Kentucky, racehorses, and Southern colonels just seem to go together naturally. Whether picturing Bluegrass horse farms or their close relative, the Kentucky Derby, many of us cannot summon one of those images without calling up all three. The goateed colonel holds the dominant position in the landscape of imagination that defines this central portion of Kentucky. Place the colonel on the colonnaded plaza of a grand mansion, surround him with guests and family sipping juleps served on silver trays, indulge him in his telling of tall tales about fast horses, and the image evokes Kentucky horse country.

This picture has been stamped so indelibly on notions of Bluegrass Thoroughbred culture that not even Kentuckians seem aware that horse country did not historically fit this image. To borrow a phrase from Michael Kammen, who argues that memory is reconstructed as history, the “mystic chords of memory” have failed to serve Bluegrass history in any faithful way. True, the mineral-rich soil, water, and bluegrass, the latter known scientifically as Poa pratensis, did spawn a significant racehorse business during the antebellum period. However, this business as it stood in Kentucky rocked precariously on the edge of decline during the first forty or fifty postbellum years. True, Thoroughbred horse racing experienced an explosive growth in popularity during this era. However, at the same time, Kentucky lost its dominant position as the locus for the breeding of racehorses. Modern new farms were arising in New Jersey and New York, fragmenting the business among multiple states.1

A generation would pass before Bluegrass Kentuckians managed to return the center of the Thoroughbred breeding world to their region. This mattered greatly to them, primarily because of the direct and residual income that a Bluegrass-centered industry could bring to the state. We all know how the story turned out: that horse breeding became the commonwealth’s signature agricultural industry, bringing worldwide respect and recognition to the state. Today, the Kentucky horse industry has an economic impact that is estimated to be $4 billion, not to mention the $8.8 billion in associated tourism that it brings in. Had the story turned out differently, the commonwealth might never have realized the wealth in modern times that horses have brought to it. The victory was hard-won.2

Many are unaware that, for decades, Kentucky horsemen engaged in a power struggle with the new money in the sport—those industrialists and capitalists of New York who were spending money at unprecedented levels to develop horse farms in the Northeast. The architecture and design of these new horse-breeding operations in New Jersey and New York outshone anything existent in Kentucky, even the famed Woodburn Farm. The latter, a premier breeding operation located in Woodford County and known throughout the United States even before the Civil War, stood the leading stallions in the United States at stud. However, Woodburn Farm could not boast of the fancy appointments of these nouveau racehorse operations rising in the Northeast. The agricultural wealth of Kentuckians simply could not compete with the vast array of industrial wealth in the Northeast. Only one among Kentucky’s horse breeders, Robert Aitcheson Alexander, who owned Woodburn Farm, possessed a fortune founded in industry. The numerous industrialists from the Northeast who were getting into the sport outnumbered him. And it was to the Northeast that the center of the sport had swung, with the new men of the turf breeding their own mares to their own stallions far removed from traditional horse country.

Permanent loss of this business would have affected the Bluegrass region in myriad ways, beginning with the physical landscape that has become iconic to horse country; this iconography helps draw tourism and other business. The physical landscape that marks central Kentucky as horse country includes the multitude of manicured farms, such as Calumet, that exist close to the city and can be seen without having to travel too far from downtown Lexington. The regional iconography extends to the miles of board fences signifying horses, the architecturally astounding horse barns, and the emerald-green pastures populated with bloodstock that is valued in the multimillions of dollars. As for the economic impact, earnings from horse farms ripple through the regional and state economy in numerous directions, ranging from veterinary services and hay and feed suppliers to grocery stores, office supply companies, automobile dealerships, insurance companies, and shopping malls, bringing a better lifestyle to residents regardless of whether they are directly involved in the horse economy. If the story behind the making of Kentucky’s horse business provides a usable past, it is the cautionary tale of how integral this business remains to the state’s economy—and how, without protection, it could easily be snatched away by other states eager to grab the wealth.

