NEWSPAPERS

‘The Press, Watson, is a most valuable institution, if you only know how to use it’, as Sherlock Holmes commented to his friend in The Adventure of the Six Napoleons. There is such a great quantity of national and local newspapers in libraries and local studies centres that this sheer volume can appear forbidding. For an overview of newspapers, see www.cyndislist.com/newspapers.

There has been a newspaper industry, of sorts, in Britain since 1622, but the early titles were short-lived; the first to have a long life was The London Gazette, which began as The Oxford Gazette, in 1665, before being renamed in the following year. Initially it appeared twice weekly and then daily. It gave official announcements, but relatively little news as such. In 1702 The Daily Courant became Britain’s first daily (excepting Sundays) and was a single sheet of paper, double-sided. Most newspapers were published in London, but had a wide circulation elsewhere. The regional press developed in the eighteenth century, based in the major towns and cities, such as The Newcastle Courant in 1712 and The Northampton Mercury of 1720. Some cities had more than one newspaper.

One reason for the relatively limited array of eighteenth-century newspapers was that they were taxed. A stamp duty was imposed on newspapers in 1712. The tax was initially one penny for a folded sheet, but increased and had risen to four pence in 1815. The duty was reduced to a penny in 1836 and was finally abolished altogether in 1861. This resulted in a flood of new publications which could charge less now the tax was no longer due. This growth was also because of increases in both population and literacy. Newspapers probably were most informative towards the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century.

The content of newspapers has varied considerably over the centuries. Eighteenth-century newspapers contained a great deal of overseas news, mostly from Europe, much national news and a little local news, known as Country News. Indeed, local newspapers had little local news. Military, political and diplomatic news could take up much space. So did news of crimes and the verdicts of the Assize courts were usually featured when they took place. Births, deaths and marriages of the socially prominent would be reported, as would unusual events and strange deaths. Sport and fashion were rarely reported. Advertisements were a prominent feature, however, and could take up to half the space. These included adverts for property and other goods for sale and references to bankruptcies. Adverts can shed a light on local society. They can show farms for sale or for let, and sales of livestock and agricultural equipment. Shops selling farm essentials often listed their wares with prices. Markets were announced, with details of time, location, produce and other details.

There was also news of ships arriving at British ports and share prices. Letters from other parts of the country reporting on newsworthy events were a regular feature. Newspapers often pasted verbatim articles from other newspapers. They were rarely illustrated and their print-runs were usually modest.

Nineteenth-century newspapers tended to be longer. They also were usually far more detailed in their reporting of debates in Parliament and trials of serious crimes, for instance. As the century progressed they included other features. These were letters from readers, fiction, often in serial format, and an editorial on major events of the day. As sport began to be more organised, matches were reported, especially cricket and football, in the appropriate seasons. The doings of clubs and societies, churches and schools were other staples, as well as announcements for entertainments. Obituaries of individuals began to be printed, rather than just a line or two announcing a death as before. Personal columns listing births, marriages and deaths, paid for by the inserter, made their appearance. Local newspapers still often included national and international stories, presumably in the belief that readers would only buy one newspaper. Front pages would often be dominated by adverts (The Times maintained this custom until 1965). Again, illustrations were unusual. The Illustrated Police News broke new ground by its line drawings and lurid headlines from 1864. National newspapers now tended to be daily and appeared on Sundays, too. Local newspapers were invariably weekly, appearing on Fridays or Saturdays, but some were daily or twice weekly.

Adverts on front page of the Middlesex County Times, 1876. (London Borough of Ealing)

The twentieth century, with universal literacy now prevalent, saw a new breed of newspapers being created. There were new titles and old titles adapted, merged, changed their name or folded. They included more and more illustrations and some had prominent headlines. Features aimed at children and women began to appear. Print was larger and pages greater in number. National news and international news began to be banished from the local press, though letters pages often reflected controversies based on these events, as well as more local concerns. Towards the end of the twentieth century, some newspapers were made available free of charge and many appeared online. Local newspapers found themselves squeezed by rival news providers, though ever since the widespread availability of wireless and television news this had been an issue. Although there have been falls in circulation, the newspaper industry is still alive, but the local press is largely less informative and detailed in the early twenty-first century than it was a century ago.

