City of Learning

Although educated Bengalis have always responded to western culture with obvious interest and pleasure, formal education in Calcutta has been regarded mainly as a means of economic advancement. The city is obsessed with getting qualifications; when its biggest English-language newspaper, The Telegraph, announces annual awards for the best school in Calcutta, it is an occasion for much competition and publicity. During rush hours, schoolchildren are ferried to school in a strange contraption like a tin box, approximately a cuboid, with two facing benches, a roof and cut-out sidewindows, all of which sits on two wheels and is pulled by bicycle. As the box passes by, you may hear its occupants chanting lists of spellings (Bengali and English) and multiplication tables. Academically successful schools are much sought after by parents; with 13,000 pupils, South Point School in Ballygunj was listed in The Guinness Book of Records from 1984 to 1992 for having the largest number of pupils in the world until a Filipino school claimed the title. Parents of modest income often work long hours to send a child to a reputable school. At arrival and departure times in the respectable primary schools, mothers and fathers can be heard nagging their children about the homework carried in their heavy satchels crammed with books and papers. And as the time comes for a school’s annual tests, the entire household suspends its leisure activities so that the student can concentrate. When at last he or she passes the exam, it is customary to share with family and friends a box of milk-white or light-brown sandesh, a unique Bengali delicacy made from milk solids and either refined or unrefined sugar (the best sandesh is made from the newly harvested sugarcane). In Bengali, the word has a dual meaning, both as the name of the sweet and as the Bengali for “good news”. Sandesh is a part of all joyous occasions in Bengal. Try to buy it from the old-established confectioners Bhim Nag or Ganguram.

But perhaps the most impressive display of devotion to schooling is at the institutions run by welfare organizations for the children of the coolies who carry travellers’ luggage at Haora station. The coolie children come willingly to school but fly from their studies like a flock of pigeons as soon as a long-distance train pulls in. Their haste is a financial reflex, as they run to collect empty bottles from the carriages. Within ten minutes or so, however, they settle again at their interrupted lessons, calm and collected. As a teacher it was a heart-warming experience for me to witness this scene. There is no doubt that average seven-year olds in Calcutta have far better literacy and numeracy skills than their British or North American counterparts, at least those in the state-run system. For education is perceived to be the only way to escape from the harshness of life - as a coolie or as an ill-paid clerk.

Many schools trade on this belief by forcing parents to donate money on top of the official school admission fee, demanding as much as £2,500 per annum. Most English-medium schools ask euphemistically how much potential parents are prepared to pay towards “philanthropy”; the more they offer, the more likely their child is to gain admission. And once admitted, further demands for donations to school funds for computers, furniture, air-conditioners, generators, playground equipment and so on, flow in. If parents are unable to comply, their child suffers. Thus, seeking admission to a good school and educating children have become among the greatest stresses on Calcutta’s middle-class parents.

But learning purely for mental development rather than improving career prospects has never been totally absent from the educational picture in Calcutta. Individuals such as Dwarkanath Tagore and Iswarchandra Vidyasagar helped to establish schools and learned societies and foster the spread of education in Bengal for the general betterment of society. In the mid-nineteenth century, Rabindranath Tagore shunned conventional schools and was taught mainly at home in his family’s house at Jorasanko, immersed in a demanding, if stimulating environment (apart from his English lessons, which he hated). He went on to found his own school at Shantiniketan, outside Calcutta, in 1901 and later a university there, Visva Bharati, along with a centre for village development, which together were the inspiration behind the Dartington Trust and Dartington College of Arts in Devon, back in Britain. In the words of Leonard Elmhirst, who founded Dartington in 1925 after working with Tagore in Shantiniketan:

There was no aspect of human existence which did not exercise some fascination for him and around which he did not allow his mind and fertile imagination to play. Where, as a young man, I had been brought up in a world in which the religious and the secular were separate, he insisted that in poetry, music, art and life they were one, that there should be no dividing line.

Rabindranath despised the conventional, exam-oriented, textbookbased system in Calcutta’s schools that allowed no scope for the free play of curiosity, imagination and pleasure - particularly in the arts - in the process of learning. In a satirical fable published in 1918 called Tota Kahini (The Parrot’s Training), he tells of an ignorant but free bird who is put in a cage to receive a “sound schooling” at the whim of a raja and ends up stuffed with paper by the raja’s pundits and choked to death. (Copies of the book, amusingly illustrated, were sent to the members of the Calcutta University Commission.)

Today, Tagore’s educational ideal finds embodiment in many individual efforts to promote joyful spontaneous learning. One I know personally is north Calcutta’s Children’s Art Theatre, a non-profit organization which recently celebrated its twenty-fifth anniversary. It was set up by a group of parents who regularly meet at a venue in Bidhan Sarani (Cornwallis Street) at the weekends to encourage local children to develop their talents in arts and crafts, dance and music, drama and games. The children regularly perform at theatres and hold art exhibitions, but receive no payment. Apart from a few professional teachers, no one receives a salary.

