City of Strife

After 1947, Calcutta increasingly became a city of migrants - mainly coming into the city, but also leaving it. The Chinese community, for example, which was about 50,000 strong in 1947, first grew - following the Chinese revolution of 1949 - and then slowly shrank, as its members emigrated to Canada, Australia, the United States and Hong Kong. By the end of the century, there were only ten thousand Chinese in Calcutta.

Like the Armenians, the Jews and the Marwaris, the first Calcutta Chinese were economic migrants. Around 1780, Yong Atchew received a grant from Warren Hastings of some land and money to set up a sugar plantation. More than 100 countrymen came to work it, and a subsidiary business sprang up distilling arrack. Soon these early immigrants were joined by deserters from ships, while a group of shoe-makers and tanners from Hakka district in China settled in Old China Bazaar Street at Barabazar, where their descendants still make cheap but satisfactory shoes. Today, most of the community are Indian citizens, hard working and prosperous, though forming a relatively closed community with its own mini-Chinatown, like expatriate Chinese the world over. As mentioned earlier, this Chinatown was once in Chitpur Road - where it even had its own opium dens - but it is now elsewhere. The post-independence Calcutta Corporation made a concerted effort to develop that area with multi-story business premises, and so the Chinese moved to Tangra in the east on the way to the airport, where they set up tanneries. Tangra has a Chinese school, social clubs, specialist shops and two newspapers, and restaurants that serve savoury and clean food at a reasonable price. Only the Sea Ip Temple in Chhatawalla Goli remains in the Chitpur area, marking the original Chinese connection. It is difficult to locate, being hidden by taller buildings, but it can be recognized by its curved roof with two huge porcelain fish standing on their tails. Inside is a dusty collection of old Chinese weapons.

Yet the commercial basis of Calcutta’s Chinatown is now under threat. In 2002, the state government ordered the closure of 530 tanneries in Calcutta on environmental grounds, more than 150 of them Chinese-owned, and their relocation away from the city in the neighbouring district of 24 Parganas. But the new location lacks adequate infrastructure, and the Chinese leather-makers are furious; they say they will move right out of West Bengal, to Kanpur or Madras (Chennai), and that could mean the end of the leather industry in West Bengal and the loss of half a million jobs. However, it will not mean the end of the Chinese in the city, who have moved into pharmaceutical production and food processing, producing sauces and sea food for a global market. Calcutta will continue to celebrate Chinese festivals with illuminations, dragon dances and fireworks in Tangra, and paper lanterns and bunting in the Chinese restaurants of Park Street, along with the preparation of special dishes like sau chu (roasted whole pig). On the fifteenth day of the Chinese New Year, the Calcutta Chinese will continue to visit the gleaming tomb of Atchew in Achipur, an eastern suburb close to Diamond Harbour, and the Taoist temple nearby. The community, like the Parsees, though small in number, will go on thriving as it has for over two centuries. Highly intelligent and industrious, Parsees have always been in the city. In 2004 UNESCO held the 3000th anniversary of Zoroastrian heritage in the city. The Fire Temple at Metcalfe Street is certainly worth a visit.

The same cannot be said of the Jewish community, which was much depleted after 1948 when most of its members left for the new state of Israel. The synagogue and the bakery Nahoum’s in New Market, are the only remaining traces of the Jewish presence in the city. The city’s original Jews arrived soon after Charnock and gradually grew in number until they were two thousand strong in 1900. The earlier migrants came mainly from Baghdad, with a later group coming from Romania during the Second World War. During the nineteenth century, they prospered by dealing in jute, tobacco, coal, and property, and became notably westernized, speaking English in public. Their contribution to Calcutta’s hospitals was substantial. Elias David Joseph Ezra, the first Jew to become sheriff of Calcutta, erected the Maghen David Synagogue on Canning Street in 1884, where it still stands with resplendent coloured glass windows, a vaulted roof and an ornate altar.

Refugees from East Bengal

By far the biggest migration into the city consisted of Hindu refugees from East Bengal, fleeing from discrimination and persecution in what had become East Pakistan. Although there are no reliable statistics on this exodus, by the time of the 1951 census a mere one-third (33.2 per cent) of the inhabitants of Calcutta were recorded as having been born in the city, with everyone else being an immigrant: 12.3 per cent were from neighbouring villages, 26.6 per cent from other Indian states, and 26.9 per cent - more than a quarter of the population - were from East Pakistan, as a result of the communal troubles that had raged since 1907 and the 1947 partition.

The big migration began in the early 1940s, a steady flow of middleclass people who already had family and business ties with Calcutta and therefore could look after themselves financially. These people gradually bought houses from Muslims who were moving out of the city in the opposite direction, and settled down fairly well despite imposing a strain on the city’s resources of housing and employment.

Then came an uncontrollable wave of refugees. Three quarters of a million of them washed up in Calcutta during 1948-49. In 1950, well over a million entered West Bengal. They included both the middle class and the rural poor, who had been forcibly uprooted, unlike the earlier migrants. Some - about a quarter of the 1950 influx - settled in relief camps known as “colonies”. In 1949, there were more than 40 colonies in southeast Calcutta and some 65 in the north. Their “housing” consisted of temporarily built thatched huts, water drawn from a standpipe, and sanitation arrangements that were insufficient. Conditions were severely overcrowded and squalid. Yet these shabby clusters of shelters had grand names like Adarsha Nagar (Ideal City) and Bijoygarh (Victory Town) - the second of which still exists, though no longer as a shanty town but as a busy southern suburb. An original resident of the Bijoygarh colony told me stories of remarkable human resilience, resourcefulness, good neighbourliness and compassion in those early days. When a tropical storm blew down some of the flimsy shacks in the middle of night, their occupants would be welcome to huddle under the equally vulnerable ones of neighbours, and as soon as the storm had passed, everyone would get busy rebuilding the demolished shacks. If there was a malnourished baby in the community, people would club together to buy milk for the child. There were long queues to collect a single bucket of water from the standpipe and to use the communal lavatories. But in general the refugees never lost patience and hope. Half a century on, my elderly informant was living in a decent brick house with his family who knew little of the plight of the first generation. “We were survivors. We coped,” he said very quietly, almost as if speaking to himself. His sons and daughters, born in Calcutta, have no trace of an East Bengal accent, unlike their father.

