PHOTOGRAPHS AND ILLUSTRATIONS

A picture is famously worth a thousand words, but some are more valuable than others. Documents and the written word will hopefully conjure up a mental picture, but this has to be informed by imagination (sometimes a dangerous matter for anyone interested in history) as well. Physical pictures are even better, because imagination can be ruled out. They recreate a moment in time, otherwise lost forever.

We are all familiar with those old photographs of our family in the present and near past. The latter tend to include pictures of important family occasions, such as marriages, educational achievement, new babies and school classes. They might also include photographs taken for special events such as military service or sporting success. If we are lucky we will know who the people in the photographs are, or their names will have been written on the back, and hopefully we have an idea of when and where they were taken. Unnamed and undated photographs of people in the past are the most frustrating of all. However, fashions of the sitters, especially if female, can help give an approximate date. Yet apart from these valuable photographs, there are others.

The digitalisation of photographs has proved irresistible for some of those institutions which hold them in quantity. This is not surprising because they are attractive and interesting and lend themselves to being easily searched.

There are a number of general websites dedicated to British photographs; www.oldaerialphotos.com gives bird’s eye views. Others include www.cyndislist.com.photos and www.imagesofengland.org.uk. Collections of regional photographs can be found at www.collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk for London, www.ideal-homes.org.uk for six southeast London boroughs, www.westsussexpast.org.uk/pictures, www.picturethepast.org.uk for the northeast of England, www.leodis.net for Leeds, www.picturesheffield.com, www.chesterimagebank.org.uk and www.buryimagebank.org.uk. Photographs of London’s transport can be seen at www.ltmcollection.org/photos; Aylesbury prisoners at www.buckscc.gov.uk/leisure-and-culture/centre-for-buckinghamshire-studies/online-resources/victorian-prisoners; those of 8,000 churches can be seen at www.genuki.org.uk/big/churchdb. And there are many more, of all sizes.

It is now time to examine the history of photographs and photography to learn their significance and limitations for family history purposes. It was a process invented in France and England in the early nineteenth century and photographs began to be taken in the 1840s and 1850s. Initially they were few in number. Most were taken by professional photographers who were often chemists and set up in business in towns and cities in the nineteenth century. They would take photographs of individuals, couples and families for special occasions, and working-class as well as middle-class people were photographed (some of Jack the Ripper’s victims were photographed with their husbands before their decline into poverty and prostitution). Pictures were also taken of war scenes in the Crimea and in America in the 1850s and 1860s.

But photographers also took pictures of landscapes, both rural and urban. Few exist for the 1840s, with rather more in the 1850s. By the 1870s and 1880s they became increasingly common. These are valuable sources for family history. Photographs were taken for many reasons. Newspapers, especially in the twentieth century, often commissioned photographs. They might include pictures of important events such as the reading of the town’s charter, a jubilee or coronation celebration, severe weather or events on the Home Front during the World Wars. Other organisations would do likewise.

Photographers began to set up business in large towns and cities and travelling photographers visited villages. Between 1842 and 1912 there were 633 in Birmingham. Some travelled throughout the country, such as Francis Frith, and built up extensive collections, but others did not stray far from their home town or county and so most of the early photographs of a particular place are the products of a handful of photographers.

