MUSEUMS

Museums have existed since the seventeenth century in England; the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford being the first, with the British Museum following in the eighteenth century. Many more were created in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries throughout the country. Some are in public hands and some are owned privately. They are now seen as places of entertainment and discovery, rather than just as places of instruction and education which is how they were initially envisaged. Most towns and cities possess a museum. As with archives and libraries, some are of a national nature, for example, the National Army Museum (in London) or the National Museum of Media, Film and Photography (in Bradford). Some are centred around a particular type of collection, such as the Horniman Museum of natural history and ethnography in Forest Hill, or around a particular famous person, such as Apsley House, for the Duke of Wellington. Others, though, focus on the history of the locality. Some cover both particular subjects and the locality, such as the Museum of Rowing in Henley which covers the history of the town as well as that of the sport associated with it. These are of particular interest to the local and family historian.

County, city and town museums were originally the product of local municipal pride on the part of civic dignitaries, often to promote their town in comparison with neighbours and perhaps to increase tourism and local trade. Initially the collections were often haphazard and very esoteric. Stuffed birds and animals from Britain or elsewhere often featured, and other items collected from across the globe. Fossils and geological specimens were also included in these collections. This was because donations from the museum’s backers and friends were almost obligatory. Museums may be exist in purpose-built buildings but many are in a part of a council-owned building, which may be a former mansion or other historic building (sometimes in its own grounds).

The key difference between museums and libraries/archives is that the former are principally repositories of three-dimensional items, known as artefacts. There are usually other items as well, but artefacts are the primary components of the collection. Whereas most archives and libraries are free to use, many museums charge an entry fee, though there may be reductions for locals and season tickets are sometimes available. They are often open on Sundays and bank holidays, unlike the majority of archives and specialist libraries.

