MAPS AND PLANS

Maps are not an obvious source for family history. They concern places and not people (geography is about maps and history is about chaps as the old saying goes). They exist in great number, especially for the last two centuries. For local historians, maps are an essential research tool, especially when they exist in a series over a lengthy period of time, in order to trace the development of a district.

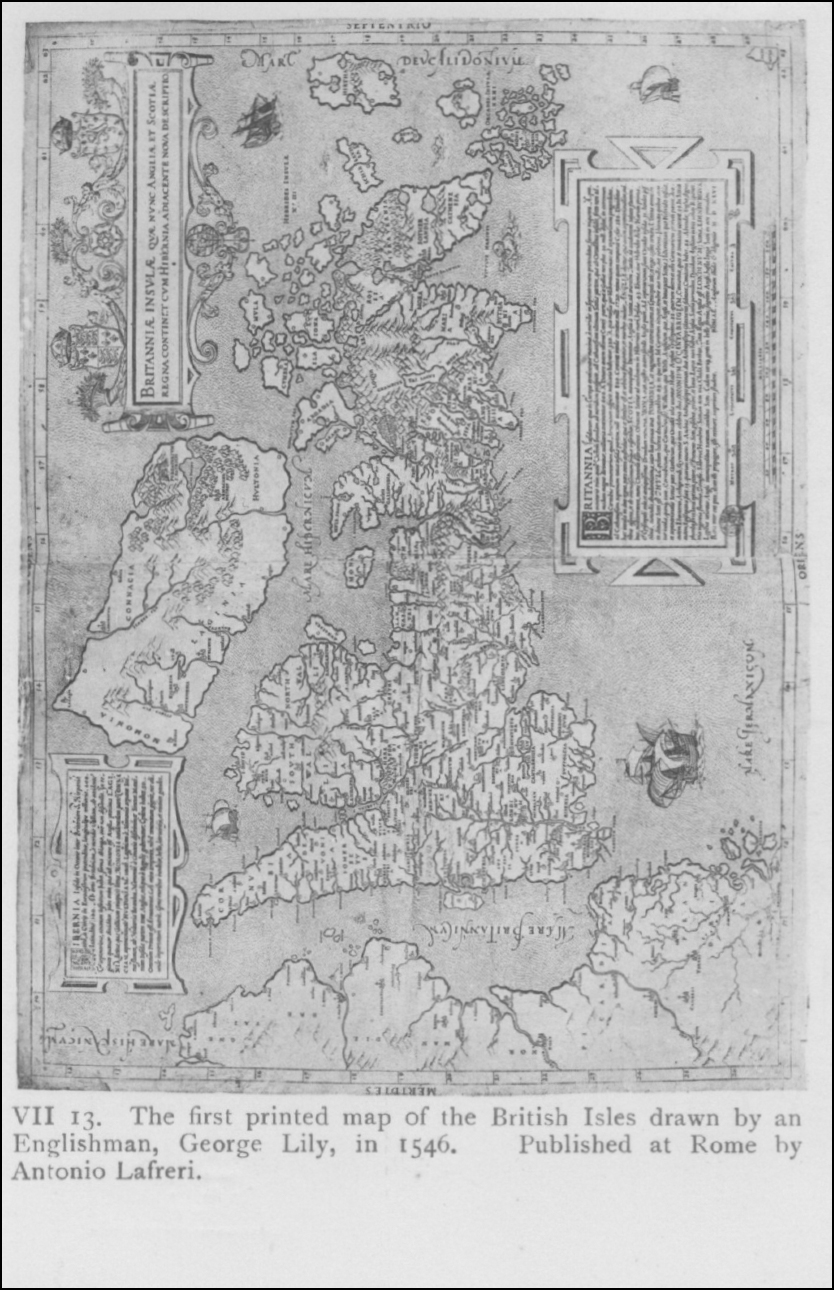

Medieval maps are very few indeed; the Mappa Mundi located at Hereford springs to mind. Nor are they very reliable. The first local map is of Inclesmoor, Yorkshire, made in the first decade of the fifteenth century. There were also some maps of towns, such as Bristol, made in this century. Very few maps were needed and in any case, the cartographic skill was lacking.

There are several websites devoted to maps: www.cyndislist.com/maps, www.mapseeker.co.uk/genealogy and www.visionofbritain.org.uk. A number for London can be found at www.collage.cityoflondon.gov.uk.