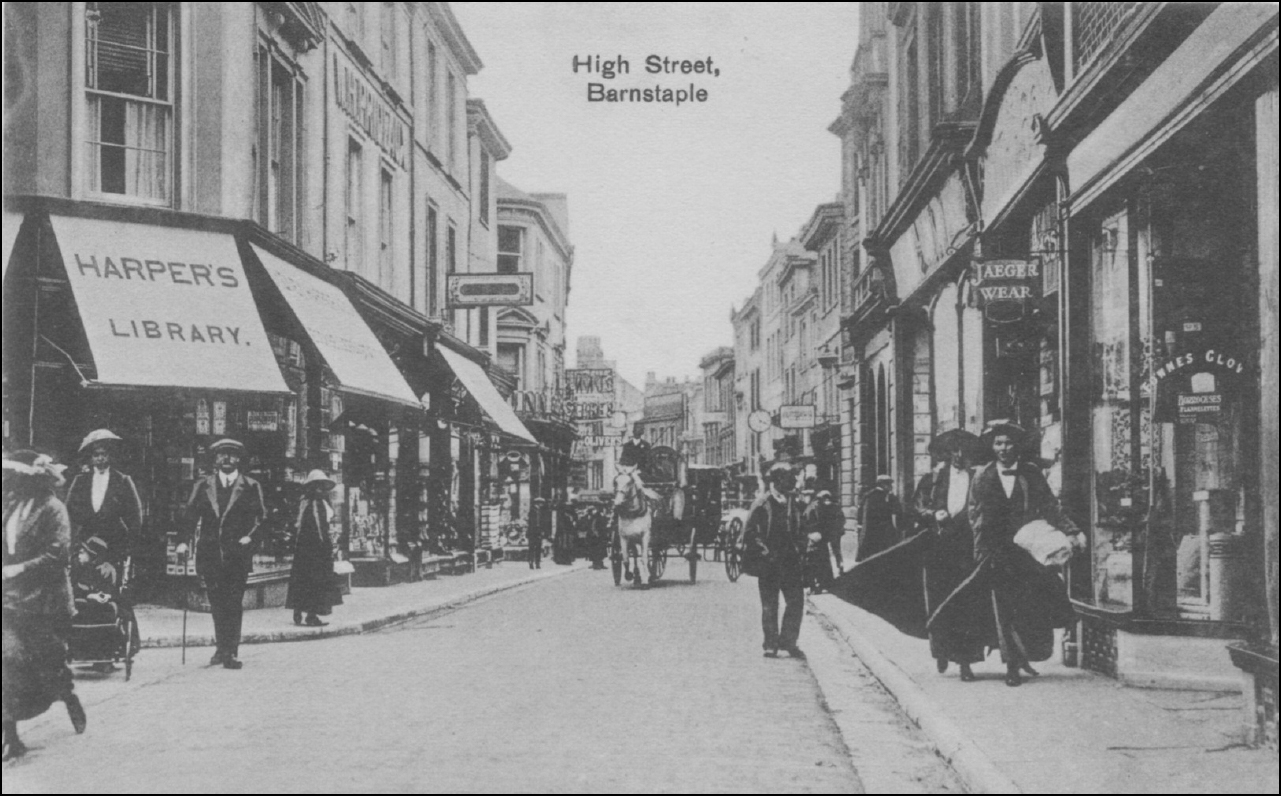

A range of photographs of the same place over decades is a photographic history of the place. It will show buildings long gone, those hugely altered and those which remain. There will be buildings which were new at the time of the earlier pictures and which were subsequently demolished. Changes in transport, from horse-drawn to combustion engine and from steam trains to diesel, and from electric trams to trolley buses to motor buses, will be evident. Changes in fashion are also noticeable. Crowd scenes are also informative and were often taken in the hope that those pictured would buy them or that the scene was of a sufficiently important event that people would buy them as souvenirs. These might include fairs, coronation or jubilee celebrations, market days, recruitment drives and so on. Adverts are often shown on photographs, mostly words, unlike today. Litter rarely appears on these scenes and streets often seem less congested.

Family photograph at Calvados, Ealing. (Paul Lang)

Technology changed throughout the history of photography. The first photographs were daguerreotypes, which required considerable immobility on the part of the subject matter. William Fox Talbot invented the paper negative in 1838–41 and this allowed shorter exposures. The wet plate of the 1850s did even more to usher in an army of photographers who could be mobile, with a dark room in their wagon of equipment. By the 1880s there were hand-held cameras and dry plates, so photography was now also in the realm of the wealthy amateur photographer.

Sometimes photographic surveys were taken of particular districts at a given year in time. The Croydon Natural History Society made a photographic record of Surrey in the first half of the twentieth century. There was a photographic survey of Horsham in the 1950s. There were also surveys of Caterham and Lambeth in the 1960s. All these soon acquired historical significance.