Schools and Colleges

Before the British came, the nawabs and zamindars of Bengal encouraged education by making grants, known as inam, to learning establishments: Hindu pathshalas and Islamic madrassas; they also patronized learned men and a few women as court scholars. There is a coloured engraving of an old pathshala by the artist Solvyns on display in the Victoria Memorial. In Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali, a village pathshala is memorably depicted, in which the jovial local grocer supplements his income by teaching basic arithmetic and Bengali, while administering regular doses of corporal punishment with his cane. For higher, Sanskrit-based education, pupils would have to attend a tol run by pundits. In 1818 there were 28 such tols in the city, mostly situated in the Hatibagan and Simla areas of north Calcutta.

But it was the Christian missionaries of the nineteenth century who worked tirelessly to introduce mass education in Bengal, including the first elementary school for girls, founded in 1820. They taught in both Bengali and other vernacular languages and in English, with their pupils writing on sand, banana leaves, and palm leaves as well as slates and paper. The first local textbooks were produced by the Calcutta School Book Society founded in 1817 (no longer in existence), which had a close link with the missionaries in Serampore discussed in Chapter 3. In the first four years of its existence, the society printed 78,500 books - 48,750 of them in Bengali, 3,500 in English and the rest in Hindustani, Persian, Sanskrit and other languages.

Macaulay’s controversial minute on education of 1835, mentioned earlier, moved the course of Calcutta’s official educational institutions away from traditional learning and Indian languages towards the teaching of western knowledge in English. His motives were as much, if not more, pragmatic as philanthropic. Training natives as civil servants was far more cost effective than importing clerks from London. Nowhere in Calcutta will you see Macaulay’s educational ideas more confidently embodied than in the city’s oldest existing school, and one of its best, La Martinière in Loudon Street (now U. N. Brahmachari Street). Although founded (in 1835) as a gift from General Claude Martin to the “children of India”, for a century, until 1935, no Bengalis were admitted. La Martinière’s portico and tall Ionic columns, its Round Chapel, its four houses named after Charnock, Hastings, Martin and Macaulay, its Latin motto “Labor et constantia”, and its library of western classics - all bring to mind Macaulay’s notorious comment that “a single shelf of a good European library is worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia.”

Yet, as we know, the Bengali gentry supported English education. It opened up wider employment prospects for them and, of course, it brought them closer to western literature, science and philosophy. Although education in Calcutta has always remained a domain of conflict between Anglicists and nationalists, after 1854 the British recognized the responsibility of the government for education and established a system in which English would be used for higher studies by the few and vernacular languages for lower-level study by the masses. Three universities, in Calcutta, Madras and Bombay, were founded, with examining and degreegiving powers.

The prestige of Presidency College, located opposite Hare School on the northern side of College Square, dates from this time. It was the best source of western enlightenment for the babus of the nineteenth century, who flocked there in large numbers. Alumni in the early to mid-twentieth century included Subhas Chandra Bose, Satyajit Ray, and the city’s latest Nobel laureate, Amartya Sen. In the 1960s the college became a hotbed of Naxalite activity. In India: A Million Mutinies Now, Naipaul describes the atmosphere for the young science student then at Presidency who later became a Naxalite:

One night [he] was coming back from South Calcutta by bus. He saw a crowd in the grounds of Presidency College. He got off the bus to see what it was about. He didn’t find anyone he knew, but the next day, when he went back, he discovered that the leaders of the student movement, and others, were his friends. He began to spend more and more time with those friends, in Presidency College, in the coffee house opposite, and in the college hostel.

He began to do political work among the students who were not committed.

Since then, the standard of Presidency has somewhat declined with the Left Front government’s anti-elitist stance on education, and some of the best lecturers have moved to other institutions. But it remains the city’s most significant educational institution at college level.

Calcutta Cricket Club: Sport

English education and ideology inevitably brought in their wake English sports like cricket, hockey, rugby, football, tennis and golf, mainly from around the early part of the nineteenth century. Calcutta Cricket Club, founded in 1792, is generally regarded as the oldest cricket club outside the British Isles. The first organized match, watched by the bemused natives, was played on the Maidan in January 1804 between the Old Etonians (who were in Calcutta as East India Company writers) and the nonEtonians, designated as “Calcutta”. The Etonians won, with Robert Vansittart scoring a century.

Fifty years later, in 1854, the club managed to secure a permanent playing field at the Eden Gardens (named after the two sisters of Lord Auckland who nurtured the two square miles of park land and gifted it to the citizens of Calcutta for recreation and enjoyment). Apart from the cricket ground, which has a capacity for 85,000 spectators, the Eden Gardens contain an indoor cricket stadium, two sports complexes, a band stand, a Burmese pagoda, and the prominent Akashbani Bhavan - Calcutta’s radio station; it also has space for equestrian activities.