The overarching theme behind this struggle to build a Kentucky horse industry was the realization among the region’s horsemen that they could not begin to do so without luring the big money from outside capitalists into central Kentucky. And it is my contention in this book that the money began to flow into Bluegrass Kentucky only after both locals and outsiders embraced a popular plantation myth that gave the region a neo-Southern identity. Ironically, this occurred some thirty-five to forty years after the end of the Civil War and the disappearance of the Old South. Bluegrass Kentucky’s new identity had fortunate economic consequences, as it negated the region’s notorious reputation for violence and lawlessness, thus bringing business to horse country. But, at the same time, this altered identity excluded African Americans from participation in the new horse industry. The new identity also rewrote the region’s history, for it ignored the role the commonwealth had played as a loyal part of the United States during the Civil War. A mistaken notion grew that Kentucky had remained neutral throughout the war.

The neo-Southern image was a cleverly crafted picture, situating the Bluegrass within an Eden of smoothly operating plantations where the horses ran fast, the living seemed ideal, and all African Americans occupied servile positions of offering juleps to the colonels as the white folk relaxed in the shade of columned mansions. This picture grew in direct contrast to the highly visible sphere that blacks had occupied as star athletes of the sport, some, like the jockey Isaac Murphy, becoming wealthy in the generation following freedom.

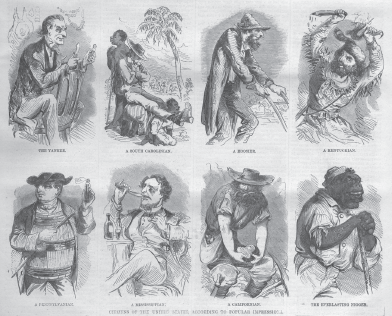

“Citizens of the United States according to Popular Impressions.” Although highly offensive to modern sensibilities, this illustration depicts stereotypes associated in 1867 with a variety of Americans. The popular image of Kentuckians retained the old notions of the Western frontier: a wild, uncivilized character in coonskin cap with a hunting knife in one hand and a recently taken scalp in the other. Bluegrass Kentucky would not begin to acquire its civilized and highly polished Southern identity until decades later. (Harper’s Weekly, January 12, 1867, 29.)

Today, some persons might argue that, as a slaveholding state, Kentucky shared a common ideology and common characteristics with the seceded South even if it had remained loyal to the United States. Commonly shared interests did exist; however, Americans of that era did not readily view Kentucky as Southern. Neither did all Kentuckians, who were notoriously divided on who and what they were. Kentucky was a state of multiple regions, each with its own identity. The state’s overall identity was imprecise and vague.

We’ve all heard the story that Kentucky did not secede from the Union—until after the war was over. Arguably, the state’s central region, the Bluegrass horse country, did not begin to associate with a Confederate identity until sometime after the Civil War. The historian Anne Marshall has pointed out that this turn appeared quite strange indeed, given that it brought Kentuckians to embrace the war’s losing side when in reality Kentucky had fought on the winning side. Historians are beginning to show how and why this notion expanded within the regional consciousness.3

Generations of Kentuckians once explained away this change of mind as pure resentment over atrocities that the U.S. Army committed while stationed in the commonwealth. E. Merton Coulter had promulgated this theory in his history of Kentucky after the Civil War. As a Southern man of his times—the 1920s and 1930s—he had viewed the Kentucky conundrum through a racist and neo-Confederate prism. According to his analysis, Kentuckians turned their backs on the federal government and wished, in retrospect, that they had fought on the side of the Confederate states. They made their feelings clear when they assimilated a Confederate identity after the war was over. Revisionists have effectively argued against Coulter’s thesis. But, until recently, little work had been done to explain whether and why, if Coulter’s theory no longer held up, Kentucky had actually gone over to the side that had lost.4