Hoddesdon High Street, Hertfordshire, 1981. (Mrs Bignell)

The difficulty with photographs is that they may be undated. They may show unusual or quaint people or places, rather than commonplace ones, and may well be untypical of the time and place and therefore less useful as a reliable historical source. Locations of photographs maybe unknown if there is nothing recognisable or identifiable using other sources. Pictures of side streets and fields often fall into this category. Photographs can be wrongly labelled in both books of old photographs and even within local studies collections; archivists and local history librarians cannot be expected to know every building past and present within their jurisdiction.

Clues to dating and locating the whereabouts of particular pictures exist therein. Transport shown in a picture can help to date it, and, if the picture shows a tram or bus, then this will narrow down the location because they will run only on specific routes, usually the principal roads of a town or city. Costumes worn by people in the picture, especially if female, can also help date the picture, as the era of the fashions can be ascertained. If there are shops in the picture, reference to relevant street directories can both locate and help date the picture. If a postcard, the stamp and date mark on the reverse should also narrow down the date of the picture, but bear in mind that a postcard with a date stamp of 1906 may well have been taken up to several years earlier. However, if the scene is purely residential or shows a nondescript garden or open space, identifying the picture is far more difficult and may be an impossibility

Initially photographs were only taken by professional photographers and wealthy amateurs. Equipment was expensive and developing pictures was time consuming. It was not until the early to mid-twentieth century that photography became a mass pursuit.

One excellent source of photographs from the past are postcards, about three inches by five in size and usually landscape. Initially these dated from about 1870 in England, following their invention in Austria in the previous year, but were blank on both sides (one for the address and one for the message) and were a cheap and reliable form of communication useful in a society when universal education had led to increased literacy. However, by the 1890s illustrations began to appear on them, but only on half of one side (the other half was blank for the message) and so pictures and messages were restricted.

Barnstaple High Street. (Paul Lang)

In 1902, the Post Office allowed the picture to appear on all of one side of the card, making the postcard a mini work of art. Photographers, apart from taking studio photographs, began to photograph local scenes, such as prominent buildings (churches, town halls, historic places, schools) and attractive places such as bridges, rivers, woods, parks and commons. But they also took pictures of residential streets as well as shopping streets (these often appeared in limited runs and were sold from door to door). These featured people and transport as well. Sometimes disasters were depicted: fires of buildings or air raids in the First World War. Their heyday was about 1900–20. Some were black and white, some were sepia and some were hand coloured. Their main drawback is that they are very selective and some views are very rare indeed; small side streets, slums and factories will generally not appear. This is because these pictures were not meant as historical records but as attractive pictures.