Not content with the inadequate facilities of the colonies, some of the more enterprising refugees started to squat in empty houses in the city’s suburbs. This is the first time the word “squat” and its new pan-Indian equivalent, jabar dakhal, came into ordinary conversation. There were a substantial number of such empty properties following partition, including the grand colonial houses of the departed British. So great was the tide of potential squatters that the police could not prevent them from taking over many of these empty buildings.

In addition, the West Bengal Government’s ministry of rehabilitation opened empty warehouses and berthed steamers on the Hugli as temporary shelters. The platforms and concourses of the two main railway stations at Haora and Sealdah filled up, too, with bewildered refugees. Still more came after the dispute over Kashmir in 1951, and the entire city became a refugee relief centre. The refugees were camping in the streets, scratching a living by setting up tea shops and tiny kiosks selling cigarettes and pan. Listless and bored, they spat the blood-red juice from chewing pan all over the city’s walls and pavements, not bothering with a spittoon. Lacking any kind of sanitation, they defecated in the open gutters. Babies were born on the railway platforms and open streets without much ado, let alone medical treatment. The streets were alive with rats, cockroaches and flies, and scavenging dogs and vultures. Refugees who were near death were sometimes carried by relatives to the Kalighat temple for the last rites. They were the lucky ones.

Mother Teresa

These were the conditions that gave birth to the legend of Mother Teresa. On 22 August 1952, a feast day dedicated to the Immaculate Heart of Mary, she opened her famous home for the dying, Nirmal Hriday (Sacred Heart) next to the Kalighat temple, in a house that was once a pilgrims’ hostel but at the time was occupied by local goondas. She had obtained the property from the Calcutta Corporation through her personal contact with Bidhan Chandra Roy, the chief minister of West Bengal from 1948 until 1962.

As mentioned in the Introduction, the Albanian-born Sister Teresa (1910-97) had been in the city since 1931. She knew very well of its vulnerability to disaster such as the famine of 1943-44, and of its oppressive climate. Walking the streets in 1948, she saw the human catastrophe of the refugees and was moved to pity. Although her request to Rome for permission to found a new order in Calcutta was not immediately granted (the pope sanctified the order in 1950), she bided her time, contemplating her religious duty and working out an action plan. With an uncanny understanding of the psychology of charity, she knew that the images of dying human beings on the streets of Calcutta would trouble an affluent West and generate massive support for her Missionaries of Charity.

For two decades, she worked quietly in Calcutta, unheralded by the world. The famous image of Mother Teresa of Calcutta - her wrinkled face hooded in a blue-bordered simple white cotton sari with her hands folded in a namaskar - dates from the late 1960s. In May 1968, a BBC television Sunday-night programme, Meeting Point, presented by Malcolm Muggeridge (who had known Calcutta as a journalist on The Statesman in the 1930s), beamed appalling images of Calcutta’s poverty into British homes along with the dedicated work of the Missionaries of Charity. Muggeridge even claimed that a miracle had occurred in the filming; despite the low light level inside Nirmal Hriday, his cameraman had been able to work successfully - presumably (implied Muggeridge) because of Teresa’s divine light. (The cameraman had a different explanation!)

Over the years since then, thousands of mainly British and American young men and women have travelled to Calcutta to serve Mother Teresa’s cause. They were full of enthusiasm to do good to the Indian poor, and most returned home with a life-changing experience. Mother Teresa became a photo-opportunity for celebrities, the rich and the powerful from all over the world, from the Indian painter M. F. Husain and Princess Diana to Senator Edward Kennedy and President Ronald Reagan. Like the pope, she became something of a globetrotter, rubbing shoulders with political and religious leaders, along with some decidedly dubious businessmen. In 1979, she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. At the beginning of the new millennium, despite considerable controversy, the Catholic Church seems determined to canonize her as a contemporary saint who ministered to the humble.

When she died on 5 September 1997 - less than a week after Princess Diana - there was a massive funeral procession in Calcutta organized by the government, with Mother Teresa’s body borne rather inappropriately on a gun carriage. Her order, the Missionaries of Charity, carries on in Calcutta under Sister Nirmala, a timid Hindu convert who has refused to call herself Mother and is reluctant to give interviews. Nor does her institution, Nirmal Hriday, lack inmates: I saw 85 people lying on mattresses during a visit in 2004. But the city whose name Teresa took to herself is distinctly uncomfortable with her glory. Her death anniversary is hardly commemorated although she now has a street named after her. There is a larger-than-life mosaic of her on the wall of the metro station at Kalighat and a small and insignificant bust statue. If you drive around the city, you will most likely see her image only in the form of old and tattered posters with her slogan “Calcutta is my workshop”.

The main reason for discomfort is that Mother Teresa made Calcutta synonymous with poverty and slums in the mind of non-Indians, obliterating all other characteristics of the city, including its artistic life. In other words, her work gave new currency to the colonial notion of the Black Hole of Calcutta and Kipling’s City of Dreadful Night. Secondly, many people who worked at Nirmal Hriday, especially foreign volunteers with medical knowledge, were dismayed by the lack of training available to the helpers - newcomers, for example, might be asked to bathe a leprous woman without receiving advice as to how to protect themselves - and even more by the lack of commitment to scientific medical treatment. Unlike some other Calcutta charities, the Missionaries of Charity did not care to nourish those with malnutrition or to nurse the diseased back to health; Mother Teresa apparently wanted only those who were about to die. Although they would scarcely be treated medically, they would be assured of an afterlife of eternal peace. When none of the city’s hospitals could find space for a dying patient, they knew they could drive the poor soul to Nirmal Hriday in the dead of the night. There the dying person would lie on a foam mattress of green or blue plastic and receive a last rite, however alien it might be.

Furthermore - and here I have much less sympathy for Calcuttans’ criticisms - Mother Teresa and her mission were a disturbing challenge to Calcutta’s administrators, both because of her admirable determination and because she tried in her own way to improve the city. Without doubt she demonstrated how an individual with vision and persistence could draw world attention to a local humanitarian failure. With only five rupees and no training in business, she built a chain of 755 centres throughout the world - no mean feat. The Missionaries of Charity now run some 600 homes of various kinds in 125 countries besides India. Since her death, as with the Ramakrishna Mission, funds and volunteers continue to arrive freely and her name has been copyrighted. But still, if her order wishes to reconnect her name with the city that made her famous in a positive way, it should devote itself to looking after the poor as well as the dying by offering proper medical care. The Missionaries of Charity owe that to Calcutta.

