The Struggle for Independence

For a century and a half, between the defeat of Nawab Siraj-ud-Daula by Clive in 1757 and Curzon’s partition of Bengal in 1905, Muslims played little part in the life of Calcutta. There was no noteworthy Muslim businessman like Dwarkanath Tagore, no Muslim writer like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, and no Muslim religious and social reformer like Swami Vivekananda in nineteenth-century Calcutta. But after the 1905 partition, Muslims began to assert themselves, politically at least. By the time of independence, in the 1940s, Hindu-Muslim hostility was in danger of tearing the city apart.

According to the census of 1872, nearly half of the total population of Bengal was Muslim. They were mainly peasants living in the Gangetic plain of East Bengal (now Bangladesh); very few were landlords and moneylenders. In Calcutta itself, Muslims were in a distinct minority, not more than perhaps 20 per cent. Of these the majority were day labourers - cooks, coachmen and stable boys - in European households, while others were tailors, boatmen, poultry and beef butchers, tobacco and perfume sellers, lascars (sailors), bookbinders and carpenters. Very few held government jobs or professional occupations; indeed, literacy levels were much lower among Muslims than among Hindus. The proportion of Muslims in government service rose from 4.4 per cent in 1871 to 10.3 per cent in 1901 while for Hindus the figures were 32.2 per cent rising to 56.1 per cent during the same period. Most Muslims had come to the city leaving behind their families in rural East Bengal. They congregated in the Zakaria Street, Mechuabazar and Park Circus areas between the White and the Black Town, which Nirad C. Chaudhuri named the “Muhammadan belt”. In his autobiography he observed:

One of the typical sights of these quarters were the butcher’s shops with beef hanging from iron hooks in huge carcasses, very much bigger than the goat carcasses to whose size we the Bengalis were more used. These wayside stalls were redolent of lard, and were frequented by pariah or mongrel dogs of far stronger build and fiercer than the dogs of the Hindu parts of the city.

Chaudhuri also noted - and here his experience was typical of educated Calcutta Hindus - that during the three decades he lived in Calcutta (from 1910 to 1942), Hindus and Muslims lived separately:

I hardly met any Muslims and became intimate with none... I found an arrogant contempt for the Muslims and a deep-seated hostility towards them, which could have been produced only by a complete insulation of the two communities and absence of personal relations between their members. This inhuman antagonism could not exist in East Bengal, where, owing to the number of the Muslims and also to the fact that they were Bengali-speaking, the economic and social life of the two communities was interwoven.

Religious Divides

It was the 1905 partition that made the split between the two communities unbridgeable. Hindus were generally against the partition, Muslims generally in favour because they were in a majority in East Bengal. From 1906, under the guidance of the nawab of Dacca (Dhaka), Salimullah, Bengal’s Muslim population began to organize itself politically and seek separate representation from the Hindus in the councils of the British Raj. This growth of Muslim solidarity in Bengal had a significant impact upon the rest of India. At one level, it consisted of an intensified devotion to Islam and its prayers, rituals and festivals, but at another level, the faithful were actively encouraged to interfere with Hindu practices by, say, touching a sacred water pot, taking water from a Brahmin’s well or defiling the image of a Hindu deity. Sporadic incidents of this kind gradually increased in number and violence, though they did not threaten the overall political stability of Bengal until the 1940s. The British did little to discourage communal friction, which served the purposes of “divide and rule”, and they even fanned the sparks.

Spiritual Visitors and Secret Societies

Strangely enough, as Bengal and India became more politicized, the country struck many foreigners as increasingly spiritual. After Vivekananda’s 1893 success at the World’s Parliament of Religions in Chicago, India began to be seen by more than merely scholars and philosophers as the home of a unique and lofty idealism based on ancient Hindu wisdom, not as a mere British colony. Foreigners started to arrive in search of enlightenment.

Among the early ones was an Irishwoman, Margaret Noble (1867-1911), who heard Vivekananda speak in Europe and became his disciple. In March 1898, he introduced her to Bengali society at an inaugural meeting of the Ramakrishna Order in the Star Theatre. She spoke of the spread of Indian spirituality in Britain and won the hearts of the audience. Rabindranath Tagore dubbed her Lokmata, meaning Mother of the People, though he would always dislike her dogmatism. She herself took the name Sister Nivedita (the Dedicated), dressed herself in a white robe with a string of rudraksha beads (the rosary of the Indian sadhu) around her neck, and soon became both a ferocious champion of Hinduism and a friend of the nascent Bengali political revolutionaries, even corresponding with the Russian anarchist Kropotkin. Although it was religion that apparently first attracted Noble to India, Indian nationalism quickly got a grip on her emotions.

A second visitor was the Japanese art critic and historian Okakura Kakuzo (1862-1913), who in the late nineteenth century helped to rescue Japanese traditional art from the onslaught of western painting. Speaking in 1902, Okakura chided a well-attended Bengali gathering at the Indian Association Hall: “You are such a highly cultivated race. Why do you let a handful of Englishmen tread you down? Do everything you can to achieve freedom, openly and secretly. Japan will assist you.” On another occasion he proclaimed: “Political assassinations and secret societies are the chief weapons of a powerless and disarmed people, who seek their emancipation from political ills.” Coming from the scion of a Japanese samurai family, such advice influenced Bengal’s revolutionaries. But when Okakura tried to motivate Rabindranath Tagore’s nephew with a violent description of the bloody decapitated head of his uncle who had sacrificed himself in the noble cause of Japanese patriotism, he got only a lukewarm response.

Secret societies had existed among educated Bengalis, especially students, since the 1870s, after the fashion of Italian revolutionaries like Carbonari and Mazzini. One of Rabindranath’s elder brothers, Jyotirindranath Tagore, was in charge of such a society. The adult Rabindranath recalled its atmosphere with gentle mockery in My Reminiscences:

It held its sittings in a tumble-down building in an obscure Calcutta lane. The proceedings were shrouded in mystery. This was its only claim to inspire awe, for there was nothing in our deliberations or doings of which government or people need have been afraid. The rest of our family had no idea where we spent our afternoons. Our front door would be locked, the meeting room in darkness, the watchword a Vedic mantra, our talk in whispers. These alone provided us with enough thrills, and we wanted nothing more. Though a mere child I was also a member. We surrounded ourselves with such an atmosphere of hot air that we seemed constantly to be floating aloft on bubbles of speculation. We showed no bashfulness, diffidence or fear; our main object was to bask in the heat of our own ardour.