County Maps

County maps began to be made in the sixteenth century as part of the interest in topography and local history. Christopher Saxton (c.1542–1611) had maps of 34 counties created between 1574 and 1579 and these were engraved and printed by his master. They were published in An Atlas of England and Wales in 1579. These maps showed villages in their relation to one another for the first time. However, they did not depict roads between the marked settlements and were not to the same scale.

Shortly afterwards, John Norden (1548–1626) produced county maps, but this time they showed roads and distances and used a grid reference system, so the locating of particular towns and villages was made less difficult. They were produced in the early seventeenth century. He never completed his work; there were no maps of the Midlands and the northern counties. Only the maps of Middlesex and Hertfordshire were produced during his lifetime. Posthumous maps were of Cornwall, Essex, Hampshire, Surrey and Sussex. Details are sometimes suspect, though. Norden’s and Saxton’s maps were used as the basis of the maps in William Camden’s Britannia of 1607.

First printed map of British Isles, 1546. (Paul Lang)

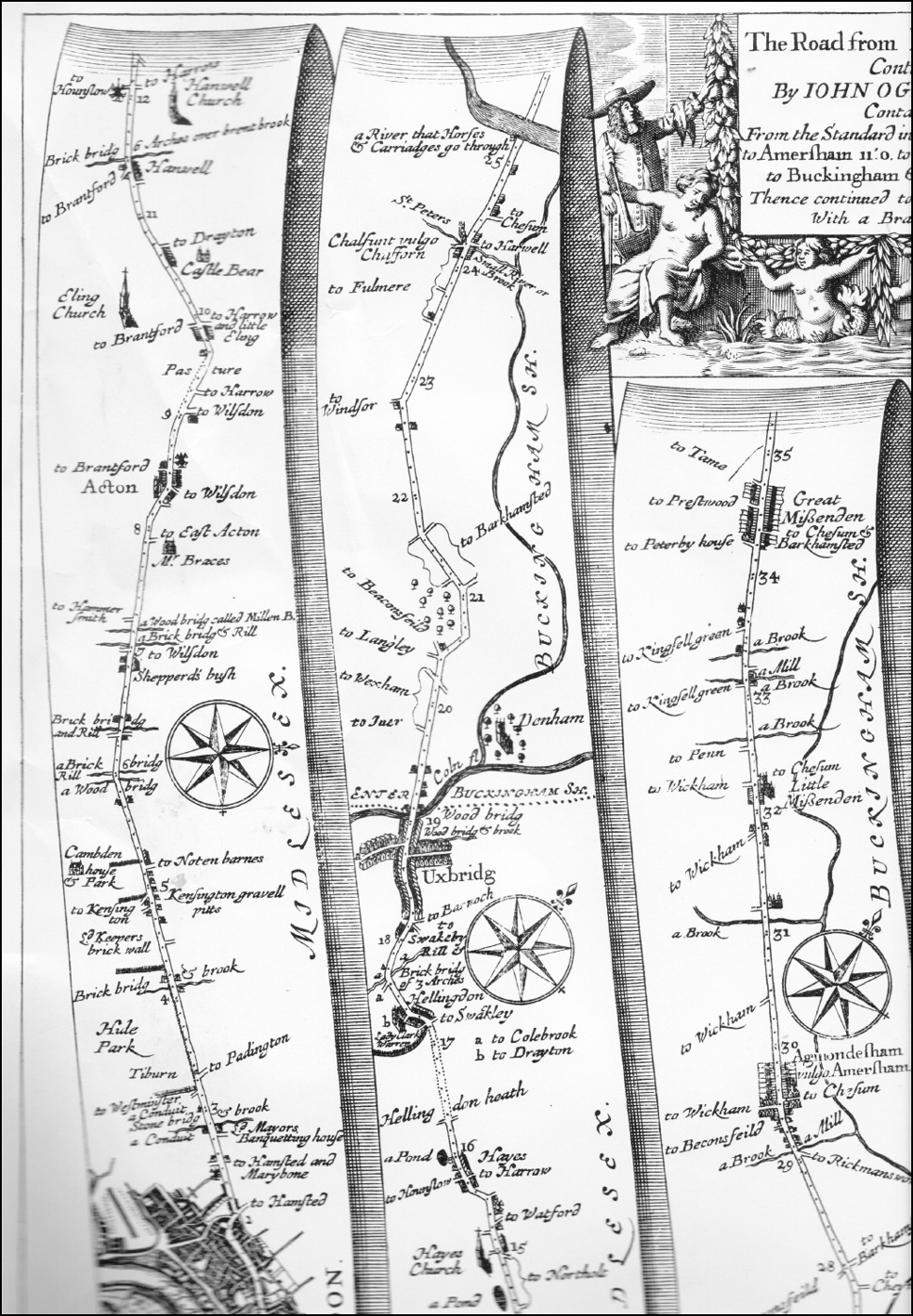

Extract from a John Ogilby map of 1675. (London Borough of Ealing)

John Ogilby’s maps of major roads and settlements thereupon were produced a century later in a book of 100 plates and titled Britannia in 1675. They are on the scale of one inch to the mile. These were aimed at travellers and had counties reduced into strips showing principal coach routes and the settlements they passed through. Roads leading off the main routes were shown, together with the settlements they led to. He noted bridges which crossed rivers and what they were built of. An updated set of these maps was produced in the following century by Emmanuel Bowen, in his Britannia Depicta or Ogilby Improv’d. However, it is not always certain that Ogilby strayed from the main roads; for example, he depicts St Mary’s church in Hanwell being to the west of the river Brent, which it is not, but from the road it would appear to be so because the bend of the river is not visible from there.

