BOOKS AND JOURNALS

The written word is the obvious, and easiest, place to start when exploring local history, if only to see what has already been written on the subject. Local history books have been written for centuries and are very variable in quality. These books will certainly not mention your ancestor by name unless they played a particularly prominent part in the development of the locality in question. However, they do provide information about how a place changed over time, who the major personalities were and the significant events that occurred there; or at least those selected by the author for inclusion. Unless a book is extremely large or the district chosen is very small, then the author must choose very carefully what he is to include and their priorities may not be the same as all their readers. It is well worth reading some or preferably all of the books written about a locality that your ancestors lived in.

Books are secondary sources; the majority were not written at the time of the events that the author is describing. They are therefore a synthesis and a selection of information chosen by the author. Often they indicate what is known about a topic but it is not the entirety of the potential information. They should be used as guides but not as definitive.

The collections of books held in local studies centres will vary considerably; some may not be books proper, but journals. The books may well date from the seventeenth century to the early twenty-first. Not all may be books as we often think of them, i.e. mass-produced by a publisher and then sold in local shops, but may be unpublished theses, typescripts or even manuscripts.

The advantage of published books is that they will have been read by more than one person and revised accordingly. The author may well have asked friends/colleagues and family to have read through the work for readability and grammar as well as factual content. The editor of the company will also have employed someone to have read it and they will have queried anything which looks ‘odd’ for whatever reason. The author will then have revised the text accordingly.

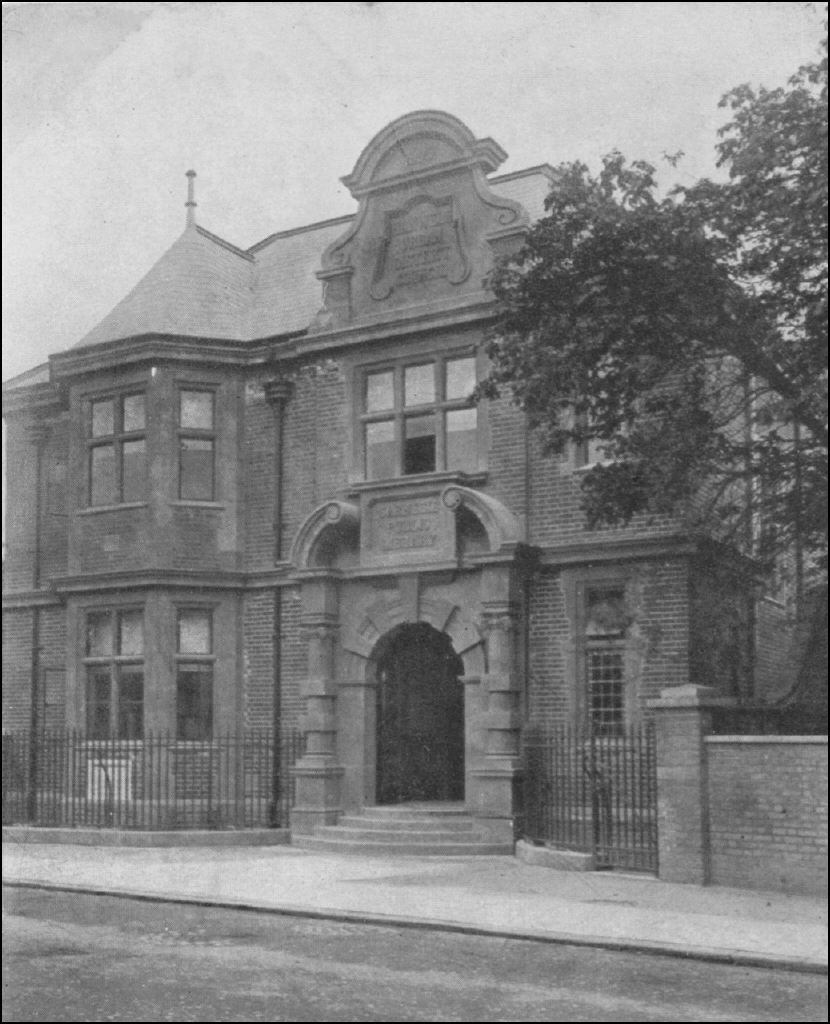

Hanwell Library, 1905. (Paul Lang)