The fad did not last long. But, a generation or so later, around the end of the century, secret societies were back in fashion, now with an added emphasis on physical culture and military training. A niece of Rabindranath Tagore, Sarala Devi (1872-1945), who admired Miss Noble and was exposed from an early age to the cultural and political movements of the time, founded a society. She had travelled widely, obtained a degree and left marriage until she was well past thirty - unconventional behaviour for a Bengali woman of her time. While in western India, in Maharastra, she had seen a demonstration of fencing with swords and medium-sized wooden poles, known locally as lathis. This is the traditional weapon of the Indian martial arts, but in Bengal a century or so ago, its users were mainly Muslims and lower-class Hindus. (Today, it is Calcutta’s policemen who are often seen brandishing their lathis at the slightest provocation.) Sarala was so impressed that she wanted to introduce lessons in lathi-play to the feeble and passive young men of Bengal. She employed a Muslim circus performer, “Professor” Murtaza, as a teacher, and swiftly the lawn of her Calcutta home in Ballygunj was filled with enthusiastic young men swinging wooden poles. As queen bee of this hive, Sarala inspired her male followers with uncompromising patriotism, which she stimulated with chauvinistic events of her own devising, such as Birastami (Felicitation of the Heroes) and Pratapaditya Utsab - a festival to commemorate a Bengali (Hindu) ruler who fought gallantly against Akbar. Sarala Devi and Sister Nivedita became goddesses for Bengali revolutionaries: apparitions of shakti, the female power, found in Kali and Durga.

The Revolutionaries

Similar societies and clubs began to mushroom all over Calcutta. They were known as akhras, and as already mentioned in relation to College Street and its famous coffee house, these akhras were highly politicized in the early part of the twentieth century. (Today, in roadside akhras the ordinary youth of a locality can be seen working out in a sandpit or claypit, while better-off people go to well-equipped gyms for exercise.) In Nirad C. Chaudhuri’s words:

These [akhras] became a feature of the nationalist agitation of 1905. They were not pure and simple institutions of physical culture, but were, like the Prussian gymnastic clubs organised by the poet Jahn before the war of liberation against Napoleon, institutions for giving training in patriotism, collective discipline, and the ethics of nationalism, with the ultimate object of raising a national army to overthrow British rule.

The most prominent secret society, the Anushilan Samiti (Work-out Association), was led by Jatin Banerjee, nicknamed “Bagha” (Tiger-like) Jatin because he had once single-handedly killed a leopard with a knife. Jatin procured a house at 108 Lower Circular Road (now Acharya Jagadish Chandra Bose Road) and started an akhra on the plot opposite the house. The members concentrated mainly on developing physical strength and stamina through martial arts, horse riding, cycling and wrestling. They also exercised their minds by attending lectures by Margaret Noble and other rousing nationalists on the French Revolution and Mazzini, and reading Hindu scripture, especially the Bhagavad Gita. They had no guns (and only one bicycle and one horse) to begin with, but in due course they started to consider armed robbery as a way of obtaining political funds - despite the definite opposition of Sarala Devi. Meanwhile, throughout this period of training, Banerjee continued to work as a stenographer in the government’s finance department; none of his colleagues knew of his antiimperialist activities.

Banerjee was a disciple of Aurobindo Ghose, also known as Sri Aurobindo (1872-1950), whose statue appears in the Victoria Memorial. In 1903 Aurobindo and his firebrand brother Barin arrived in Calcutta from Baroda (Vadodhara) to observe the organization of the Anushilan Samiti. Unimpressed by its amateurishness, the two brothers took over the leadership, which led to a feud between Barin and Jatin. Although the society more or less dissolved, it would soon regroup under Aurobindo’s influence and become more effective.

The trigger was the proclamation of partition in October 1905. The outburst of feeling in Calcutta went well beyond the earlier stirring speeches and printed appeals. The swadeshi pledge to use only home-produced goods, however poor these might be, led to huge bonfires of heapedup Lancashire cotton and silk and other foreign consumer goods, and the boycott of everything British-made, even matches. Attempts were made to start industries to substitute Indian-made products for foreign ones, and new institutions were set up to provide banking and insurance services with Indian finance. Although considerable credit must be given to these pioneering swadeshi entrepreneurs, they could not achieve much due to lack of leadership, capital and commercial expertise. In most cases their quixotic efforts were thwarted by the nationalist ideology of austerity, by terrorist activities and by British competition. By 1907 the boycott movement had more or less fizzled out, leaving hardly a dent on British financial interests. But it nurtured a spirit of independence which developed into a burning desire to be treated as equals, not subordinates, in business and commerce, both among Bengalis and among Indians in other areas where the movement spread, such as Poona (Pune), Bombay and Madras.

Muslims, however, were generally alienated by the Swadeshi movement. At a meeting in Dhaka, the new post-partition capital of East Bengal and Assam, Muslims headed by Aga Khan III demanded from the British safeguards for their special interests. In December 1906, they formed the All India Muslim League, which pledged loyalty to the British government, supported partition and denounced the nationalist movement.

Aurobindo shrewdly gave Hindu sentiment against partition a strongly religious tinge by writing a political pamphlet (“Bhabani Mandir”) in which he deliberately conflated Mother India - awaiting reinstallation in her rightful temple - with the goddess Bhabani (Kali). His partisan mixing of politics with Hinduism, so much deplored by Tagore at the time, sowed poisonous seeds of discord that would later destroy the relationship between Calcutta’s Hindus and Muslims forever. It was nurtured by Aurobindo and his brother Barin in a weekly Bengali paper, Jugantar (The New Age), which they started in March 1906 without printing their names, and in their writing for another existing English paper, Bande Mataram, founded by Bipin Pal and later edited unofficially by Aurobindo. (The name, Bande Mataram, was chosen to provoke, being that of the nationalist song by Bankim Chandra Chatterjee.) Although both papers were published in Calcutta, they were widely read throughout Bengal, especially among the Hindu young men of East Bengal, who were sturdier, better organized and more devoted to the cause of revolution than the youth of Calcutta. Both papers were prosecuted many times by the government for sedition, and were closed down in 1908.

Apart from writing fiery articles and travelling to meet fellow revolutionaries, Aurobindo and his brother set up a training center in Calcutta. They had access to a deserted ancestral property in the suburb of Maniktola, beyond the circular canal. It consisted of a small one-storied building and some land with fruit trees and a couple of small slimy ponds. Barin enthusiastically set about turning this obscure place into a seminary for martyrs. The cadres followed a strict physical and ideological regime and lived on a frugal vegetarian diet; they also cooked and cleaned. Funds came from a few anonymous backers among the babus of the city. The police had no inkling of the place and its purpose until the backers asked to see some tangible results.

To attract major attention to the cause, the Maniktola akhra decided to kill Sir Andrew Fraser, the lieutenant-governor of Bengal. Ullaskar Dutta, a competent chemist, managed to stockpile dynamite (supplied by a Bengali who owned a mine in north Bengal), while others obtained firearms, probably from the French enclave in nearby Chandernagore. After a couple of abortive attempts to blow up the governor’s train while he was on tour, they succeeded in derailing it in December 1907, but he miraculously escaped injury. Next they targeted Douglas Kingsford, a wellknown judge, with a parcel bomb hidden inside a huge legal tome sent to his Calcutta address, which fortunately for him he did not open. This was followed by a bomb thrown mistakenly at the carriage ahead of the judge’s when he was on his way home from a local bridge club at Muzaffarpur. On this occasion two Englishwomen were killed.