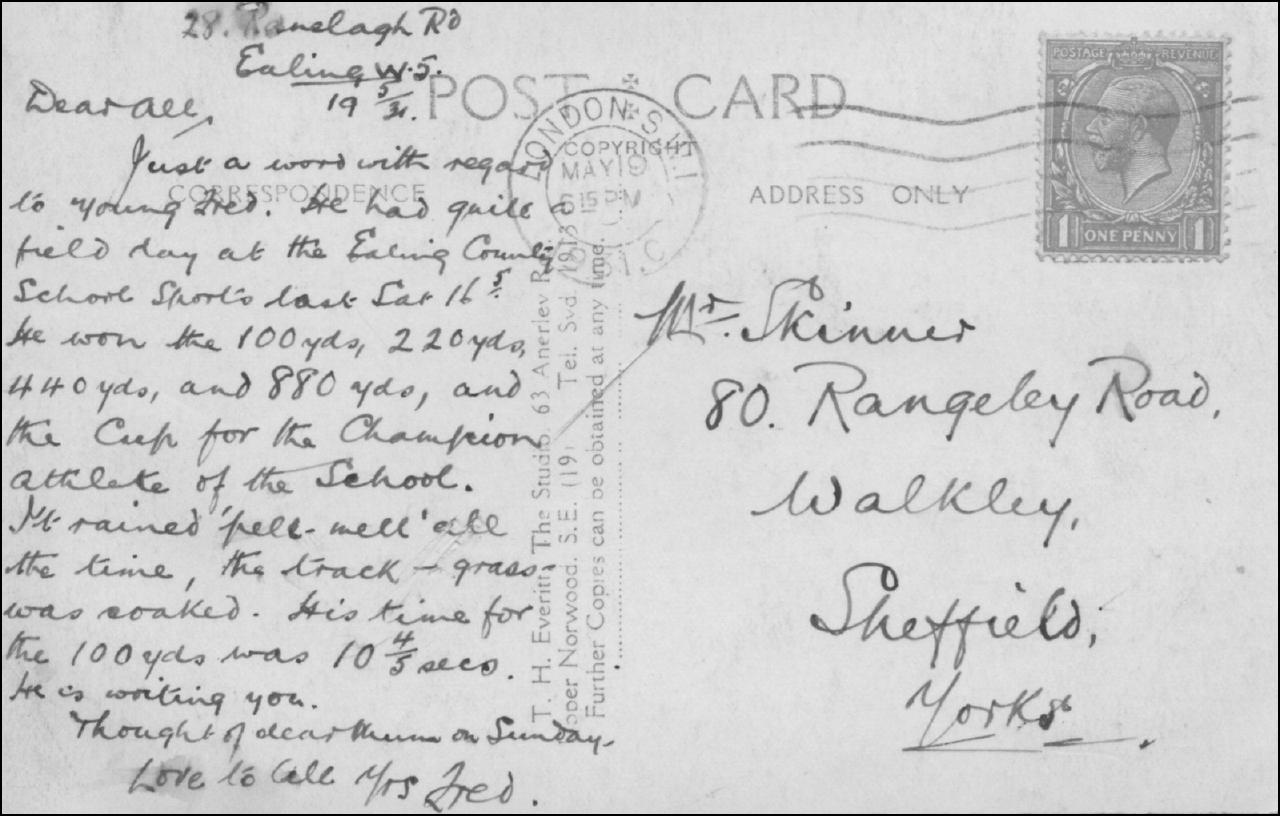

People would use postcards as a popular form of communication, as messages on their reverse attest; they were used to arrange meetings as well as to pass on news. The postal service was far more frequent in the early twentieth century, with numerous deliveries per day, compared to only one in the early twenty-first century. Postage was cheap; a half penny only before 1914. The industry boomed and companies from overseas also began making postcards of places in Britain; before 1914 there were several German photographers who did so.

As the twentieth century progressed, postcards became less popular due to higher postage charges, the increased number of cheap cameras and greater usage of the telephone. They became reduced to being of tourist attractions and postcards of ‘ordinary’ views became almost extinct by the middle of the century. It should also be noted that some postcards include the messages written by the sender and these often provide a fascinating insight into that writer’s life and concerns.

Reverse message on postcard. (Paul Lang)

Postcards can be accessed in a number of ways. First, museums, libraries and record offices often sell reproductions of old postcards and these can be bought cheaply. Secondly, books showing reproductions of old postcards are fairly common. Thirdly, genuine old postcards can be bought, at varying prices, depending on both rarity and content (e.g. pictures of fire engines and fire stations are often rather expensive). They can be bought at postcard collectors’ fairs as well as postcard shops. Or it is probably easier to look on eBay and type in the name of the place one is seeking and add ‘postcard’, to bring up thumbnail sketches of those which meet the category sought, together with price and details of seller. Some can be seen online, perhaps on a local history society’s website.

Organisations often have photographs taken for the purpose of forwarding their own business aims. The acquisition or hoped-for acquisition of new land, property or equipment might be an occasion for photographs to be taken. Special events such as a presentation or an annual social event or party might be recorded for posterity, as might a retiring member of staff. The launch of a new project or its culmination might be another occasion for photography.

