rule everything from Maine to California.” And perhaps they did. Bruce reprinted this editorial in Turf, Field and Farm.16

For years after Bruce settled his lawsuit with the Jockey Club, tension continued to exist between Kentucky and the New York power structure over equine pedigrees. In 1902, an article in the Lexington Leader pleaded with the Jockey Club to open a branch office in the Bluegrass for the registration of horses. Kentuckians complained in 1906 over the matter of “a disposition on the part of certain Eastern turf journals to criticize the methods of our Kentucky breeders in keeping their records as inaccurate and careless.” Within this complaint lay an underlying concern that leaders of the turf in New York held the power to reject pedigrees and foal registrations submitted from Kentucky breeders. Kentuckians considered this a real possibility, for, when the great stallion Lexington had stood at the zenith of his career, accusations had arisen that he was not, in fact, of the bloodlines said to be his parentage. The power to control Thoroughbred bloodlines definitely had shifted to New York. In light of the way control of the sport had gone, Robert Aitcheson Alexander’s dismissal of “some New Yorkers” when referring to Travers and his group in 1865 seemed like an error in estimation that would haunt Bluegrass Kentucky forever.17

Kentucky was beginning to garner an increasing measure of power in the sport, despite the ongoing controversy over the maintenance of bloodlines records. Some seventy miles west of Lexington in Louisville, a change in ownership of Churchill Downs portended a higher profile for this regional racecourse. An impresario named Matt Winn took over the struggling track the year that Sanders Bruce died. Winn began promoting the Kentucky Derby as something more than a regional race, an event greater than the race of the West, as New York papers called it. He said that he had watched the inaugural derby in 1875 as a thirteen-year-old seated in his father’s wagon parked in the infield. Although he might not have seen the possibilities at the time, his vision for the derby was to work in synergy with the outside capitalists’ expanding investment in the Bluegrass.18

Increasing numbers of Americans did, in fact, begin paying attention to the Kentucky Derby, as a result of a fortunate set of circumstances surrounding the race. In 1913, a long-shot winner named Donerail broke the track record and paid an eye-catching $184.90 on a $2 bet. The resulting newspaper headlines grabbed everyone’s attention. The following year, the derby received considerably more headlines when Old Rosebud shattered Donerail’s recent track record, winning the race in two minutes and four and four-fifths seconds. In 1915, Regret became the first filly (and only one of three in total) to win the race. This, too, resulted in numerous attention-grabbing headlines in newspapers throughout the country. The headlines seemed bolder, larger than real life, for a New York society figure, Harry Payne Whitney, owned the filly. Regret gave the Derby sex appeal with her defeat of the males, and Whitney gave the Derby the cachet of his wealth.

Legend tells how men at Whitney’s farm rang a large bell outdoors in honor of Regret winning the race: a bell ringing that resounded with this new combination of Northeastern money and Bluegrass horses. This story implied incorrectly, however, that Regret was foaled and raised in Kentucky. Actually, she was a product of Whitney’s farm in New Jersey. Whitney did not transfer his breeding operations to the Bluegrass until after her birth. By that time, he, like a growing number of turfmen, had accepted the notion that his horse farm belonged in the Bluegrass. Robert Aitcheson Alexander and the Bruce brothers would have heartily approved.

During the 1920s, Winn introduced the singing of “My Old Kentucky Home” prior to the running of the derby, thus firming up imagined notions of the antebellum South with the race. But this did not occur until at least a decade after the notion of a Southern identity had taken hold of Bluegrass horse country. Horse-farm country anticipated the cultural turn that the Kentucky Derby would take and saved the Kentucky horse industry in the process.19

The increasing appeal of Bluegrass land among these outside capitalists made all the difference for Kentucky’s horse world. With each new infusion of outside wealth, the Bluegrass horse business expanded in ways that it had not done, on its own, during the latter part of the nineteenth century. The effect rippled throughout the entire community of Lexington and the surrounding towns. An infrastructure of ancillary businesses needed to support the horse business expanded with the growing number of farms. The horse business in central Kentucky increasingly entwined its fortunes with those of the local economy, which meant that more persons than just horse persons profited from this expansion. For example, the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder noted about horse auctions: “On the prices which obtain at them the prosperity of this community to some extent depends.”20

This evolving trend represented a startling turnaround from the previous estimation of the Bluegrass region in the eyes of these wealthy beholders. They slowly were letting go of that concern that the Bluegrass appeared too unstable for development. With this changing state of mind, they marched to the same drumbeat as did the readers of popular literature who had come to see Kentucky in more pleasing terms. Wealthy horse owners were no different than the larger society. Plantation literature had helped resituate the Bluegrass in their imaginations as an idealized Old South that their fortunes would enable them to purchase, as though buying the lifestyle of a country squire. Meanwhile, despite the obfuscation of plantation literature, the realities of Kentucky lawlessness and violence still continued to transpire at their usual reckless pace.

No one could have disputed that violence and a blatant disregard for the rule of law continued unabated in horse country; in fact, the scale appeared larger, not only in numbers of incidents, but also in the high profile of some of the victims. The killing of the Harpers in 1871 was a high-profile incident of one kind, but the killing of Kentucky governor William Goebel in 1900 ranked on another scale entirely.

Goebel himself had not been above violence. He had killed an opponent in a duel five years before his own death, shooting an ex-Confederate on the steps of a bank in northern Kentucky. Goebel was controversial: critics portrayed him as a demagogue, while others viewed him as a much-needed reformer who had waged war against corporations during the long depression of the 1890s. Goebel’s number one target had been the Louisville and Nashville Railroad (L&N), an entity that people widely accused of setting rates in a highhanded manner that placed increasing profits in the hands of the railroad owners.