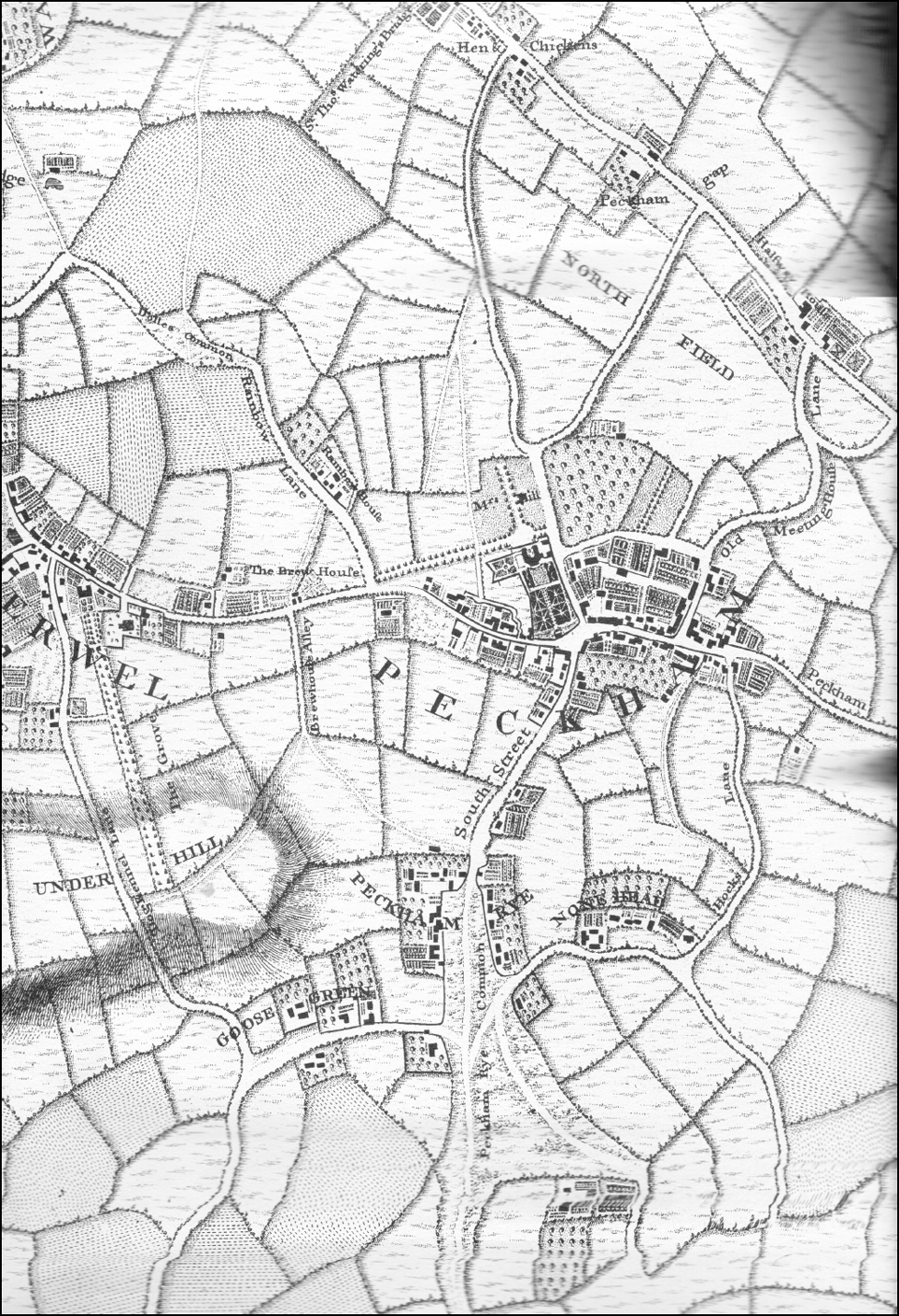

There were other eighteenth-century mapmakers in Britain. John Cary and Hermann Moll produced atlases of county maps. Cary paid particular attention to the accurate depiction of transport networks. John Rocque produced both town and county maps at this time, and is best known for his map of the districts ten miles around London as well as the city itself. It was reprinted several times. He also designed maps of Bristol, Exeter and Shrewsbury, all in the same decade. Rocque’s maps have been criticised on account of errors of distance and direction compared to later and more accurate maps, but the tools at his disposal were rudimentary. Henry Beighton produced one of the best county maps of the century, but of only one county, Warwickshire, one of the first to be based on trigonometrical principles and was one inch to the mile in scale. County maps were still being produced in the nineteenth century.

Town and Village Maps

City and town (not village) maps began to be made in the sixteenth century. The very first was of Norwich, then one of the most important cities in the kingdom, by Dr William Cunningham in 1559. However, their quantity greatly expanded in the seventeenth century. John Speed was the first major mapmaker of such, including maps of a number of the county’s principal towns as part of his series of county maps at the beginning of the seventeenth century. These were based on the earlier maps by Saxton and Norden. They were often highly illustrated and attractive pieces of art. They often adorned the walls of the houses of the well to do, especially if their properties or names were depicted there. The maps were black and white, with the intention that they could be coloured by seller or buyer. Most of these towns had been surveyed by Speed himself. They can be viewed on www.lib.cam.ac.uk/deptserv/maps/speed.html. However, his maps were reproduced up to the next century and a half without any modifications, despite the changes that occurred in these towns in those decades.

Extract from John Rocque map of environs of London, 1741–1745. (London Borough of Ealing)

Villages mostly remained unmapped. There was no demand to justify the expense of their production. However, in some villages, where there were a number of seats of the gentry and nobility, there might be a sufficient demand to lead to such, or there might have been a need by the parish for such a map, perhaps for rating purposes. Some were created and survive, but they are generally few in number.