Cities and towns have newspapers with their own name in its title; for example The York Courant in the eighteenth or The Keighley News in the following century. Small towns and villages may well not have a newspaper explicitly devoted to their own affairs, because of their small size; often a county may have one or more newspapers devoted to county affairs, such as the nineteenth-century titles, The Buckinghamshire Advertiser and The Middlesex County Times. Yet these newspapers often have a page or two which cover the towns and villages in that county and have a paragraph titled with that place’s news.

Newspapers were not all the same. Many had clear political standpoints, reflected both in editorials and in the letters pages. They can put across arguments for political reform at national or at local level, or bring to the readers’ attention perceived local abuses and issues, such as high rates, a polluted river or the cost of a new town hall. Local newspapers tended to have a bias, though not necessarily party political. This was especially the case if there was more than one newspaper for a particular district. Nationals also varied in their content, with some aiming at a low-brow readership and others at a more intelligent and educated clientele.

As with photographs and maps, newspapers for a particular district are usually to be found in the library or local studies centre covering that district. There are also two major national centres of newspaper holdings. One is the Bodleian Library at Oxford, with a collection of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century newspapers. The other is the British Library. There are two main collections here. One is in the Rare Books Room, and this is the Burney Collection of eighteenth-century newspapers on microfilm which can be very easily accessed by consulting the catalogues on the shelves and then going to the self-service microfilms which are very nearby.

The more substantial collection is the one which was held at the British Library Newspaper Library at Colindale in north London until 2013. It has now been moved to the main British Library site on the Euston Road, which makes life much easier as the trek from central London on the Northern Line can now be avoided. The collection includes most national and local newspapers published in Britain, and some overseas titles, since the seventeenth century. It is far from complete, however, with some newspapers being held elsewhere and some simply not having survived. Some of the major national and Sunday newspapers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are on open access, which is a great help. The vast majority, though, need to be ordered; some can take 70 minutes to arrive providing the order is made before 4pm; others may need longer (at least two days for paper copies), but orders can be made online prior to visiting. Some are viewed on microfilm and others in hard copy.

For those who are not able to visit London, electronic access to newspapers, usually for a fee, is an attractive option. Initially only a handful of national newspapers were available in this format, such as The Times (1785–1985) and the Daily Mirror from 1905. More recently, the British Library has been digitalising newspapers in the collection, and though only a small proportion have been digitalised, this is still a considerable number: see www.britishnewspaperarchive.co.uk. In both cases, the entire text can be searched by any search term desired and can be refined by dates. Any reference to the term in the press can be found; a name in an advert, in a letter, in a court case, anything. Access is through a subscription site (per month). Some institutions, such as the British Library, subscribe to such sites and so a researcher can view them there free of charge.

Apart from these, there are often card indexes or paper indexes to local newspapers held by local studies centres. These are very useful, but are inevitably limited compared to the electronic versions referred to above. Even the best indexes cannot include every single item that might be of conceivable interest to researchers. For example, every instance of petty crime or every property advert could not be included in such indexes.

The uses of local newspapers to the family historian are, perhaps, to an extent, obvious. There are obituaries, announcements of births, marriages and deaths. Prominent individuals and families, such as the nobility, clergy, gentry, local politicians, those in business, or particularly notorious ones (which could include those already mentioned) will also have their doings reported. Most people, though, rarely figure in newspapers.

But if your ancestors were, like most people, rarely if ever newsworthy, this does not mean that newspapers are of no interest to the family historian. Looking through a selection of newspapers for the town for the period that your ancestor lived in it, or at least a selection of them, gives an insight into their lives that no other source can give. Of course the information given in newspapers is often biased and certainly incomplete, though the latter can be said about any historical source. But they do offer an immediacy that no other source can offer, because they reflect facts and views of the time, unfiltered and unselected by historians.