Under leadership of August Belmont II, the L&N’s board of directors formed a cartel of conservative Democrats. Belmont has never been accused of any knowledge of the Goebel assassination, but he reportedly handpicked a candidate to oppose Goebel at the Democratic nominating convention the previous spring. The L&N financed a hardfought campaign against Goebel and his reformist wing of Democrats, all of whom had fallen under the spell of the populist William Jennings Bryan. When the convention opened, balloting quickly got out of hand and grew so raucous that the Democratic state chairman started to walk off the stage. He changed his mind when a representative from eastern Kentucky threatened to shoot him if he left his post.21

The L&N lobby next attempted to disrupt the proceedings by sending a mob to storm the stage. In a desperate attempt to restore order, some delegates began singing songs like “My Old Kentucky Home.” The ploy worked, and balloting continued, although not with a quick conclusion. Several days later, the Democrats remained split. Conservatives decided to depart for Lexington, where they nominated a former governor, John Y. Brown. Reformers steadfastly backed Goebel. Belmont’s reportedly handpicked candidate, P. Wat Hardin, never made it past the start of balloting.22

The man who actually won the closely contested election was a Republican, William S. Taylor. Brown came in third. But, when the General Assembly, with Democrats in control, decided to investigate the election, armed protestors favoring Taylor descended on Frankfort from eastern Kentucky. “In this atmosphere on January 30, 1900, Goebel was shot,” writes James C. Klotter. Taylor declared an emergency, called out the state militia, and ordered the legislature to reconvene in London. However, the Democrats refused to leave Frankfort and, while meeting secretly in a hotel, voted Goebel in as governor—shortly before he died of his wounds. “Two legislatures, two governors, and two militias vied for power, and civil war seemed possible,” Klotter writes. Four months later, in May, the courts decided that the Democrats had acted legally. Taylor fled the state. James Crepps Wickliffe Beckham succeeded Goebel as governor of the state.23

If wealthy turfmen harbored misgivings about these developments, their actions did not reveal the level of concern that had previously dissuaded capitalists from buying Bluegrass farms. Following Belmont’s relocation of Nursery Stud to Lexington in 1885, Lamon Harkness purchased Walnut Hall Farm in 1892. Harkness was a son of Stephen V. Harkness, a founder of the Standard Oil Company. The Ohioan planned to use his new Kentucky farm for breeding harness horses for racing purposes. James Keene purchased Castleton Farm that same year. Around the year 1898, William Collins Whitney took up Thoroughbred racing in a major way. John Madden became Whitney’s turf consultant. In his six years on the turf until his death in 1904, Whitney won major races in North America and abroad. Beginning in 1900, he leased La Belle Farm in Lexington. However, he never planned to maintain an operation in Kentucky permanently. He intended to move his horses back to New Jersey or Long Island as soon as he found a suitable location. In addition to the racing dynasty Whitney founded, his contributions to the turf included the restoration of the Saratoga Race Course; the once-grand racetrack had declined in reputation and significance, and Whitney almost single-handedly brought it back to its former status as a fashionable destination. His son Harry Payne Whitney brought this legacy with him to Kentucky when he purchased his Bluegrass farm during the racing career of Regret.24

Other outsiders to begin horse-farm operations during this time included Edward R. Bradley, the owner of a fabulous gambling casino in Florida, who founded Idle Hour Farm and would breed and own four Kentucky Derby winners: Behave Yourself, Bubbling Over, Burgoo King, and Broker’s Tip. Like Madden, Bradley began his working years as a steel mill laborer; later, he became a gold miner. He also became a gambler, opened his casino at Palm Beach, and garnered enormous wealth, which enabled him to buy his horse farm.

A Virginian, Arthur B. Hancock also moved to Kentucky after that operation began to eclipse the success of his father’s Ellerslie Farm in Virginia. Hancock named his Kentucky farm Claiborne.

With the plutocrats and robber barons falling increasingly under the spell of the newly crafted vision of the Bluegrass as the Old South, their arrival in Kentucky brought remarkable changes to the landscape. The homes, barns, and outbuildings they constructed on their new farms soon made it clear that they would dictate the appearance of horse country. None of the locally owned operations could compete with the scale or the expense of the construction that industrial and Wall Street wealth was bringing to the Bluegrass. “The average Kentucky stock farmer is not a millionaire, nor anywhere near it,” a writer for the Illustrated Sporting News wrote in 1903. Nonetheless, the local horsemen had been seeking such investment in their industry for decades following the war. Now it had begun to arrive, and, as the Sporting News observed, the average Kentucky stock farmer “welcomes the advent of the wealthy men of the North and East.”25

Two years later, in 1905, an important book titled Country Estates of the Blue Grass appeared. Published privately in Lexington by its lead author, Thomas A. Knight, this work represented the first known effort to extol the pleasing qualities of horse country in book form. Country Estates of the Blue Grass was a collection of stories about individual horse farms, describing them in photographs as well as text. For some time, Turf, Field and Farm had published articles accompanied by photographs about individual horse farms, with the photographs generally focused on the farm mansions. But, in the new book, all these alluring images came to the reader assembled in one package. The effect produced was powerful.

The introduction to Country Estates of the Blue Grass spoke to those desirous of escaping the urban sphere: “City life with its conventionalities, with its politics, its corruption, has been tested and found wanting. It was a pretty bauble which, when punctured by the two disturbing agencies, disappointment and ill health, lost its charm. So that now, we find the tide of progress turned towards the country.” The book presented Bluegrass scenes evocative of the Old South, showing African Americans engaged in farm labor. With photographs and stories like those in this book, Kentucky was slipping into the South as though it had always been there.26

It did not hurt the Bluegrass boosters’ cause that the colonial architectural style became fashionable across the country at this time: the style, characterized in great part by white-columned porticos, evoked the Greek Revival Southern mansions of the 1830s. Many of the old residences on Kentucky farms acquired this new look, among them the main residence at Woodburn Farm, which went from Italianate to a colonnaded facade. Since these residences already were large in comparison to the average home, the addition of columns bespoke what people imagined as representative of the South.