Newspapers in particular have been using photographs since the early twentieth century. Those which actually appear and are now viewed digitally, on microfilm or occasionally on paper, are usually of low quality. However, the originals, or good copies, sometimes survive, and are often are available in record offices. These will usually only be a sample of all the photographs ever taken by the said newspaper. They will usually be of people and of events, rather than places. Councils may have photographs of councillors and public buildings; churches may have pictures of major events in the life of the church’s clergy, people and buildings.

Individuals also take photographs, and increasingly did so as the twentieth century progressed, when cameras became cheaper and easier to use. By the 1950s they were in reach of most people. Many pictures taken are of family and friends, especially on significant occasions and on holidays; some may be of other events and places. Most rarely reach a record office or library for public consultation and when/if offered would be heavily weeded.

The use of photographs is that they give a snapshot into the past, into buildings and localities which may no longer exist or if they do will probably be substantially different. Most collections will be mainly topographical, showing streets, shops, buildings, especially prominent or picturesque ones, landscapes and parks, from different time periods. Some may be of these places during or after unusual events, such as after a flood, or during a fire, or perhaps a man-made disaster, as with the aftermath of bombing in the Second World War. Large and prominent places will be more photographed than others; expect more pictures of a major shopping street and of a railway station and less, if any, of small residential streets. These photographs may well include people or transport appearing incidentally on them.

Collections of pictures can often be seen in local studies libraries. These include those of newsworthy people; visiting celebrities, local and national politicians, centenarians and others. These may be of less interest, unless your ancestor is among these. Perhaps of more interest are group photographs; of schoolchildren, local police, fire or ambulance personnel, or of sports teams. Not only is there a greater chance of an ancestor being present, but they give a little clue to people who your ancestor may have known or have seen. Events may have been photographed: a protest march or strike, or a carnival or other social, political or religious function. These will add colour and a further dimension to what is known about such events which your ancestor may have been witnessed or have been involved in. There might also be photographs of objects, from recycling bins, street lamps or even prototype tanks made by a local inventor.

Local studies libraries usually have thousands of photographs in their collections, dating from the later nineteenth century onwards. As with all such collections, they will vary in quantity considerably, depending on how successful they have been in collecting what has been taken. Certain subjects and time periods may predominate. They might have received a large deposit of photographs taken in the 1950s and 1960s by a local photographic society or from a newspaper in the 1970s. Conversely there may well be few photographs taken during the First World War or the mid-Victorian era.

There are also important national collections of photographs, too. The National Archives has a large collection of over 13,000 from 1920 onwards. The Guildhall Library in London has over 10,000 pictures of London from the 1850s onwards; mostly central London and the City, but also of what were outlying districts in Middlesex, too.

The largest single collection, however, is the English Heritage Archive at Swindon, once known as the National Monuments Record for England, focusing on architecture from 1859, with about 12 million items in the collection. There is also a substantial collection of aerial photographs, too, as well as drawings and plans of buildings and man-made structures, from country houses to coal mines. By 2015, over half a million of these can be viewed as thumb nail sketches online and over a million can be searched for by keyword online, too. Copies can be ordered electronically.

Given recent advances in technology and new funding streams, digitising picture collections has proved a popular option for many record offices and local studies collections (those held by Manchester Central Library and Leeds Local and Family Studies Library have been made available, for example). Some collections will be available on the organisation’s website, though it is rare for all the collection to be there. Most of these online collections can be searched by keyword, so it should be fairly straightforward to locate what you wish to find without even visiting the place. Copies can usually be made, though a fee will be payable (if it is not for publication elsewhere, this should be moderate). If collections are not digitised, it is usually possible to take copies on site, depending on copyright issues (currently a photograph, as with any work of art, remains the copyright of the creator or their heirs until 75 years after the creator’s death). Again, a fee may be payable.

Many photographs are in private hands. Postcard and photograph collectors have their own collections and whilst many are duplicates held elsewhere, some may well be unique. Postcard societies and collectors’ clubs exist where the likeminded can meet and discuss their collections. They have talks or create books of their collections. One society is the West London Postcard Club, www.chiswickw4.com/community/wlpc.