The City in Crisis

The refugees camping in the streets received a subsidy from the government, however small. But the squatters had no means of subsistence. Everyone was forced to take whatever work was on offer simply to survive. The men became casual domestic servants, porters, sweepers, hawkers, rag pickers, and rickshaw pullers; the women became domestic helpers and often turned to prostitution. Others took to petty crime, while still others became goondas. When house owners tried to evict the street dwellers and remove the shacks of bamboo, straw, plywood, cardboard boxes, plastic sheeting, corrugated tin and newspaper that had sprung up on the pavements outside the boundary walls of respectable properties, these menacing goondas would turn up to defend the shanty dwellers and throw bricks through the windows of the houses.

Politically the refugees identified with the left. Bengali intellectuals pre-1947 were already oriented towards Marxism and social revolution (notwithstanding the mass appeal of the fascistically inclined Subhas Chandra Bose). Now millions of ordinary people were destitute and felt they had nothing to lose, so they became easy fodder for agitators. Supported by the left-wing political parties, they became more and more voluble. This was the time when Calcutta’s infrastructure not only became more squalid and crowded, but its walls also became covered in graffiti. The writings on the walls, indeed on any available surface, asked “Why are we here?” and “Are we not humans?” The questions demanded answers. The government of Chief Minister B. C. Roy did not know how to reply.

Most of the refugees had no identity card, passport or ration card. Visible everywhere in the city, officially they were invisible. The undernourished children who saw their first light lying on the pavements of Calcutta quickly became props for an army of beggars. With one arm outstretched, and the other clutching a deformed baby, mothers infested the streets, pestering for alms. Calcutta had never seen persistent and itinerant beggars like these before; hitherto, mendicants had congregated mainly near the temples and mosques and at the cremation grounds by the river.

Bengal Famine, 1943, photographed by Sunil Janah

The refugee invasion was too big for the city - any city - to handle. It scarred Calcutta and Calcuttans. Most residents had some link with East Bengal and felt a natural affinity with Bengali Hindus fleeing Pakistani persecution. As for the central government in Delhi, it did not offer much funding, busy as it was trying to sort out the administrative nightmares of a newly independent country of great complexity. Nor was any help forthcoming from the former colonial masters, occupied with Britain’s own recovery from the Second World War. Calcutta was left alone to pick up the pieces with totally inadequate resources and no experience of coping with disaster on such a scale. No wonder slums multiplied throughout the city with a naked display of human misery, while anger, frustration and desperation unbalanced people’s minds.

The city’s writers and artists responded. Many of them joined the Indian People’s Theatre Association or were sympathetic to it. Founded in 1943 as an anti-fascist group, the IPTA produced and toured plays about the plight of ordinary people, including the refugees. Poets of the time like Samar Sen and Subhash Mukhopadhyay and novelists such as Tarashankar Bandopadhyay and Manik Bandopadhyay wrote about the refugees. The artists Zainul Abedin, Chittaprasad and Adinath Mukherjee painted and sketched them, and the photographer Sunil Janah, who had taken some of the most harrowing photographs of the famine in 1943-44, depicted the refugees in numerous images. The film director Ritwik Ghatak, who came from East Bengal, was deeply moved by their plight and a little later made a poignant melodrama, Subarnarekha, set in a Calcutta refugee colony, using a wonderful new actress, Madhabi Mukherjee, playing a woman forced to sell her body to survive.

Thus the 1940s and after were certainly troubled years for Calcutta, but culturally they were fruitful. In 1952, for example, there was a weeklong All India Peace Conference in Calcutta attended by major artists and intellectuals from all over India including the painter Jamini Roy, the musician Ustad Allauddin Khan, the dancer Uday Shankar and the actor Prithviraj Kapoor. Calcutta also hosted the first international film festival (which included Akira Kurosawa’s new film Rashomon); and the shooting of Satyajit Ray’s first film, the classic Pather Panchali, began. Ray, Ravi Shankar and the actor and theatre director Shambhu Mitra all began their careers during what was a hopeful time in Bengal, artistically speaking. We shall return to all this in Chapter 9.

Under Western Eyes

As Calcutta became a byword for human degradation, it began to attract foreign visitors with a taste for observing such horror. Although many of them could occasionally be intelligent, sensitive and balanced, the general trend of their observations was anything but. Some of their criticism may be excused by their ignorance, but much of it was clearly motivated by arrogance and disdain; they did not bother to do any research on the city, apparently feeling that their uninformed personal impressions had their own raw validity.

Perhaps the most interesting examples are the social anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, the film-maker Louis Malle and the writer and Nobel laureate and former member of the Nazi youth, Günter Grass. LéviStrauss’s Tristes Tropiques (1955), Louis Malle’s Calcutta (1969), a prelude to his series of films Phantom India, and Grass’ two books referring to Calcutta, The Flounder (1977) and Show Your Tongue (1988), have exerted considerable influence on western perceptions of post-colonial Calcutta.

Lévi-Strauss visited the city fairly briefly during the chaotic period of the early 1950s and was overwhelmed with disgust. But in expressing his horror, he shows little awareness of the city’s history and complex culture. His implication is that fundamentally Calcutta has always been like this - for Indian cities are “the urban phenomenon, reduced to its ultimate expression”:

Filth, chaos, promiscuity, congestion; ruins, huts, mud, dirt; dung, urine, pus, humours, secretions and running sores: all the things against which we expect urban life to give us organised protection, all the things we hate and guard against at such great cost, all these by-products of cohabitation do not set any limitation on it [i.e. the urban phenomenon] in India. They are more like a natural environment, which the Indian town needs in order to prosper. To every individual, any street, footpath or alley affords a home, where he can sit, sleep, and even pick up his food straight from the glutinous filth. Far from repelling him, this filth acquires a kind of domestic status through having been exuded, excreted, trampled on and handled by so many men.

Lévi-Strauss saw the interaction of these individuals with himself as equally atavistic:

Every time I emerged from my hotel in Calcutta, which was besieged by cows and had vultures perched on its window-sills, I became the central figure in a ballet which would have seemed funny to me, had it not been so pathetic. The various accomplished performers made their entries in turn: a shoeblack flung himself at my feet; a small boy rushed up to me; whining ‘One anna, papa, one anna!’ a cripple displayed his stumps, having bared himself to give a better view; a pander - ‘British girls, very nice...’; a clarinet-seller; a New Market porter begged me to buy everything, not because he himself could get any commission but because the annas he earned by following me would allow him to eat.