Country estates had become a fond refuge of the nation’s wealthy, as could be seen in the popularity of Newport, Rhode Island, where the rich had built luxurious “country” mansions for a retreat from urban life. With nostalgia for the Old South becoming popular, and with Kentucky looking more like the South than it ever had, the rich began to overlook their prior aversion to lawless Kentucky and began considering the Bluegrass for country estates. If any continued to see Kentucky as backward and perhaps too West to suit, Country Estates of the Blue Grass offered this advice: “[The Bluegrass was] not the country of yesterday … not the country where one was isolated from congenial companionship, from ease and every convenience, but the country of the Twentieth Century. The country, where one may meet cultured, well-bred friends, where one may find ease and luxury, where one may find every convenience that is found in the city.” This Bluegrass that the boosters promoted to the plutocrats was a sort of New South clad in the clothes of the Old South: an antebellum South with all the modern updates.27

The main residence at Woodburn Farm evolved from the Italianate villa to the colonnaded style during the Colonial Revival period. Sometime between 1904 and 1932, the Alexander family added porticos with colossal-order columns to the facade. During the first decade of the twenty-first century, the residence underwent a major renovation under its present owner, the former Kentucky governor Brereton Jones, whose wife, Libby, is an Alexander descendant. (Photograph by the author, 2009.)

As a consequence of this Southern imagery, a new class of landowner was emerging in central Kentucky: the wealthy absentee owner whose farm typically was becoming less diversified. The primary focus of these farms transitioned almost exclusively to breeding and raising racehorses. Kentucky horsemen wooed this new class of absentee owners and profited economically from the changing landscape. The locals benefited greatly, for a new professional class of Kentuckian was emerging in the Bluegrass—that of the expert or professional horsemen who assumed management of these farms. Within this expanding universe of horse farming, a number of ancillary businesses also emerged to provide veterinary care, banking services, horse feed, shoeing, and other specialties to the farms. Business in central Kentucky was picking up. Business leaders and horsemen of the Bluegrass had worked hard since the Civil War to reach this plateau, so it might have seemed ironic that fictional literature had allowed their efforts to attain this reality.

Growth and expansion, no matter how much they are desired, do not arrive without some measure of regret, however. Bluegrass residents experienced this troublesome side of the transition. Munsey’s Magazine might have suspected some feelings of sadness among the locals as they watched farm after farm pass to outsiders, for it noted in 1902: “Whatever of sentimental regret the Kentuckian may feel at the passing of historic estates into alien hands, he must admit that the infusion of new blood and the influx of outside capital has lent a decided impetus to stock breeding and training in the State—interests which, for various causes, had sadly declined.” Savvy horsemen—you might consider them local capitalists—nonetheless recognized the value of investment coming from outside the state, seeing this as the only way to expand their own wealth. Their wealth was founded only in agriculture, an imbalance that had rendered them noncompetitive with the industrial wealth of Northeastern turfmen. Munsey’s certainly recognized this imbalance when writing: “The newcomer, with unlimited capital at his back, has been able to accomplish in months what the Kentucky breeder, handicapped in many instances by lack of means, could scarcely have achieved in years.”28

Sanford and Belmont had pioneered the way into Bluegrass Kentucky from New Jersey and New York. Keene had perfected the way with his highly successful Castleton Farm. Taking notice of the rising trend for New York horse owners to build their farms elsewhere, the Brooklyn Eagle published an article in 1902 with the headline “A Horse Owners’ Exodus from Long Island Feared.” The subtitle read “Will Long Island, So Long Famous as the Home of the Trotter and Runner, Lose Its Prestige?” The article told how William Collins Whitney and August Belmont II were leading their peers to Aiken, South Carolina, for winter quarters. They were searching out more desirable land for the winter training of their racehorses in the same way they had sought out Bluegrass land for their mares and foals.29

A major change that these moguls brought to the Bluegrass landscape was the amalgamation of smaller farms into large estates. Munsey’s Magazine observed these changes to the landscape and noted: “The old fashioned stock farm of a few hundred acres, from which came trotters and racers famous in the annals of track and turf, is disappearing. It is being swallowed up in the great modern estate, baronial in extent and perfect in equipment. For instance, eight of the old farms were joined to make the splendid domain of Walnut Hall, with its two thousand acres of unsurpassed land.”30

Big characterized the great modern estates of outside investors whose ambitions were large, whose egos were larger, and whose bankrolls were largest of all. The greatest ambitions of all belonged to James Ben Ali Haggin, a native Kentuckian who, as previously noted, had gone west to work as a lawyer, then became a mining king. Haggin also had become the largest breeder of Thoroughbreds in North America with a vast stock operation in California and a much smaller farm at Elmendorf in Lexington. Eventually deciding, owing to the great cost of shipping horses east across the country, to consolidate his operations in Kentucky, he moved his stock to Elmendorf Farm in Lexington in 1898. The six thousand acres that he owned at the point of this consolidation, and another fifteen hundred acres that he leased, became home to some 800 broodmares, another 450 fillies under four years of age, and 23 stallions. “It is a gigantic plant which Mr. Haggin has established here,” reported the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder.31

Haggin followed the pattern of Harkness at Walnut Hall Farm, buying up farms all around the original five hundred acres of Elmendorf. The landscape as it looked in the neighborhood of Elmendorf prior to this momentous change had been many small farms under cultivation for crops of wheat, corn, tobacco, and hemp. On each farm, the owner lived as a permanent resident. Over the next seven years, Haggin, an absentee owner whose main residence was now New York, rearranged these farms into one vast expanse of pasture through which ran many service roads. He also built numerous stock barns.32

“And from a series of unimproved, disconnected farms, many of them unattractive, has been evolved an estate on which a king might live and be satisfied,” flowed a description in the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder. “Hundreds of workmen are daily adding to its improvements, yet other miles of magnificent roadway are being constructed between its stretches of beautiful pasture-land, thousands of trees are being planted, new buildings are being erected….” But not all these farms that Haggin bought had been unattractive. In 1907, he acquired Hira Villa at an auction held at the front door of the Fayette County Courthouse. Hira Villa was a Thoroughbred breeding farm on the Huffman Mill Pike formerly owned by the late Major Barak Thomas. A large crowd of farmers and horseman attended the auction, at which bidding began at $100 an acre. Haggin had the funds to outbid them all, running the price up to $181.25 an acre, for a total of $17,662.50 for approximately ninety-eight acres.33

