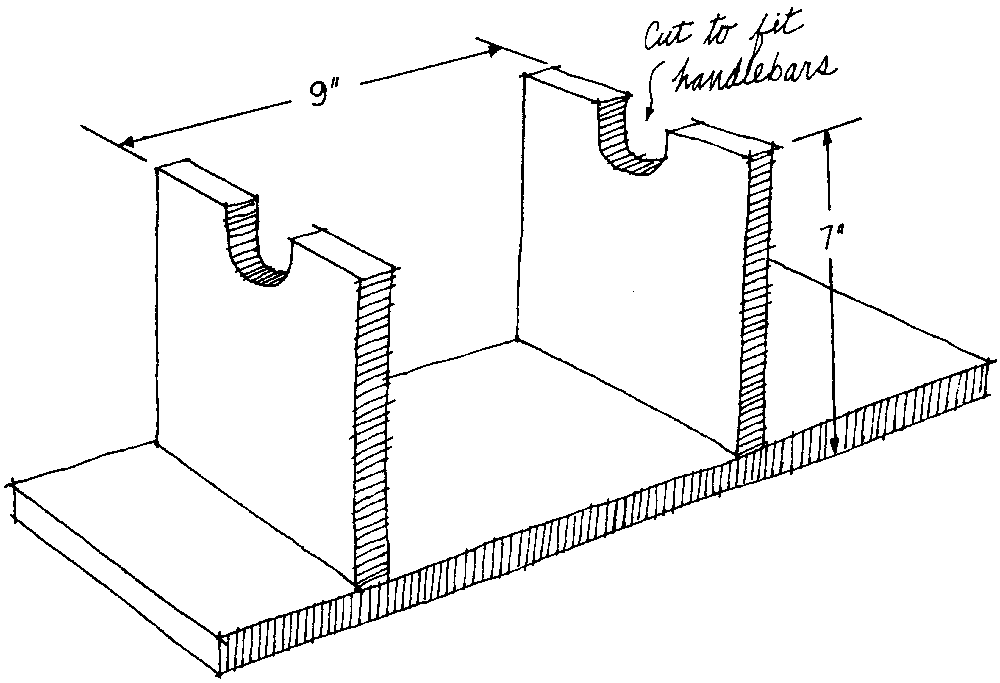

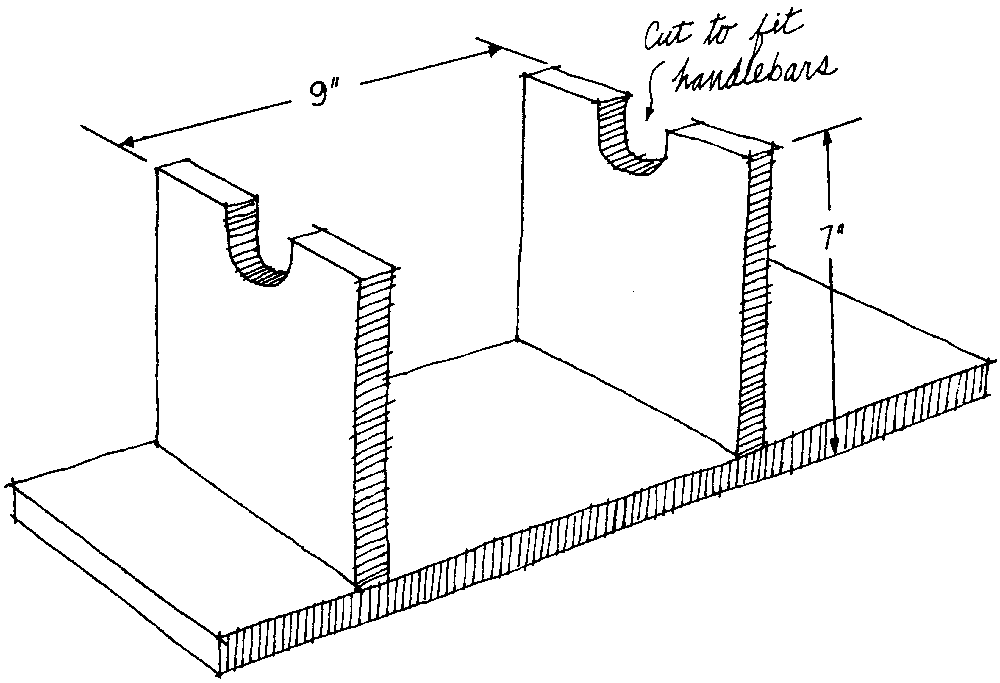

Figure 2.1

A simple bike stand. The bike rests upside down with the handlebars in the notches.

2

Bicycles, Tools, Equipment, and Clothing

The Bicycle Industry and Bicycle Shops

Before even considering buying a bicycle, you need to consider the large differences between bicycle shops and the changes in the industry over the last decade. It used to be that the American market was served by two classes of manufacturer and bike shop. There were the toy bicycles sold in department stores, auto parts stores, and local bike shops, and then there were real bicycles, generally made by European firms or by custom frame builders, sold through a few real bicycle shops. Real bicycles came in a range of types, from utility bicycles through bicycles for club cyclists to top-quality racing and touring bicycles. However, all the sporting bicycles had a strong family resemblance, and changes were infrequent. The higher end of the utility market was served by imitation racing bikes, which were not the best choice for utility service and were felt to be uncomfortable by people who rode infrequently. A real bicycle shop could get you parts for any real bicycle, because there weren’t many brands and models of parts and they all came from a few European manufacturers. The shop probably didn’t carry everything, but its personnel knew where to get everything. The mail-order firms carried practically everything, and many cyclists depended on them for parts, or even frame sets and complete bicycles, either from domestic distributors or from European firms.