These are the newspapers that your ancestors would have read, or perhaps, in the early nineteenth or eighteenth century, have had read to them (this often occurred in pubs). They may also have taken part in some of the activities described or have witnessed them. They therefore allow the family historian an insight into their lives, which helps them become more than names in census returns or electoral registers.

CASE STUDIES

Taken from The Buckinghamshire Advertiser, 1870.

HILLINGDON

PLEASURE FAIR- This event came off with the highest resplendency that naptha can convey last Saturday, and was the largest congregation of peculiarities that has been seen in the locality for many years. The weather was extremely warm, and the visitors very numerous, and all sorts of succulent and suspicious trifles of food and remarkable drinks were bought up with avidity from garish looking damsels and gipsy looking men. The compressibility of the human frame was studied in all the tavern entrances. Several distinguished caterers were present, one of whom gained renown by inducing small birds to execute very indifferent, though unnatural, exploits, another by exhibiting a prodigiously corpulent female, who had become expanded by some extraordinary physical process, whilst under a natural bower of elm trees several fair creatures could be seen displaying their sylphide forms on a platform of a circus tent, entrancing the rustic gaze with their serial gyrations. These were, in short, a variety of shows containing different wonders, but as it is reported that an adventure into the interior of such places is almost as ‘risky’ as sleeping with a Russian, we waived exploring their contents, an example, which we are proud to say, on the behalf of the proprietors, was not followed by humanity in general, who flocked into their depths both numerously and tumultuously. Extra police were in attendance, and all went off without mishap.

UXBRIDGE GAS

For some time past the inhabitants of Uxbridge have been endeavouring, but until recently without success, to discover the cause of certain noxious smells that have been prevalent in the streets, in our shops, and private houses. Now, however, there is no doubt that the various surmises indulged in were incorrect, and that to the impurity of the gas supplied by the Uxbridge and Hillingdon Gas Company may be traced the sole cause of the abominable stenches which have met us at every turn. To be satisfied upon the point, we have applied the simple sugar-of-lead-test and have found sulphuretted hydrogen present in the gas in large quantities. This is a state of things that should not, and must not exist; for surely if our tradesmen are content to pay a long price for the use of the article, they have a right, at least, to expect that they shall not be inconvenienced by being compelled to put out their lights, as we understand has been the case, at the time they most need them. The remedy is very simple. In proof of this latter statement we extract a few observations from an authority on the subject: ‘The gas and its accompanying vapours are next made to traverse a refrigerator, usually a series of iron pipes, cooled on the outside by a stream of water; there the condensation of the tar and ammonical liquid becomes complete, and the gas proceeds onwards to another part of the apparatus, in which it is to be deprived of the sulphuretted hydrogen and carbonic acid gasses always present in the crude product’. The neglect of the latter portion of the process would appear, therefore, to be the cause of the complaint the public can raise against the gas authorities, whose duty it imperatively is to at once adopt proper remedies, or, in other words, to give us pure gas with as little delay as possible.

Now, if you had an ancestor who lived in Hillingdon or Uxbridge in 1870 it is highly likely that they would have gone to the first event and have experienced the less amusing second. We cannot know what their opinion of the fair was. Clearly the journalist was not impressed, and made the proverbial ‘swift exit’ of journalists at moments of potential risk and embarrassment. Most people seem to have enjoyed it and relished a day on which they could partake of exotic entertainment to spice up what may well have been a pretty humdrum, routine rural existence. These extracts certainly help create a picture of events in the past which no other source can.