The first English cricket team visited the city in 1888-89 and the first MCC tour took place in 1926-27. Sarada Ranjan Ray, a grand-uncle of Satyajit Ray, is reputed to have introduced the game to the Bengalis in the 1870s and was dubbed by the British the “W. G. of India” (after the immortal W.G. Grace). During the twentieth century cricket become wildly popular, and it is played all over the city in the evenings and at the weekends, wherever there is some space - which means in the many quieter side streets, as well as on the Maidan and in the other parks. On the days when the trade unions call for a general strike, people even set up a wicket on the tram tracks and start to play. Now the sport has received a further boost as Calcutta is basking in the reflected glory of another Bengali cricketer. The captain of the Indian team from 2000 to2005, Saurav Ganguly, made his test debut at Lords in 1996 at the age of twenty-four with a masterful century. When he scores, Calcuttans beat drums and blow horns. With him as a role model, thousands of Bengali middle-class parents are sending their boys for expensive coaching. Suddenly cricket is perceived as a viable career, alongside the more traditional pursuits of medicine and the civil service. Biographies of Ganguly - there are already several in Bengali - are selling well, partly for lack of any other Bengali heroes but also because Ganguly is the quintessentially Bengali bhadralok: charming, cultured, charitable and hospitable, showing none of the aggressive characteristics apparently admired elsewhere in Indian cricket.

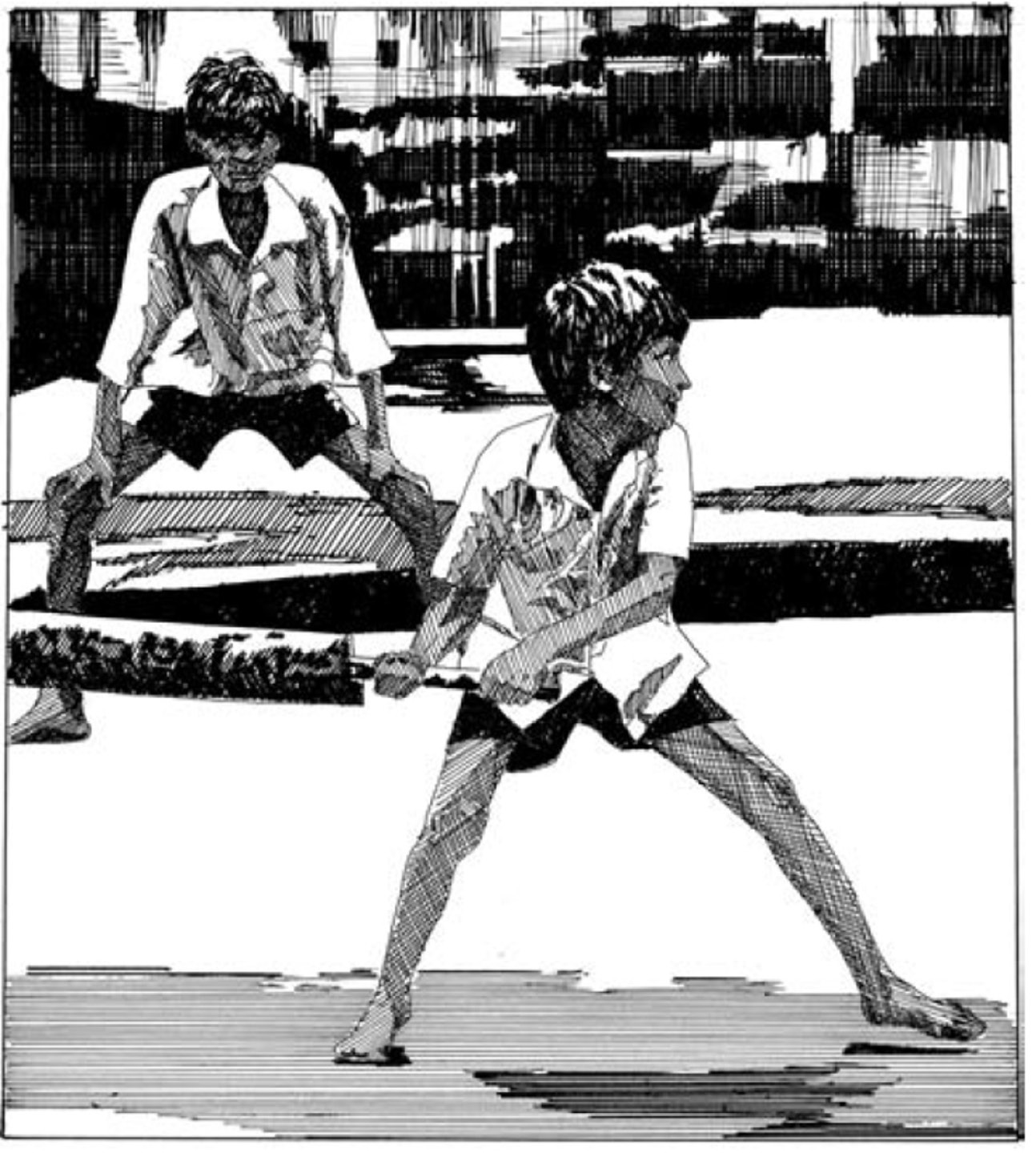

Street cricket

After cricket, football (or soccer) is the most popular sport. The first club was formed at Presidency College in 1884. Students of Presidency founded further clubs when they left the college, and in 1893 the Indian Football Association was formed. Bengal’s favourite team is Mohon Bagan, founded in 1889. When it won the IFA Shield in 1911, defeating the East Yorkshire team 2-1, Bengalis in Calcutta were ecstatic. After the partition of India in 1947, Mohon Bagan regularly played against the East Bengal Club founded in 1921, which enjoyed the support of the refugees from East Bengal living in the city. The third popular club is the Mohammedan, supported by local Muslims.