Books gathered together in a record office will include books specifically about the towns and villages that make up that office’s jurisdiction. These are straightforward enough; clearly the ones relating to places associated with one’s ancestors should be consulted. There will also be far more specific books. These may include books on particular schools, churches, businesses and other institutions which have existed in that locality. These are only of obvious use if one’s ancestors had some connection with that place. Likewise there will probably be books about a district’s transport or the locality during a time of conflict (especially the World Wars). These may be of no interest at all; but if your ancestors lived through the troubled times chronicled therein or if they were employed in the transport industry, then these books will provide background information about their lives. Some books may attempt a history of the whole county in which your ancestors lived. Books on a locality’s famous people, or published memoirs/diaries and letters by former inhabitants may be of use, especially if your ancestors were connected to them, perhaps by way of employment or living in the same place at the same time as they did, so even if there is not any direct reference to them, the books may provide valuable context.

Some aspects of local history are relatively obscure and are the product of the interests of a local historian. Writings on these may well never have been meant for a wide audience or may not have been deemed of sufficient commercial worth for a publisher to be interested in them. Although Dr Johnson once wrote ‘No man but a blockhead ever wrote except for money’, this is not a sentiment often cited by local historians for whom there is more to writing than making a profit.

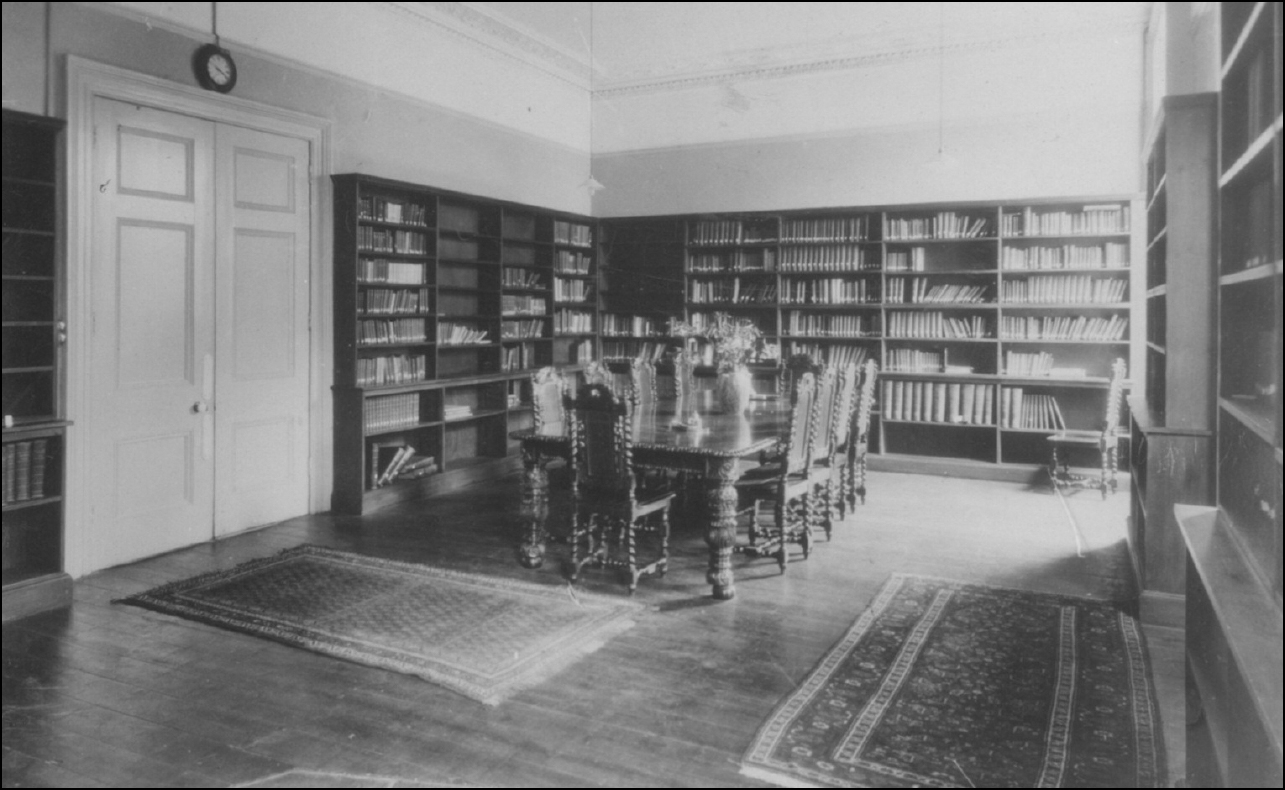

Library of Ealing and Notting Hill Girls’ School. (Paul Lang)

Local history libraries often contain a number of typescripts or even manuscripts (the widespread use of computers has now thankfully made the latter relatively few) written by local historians. There is no qualification needed to be a local historian (local newspapers often use the term most indiscriminately). Some may be barely educated enthusiasts; others may be retired academics well used to research and writing. This is not to say that the products of the former will necessarily be inferior to those of the latter, of course. Local historians will often focus on a particular topic – I have met individuals whose interests include park railings, municipal toilets, clay pipes and bricks. The majority of unpublished works will not be of interest to all family historians but some will be. If your ancestor was employed in the clay pipe or brick works or as a parks or lavatory employee, those just mentioned are of obvious interest.

