Whispering to Donkeys (or Not!)

AFTER A YEAR of ineffectually yelling, “Reins the same length! Hands the same height!” Laura agreed to seek out specialized help with Caleb. She and I had struggled for months to transform my rambunctious donkey into the perfect riding animal. But his blithe indifference to commands baffled even the usually unflappable Laura. To be fair, she was a certified dressage riding instructor, not a horse trainer, per se. In the middle of desperately wrestling my thick-necked charger to stop or turn, frankly I couldn’t care less about the subtleties of the sport. If I would not, or could not, assume the role of alpha, as the Bridgmans and Laura demanded, I had to find another way to tame Caleb. And soon.

One day, Laura announced that her friend would introduce a new method of training to Silver Rock. As an avid reader, I already knew that a handful of horsemen and horsewomen had been teaching humane methods for thirty years. Sara, Laura said, had trained with one of them. Thinking more like Jane Goodall than General Patton, this new breed of trainer studied the subtle interplay of body language that wild horses use to establish dominance, show affection, and mete out discipline. They didn’t “break” a horse in the traditional way, by breaking its will or its spirit through intimidation and bullying. Instead, they sought ways to “gentle” the horse, as they called it.

I knew already that donkeys were not herd animals, but I still wasn’t clear how this social difference might affect training Caleb. The only donkey specialists I had interacted with, the Bridgmans, followed traditional horse-breaking methods.

The next time Sara came by the stable, I talked with her about our problems with Caleb. She took my concerns seriously. Laura must have discussed him already, because she said, “Oh yes. I heard.” Eager to see what a new trainer with a new method might achieve, I signed up for six weeks of Sunday sessions.

On the first morning of class, Caleb was already braying at full throttle at the sound of my car. I hugged the snuffling beast and groomed him. On our way to the dressage ring, he marched eagerly, head-butting me the whole way, as if I were the one who needed prodding. Inside the ring we joined eleven horses and their young owners. Caleb swung his head left and right, curious about his fellow pupils. He butted my arm and nibbled his new lead line. I nudged him and mumbled, “Keep still.” Once he had surveyed the setup, he rested his bony jaw on my shoulder. Hoping to keep him focused on me, I slipped him a cookie from my coat pocket.

Sara entered after me. The outfit she’d chosen matched a rather stiff demeanor: her long platinum-blond ponytail jutted out behind a precisely angled white cowboy hat; her tight pressed black jeans were tucked into shiny Western boots. Her first command was “Line up.”

I shoved Caleb’s chest back, then scurried around to the rear and leaned hard against his rump to shuffle him into rough alignment with the other horses. I, for one, was determined to put my best hoof forward.

Meanwhile, I strained to hear what the instructor said as she strutted back and forth along the line of attentive faces and muzzles. Wielding a long prod, Sara tapped the shoulder of one horse, the flank of another, to nudge them into a precise line. I had held the rod before class — while a nice carrot-orange color, its fiberglass shaft was as stiff as a golf club. To my mind, it masked a deadly weapon. The rod alone sparked my first misgivings about Sara’s supposedly humane philosophy.

She returned to the first horse in the row, a placid chestnut. She didn’t speak to the horse or touch him with anything other than her stick. As she proceeded down the line toward us, I whispered into Caleb’s furry ear, “She may act like a Nazi, but she’s just nervous.”

Sara appeared out of nowhere and planted her pointy boots inches from my sneakers. She said, “Stop talking to him. Verbal commands are a waste of time.”

I nodded meekly. Nevertheless, I talked to my donkey all the time. Books about donkeys and mules stated that the human partner’s voice was essential for longears — especially in new situations or when they couldn’t see you, such as when you’re riding them. If most of my words were meaningless blather, as Lou Bridgman had implied, then why did Caleb always twist his foot-long ears toward my voice?

Meanwhile, Caleb jammed his nose into my side pocket. Sara spun around and demanded, “Have you got treats in your pocket?”