After mentioning “a whole host of minor players”, such as rickshaw touts, shop keepers and street hawkers, Lévi-Strauss concludes that in the “grotesque gestures and contorted movements” of the ballet, he was witnessing the “clinical symptoms of a life-and-death struggle”:

A single obsession, hunger, prompts this despairing behaviour; it is the same obsession which drives the country dwellers into the cities and has caused Calcutta’s population to leap from two to five millions in the space of a few years; it crowds refugees into stations, although they cannot afford to board the trains, and, as one passes through at night, one can see them sleeping on the platforms, wrapped in the white cotton fabric which today is their garment but tomorrow will be their shroud...

But this conclusion is simply wrong, however poetic its morbid imagery. Hunger was indeed what drove people into Calcutta during the famine in 1943-44, but it was history and politics, not hunger, that drove them there in greater numbers post-1947. By conflating the famine and the partition into one episode, Lévi-Strauss reduces Bengal and Calcutta to a primitive stereotype in which individual behaviour plays no part. No wonder that he took no interest in the work of that great Bengali individualist, Satyajit Ray, whose film about the famine, Distant Thunder, humanized the catastrophe by focusing on a handful of individuals, and whose last film, The Stranger, about an anthropologist, was ironically enough based partly on the anthropological works of Lévi-Strauss.

Louis Malle and Günter Grass: Images of Horror

I saw Louis Malle’s Calcutta when it was first shown in 1975, along with his seven-part Phantom India, to a packed London audience, following the sensational banning of the entire documentary in India. The Calcutta film struck me as a collage of random repulsive images: pigs snuffling in a sewer while slum children are at play; dying people at Mother Teresa’s Nirmal Hriday; buses packed with people like sardines while others cling to the doors and windows like crabs; a cripple sitting in the middle of a public thoroughfare while traffic dodges around him; a leper with rotting flesh; and much more. Relentlessly the camera rolls and captures scenes shockingly at odds with normal life in a developed western metropolis. Who gave Malle the right to do this? And what was his purpose? I was confused and helplessly enraged by his Calcutta film.

Much later I read a letter written at the time by Satyajit Ray to Marie Seton, his first biographer, which clarified for me what was wrong with Malle’s attitude. Ray had talked to Malle at length in Calcutta in 1967 and showed him some of his own work, but he was unsympathetic to the French director’s whole approach to India, described by Malle as “the perfect tabula rasa: it was like starting from scratch.” In Ray’s view:

The whole Malle affair is deplorable. Personally I don’t think any director has any right to go to a foreign country and make a documentary film about it unless a) he is absolutely thorough in his groundwork on all aspects of the country - historical, social, religious etc., and b) he does it with genuine love. Working in a dazed state - whether of admiration or disgust - can produce nothing of any value.

There is a story told in Calcutta that while Malle was busy shooting a demonstration in Calcutta, an infuriated Bengali policeman came up and threatened to smash his camera, shouting “Who do you think you are?” On hearing the name “Louis Malle”, the policeman smiled, said “Zazie dans le Metro!” and left Malle alone to work. The encounter is typical of a city in which ordinary people sometimes spring a surprise with their lovingly garnered knowledge of western cultural life. But Malle’s film, with its preoccupation with the exotic and the bizarre, fails to capture Calcutta’s genuine aspiration towards art and culture as a response to harsh realities. Malle was explicitly distrustful of “westernized” Bengalis, and deliberately excluded Bengali artists and thinkers from his film; not even Mrinal Sen (who joined Malle in at least one of his shoots) is permitted a voice. Hence the fact that the film amounts to “nothing of any value”, as Ray perceived, despite western acclaim for the documentary’s truthfulness. Once again, as with Lévi-Strauss, history and perspective are signally absent. Indeed, it is very much as if Malle had taken Lévi-Strauss’s fascination with Calcutta’s filth and grotesquerie and set out to illustrate them on film.

For Günter Grass, too, the place is, finally, an embarrassment to civilization. His first visit was in 1975 as a state guest staying at the Raj Bhavan. He visited Nirmal Hriday but did not meet Mother Teresa, went to one of her leper colonies, saw the Kalighat temple, visited the Ramakrishna Mission at Narendrapur and its cultural institute at Gol Park, and met writers, artists and intellectuals, including Sen but not Ray. Then he went home and wrote a novel, The Flounder, which contains a section on Calcutta, “Vasco returns”, in which Grass’ alter ego Vasco (named after Vasco da Gama, the fifteenth-century Portuguese explorer), visits India.

Here is Vasco’s view of a Bengali writers’ group:

They read one another (in English) poems about flowers, monsoon clouds, and the elephant-headed god, Ganesha. An English lady (in a sari) lisps impressions on her travels in India. Some forty people in elegant, spacious garments sit spiritually on fibre mats under a draftpropelled fan; outside the windows, the bustees [slums] are not far away.

Vasco admires the fine editions of books, the literary chitchat, the imported pop posters. Like everyone else he nibbles pine nuts and doesn’t know which of the lady poets he would like to fuck if the opportunity presented itself.

Why not a poem about a pile of shit that God dropped and named Calcutta.

Apparently the writers’ sophistication vexed Grass. Like Malle (and Lord Curzon before him), he perhaps presumed that the middle-class babus and their women were deliberately out of touch with the realities of Calcutta. When writing of his meeting with Mrinal Sen, Vasco casually ponders: “In 1943... two million Bengalis had starved because the British army had used up all the rice stocks in the war against Japan. Had a film been made about it? No, unfortunately not. You can’t film starvation.” If we leave aside the simplistic economics, Grass was obviously ignorant of Sen’s own film on the famine, not to speak of Ray’s celebrated famine film, which won the top prize at the Berlin Film Festival in 1973.