Enclosure maps were made of agricultural land enclosed in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and are often the first detailed maps of the parish. Enclosure commissioners had to have surveys undertaken to ascertain ownership of existing land and of rights over common land. Not all parishes were surveyed, however, and for some large parishes, mapping took years to complete. These maps are usually held at the county record office, and they should be accompanied by a schedule of landowners. These maps show the strip field system as well as land already enclosed and a second map showing the new arrangement of land in the said parish, though the former map, being of less practical and immediate use, may not always survive (more do so after 1830). Not all parishes had land enclosed (there are virtually none for Kent or Devon and only half of Northamptonshire was affected) and not all maps survive, but where they do they should not be overlooked. It has been estimated that 5,000 parishes had land enclosed. The associated paperwork is equally important. The Enclosure Award was drawn up to record the Commissioner’s decisions about various matters, such as tenure, economics and topography.

A systematic survey of much of Britain was taken in the early nineteenth century (1836–51). This was the result of the Tithe Commutation Act of 1836 where tithes (taxes paid to the church on land) were converted to rents. This led to the tithes commissioners appointing surveyors to make large-scale maps showing, parish by parish, land and property within the said parish. They also made apportionments to accompany the maps and these list, per numbered plot, landowner, landholder, acreage, land usage (house, arable, pasture, commons and so forth) and payment to be made. Buildings are also shown and are sometimes coloured to denote different types. Field names are also given. These were the first reliable maps made of many parts of the country and the first detailed, national, survey. Yet, as with enclosure maps, they do not cover every parish in the country. Only about a quarter of Northamptonshire is covered, for example. But by and large they exist to a far greater degree than the enclosure maps. They can be located at the National Archives as well as at county record offices. Their scale is very variable and their accuracy is variable, too. Only about one-sixth of these maps are deemed first class for their accuracy, some are not even based on a survey but on earlier maps.