The situation is different today. In many ways it is better, but in some ways it is more difficult. The market for real bicycles has expanded, diversified, and specialized. Two closely linked events signaled the change: Japanese firms began making bicycles primarily designed for the American market, and in the United States, the old heavyweight bicycle gave way to the lightweight and adaptable “mountain bike.” These events were linked by the arrival from Japan of wide-range, many-speed derailleurs, which made the mountain bicycle a practical proposition. Mountain bikes have seized a large part of the market. Low-end mountain bikes have replaced utility bikes almost completely, for they have a somewhat better design for that use than did the imitation racing bikes. The high-end ones serve an entirely new market of off-road cycling, as well as being used for on-road cycling (for which they are a poor design). The triathlon bike has evolved from the club bike into a specialized design that is suitable only for time trials. The road-racing bike has gone from 10 speeds to 16, and its components have improved. However, the touring bike has been neglected. Manufacturers have not yet installed wide-range derailleurs on touring frames; in fact, many have stopped making touring bikes entirely.

Frames of each design are now made in steel, aluminum or titanium alloy, and composite fiber, which all have different optimum sizes for their frame parts and hence for the components that fit them. And beyond this proliferation of designs and materials, an increased number of manufacturers are seeking to supply this increased market, with the European firms that used to supply the entire market now competing with new designs against the Japanese firms that made the most significant improvements in component design in two decades, as well as even newer American firms.

This discussion is important because buying a bicycle is not like buying a car. When you buy a car, what you order is what you keep; you don’t decide one day to slip a Jaguar engine into a Buick body. But you can make major changes in a bicycle because bicycle components are made to standards that allow interchangeability. You can easily switch derailleurs, wheels, brakes, hubs, headset bearings, bottom brackets and cranks, rims, handlebars, and saddles, as long as the new component is made to the same size standard as the old one.

There are so many different brands and models that the typical bike shop is overwhelmed. Most can carry only a small fraction of what is available. The mail-order firms are similarly overwhelmed. In the old days, they carried everything; though they carry more parts today, in some ways they have standardized to a smaller variety. If you want a new double-chainwheel crankset, the chainwheels are 42T and 52T; if those don’t suit you, you are out of luck. Chainwheels of other sizes are available, but only from specialist distributors with Internet catalogs. Therefore, once you become an enthusiastic and thoughtful cyclist and decide that you need special parts, you need to work with the kind of bicycle shop or Internet catalog that carries a wide variety of parts and whose personnel know how to identify, recommend, and order the parts that they don’t carry. Because designs now change rapidly, they must have the latest catalogs. Sure, you may start with another bike shop (perhaps one that is more convenient or that sells cheaper bikes), but once you become an enthusiast and know what you want, it is best to work with a well-informed shop.

There are three kinds of Internet retail suppliers. One kind sells all the items that you might find in a well-stocked bike shop but concentrates on the most popular items of each type. The other kind sells only bicycle parts but can supply all the variations that are made. A still different kind carries a wide selection of bicycle tools. Each of these companies will send a catalog upon request (some may charge for it). Often, consulting an Internet catalog will give you a better understanding of the range of parts offered than visiting one bike shop.

Bicycle Selection

There has been a lot of misinformation written about bicycle selection. Be cautious about everything that you hear or read. This chapter will stick to basic principles because there are too many details. I will consider bikes in the moderate and medium price ranges, because you are not ready to select a high-priced bike until you have had sufficient experience to decide how you want to ride and to develop your riding style. At the other end of the scale, stay away from low-priced bikes, which don’t run properly when new and cannot be adjusted to run any better.

Selecting a bicycle does not necessarily mean buying a new bicycle. Particularly if you are starting out or are resuming cycling after a long hiatus from riding, you might be considering borrowing a bicycle or examining your old one, to see if it would suit you until you learn more about your own cycling style and can buy with more assurance that you will get what you want.

In the moderate-priced field, there are three styles of bicycle: the utility bike, the mountain bike, and the road bike.

Utility Bike

1. Raised handlebars

2. Mattress saddle with springs

3. Generally either a three-speed rear hub or a five-speed rear derailleur without a front derailleur

4. Pedals with rubber treads

5. Medium-width tires

The utility bike is the cheapest of the three. It is intended for short trips, possibly with a load, by nonenthusiast users such as children going to school. It is heavy, durable when well made (although many are just cheap copies of better bikes), comfortable for short trips but uncomfortable and clumsy for longer trips. You can learn the elements of cycling with a utility bike, but once you have learned a bit, you will appreciate a better bicycle. Even for just cycling around town, its weight and inefficiency make it more difficult to maneuver in traffic.

Mountain Bike

1. Flat handlebars

2. Smooth saddle

3. Front and rear derailleurs producing 12 to 24 gears with a very wide range

4. Wide metal pedals (for wide shoes), or sometimes narrow pedals with either toe clips and toe straps or “clipless” foot retainers

5. Smaller frame

6. “Fat” tires, often with knobby tread for muddy surfaces, but obtainable with smooth tread for road cycling

Many people think that the mountain bike, with its comfortable posture and ride, its ability to jump curbs and potholes without damage, its wide-range gearing for the steepest hills, and its damage-resistant tires, is today’s utility bike. Maybe it is, but I think the mountain bike is not well suited for much of what we now consider utility cycling. Its main characteristics—the upright posture and the fat, knobby tires—produce excessive wind resistance and rolling resistance, making the mountain bike unsuitable for the longer trips that sprawling modern cities require.

Road Bike

1. Dropped handlebars

2. Smooth unsprung saddle

3. Front and rear derailleurs producing 10 to 24 different gears or “speeds” with only a moderate range

4. Pedals with metal treads, nearly always fitted with “clipless” foot retainers

5. Narrow tires (wired-on for most purposes, tubular for racing)

Without question, the road bike design is superior for all road uses. The dropped handlebar allows a choice of position: as high as the raised bar for slow riding and a change of posture, lower for better drive and lower wind resistance, and forward for better control over uneven surfaces and when braking. The smooth saddle supports the body without chafing the legs, and the absence of springs prevents power-robbing bouncing. The road bike design usually has the saddle further forward to place more of the rider’s weight over the pedals at the point of greatest effort, so the rider is lifted upward instead of tipped backward when pedaling harder. The narrow tires have low rolling resistance but, with modern materials, adequate resistance to damage. These are such great advantages that the road bike design should be chosen for all riding except strictly neighborhood utility riding or real off-road cycling.