Yet Grass was moved by the “cheerfulness” of the poor in spite of their misery. They prompt Vasco to make a highly emotional statement:

Send a postcard with regards from Calcutta. See Calcutta and go on living. Meet your Damascus in Calcutta. As alive as Calcutta. Chop off your cock in Calcutta (in the temple of Kali, where young goats are sacrificed and a tree is hung with wishing stones that cry out for children, more and more children)... Recommend Calcutta to a young couple as a good place to visit on their honeymoon. Write a poem called “Calcutta” and stop taking planes to far-off places. Get a composer to set all the projects for cleaning up Calcutta to music and have the resulting oratorio (sung by a Bach society) open in Calcutta. Develop a new dialectic from Calcutta’s contradictions. Transfer the UN to Calcutta.

But his final line about Calcutta makes all this sound merely like delirious babble: “Let’s not waste another word on Calcutta. Delete Calcutta from all guidebooks.”

Having ignored his own advice, Grass visited the city again in 1986-87, now with his wife Ute, arriving with the professed intention of settling down in the place for a year to observe, write and draw (though in fact the pair stayed only for six months). They rented a garden bungalow in Baruipur within commuting distance of the south of the city. From there they used public transport, including man-pulled rickshaws, to move about, and experienced heat, humidity, grime, mosquitoes and officialdom at first hand. Ute Grass shopped, cooked and knitted. Her husband took notes and sketched, and also visited places away from the city such as Tagore’s university at Shantiniketan. Later, when commuting fazed them, they moved to a small flat in Lake Town.

While in Calcutta, apart from being taken for Graham Greene, Grass toured a red-light district under covert police protection, visited burnt-out slum dwellers, entered a crumbling Marwari house in Barabazar, and watched the potters of Kumortuli at work. Militant young Muslims mobbed him and his wife at Metiaburz near Garden Reach when they went to visit the place of exile of Wajid Ali Shah, the last nawab of Oudh, who left Lucknow and settled in Calcutta after he was deposed by the British in 1856. At the Victoria Memorial, he was unimpressed by the haphazard displays, and during Durga Puja he was outraged by the lavishness. He was also bored by the famous Bollywood blockbuster Sholay, which he saw for an hour at a local picture house. His play, The Plebeians Rehearse the Uprising, was staged but he was disappointed at the lack of response. But when he visited the Calcutta Social Project at Dhapa, which educates the municipal dump’s child rag pickers, he was impressed. He dedicated his book on Calcutta, Show Your Tongue, to the project and its organizers Mr. and Mrs. Karlekar. (He continues to send donations to this project and keeps in touch through emails with people associated with it.) There was time, on this second visit, and freedom, since he was not a state guest, for Grass to have peeped into the heart of the city and to have talked with some genuinely creative people. But, once again, he strangely avoided Satyajit Ray, despite Ray’s having made many trenchant and pessimistic films about Calcutta which might have been expected to interest a political radical like Grass. Films such as Pratidwandi (The Adversary), Seemabaddha (Company Limited) and Jana Aranya (The Middle Man), which, to quote Andrew Robinson’s biography of Ray, The Inner Eye (2003):

depict, through the world of work, the stress of Calcutta living on young educated men at a time when this had never been more intense: the rise of revolutionary terrorism and massive government repression, followed by the Bangladesh war and refugee crisis, corruption and nationwide Emergency, leading eventually to the emergence of the Communist government that ruled Bengal in the 1980s.

Grass even did his best to avoid the presence of Tagore, despite visiting Shantiniketan. When at a meeting with Bengali poets, somebody opined that Grass might soon receive the Nobel prize, he tetchily responded: “To you the Nobel prize means the climax of literary achievement because your greatest poet Rabindranath Tagore, had won it. To me however it is not all that important.” Another time he told a Bengali woman friend: “Your first and last word is Rabindranath. You are unable to go beyond him. By ‘literature’ you only mean Rabindranath. That is your limitation.” Fair enough as a reaction to Bengali provincial vanity about Tagore - but not at all an adequate response from a major writer wishing to know Calcutta. The fact is that both Tagore and Ray are demanding artists (as we shall see in Chapter 9) and Grass was unprepared to take them on. He learned no Bengali - when Bengali authors presented him with their works he would curtly refuse, saying “What shall I do with them? Do I have to learn Bengali now?” - but even without bothering with the language, he made little effort to comprehend the city’s finest artistic products.

The outcome was a trite and inconsequential book, packed with his own oppressive scribbled drawings, illustrating a relatively short, incoherent text with significant factual errors. One might have expected that in revisiting a place he disliked first time around, Grass would have cultivated his knowledge and understanding of it. But reading Show Your Tongue, Grass’ Indian interviews, and the memoirs of people who met him (recently published as My Broken Love: Günter Grass in India and Bangladesh), the impression is similar to that given by Lévi-Strauss and Malle: that Grass, too, wanted to gratify his curiosity about human degradation in Calcutta’s slums and streets. Sadly, none of these three talented Europeans shows any sustained interest in Bengali “high” culture, apparently regarding it as enfeebled by western influences. All three sought to reinforce the idea of the “otherness” of the East, and did not feel it worth their while to move beyond their immediate sensory experience.

The Rise of the Left

When Lévi-Strauss visited Calcutta in the 1950s, the city was ruled by the Congress Party under B. C. Roy. By the time of the mass demonstrations filmed by Louis Malle in 1968, the Congress was being forced to give way to communist parties. In the 1970s, these parties came to dominate Bengal politically; by the time of Grass’ second visit in the 1980s, the Left Front was entrenched in power.

There were two chief reasons for the left’s success. First, the Bengali intelligentsia, which dominated the political life of Calcutta to the almost total exclusion of the business communities (Marwaris, Punjabis, Chinese, Armenians and so on), had long favoured left-wing ideology of the Soviet variety, with an accompanying distrust of commerce. The businessmen, for their part, had done well out of the city, but had invested little in return (unlike in Bombay). The distrust between the Bengali babus in charge of politics and the people running the city’s economy was peculiarly destructive of good civic governance.

Second, of course, there was Calcutta’s unique refugee predicament. The central government failed to grant a budget appropriate for dealing with the enormity of the city’s population problem, and so civic conditions deteriorated from bad to worse after 1947. By 1966, there were estimated to be about 400,000 slum dwellings in and around the city with inadequate water supplies and sanitation. Their occupants were naturally inclined to vote for political parties of the radical left.