More recent historians of Kentucky generally have agreed that, following the war, those Kentuckians living at least in the central portion of the state—the Bluegrass—increasingly identified with the Southern states. However, they do not agree specifically on when, how, or why this turn occurred. For example, Marshall has argued that white Kentuckians came to imagine their state as Confederate by embracing racial violence, Democratic rallies, and the myth of the Lost Cause, all of which suggested a Southern and Confederate identity. Luke Edward Harlow has connected a proslavery theology in the politics of Kentuckians—following the demise of slavery—as a link to a Confederate identity. In his argument, Kentuckians reconfigured white religious understandings of slavery from before the war into a justification for Jim Crow practices long after the war.5

I argue in this study that Bluegrass horsemen joined with outsiders in assigning a Southern identity to their region early in the twentieth century, when doing so suited the nostalgic needs of white Americans generally and the economic needs of Bluegrass horsemen specifically.

Americans at the turn of the twentieth century felt beleaguered. They longed for a more wholesome and orderly lifestyle that they believed might have existed in the past. A postwar, industrialized age that people had hoped would create an easier lifestyle for all was accomplishing the opposite: creating angst because machines replaced traditional craftsmen, because large corporations devoured family businesses, and because industrialists, capitalists, and the financial speculators on Wall Street had cornered the majority of American wealth. These wealthy folk might have seemed to inhabit an ideal sphere, given their magnificent mansions, their elegant parties, and their showy stables of racehorses. But not even the very rich could escape the rising angst of the times. They lived in a world fraught with violent labor strikes directed against their industries, with race riots in their city streets, and with servant problems in the private sphere of their homes.

Small wonder, then, that the upper class as well as the middle class found an escape in novels and nonfiction idealizing the past. This past came popularly to life as an imagined antebellum Southern lifestyle. As depicted on the printed page, this antebellum world appeared as quite the opposite of the impersonal world that Americans knew at the turn of the twentieth century. The Southern cavalier ruled his plantation with a fatherly kindness that benefited both his family and his servants. The only turmoil to be found in this imagined world might have been a daughter’s love affair with a Yankee, a love affair that crossed taboo geographic lines. As it happened, the Bluegrass region of Kentucky became associated with this cavalier South thanks to a group of esteemed and highly popular writers whose work pictured central Kentucky in these terms. Outsiders and regional inhabitants alike began to picture horse country in a new and different way that brought a great economic boom to the region’s equine business. This boom turned the Bluegrass into the horse capital of the world.

Bluegrass horse and business interests had been trying since the Civil War to attract outside capital to the region. But they never were successful, largely owing to the violence and lawlessness that kept this capital away. Not until Bluegrass Kentucky evolved as Southern in the popular imagination did those outsiders with big money change their minds about buying into the region’s horse-farm land. When the outsiders began buying up Bluegrass land, they helped create a horse-farm iconography with the lavish improvements they made to the land. The mining king James Ben Ali Haggin at Elmendorf Farm and the Wall Street wizard James Keene at Castleton Farm, both of these Thoroughbred operations, and the Standard Oil heir Lamon Harkness, who created a trotting-horse estate at Walnut Hall Farm, came first. More soon followed. As this study will show, an imagined construct of plantation life that quickly morphed into reality enabled the Bluegrass to acquire unusual cachet, thus regaining the power in the horse world that it had lost after the Civil War.

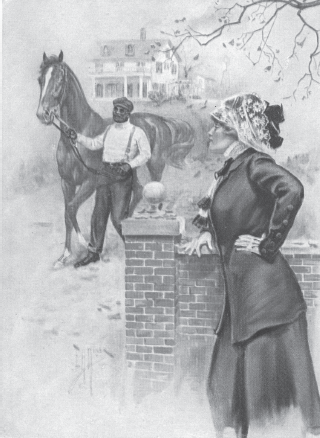

Iconic to Bluegrass Kentucky are images of well-bred horses, well-bred women, and Southern mansions. (Undated postcard from the collection of the author.)