Tennis, hockey, wrestling and body-building also attract a lot of enthusiasm; Monotosh Roy became the first Indian Mr. Universe in 1951. Golf, too, appeals to a small number of wealthier Calcuttans because the Tollygunj Club has an excellent course. Women, not surprisingly, are less involved in sport, though they started to play after independence. In the 1952 Helsinki Olympics two Bengali women took part, the athlete Nilima Ghosh and the swimmer Arati Saha, who in 1959 became the first Asian woman to swim the English Channel, while in 1988 Soma Datta competed in rifle-shooting at the Seoul Olympics.

Laboratories and Discoveries: Science in Calcutta

It was Rammohan Roy who first made the case for science education in India. Writing to the governor-general in 1823, he demanded a system of instruction in mathematics, natural philosophy, chemistry, and astronomy “with other useful sciences”. Through his initiative and that of Dwarkanath Tagore, the Calcutta Medical College was established in 1835 to train doctors. The following year, when a Bengali instructor, Madhusudan Gupta, dissected the first human corpse, guns were fired at Fort William to celebrate the great event, although Gupta was ostracized by orthodox Hindus. (Prior to this, wax models had been used for teaching dissection, in deference to religion.) Dwarkanath also sent four young Bengali men to England to study medicine in 1839, and paid the entire expenses incurred by two of them.

The other noteworthy institution for science at this time was St. Xavier’s College in Park Street founded in 1860 by Belgian Jesuits. It remains a sought-after college today, though not especially for science. St. Xavier’s produced India’s first modern scientist, Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937), who read physics at the college before going to Cambridge, achieving a brilliant result in the tripos, and eventually returning to Calcutta as the first Indian professor of physics at Presidency College. But since he was offered two-thirds of the salary granted to the European professors, in protest he refused to accept any salary at all, while continuing to teach; eventually the government conceded.

Funds were not easily forthcoming from Bose’s countrymen either. Tagore was Bose’s greatest Bengali advocate and raised money from the maharaja of a local state to enable Bose to stay in Europe in 1900 and carry on his research. Commenting on the prospect of his future glory and its effect on Bengali society, Rabindranath Tagore wrote wryly to Bose:

...when victory is yours, we too - all of us Bengalis - will share in the honour and the glory. We do not need to understand what it is you have done, or to have given you any thought, time or money; but the moment we hear the chorus of praise in The Times from the lips of an Englishman we shall lap it up. Some important newspapers in our country will observe that we are not inferior men; and another paper will observe that we are making discovery after discovery in science. ...

Sowing and ploughing you will do alone; reaping we shall do together.

Scientifically, Bose had two distinct careers. Before 1900 he was a physicist, whose pioneering work in the late 1890s on the effects of electromagnetic radiation on metals received invaluable early recognition in the West, and contributed to the development of wireless telegraphy and radio. But, unlike the business-minded Marconi, Bose refused to patent his inventions because he believed that financial gain was inappropriate for a true scientist. After 1900, he extended his study to the effects of radiation on plant and animal tissues. He invented and built some highly ingenious and sensitive apparatus to reveal striking but debatable similarities in the responses to electrical stimulus of living and non-living substances. His instruments can be viewed with special permission at the Bose Research Institute at Lower Circular Road (now Jagadish Chandra Bose Road), which he founded in 1917. Although this later physiological work was greeted with less enthusiasm in the West than his work as a physicist, Bose became a celebrity, was given a knighthood, and in 1920 became the first Indian scientist to become a fellow of the Royal Society (following the first Indian fellow, the mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan).

The bacteriologist Sir Ronald Ross (1857-1932), a member of the Indian Medical Service, worked in Calcutta for a brief period in the 1890s and discovered the cause of malaria there, for which he was awarded a Nobel prize in 1902. It was in a tiny laboratory in Calcutta’s Presidency General Hospital (now with the tongue-twisting name Seth Sukhlal Karnani Memorial Hospital, abbreviated as SSKM Hospital), that Ross established how mosquitoes transmit the malarial parasite in their bite. A commemorative tablet at the entrance to the hospital carries a verse composed by Ross (who fancied himself as a poet):

This day relenting God

Hath placed within my hand

A wondrous thing; and God

Be praised, at his command

Seeking his secret deeds

With tears and toiling breath

I find thy cunning seeds

O million-murdering death.

I know this little thing

A myriad men will save.

O death where is thy sting

And Victory, O grave?

One of the new, post-colonial street names of the city is Ronald Ross Sarani. The city authorities always include Ross in the roster of Calcutta’s Nobel laureates.