In spite of the slums, peasants from the surrounding rural areas continued to enter Calcutta to escape the declining agricultural conditions in the rest of West Bengal. Unable to find employment, these unskilled people often fell in with criminals and shady dealers and reinvented themselves as contract henchmen for dishonest businessmen and dubious political groups. As a lumpenproletariat involved in various protection rackets, they could be hired to break strikes, sabotage picket lines or infiltrate a political march and turn it into mayhem. Uprooted and unemployed, they were a destructive force without scruples. Their disaffection was further exacerbated by the new rich of the city and the culture of consumerism that was evolving to satisfy the wealthy minority’s growing needs. Smart hotels and fancy houses were being built in expensive areas of the city like Alipur, while most of the population was barely surviving. The gap between the rich and the poor became so blatant in the 1960s that the situation was explosive.

At the beginning of 1967, due to drought, India yet again faced a food shortage of about ten million tons. There were repercussions in Calcutta’s industrial sector: high food prices compelled people to refrain from buying consumer goods, which hit production and increased unemployment. Between January and March that year, over 23,000 workers were laid off in 95 industrial establishments. In elections the Congress government was finally toppled in Bengal, and replaced in February by a shaky coalition of breakaway Congress groups allied with two communist factions, one pro-Soviet Union the other pro-China. The communists’ priority, as soon as they came to power, was to entrench themselves rather than trying to govern. At the beginning the communists achieved some minor successes by reducing taxes on slums and by rehabilitating some refugees. In rural areas, using politically active volunteers, the pro-China party legalized a land-grab procedure to reduce landlords’ large holdings. A procession chanting “Mao Tse Tung Zindabad!” (Long Live Mao Tse Tung!) would arrive at a targeted plot and mark its four corners with red flags, declaring the land to be the property of the citizens’ committee. As a result, the party managed to increase its peasant membership by 450,000 in West Bengal.

Against such a background of political and social upheaval, a small peasant uprising in May 1967 at a small place known as Naxalbari created a volcanic impact in Bengal and added a new word to the vocabulary of revolution - Naxalite. Naxalbari is near Darjeeling at the northeastern tip of India, on a strip of land between Nepal and East Pakistan (now Bangladesh). The country is hilly with tea gardens and dense forest and its tribal population has some reputation for insurrection. In Calcutta, the Naxalbari uprising was perceived as the action of desperate peasants taking up bows and arrows to fight the police and oppressive landlords. Although crushed within a few months, it set the educated youth of Calcutta aflame. The students of Presidency College created a poster celebrating Naxalbari, and soon the city was plastered with posters shouting “Naxalbari Zindabad!” Peking Radio immediately reported a great people’s revolution in Bengal and predicted that the Indian masses would proceed along the path pointed out by the Great Helmsman Mao.

Like the revolutionaries of the Swadeshi movement half a century before, most of the Calcutta Naxalites were young, clever and idealistic students, from relatively well-off progressive middle-class families. Abandoning the security and comfort of home, metropolis and secure career prospects, many went to the villages for months to work among the peasants as Red Guards. To begin with they found the rural existence trying but they gradually won the trust of the villagers and politicized many in favour of armed revolution. Others went to work among the city’s industrial slums, taking new identities to avoid police persecution and remaining out of contact with their families for long periods. Both groups were appalled by the poverty and squalor they encountered in the villages and in the slums, and felt increasingly militant. Working in secret at grassroots level, they started to build a movement to overthrow the establishment.

Many older Bengalis had a degree of sympathy with the young radicals. Satyajit Ray, for instance, shows us a young revolutionary in Pratidwandi, which was filmed at the height of the movement in 1970, who is intelligent and decisive but fundamentally one-track minded, unable to understand his elder brother’s scruples about violence. When V. S. Naipaul interviewed at length a former Naxalite, who had been a student of physics at Presidency College in the mid-1960s, in India: A Million Mutinies Now (1990), the man recalled:

Many of the comrades before had succeeded in forming squads and carrying out annihilations, mainly in the area covered by the old uprising... Indians are basically a very violent people. I was doing Red Guard Action in new areas, and in spite of my best efforts I could not persuade the peasants to carry out a single annihilation - which was a cause of great remorse to me, and led to a feeling of inadequacy.

He had not recanted his belief in violence but added, when pressed by Naipaul, that the “major mistake” of the Naxalites had been to accept the Marxist position that the intellectuals could lead the revolution: “I feel the people must liberate themselves. The intellectuals can only hand them the equipment for doing so.”

It took two or three years before the violence in the countryside was unleashed in Calcutta itself. Superficially, in 1967-69, the city remained calm, apart from noisy street demonstrations. In Park Street and Chowringhee life remained as easygoing as before, as remembered by Sumanta Banerjee in his chronicle, In the Wake of Naxalbari (1980):

Swanky business executives and thriving journalists, film stars and art critics, smugglers and touts, chic society dames and jet-set teenagers thronged the bars and discotheques. All mention of the rural uprising in these crowds was considered distinctly in bad taste, although the term ‘Naxalite’ had assumed an aura of the exotic and was being used to dramatise all sorts of sensationalism in these circles - ranging from good-natured Bohemianism to Hippy-style pot sessions.

But in 1970, the city once more became violently disturbed. The economy was collapsing because of trade-union militancy and factory lockouts, the unwillingness of business to invest in West Bengal, and the reluctance of a “people’s government” to use the police to restore order. As film director Ray commented, with unusual despair, in an article published in February:

Here, while a shot is being taken, one holds one’s breath for fear the lights might go down in the middle of the shot, either of their own accord, or through a drop in the voltage; one holds one’s breath while the camera rolls on the trolley, lest the wheels encounter a pothole on the studio floor and wobble - thus ruining the shot; one holds one’s breath on location in fear of a crowd emerging out of the blue...

One of those directing the agitation was Charu Majumdar (1918-72). The clever son of a landlord from Naxalbari, he joined the pro-Soviet Communist Party of India in 1938 and worked tirelessly for it. But in 1969 he split from the party and on Lenin’s birth anniversary formed the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist), which he launched on May Day at one of the seething public meetings on the Maidan that were a feature of Calcutta life in those days. Later he coined the notorious slogan, “China’s chairman is our chairman.” Soon Majumdar ordered his Naxalite followers to kill policemen and informers in broad daylight, along with small businessmen, government officials, and college teachers, which led to the murder of a vice-chancellor by a young boy. For the next year or so the city was an arena for guerrilla warfare. The goondas took advantage of the situation and in the name of political activism started to vandalize and loot anything that could be interpreted as being part of the establishment. They also disposed of opposition gang members under cover of political assassinations. Predictably, the government was soon blaming all anti-social acts on the Naxalites.