Don’t forget that out-of-copyright books (mostly those published up to the early twentieth century) are often available online either for free, or hard copy can be bought fairly cheaply as they are print on demand books. If you are searching for such a book, do try searching for it online first.

We should also remember the products of academia which do not appear in journals or as books. In fact most academic theses, both undergraduate and postgraduate, will not be published. These theses are, or should be, the products of original research, written to satisfy the needs of a degree course, or far more substantial and rigorous (and larger), a doctoral thesis. Many cover national or international history (often political or military) but some will cover local history, often connected to a wider topic, for example, witchcraft in seventeenth-century Essex or Jacobitism in the northeast of England.

Other important parts of all these written works are the bibliography and the less common (except in academic theses) footnotes. As with indexes, these vary considerably in their being comprehensive. But they should at least provide a guide to suggested further reading, to primary as well as secondary sources, and these could lead onto other relevant sources of information.

One snag to be careful about when consulting books about local history is the prevalence of urban myth. Information in antiquarian histories is not always sourced, for example, and some authors have uncritically copied from these. Thus stories of doubtful provenance are repeated and gain credence by repetition and so become accepted as fact. That history does not repeat itself but ‘historians’ do is a dictum worth remembering. These tales often revolve around a famous or notorious character or about dramatic events such as plague and war or ghosts. For instance, a commonly believed story is that the Earl of Derwentwater, a Jacobite nobleman beheaded in 1716 for rebellion, was buried in Acton, Middlesex (there was a Derwentwater House there and there is still an obelisk to his memory in the park). In fact the peer never set foot in the place, alive or dead, and both house and obelisk postdate his death by over a century. It is a good story but alas, untrue, so as Indiana Jones is warned in the third film, ‘Trust no one’. He fails to heed this excellent advice, but the historian must be wary. Only trust material which is backed up by evidence; if it sounds fantastic, it usually is.