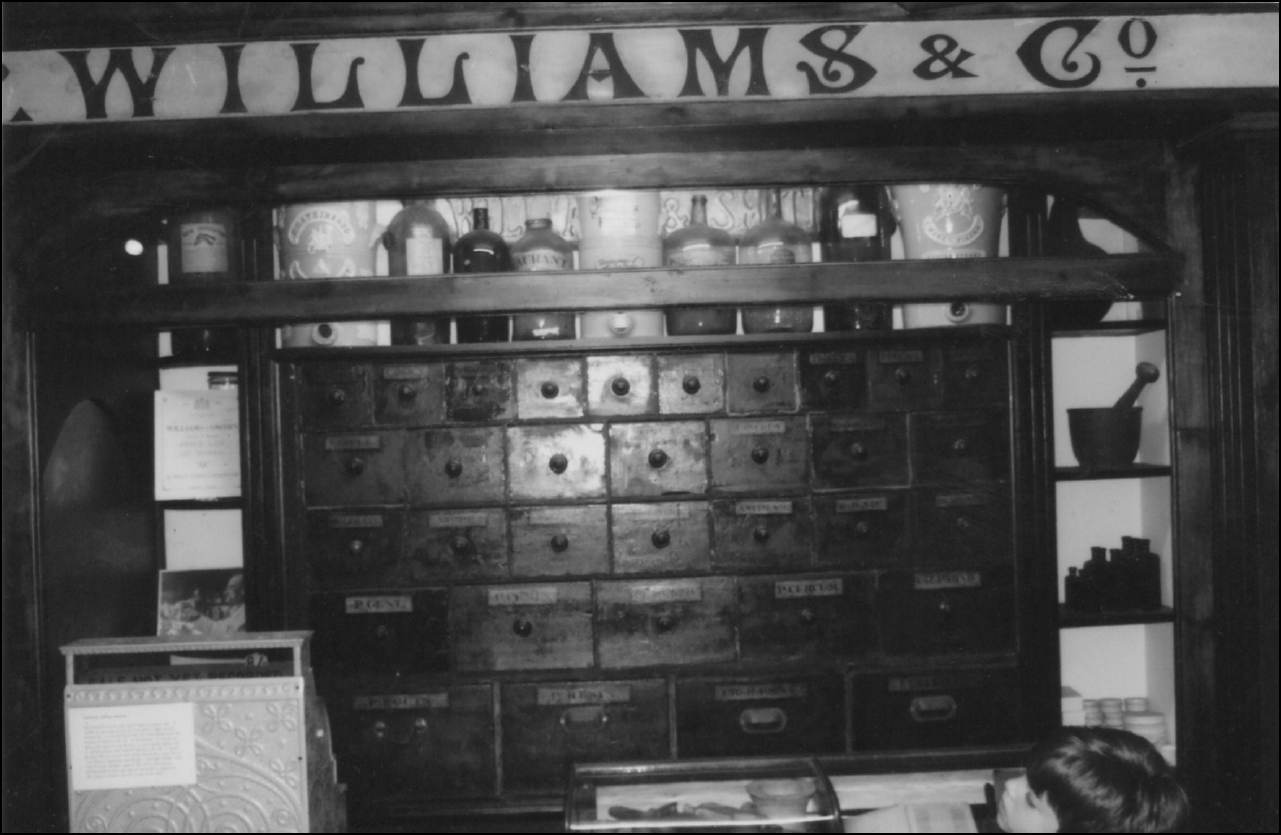

Shop front in Horsham Museum, 2014. (Author)

It is worth recalling that the exhibits in some museums predate those held in record offices and libraries. Museums often hold the archaeological remains of the district, which predate the written record by some centuries.

Until the late twentieth century almost all museum collections were located in glass cabinets or were roped off. Items there were to be seen and admired, not touched. This, of course, was for security and conservation as overhandling damages precious items. More recently, though, whilst these principles are not neglected, a more open attitude has been adopted. Often replicas are on open access and signs encourage their handling. Children, too, are often encouraged, and there are often parts of the museum specifically set aside for younger visitors, with appropriate toys and costumes. Film shows and audio tour guides are commonplace, too, and help guide the visitor around or give an introduction to the museum. Booklets can often be bought to explain the exhibits. These alternative formats are often used to provide information about the exhibits, replacing traditional museum labels which can be off-putting for many audiences.

As with archives and libraries, museum stewardship has become increasingly professional. Qualifications in curatorship are required and there are professional standards that most museums aim to achieve. Museums, as with archives, will have a collection policy, stating what they do accept and what they do not – a far cry from the rather haphazard collecting of the past. The policy may be determined by geography or by type of item. Items may be bought, donated or loaned from its owner. Professional conservators work to repair damaged items (often employed on a part-time basis or shared with other institutions).

Contents on display are not static. Museums often have special displays on particular topics, perhaps to commemorate an anniversary or highlight a certain feature of its collections. These displays will be temporary; perhaps lasting a few weeks or months, and may feature items from collections held elsewhere or from the public.

Museums should not be viewed merely as an entertaining experience for a weekend. What must also be realised is that the majority of a museum’s holdings are not on display but in storage. This is because there is insufficient room to display all their possessions. Yet there should be listings of the museum’s complete holdings. Often some of these can be viewed by appointment.

Museums offer the researcher an additional dimension of our ancestors’ lives that other sources cannot. They allow the viewing and, on occasion, the touching of artefacts. These may include agricultural and industrial tools and other material.

Of the national museums, the Museum of English Rural Life based at Reading University (a university which specialises in agricultural matters) should be mentioned, because it is the national museum for life and work in the countryside. It was founded in 1951 and its purpose is to record every aspect of English farming in particular. There was concern that the changing nature of agriculture would result in the disappearance of farming implements from usage. Apart from such tools and equipment, costume, veterinary equipment and evidence of country crafts are also collected. Along with three-dimensional objects, there is also a vast collection of photographs, oral history and written eyewitness accounts of life in the countryside. It also holds collections relating to wages of farm workers over time. In all these endeavours, help of country people is essential to provide information as well as exhibits.