Road bikes come in several different types for different uses. One use is road racing, with slightly different varieties for bicycle races and for triathlons. Another is one-day club and recreational cycling. A third use is for long-distance touring with touring loads. Too many of the present road bikes are designed as racing bikes; too little attention is paid to the club, touring, and serious utility markets. This is partly a reflection of customer demand and partly a matter of manufacturer conservatism. I think that many purchasers of what are essentially cheap road-racing bikes with club-cycling wheels would purchase club or touring bicycles if good ones were available at reasonable prices and if they understood the advantages of such designs for their particular purposes.

The number of speeds (gears) does not define the type of bicycle. A road bicycle may have from one to more than 20 speeds. Although most modern road bicycles have derailleur systems with 14 to 24 speeds, other types still exist. The one-speed fixed-gear bicycle (the pedals must turn whenever the wheels turn) once was the standard racing bicycle and is still advantageous for training. Some older road bikes have five-speed derailleur clusters with dual chainwheels, giving ten speeds. Still others use internally geared rear hubs, with three to seven speeds. A road bicycle is properly defined by the shape of the frame and handlebars and the type of wheels and tires, all designed for efficient cycling.

You should also consider what uses you will make of this bicycle. If you might cycle in the rain, you need a bicycle on which mudguards can be mounted. This installation requires adequate clearance between the tires and the frame, brakes that have the appropriate reach, and eyelets on the fork tips and the rear dropouts to which you can attach the mudguard stays. If you might carry loads, then you need an adequate rack. The best racks are custom-made and are mounted on brazed-on brackets, but reasonable clamp-on carriers are available.

The Good Utility Bicycle

If you do a lot of utility cycling, you may want to build up a good utility bicycle with the following attributes:

1. Shaped the way you like

2. High-quality components

3. Pedals that you like

4. Gearing adequate for your rides

5. Good lights

6. Strong racks

7. Mudguards (if you ride in the rain)

Sometimes such bicycles are made and sold, usually by specialist dealers, but because such bicycles have not been a market success, you may find that you need to build one up from used parts that you either already have or purchase secondhand. By the time you are ready for this, you will have sufficient knowledge and my advice wouldn’t be sufficiently detailed.

One complaint commonly made about the road bike, and a reason for advocating the mountain bike, is that the crouched-over posture is uncomfortable. The crouch, however, is not a characteristic of the road bike, but only of the particular handlebar position adopted by the rider. People who aren’t comfortable down on the drops, and who don’t feel much need to get there because they don’t ride fast or don’t often ride against the wind, should pull their handlebars higher, using a taller stem if necessary. Then they will have the advantages of three positions without an uncomfortable crouch.

Buy from a real bicycle shop, not a discount house, a department store, or an auto parts dealer. If there is no good bicycle shop near you, you probably would do better buying from a mail-order bicycle shop than from some other outlet. Buy a road bike unless you have specific intent to do off-road cycling. You won’t need and don’t yet have the cycling experience to select a first-class bike of any type, so get a compromise bike suited for club cycling, but one that will accept mudguards and a carrier rack. When you want a better bike, and have sufficient experience to know what you want, you can relegate this bike to around-town or rainy-weather service, so get one that is adaptable.

The current minimum price for the poorest reasonable ten-speed is $400. A much better machine can be bought for about $800. Get a diamond frame (man’s frame), not a woman’s frame, because it is more rigid, runs better, and is easier to resell. If you are very short, get a mixte frame, or consider a bicycle with 650B wheels and a short top tube (so you don’t have to stretch for the handlebars).

Double chainwheels with a 10- or 12-tooth difference, used with a sprocket cluster ranging from 14 to 26 teeth, are not ideal but acceptable to start with. The cranks will be light alloy, held to the axle with nuts or bolts and requiring a matching extractor tool to remove. A pie-plate chainwheel “protector” is unnecessary and may be removed. Instead of holding the chain on the chainwheel, it sometimes jams the chain; its only function is to protect your trousers, and trouser bands do this better.

With a bicycle of this class, you probably can’t specify the gearing system you want (sprocket and chainwheel sizes, with derailleur to match). If you can, then consult chapter 5 before doing so.

Derailleurs are the components that made most spectacular progress in the 1980s. All those that are now made work extremely well over their designed ranges of gears. In the old days, one had to shift with great care. The levers moved freely (without indexing). Shifting performance changed as the chain wore, and shifting performance at the rear changed depending on which chainwheel was in use. Often one shift required two motions, one to make the chain move to the desired sprocket and a second motion in reverse to center it onto that sprocket. Nowadays, the major manufacturers offer indexed shifting. Each lever has a particular click-stop position for each sprocket. Move the lever until it stops at that position and the derailleur automatically moves the chain to that sprocket. However, the manufacturers also say that to make the indexing system work properly, you must use their own chains and sprockets with their derailleurs, and only for the range of sprocket and chainwheel sizes that they specify. You need not follow this advice, because economical substitutions are now available; check the catalogs and ask for advice on which parts work together.

The derailleur levers must be either on the down tube or at the handlebar ends. Levers on the top tube or on the handlebar stem are too likely to stab your crotch in case of a collision, and levers on the handlebar stem affect the steering when you shift.

The wheels will have 700C-size rims and tires, or 27 × 11/4-inch for cheaper bikes. 700C is the better choice; good 27 × 11/4-inch tires may well become hard to find. These wheels will be built on light-alloy hubs that probably have quick-release levers (so that the wheels can be removed from the frame without a wrench). You don’t really need quick releases with these tires, because you need to get out your tools to change a tire tube anyway, but they are a convenience if you often remove the wheels to carry your bicycle in a car.