The final touch was the Greek Revival mansion that Haggin built for his new bride, Pearl Vorhies of Versailles, Kentucky, twenty-eight years old when she married Haggin, himself seventy-four. Haggin reportedly built the residence as a country retreat in keeping with the trend for country estates. No other horse farm in Lexington made quite the statement that this residence, named Green Hills, did concerning Bluegrass Kentucky’s newly evolving Southern identity. Woodburn Stud, which recently had been remodeled with Grecian columns added to the facade, was no longer active as a horse farm by the twentieth century; thus, Green Hills took over as the representative mansion in this newly minted Southern state. The Green Hills mansion became a Bluegrass showplace, an attraction that drew the curious. Elmendorf Farm received anywhere from one hundred visitors or more every day, as the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder reported: “To the casual sightseer the feature of chiefest [sic] interest is the Haggin residence.” With such a massive stone structure and Greek Revival portico to set the record straight, there could be little doubt in the popular imagination that Bluegrass Kentucky existed as a holdover from the Old South. The Illustrated Sporting News affirmed this notion, declaring Green Hills “the typical Southern style of residence.”34

The Haggins visited Green Hills every autumn, traveling from New York in their private railroad car, which reached journey’s end on a spur of track close by the mansion. When in residence, they gave parties that people of their day agreed were some of the most celebrated in central Kentucky. They organized dinner and dancing for some 150–200 persons at these social events, with Haggin importing orchestras to Lexington. He also brought his entire domestic staff from New York when they visited. With the Haggins, New York social life found a satellite home in horse country. They established a cultural pattern for future horse-farm owners.35

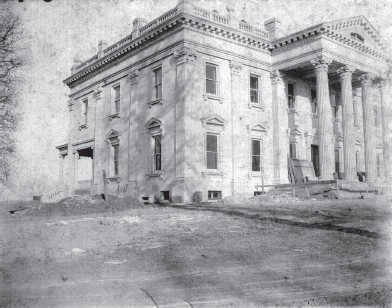

James Ben Ali Haggin purchased Elmendorf Farm in 1897 and built this $300,000 mansion, which he called Green Hills, for his new wife, the former Pearl Vorhies of Versailles. The mansion was a Bluegrass showplace, its massive structure and Greek Revival portico drawing praise as “the typical Southern style of residence” (Illustrated Sporting News 2, no. 31 [December 12, 1903]: 28). The Haggins traveled every autumn from New York to visit Elmendorf Farm and their Southern mansion. (Elmendorf Farm Photographic Collection, KUKAV-PA71M14–001, Special Collections, University of Kentucky.)

The dining room at Green Hills on Elmendorf Farm was rich in its design and appointments. (Elmendorf Farm Photographic Collection, KUKAV-PA71M14–013, Special Collections, University of Kentucky.)

The entrance hall at Green Hills on the Elmendorf Farm of James Ben Ali Haggin was ornately furnished with a marble table and a staircase leading to the second floor. (Elmendorf Farm Photographic Collection, KUKAV-PA71M14–011, Special Collections, University of Kentucky.)

Across Lexington from the Haggin estate, at another retreat along Winchester Road, Patchen Wilkes Farm, New York society amused itself in quite a different fashion—by staging a “Negro ball.” The hostess for the ball was the young Mrs. Rita Hernandez Stokes, the wife of the multimillionaire Earl Dodge Stokes. She had attracted considerable attention on the horse-show circuit at Newport and Long Branch, New Jersey, where she ruled as an expert driver and rider. While riding the show circuit, she had drawn the eye of Stokes, fifteen years her senior and heir to a fortune of $11 million. Reportedly, he fell in love with her after seeing her picture displayed in the Fifth Avenue window of a photographer’s studio. The two married in 1895, when she was nineteen years old. Depending on the stories, either Stokes gave Patchen Wilkes Farm to the new Mrs. Stokes, or she invested on her own initiative in this trotting-horse operation. Her Negro ball was an event steeped in the racism of the day and demonstrated how Northerners as well as Southerners viewed African Americans: as childlike, hapless, and appreciative of the patriarchal guidance the landowner offered. The Negro ball connected Kentucky with the Old South in the imaginations of landowners like the Stokeses.36

Rita Stokes imported friends from New York to observe the Negro ball. She also sent perfumed invitations to a Japanese man and his secretaries. He was the director general of that popular operetta The Mikado, which was playing in London and New York. Mrs. Stokes promised that she would prepare a Japanese dish for him during his stay at Patchen Wilkes, an indication that, like many women of her time, she viewed Asians as others incapable of fitting into Anglo-Saxon culture.37

As the New York Times reported, the Negro ball was the one social event that African Americans wished to attend. Mrs. Stokes had sent out two hundred invitations, and perhaps she did not send a sufficient number. The New York Times wrote: “Negroes from surrounding towns and cities have written asking for invitations to the ball.” Stokes told the newspaper that the entertainment at the ball charmed her immensely. She held the ball inside a brick horse barn that she had gaily decorated with bunting and flags.38

Workers at Patchen Wilkes laid down a canvas dance floor over half the barn floor; the other half held a table said to be 110 feet long and decorated with fruit and large cakes. Mrs. Stokes employed a caterer to “get up a supper such as negroes would enjoy,” the Times reported. Highlighting the dinner menu were roast shoat and sweet potatoes, fried fish and coffee, fruits, pickles, ice cream, and cake. “Jones’s colored band” furnished the entertainment. The evening also featured “buck dances” and a “cake walk” with prizes for contestants.39

Only four years after Isaac and Lucy Murphy had celebrated their tenth wedding anniversary with an elegant soiree described at great length in the Kentucky Leader, the New York Times and Mrs. Stokes had taken the African American community in Lexington back in time to before the Civil War. The black community in the Bluegrass had reverted from dining on quails with champignons and claret to “a supper such as negroes would enjoy” and all that this implied about the color line emerging after Plessy v. Ferguson. But, by the time Rita Stokes had installed herself on her Lexington horse farm, Murphy had died, black horsemen had disappeared almost entirely from the forefront of Thoroughbred racing, and the color line in this sport and on Bluegrass farms helped define how Northerners and Kentuckians were to view the identity of central Kentucky. Across the emerald-green pastures of the Bluegrass, the new identity was taking horse country back to notions of slavery and a patriarchal Old South.