Police suspicion now fell on the Maniktola garden house. A Muslim lathi instructor and trusted associate of some of the revolutionary akhras had turned police informer. But rather than moving immediately to catch the group, plain-clothes policemen tracked their every movement between north Calcutta addresses in College Street, Harrison Road (now Mahatma Gandhi Road) and Grey Street (now Aurobindo Sarani). The police watched them buy chemicals and store them for future use. Sensing the surveillance, the group hurriedly gathered their weapons from various locations and buried them in the grounds of the Maniktola house. Having worked all night, they were about to disperse when armed police suddenly appeared and arrested the thirteen exhausted terrorists; they had no chance to offer resistance. The police dug up the ground again and found three sporting rifles, two double-barreled shotguns, nine revolvers, fourteen boxes of cartridges, and three bombs primed to explode, plus twenty-five pounds of dynamite, large quantities of chemicals, an explosives manual from Paris and coded documents. This enabled the police to raid premises in north Calcutta and make further arrests. The raided premises included the house of Aurobindo, who was living with his wife and sister at 48 Grey Street, where the police were disappointed to find no weapons. The conspirators were all sent to Alipur Jail, where they were kept in nine-by-sixfoot cells with only a tar-coated basket for a latrine.

Meanwhile, a spate of bomb explosions rocked the city. Police found bombs in places like the steps of a Native Christian church in Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy Road. A municipal dust-cart ran over a bomb on a tram track in Grey Street. Several cases of injury from attempted bombmaking were known to Bengalis but hushed up for fear of police reprisals. For weeks everyone in the city could talk of nothing else but bombs. From now on, ordinary Bengalis had brushes with the police, who perceived them as allies of the terrorists. Often Bengali boys looking for fun in a tense city would harass them. My father used to tell me of a seven-year-old schoolmate who frequently teased the police by walking suspiciously with a bump under his shawl, which was actually a mango or guava.

Khudiram Bose, who had undoubtedly thrown the bombs in Muzaffarpur, was hanged. His cool composure when the noose was tied around his neck would inspire many more youths of the city to die for the cause of freedom. The other conspirators were committed for trial; Barin Ghose, by virtue of being born in England, was given the option of trial by jury, which he turned down. A jailbreak was planned. Despite the heavy security, the prisoners managed to smuggle firearms into the jail and organize a quick getaway with the help of sympathizers in the city. But the plot was not put into operation because two of the revolutionaries, Kanai Dutta and Satyen Bose, decided to settle scores with a third, Narendranath Goswami, who had turned against the cause in jail and given evidence against the others. Having murdered the traitor, a month later in September 1908, both Dutta and Bose were sentenced to be hanged. The public response to the announcement was almost totally anti-British. The Bengali press reported how merrily Kanai laughed on hearing his sentence and how bravely he refused the right to an appeal. A European witness of the hanging in November asked Barin Ghose: “How many boys like this do you have?” An hour afterwards, Kanai’s body was handed over to relatives waiting with a flower-strewn bier. As they carried him to the burning ghat, thousands of barefoot mourners joined in. When they passed the nearby temple at Kalighat, although Kanai was from a weaver caste, a Brahmin priest came out and decked the corpse with a garland as a tribute to a hero. Many housewives from respectable families anointed it with sandalwood paste and vermilion powder. Kanai’s hair was shorn and the locks distributed as relics; so were the ashes. As a direct result of such scenes, when Satyen Bose was hanged eleven days later, the authorities compelled his relatives to cremate him within the prison yard.

The day of judgment on the remaining prisoners from the Maniktola group was kept secret for fear of a riot. Around mid-morning on 6 May 1909, five hundred military policemen took up position on the roads and lanes between the jail and the courthouse. The English judge in the case was C. P. Beachcroft. Beachcroft who had been a contemporary of Aurobindo Ghose at Cambridge University in the 1890s, pronounced two death sentences, on Barin Ghose and Ullaskar Dutta. According to the report in The Bengalee - an English newspaper run by a Bengali but certainly no supporter of terrorism - Ullaskar responded to the sentence by singing:

Before the court sat, in fact before the clattering of the hand-cuffs and creaking of boots were stopped, a voice, at once melodious and powerful issued forth from the prisoner’s dock... All the “golmal” [hubbub] in the room - even on the verandah - was at once hushed into perfect silence. Even the European sergeants - to whose ears an Indian tune would not naturally sound very sweet - adopted the posture of attention and began to listen with undivided attention.

The song was by Rabindranath Tagore, one of many that had been sung throughout the city in protest against partition. The Bengalee printed the words - probably the first published translation of a Tagore patriotic song - which showed how Rabindranath eschewed jingoism in favour of adoration of Bengal’s natural beauty and nourishing quality:

Blessed is my birth - for I was born in this land.

Blessed is my birth - for I have loved thee.

I do not know in what garden,

Flowers enrapture so much with perfume;

In what sky rises the moon, smiling such a smile.

...Oh mother, opening my eyes, seeing thy light,

My eyes are regaled;

Keeping my eyes on that light

I shall close my eyes in the end.

The judge then handed down further sentences of life imprisonment in the Andaman Islands. But there was no conclusive evidence against Aurobindo and he was unexpectedly released. His acquittal delighted Bengalis and annoyed the British who criticized the judicial process for letting the ringleader get off scot-free. The judge, however, maintained that “No Englishman worthy of the name will grudge the Indian the ideal of Independence.”

On appeal, after political lobbying both in India and in Britain, the death sentences were repealed. Both prisoners were also sent to the Andamans. Barin was released ten years later but Ullaskar lost his mind as a result of the hard labour in the penal colony. He was sent to an asylum in Madras, later released cured and lived till 1965. Aurobindo left Calcutta and went to French territory, first to nearby Chandernagore and then to Pondicherry in south India. Here he founded a now-famous ashram and became a spiritual leader. His conversion to mysticism had come from his hours of meditation during solitary confinement in Alipur Jail.

I recall being driven past the forbidding perimeter walls of Alipur Jail as a child and listening to one of my uncles - a gentle man but a terrorist sympathizer - telling me all about the young revolutionaries who had once bravely paid the price for our independence. I remember a feeling of something like gratitude. Much later, I came to feel that the lives of these young men certainly exonerated Bengalis from the common charge of having no courage.

Hindu-Muslim Confrontation

If the Swadeshi movement and its violent fringe was largely ineffective against the British, its effect on Hindu-Muslim relations in Bengal was sadly all too influential. By 1907 the goal of swaraj (home rule) had captured the minds of eighty per cent of Bengali Hindus, but had left unmoved all Muslims bar a tiny Calcutta-based group known as the Bengal Mahomedan Association. This group tried in vain to persuade Bengali Muslims to unite with Hindus in the cause of national freedom, while the viceroy Lord Minto appealed to their self-interest and courted them as a counterbalance to the anti-partition movement.

Trouble soon broke out between the two communities in the early months of 1907 in Comilla and Jamalpur in East Bengal, where a nationalist boycott of foreign goods had the effect of forcing poor Muslims to buy swadeshi goods at a higher price than their foreign equivalents. Itinerant mullahs, preaching in village mosques against the nationalists through sermons and pamphlets, heightened the tension. Rumours of communal atrocities in remote villages printed in sectarian newspapers made the situation worse. Aurobindo Ghose, writing in Bande Mataram, called blatantly for confrontation with Muslims: “The Mahomedans may be numerically superior in some districts, but in India as a whole Hindus outnumber the Mahomedans. And is not this an occasion for all India to take up the cause of dishonoured religion?” The fact that the landlords in East Bengal were mainly Hindu, while their tenants were Muslim, contributed further to the discord. All over Bengal, there grew an atmosphere of pervasive mistrust between Hindus and Muslims.