I could hardly deny it. Donkey slobber had already darkened the bulging pocket.

“Treats are totally distracting to him and to the other horses here.”

“I’m sorry; you’re right.” I wondered where I could deposit the contraband without hauling the donkey off the field with me. As soon as Sara’s back was turned, I stuffed the remaining cookies into his mouth.

Our instructor mercifully ignored her least promising students for the rest of the hour, and we slunk off to the barn as soon as class was dismissed.

At our next class, as Sara marched down the row of students and horses, they appeared to be backing up a few steps.

“We can do this, Caleb,” I whispered.

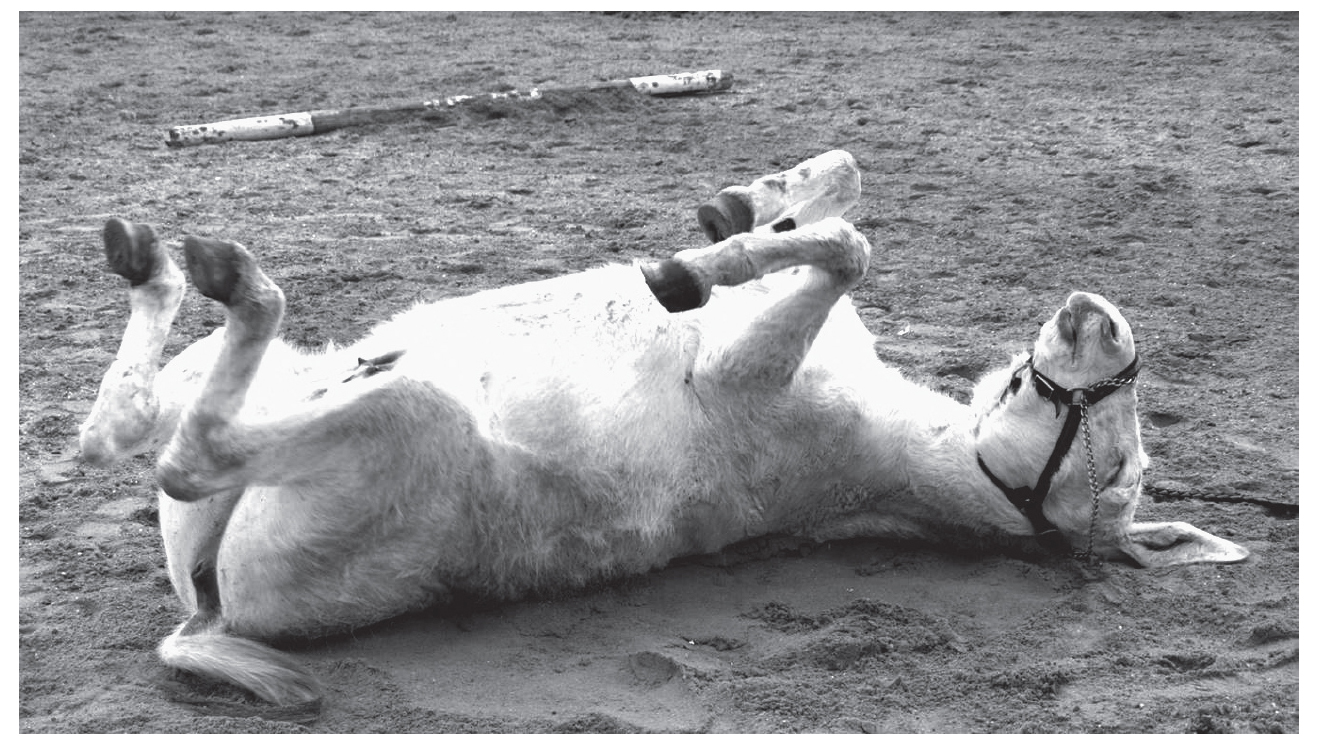

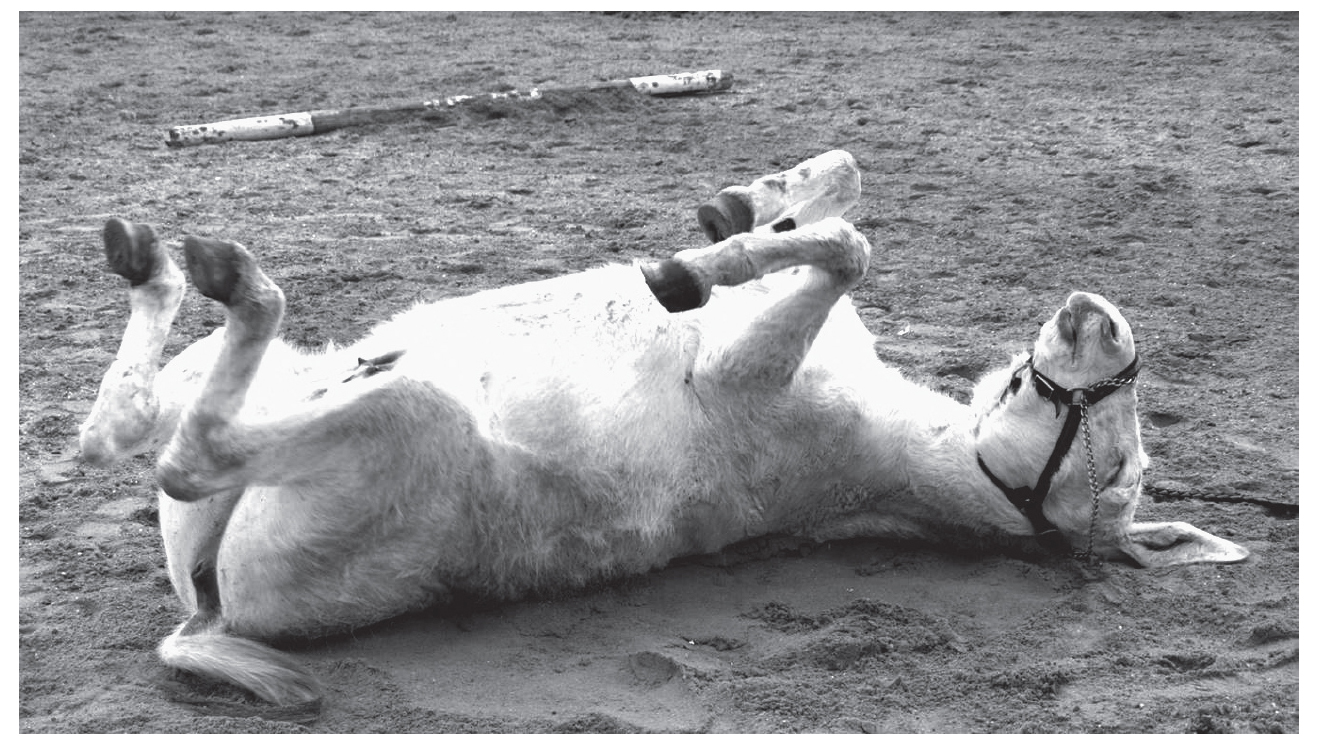

The next thing I heard was a loud thwump. In the gap where his big head and neck should have been, a cloud of dust engulfed me. I turned to find him rolling on the ground, groaning and grunting loudly like a cow in a difficult labor. All four of his legs bicycled the air as he writhed back and forth. He rubbed his ears and cheeks against the ground, his big whiskery nose and lips quivering in ecstasy.

Bliss! (photo by Bruce Mason)

“Get him up! Right now!” Sara was back.

This animal weighs seven hundred pounds, lady. You get him up.

As if reading my mind, Sara asked me in a quieter voice, “How do you get him up?”

I looked down at his flailing hooves and suppressed a smirk. “I don’t. He just gets up when he’s ready.”