While Rita Stokes amused herself with her Negro ball, her husband took his pleasure in his deepening interest in eugenics. This pseudoscience was founded on speculation that the human race can be improved by the selective breeding of only those persons sound of mind and body. It was not unlike the practice of breeding purebred horses, and, in fact, the mother of the Jockey Club member William Averell Harriman, Mary Williamson Averell Harriman (the widow of the railroad tycoon Edward Henry Harriman), purchased property on Long Island to be used as a site for building the Eugenics Record Office, opened in 1909. Stokes compiled his theories on eugenics in a book titled The Right to Be Well Born, published in New York in 1917. In it, he discussed his experiences as a horse breeder in Kentucky. Among his proposals was a government registry of persons in the laboring classes. He suggested that employers have access to genealogical records in this government registry so that they could estimate the amount and quality of work that laborers would be capable of undertaking.40

Stokes also thought that he had the answer for producing a lightweight “race” of jockeys. “All this starving, suffering and grilling these [jockey] boys undergo to keep down their weight can be avoided by breeding for smallness, strength and quick intelligence,” he wrote, “and a family of jockeys can be produced who will always be fit and ready to meet any racing requirements. It is just as easy to produce the jockey of the right size, weight, and with it all, intelligence, as it is to breed ponies or half-pound chickens and the like…. A ‘Jockey Registry’ will come some day on this principle.”41

The Stokeses had not created their Southern fancy in Lexington by constructing a Greek Revival mansion, as did the Haggins. Yet they lived the idea of the Southern landowner no less fully than had the Haggins by staging the Negro ball. The ball failed to become a Lexington tradition. It died with the marriage, Rita Stokes suing her husband for divorce in New York in 1900. When next heard from in 1911, Stokes had suffered serious injuries after arguing with two chorus girls in their apartment at Broadway and Eightieth Street in New York. The women shot at Stokes, and, almost immediately, three Japanese men ran into the apartment and attacked him using jujitsu. Stokes required surgery; a court acquitted the chorus girls. By that time, the Bluegrass appears to have moved on from recollections of Stokes and his wife as horse-farm owners in this Eden of the idyllic South.42

Little doubt remained, however, that wealthy outsiders were changing the farming landscape of Lexington, importing their spendthrift habits while building great manses, like Haggin’s, that rose in stark contrast to what Munsey’s Magazine called “the simpler tastes and standards of Kentucky yeomen.” Toward the end of her lifetime, and on the close of the nineteenth century, Josephine Clay saved an article in her scrapbook. It told how outside millionaires were replacing Kentuckians as the owners of major horse farms in the Bluegrass. It was not unusual to read in the newspapers about the sales of farms to outsiders, such as that of Oakwood Farm to “the latest confederation of Eastern millionaires to locate in the Blue Grass region.” The millionaires renamed the property Mill Stream, the renaming coming as their prerogative with the purchase of the property.43

Although Bluegrass residents had long desired an influx of outside capital to shore up horse breeding, some now felt conflicted about the presence of these outsiders. Haggin was not well liked. His marriage to a woman forty-six years his junior, with their engagement announced the night before the wedding, had shocked the community. He also engaged in a well-publicized boycott of the Kentucky Derby after arguing with Churchill Downs over the absence of bookmakers at the track. Horsemen in the Bluegrass and in New York accused him of ruining the public auctions by secretly running up the bidding on his own horses. Some Bluegrass residents complained that his buying up smaller farms in the neighborhood of Elmendorf took that land out of production for crops.

The community could not have it both ways, as the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder explained to its readership: “Not only have land owners been paid goodly sums for the six thousand acres of its expanse, but into the magnificent residence of its master have gone hundreds of thousands of dollars, into the beautiful stone fences which surround its entire area many other thousands, into its roadways amounts that would stagger if they were revealed. This money, whenever possible, has been spent here. Lexington contractors, Lexington business men have been the beneficiaries. Since the beginning of the establishment of Elmendorf the pauper list in Fayette county has been virtually abolished. Every man who wants work can find it there.”44

The transition of border-state Kentucky into a Kentucky of the antebellum South thus had its practical advantages for the locals, besides filling the needs of wealthy outsiders. However, all was not well in the Eden of the Old South. The slipping disease of the 1890s had returned. “Stamp out this plague,” pleaded the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder in desperation in 1906, for the incomes of all in the Bluegrass would be affected by this major economic loss. The publication insisted that someone take charge and formulate a plan whereby bacteriologists could study the malady and come up with some answers. “Raising and selling of blooded stock is one of the chief sources from which Kentucky derives her wealth. Such an industry as this should be fostered, encouraged, and protected by every possible means.” The industry remained at a loss, however, to determine what caused the disease—or how to stop its spread.45

Bluegrass horse breeders faced 1907 with tepid hope and a great amount of concern, praying that the disease would not strike again. But it returned to bedevil breeders for the second consecutive year. Just as in 1890, people suspected that the disease was contagious. Outsiders were becoming so leery of Kentucky that few were sending horses to race at Churchill Downs, some seventy miles away in Louisville. Then, finally, someone thought he’d found the source of the disease. A scientist in Copenhagen suggested that it was caused by a bacterium, which he called “short bacillus.” But nothing ever came of his conclusions. People remained mystified and at a loss about how to deal with the spontaneous abortions. They would occur again and again through the years, always affecting the Bluegrass economy. The abortions mimicked a number of diseases identified later in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, such as mare reproductive loss syndrome. But the cause of the nineteenth-century abortions was never specifically identified.46