Although the south Indian physicist Sir Chandrasekhara Venkata Raman (1888-1970), who also won a Nobel prize, is primarily associated with the Indian Institute of Science at Bangalore, the work for which he is best known was done in Calcutta. He arrived in the city from Madras in search of a job in 1907, and in 1917 became professor of physics in Calcutta’s new University College of Science at Rajabazar, in the south. During a voyage to Europe in 1921 he became fascinated by the azure hue of the Mediterranean’s water. He decided to find out more about the scattering of light by different substances, and his experiments demonstrated a change in the wavelength of light when a light beam is deflected by molecules, best explained by regarding the light beam not as a wave but as a stream of particles: an important piece of evidence for the truth of quantum theory. His discovery of this “Raman effect” won him the Nobel prize in 1930, three years before Raman left Calcutta after a sharp dispute with his Bengali colleagues.

In chemistry, the city’s most notable figure is undoubtedly Sir Prafulla Chandra Ray (1861-1944). Like Bose, Ray joined the staff of Presidency College after studying in Calcutta and completing his degree in England. Again like Bose, he was discriminated against over pay, but he set up a good laboratory and turned his attention to both pure and applied science. My father knew Ray personally and told me that as well as being an inspiring teacher, he was a man of immense practical vision who favoured a democratic approach to science rather than the hierarchical one typical in India - though he was also a passionate nationalist (and later became a devoted supporter of Gandhi). This led to his almost single-handed founding of Bengal Chemicals in 1892, and the writing of his two monumental volumes, The History of Hindu Chemistry. In 1900 the firm became the Bengal Chemical and Pharmaceutical Works and began to manufacture drugs, toiletries and cosmetics of a high standard - both from the western pharmacopoeia and from the ancient Indian Ayurvedic system. From 1904 it operated from 82 Maniktola Main Road under the management of another remarkable man, Rajsekhar Basu, who later become a famous humorous writer in Bengali. Ray was also instrumental in establishing the Bengal Pottery Works, the Calcutta Soap Works, the Bengal Enamel Works, and the Bengal Canning and Condiment Works. His essays on many subjects show a remarkable clarity and power of expression in both English and Bengali.

Among the next generation of scientists, the most remarkable was probably Satyendranath Bose (1894-1974), who unusually among Calcutta scientists never studied abroad. An outstanding student at Presidency College, he left Calcutta in 1921 and went to teach in Dacca (Dhaka). From there he sent a paper to Einstein, who himself translated it into German and published it in the journal Zeitschrift für Physik. Their contact led to the development of the Bose-Einstein statistics in 1924-25 regarding the gas-like qualities of electromagnetic radiation, which account for the cohesive streaming of laser light and the frictionless creeping of helium when cooled until it becomes a superfluid - and the behaviour of subatomic particles now known as bosons. Bose returned to Calcutta in 1945 to teach at the university where he founded a laboratory for studying X-ray crystallography and thermo-luminescence. Calcutta’s latest centre for basic science at Salt Lake was named after Satyendranath Bose (not to be confused with the already-mentioned Bose Research Institute named after J. C. Bose). Tagore dedicated his science primer Biswa Parichay (Our Universe) to Bose, who loved literature and was also a competent player of the esraj, the Indian violin. Indeed, according to an Indian physicist, “Bose loved science but he loved literature even more.”

Other pioneering scientists of Calcutta include the astrophysicist Meghnad Saha; U. N. Brahmachari, who discovered a treatment for the dread disease kala azar and founded Calcutta’s blood bank (the world’s second such bank); the applied psychologist Girindrasekhar Bose, who founded the mental home at Lumbini Park; and the statistician Prasanta Mahalanobis, founder of the Indian Statistical Institute at Baranagore, who became a key figure in Indian national planning in the 1950s.

The study of science remains popular among bright students of the city, but as soon as they pass their first examinations, they are often picked up by universities and institutions abroad, particularly in the United States and Canada. Those who stay tend to seek out opportunities elsewhere in India or spend much time on lecture/study trips abroad in order to keep pace with innovations in their field. Visit the libraries of the United States Information Service or the British Council and you will soon sense the keenness of young Bengalis to study science overseas. Apart from the atom smasher at the Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics at Salt Lake, there is a lack of advanced research facilities in Calcutta, a stifling atmosphere of mediocrity in the educational institutions, and frequent interruptions to work due to strikes. The city’s scientific brain drain is endemic, and in the absence of serious initiatives by the state government, it will continue.

To kindle interest in science among the younger generation, a public science park - the first of its kind in India - was recently set up at the crossing of the Eastern Bypass and J. B. S. Haldane Avenue (the biologist Haldane emigrated to India and worked at the Indian Statistical Institute for a while in the late 1950s). The architecture is space age, consisting of solid geometrical shapes set among trees and lawns, and the galleries display interactive exhibits on mechanics, sound, optics, geography, environment, space (there is a planetarium), time machines, biology, information technology and much else; there is also a 2,000-seat conference hall.

