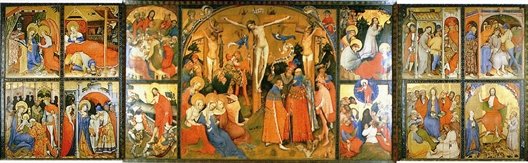

86. Conrad von Soest,

The Wildunger Altarpiece, c. 1403.

Oil on panel, 158 x 267 cm.

Bad Wildungen Church,

Bad Wildungen (Germany).

With this development, painting became more important and the artists were able to speak eloquently to the faithful. Painting’s natural language was quickly understood in the depiction of Mary alone, who to medieval man had become more worthy of devotion than Christ Himself. The half romantic, half crudely sensual cult of the feminine had so closely merged with the adoration of Mary, that the divine and the profane could no longer be separated. The painters of Cologne made it their indefatigable goal to depict an ideal Mary that also corresponded with their personal ideal of womanhood. They eventually had the satisfaction of seeing the lovely gracefulness of their paintings imitated by later masters, but hardly ever surpassed. These works brought the spiritual movement that had begun with minnesong, courtly epics, and religious didactic poetry to a close. The ‘spring’ of minnesong found its painterly equivalent not in the miniatures of the older manuscripts, but in the images of the Cologne school of painting. Each flower, each blade of grass was rendered true to life by the Cologne masters, who added these painstakingly gathered treasures as if they were threads of a woven carpet, which they spread beneath the feet of the blessed Mother of God.

Because of this poetic urge, painting developed earlier than drawing, and intensity of feeling came before expression of character. The Madonna herself vanished into an impersonal figure that usually represented the popular ideal of beauty; the depiction of her naked child, however, increasingly demonstrated a lack of anatomical knowledge. These shortcomings were more than compensated for with painterly appeal. For the first time the contrast of light and shadow appears, and paint becomes lighter or darker, depending on how much or how little it was exposed to light. From this game of opposites arose the accomplishment of modelling, which hitherto had been a prerogative of sculpture.

Cologne’s churches and museums hold most of the school’s major works, which are separated into an old and a new school. The old school began with Master Wilhelm: he created a small, winged altar that features, in its centre, the Madonna mit der Bohnenblüte (Madonna with Bean Flower), with St. Catharine on the left wing and St. Barbara on the right. A similar Madonna mit der Bohnenblüte can be found in the Germanische Museum (Germanic Museum) in Nuremberg; another Madonna mit dem Kind (Madonna with Child), who is surrounded by female saints on a flowering meadow, is in the collection of Museum of Berlin; there is also the Heilige Veronika (St. Veronica) with the face-cloth of Christ in the Alte Pinakothek museum in Munich. All these images are as characteristic of Cologne’s old school as they are of their environment.

The main exponent of the new school was Stephan Lochner who came from Meersburg at Lake Constance but moved to Cologne early in his career. Archival documents show that he worked frequently for Cologne council and seemed to have been wealthy. It is possible that he became one of the countless victims of the plague that ravaged Cologne in 1451. In 1435, he had painted Judgement Day, which features a multitude of figures. In 1440, he created his Dreikönigsaltar (Altar of the Three Kings), which was originally consecrated in 1462 for the chapel of the town hall, but which is now housed in Cologne Cathedral. The inside of the altar’s left panel shows St. Ursula with her retinue; the central panel features the Adoration of the Kings; and the inside of its right panel contains St. Gereon with his companions, the martyrs of the Theban legion. In 1810, it was moved to Agneskapelle (St. Agnes Chapel) in the cathedral. By the fifteenth and sixteenth century the painting had become so famous that Albrecht Dürer when he stayed in Cologne on his journey to the Netherlands in 1529 sacrificed two silver pennies to have Master Stephan’s panel opened. When the wings are closed, their exteriors show the Annunciation of Mary with the angel to the right and the blessed virgin to the left as she kneels on the prie-dieu of her chamber. Among Lochner’s later works are Geburt Christi (Birth of Christ, 1445), Darbringung im Tempel (Offering in the Temple, 1447) Madonna im Rosenhag (Madonna in the Rose Garden, c. 1440).

When Cologne’s bishop miraculously brought the relics of the Three Kings – the highest patron saints of the city – the noblest among the saints that were of particular importance to Cologne had been united. Master Stephan applied all his skills to the middle panel, which, in terms of glorious colours and subtlety in terms of painterly treatment, surpassed everything that painting of the time had to offer, including Italy. All details are executed with the same amount of love: the heads, which already show a variety of characterisation; the splendid clothes that were fashionable at the time; the weaponry; the precious gifts, which the Magi brought from the East; the carpet that angels hold behind the Madonna; as well as the flowers and plants that grow from the grass. These single impressions and the overall harmony of the piece – the poetic mood that irresistibly and powerfully communicates with the viewer – are all due to the use of colour. The golden background and the rich tracery of the row of arches that concludes the tops of the images are the only reminders of the role that architecture and sculpture had played in such altarpieces up until this point.

Cologne’s older school of painting reached its peak in the Kölner Dreikönigsaltar (Cologne Altar of the Three Kings). It was not destined to reach beyond the depiction of a beautiful, peaceful human existence thus make the transition to the dramatic or even the passionate. Wherever the altar tried to express the latter in images of the Passion or of martyrs, it slid into unrefined caricature, which was in unpleasant contrast to the lovely depictions of Heavenly peace. Painting’s further perfection and its complete absorption of nature were reserved for the Dutch School under the leadership of brothers, Jan and Hubert Van Eyck. Their work belongs to the following epochs.