Editorials provide useful commentary on the state of local affairs in a given week. Take The Southall News in the winter of 1886:

It unfortunately happened, too that during the fortnight after the Christmas week, ie, during the school holidays, the penny dinner institution so nobly founded by W.F. Thomas, Esq., of Manor House, Southall Green was closed, so that the luxury of a hot mid-day meal for the children was not available to help out the meagre provision poor parents were able to afford for their families during the severe weather of the latter half of last week. That the penny dinner is appreciated as a boon may be inferred from the fact that as early as Friday last upwards of 500 dinner tickets had been purchased in anticipation of the re-opening of the institution, announced for Monday the 11th instant. That there are a few whom the dinners are intended to benefit who are not grateful is a matter of course, for such, too, ‘are always with us’.

The chief difficulty in the way of obtaining the dinners to lie in the fact that the poor have not the pennies wherewith to purchase them, and with the earth sealed against the spade, and all other out of labour rendered well-nigh impossible by the frost, their condition is saddening to contemplate, and while the frost lasts will daily become worse.

Sport is a common feature of the press, with usually a page or two’s coverage in each issue. While football or cricket, depending on the season tend to dominate, other sports are also reported, as noted in a July copy of The West Middlesex Gazette of 1930:

CYCLING

EALING CLUB’S RUN

Aylesbury, the venue of Sunday’s run by members of the Ealing Cycling Club, was reached in good time for lunch, after a halt at Amersham. A short run brought the club to Tring, where after a walk through Lord Rothschild’s Park and a visit to the Nell Gwynne monument, tea was served. The homeward run led through Chesham to picturesque Chorley Wood and Rickmansworth.

Tomorrow, after the open 50 miles T.T. for the John Bull Tyre Trophy, tea will be served at Oldfield’s, Maidenhead.

MOTOR CYCLING

MIDNIGHT SOCIAL RUN

There will be an all-night social run to-night (Saturday) by members of the West Ealing Motor and Motor Cycle Club, starting from the Ace of Spades Garage, Great West Road at 12 midnight. The first stop will be at the Devil’s Punch Bowl, Hindhead for coffee, then onto Houghton, Sussex, for breakfast. Members will then make for Goring-on-Sea to complete the day.

On the subject of printed matter, sermons were a popular type of publication in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as difficult as that may be to fathom now. A great many clergymen, not all of whom were well known, had sermons published, advertised in The Gentleman’s Magazine and elsewhere and being sold for sixpence. These might well be focusing on a particular political or religious event, whether national or local.

Given churchgoing was at a high rate in these centuries, your ancestor may well have been on the receiving end of these sermons, so to speak. Sermons were often bought by the literate and read out to their families. Many published sermons can be found at the British Library. You can search by typing ‘sermon’ and the village/town where your ancestor resided into the online British Library catalogue, and ascertaining whether these were published at the time of your ancestor. Of course, for each clergyman, only a few sermons were published and fewer survive. Furthermore, those that do may well not be representative of a parson’s output.

Ideally, one should read the newspaper for the town or village at the time when your ancestors lived there. That will give an impression of public events in that locality. Your ancestor may not, and probably will not, be mentioned by name. But it is likely that they may have participated in the events described and would certainly have been aware of them. They may or may not have read the same newspaper, depending on their literacy level, but newspapers were often read aloud in public places in the eighteenth century, for instance. This is a time-consuming process and so sampling may have to be resorted to, though this runs the danger of missing information that one would otherwise have gained.

However, the process need not be as lengthy as reading through whole newspapers. Since local newspapers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (and often beyond) covered national and international news, these stories can be ignored. Furthermore, newspapers often had specific headings for villages and towns in their remit and so all the news about a particular place would be under one heading and clearly marked with the name of that town/village. Newspapers tend to be organised in the same fashion from issue to issue, so if the national news is on page 2 then that can be passed over without delay, and if the news on particular places is on page 3, then only one page per issue needs to be scanned, and within that only one column. Editorials can often be omitted, if they are a commentary on national or overseas news, such as a war, but editorial comment often concerns local issues, too. Editorials often reveal the newspaper’s political and religious prejudices in a more obvious way than reporting of events, and so are helpful for a reader concerned with bias in the newspaper more general. Whether adverts, which often appeared on the front page, should be ignored is another question; probably not if your ancestors were in trade, because their competitors may well have advertised (as they may well have done themselves). And, of course, your ancestors may well have responded to the adverts by purchasing the goods and services in question.