As with all evidence, care must be taken when judging how representative photographs are of contemporary life. To help with this, the key question to ask is why the photograph has been taken and to consider the occasion. In some instances we can never know this, but in others we can usually make an educated guess. The camera may never lie, but the pictures it takes may be designed to give the viewer a certain impression that those responsible for the picture wish to give. For instance a picture taken of slum dwellers appearing downcast and miserable may have been taken by a social reformer or one who advocates that measures be taken to improve the housing stock of that particular district. Dr Barnardo was accused of making impoverished orphans look even more wretched in order that they could be photographed in that state, together with a later photograph showing them to be smart, a tribute to the work in his homes, to be used as propaganda, encouraging donations. To show the same people having fun, e.g. children playing football or skipping, would not have the same impact. Likewise, a business will want to show contented employees working in hygienic conditions, especially if food is involved. This is not to say that these pictures have been faked or are unreal, but they may not be wholly representative of conditions which they are portraying.

Postcards and photographs can also be incorrectly labelled by either the photographer, who may not know the district well or may choose to label it incorrectly. Pictures in libraries and record offices may have been wrongly titled. There is also the temptation for a photographer to take pictures of extraordinary events or particularly picturesque scenes or costumes, e.g. villagers taking part in a medieval themed play in the 1920s rather than their being photographed in their ordinary clothes on their way to work.

Often photographs of what we want to see simply do not exist. Wartime censorship resulted in relatively few private photographs being taken then. Those that were were often commissioned by civil and military authorities, and if for public consumption, will tend to shy away from the more unpleasant aspects of conflicts. However, they often show bomb-damaged buildings and streets, civil defence workers, military activity and parades, street parties at the war’s end and these are of obvious interest.

Paintings and Prints

Apart from photographs there are two other major sources of images held. Both cover the pre-photographic age. The first are prints, which, compared to photographs, are relatively few in number, but are often the only visual representation of places and people prior to the midnineteenth century. They tend to focus on significant people and places; churches and large houses rather than cottages, workshops or workhouses. Yet humbler dwelling places featuring in general views of villages and towns can be the only visual representation of these places centuries ago. They will certainly be few in number, but are clearly better than nothing. Local repositories have collections, as do museums and art galleries. The National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery have substantial collections, which can be searched online. Prints are usually black and white or greyscale, but a few are coloured. Some appear in published works – older histories and The Gentleman’s Magazine, for example.

Painting of St Augustine’s church, Broxbourne, 1999. (Author)

The other visual source are paintings. Again, these are few in number because a great deal of time, talent and effort is needed to create such a work of art, whereas numerous photographs can be taken in the same time. Individuals and members of art groups often choose local views, though certain ones are very popular (e.g. a picturesque church is a more likely subject than a row of terraced houses). Paintings, of course, can be very variable in quality depending on the artist’s skill and can potentially be rather subjective. Yet they are unique creations and are in colour, unlike photographs from the nineteenth and early to midtwentieth centuries, and that gives them an additional dimension compared with other visual representations of the past. Again, the National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery have substantial collections. Paintings of local scenes are still being painted, often with varying degrees of expertise, but the views will almost certainly be contemporary and not (to us, at any rate), historical.

A recent project by the Public Catalogue Foundation is to scan and show oil paintings held by public institutions online. ‘Public institutions’ includes universities, libraries, record offices and museums. They can be seen on www.thepcf.org.uk and can be searched by keyword. Basic additional details (name of painting, artist, dates, size and location) are given and copies can be ordered. However, it is worth noting that most paintings are not oils and so this collection shows a small but significant number of paintings throughout the country, and it also enables increased access. Most are landscapes but some are of people and some of scenes overseas.

Generally speaking, pictures were created in abundance from the later nineteenth century and beyond. Apart from very significant people, places and events, pictures of other views and people are very rare for the periods prior to the late nineteenth century. For the twentieth century, the coverage is far better. It is very likely that you will be able to find pictures of the locations that your ancestors would have known and so provide an insight into their environments.