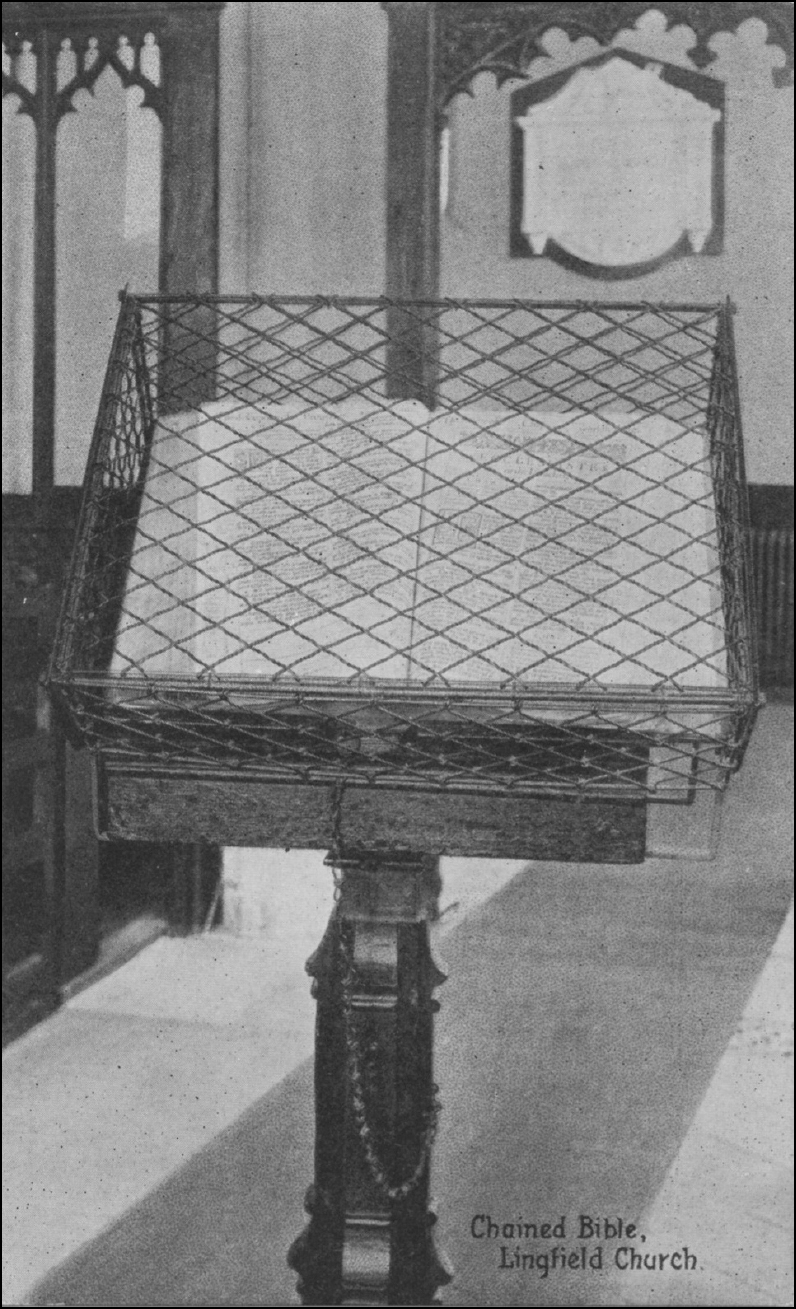

Chained Library, Lingfield Church. (Paul Lang)