Ordnance Survey Maps

Perhaps the most important – and accurate – series of maps was initiated for military purposes. This was the Ordnance Survey. The creation of maps for military purposes began shortly after the defeat of the Jacobites at Culloden in 1746 and was restricted to Scotland. Another war led to the Board of Ordnance, a key department of state (in 1791), initiating the surveying of the south coast of Kent in case of invasion from France half a century later. These were to the scale of one inch to the mile and were published from 1801, the first being for Kent, and are known as the First Edition or Old Series, and in 1805–73, 110 sheets (mostly 36 by 24 inches in size) were published. The next maps were of the southern counties and by 1840 all the counties in England and Wales had been mapped south of Lancashire and northern Yorkshire. Clearly these were incapable of showing detailed maps of villages and towns, but are useful for showing geographical features, communications, the locations of settlements and their growth over time.

There were further editions of the one inch scale maps as time moved forward. Maps of northern England were produced between 1840 and 1872 and then maps for the whole country were revised from 1873 to 1898. Some of the second edition were coloured. Then there was a third edition to the same scale in the decade before 1914, producing 360 sheets of 12 by 18 inches in size. The fourth edition was published between 1918 and 1926 and there were further editions in later decades, though the fifth edition of the 1930s only included southern England as that series was discontinued. These maps were continually being amended to show any changes in local topography.

Extract from 1894 OS Map of Botwell, Middlesex (London Borough of Ealing)

Larger scale OS maps were produced in the second half of the nineteenth century and these are of the greatest of value to family and local historians because they show a great deal of detail. They were produced at the scale of 6 and 25 inches to the mile from 1840 to 1900 and cover the whole country in 15,000 and 51,000 maps respectively by scale. The initial surveys undertaken between 1840 and 1854 were of Lancashire and Yorkshire and these were of the 6 inch scale. The first county to be mapped on the larger scale was Durham, which began in 1856. The rest of the country was so mapped in the next decade. There were further revisions made roughly every two decades (1890s, 1910s, 1930s). They showed streets, individual buildings (not numbered), with prominent buildings labelled, prominent features and street furniture. Ancient remains were often included on these maps. Natural features, streams, marshes, fields and hedges are depicted, as are quarries, gravel pits and pasture. Never before had such details been recorded. They also show boundaries of parishes and other jurisdictions which may not be evident by other means and may be long gone. The first edition sheets only show part of a single parish per map and leave the remainder of the sheet blank; so the adjoining sheet will be needed to show the adjoining parish (later editions showed portions of multiple parishes where applicable). Each map has a serial number, with the first two editions using the same grid and the third and fourth ones using another.

At the other end of the scale, for 400 towns and cities, there was, in the mid to late nineteenth centuries, a series of 1:500 scale maps, which is the most detailed to have been produced and shows minute details, down to each lamp post, fountains, pillar box, even garden paths. Rooms in large public buildings (such as workhouses) are often shown and labelled, and the number of seats in churches is noted on these maps. Nothing like it has been produced before or since. Most towns were only mapped once in this way, however.

After the Second World War there were new series, on a larger scale, of 1:1250 or 50 inches to the mile; these cannot be directly compared to their predecessors but, of course, show more detail. These also included house numbers, so making the task of identifying individual properties easy. They also show the elevations of selected points on each map above sea level. Those maps produced in the 1950s often show buildings which had been damaged by bombing in the war and had yet to be rebuilt (usually marked ‘Ruin’). There was another revision in the 1970s and another in the 1990s. Few Ordnance Survey maps have been published in recent years, for they are now available digitally from the OS website www.ordsvy.gov.uk.

The great value of the OS maps are that they can be relied upon for accuracy, unlike the earlier plans. Their only slight failing is that, because of their detail, they are very sizeable and so several maps are needed to be able to view a town or a geographically scattered village. It is fairly easy to compare parts of the town for different years, but not its entirety, making a comprehensive comparison difficult.