In Calcutta, following Minto’s government reforms introducing Indian members into the legislature, competition between the two communities for official posts was fierce, creating resentment between the educated classes. But the first violent clash arose from a different kind of rivalry, between Muslims and Marwaris.

The Marwaris and Barabazar

The bulk of the Marwari community in Calcutta had come late to the city, chiefly around 1890, from their home state of Rajasthan, escaping its desert and drought conditions, although some arrived even in the 1830s. Traditionally, Marwaris were money-lenders who worked extremely hard, took business risks, and looked after their own, while mostly following Jainism in religion. They soon established a thriving business in moneylending and petty trading in north Calcutta’s Barabazar. They also embellished the showy Jain temple at Badridas Temple Street, designed and built by Rai Bahadur Badridas, a court jeweller, in 1867 and described by Geoffrey Moorhouse as “a shrine of filigree delicacy and sherbet sweetness... with mirror-glass mosaic smothering its interior” - a place well worth visiting.

Nowhere in Calcutta are the sights, sounds and smells of the city more vivid than in the labyrinth of Barabazar. This is where the starving protagonist of Dominique Lapierre’s sentimental bestseller City of Joy (1985) arrives in search of survival and, maybe, a fortune. To reach its alleys full of an amazing collection of goods, you have to dodge all manner of overloaded vehicles, coolies with huge loads precariously balanced on their heads, and thousands of people.

The British established the market on the site of an old bazaar in the late eighteenth century for trading in jute and textiles because the location was close to river transport. With the building of Haora Station in 1854 and Haora Bridge in 1874, Barabazar expanded into the biggest wholesale market in India with a stock ranging “from pins to elephants,” as they say in Bengali. In the sari section alone, the astounding range of designs, textiles and colours runs into thousands. Most of the traders are Marwaris and Punjabis with only a scattering of Bengalis. The main form of currency is hard cash; it is impossible to miss the traders licking their index fingers and counting huge bundles of rupee notes.

Here you may feel choked by the smell of burning fuel, rotten food debris and organic excretions of various kinds. But you will also be assailed by savoury smells wafting from roadside food stalls frying samosas, onion bhajis and delicious omelettes. Around the area of fresh produce, the smell of ripe mango or jack-fruit will overwhelm you, and the heady mixed fragrance of flowers, sandalwood paste and incense from some small shrine nearby will entice you to take a peep.

Sprawling over five square miles and catering for more than a million people every day, Barabazar is a dingy, rackety, overcrowded, daunting and yet oddly orderly place, with each trader owning at least a desk space and a letter box. Larger traders have a private showroom for their wares, while others work with sample goods. Deals are done in a relaxed manner over a cup of tea or a bottle of Thums Up (a highly sweetened cola manufactured by the Coca-Cola company specifically for sweet-toothed Indians). Traditional trading offices exude a social atmosphere, featuring a low-level sitting area (known as a gaddi) scattered with bolsters. Most traders have been here for over decades and are resourceful types. Although computers have arrived, it is mobile phones that are the most popular technology; mobiles allow the traders to keep in continuous contact with Lyons Range in central Calcutta, the city’s stock exchange.

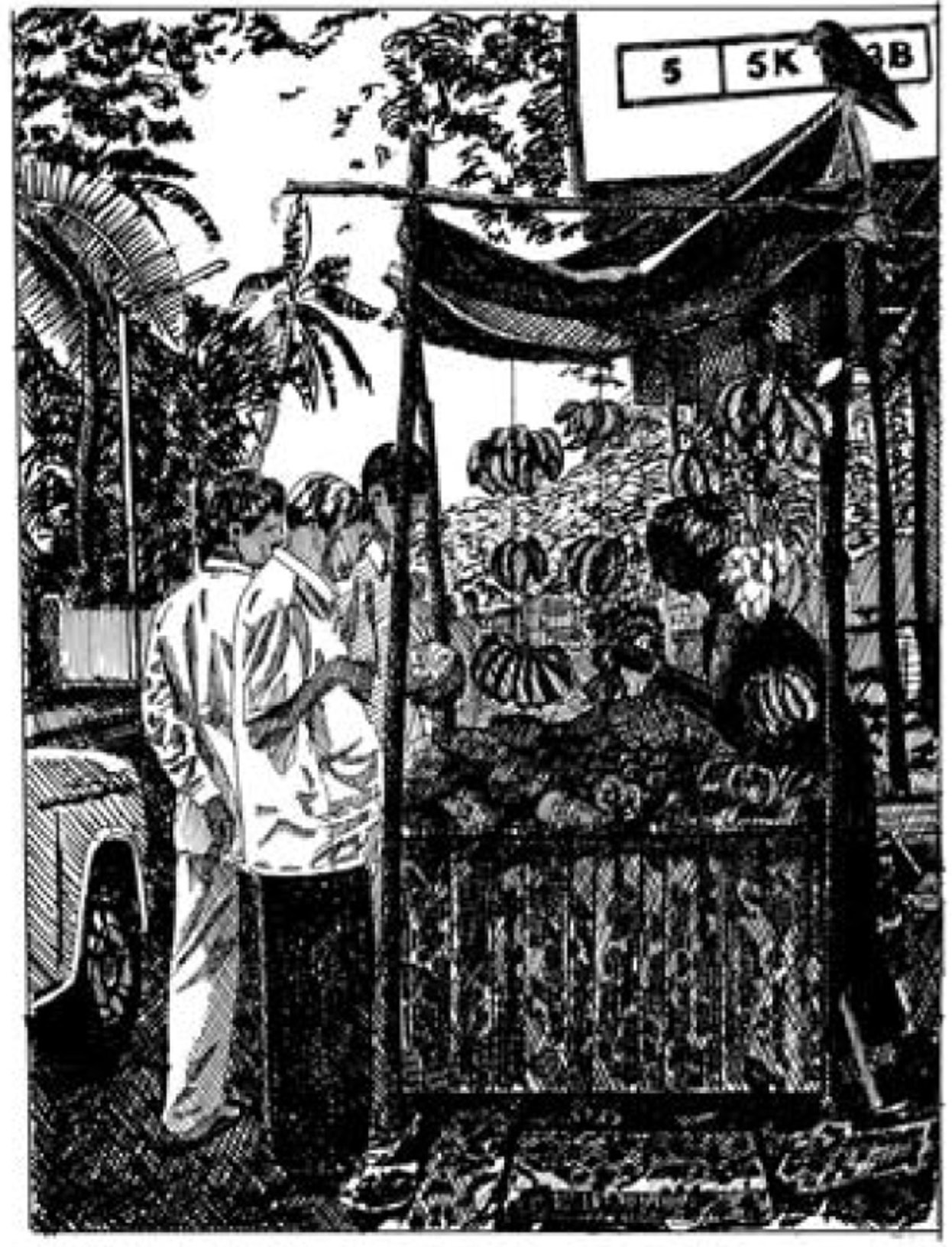

Pavement peddler in Barabazar

The big business of the city is not done in Barabazar. It occurs in the network of streets around the Writers’ Building, lined with trading offices and company headquarters. During the day the area heaves with clerks, male and female, who weave their way between the vehicles and the street merchants. The Birlas, an all-India Marwari-run family company, are the biggest players, owning a diversified business empire that ranges from agricultural tools to shipping and automobiles. The Birlas are often compared to American dynasties like the Fords and the Rockefellers, both for their business acumen, their wider influence in society and their somewhat dubious early history.