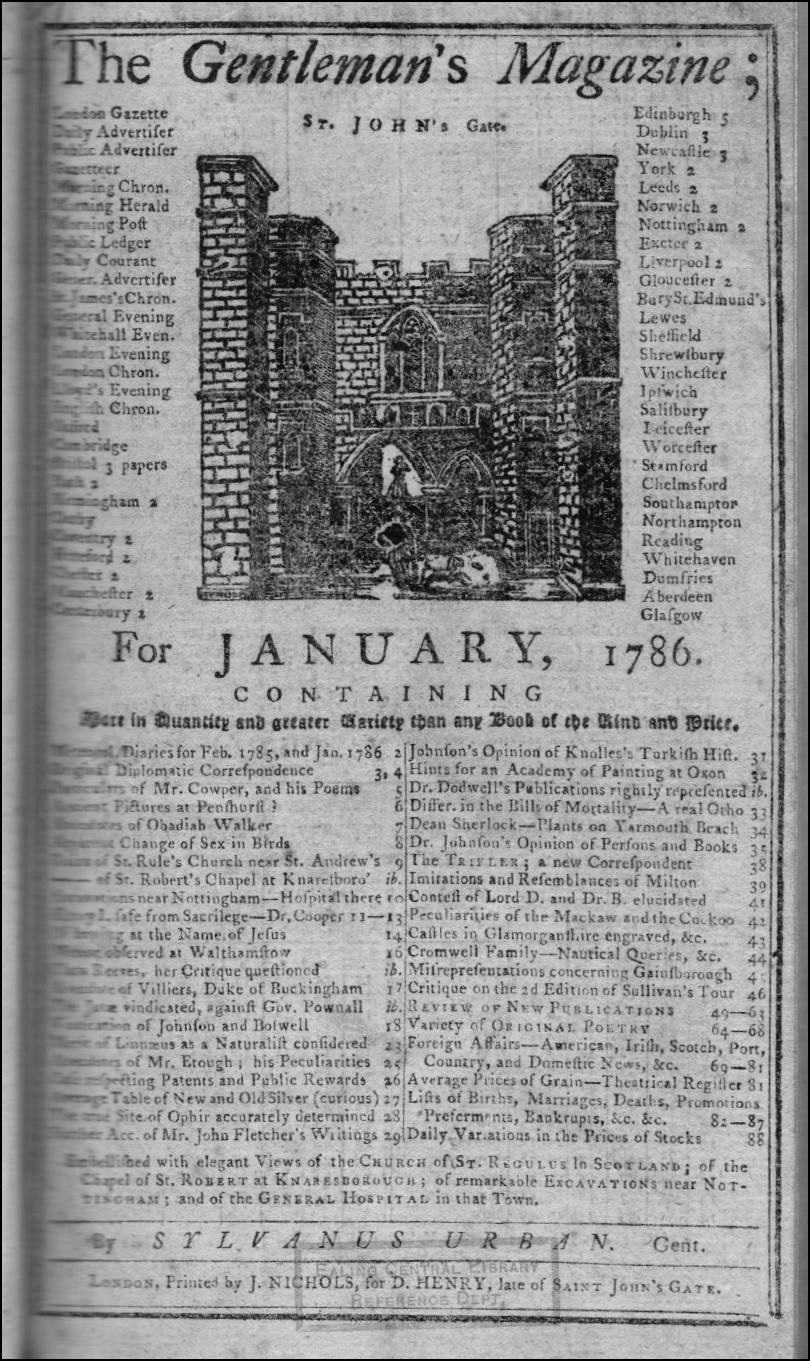

Gentleman’s Magazine, title-page (London Borough of Ealing)