Sara strode away, wisely choosing to ignore the troublemakers. She demonstrated some new technique to the next horse down the row.

Finished with his sand bath, Caleb stopped rolling and folded his legs under his belly and, with a loud grunt, heaved himself onto his feet. I stood facing front, in classic halter-class pose, bracing for the inevitable. A second later, he shook a pound of damp sand all over me. From his point of view, he was clean. I was filthy. Score one for Caleb.

Sara had been explaining something, which I had missed. She charged down the line to us, the dreaded Carrot Stick raised as if to strike us dead. She said, “Now you do it.”

“Do what?”

Sara sighed and gazed at the ground. With exaggerated slowness, she grasped Caleb’s lead line and jiggled it in front of his face.

She craned her neck toward an audience of fellow students and passersby and said, “Watch this. This will capture his attention. He’ll raise his head up and step back in line.”

She passed the line to me, and I jiggled the rope. It worked! He backed up. Score one for the Method. Once he understood the cue, he kept backing up. I joined the other students in jiggling their ropes, stepping their horses backward around and around the ring. This method was a great improvement over manhandling him. Caleb could back up forever. The class ended on a positive note. In his stall, we toasted our success with cookies.

The following Sunday, the donkey and I entered the ring ready to learn. When Sara joined the class, I pushed and shoved him back into line as fast as I could. (The jiggle method had stopped working the day after the last lesson.)

Caleb grabbed the rope and chewed on it. I didn’t mind, as gnawing on his rope acted as a potent pacifier. Unfortunately, no donkey transgression proved too small to escape Sara’s notice. The challenge Caleb and I presented apparently eclipsed the efforts of my classmates. She trotted up the line, zeroing in on us. She addressed the audience of kids and adults who sat in the grass outside the ring. “If you want your horse to stop chewing on the lead line,” she announced in a loud, clear voice, “you can use reverse psychology.” Echoes of Lou Bridgman.

Sara pointed at Caleb, whose eyes were half-closed as he munched blissfully. “He wants to put the rope in his mouth? Fine. Just feed him more line until he spits it out.”

Sara snatched the rope from me. Standing next to the donkey’s head, she crammed loops of wet, sand-encrusted rope into his mouth. Inch by inch, it disappeared into his willing maw. Caleb eagerly stretched his rubbery lips and arched his mouth wide to move the growing gob with his tongue to make more room for the next coil. From his pointed ears and bright eyes, I could almost read his mind. I can do this. Everyone is proud of me.

On the sidelines, people started to giggle. Sara accelerated her efforts, pushing larger coils into Caleb’s drooling mouth. He tossed his head and laid his ears back but hoovered up the next inch of line with deft maneuvers of his tongue. Was this supposed to be humane? I looked between the rope remaining in Sara’s hands and the short segment still lying on the ground. At least three feet of the sandy one-inch-diameter line — about the size of a cantaloupe — had disappeared, yet my donkey was still gamely tonguing another loop into his mouth. It dawned on me that he might choke or swallow sand and develop colic. How many people did it take to perform a Heimlich maneuver on a seven-hundred-pound donkey? And where, exactly, was his diaphragm?

Just as an objection bubbled up in my throat, Sara abruptly dropped the rope and turned on her heel. She stomped away, shaking her head and muttering, “He’s impossible.”