Other books were published at the time of the events they describe, for example, the annual reports of the Medical Officer of Health. This post was required by law from the nineteenth to the twentieth centuries and was a local government appointment of a qualified medical professional, initially at a time when public health was seen as imperative by the government. Each year they had to produce a report, often 20–30 pages long, for the local authority in question. This would cover all the topics which might have an influence on the locality’s health, from food standards, gypsy encampments, housing, schooling, pollution in the air or water and even comments on public transport and on aspects of the World Wars. There are statistical tables of deaths in the locality for the previous year, listing how many people (divided by sex) have died and from what cause. Causes are broken down by types of disease/ailment, as well as accidents, suicides, murders and, in wartime, death by enemy action. These are especially worth checking for the years in which your ancestors died in order to see how commonplace (or not) was the cause of your ancestors’ deaths. If it was a death from a disease that was prevalent at that time and in that place, then the medical officer would almost certainly comment upon it elsewhere in his report and perhaps mention what steps were being taken to tackle its causes. Many such reports for London from 1848 to 1972 are available online at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine, at http://wellcomelibrary.org/moh/reports. They can be searched by keyword (e.g. street or disease), year and borough.

One example is the Annual Report for the Local Board of Acton for 1888. We learn that the birth rate was 33.1 and death rate was 13.9, both per 1,000 residents. However, infant mortality was high; of 306 deaths, 113 were under one year (these are also given by street; nine babies died on Acton Green) and 155 under 5. Eleven deaths were by violence (10 accidents, one suicide) and figures give deaths from a variety of diseases and other ailments. There is also a discussion of the various causes of deaths.

Journals are akin to magazines, and are produced by organisations; commercial, charitable, scholarly, clubs, civic, political and religious being the major categories. They are designed primarily for their members and are not always available commercially at time of release. They will tend to represent the official views of that organisation, though there is not always a ‘party line’ to be adhered to. They tend to date from the nineteenth century onwards, but most will be from the twentieth century, and still exist, often in electronic format in more recent times. They appear at regular intervals, some monthly, some quarterly and some annually.

The obvious run of journals to be found are those of historical/antiquarian/archaeological societies which have a geographical connection to the district in which the library or record office is located. For instance, Archaelogia Aeliana, which has covered Northumberland historical topics since the early nineteenth century, should be found at Newcastle Central Library, at the City Archives and at the county record office. Clearly it would not be found on the shelves of the Centre for Kentish Studies at Maidstone (that would be Archaeolgia Cantiana). However, most of these county journals will be located at the National Archives Library and the British Library.

In the nineteenth century, gentlemen and clergy who were interested in their county’s past began to meet regularly and discuss their mutual interests. Members would give talks to their fellows at meetings based on their recent researches and discoveries. Often these concerned artefacts dug up from the ground. Archives also provided material for these ‘papers’ and these talks would appear, often in modified forms, in these journals, so the fruits of research would be preserved for posterity.

The articles published are myriad indeed and limited only to the interests of members. They include local transport, former inhabitants and organisations. They may include reminiscences of former inhabitants. For example, the Halifax Antiquarian Society journal for 2013 had articles about Yorkshire Luddism, music at the parish church in Victorian times, the co-operative movement, the local newspaper and a locally born serial killer. Those writing the articles are often people engaged in historical research as students and teachers, or are retired people with an interest in local history.

Transactions of the Halifax Antiquarian Society, 2013. (Author)

Looking at over 100 volumes on shelves is often a daunting prospect and often an uninviting one. However, many have been indexed, often a number of a volumes at a time, and so searching for particular topics is straightforward. Some of these volumes and indexes are available online.

Allied to these volumes are those of record societies, often originating from the same time and existing in the same quantity, which aim to reproduce documents relevant to the county’s history. The Chetham Society, covering Cheshire and Lancashire, and the Surtees Society, covering Durham and Northumberland, are two examples of such which date from the mid-nineteenth century. These volumes reproduce memoirs, diaries and letters from individuals in the county’s history. Or they can be medieval accounts or trial records or the minutes of county or corporate government, churchwardens’ accounts and so forth. The Sussex Record Society has had volumes published on the printed maps of the county, 1575–1900, cellarers’ rolls of Battle Abbey, 1275–1513, Lewes Town Books, 1542–1901 (3 volumes), Sussex wills up to 1560 (4 volumes), correspondence of the Dukes of Newcastle and Richmond, 1725–50 and Acts of the Dean and Chapter of Chichester, 1545–1642. They are often indexed by name and topics, so searching for a particular subject is straightforward.