The state government is currently encouraging trade and commerce to spread out from this hectic commercial hub around BBD Bag (Dalhousie Square) to other areas of the city like Park Street and Salt Lake (see p.179). The modern district of Salt Lake now hosts several hi-tech industries and is home to a thriving software export business. The “hottest” spot for business is now fittingly Camac Street, named after William Camac, a senior East India Company merchant in the days of Cornwallis and Wellesley (no name change here yet!). Camac Street runs from Park Street to Lower Circular Road and has been the haunt of the rich and classy for over two hundred years or so. However, the rising cost of maintenance, disputes over inheritance and ever-escalating tax bills are forcing the present owners of crumbling grand houses to sell up to property developers who are building multi-story complexes that they can rent out to business houses. The government’s commerce department is here and more departments from the Writers’ Building are due to transfer to the area. There are also expensive shopping arcades, restaurants, cafés and bars where Calcuttans in designer clothing like to hang out.

Communal Riots and Non-cooperation

During the economic turmoil of the First World War, Marwaris made a killing out of speculative buying and selling, not to speak of adulteration of foodstuffs such as ghee (clarified butter) - while at the same time attempting to outlaw the Muslim slaughter of cows for beef. It was not long before they were detested by both Hindus and Muslims for making money unscrupulously while living in a world of their own in large houses protected by armed guards from Rajasthan. When, soon after it was founded in 1911, the Calcutta Improvement Trust began to clear the slums inhabited by poor Muslims, the land was sold to wealthy Marwaris who built ostentatious mansions on roads like Zakaria Street and Chittaranjan Avenue (now rented out because their original inhabitants have moved to more sought-after addresses in Park Street, Alipur and Khidirpur). The dislodged Muslim tenants were duly aggrieved.

Calcutta’s Muslims were already disappointed by the rescinding of the partition and the reunification of Bengal in 1911. Then, during the First World War, there was a sharp increase in the price of essentials like rice, wheat, salt, cooking oil and clothes because of speculative hoarding by Marwaris - which hit poor Muslims in Calcutta hardest and further fuelled their resentment. By the second half of 1918, the scene was set for the first of several major communal riots in Calcutta.

By then a fair number of wealthy Muslims - exiled princes (like the descendants of the nawab of Oudh and his entourage settled in Metiaburz, a southwestern suburb inhabited now mainly by Muslim tailors), landlords, and merchants - were living in the city. At the same time, as we know, the labour force contained a large Muslim element, which was increasing with the industrial development of Calcutta. The two groups would meet regularly at the Nakhoda Mosque.

The Muslim elite provided the oppressed poor with the leadership required to rebel against their conditions. Their growing disaffection was easily manipulated when Turkey joined the First World War against the Allies. Although the vast majority of Calcutta Muslims had no understanding of international politics, the pillars of their community presented the war against Turkey as a war on Islam. Weekly sermons at the Nakhoda Mosque drove the message home and gradually the congregation came to see a connection between their personal grievances and the alleged international conspiracy to undermine their faith. They were ready for a jihad, a holy war, not only against the Marwaris but also against the British.

For three days, from 9-11 September 1918, the Muslim mob damaged or destroyed civic property, the public transport system and some Marwari houses including the Jain temple, without touching any of the Hindu temples and shrines in the area. Marwari-owned shops were ransacked and set on fire. Several traders were stabbed and killed. In the final count, fortythree civilians died - thirty-six of them Muslims - and four hundred people were arrested. The stock exchange was closed because of the absence of the Marwaris; there was a food shortage, and north Calcutta’s streets had to be cleared of debris before the city could function again. But Bengali Hindus were unharmed and not a single Hindu among the police force was hurt. Even so, the riot was the start of the labour unrest that has dogged the city ever since. Most of the mill workers in the industrial suburb of Garden Reach were upcountry Muslims, who were politicized by agitators calling on them to attend a rally instead of going to work. When they went on strike, they found themselves pitted against their European employers, with serious consequences.

The first big communal riot severely disrupted normal life, especially in north Calcutta. Law and order was gradually restored - only to be disrupted again by an unprecedented demonstration of temporary solidarity between Hindus and Muslims, as Gandhi launched his movement of civil disobedience. From 1920 onwards, until independence and after, Calcutta would be in an almost constant state of tension.

The repressive legislation that had provoked the Amritsar massacre in April 1919 was known as the Rowlatt Act; it became law in late 1918. Not long after, Gandhi issued a rallying call against the measures in the act, and this received a response from Calcutta’s Hindu population, led by Surendranath Banerjee, Chittaranjan Das and Subhas Chandra Bose. In 1919 Hindus and Muslims took to the streets shouting “Bande Mataram!” and “Ali Ali!” in unison, under the unlikely joint banner of Gandhi’s satyagraha (truth force) and the Muslim Khilafat (Caliphate) Movement, which was agitating to retain the sultan of Turkey, defeated in the war, as the caliph or religious head of the Islamic world. A joint meeting of Hindus and Muslims was held inside the Nakhoda Mosque in the same year, chaired by Gandhi’s son Hiralal. Soon, educated Bengalis threw themselves into a flurry of political activity, raising funds, holding meetings, preaching temperance, and of course spinning and weaving. The cult of the spinning wheel, known as the charka, was Gandhi’s pet project, and it caught on even in Calcutta, despite the opposition of Tagore, who rightly regarded it as an ineffective activity for nation building. As he wrote scathingly to a Bengali friend in 1929: “The charka does not require anyone to think: one simply turns the wheel of the antiquated invention endlessly, using the minimum of judgement and stamina. In a more industrious and vital country than ours such a proposition would have no chance of acceptance - but in this country anything more strenuous would be rejected.” But Tagore was here in a small minority; virtually every household in Calcutta acquired at least one charka which family members would take turns to spin solemnly each day and then send the threads to the weavers. The act of spinning generated a warm patriotic glow in the new era of mass politics.

The climax of this first phase of non-cooperation came with a nationwide general strike on 17 November 1921 against the prince of Wales’ visit to India. In response to Gandhi’s call, Calcutta that day looked like a deserted city with empty streets, closed shops and offices, and no switching on of electric lights at night. It was seen as a national day of mourning, according to The Statesman’s editorial on the following day.

But as the newly politicized masses slowly became addicted to the excitement of patriotic activity and relative anarchy on the streets, communal discord simmered below the apparently harmonious surface of nationalist politics. Inflammatory political leaflets continued to circulate underground in both communities. Hindus felt that the majority community had a right to impose itself on the minority communities; mullahs continued to incite anti-Hindu animosity at weekly sermons in the mosques.