The wheel rims ought to be of light alloy, both to save weight and to allow the brakes to work well in rain. There is no reason to buy a bike with chrome-plated steel rims today. Because wheels and tires have the most effect on the bike’s rolling friction, buy good wheels. And because flats are the most frequent repair problem and always happen on the road, get rims and tires that are easy to repair. Buy wheels with hook-bead rims rather than Welch rims (see chapter 8), and buy high-pressure tires with steel bead wires.

The brakes can be sidepulls with a center pivot or centerpulls with two pivots. Each brake must have a cable-length adjuster. Some makers skimp on these, but they are easy to install. Auxiliary brake levers are undesirable; most kinds reduce the operating stroke of the lever, they generally cannot be fully applied, and your hand position when you are using them does not provide the steering control you need while braking.

If your tires are much wider than the rims, brake quick releases will let you replace a wheel even when its tire is inflated. If you need these, get brake levers that have the kind of quick release that cancels automatically the next time you use the brake.

The saddle must be smooth leather or plastic, without springs. Some people like a suede finish.

The handlebars must be of the “dropped” (i.e., downturned or “racing”) type.

What is most important is that the bicycle fit your size, build, and style of riding. The trouble is that you cannot tell, without lots of experience, what is exactly right for you. So start with an average bike of the correct size. The size should be such that you can just straddle the top tube with both feet flat on the ground. This will enable you to make safe traffic stops.

Testing a Bike for Purchase

With the help of the salesman, get the bike adjusted before you buy it, and test it before you accept it. It should track straight with your hands off the handlebars, without your having to lean it sideways, and you should be able to steer it by leaning about equally to each side. Turn the bike into sharper corners with your hands on the handlebars, to check whether it feels the same for right and left turns. If it meets these tests, it is probably near enough to correct alignment; if it doesn’t, it may have a bent frame.

Check each bearing for smooth rolling without perceptible looseness—this includes the bearings in the wheels, the cranks, the pedals, and the steering head. Check the brakes by squeezing the levers hard. The levers must not reach the handlebars, the brake blocks must touch the rims squarely, and on centerpull brakes neither of the cable hooks must get within ½ inch of its cable housing stop.

While riding, shift the rear derailleur from high to low and back again, using one chainwheel and then the other. In particular, check that the chain will shift into and out of the large-chainwheel-and-large-sprocket combination, and that in the small-chainwheel-and-small-sprocket combination the chain is still tight on the lower side. If the bike has a triple chainwheel, the derailleur may not take up all the slack in the chain when the chain is on the smallest chainwheel and several of the smallest sprockets. In this case, you must never use these combinations. (If you inadvertently shift into one of these, the chain can jump off, it is difficult to shift out of that gear, and it is possible that trying to do so will damage the rear derailleur.)

If you are unfamiliar with bikes, learn the tests in this book on someone else’s bike before visiting the bike shop. (See also the section “Sensitivity and Bike Selection” in chapter 3.)

Tools

The correct tools will enable you to do the easier and more frequent repairs. You should carry with you the following items:

1. A 6-inch adjustable-end wrench (crescent wrench)

2. A dumbbell-shaped multisocket bicycle wrench, or a set of ¼-inch-drive socket wrenches with T handle, in metric or inch sizes to fit the nuts on your bike

3. If you have adjustable hubs, flat steel open-end bicycle cone wrenches to fit them

4. A spoke wrench of the correct size for your spoke nipples

5. A screwdriver with a stubby narrow blade, particularly for adjusting derailleurs

6. Allen (hex) keys to fit the socket-head screws on your components.

Some equipment requires special tools, which you should add to this set if necessary. A 10-mm box-end wrench can be bent to fit Campagnolo seat posts, and an 8-mm socket wrench is needed for Campagnolo handlebar shift levers. One firm offers a tool that combines an adjustable wrench, a crank bolt socket, a chain riveting tool, Allen keys, and a screwdriver. This may be a compact solution to the problem of too many tools in the bag.

After you have collected the tools that you think you need to tighten every bolt, nut, and screw, go over every bolt, nut, and screw to make sure that you actually have the matching tool, and also that you are not carrying tools that your bike doesn’t need.

You should also carry a tire repair kit consisting of the following:

1. A pump on the bicycle with the adapter to fit your type of valve, Presta or Schrader (short fat pumps are for low-pressure fat tires, and long slender pumps for high-pressure narrow road tires)

2. Two tire levers, at least one of them with a hooked end (three levers if you use fiber-bead tires or if your tires fit tightly to the rims)

3. Two tire boots of cotton denim, cut to approximately 1 × 2-inch and precoated with contact cement

4. Abrasive cloth about 1 × 2 inches, or sandpaper glued to a tongue depressor

5. Six tire patches

6. A tube or bottle of rubber tube patching cement

7. A foot of ½-inch adhesive tape or duct tape, rolled up

8. A spare inner tube

9. A small bottle of contact cement (the flammable kind with toluene as the solvent) with the cap wrapped in friction tape for easy unscrewing

Users of tubular tires should carry a pump and two spare tires.

For home repairs and maintenance, you will need the following:

1. An inexpensive bicycle workstand, which can be made from two pieces of clothesline or a few blocks of wood (described shortly)

2. Two fine-tipped oil cans

3. And old or cheap 1-inch paintbrush for cleaning

4. A baking pan, about 9 × 13 inches, to catch drippings

5. Jars or foil cups for parts, solvents, and the like

6. Rags for cleaning

7. A quart of SAE 90 automobile rear axle (hypoid) oil

8. A quart of white gasoline (Coleman fuel)

9. 1–4 quarts of kerosene for cleaning

10. A small can of grease (auto chassis grease, not wheel bearing grease)

11. Talcum powder for dusting inner tubes before returning them to their casings

12. Plastic rubber (Duro) or rubber material (Devcon) for filling cuts in tire treads

13. Contact cement (Weldwood) (the brown, flammable type with toluene solvent, not the white nonflammable type emulsified in water)

The following tools will enable you to repair almost any component other than the frame. They are tools for occasional use—not as easy to use or as reliable as the ones that professionals use, but much cheaper.