A journal which should be read by all those interested in local history is The Local Historian, which began life in 1952 as The Amateur Historian. Most local studies libraries keep complete runs of this journal. Each issue contains a small number of articles about topics dealing with particular issues of interest to local historians. The journal also includes reviews of local history books and related material.

Many journals are not primarily historical in origin or purpose, but have now become so. These were for the membership of organisations. They can vary considerably in interest to those who are not members but whose ancestors were. Parish magazines were produced by churches once they had largely literate congregations in the late nineteenth century. They were, and are, produced monthly. There will be usually an address by the vicar, often on spiritual or local issues, which can be of great interest. Just as significant is contemporary information about church societies, upcoming events and lists of church voluntary workers (churchwardens, Sunday School teachers and so on). In the past, and to a lesser extent now, churches run social and sporting groups such as youth clubs, mothers’ meetings and football clubs. Of less interest are short stories, which were a regular staple of magazines and newspapers, but even they give a flavour of the type of fiction that your ancestor may have read.

School magazines often survive, especially for grammar and public schools, sometimes published twice or thrice per annum. If your ancestor attended the school, these are of obvious interest in case they are mentioned therein or if they wrote an article, poem or story. It is usually only the minority who win prizes or are members of the sports teams or who write articles/poetry for inclusion or who hold positions of responsibility (as a club captain or as a prefect for example). However, for the minority named as well as the majority who are not, these are an excellent source for the history of the school when your ancestor attended it. They help show what the school’s values were and the events which took place there. They may detail fund-raising activity and the school’s reaction to momentous events such as the Armistice of 1918. Their limitation is that they will not dwell on or even hint at activities at the school which show it in a bad light, such as disobedience or inept teaching (other records such as school log books and punishment books may be helpful here). If the school still exists, contacting the school librarian if there is one, or else the headteacher, is probably the best method of access, but local studies libraries may well hold copies. The British Library is another source, especially for well-known schools, such as Wakefield Grammar School. Former pupils and staff may have kept some. However, in most cases, magazines only survive for a few years and many schools did not create them.

Student magazines often exist for further education colleges and universities and can certainly provide an alternative view to the more official publications. Produced by students for students they can often suggest that the students are workshy and obsessed with drink and sex, or/and are stridently extremist politically speaking. However, social and political concerns among students are often featured (e.g. safety on campus) and so provide a counterpoise, and activities run by the student union also appear. Letters by individual students often give diverse views, too.

Work-based journals are often created by large organisations with hundreds or thousands of employees. These are often the official mouthpieces of the employer, and, as with the school magazines, are unlikely to feature controversial activity or discordant views. Yet if your ancestor was employed in this organisation, they are of clear value, if one always bears in mind the bias. There will be reports on the firm’s progress towards meeting its goals in production and profit. Training courses will be mentioned. Employees who excel will be feted. Retiring employees may also feature. Social events will be reported. In the past, firms often provided sports and social clubs to an extent hard to imagine now, as well as an annual dinner/Christmas party. These often feature, along with pictures of happy employees. There may also be articles about the company’s history. Trade unions may also produce publications which should be viewed in order to see a different, though no less biased, view of the firm and its employees.

Voluntary organisations also create journals, as do social groups or residents’ associations of the twentieth century and beyond. If your ancestor was a member of this club or lived in the locality covered by the residents’ association, they should be of interest. The editor is tasked by the club committee to find enough material to fill the magazine. This will usually include a record of the committee meetings in varied detail, a letter by the editor covering an important contemporary topic; perhaps a campaign or perhaps a commentary on the club successes or otherwise. There will probably be some advertising by local firms and then articles by other members or others whose arm the editor has been able to successfully twist. Sports and other clubs will list match fixtures and results. Forthcoming social events will be listed, and later, their results (who won the quiz or darts match for example). Not all clubs produce these and not all survive, but where they do they can provide a unique insight into an aspect of your ancestor’s life or the concerns of the neighbourhood in the case of a residents’ association campaigning for a better quality of local life.