At this same time, a phenomenon posing a still greater threat was building momentum. This was the social reform movement of the 1890s, which got only stronger as the twentieth century commenced. Even as the expanding class of multimillionaires was discovering an idyllic retreat in the Bluegrass, a greater number of Americans became determined to shut down horse racing nationwide. The reformers no longer focused their energies primarily on New York. Their influence had brought antiracing legislation in New Jersey in the early 1890s, followed by more legislation in Missouri, Kansas, Tennessee, and Washington, DC. Louisiana banned racing in 1908, although the legislators almost did not get the job done. Someone there reportedly poisoned or doped the food of two state senators who favored passage of an antiracing bill. The two were quite ill when they managed to show up for the vote; their colleagues practically had to give their ayes for them in order to pass the bill, 21–19. The next track to fall to reformers was the original Santa Anita racetrack in California. The Rockingham track in Salem, Massachusetts, followed. The number of operating racetracks went from 314 in 1897 to 25 by 1908.47

New York had survived thus far because August Belmont II had worked in tandem with state legislators for passage of the Percy-Gray law in 1895. Belmont’s supporters claimed that he saved the turf from inevitable ruin with this bill and that he also laid the foundation for an expanded breeding industry in New York. The rallying cry in attempting to defuse the reformers had long been that racing served a necessary purpose as a testing ground for the improvement of the breed; the idea was that all farmers would benefit from an improved Thoroughbred, perhaps in pulling their plows.

Organized Thoroughbred racing emerged a winner with the Percy-Gray law, which declared gambling illegal away from racetracks without specifically addressing gambling at the tracks. Belmont’s detractors claimed that this bill had to do not so much with improving the breed as with consolidating control of gambling at metropolitan tracks like Morris Park (and, following 1905, Belmont Park) that Belmont and his colleagues owned and operated. The cry went up: “One law for August Belmont and another for [offtrack gambling interests].” Some have suggested that a number of the gravest scandals surrounded the enactment of this law. At the very least, it appeared to favor one segment of elite society.48

Belmont’s influence in the legislature went only so far, however. Like everyone else involved in Thoroughbred racing, he ran headlong into a wall that would not budge in the form of New York governor Charles Evan Hughes. By 1908, Hughes had mounted an offense against the racetracks based on the idea that these venues should not enjoy special status exempting them from gambling. A man highly in tune with reformist aspirations, he cited the evils and demoralizing influence attendant on gambling. He organized church leaders and progressives to work against racetrack gambling, arguing that the New York constitution held gambling illegal and made no exception of racetracks despite the Percy-Gray law. On June 11, 1908, Hughes signed the Hart-Agnew Bill into law, and, with it, betting became illegal everywhere in New York, including at the racetracks.49

Racing enthusiasts discovered a loophole, however, that made oral betting possible. These bets, made by one patron with another, eliminated the bookmakers but appeared to be permissible under the new law. Consequently, the New York racetracks limped along for the next two years. In 1910, the system crashed. Hughes signed a new bill, the Agnew-Perkins legislation, that made the racetracks responsible for enforcing the Hart-Agnew antigambling law. Racing in New York shut down completely for the next two and a half years after the final race of the day at Saratoga on August 31, 1910.50

Belmont, never one to overlook the possibilities that might lie with his influence in the state legislature, appears to have tried his luck again in Albany. He was accused of slipping in and out of the back rooms of the state capital when the Hart-Agnew law came up for the vote. He supposedly turned up at Albany with an open pocketbook, which his accusers said he proffered to state legislators. The amount mentioned consisted of a “corruption fund” of $500,000 intended for bribes. One state senator claimed that the Jockey Club offered him a bribe of $100,000 to vote against the bill.51

As the chairman of the powerful Jockey Club, Belmont, and several others from that organization, had indeed walked the legislative halls. However, they insisted that their intention had been only to lobby against the bill. They swore during an investigation that the money in question had been paid out for legal expenses and publicity and “denied under oath that any of this money had been used for any but legitimate purposes.” Nearly three years after the Hart-Agnew bill became law, a news item told how “the Jockey Club and its eight racing association members are completely exonerated of attempts to bribe the legislators to the end of bringing about the defeat of the Hart-Agnew anti–race track bill in 1908.” Their denials brought an end to the investigation.52

Meantime, Kentucky horsemen were taking no chances of their sport appearing corrupt or operating in a state of disorder. Horsemen cooperated with state legislators in the passage of a Kentucky Racing Commission Act in 1906, creating an authority that would write state racing rules as well as assign noncompeting racing dates to the various tracks. Ironically, the new racing commission emerged amid accusations of ignoble activity having inspired the formation of this ruling body. According to these accusations, a powerful alliance of track operators and state government officials combined to form the commission in order to protect Churchill Downs from competition.53

Concern for the protection of Churchill Downs actually extended to all racing in Kentucky. An ownership group known as the Western Jockey Club, or the “Cella-Adler-Tilles gang,” had attempted to open the Douglas Park Jockey Club in Louisville in direct conflict with the racing days that Churchill Downs enjoyed. Breeders in Lexington feared the infiltration of this group. According to the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder: “They would gradually endeavor to extend their interests, and their influence to other sections of the state. To have a sport … degraded through the management of such a crowd would indeed be a sorry reflection on the state…. We would rather see the Lexington track cut up and sold for building lots and forever lost to racing than to see this crowd get control of it.”54

Douglas Park sued and sought an injunction against the racing commission for refusing it the race dates sought. It lost. The Daily Racing Form commented: “As the home of the thoroughbred it is well for Kentucky that racing in that state is to be controlled by men who have at heart the love of a high class sport for its own sake.” The suspicion remained with some, however, that these same men had used their power to shut Douglas Park out of direct competition with Louisville’s premier track. People believed that the state racing commission emerged, with power to award racing dates, in order to prevent simultaneous race meets, “with full power over all tracks at which running races are held,” as the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder noted.55