1. A chain riveter

2. A homemade bottom-bracket fixed-cup extractor (see chapter 11), or the special tools required for your brand of bottom bracket set (see item 10)

3. A 12-inch adjustable wrench for headsets, freewheel removers, and bottom-bracket cups, or fixed wrenches to fit

4. Two chain wrenches for disassembling the gear cluster, or other special tools that your cluster requires

5. A freewheel remover to fit your freewheel

6. A homemade cluster holder (see chapter 16)

7. A crank extractor for your type of cranks

8. A socket wrench to fit the crank bolt

9. For cottered cranks, a homemade crank support and steel punch

10. For cartridge-type bearings in hubs or bottom bracket, the appropriate tools for disassembly and reassembly

11. Wire cutters

12. A soldering iron and supplies

13. An 8- to 10-inch flat file for filing the ends of brake and gear cable housings, crank cotters, and so on

14. A hammer

15. Wood blocks to protect the headset during installation

16. A foot-long ½-inch-diameter aluminum bar for use as a drift

17. A homemade rim jack (see chapter 19)

Your work will be easier if you have access to a workbench, a bench vise, a grinder, and a wheel-truing stand.

Your workstand need not be complicated or expensive. Its purpose is to hold the bike’s wheels off the ground so that you can do effective maintenance and repairs. You cannot adjust derailleurs without having the rear wheel free to turn. You cannot true wheels without having the wheel free to turn, or having a wheel-truing stand.

The simplest workstand consists of two pieces of clothesline hung from rafters. The rear piece has a loop about 6 inches across tied in its end to slip around the nose of the saddle. The front piece has a wooden toggle tied into it 2 feet above the end and a small loop tied in the end. The end is passed under the stem just behind the handlebars, and the loop is hooked over the toggle. Spacing the two ropes farther apart than the saddle-to-handlebar distance reduces sway. This setup is best for cleaning, because the dirty drippings from the chain fall clear as you clean. It is also a good way to store a bike so that it won’t be knocked over and the tires don’t get flattened if the bike is left standing for a long time.

The next simplest workstand puts the bicycle upside down. Cut six pieces of 2 × 4-inch lumber about 6 inches long, and pile them in two piles of three each. Glue or nail them together. Get a clean cloth about 12 inches square. Arrange the bike upside down with the saddle on the cloth and the flat parts of the handlebars resting on the blocks. The upside-down position is best for wheel truing. This workstand tends to slip. A better one is made in one piece (figure 2.1). Cut a crosspiece about ¾ × 4 × 16 inches and two uprights ¾ × 4 × 7 inches. Cut a notch to receive the handlebar into the end of each upright. Mount the uprights by gluing and nailing, or screwing them onto the crosspiece 9 inches apart. Use this stand just like the previous one.

Figure 2.1

A simple bike stand. The bike rests upside down with the handlebars in the notches.

Another simple, commercially available workstand has a hooked top and two legs. The top fits around the down tube just ahead of the bottom bracket and the legs extend rearward so that the bike rests on the front wheel and the two legs of the stand, leaving the rear wheel raised free for derailleur adjustment.

A good way to store a bike indoors is to put a big hook in a wall 7 feet off the floor, with the hook parallel to the ground, or into the ceiling 12 inches from a wall. Catch the rim of the front wheel on the hook and let the bike hang vertically as if it were trying to climb the wall. This is what is done on European trains.

Spare Parts

Even though parts that require frequent replacement are normally available at bike shops, if you have the part at home, you can make a replacement the same day. If a part is difficult to obtain, having one on hand may prevent a lengthy delay in getting your bike on the road again.

These are common wearing parts that you should keep at home:

1. Brake and gear inner wires

2. Brake cable outer housing

3. Brake blocks

4. Tire inner tubes (several)

5. Tire outer casing (one or more)

6. Rim tape

7. Handlebar tape or other covering

8. Chain

9. Spokes and nipples of the correct lengths for your wheels

10. Bearing balls of the common sizes, if any of your components have bearings that use them; many modern components use cartridge bearings instead

11. At least one spare rim and sufficient spokes to build a new wheel (if you build your own wheels)

Clothing

You can ride in almost any clothing, but the active cyclist wears clothes that meet the special needs of cycling. Earlier editions of Effective Cycling carried instructions for repairing and even making shorts, because proper cycling clothing was often difficult to obtain. Nowadays, the cycling clothing that is readily available is generally far better than any that was available before. Owing largely to improvements in fibers and fabrics, cycling garments fit better, are more comfortable despite sweat or cold, wear longer, and wash cleaner.

In warm weather, the cyclist wears cycling shorts and jersey. The shorts fit tightly and are long enough to extend below the saddle edge, and have a crotch lining made of special fabric. This fabric is the best material to protect the skin against the pressure and friction of saddle contact, so the shorts are worn without underwear. The shorts have no pockets because their contents tend to shake and rattle against the moving thigh. The shorts are made of stretchable synthetic fabric. They used to be made in black only, partly to conceal the stains of saddle contact, chain oil, and dirty hands, but nowadays practically any color is acceptable because the material washes much cleaner and because many cyclists use plastic saddles that don’t stain the shorts.

A cycling jersey is a tight, short-sleeved shirt with a zippered, round neckline. It is long enough to reach well below the waist (so it covers the waist when the wearer is in riding posture), and it has pockets over the lower back, and maybe on the chest also. Though high-quality jerseys are now readily available from many sources, the designs suffer from excessive emphasis upon racing and well-supported large rides. Front pockets are left off because they create wind resistance and aren’t necessary when food is handed up to you or food stops are frequent. Today, if you feel the need for more pockets you sew additional front pockets into a jersey that doesn’t come with them.

For cooler weather, the cyclist adds arm and leg warmers—tight-fitting “sleeves” extending from wrist to jersey sleeve, and from ankle to shorts—that can be added or removed without disturbing the jersey or the shorts. These are held up by elasticized tops backed up by patches of hook-and-loop fastener or safety pins. The fabric is the same as the jersey’s. For still cooler weather, the cyclist wears a sweater and a nylon-shell windproof jacket or a “warmup” suit with tight-fitting zippered calves.