There are also books which were not published as histories, but have become so over time. Counties and towns often had guide books written about them. These were often not intended for use by visitors, unless that town was on the tourist path – historic cities as Oxford and Winchester, or seaside towns, or capital cities – but by its inhabitants. These were often published by the council or the chamber of commerce and included considerable detail about the town as it then was (as well as adverts for private schools, shops and nursing homes). This would give information about the public authority running the place, about shops and industries, schools, transport, its history, leisure activities and would usually be well illustrated, include a map and local adverts. They were often published at intervals throughout the twentieth century but more recently tend to have been superseded by websites.

A similar form of publication are directories, whose heyday was the late nineteenth and early to mid-twentieth centuries. Their origin lay in the seventeenth century and some were still published in the 1970s by firms such as Pigot’s, Kemp’s and best known of all, Kelly’s. The obvious genealogical use of these lays in searching lists of householders, shopkeepers and streets, but they do contain other information as well. Since each usually covers a town or county, there is often a great deal of general information about that place at the beginning. For county directories, which are usually divided by alphabetically by parish, each entry begins with a description of that parish and its amenities before listing tradesmen and a select list of its inhabitants. This information is similar to that given in borough or county guides, but directories were usually published annually, not at intervals of a few years as with the guides.

Neither of these two contemporary sources is designed as a candid and frank account of life in these districts. They were designed to show the attractions of a district to a potential newcomer, whether businessman or resident, as well as providing general information about those already in existence there. As with postcards, the less benign aspects of local life will not be mentioned. Newspapers may supply this defect.

CASE STUDY

From the Pigot’s Directory of Middlesex, 1832.

HORNSEY, CROUCH END AND MUSWELL HILL

Hornsey is a village and parish, in the hundred of Ossultone, about 6 miles N.W. from the Standard, in Cornhill; agreeably situated in a vale, through which passes the new river, and is surrounded by hills commanding varied and beautiful views of London and the adjacent county. This place was anciently called Haringay; it has from a remote period belonged to the see of London, and the Bishops had formerly a park here. The parish comprises of the hamlets of CROUCH-END, MUSWELL HILL and STROUD GREEN, and greater part of the village of HIGHGATE. The places of worship are, the parish church of St. Mary, and a Baptist chapel at Crouch End: the church is of considerable antiquity, and in appearance peculiarly pleasing, being nearly covered with ivy. The charities comprise a charity school upon the national plan for 50 boys, who receive clothing and another for 50 girls; also several benefactions for apprenticing boys, and for other charitable purposes. Here was situated the Hospital and Dairy farm belonging to the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, the wells of which still sustain a reputation for medical efficacy; and at Muswell Hill was anciently a chapel, dedicated to the Virgin; much resorted to by pilgrims before the reformation; the principal attraction to visitors at this period, is the extensive landscape viewed from the summit, which embraces a delightful range of prospect over the metropolis, and the counties of Essex, Kent and Surrey. This neighbourhood is perhaps one of the most agreeable districts round London, and is inhabited by persons of the first respectability. The entire parish, contained in 1831, 4,856 inhabitants.

There then follows the times of the post and the post office, listings of gentry and clergy, the academies and schools, shopkeepers and traders, taverns and public houses, coaches and carriers.