There are also specialist publications which may be useful. First, there was the Political State of Great Britain from 1711–40 and The Gentleman’s Magazine of 1731–1868 (these latter can be seen, along with some other newspapers at www.bodley.ox.ac.uk/ilej but these full text copies are not searchable by keyword). They were arranged month by month and, as with eighteenth-century newspapers, covered national, local and international news in The Historical Chronicle. A couple of examples from this Chronicle from The Gentleman’s Magazine of November 1762 are as follows:

Wednesday 27 October

Early in the morning, the inhabitants of Norwich were surprised with a sudden inundation, which overflowed all the lower parts of the city, and laid under water between 2 and 3000 houses, and 8 parish churches. The flood continued all Wednesday, but abated on Thursday morning. It was 13 inches higher than the flood called St. Faith’s Flood in 1696, not so high as the great flood in 1646, by 8 inches; nor as St. Andrew’s flood in 1614, by 13 inches. In many of the streets, boats were plying to carry provisions, and assist the distressed. The water is thought to have risen about 12 feet perpendicular. The loss to the inhabitants is supposed to be near 10,000l.

Many people, in other places, suffered irreparably by the swelling of the waters on this memorable occasion, an imperfect account of which has already been given. It were to be wished, however, that our correspondents would transmit from the several places where the floods rose remarkably, an authentic account of the damages done in their respective neighbourhoods, the accounts hitherto published in the papers, being ether much exaggerated, or very defective.

Wednesday 3 November

A man about 60 years of age, stood on the pillory in Cheapside for a detestable crime. The populace fell upon the wretch, tore off his coat, waistcoat, shirt, hat, wig & breeches, and then pelted and whipped him till he had scarcely any signs of life left; but he was once pulled off the pillory, but hung by his arms till he was set up again, and stood in that naked condition, covered with mud, till the hour was out, and then he was carried back to Newgate.

They covered national news and the arts, economic and financial news, but also included genealogical information and topographical material. Some of the latter was republished separately by county in 1892, in a number of volumes, arranged alphabetically by county and then by parish. This included recording from monumental inscriptions and parish registers and descriptions of ancient and medieval remains. Prints and maps of buildings, towns and counties often appeared therein. These can be found on the open shelves of the British Library Rare Books room and the National Archives.

The built environment of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries can be studied via a number of contemporary journals. The Builder was established in 1843 and was a weekly magazine devoted to architecture and construction. Many public and private buildings feature, and each year it had an index to properties. It merges with The Building News (established in 1855), which had a similar remit. Country Life is well known for its articles and adverts for country houses, of varying sizes, but from its inception in 1897 has included articles about country districts which may be of interest. The works of civil engineers from sewers to bridges can be found online in The Engineer (from 1856) on www.gracesguide.co.uk. Despite its name, The Illustrated London News, initially weekly from 1842 but later monthly, featured articles about events elsewhere in the country and was always profusely illustrated (unlike many newspapers of the nineteenth century).

What newspapers often cannot do, though, is to describe everyday life. They are there to report news; events which are deemed out of the ordinary run of life’s events. So, for a village, reports of the population working on the land is unlikely to be reported except if there is some sort of celebration to mark the harvest being brought in, or if there is an accident to persons or property. The latter can often shed light on the ordinary processes, if, for example, an inquest had to be held on a farm labourer who was killed by machinery, say.

There is also a need for caution in accepting everything a newspaper reports as being accurate. First, newspaper reports about an event that happened in the past (at time of writing) should never be accepted at face value without checking sources written at the time of the said event. Second, reporting may not be comprehensive, so it is impossible to know what has been omitted. For example, letters from evacuated children reproduced in the press in the Second World War rarely contain any complaints, because a positive spin was required.

Newspapers as a source for events cannot be ignored by the local and family historian. How much time one spends with them is another question and that can only be decided by the researcher and the quality of the reporting. However, most people find reading old newspapers surprisingly addictive once begun and it is easy to become distracted from one’s main line of enquiry. It is common for stories and letters to continue over a number of issues and these can resemble chapters of a story that can make quite compelling reading.