Touring cyclists usually wear normal shorts or trousers, shirt, and sweater, though keen tourists in cool weather may wear specially made trousers with tight-fitting zippered calves and the same crotch lining used in cycling shorts. Sewing such a crotch lining into normal trousers is easy, and the linings are available at better bike shops. Permanent-press polyester knit slacks in dark colors enable anybody to ride to work and appear neat shortly after arrival. (But some polyester knit fabrics snag easily and are destroyed in a few miles—and I cannot tell you why.) With long trousers, always wear trouser clips or bands on both legs to protect the fabric from chain grease and abrasion.

Cyclists can be subjected to simultaneous extremes of temperature, wind, humidity, and effort. Three minutes after the intense and sweaty effort of climbing the sunny, windless side of a pass, a cyclist may be sitting motionless and descending the shady side at 30 mph against a 20-mph wind. Cyclists must anticipate such extreme conditions by carrying several layers of clothing that can be worn separately or together, with a light windproof jacket for the top layer when necessary. The chronic problem is getting too hot and sweating and then becoming wet and cold; that problem is best solved by any of the several varieties of good wicking material. Keep your clothes adjusted so that if you sweat it will evaporate quickly, particularly around the trunk.

Polypropylene fiber is particularly good for cold-weather underwear. It transmits the water vapor of your sweat without absorbing it, so it remains comfortably dry and warm even when you sweat. However, polypropylene has insufficient durability for outer garments. Jerseys made of it are very comfortable, but show pilling and look old after one month’s wear. (Polypropylene is very flammable; be careful when warming up near open fires.)

In cold weather, a cyclist’s fingers are exposed to the wind and grip cold brake levers. Two-layer protection is required, with warm mittens inside windproof outer covers. Foam-lined skiing gloves are also good—the foam stays warm when wet. A cyclist’s toes are similarly exposed, requiring warm socks inside windproof shoe covers.

Cycling shorts and trousers must not be washed in detergent. When they are, the detergent residues get rubbed into the skin and cause sores that resemble chemical burns. Use only pure soap, or even no soap, when washing by machine.

Gloves

For safety purposes, cyclists often wear fingerless gloves with leather-padded palms and cloth-mesh backs. The leather palms serve two purposes: they cushion the hands against the handlebar to help prevent numb fingers, and they provide protection in a fall.

Shoes

Touring shoes are much like running shoes with stiff soles (and sometimes a molded groove across the sole to accommodate the back bar of a conventional pedal). They fit double-sided pedals and pedals with clips and straps. They are intended for situations in which the user expects to do considerable walking, doesn’t want to change his shoes, and doesn’t desire the highest cycling performance.

Racing shoes with clipless cleats are like those with old-fashioned cleats, except that their cleats are designed to fit one or another of the clipless pedal systems. They can be used only with the appropriate clipless pedal. Rubber oversoles are available for some styles of cleat; these clip over the cleat and permit walking in some comfort and with less chance of slipping.

Mountain cycling can be done in any kind of shoe or boot, but special mountain cycling shoes are available. These are like running shoes with a cleat for the mountain bike’s clipless pedal inserted flush within the sole, so they can be used for walking, scrambling over rocks, and cycling. Similar designs are intended for the kind of touring that includes walking around towns or exhibitions.

Shoes must be both wide enough at the toe and long enough for plenty of toe-wiggling room. But sufficient room does not guarantee comfort. A shoe should be shaped and the closures adjustable so that it keeps the foot back at the heel of the shoe, allowing the toes room to wiggle. The motion of pedaling always tends to push the feet forward in the shoes until the toes touch the ends. That results in exquisite pain, like a knife through the toes, after about three hours of riding. To prevent this, the shoe should be wedge-shaped, with the top sloping down toward the toe. When you tighten the laces, your foot will be held back by the shape of the shoe top—not by the toes. The extra length is useless if your toes push forward against the tip. One method of reducing tension across the toes while maintaining it against the body of the foot is to lace only the top half of the shoe, letting the toe part expand. The new shoes with several straps secured with Velcro are faster to get on (important to triathletes) and allow different tensions in the different straps for the best combination of comfort and security.

Foot Retention Systems

Cyclists who do any amount of sporting cycling end up wanting to use some kind of foot retention system to prevent their feet from slipping off the pedals or just plain losing the best position. But you don’t start cycling with a foot retention system.

Using shoe cleats is another of those cycling actions that look dangerous and difficult but aren’t. Cleats have so many advantages that once you learn to use them, you won’t like riding without them. When I go to a meeting, I ride there in my cleated racing shoes and carry a pair of lightweight indoor shoes.

Cleats enable you to drive forward at the top of the pedal circle and to pull back at the bottom, distributing your effort among more muscles and making your drive smoother. Cleats also keep your feet pointing straight in the pedals, so that even when you are dead tired, your feet don’t slip and your ankles don’t bump against the cranks. Some form of foot retention and location is indispensable for developing the smooth, supple leg and ankle action that will carry you many miles at high speeds.

The oldest and simplest system is the toe clip and toe strap. These can mount on the plain rectangular double-sided pedal, so you learn with the plain pedal and then attach the clip and strap. The clip extends forward and up over the toe of your shoe and then back as far as the center of the pedal. The strap goes through slots in the pedal and then up through a flat loop at the top of the clip, and it has an easy tightening, quick-release buckle. You can use these with any shoes. If you wish to start this way, buy pedals, clips, and straps at one time, and make sure that the pedals will accept the clips and straps. Once you are comfortable with plain pedals, fit the clips and straps and learn to use them. Before 1980, some cyclists added cleats to sporting shoes used with clips and straps, but nowadays they use one of the modern foot retention systems.

“Clipless” systems provide a more rigid retention system that provides greater security for sporting and racing cycling. In general, the cyclist steps into the retention clip. Then, when he wants out, he disengages by twisting his heel outwards. These systems employ clips built into the pedal and cleats attached to the shoe, and, generally speaking, the set must come from one manufacturer.