The Ordnance Survey has also produced a number of historic maps of the country in the centuries up to the seventeenth, though concentrating on the centuries prior to the Norman Conquest. Since few people can confidently trace their ancestors prior to 1066, most of these will not be of direct value. However, there is one of Britain in the late seventeenth century, with a scale of an inch to 15 miles. Monastic Britain shows medieval Britain at a scale of an inch to 10 miles and provides ecclesiastical information.

Many Ordnance Survey maps (over 2,000 at time of writing) have been reproduced by the Alan Godfrey map company of Gateshead www.alangodfreymaps.co.uk. This is not comprehensive and focuses on the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. They also come with a survey of the particular district, often by a local historian, which adds extra value. It often includes extracts from a local directory, too, and is published in a short and easily portable format (which is not the case with full-scale copies or originals of OS maps), so tracing the places on the ground is relatively straightforward.

Care needs to be taken with maps as with any other historical source. First, there is a time lag, often of some years, between the time that the survey was made and the time that it was published. For instance a map of west London dated 1874 does not show streets which we know from rate books existed in 1869. Secondly some maps may not be wholly comprehensive in their depiction of geographical features. So we must take care and check with other available sources.

Other Maps

There are also other maps which were produced. The Charles Booth Poverty Map of what is now inner London is well known, though perhaps not as much as it should be amongst family historians. It shows London streets, graded by wealth. Gold represents the wealthiest, with various gradings of red and blue shades to denote the middle and working classes. Lowest of all were those marked in black, showing streets inhabited by the semi-criminal and vicious. Do remember that these gradings were of a moment in time (1886–1903), and over the years streets may well have altered, being either gentrified or falling into the slum category. They can be viewed online at www.booth.lse.ac.uk.

Other one-off maps include those showing bomb damage in the Second World War. Local authorities commissioned such maps, often using 6 inch OS maps and then annotating them accordingly. These might show the dates when bombs fell and the type of bomb (oil bomb, high explosive, V1, V2 and others). Not all bodies created these and nor, if they did, do they all survive. But where they do they give a graphic portrayal of which parts of a town or city were worst hit, and when. Earlier military maps showing towns and their role in conflict were made following other warfare, including Preston after the battle there in 1715 and Carlisle after its sieges of 1745.

Archaeological surveys are often made when new buildings are erected. These result in a collection of maps for that particular site being drawn together, with details of any archaeological finds on the site and with other contextual information, all in one place.

In the first half of the twentieth century and beyond, slum clearance was a major policy for councils, replacing them with council houses or, after 1945, flats. These resulted in maps and plans of the new estates being drawn up. Local authorities and companies often had to commission plans when undertaking the building of new roads, new buildings and new housing estates. These resulted in detailed plans; for buildings these often included elevations as well as plans, often in great detail, showing windows, doors and other features. Plans of individual buildings and extensions to them sometimes exist, too. Drainage plans were an absolute imperative from the nineteenth century onwards, and all councils, often in their town planning departments rather than their archives, should hold them, perhaps microfilmed or scanned, for use. Plans of schemes never undertaken may also be held, giving an insight into an alternative future that was never to be. For example, in Ealing there is a depiction of a middle-class housing estate, with detached houses and neatly laid out streets and gardens, which was only partially realised.

Other new utilities also meant the creation of maps. These include canals, railways and improvements to docks. After 1794 these plans had to be deposited at what is now the Parliamentary Archives because they were needed to accompany the Private Act of Parliament which had authorised them. Local copies may be held at the appropriate county or borough record office.

Maps can pinpoint where an ancestor was baptised, married or buried, where their wife/husband’s family lived, where they went to school, where they worked or where they enlisted in the armed forces or where they spent their leisure hours. You can trace how they probably travelled to these places which were important in their lives.

We should not neglect geological maps for geology played a crucial part in a district’s history and the employment of many of its inhabitants. There have been a number of geological surveys, or rather revisions from the 1860s. Some are one inch to the mile; others are 6 inches to the mile, superimposed on OS maps. These maps are coloured in order to show the different types of soil, such as gravel, chalk, London clay, brickearth, alluvium and flood plain gravel. There are also comments on the maps, such as ‘gravel formerly extensively dug over this area’. Comments about archaeological finds and the depth of earth are also sometimes noted.