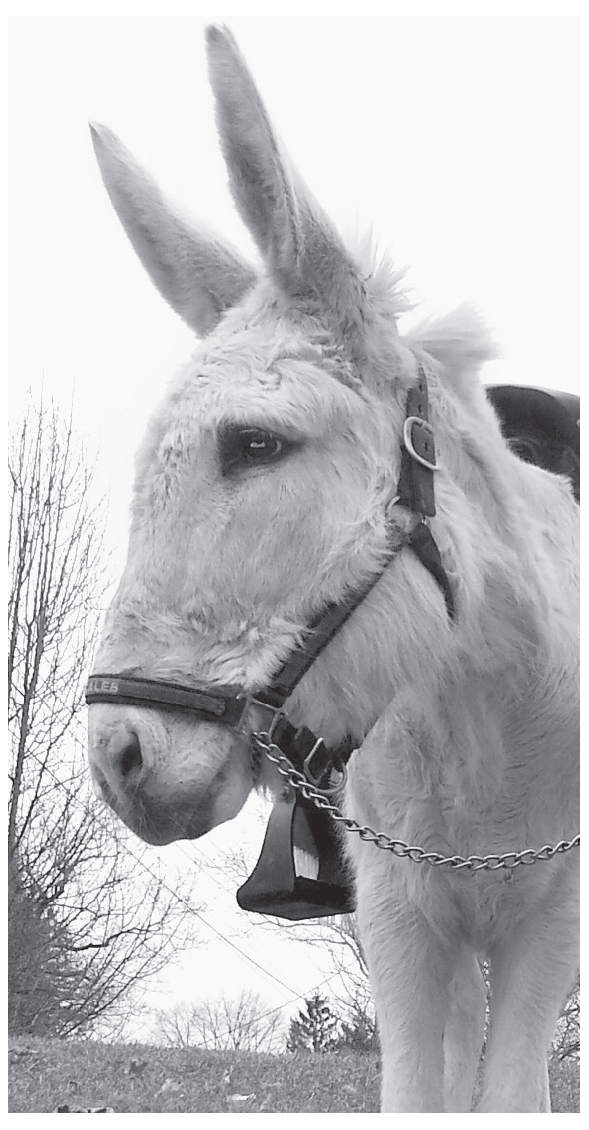

Caleb’s baleful expression during training (photo by Bruce Mason)

As soon as Sara’s back was turned, Caleb, with a guttural “GU-ROOSH,” spewed the steaming mess right between her shoulder blades.

This time no one hid their laughter. But Sara possessed sufficient pride not to wipe the slime-soaked sand off the back of her white shirt. Head held high, she reached the end of the row and set forth to teach the next training technique.

I picked up the sodden line, trembling from the belly up, trying not to laugh out loud. Score two for Caleb.

Between two weekend field trips with my students and extra meetings at the college, I hadn’t practiced as much as I had hoped. Nevertheless, I was determined to come away from the course with some techniques I could use. Maybe I would just chuck the sections that seemed unnecessarily aggressive, such as “friendly-ing the horse with the Carrot Stick.” Leaving aside the new vocabulary words, the pricey props, and so on, weren’t we still attempting to intimidate a large animal into submission? Then again, how else did an eighty-pound kid hope to control a half ton of equine muscle using a wimpy little piece of rope? At the same time, I couldn’t help but sympathize with my donkey’s rebellion against what was beginning to look, at least to me, like a sugarcoated form of bullying.

On the drive over to the stable for the next class, I considered our instructor’s point of view. No one liked to be humiliated in public. Before I had acquired Caleb, I was especially sensitive to people laughing at me unless I deliberately brought it on myself. With my donkey, however, I had inadvertently cast myself in the role of eternal straight man. I hoped that, like me, she could learn from Caleb to take life a little less seriously.

At the stable, I groomed a sleepy, innocent-looking donkey before leading him toward the dressage ring. I said, “Caleb, let’s not steal the show today, okay? Just do what she says for an hour. We can do that. Can’t we?”

We turned the barn’s corner and saw that the dressage ring was empty. Following the sound of excited voices, we merged with the other students leading their horses into the big ring, where a crowd of people were already jostling for room along the rails.

“Oh no.” I sighed. “It’s graduation day.” I had forgotten. Today was the last class, though Caleb and I had yet to master even the first lesson. I guided him out onto the field and trotted to the far end, hoping Sara would ignore us. And she should have, for her own sake as well as ours. But as soon as we were lined up, she headed straight for us.

“Here she comes,” I groaned under my breath.