Chapter 1 shows how Kentucky racehorse breeders got left behind in the new expansion of the sport even before the Civil War had ended. Racing shifted to the Northeast, Bluegrass breeders lost valuable horses to both armies as well as to guerrillas and outlaws, and the only plan of action for a productive future resided with Robert Aitcheson Alexander, the owner of Woodburn Farm, and his handpicked associates. However, not even Alexander could foresee the future faultlessly. He forfeited an opportunity to immediately align the interests of Kentucky horsemen with those in the Northeast when he ignored their requests to send his brilliant racehorse Asteroid to Saratoga Race Course. This apparent snub of the outsiders, new to Thoroughbred racing, turned out to haunt Kentucky’s breeding business. The New Yorkers eventually retired their brilliant racehorse, called Kentucky, to stand in New York. This portended a shift in horse breeding to the Northeast, following the sport of racing.

Chapter 2 describes the competition that breeders in central Kentucky faced in trying to join the expansion of Thoroughbred racing. Lavish, ultramodern horse farms began arising in New York and New Jersey. As well, Tennessee horse breeders quickly reestablished their business, giving Kentucky competition from the South. Bluegrass horsemen also faced major labor shortages after the war. Had they not found a way to lure labor back to the farms—by creating rural hamlets for the labor force—the horse business might never have progressed. The greatest assist to Kentucky’s horsemen, however, was in the voice they acquired in the publishing world of New York through Alexander’s associates, Sanders and Benjamin Bruce. The two brothers initiated marketing techniques that helped bring attention to Bluegrass farm country. These two set about trying to show how the natural advantages in Kentucky Bluegrass soil and water resulted in superior racehorses. However much attention their marketing efforts brought to the Bluegrass, these efforts still failed to bring the capitalists. The reputation for violence in the Bluegrass had stamped the region as too unstable for capital investment.

Chapter 3 demonstrates how the culture of violence and lawlessness made the Bluegrass region as unsafe for the wealthy landowner as it was for all others, including African Americans. It also reveals how even the wealthy landowners manipulated the culture of violence, going outside the law when it suited their purposes. The gentry class in the Bluegrass manipulated the Ku Klux Klan, according to the New York press. Events at Nantura Farm in Woodford County, adjacent to the famed Woodburn Farm, demonstrated the extent to which landowners went in following or mimicking KKK practices. Every lawless event, however, stacked up against the Bluegrass, making it that much harder for the region to regain its central position in horse breeding.

Chapter 4 brings to light the success and accomplishments of the African American horsemen who, in turn, brought recognition to Kentucky’s horse business. Recognition boosted the fragmented reputation of Kentucky as the cradle of the racehorse. African American jockeys and horse trainers were iconic to Kentucky’s horse country, and some of the most talented competed successfully against white riders in the Northeast. Black horsemen appeared to live protected lives apart from the violence raging against blacks in Kentucky. The most talented black jockey, Isaac Murphy, lived a lifestyle parallel to that of whites in Lexington and entertained with elaborate parties given at his mansion. But the recognition of their talent and way with horses given to black jockeys and trainers was never enough to bring the big money to the Bluegrass and to centralize the growing industry in the commonwealth. The business remained fragmented, with the majority of the largest, most productive farms lost to the Bluegrass.

Chapter 5 illuminates the tensions arising between Northeastern and Kentucky racing interests at the very time the sport underwent a nationwide expansion. This power struggle further fragmented the sport, with racing leaders in New York doing whatever they pleased to minimize the significance of competing interests in Kentucky. Nonetheless, the face of the sport was changing from the small sphere of the New York banker August Belmont and his acquaintances from industry and Wall Street. The sport had grown far beyond the vision they had held, to draw in mining kings and railroad industrialists of the West and Midwest. This expansion began to see increasing numbers of horse owners reaching down into the Bluegrass for stock to replenish their racing stables. Their object was to find a winning edge over an expanding competition base. However, with violence continuing unabated in the Bluegrass, none of these wealthy men moved their operations to the region. Consequently, only a few of the most fortunate Bluegrass horse breeders experienced financial wealth; the industry remained fragmented throughout a variety of states. A critical turn was August Belmont’s decision to move his breeding operation from Long Island to Lexington. Kentucky’s reputation for violence shone an unflattering spotlight on this move, for Belmont’s manager arrived in Lexington fully armed. With the reputation and the reality of violence continuing unabated in central Kentucky, Belmont’s move failed to initiate a run of capitalists on Bluegrass land.