Racing in Kentucky persevered under the authority of the Kentucky Racing Commission during these challenging times. Nonetheless, the sport suffered great losses during the blackout that extended nearly nationwide. The financial downturn in money paid to owners of winning horses at the nation’s racetracks showed how much value the sport had lost from 1906 through 1911. In 1906, $5.4 million in purse money had been distributed in North America. In 1911, the figure fell to $2.3 million, with none of this money coming from New York, where tracks had closed. New York tracks went from paying out a total of $1,582,871 in purses to horse owners in 1908, to $790,650 in 1910, to nothing in 1911. Small wonder that owners like Haggin began to sell off their breeding and racing stock. Speculating that depressed prices at horse auctions would drive breeders out of the business, the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder noted in 1905 how “the disastrous influence of the recent legislation against racing is already felt.” A racing editor for another publication predicted that, if racing ever returned on its former scale, “the process of rehabilitation will necessarily be slow in contrast to the swiftness with which values were destroyed under the blighting influences of the fanatical crusades that have been a feature of American politics of late.”56

No one knew whether racing ever would be revived on a national scale. With this in mind, some of the wealthiest horse owners in New York had begun sending their stables to Europe to race even prior to the blackout, fearing its effects. Others got out of the sport entirely, some dumping their horses at cheap prices on the South American markets. Elmendorf had been disposing of Thoroughbreds since 1908, after the Hart-Agnew bill passed. In 1909, the farm sent horses by ship to Argentina. In 1912, Haggin sent eighteen broodmares and twelve foals to sell near Berlin. Haggin, a man who had made a fortune in risky mining ventures, had come to suspect that the future of horse racing no longer stood as a solid bet.57

The Kentucky Association track opened in Lexington in 1828 with the support of men like Henry Clay and Robert Aitcheson Alexander. The accomplished racehorse Lexington started off his career here. Before the track closed for good in 1933, Man o’ War made a farewell appearance in 1920 (although he never raced in Kentucky). (Postcard from the collection of the University of Kentucky Libraries, Special Collections.)

Patrons of racing in Lexington already knew what it was like to go without their sport. The Kentucky Association track had closed in 1898, not as a result of antigambling legislation, but because the track had fallen into a financial tailspin after the Panic of 1893. “The panic … forced many horses upon the market,” the Kentucky Farmer and Breeder related. “Prices ran low, breeding ceased, and as a consequence stock farms were closed out, the market was glutted and in many instances horses did not bring the freight and expense bills of the sale. So demoralized were the conditions of the horse trade from 1895 to 1900 that breeding to a considerable extent was abandoned all over the country.” The decline in breeding directly affected racing at the track in Lexington, and, consequently, it closed it gates. It took an outside capitalist—the Pittsburgh steel baron Sam Brown—to come up with the money needed to bring racing back to Lexington. Local horsemen did not have sufficient money among themselves.58

However, with Kentucky racing up and running again by 1905 and the state’s first racing commission founded as a beacon of order, the sport appeared on better ground in Kentucky than anywhere else. Kentucky’s patrons of racing had believed that their sport would survive nearly any threat, and even New York’s Spirit of the Times had once remarked: “Kentucky is the last state in the Union where laws even incidentally adverse to that interest could be enacted.” Churchill Downs soon found out that this was not the case. In 1907, Winn, its owner/ operator, became engaged in a desperate struggle to head off reformers from shuttering his track. They had managed to bring about a ban on bookmaking that year at the Louisville track. Since this was the only form of wagering at Churchill Downs, Winn had acted quickly to find an alternative form of gambling in order to save the derby and the track. He was successful in this, tracking down four pari-mutuel machines that had been tried out, unsuccessfully, some years earlier at the track. In his memoir, he wrote that these four machines saved racing in Louisville. They accomplished at Churchill Downs what Sam Brown had when saving the sport for Lexington.59

In Lexington, Sam Brown was to the Kentucky Association track what Matt Winn was to Churchill Downs. Racing had returned to the Bluegrass thanks to him. However, Bluegrass horsemen never felt completely certain that their business could or would continue in the face of the nationwide antiracing sentiment and the blackout of the sport that followed. They felt that they needed state tax relief to help provide a more secure future. Toward this end, horsemen proposed a plan that would shift the greatest burden of the tax on equine stud fees to the “scrub” (non-Thoroughbred) stock of eastern Kentucky, freeing tax liability from Bluegrass Thoroughbred stock. With this proposal, not only were Bluegrass horsemen setting their horses apart from all others; they were completing whatever the plantation school of fiction might have left unfinished in nailing down the notion that the Bluegrass was, indeed, different from the feuding Eastern portion of the state, where the scrub stock could be found.60

The group worked quickly to deflect any criticism that its proposal favored the wealthier section of Kentucky, “the men able to own the best stock in the state as against the less favored mountain regions.” Public perception indeed would have made it incumbent on these men to soften the class issue at stake, for a senator from Woodford County in the Bluegrass had gone further than they had, suggesting that the breeding of scrub horses be prohibited in Kentucky. Bluegrass horsemen consequently formed a “Breeding Bureau” and planned to acquire three Thoroughbred stallions to consign to those regions of Kentucky “where the general class of horses is badly in need of improvement.” This meant the mountains.61

New York horsemen already had formed a similar bureau, hoping to sway public opinion in favor of racing in their state. The Kentucky Farmer and Breeder commented:

The masses of the people will not much longer accept racing purely for its own sake with the gambling accompaniments which are necessary to its success…. But if the people of the country become educated to the fact that the thoroughbred horse is the most valuable of all breeds of horses, that the infusion of his blood can do more to elevate the general class of horses … and this breed can be kept pure and can reach its highest state of perfection only on condition that racing be allowed and that wealthy men continue to import the best stock of other countries in order to win the classic events of our turf, then we have a tangible ground on which to advocate racing and on which to make an appeal for its continuance.62