On 2 April 1926, a group of Hindus belonging to the Arya Samaj led a procession singing devotional music which passed noisily outside a mosque in north Calcutta while the Muslims were engaged in prayer. This provoked the city’s second major communal riot. Marwari houses and warehouses were again vandalized and looted, and these acts of violence were followed by attacks on Muslim property and persons. The violence was supported on the Muslim side by the deputy mayor of Calcutta, H. S. Suhrawardy, and on the Hindu side by the terrorist akhras. Although statements were issued by both communities ostensibly condemning the incidents, street brawls and stabbings now became regular occurrences in certain parts of the city.

A new group of troublemakers, known as goondas, embarked on a savage spree of damage and destruction, including places of worship. Such hoodlums were originally commandos in the service of the East India Company, who were later retained by wealthy landlords for protection and dirty work. Now they were hired by political factions to extort money from supporters and beat up political opponents. After the 1918 riot, Marwari merchants brought in goondas from neighbouring Bihar, uneducated but strong and macho young men willing to do almost anything for money and power. They became such a nuisance to ordinary citizens that the government passed a Goonda Act in 1923 to control them. After independence, ordinary Calcuttans suffered increasingly under their tyranny; people spoke casually of “Congress goondas”, “Marxist goondas” and other types of goonda. Today, they form the majority population in Calcutta’s prisons with criminal records ranging from pilfering to contract murder.

There was an important difference between the riot in 1926 and that in 1918: the communal polarization had become much sharper. Hindus were organized in the second riot, driving out Muslim marauders with bricks hurled from roof tops; while Muslim pockets near the Nakhoda Mosque and in Mechuabazar and Kalabagan became no-go areas for Hindus. Nevertheless, there were instances of mutual cooperation in quelling the violence. Many Muslims protected their Hindu neighbours, and vice versa.

But in general, from the time of the 1926 riot onwards, Calcutta became a city of processions and demonstrations with an increasingly chaotic work culture. At the feeblest excuse, half a dozen people would begin a march with a makeshift banner and shout slogans; and many more would quickly join in, disrupting traffic and becoming rowdy. The first target would usually be a tramcar. The bewildered passengers would be forced off, and the car would be set alight. The fire brigade would then arrive, almost always in time to stop the conflagration getting out of hand. In due course, the tramways authority no longer bothered to repaint and repair the vehicles, and Calcutta’s once-gleaming and elegant trams (as I remember them even as late as the 1960s) came to look like battered and burnt cooking pans. Perhaps the communist government that has ruled the city since the late 1960s decided to indulge this culture of protest as being a safer outlet for people’s frustrations than the armed revolution of the early 1970s. Anyway, Calcuttans have grown to tolerate such civic hazards - just as they must tolerate the floods during the monsoon that annually turn parts of the city, such as Jorasanko, into a shabby Venice with half-drowned rickshaws plying the streets instead of gondolas.

The Rise of Subhas Chandra Bose

In 1927, a Trade Union Act came into force enabling employees to form their own union. As it lacked effective provisions against irresponsible strikes and picketing, Calcutta’s labour force grew steadily more militant. Dock and transport workers, railroad workers, mill hands, garbage collectors, sweepers - all began to use their clout to paralyze economic and civic life. Agitators from both the political right and left infiltrated the unions; by 1930 the communists had established a firm hold, working at the grass-roots and organizing popular campaigns through small meetings and simply written handouts.

This atmosphere provided fertile ground for a return of revolutionary terrorism, which had been relatively dormant during the 1920s. In December 1930, three terrorists entered the Writers’ Building - the administrative centre of the Government of Bengal - and managed to obtain an interview with Colonel Simpson, the inspector-general of prisons. Having shot him dead, two of the assassins, Badal Gupta and Dinesh Chandra Gupta, took cyanide and escaped capture; the third, Binay Krishna Basu, survived, and was tried and hanged for murder the following year. All three were young men (Badal was only 18) from respectable families, following the earlier tradition of educated terrorists at the time of the 1905 partition. Their memories were preserved when, after independence, Dalhousie Square, the north side of which is occupied by the Writers’ Building, was renamed Binay-Badal-Dinesh Bag. This is usually shortened to BBD Bag, using the English initials of the martyrs - although there exists another version based on their Bengali initials pronounced Bibadi Bag, which means roughly “garden in dispute”!

There were also women revolutionaries from respectable families. Calcutta’s women had played a major role in the marches and picketing carried out by the non-cooperation movement, and had received the same violent treatment as men, along with prison sentences. By emerging from their homes and joining politics in large numbers, they gave a distinctive colouring to Bengal’s and India’s freedom movement. Better than the men at social organization, the women founded primary schools and maternity and child-welfare centres in Calcutta that would continue to benefit the city after independence, though the city women made little contact with the impoverished women of the villages, especially the Muslims who continued to observe purdah. Of the relatively few Calcutta women who went further than civil disobedience and actually joined the revolutionaries, the most famous was Bina Das, who fired a shot at the governor of Bengal during the 1932 convocation of Calcutta University. (She survived, and lived until 1986.)

Massive police surveillance and military operations crushed the revolutionary activities in Calcutta and various parts of Bengal during 1931-33; a whole battalion of British infantry and six battalions of Indian infantry - all Gurkha regiments (as used at Amritsar in 1919) - operated from two brigade headquarters in Bengal at this time. Much later, during the cold war, British intelligence officers who had experience of counterinsurgency work in Bengal, would be regarded as particularly valuable assets by the Special Branch and MI5 - such was the reputation of Bengali terrorism in the 1930s. The repression continued under the governorship of Sir John Anderson (later Viscount Waverley) from 1932-33. So severe was it that the terrorists of Bengal would play no part in the ending of British rule in the 1940s.

Subhas Chandra Bose (1897-1945), the undoubted political star of Bengal at this time, was a regular inmate of British prisons. His incarcerations helped to ensure his popularity in Calcutta, where he became known as Netaji (Revered Leader). Even Tagore offered his support, dubbing Bose Desanayak (Leader of the Nation) and asking factionridden Bengalis to rally round him in a speech given in 1939: “More than anything else Bengal needs today to emulate the powerful force of your determination and your self-reliant courage.” In vain: Bose failed to unite his people, fell out with Nehru and Gandhi (and even Tagore), and during the Second World War misguidedly turned to the fascists in Germany and Japan for help in fighting the British Raj. (He founded the Indian National Army with Japanese support, and fought the Allies in Burma.) As Nirad C. Chaudhuri, who in the 1930s was secretary to Bose’s elder brother, the Calcutta politician Sarat Bose, perceptively commented: “Since Subhas Bose was challenging what might be called the nationalist Establishment in India, he needed a party all the more. Yet he never had one. His following was always floating, shifting from year to year to different factions.”