Regardless of other differences, there are two general shapes. One shape has cleats extending well below the sole of the shoe, so that walking has to be done on the hard plastic cleats (the same was true of the old-fashioned aluminum cleats that used to be used with clips and straps). Racers and pure road cyclists tend to use this shape. The other shape has the cleat inserted into the sole of the shoe, so that walking can be done on the sole of the shoe instead of on the cleat. Mountain bikers tend to use this shape. I have used both shapes and find them equally easy for cycling use. By the time you are ready for a clipless retention system, you can probably decide which shape would be better for you.

Helmets

Helmets are a controversial subject. A bicycle helmet is designed to provide pretty good brain protection against a fall from your bicycle in which you hit your head on the road surface. However, most falls are sideways falls in which the impact is taken by thighs, hips, and shoulders. I suspect that the proportion of headfirst falls increases with the speed of cycling. If so, this means that helmets provide a greater amount of risk reduction for cyclists who habitually ride fast. Helmets are not and cannot be designed to provide brain protection from impacts by motor vehicles traveling at typical speeds.

Still, three-quarters of the deaths and probably three-quarters of the permanent disabilities among bicyclists are caused by brain injury. Protection against brain injury requires a helmet strong enough on the outside to resist puncturing by rocks and crushable enough on the inside to slow the skull gradually when hitting the ground. Crushability is the more important characteristic, and it requires at least half an inch of rigid foam. Choose a helmet that fits your head closely in a comfortable way from among those with a strong outer shell and a thick lining of rigid crushable foam. Buy only a helmet that is marked as passing the appropriate tests: ANSI or Snell in the United States, other names elsewhere.

Helmet wearing is politically controversial. Very large numbers of slow European cyclists operate without helmets, and there is no record of a high death rate. Mandatory helmet laws reduce cycling. The strong emphasis on the need for helmet wearing serves to exaggerate the fear that cycling is inherently dangerous and the belief that helmets provide great protection.

The most important first safety measure is riding so that you are less likely to get into accident situations. Watchfulness and skill in escaping them is the second. But when all else fails, you need to reduce the injury. Helmets are a relatively cheap investment that provides partial protection against the worst kind of injury to cyclists, brain injury. If you do a lot of cycling, particularly fast cycling, helmet wearing may be advisable.

Saddles

Much that has been written about saddles is merely folklore, lacking even the validity of careful individual testing, much less any measurement during use by large numbers of cyclists. The scientific work that has been done is insufficient to prescribe how to fit a saddle to a cyclist. However, the criterion is obvious: the saddle that is comfortable on long rides is the right saddle for you. As with shoes, some people are comfortable with one shape and others prefer a different shape. However, if you know the principles and recognize the misconceptions, you can find a saddle that is comfortable for you with less pain, time, and expense than you would incur otherwise.

A really bad saddle can be detected immediately or on a short ride. Cheap bicycles generally have painful saddles, not so much because they are badly made as because they are badly designed. Such saddles are rarely offered by good bicycle shops. The difficulty for the cyclist lies in choosing among good saddles, because only extensive experience that includes long rides will enable you to tell whether a saddle is right for you. There are two reasons for this. Obviously, a three-hour test won’t tell you if you are going to be bothered by pain that starts after six hours of riding. More important, as you use a saddle, your body becomes used to its particular shape and the saddle feels more comfortable, but simultaneously your body is losing its adaptation to saddles of different shape. Here is an example: from youth I rode on Brooks B17N leather saddles because these were the saddles that then were commonly supplied on good bicycles. In 1976, faced with the need to replace two saddles, I decided to try Cinelli plastic saddles on the two bicycles that I usually used in wet weather. After taking one of these on a two-week trip, on my return I found that riding my Brooks saddles had become painful. No matter how I tried, I could not keep my body accustomed to both Cinelli and Brooks saddles. Whichever I had been riding most recently was more comfortable than the one I had not been using.

This process of adaptation to the saddle that you ride may be the source of the folklore about saddle softness and the need to “break in” new saddles. The most common complaint about an uncomfortable saddle is that it is too hard. Therefore, many low-quality saddles, and some with higher pretensions, are covered with soft padding. It is also commonly believed that leather saddles are more comfortable than plastic saddles because they become soft with use and gradually conform to the rider’s body. Many cyclists have published recipes, some quite complicated, for softening new leather saddles, and one maker claims that its best model has been specially softened by an elaborate process. Folklore says that a new leather saddle is painful but that if you persevere it will become comfortable, and that a plastic saddle must be bought for initial comfort because it will not change shape with use. Because I was comfortable on my leather saddles when they were new, I never used any of the softening techniques. Rather, I protected my saddle from softening and stretching by protecting it from the rain whenever possible and never tightening the adjusting nut when the saddle was wet or had been recently used.

The match between your shape and the saddle’s shape is more important than anything else. I do not yet know enough about saddle fitting to tell you how to choose one. If you suffer from saddle pain or numbness, though, consider that the condition is more likely to be caused by the shape of the saddle than by its hardness, and it might even be caused by excessive softness. In particular, if you are a man, try a saddle that has a different width halfway back.

Adding soft padding is quite obviously wrong for women; it makes their problem far worse (see the following section). It is probably bad for men also. Padding merely distributes the cyclist’s weight over a larger area, without regard to whether that additional area is suitable for sitting on. For women, it certainly is not (as discussed in the following subsection). One of the problems for men is numbness of the penis after long rides. This is caused, according to one theory, by restriction of the flow of blood along the upper surface of the penis as it is lifted against the pubic bone. Obviously, added padding presses the penis more tightly against the pubic bone, and this presumably increases the problem.

The pain that develops during long rides is deep inside, around the points of the bones on which you ride. Softness in a saddle, whether plastic or leather, results in a hammock-like shape that concentrates its force at the points of greatest curvature—that is, precisely where the bones are pressing against it. It also spreads the force against areas that perhaps are less suited to sustaining it. A better distribution of force is obtained from a saddle that is sufficiently rigid to maintain its proper shape under load, thus protecting undesired areas from the force, while having flexible areas exactly where you should sit, so that the force is distributed over only these areas in a more equitable manner. The modern saddle with silicone-gel pads right where your bones press against it is a good example of thoughtful design.