A Love Affair with English

Long before Macaulay promoted English as the preferred medium of higher education in India - in the humanities as much as in the sciences - the inhabitants of Calcutta had naturally embraced the language as a means of communication with the Company traders. Individuals such as Raja Nabakrishna Deb, Warren Hastings’ Persian tutor and Clive’s ally against Siraj-ud-Daula, and Raja Darpa Narayan Tagore, the ancestor of one branch of the Tagore family, had picked up the language while working for the British as commercial middle men. The washerman Ratan Sarkar was even able to overcome the rigid caste hierarchy and become wealthy by exploiting his self-taught knowledge of English. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, Bengalis like Andiram Das and Ramram Misra had set up schools for teaching elementary English to native employees of the Company. The arrival of the missionaries, with their zeal for print, made English still more accessible to Bengalis.

Gradually, English became the accepted medium of both administration and education in the city. India’s first modern journalist, Ramananda Chatterjee (1863-1943), ushered in serious journalism by Indians in English through his monthly journal The Modern Review. Daily newspapers such as The Statesman, established in 1875, the older Amrita Bazar Patrika and The Telegraph, established in the early 1980s, all published in Calcutta, have capitalized on the growing need for reporting and analysis in English. Although the circulation figures of the Bengali-language press, notably the daily Ananda Bazar Patrika, are still higher than for the English-language press, the trend is towards reading in English. In terms of numbers of English speakers, the Indian subcontinent ranks third in the world, after the US and the UK. If you tune into conversations on the streets of Calcutta, you may be surprised to notice the high incidence of English words, many of which are pronounced in a way that sounds incongruous to western English-speaking ears.

The most significant difference between the way English is spoken in Calcutta and in an English-speaking country lies in the rhythm, composed of stressed pitch, loudness, speed and silence. Words like “university” or “psychology”, for instance, sound like “ini-ver-citi” and “sycologi”. There is also confusion about the position and manner of articulating certain sounds, for example where to place the tongue when pronouncing English words containing “th”, or how to use the soft palate to pronounce initial consonants like “p” or “b”. Most Bengalis pronounce “v” as “bh”, while words beginning with “qu” are perhaps the hardest, hence “question” comes out as “koschen” and “quote” as “kote”. It may take a foreigner a little while to get used to Bengali-English pronunciation, but the sensitive listener cannot fail to notice the originality and richness of expression which are the prerogative of some talkative bilingual Bengalis. And then, of course, there are the words that have entered English from Bengal as a result of the colonial period, such as “bungalow”. Here I recommend an enjoyable dip into the famous Hobson-Jobson, a glossary of Anglo-Indian words and phrases.

In writing English, the most common mistakes made by Bengalis used to thinking in their own language are in singulars and plurals, prepositions and word order. Tagore captured the grammatical and syntactical situation beautifully in a letter he wrote from England to his Bengali niece a few months before he won the Nobel prize (for his own translations of his poetry into English) in 1913. Of course, the original letter is in Bengali and this is a colloquial translation:

The English language has many pitfalls - think of the definite and indefinite articles, the prepositions, the use of “shall” and “will” - which cannot be grasped by intuition, only by tuition. I have reached the conclusion that these elements are like insects that have burrowed into my subliminal consciousness. When I blindly set sail with my pen, these little creatures creep silently out of their dark holes and perform their appointed tasks - but as soon as I consciously focus upon them they go higgledy-piggledy. And so I never feel confident of controlling them, and even now I say I do not know the English language. In stating this I perhaps exaggerate a little - actually I know English well enough to say that I do not know it. That is the truth.

In fact, Tagore knew English pretty well and he improved through contact with friends like the missionary C. F. Andrews, the littérateur E. J. Thompson (father of E. P. Thompson), and Leonard Elmhirst, the founder of the Dartington Trust. Nevertheless, his power of expression in English was still way below that in his own language Bengali. And since 1947, with the withdrawal of Englishmen and women from India, the general standard of both spoken and written English in Calcutta has undoubtedly become less expressive and more of a mishmash lingo known as Benglish (an admixture of Bengali and English) or Hinglish (Hindi and English), notwithstanding the clarity and vigour of a few writers in English such as Nirad C. Chaudhuri, Satyajit Ray and some others. English continues to thrive in the city as one of the thirteen languages listed in the Constitution.

Indian English Fiction

If the general standard of English has become more home-spun, the quality of a few sophisticated writer of English literary fiction has secured international acclaim. Of course, most of these writers, even though they have written about Calcutta and have some roots there, have lived outside the city for long periods and compare themselves with writers of English and American fiction. Among them are Kunal Basu, Amit Chaudhuri, Anita Desai, Amitav Ghosh, Jhumpa Lahiri, Bharati Mukherjee, as well as the Mills and Boon-style writer Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni. Each of them deals with his or her experience of Bengal in a unique way but all have felt a compulsion to grapple with their relationship to the city and have found it a rich source of material. Even Vikram Seth, not a Bengali but who was born in Calcutta, felt compelled to recreate the linguistic complexity of the city in his portrait of the Chatterji family in the novel A Suitable Boy. The Chatterji elders are portrayed as almost congenitally reverential to Tagore - so much so that their children predictably turn rebellious.