Almost every day there were massive disturbances on the streets. Bomb blasts were a constant background to ordinary life - in public places but also in private homes when terrorist experiments went wrong. Cinema halls and theatres were torched by hooligans, who wrecked the racecourse and began attacking foreigners: British, West German and French embassy officials all suffered. As robbery and mugging reached a peak, many left the city. Incapable of controlling such unbridled vandalism, and unable to get the political leaders to cease fighting each other, the governor of West Bengal suspended the state’s Constituent Assembly and asked the central government to send in the army, as had happened under the British during the 1930s.

For a year and more, the military took over parts of Calcutta with orders to shoot to kill. Ordinary citizens were obliged to raise their hands over their heads simply to cross the road. Sumanta Banerjee again:

Clumps of heavy, brutish-faced men, whose hips bulged with hidden revolvers or daggers, and whose little eyes looked mingled with ferocity and servility like bulldogs, prowled the street corners. Police informers, scabs, professional assassins, and various other sorts of bodyguard of private property stalked around bullying the citizens. Streets were littered with bodies of young men riddled with bullets.

During “combing operations” the army would often kill Naxalite suspects on the spot; others were beaten to death in prison. Between March 1970 and August 1971 the official death toll of Communist Party (MarxistLeninist) members was 1,783, but historians think this figure should be at least doubled. After the movement had died down in Calcutta in late 1971, many of the Naxalites in prison were granted an amnesty and in some cases inducements for rehabilitation; the activist interviewed by Naipaul agreed to go to London to do a Ph.D in physics (he was accompanied right up to the aircraft at Dum Dum by police). Today Naxalbari itself is quiet again, languishing in neglect along with its busts of Lenin, Stalin and Charu Majumdar.

But Calcutta’s agony was not yet over. During the second half of 1971, there was a new influx of refugees running from torture, rape and death at the hands of West Pakistani soldiers during the bloody birth of Bangladesh. Once again, as in 1947, refugee colonies had to be established. The civic amenities could not stand the strain; the slums mushroomed, there were constant power shortages, garbage mounted in the streets, and the water supply became seriously polluted. Hundreds of thousands of graduates, many with good degrees, were unable to find work, even as clerks. For a while, during the early 1970s, it seemed as if Calcutta would become completely dysfunctional.

Marxism Calcutta-style

When the Left Front took over in 1977, there were a few improvements in basic services, at least to begin with, but Calcutta’s general economic stagnation continued. An ingrained absence of work ethic in government and the public services, combined with a carefully cultivated romantic notion about revolution in the general population, is a poor recipe for progress. By voting in the Left Front throughout the 1980s and 1990s - despite the collapse of the Soviet Union and its satellites - Calcuttans performed their sole political duty. Many voters liked the government’s Marxist ideology, others knew that it would be sympathetic to strike action, which meant time off from work; and anyway there were no serious alternative parties in Bengal. But the poor labour relations under the Left Front drove industries and foreign investment away from the city - so much so that the long-running chief minister, Jyoti Basu, had to spend much time abroad in the 1990s trying to make West Bengal attractive to foreign capitalists. (Of course, his all-expenses-paid trips to London, New York and other commercial capitals came from state funds.)

The Left Front claimed to have intellectual and cultural aspirations, but their policies delivered little. Serious academics, especially scientists, have increasingly deserted Calcutta for other parts of India with a more creative and congenial intellectual atmosphere and better facilities. In the 1950s, the state government had supported some good work in the arts, such as funding Satyajit Ray’s first film Pather Panchali and giving land for the Academy of Fine Arts building in Cathedral Road. But apart from building a major cinematheque, known as Nandan, in central Calcutta, the Rupayan film technology studio at Salt Lake in the 1980s, and the sports complex in Salt Lake in the 1990s, the Left Front government did little else to promote the city’s culture other than changing street and place (and city!) names for reasons of political correctness. Now the government is even debating the idea of changing the name of the state from West Bengal to Bangla. Cultural icons like Tagore and (later) Ray have been liberally cited as evidence of Calcutta’s international importance, but most Left Front ministers, including Basu himself, have revealed themselves to be embarrassingly ignorant of Tagore’s and Ray’s actual works. (It took the National Film Theatre in London, not Calcutta’s Nandan, to stage the first complete retrospective of Ray’s films, in 2002.)

Salt Lake City and the Metro

Yet even as it decays, Calcutta renews itself. The 1970s saw the beginning of an entirely new middle-class housing development to the east of the city. The project was inspired by the chief minister B. C. Roy, who launched it officially just before he stepped down in 1962, whereupon it was named after him: Bidhan Nagar. The concept - which appeared quite radical at the time - was to extend the city by filling up low-lying land in two swampy expanses known as the northern and southern salt lakes, beginning with twenty square miles of the northern part of the lake that lies close to the city. A Yugoslav contractor filled the salt lakes by ingeniously pumping silt dredged from the Hugli River. The pumps worked almost constantly for nine months. In the process, they not only reclaimed the land but also improved the navigability of the river.

This is the place where in the 1970s at a rudimentary rehabilitation centre for refugees from Bangladesh, Senator Edward Kennedy spotted one of Mother Teresa’s nuns, Sister Agnes, washing the clothes of a cholera patient and wanted to shake her hand. When she said her hands were dirty, he replied: “The dirtier they are the more honoured I am.”

Salt Lake is a project that has been well planned from the start. The area was divided into five sectors, of which the first three are residential and the last two industrial and commercial. The residential plots were deliberately kept small so that the middle-income group could afford them; and there are height restrictions on the buildings to avoid vertical congestion. Water supply, sewerage, drainage, population density and road space were all conceived together, and the result is a pleasant and clean environment with good amenities for shopping, sports, health and education, and good transport connections to the airport and the city. The biggest sports stadium in India, the 120,000-seater Yuva Bharati Krirangan, is close by, and next to it is the Netaji Subhas National Institute of Sports, a forty-five-acre sports centre with modern training facilities and a boating lake. There are good modern hotels, too, because of the airport location, although Calcutta’s best hotel, the Taj Bengal, remains tucked away in Alipur. But all this means that since the 1980s, property prices have rocketed beyond the means of middle-income earners; Salt Lake becomes year by year more like a suburb for the wealthy with designer houses set beside tree-lined spacious roads. Also, the area between it and the city is fast developing with new industries, including electronics and chemical plants. But in spite of creeping urbanization, in the roadside ponds of brackish water along the Eastern Bypass you can still spot birds such as cormorants, little grebes and herons, and animals like otters and jackals and even, if you are lucky, a rare marsh mongoose. In spite of dense urbanization, the suburbs of Calcutta have a thriving bird population.