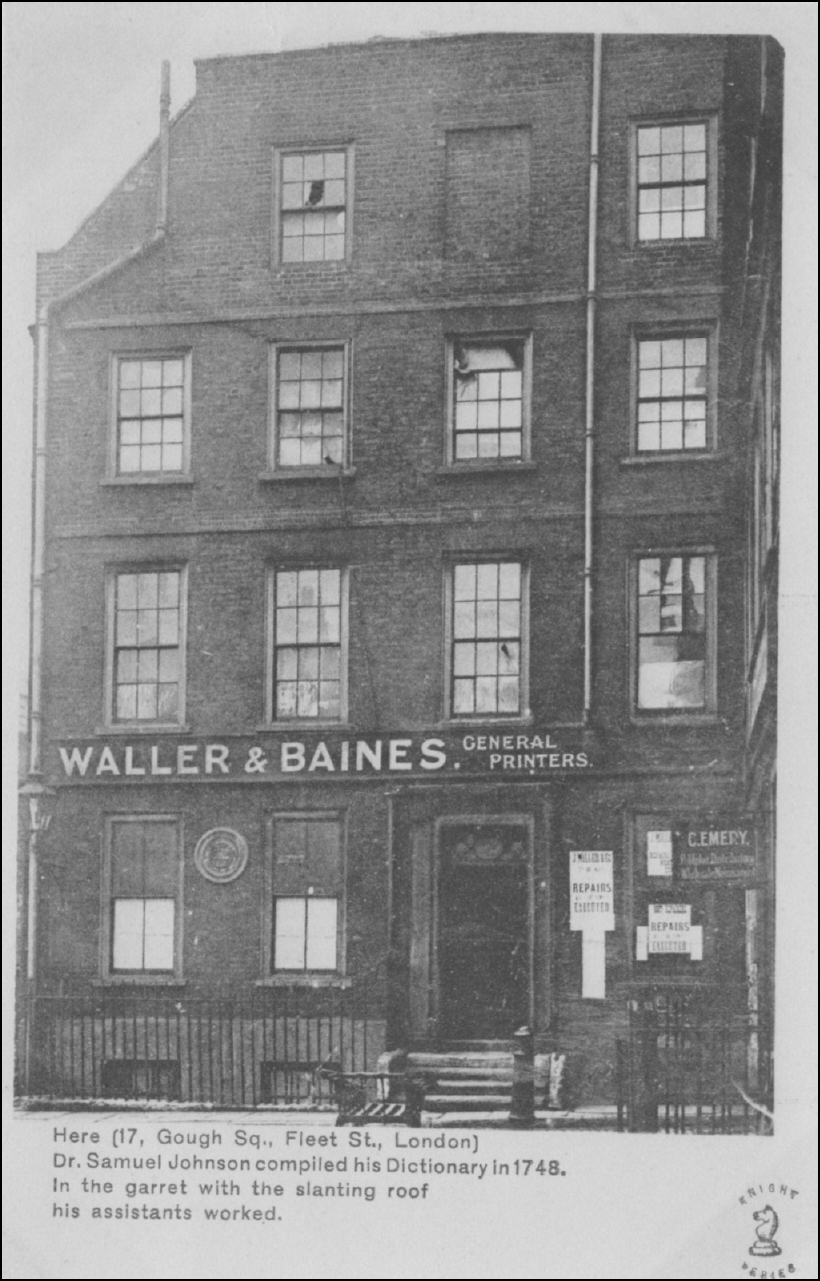

Dr Johnson’s House Museum. (Paul Lang)

The National Railway Museum at York is an essential place to visit, not only for railway enthusiasts but for anyone who has railwaymen among their ancestors. There is a large photographic archive there as well as technical records of trains and rolling stock. For those whose London ancestors worked for the railways or buses (or rode on them), the London Transport Museum is worth a visit. There are a number of trams, buses and underground trains which one can enter (at least in part). Another industry which created a great deal of employment for our ancestors was the canals. The Gloucester Waterways Museum and the Canal Museum in London have relevant collections, including examples of narrow boats and other paraphernalia associated with these craft and the people who worked on them.

Folk museums have existed in Britain since the 1930s. They aim to collect, preserve and make available items of little financial value, but which serve to illustrate a period of history of a particular part of the country. These items were once common, everyday objects which existed in large quantities. However, given technological advances, these are no longer used and so are in danger of being made extinct. Their display is enhanced if they are placed in a house of the period of which they are representative. These museums were first established on the continent and Britain was a late starter in this field.