Without having the space in this book to delve into these writers in depth, I should like to give a flavour of their differing reactions to Calcutta by quoting briefly from their stories and novels. Kunal Basu, for instance, tries in his debut novel The Opium Clerk (2001) to make sense of the mysteries of the colonial merchant city through the eyes of a Bengali opium clerk born in 1857. Here he evokes Kidderpore docks where the cargo ships used to moor:

Leadsmen waiting to take charge of incoming and outgoing ships had set up surface nets - large bags tied to spars and held in the water by menials. The catch usually consisted of shrimps, swarming at the water’s surface, bumalo, pomfret, and silver fish used as bait. Sometimes a sailor would holler in excitement at a river snake caught in the nets. They would rush down the masts or break away from scrubbing gullies, and chatter over the yellow and black creature, lifting it up by its tail. Captains usually took notice too, especially with rare marine fauna, strange-coloured shells, or sea-spiders. Men were instructed to soak these in spirits and keep them in glass jars till a junior officer found time to take a batch over to the Calcutta Museum.

Anita Desai, born in Mussoorie and brought up in Delhi, prior to first living in Calcutta after her marriage, visualized the place through her Bengali father’s nostalgic feelings about his homeland. But when she went there in the late 1950s, her romantic notion of the place “was rapidly and drastically modified.” She recalled the experience of being in a “metropolis that made Delhi seem a village by comparison.” In her delicately structured story, “Private Tuition by Mr. Bose”, she poignantly captures the predicament of a dreamy teacher of poetry condemned to giving mundane Sanskrit tuition to bored and hopeless students. Calcutta abounds in such sad characters full of suppressed emotions. In a few expert strokes she conjures up the sounds, smells and sights of the city:

Pritam, the scabby, oil-slick son of the Brahmin priest, coughed theatrically - a cough imitating that of a favourite screen actor, surely, it was so false and over-done and suggestive. Mr. Bose swung around in dismay, crying, ‘Why have you stopped? Go on, go on.’

‘You weren’t listening, Sir’.

Many words, many questions leapt to Mr. Bose’s lips, ready to pounce on this miserable boy whom he could hardly bear to see sitting beneath his wife’s holy tulsi plant that she tended with prayers, water-can and oillamp every evening. Then growing conscious of the way his moustache was agitating upon his upper lip, he said only, ‘Read’.

‘Ahar va asvam purustan mahima nvajagata...’

Across the road someone turned on a radio and a song filled with a pleasant, lilting Weltschmerz twirled and sank, twirled and rose from that balcony to this. Pritam raised his voice, grinding through the Sanskrit consonants like some dying, diseased tram-car. From the kitchen only a murmur and the soft thumping of the dough in the pan could be heard - sounds as soft and comfortable as sleepy pigeons. Mr. Bose longed passionately to listen to them, catch every faintest nuance of them, but to do this he would have to smash the radio, hurl the Brahmin’s son down the iron stairs... He curled up his hands on his knees and drew his feet together under him, horrified at this welling up of violence inside him, under his pale pink bush-shirt, inside his thin, ridiculously heaving chest.

Though Amitav Ghosh was educated mainly outside Bengal, according to his own account he developed many of his notions of Bengal from the films of Ray: “Many of my images have come from Satyajit Ray. They are part of my internal landscape, part of the way I now see Bengal in my mind’s eye. It is a great fortune for me that Ray has made films about a particular milieu from which I happen to come as well, so that what he says about Bengal and what I feel about it are in so many ways totally intermingled.” His portrait of his formidable grandmother from East Bengal in his novel The Shadow Lines (1988) and his description of a refugee colony have some of the clarity of Ray’s films about the seedier side of Calcutta:

We turned off Southern Avenue at Gole Park, and found, inevitably, that the gates of the railway crossing at Dhakuria were down. We had to stew in the midday heat for half an hour before the gates were lifted again. We sped off past the open fields around the Jodhpur Club and down the tree-lined stretch of road that ran along the campus of Jadavpur University. But immediately afterwards we had to slow down to a crawl as the road grew progressively narrower and more crowded. Rows of shacks appeared on both sides of the road now, small ramshackle structures, some of them built on low stilts, with walls of plaited bamboo, and roofs that had been patched together somehow out of sheets of corrugated iron. A ragged line of concrete houses rose behind the shacks, most of them unfinished.

My grandmother, looking out of her window in amazement exclaimed: ‘When I last came here ten years ago, there were rice fields running alongside the road; it was a kind of place where rich Calcutta people built their garden houses. And look at it now - as filthy as a babui’s nest. It is all because of the refugees, flooding in like that.’

‘Just like we did,’ said my father, to provoke her.

‘We’re not refugees,’ snapped my grandmother, on cue. ‘We came long before Partition.’