Estate maps are another source. They can vary in scope a great deal. If the village where your ancestors lived was part of a large estate, as many were, then the land may well have been surveyed as part of the owner’s attempt to learn exactly what he owned and how best to make use of it. They were also created when a sale was impending or to solve land disputes between neighbours. Or the plans may show individual farms and their lands. Only about a tenth cover an entire parish; some straddle several. They can date from as early as the sixteenth century up to the nineteenth, so are especially useful for they may be the oldest detailed map of part of a village or town. Field names are often given, as are footpaths, roads, common land, woods, but not necessarily what the land was used for. For the pre-enclosure era, patterns of strip farming should be shown here. Buildings, both domestic, ecclesiastical and industrial, also feature. Seventeenth- and eighteenth-century estate maps also showed industrial areas, such as the coal mines in Northumberland or the iron foundries in the Midlands. Livery companies and other institutions commissioned building projects in towns and so had maps of their intended developments commissioned. Land belonging to Oxford and Cambridge colleges was also mapped, with these surviving in the appropriate college libraries. Most, though, are held in county record offices, some at the National Archives and the British Library, and number in their tens of thousands in total. Their existence and survival is patchy, as it is with all pre-OS maps. For Kent, a little over a quarter of its parishes are covered (before the eighteenth century) by estate maps, for example.

Very few medieval estate maps exist, for surveying was then a written not a graphic exercise. In the later sixteenth century, surveying methods had improved considerably, so estate maps began to be made in quantity. The redistribution of land during the reformation and Commonwealth resulted in land surveys being made. The greatest age for estate maps was the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, as standards were high. However, with the coming of the OS, maps began to be based on these accurate maps and the golden age of the estate map was over.

Another major collection of plans is that held at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, of the Royal Institute of British Architects’ drawings. These are mostly of prominent buildings, large country or town houses, public buildings and churches, though there are some of smaller premises, too. There are indexes.

Borough Guides, published throughout the twentieth centuries, often included a map of the locality in question. They will be of towns or suburbs but not villages. These usually include named streets, parks and prominent buildings such as churches and schools. They do not show individual buildings and detail is usually lacking. Yet for an overall view of a town, they are useful because they show it at a single glance, whereas usually several OS maps are needed to view any but the smallest of settlements. Maps also often featured in directories from the eighteenth to the twentieth centuries.

Maps and plans also feature in deeds to property, which, in the later nineteenth and twentieth centuries, tend to include a block plan of the property sold or rented. These will show the extent of the garden/yard, location of other adjoining properties as well as nearby streets. They are often colour coded for ease.

A more recent, but geographically limited series of maps are the Goad plans, made for insurance purposes from the 1960s and updated annually. They do not show residential properties but focus on principal commercial districts, chiefly high streets, labelling the shops by name. They are very useful for showing changes over time. With a scale of 40 inches to the mile they are more detailed than the OS maps. Large collections can be seen at the British Library, London Metropolitan Archives and the Guildhall Library, but those for a particular district should be found in the appropriate local studies library.

Guildhall Library. (Author)

Maps can be found in local record offices and libraries for the particular district that the institution covers. The largest collections can be found in a number of national repositories. Principal among these are at the British Library in their Map Room, which includes all the OS maps of the country, and at the National Archives (under WO44, 47 and 55). The Bodleian Library also has a substantial cartographic collection, including the first known map of Great Britain to show roads, the Gough Map of 1375. The Library’s map collection includes 1.25 million maps and 20,000 atlases (not just of Britain); 113 of the latter are maps of England from 1677 to 1835. Many of the older maps can be viewed online, of course.

Many record offices and record societies have published listings of maps in their collections, with commentaries on the maps and their makers. These are often illustrated with scaled-down illustrations of the maps in question. This can be a valuable method of ascertaining what exists before a visit to the record office is made – as well as checking their online catalogue, of course.

Maps are very useful for showing the built, or rural, environs, that your ancestors lived in. Even if you visit the place where they lived (which is recommended and discussed in Chapter 8), it is almost certain that the place will have altered to a lesser or larger extent. These maps will show what it was like at the time that they lived there. If your ancestors lived in the same village or town for a considerable period, the study of several editions of maps of the same district will show how it changed over time; perhaps revealing how a place became industrialised or/and how new roads and houses were built, and as garages were constructed and other forms of transport came to a district, such as railways or canals.