One of England’s first was the York Castle Museum, which opened just before the Second World War, in the buildings of the now disused county gaol. It reproduces an early Victorian cobbled street in York with shop frontages and interiors, showing everyday artefacts and products. There are also craftsmen’s workshops with appropriate tools. The actual buildings therein are purpose-built, though the items on display are not.

Two other Yorkshire folk museums are the West Yorkshire Folk Museum at Shibden Hall, Halifax, and Kirkstall Abbey Museum near Leeds. Shibden Hall boasts agricultural and dairying equipment housed in a Pennine Barn, a collection of coaches and other vehicles and a number of craftsmen’s workshops. Kirkstall, in the 1950s, recreated a bygone urban environment, akin to the York Castle Museum, including a number of shops and workshops. These are a stationer’s, an apothecary’s, a haberdasher’s, a blacksmith’s, a wheelwright’s and many others. There is also a collection of agrarian tools, oral history recordings and photographs of old crafts and their practitioners.

Interior of Oxford Prison Museum. (Author)

Some museums are formed out of now redundant buildings and aim to tell the history of the building. One example is Oxford Castle Prison, which was the county gaol from the early modern period until 1996. Many of the cells with original furniture and fittings are still in situ, along with explanation boards about prison routine, famous prisoners and trials and reminiscences of former prisoners. For those whose ancestors were employed in the prison or were incarcerated there, this can help illuminate part of their lives (parts of prisons still in use can sometimes be accessed for a visit by appointment; at Wandsworth Prison the now defunct condemned cell is usually a highlight – it is a claustrophobic experience).

Museums also hold two-dimensional items, too, for many predate record offices (which, apart from the National Archives, are largely a twentieth-century phenomenon). They collected paintings, photographs, ephemera and even archival material at time when no other institution did so. These may well be unique and it is always worth making an enquiry.

Horsham Museum, 2014. (Author)

Museums sometimes have special events such as talks by experts, displays by re-enactors and children’s events, sometimes to mark specific anniversaries. These are opportunities to learn more and to talk to people who are experts in their subjects.

CASE STUDY

Horsham Museum

This is located in a sixteenth-century house in the town centre (Causeway House), once the home of the diarist Sarah Hurst, and has existed there since 1941, though it had moved from earlier sites, being founded in 1893. It has been run by the district council since 1974. It has three floors made up of 18 galleries. As with many museums, it had initially taken almost anything which was offered, which accounts for the ethnography collection, but in more recent times has had a more focused collection policy. The galleries include a room of children’s toys and games, one of shoes, another of costumes and one of ‘foreign objects’.

There are also rooms which focus on local history. These include rooms showing examples of local shops, local trade and industry (including saddles and ceramics), crime and punishment (including the door of a former police cell and a comb once owned by John George Haigh), and an illustrated history of the town. There are also nonpermanent exhibitions; in December 2014 these included one of Paddington Bear and another of photographs of the district in the 1920s.

As well as these items, there is also a library of local books, 1,400 posters, 6,000 photographs, 500 paintings and prints and over 26,000 documents dating from the twelfth century onwards. It has a special collection of papers of nearby Warham-born poet Percy Shelley and prints by local artist John Millais, including some of fighting game cocks. The museum has a shop selling books and souvenirs of local interest and has knowledgeable and helpful staff.

There is educational provision for schools, including tours by the education officer. For the elderly in residential homes there are reminiscence boxes which can be lent out to them. The museum’s website www.horsham.museum.org provides a virtual tour of the museum gallery by gallery.

While local history museums may have no documentation relating to your specific family, they will have material which can explain or evoke the life of your ancestors. The sort of help which a museum might give to the family historian includes dating family photographs from the clothing worn, or the style of writing on the back; photographs or paintings showing how your house, street or town looked in the past; plans or brochures for your house or housing estate; photos or other material relating to local schools; recorded memories of people who lived in your area or worked in the same occupation as one of your ancestors, information or artefacts connected with one of your ancestors if they were well-known locally; clothing of the type and date of those worn by your ancestors; tools, brochures or products from a business where your ancestor worked.

Since most museums have only a small staff and have most of their collections in storage, it is advisable to email or ring the museum first to ask if they have anything relevant to your enquiries and if these items are on show. If they are not, it will be necessary to make an appointment to see them.