Amit Chaudhuri, like Ghosh, grew up in Bombay, but now lives in Calcutta. His first novel, A Strange and Sublime Address (1991), subtly records his childish and adolescent impressions of visits to relatives in Calcutta. He said of the book, “I had no intention of telling a story, or of conveying any political feelings - I wanted to convey what it was to be alive in that place.” For his child character, the sprawling and indifferent metropolis is also delightful and magical - as I too recall of my childhood there. During a power-cut (endemic to the city from the 1970s until the 1990s), the whole city would suddenly fall under the cloak of a tropical night sky. With the return of artificial light, suddenly there would come a different kind of magic - something like the magic of Snow White’s awakening - exhilarating to everyone:

Each day there would be a power-cut, and each day there would be the unexpected, irrational thrill when the lights returned; it was as if people would never get used to it; day after day, at the precise, privileged moment when the power-cut ended without warning as it had begun, giving off a radiance that was confusing and breathtaking, there was an uncontrollable sensation of delight, as if it were happening for the first time. With what appeared to be an instinct for timing, the rows of fluorescent lamps glittered to life simultaneously. The effect was the opposite of blowing out candles on a birthday cake: it was as if someone had blown on a set of unlit candles, and the magic exhalation had brought a flame to every wick at once.

The last two extracts are about Bengalis living abroad and thinking about Bengal. Both writers live in the United States. Bharati Mukhejee was the first to write about the lives, loves and disappointments of Bengalis living physically in the US but mentally still in Bengal. At her best she sketches them with penetrating irony and wit. Here, in “The Tenant”, a liberated single woman at a US university, Maya Sanyal, has unwillingly drifted into having tea with a conventional physics lecturer, Dr. Rab Chatterji, and his wife:

‘What are you waiting for, Santana?’ Dr. Chatterji becomes imperious, though not unaffectionate. He pulls a dining chair up close to the coffee table. ‘Make some tea.’ He speaks in Bengali to his wife, in English to Maya. To Maya he says, grandly, ‘We are having real Indian Green Label Lipton. A nephew is bringing it just one month back.’

His wife ignores him. ‘The kettle’s already on,’ she says. She wants to know about the Sanyal family. Is it true her great-grandfather was a member of the Star Chamber in England?

Nothing in Calcutta is ever lost. Just as her story is known to Bengalis all over America, so are the scandals of her family, the grandfather hauled up for tax evasion, the aunt who left her husband to act in films. This woman brings up the Star Chamber, the glories of the Sanyal family, her father’s philanthropies, but it’s a way of saying, I know the dirt.

Jhumpa Lahiri, the youngest of these writers, born in England and brought up in the US and thus only a visitor to Calcutta, writes in a brilliant story, “Mrs Sen’s”, about her mother’s generation, who were almost perpetually homesick and looked for comfort in reinventing a Bengali atmosphere in an alien environment: by listening to Bengali songs on cassette, reminiscing about monsoon flooding in College Street, and waiting expectantly for blue aerogrammes from home. Mrs. Sen is the thirty-yearold wife of an economic migrant who does not really like living in Boston. She still uses her Bengali bonti, a chopper with a curved upright blade, instead of a knife, for chopping vegetables, and craves to cook fresh fish using her authentic and favourite Calcutta recipes. But she cannot get the right fish from the local US supermarket. Having grown up eating fish twice a day, she says proudly: “in Calcutta people ate fish first thing in the morning, last thing before bed, as a snack after school if they were lucky. They ate the tail, the eggs, even the head. It was available in any market, at any hour, from dawn until midnight. All you have to do is leave the house and walk a bit, and there you are.” (Most Bengalis love fish and are renowned for interesting recipes such as baked hilsa in mustard (sorsheilish), carp in yogurt (doi machh), prawns in coconut sauce (malaikari) and fish heads with vegetables (murighanto).)

Ten years ago Anita Desai appropriately asked:

Can the English language convey thoughts, emotions and situations that are alien to English experience? What about those that have grown out of the contact of the two languages, a contact which has infiltrated many English words into Bengali (and a few vice versa, such as bungalow), where they have taken on a connotation and flavour very different from their usage in English?

The answers remain unclear. The huge success of Indian writers in English in recent years suggests that English can cope with any experience. But when I have translated Tagore and other excellent Bengali writers into English, I have often felt that their excellence cannot be adequately conveyed. Using lots of Bengali words within the English text, as some of the above writers do, is generally unsatisfactory. It may give an appearance of authenticity, but fails to meet the literary challenge of conveying the atmosphere of a different culture. When you look at Satyajit Ray’s films about Calcutta through Bengali eyes and ears and then through foreign eyes and English subtitles - or for that matter read the masterly stories of R. K. Narayan, who generally eschews Indian words - you realize that the gap between cultures cannot be erased by using vernacular words within English sentences; the problem is more subtle and difficult.

The issues concerning the growing use of English in Calcutta are fiercely and emotionally debated among the city’s writers and intellectuals. Whatever the outcome, the English language will always be an integral part of Calcutta’s cosmopolitan ethos. And with the embracing of satellite television, email, chat rooms and the internet in the 1990s, English is fast becoming the pan-Indian language that Macaulay called for nearly two centuries ago. Whether he would have been pleased with what Bengalis are writing in this, their own English, one can only speculate.