Chapter 6 illuminates how the campaign of social reformers to shut down Thoroughbred racing throughout the United States would eventually tie in to Kentucky helping save and centralize the industry by manipulating the Southern myth. By the 1890s, the expansion of racing had brought fraudulent practices to the sport, drawing the attention of antigambling forces. By the early twentieth century, social reformers had persuaded various state legislatures to shut down racing in many jurisdictions, most notably in New York. A number of the wealthiest in racing sent their stables to Europe to race. But some held out the possibility that racing might return to New York. One was a Bluegrass entrepreneur named John Madden, whose life story was partly Horatio Alger and partly that of the physically fit, natural man that President Theodore Roosevelt believed was the only type that could return order and supremacy to white America. Madden began to draw the interest of wealthy men in racing. He sold them horses at fantastic prices, gaining their trust, not only because of his expert horsemanship, but also because he represented the pristine, natural, white American. He projected this popular image onto the Bluegrass region, helping create a notion that vied successfully with the debilitating picture that the antigambling forces had projected onto the sport. The image Madden projected also might have diminished somewhat the lawless reputation of the Bluegrass.

Chapter 7 concludes this study by demonstrating how the rising popularity of the plantation myth created a Southern identity for the Bluegrass; this new identity elevated Kentucky horse country into a place that America’s wealthy desired to own. Consequently, the wealthy bought Kentucky farms, and the industry became centered in the Bluegrass. Madden, Murphy, and others had laid the building blocks; the plantation myth corralled the free-floating images these men had evoked into a nostalgic notion of the antebellum South that white Americans now were eager to embrace. Wealthy capitalists began purchasing Bluegrass horse farms, bringing into the region the big money that enabled the industry to grow. The plantation myth caused these capitalists to overlook and ignore the ongoing violence and lawlessness that continued in the region. It also dashed all future possibilities for African American jockeys and horse trainers in the sport. They simply disappeared even though they had once been iconic to Kentucky racing. However, Northeastern turfmen who now were combining with Bluegrass interests to change the identity of the region looked on African Americans with repugnance. In this instance, big money trumped racial possibilities. A lily-white sport emerged even as the Bluegrass regained its centrality to racehorse breeding. The stamp of approval was the Confederate memorial to General John Hunt Morgan erected at the courthouse in Lexington with major help from families in the horse business.

This story is not told in the published histories of the sport. The narratives popular in Thoroughbred racing generally have assumed that Bluegrass Kentucky was the cradle of the American racehorse and always has been, and always will be, central to the horse racing industry. Not told was the power struggle over where the locus of horse breeding was to be in the postbellum world that engaged Kentucky with the Northeast. Resentments and rivalries spilled over from Civil War battlefields onto the racecourse in the postwar turf. The economic future of the Bluegrass lay at risk.

Kentucky’s horsemen spent a generation attempting to swing the business back their way. When they stumbled on the winning formula, they unexpectedly found willing partners among those outside capitalists who had ignored them in the past. A nationwide need among white Americans for nostalgia, working in tandem with a rising racism throughout the United States, solidified into plantation imagery as the balm to soothe the nation’s soul. The imagery settled on Bluegrass Kentucky, and only then did the horse business in the commonwealth begin to attract the big money needed to grow and support the infrastructure for an equine and tourism industry.

The Kentucky colonel, the columned mansion, and the imagined construct of Bluegrass horse country as representing the Old South cannot be underestimated in securing the Thoroughbred industry its locus in the commonwealth. What follows is the story of how the Bluegrass became Southern.