Yet no other Indian political leader so captivated Bengal, with its revolutionary romanticism, as Subhas Chandra Bose. His patriotic ardour and explicit hatred for the British are legendary. The letter he wrote in 1919 as a student at Cambridge University to a Bengali friend is often quoted approvingly in Calcutta: “Nothing makes me happier than to be served by the whites and to watch them clean my shoes.” Political parties of all types - the Congress, the Marxists, and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) - have each claimed Bose as a political godfather. Most major Indian cities have streets named after him, while the central government in Delhi, in addition to allocating generous funding for research into Bose’s life, issued a commemorative two-rupee coin on his birth centenary in 1997. In Calcutta, despite Bose’s fascist connections, the Left Front government named the city’s new international airport not after Rabindranath Tagore, Bengal’s greatest son, but after Subhas Chandra Bose - Bengal’s Netaji.

The Netaji Bhavan, his ancestral home on Lala Lajpat Road (formerly Elgin Road) in Bhabanipur in south Calcutta, is now a museum celebrating his life and achievements through photographs, statues and other approved memorabilia. Beneath the porch is a replica of the Singapore memorial to the martyrs of his Indian National Army blown up by the British in 1945. Outside in the yard is Bose’s get-away car, in which he escaped from house arrest in January 1941, dressed as a Muslim upcountry gentleman. Having reached Delhi, he boarded the Frontier Mail to Peshawar, and from there, disguised as a mute Pathan pilgrim, went by mule across the Afghan border and was eventually smuggled to Nazi Germany, from where he went by German submarine to Japan.

Subhas Chandra Bose

Many Bengalis still revel in the story of his great adventure; for them Bose retains the charisma of a Che Guevara, untarnished by his later career. In fact for several decades, until the 1980s, many people in Calcutta refused to accept the official Indian account of Netaji’s death in a mysterious plane crash in Taiwan at the end of the Second World War, and insisted that he was still alive and would return to India. In Calcutta’s addas they still like to speculate about how Bose would have solved the IndoPakistan and Indo-China conflicts which have dogged the country since independence. Around 1970, I was in the College Street coffee house when a group got into a violent disagreement about the precise nature of Bose’s relationship with Hitler. In 2001, while chatting with some young men gathered near my family house in north Calcutta on Independence Day (15 August), I found that most of them believed their revered Netaji had marched on Delhi with his army in 1947 and driven the British out of India. When I told them Netaji had died in 1945, that he drank alcohol and ate beef, and had a daughter by an Austrian women named Emilie Schenkel, they laughed me away in disbelief.

Scepticism about his wartime role apart, Bose had genuine concern for Calcutta. He worked tirelessly for civic improvement as chief executive of the Calcutta Corporation from 1923 until he left India in 1934. He was elected as mayor in 1930, and put forward a programme for education, medical care for the poor, and transportation, and visited other cities of India and Europe to seek out models for improving Calcutta. But as Nirad C. Chaudhuri has observed, instead of doing something concrete and far reaching for his beloved city, he “became more and more a prisoner in the hands of the hard-boiled and worldly middle-class of Calcutta, to whom civic welfare meant the welfare of their class.”

Bose’s moon-faced, bespectacled image in army uniform can always be spotted on Calcutta’s walls in drawings and posters. He is often shown as a mythical hero riding ahead on a horse like an avatar of Kalki, the final incarnation of Vishnu, saviour of the world, or as Shivaji, the Maratha leader who successfully resisted the armies of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in the seventeenth century. For Bose loved uniforms. His own was designed and made, ironically enough, by a firm of British tailors, Harmans. He gave himself the rank of General Officer Commanding and set up a volunteer corps with a women’s contingent dressed in trousers. Gandhi caused much offence to Bengalis when he said that Bose’s volunteer corps reminded him of the Bertram Mills Circus.

Three times a year in Calcutta - on 23 January, Bose’s birthday, on 26 January, Republic Day, and on Independence Day in August - countless small memorial shrines with images of Bose and bunting in the colors of the national flag spring up in the streets of the city. The potters of Kumortuli keep a permanent stock of clay busts of Bose. Early in the morning on these days, youths gather locally to sing the marching song of the Indian National Army, Kadam Kadam (“Forward Forward”). The tune is uncannily similar to the English nursery song about Noah’s ark, The Animals Went In Two By Two.

The cult of Bose, for that is what it certainly is, is partly the result of his memorable anti-British sound bites, and partly because (unusually for a Bengali) he had some prowess as a military leader. He and his army were certainly courageous, even if he led them to total disaster in the jungles of Burma. He did his best to undermine the British view of Bengalis as effete babus by training his followers in disciplined activities, though with limited success; and in the Indian National Army he united all communities, including Hindus and Muslims, with greater success. But more important than anything else, the cult has flourished because of an absence of moral leadership in today’s India - no Gandhi or Nehru or Tagore to set an example - which has created a psychological necessity to idealize Netaji Subhas.

The Bengal Famine

During the war, in 1943-44, Bengal was struck by a terrible famine that claimed somewhere between three and five million lives through starvation and epidemics. Generally regarded as man-made, the famine has long been the subject of much discussion, analysis and some controversy over the particular contributions of the Allied war effort, hoarding and profiteering in causing it. Although the worst effects were to be found in the villages, the famine had a major impact on Calcutta.

H. S. Suhrawardy was the food minister of the provincial government throughout the famine. In May 1943, just as it was beginning, he gave a public assurance that there would be no shortage of food in Bengal. Although there were rumours about lack of rice supplies due to hoarding and profiteering, the Bengal Government - which was by then almost entirely Indianized - did nothing to prepare Calcutta for the invasion to come. Villagers walked into the city in search of scraps, some dying by the wayside, the rest arriving half-dead. There they dragged their emaciated bodies from door to door begging for phyan, rice water, the starchy liquid left after boiling rice that is usually poured away or used for stiffening clothes.

My mother and my aunts used to keep phyan for these beggars. If any of it slopped over while being poured into their battered containers, they would immediately lick it up from the floor like a cat. Starvation had weakened their digestion so much that if they were given any food more indigestible than phyan, they would vomit. My father, who taught anatomical dissection at R. G. Kar Medical College, used some of the unidentified corpses of famine victims. He told me they had eaten dogs, rats and snails and garbage scrounged from domestic refuse. Malnourished babies were dumped at the doorsteps of Calcutta families and children were sold in exchange for food. A reporter spotted the body of a child half-eaten by a dog in Cornwallis Street (now Bidhan Sarani), one of the city’s main thoroughfares. Calcuttans began to go to work stepping over an occasional corpse. By September 1943, there were clusters of dead bodies in the streets, mostly of women and children, but still the government did not officially admit to the desperate situation. Only in October was the Bengal Destitute Persons Ordinance passed declaring Calcutta to be famine stricken, and the police were instructed to clear the corpses from the streets and issue food to the starving.

Nevertheless, there was a concerted effort to suppress the exact statistics of fatalities from starvation and related diseases, such as cholera, dysentery and typhoid. At the height of the famine, around 11,000 people were dying every week in Calcutta. Jackals and vultures had a field day. The burning ghats of Nimtola in the north and Keoratola in the south filled the city with the smell of charred human flesh. One of the Doms - who organize cremations - told my uncle wryly that at least starved and dehydrated bodies saved on wood because they burned better and quicker than well-fed ones.