Without preamble, Sara grasped Caleb’s lead line. Holding the Carrot Stick in her other hand, she waved it up and down next to his shoulder and jiggled the rope in his face. The maneuver worked. He stepped back. I looked on with a modest smile.

She didn’t stop there. With the line taut, she advanced on him, stomping her feet, and backed him into smaller and smaller circles. His ears dropped back to warning position, but he kept backing away from the orange whirlwind spinning near his face.

“Go, Caleb,” I whispered. Surely Sara was finished with the maneuver. Her least promising student had obeyed. So why did she continue to advance on him with the whirring stick and snapping rope? This must be one of the more advanced maneuvers taught on the days I missed. She pushed him into even tighter circles until he was tripping over his own legs. Cornered, he reared up, his rock-hard hooves punching the air over her head.

“Oh no!” I cried.

Caleb crashed down on all fours inches from Sara’s toes and bolted, dragging her over to the fence, where some small kids perched. I pursued my snorting donkey, calling, “Whoa. Easy, boy. Easy.”

The other students headed for the exit. Anyone could see that the donkey was confused and upset. Anyone, that is, except Sara. The donkey’s ears were pinned flat against his head, and he was breathing hard and fast. His coat streamed with sweat. Alone with Caleb and me in the ring, she planted herself directly in front of him and swung the stick in faster, bigger arcs.

“Wait. Wait,” I called out. I was paralyzed with indecision: Should I flee from the panicking donkey or stay in the ring? “Someone’s going to get hurt,” I told Sara.

She shouted at me, “Stay out of the way! You’re making things worse.” She advanced on him again, forcing him to back up. With the rope whipping back and forth like a crazed snake, he backed up several more steps, his eyes wide with fear. The moment I dreaded was close at hand.

In the space of a heartbeat, though, Caleb surrendered, but on his own terms. His knees buckled, and he sank to the ground. Rolling onto his side, he raised his head to look up at Sara with sad eyes. This time no one laughed.

Sara looked down at the sweaty, sand-caked mass and turned on me. “Get him up! Don’t let him do this to you.”

Do this to me?

We were all much safer with the upset animal on the ground, so I did nothing. But Sara wasn’t finished. She whipped his hind legs with the stick — not feeble taps with the tassel but full-armed wallops using the shaft. “Get up! Get up!” she yelled.

Caleb flinched with each blow, swung his head left and right, but stayed down. His ears lay limp and askew on each side, like broken wings. Rage jolted me out of my frozen terror. I rounded his flank and grabbed the stick from Sara.

“Stop it!” I screamed in her face. “Stop hitting him right now!”

Sara and I locked eyes. In those few seconds, I saw something I hadn’t noticed before: desperation. She dropped her gaze before I did, dropped the rope and stick on the ground, and strode toward the gate.

I looked down at my poor donkey. He stopped swaying his head from side to side and, with a loud sigh, laid his massive cranium in the dirt. There, in the middle of the ring under the watchful eyes of the onlookers, he closed his eyes.

I knelt by his head and said softly, “Come on, Caleb. Get up. Up. Let’s go. We’re finished here.”

He rolled onto his chest, struggled to his knees, and heaved himself up onto his feet. I picked up the rope and led him out of the ring, his ears still at half-mast, both of us avoiding eye contact with the silent audience. I couldn’t trust myself to speak.

Safely inside his stall, I touched the donkey’s sweaty flank and realized he, too, was trembling. I sang and whispered sweet nothings in his ears as I toweled him down. I almost wept with relief that he hadn’t turned on Sara or crashed the fence. In those few seconds of rising panic, this big, powerful animal could have trampled bystanders, including me. Or bolted off in a frenzy and broken his leg. I whispered to him, “But you didn’t hurt anyone, my good boy. Did you?”

As if in response, Caleb pawed the ground, first slowly, then faster and faster. I leaned over and picked up his hoof. Failing to achieve a high five, I shook his heavy foreleg up and down. “Way to go, Caleb!”