Racing remained in the grip of the shutdown when someone, perhaps Belmont, thought it advisable to hold a dinner in New York simply to boost the morale of horse owners who had been denied the pleasure of their sport. Some three hundred patrons of the sport from throughout the United States convened in 1911 at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, where Belmont, the host of the affair, was identified as “Chairman of the Jockey Club, which controls racing throughout the country.” A statement like that left little doubt about the wide scope of the Jockey Club’s control. Belmont announced a plan to offer the federal government six Thoroughbred stallions to use in starting a National Breeding Bureau since breeding bureaus appeared to be the weapon of last resort in fighting antigambling forces. Belmont told the gathering: “Upholding [racing] and doing it justice by passing intelligent criticism upon racing faults is right and we should frown upon the bigot whose gloomy pessimism would turn God’s flowers of the field to a monotonous gray.” Consoling one another seemed all they could do at the time.63

Thoroughbred racing was not going to return to New York as long as Hughes remained governor. That fact seemed certain. But, when Hughes ended his term in 1910 to assume a post as an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, supporters of racing might have begun to glimpse some hope. A test case that arose in 1912 out of gambling on a steeplechase meeting at Belmont Park did, in fact, lead in a positive direction for the sport. The court found that a racing association could not be held liable for illegal gambling if it did not realize that such gambling was taking place on racetrack grounds. The court of appeals in New York dismissed an appeal filed by reform interests, with the result that racing returned May 30, 1913, to Belmont Park. Bennett Liebman, writing about racing’s travails throughout the Progressive Era in New York, has posited that the courts’ actions in continually stepping in to protect horse racing in that state actually rescued the sport, despite the temporary effect of repressive laws. The effect of racing’s return in New York trickled down directly to the Bluegrass horse business, which had been struggling in the economic downturn resulting from nationwide progressive reform.64

Not all in the sport had given up hope that racing would return to New York. Following the death of William Collins Whitney in 1904, his son, Harry Payne Whitney, was the leading buyer of his horses at the dispersal held by the Fasig-Tipton Company at Madison Square Garden. The younger Whitney initially removed his father’s breeding operation from La Belle Stud, leased in Lexington, to Brookdale Farm, leased in Red Bank, New Jersey. But, ten years later, he changed his mind, and he, too, began buying land near Lexington to develop into a horse farm. If he had changed his mind sooner, his Derby-winning filly Regret might have been born and raised on the Kentucky farm. Little mention was made of her New Jersey origins when the legend evolved about horsemen ringing the bell at Whitney’s new Kentucky farm in honor of her winning the derby. There must have seemed no point in spoiling a good story. She was Harry Payne Whitney’s horse, and he had set up a horse farm in Kentucky, if belatedly. That was all that mattered.65

With racing returned to New York, with the Kentucky Derby receiving national attention, and with increasing numbers of wealthy outsiders heeding the siren call of the Bluegrass region, the professional class of horsemen in central Kentucky had reason enough to laud their work in bringing the racehorse world back home to their state. In their time, in their era, they would not have thought to extend credit beyond themselves, for it had been men like them who had changed the sport from a gentlemen’s pursuit into an industry that Kentucky had reclaimed from the Northeast.

With this, however, they would have overlooked the role that plantation fiction played in revising estimations of horse country to eclipse the lawlessness and violence. They also would have overlooked the role of women, for, with rare exceptions, women like Josephine Clay had been denied a visible place in racing. Thus, horsemen failed to grasp how women sympathetic to the old Confederacy of Southern states might have had the greatest success in reclaiming the horse business for the Bluegrass.

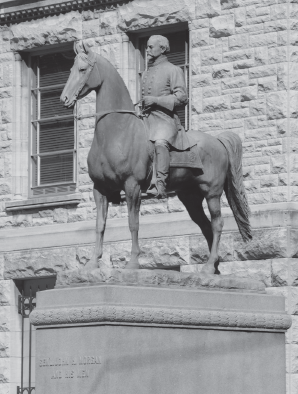

However, women assured the Old South myth a place in reconstructed history when they bronzed it and placed it in the form of a memorial to a Confederate general at the courthouse square in Lexington. It was women of the United Daughters of the Confederacy who conceived the idea and raised the money for a memorial to General John Hunt Morgan astride his favorite horse. Wives, daughters, sisters, and nieces from families associated with Thoroughbred racing or breeding stood as the driving force to bring this memorial to fruition. And it was General Morgan’s memorial that stood as proof to Northerners that Bluegrass horse country was, indeed, a place of the Old South, a place where the “mystic chords of memory” invoked a culture that bespoke the lifestyle of the Southern cavalier—the Southern colonels and their ladies—that the wealthy might acquire by purchasing Bluegrass horse farms.

And this, as Taylor and Blight have noted, was a fact that Northerners wished to know even as Lost Cause fervor swept the nation. Lexington chose for its hero an officer from the losing side, but this decision supported the horse industry. Early in the twentieth century, when Lexington’s citizens, in combination with outsiders, rewrote Bluegrass history, a Confederate officer of General Morgan’s notoriety represented the perfect choice.66

General Morgan, born in Alabama and raised in Lexington, a close friend of Sanders and Benjamin Bruce and the husband of their sister, Rebecca, had failed to make it through the war. He was shot and killed at Greeneville, Tennessee, in 1864 during an attempted escape while awaiting a court of inquiry hearing. Days earlier, he had been suspended from command of his men. The inquiry had been ordered on reports that his men had robbed and looted on their final raid through Kentucky. It was a wonder that a Bluegrass horseman had not shot Morgan first: his men burned barns at the association track and had stolen racehorses and bloodstock from Clay, Alexander, and others. Lexington residents made a habit of boarding up their houses when they learned that Morgan was headed their way. They feared him and his men.67