The final type of contemporary publication which was never meant to be used for historical purposes is the electoral register. As with directories, the obvious use for family historians (looking up names) is not the only potential value of such books. Since the franchise expanded in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, their value has increased as a form of recording, year by year, voters. They show a street or neighbourhood in a way that no other source after the most recently available census (currently 1911) can, as they are published annually (save for the years of the World Wars) and list all adults eligible to vote. It is possible to find, for example, when/if houses were subdivided into flats or how a district changed socially, perhaps because of immigration. In the former case, often builders foresaw that property would be resided in by the middle classes as single-household residences, but were unable to sell/let them to the envisaged market and so several working-class families lived there instead. Or perhaps the middle-class occupiers moved out and so the house was subdivided into flats for those on more modest incomes. Names of voters can indicate how the ethnic make up of a street altered over time; Polish names and Indian ones are easy to spot. However, those of West Indian residents are not always so (e.g. Beresford Brown, resident at 10 Rillington Place in the early 1950s, was a Jamaican), so care is evidently needed here. Electoral registers can also show the level of population density. Poorer districts tend to be far more densely populated than affluent ones, but children, ineligible to vote, are not recorded in these registers. However, looking at other families in the same street or neighbourhood as your family can show how an area has changed whilst your family were living there and might provide a clue to why they moved, if they did so.

British Museum. (Paul Lang)

Books are very accessible because, unlike many sources for local history, they have been published and survive in multiple copies. They are usually available on open access on the shelves of the library part of a record office (or in a bookshop), though rarer items may be locked away in cabinets. Some books can be ordered via inter-library loan. Others can be bought either second hand in bookshops or increasingly via online book shops, if they are not still in print (most have a limited shelf life in conventional bookshops unless they are best sellers).

Guides to counties or even the whole country, sometimes written by a traveller, are another form of book that can be interesting. They provide commentary about their experiences and about the places they visit. Sometimes these can be highly personal. This often makes them far more colourful, provided the reader is aware of possible bias. One famous late eighteenth-century traveller was retired soldier, Viscount Byng. Others include Celia Fiennes, writing at the end of the previous century, and Daniel Defoe’s Tour of the Whole Island, first published in the 1720s. In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries books concerning whole counties were often published, with a few pages devoted to each town or village. Arthur Mee’s The King’s England, published in the 1930s, was a series of books covering all of England’s counties, usually one per volume (three for Yorkshire). These books often concentrated on buildings of historical interest and on the journeys of the travellers, who also comment on the inadequacy of the accommodation they have to put up with. Some, such as Defoe’s and Mee’s were updated years after the deaths of their authors. The views in these books are inevitably dated, but this serves to give a flavour of the times in which they were written.

Byng’s remarks on Brighton before it had become a popular resort can be cited as an example:

Brighton appear’d in a fashionable, unhappy bustle, with such a harpy set of painted harlots as to appear to me as bad as Bond Street in the spring, at three o’clock pm.

The Castle is reckon’d a good tavern, and so we found it completely; and most comfortably too, after our walking the Steyne, entering the booksellers’ shops, sitting by the seaside and endeavouring to look like old residents: but not till we had been equipped by the masterly comb of Mr Stiles.

Nothing could be better than our dinner and the two bottles of claret and port that Wynn and I soon suck’d down: and then sighed for more wheatears after the many we had eaten dress’d to perfection. We then saw the magnificent assembly room here; and tho’ we could not stay to see the play, we had a peep inside the Playhouse … We did not leave Brighton till past seven o’clock; where is plenty of bad company, for elegant and modest people will not abide such a place!

Published diaries and letters are another great source – those for mid-eighteenth-century Sussex include those written by Thomas Turner and Sarah Hurst, and for Oxford and Norfolk in the same century, Parson Woodforde’s are worth consulting as well as being an entertaining insight into the lives of the ‘middling people’, just as Pepys’s and Evelyn’s are for seventeenth-century London.

Books are the most accessible format in which to find information about local history. Depending on the amount of time and energy you have you may be content to read a selection of what is available. They vary considerably in value, depending on the author’s skill in both research and in writing. Yet as a first port of call for the history of a locality or facets of it, they are hard to ignore, if only because they lead to other sources. Yet there are many more sources to explore as we shall see.