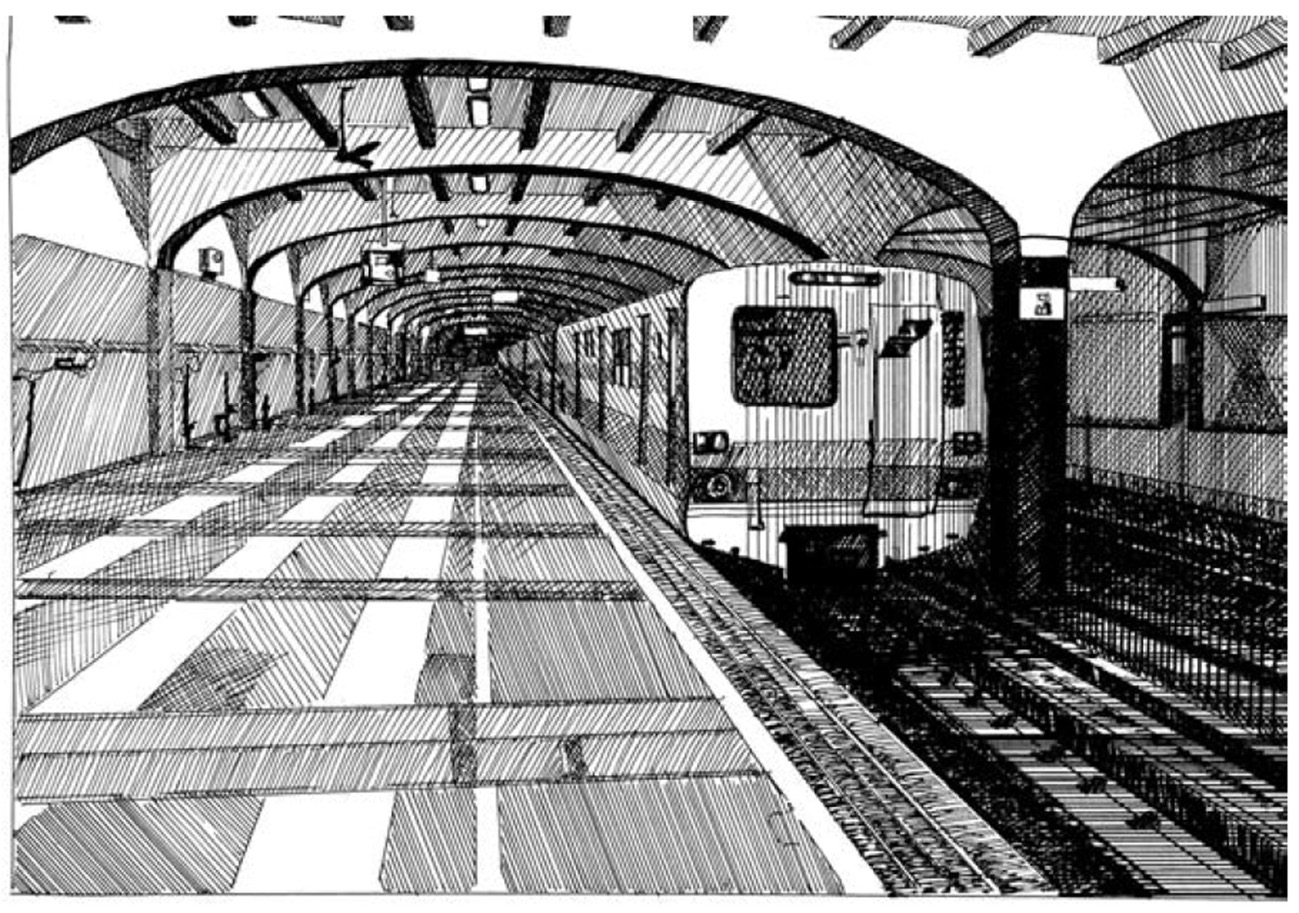

The Calcutta Metro is a success story too. But when its construction began in the 1970s, there was considerable scepticism from Calcuttans. For a start, the idea of an underground railway in a city built on a swamp is difficult to credit. Then there is the endemic problem of monsoon flooding. And what about the city’s hordes of pavement dwellers? Surely they would simply move underground and clog the system. Most people were pessimistic - and became more so as the seemingly endless digging rendered the city’s main thoroughfares, such as Ashutosh Mukherjee Road in the south and Chittaranjan Avenue in the north, almost impassable for well over ten years. I recall a wall poster likening the Metro project to the story in The Ramayana of King Ravana who conceived the impossible idea of building a staircase from the earth to heaven. The poster designer jokingly asked “Patal rail ki Ravaner sinri?” (“Is the underground rail Ravana’s steps?”) After twelve long years of disruption - massive holes in the streets, all-day traffic snarls, defunct telephone connections, dirt, dust and noise - the first stretch (only a handful of stations between Bhabanipur and Maidan) opened in 1984. Another eleven years later, in 1995, the line from Dum Dum to Tollygunj was complete. Soon travelling by Metro caught on and people became proud of the Metro.

The system is clean, efficient, cheap and comfortable - worth a joy ride. As you descend, you leave behind the chaos of the streets with dangerously overcrowded buses, taxis, lorries, scooters, rickshaws and many other forms of transport, along with teeming crowds, and suddenly enter an orderly environment. The ten-mile journey from Dum Dum to Tollygunj, which can occupy several sweaty and irritable hours above ground during the rush hour, is done by Metro in 33 cool and clean minutes for under ten rupees; and trains arrive at intervals of less than ten minutes. Calcutta Metro is now being extended southward six more stations to Garia. Also, a further east-west link is under consideration. Neither monsoon flooding nor the homeless nor the graffiti writers have managed to spoil the Metro system. At Rabindra Sadan station you even have the added bonus of some attractive blow-ups of Tagore poetry in his own handwriting.