Otherwise, the harsh truth is that middle-class Calcutta life carried on pretty much as normal. There was no food shortage for government workers and professionals. Although many of the starving lay in front of shops and warehouses stuffed with food - there was even a bumper crop of wheat in the spring of 1944 - they never raided any Calcutta shops. There was none of the disruption caused by communal riots. The famine victims were more or less resigned to their fate: they were simple village folk, confused by their unprecedented predicament. Thus most better-off Calcuttans failed to grasp the severity of the famine - or at any rate closed their eyes to it.

They could not close their ears, though. The unforgettable whining of the beggars addressed to the ladies of a house, “Phyan dao Ma” (Give us rice water, Mother), was heard all over the city, as the novelist Bhabani Bhattacharya remembered: “You heard it day in and day out, every hour and every minute, at your own house door and at your neighbours’, till the surfeit of the cry stunned the pain and pity it had first started, till it pierced no longer, and was no more hurtful than the death-rattle of a stricken animal. You hated the hideous monotony of it.” Although The Statesman published some distressing photographs of the dead and dying, they made little impact in the city. Of course, there was no television. The desperate rural beggars were treated more as a civic nuisance than as pathetic victims; they became a race apart. “There was stink in the air but not much anger,” recalled Mrinal Sen, the film director. Satyajit Ray, then starting out as a commercial artist, looked back and confessed that he had been “a little callous” about the famine: “one just got used to it, and there was nobody doing anything about it. It was too vast a problem for anyone to tackle.” A quarter of a century after the famine, both film directors made sensitive, and to some extent conscience-stricken films about the period: Baishey Sravan by Sen, and Ashani Sanket (Distant Thunder) by Ray. The economist Amartya Sen, then a boy, witnessed this suffering with bewilderment, which spurred him as an adult to study famines. He recalled, “It is hard to forget the sight of thousands of shrivelled people - begging feebly, suffering atrociously, and dying quietly.”

The Great Killing

In the run-up to independence in 1947, Calcutta was shaken by an intensification of communal violence. Never before had the city experienced such a tremendous outburst of primordial hatred between Hindus and Muslims. It was, of course, the wrangle between the Congress, led by Nehru, and the Muslim League, led by Mohammed Ali Jinnah, about how to divide India, that provoked the fury. Jinnah gave a call to all Muslims to suspend business on 16 August 1946. By then, Bengal was being ruled by a Muslim League-dominated ministry, headed by the famine-denier Suhrawardy. He decided to declare 16 August a public holiday despite Congress opposition.

The Muslim League called a mass meeting at the Ochterlony Monument on the Maidan - now known as the Sahid Minar, the martyrs’ minaret, at which Muslims still gather for prayer meetings. Streams of people converged on the monument. In the heat and humidity of a monsoon afternoon, they heard inflammatory speeches including one by Suhrawardy and became increasingly volatile.

For weeks they had been sharpening their knives and daggers for a jihad. Now, at the end of the meeting, they were uncontrollable and let loose their animosity on anything that came in their way, looting, stabbing, and burning. Slum dwellers in Kalabagan and Rajabazar were burnt alive or hacked to death with axes and swords. By evening a curfew had to be imposed, after which violators would be shot on sight. The night echoed with chants of “Allah ho Akbar” and “Bande Mataram”.

The next morning a train, the 36 Down Parcel Express, was forcibly stopped just outside the city and its crew butchered. Families now took to sheltering in a single house, leaving looters to ransack their other houses. The mob had gone berserk. The area most affected was bounded on the north by Vivekananda Road, on the south by Bowbazar Street, on the east by Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy Road and on the west by Strand Road. A downstairs room in my ancestral home in north Calcutta facing the street was let to a Muslim shawl mender. When the rioters broke into it, my uncles helped him to escape into our house through a service door. He shaved his beard and wore a dhoti instead of a lungi and hid in our house for some days, lucky to be alive. The rioters may well have guessed where he was but they left us alone. In those parts of the city like ours where Hindus and Muslims had lived together for a long time, there were many instances of trust and loyalty between neighbours. Even the house of the Tagores was attacked on suspicion of sheltering local Muslims. But mostly it was a story of senseless slaughter. Many Bengali short stories capture those terrible days. Perhaps the best one is “Adab” (“Farewell”) by Samaresh Basu, written in 1946. Two terrified strangers, ordinary men, confront each other in a deserted nighttime street while sheltering on either side of a large rubbish bin. Rioting can be heard in the near-distance. Are the two men Hindu or Muslim? They do not know each other’s identity and have no easy way of telling. Naturally, they suspect the worst. Basu portrays their wild oscillation between fear and fellow feeling with emotional power and concision, as they finally reveal themselves to be a Hindu and a Muslim. In the end they decide to help each other, but one of them, the Muslim boatman, is shot by a British policeman while trying to escape across the river to his wife and family.

In the event it took a week for the police and the army to restore some order. The Muslim League and the Congress tried to impose a catchy slogan “Hindu Muslim ek ho” (Hindu-Muslim unite) - but it was futile. The goondas were in charge, manipulating a combination of jihad and the cult of Kali. Hideous violence continued for three more days.

The Statesman blamed Suhrawardy’s ministry for the carnage - with much justification. On 20 August, it commented:

Maintenance of law and order is any Ministry’s prime obligation... But instead of fulfilling this, it undeniably, by confused act of omission and provocation, contributed rather than otherwise to the horrible events which have occurred... It has fallen down shamefully in what should be the main task of any Administration worth the name. The bloody shambles to which this country’s largest city has been reduced is an abounding disgrace...

It added: “This is not a riot. It needs a word found in mediaeval history, a fury. Yet, ‘fury’ sounds spontaneous, and there must have been some deliberation and organisation to set fury on its way.”

There was a massive exodus from the city. More than 100,000 people left by road and rail that week. About the same number lost their homes. So many people went missing that The Statesman published a poignant notice on 21 August: “Information would be welcome about those Indian members of The Statesman staff in Calcutta who have not been in the office since 16 August. Would those whom the recent events still preclude from returning from duty please send news of themselves?” Meanwhile, the Hugli River was awash with rotting and mutilated bodies, and the city’s sewers were blocked by bloated corpses.

Exactly how many people were killed during those ten days in August 1946 is difficult to ascertain. By 27 August 3,468 bodies had been identified; the total number of dead may well have been twice that figure. Small-scale butchery continued in Calcutta for a year. When Gandhi visited the city in mid-August 1947 - he felt himself to be needed more in Calcutta than in the official celebrations of independence in New Delhi - in desperation he announced that he and Suhrawardy had agreed to live together in a troubled area, to stop the killing. They moved to a large house in Beliaghata belonging to a Muslim businessman which was surrounded by Hindu slums. The police protected it while Gandhi received admirers, mostly women, wishing to hear him say something about the forthcoming independence of India. But Gandhi’s presence did have some calming effect on Calcutta during this period.

Despite the poisoned atmosphere in the city, Independence Day itself passed off peacefully in Calcutta, the streets thronged with people singing and embracing across the communal and caste divides, watched by huge posters of Gandhi, Nehru and Bose. (Not everyone was stirred, however: Satyajit Ray had absolutely no recollection of what he did that day.) At the stroke of midnight on 14/15 August 1947 women all over the city blew conch shells and lit ceremonial lamps. It was a time of joyousness - but for Calcutta the joy would be short-lived.