Saddles for Women

A woman’s labia and clitoris extend downward, especially when she is “on the drops” in fast cycling posture. This becomes acutely painful in a short time. Thus, many women cannot ride in sporting posture on conventional saddles. Pelvic bones that are wide apart, as some women have, aggravate the problem because a woman with widely set bones sinks lower over her saddle, thus compressing her genitals harder against the saddle nose.

The answer is not to try to make a woman’s saddle softer by padding it; that exacerbates the problem by causing the saddle to press up against her over a larger area, including the area that hurts. The answer is to lower the portion she should not sit upon and to raise the portion she should sit upon. Tipping the saddle nose downward doesn’t work, because the rider than slides forward and puts too much weight on her arms.

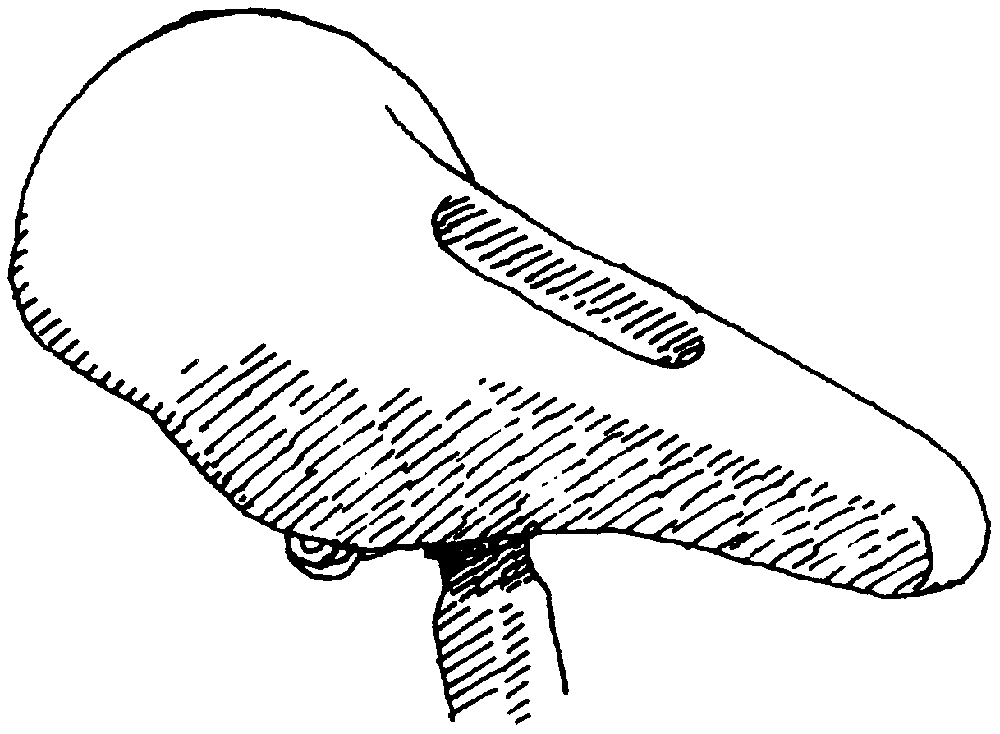

Uncovered plastic saddles can be modified rather easily. Start with something like the Unicanitor 50, a bare plastic shell (the model with only three holes in the top is the better one) that retails for about $10. Because it is about ⅜ inch wider in the waist than the Cinelli-Unicanitor saddles, it is likely to be a better fit for a woman. Ride on it long enough to see where it really hurts when you are otherwise comfortable on your bike. If your genitals are painfully pressed against the saddle, it will be on the centerline about a third of the way back from the saddle nose.

Cut a slot in the center of the saddle, as shown in figure 2.2. Typically, the slot should be 70 mm long, with its front end 90 mm back from the saddle nose. The slot should be about 12 mm wide at the front end and about 24 mm wide at the back end, with half-round ends and beveled edges. Carefully check the way you sit to adjust the slot if necessary. Saddle plastic is tough, but a rotary file in a high-speed, hand-held grinder cuts it very easily. If you do not have access to a high-speed grinder, drilling followed by lots of filing (rotary and otherwise) and scraping does an adequate job. While you are at it, file off the horizontal mold line and the brand name to keep them from wearing holes in your shorts.

Figure 2.2

A saddle modified for women. A bare plastic saddle is cut away at the place where it can become painful.

Then ride the saddle again to see how it feels. Enlarge the slot if necessary. However, if you feel that you are still too low on the saddle, or that it is still too high up inside your crotch, don’t enlarge the slot, but raise the two places that you should sit on. Locate the places where your pelvic bones should sit on the saddle, which should be two areas about 25 mm in diameter on each side of the saddle waist. Roughen them with emery cloth. Then apply a layer of silicone rubber sealant over these areas to make the saddle wider and higher there. Apply about 3–4 mm of silicone rubber. Smooth it down and feather the edges. Let it harden for at least 24 hours, after which it will be firm, tough, and rubbery. Then ride again to feel the improvement. Add another layer of silicone if it seems desirable.

You can cover the saddle with thin, soft upholstery leather. Lay the leather over the saddle and cut it with a margin of about ½ inch all around. Cut and sew one or two darts to fit the nose of the saddle. Coat the inside of the leather with contact cement, and immediately put it on the saddle. The cement will soften the leather, so by pulling the leather you will be able to achieve a wrinkle-free fit. Tuck the edges over the rim of the saddle, and trim off any excess. The soft leather will depress into the hole in the saddle, preventing the edges of the hole from wearing out your shorts.

Several women I know have commented that these treatments produce the most comfortable saddles they have ever ridden, and Dorris has discarded good leather saddles in order to ride on cheap plastic ones modified this way.