BY THE FOLLOWING FALL, Laura couldn’t help but notice that our floundering efforts at dressage traced a downward trajectory. Boredom tumbled after frustration in a race to the bottom. At one of our lessons, seemingly out of the blue, she announced, “I think Caleb and you need a new challenge.”

We hadn’t even mastered our first one. Not really, but I waited to hear about what new ordeal she had in mind.

“I want you and Caleb to prepare for the hunter pace at Pound Ridge.”

“A hunter pace? What is that?” Visions of red-coated riders galloping after hounds sprang to mind. Tallyho and all that.

“Look it up and we’ll talk,” she said.

I discovered that a hunter pace is a six- to ten-mile cross-country race through varying terrain, with intermittent jumps. Jumps?! Ahead of race day, members of the sponsoring riding club ride the course and record a slow time, a fast time, and an average. The times — like the length of the course — are kept secret until all entrants finish. (Or give up?) On race day, the rider who finishes the course closest to the average time, above or below, is the winner. So “the race is not to the swift.” I liked this biblical concept.

As the date for the hunter pace drew near, however, dread knotted my stomach. I approached Laura and asked, “Are you sure this hunter pace is a good idea?” Foremost on my mind was the memory of the horse that years ago had spooked in the woods and thrown me over his head.

She waved me off, but when I asked about the jumps, she set my mind at ease: “There are go-arounds at each jump, so you can skip them.” Laura added, “Mary Lee will be ‘ponying’ you on the pace. She’ll stay with you and guide you through the course.”

I didn’t know Mary Lee any better than any of the other “boarders,” as Laura called us. We were both professionals — she was a pediatrician — and about the same age. Mary Lee nodded when I said hello but, like all the serious riders, otherwise ignored me. I understood: Caleb and I blundered around the ring, cutting off riders and breaking equipment. I could almost read their minds: There goes the weirdo with the donkey.

In the plus column, I had often watched as Mary Lee rode Oscar, who was part draft horse, part Arabian. He was haughty, fierce, and huge. He looked like a medieval knight’s charger, heavy enough to carry a soldier in full armor, and more than ready to plow through a whole army of Saracens. If anyone would keep us moving, Mary Lee riding Oscar would ramrod us through.

On race day, as I groomed and saddled Caleb, I remembered the mayhem he had caused among Silver Rock’s horses and ponies when he first arrived. A few of them still bolted and threw their riders at the sight of him. “Forget about me, God,” I prayed. “Just don’t let us cause an accident.”

Soon Laura was urging us to load. I couldn’t resist asking her, “Isn’t showing up at a hunter pace with a donkey kind of like entering a yacht race with a rowboat?”

Laura reassured me with a pat on the shoulder. “You’ll be fine.”

Oscar’s stately form, all 1,700 pounds of him, clumped up the ramp of Mary Lee’s trailer. As we closed the ramp and doors behind Caleb, the donkey torqued his helicopter-blade ears toward Oscar, who calmly chomped on some hay. Caleb followed suit.

I climbed into the cab and aimed for an enthusiastic note: “Off to the races!” Mary Lee bit her lip and stared straight ahead. Apparently, she wasn’t pleased with her teammates. Six two-horse trailers from Silver Rock followed us up the highway and across the Tappan Zee Bridge. Forty minutes later, we entered a big field where dozens of other horse trailers were parked. All around us riders adjusted saddles and bridles and exercised their horses to stretch their legs.

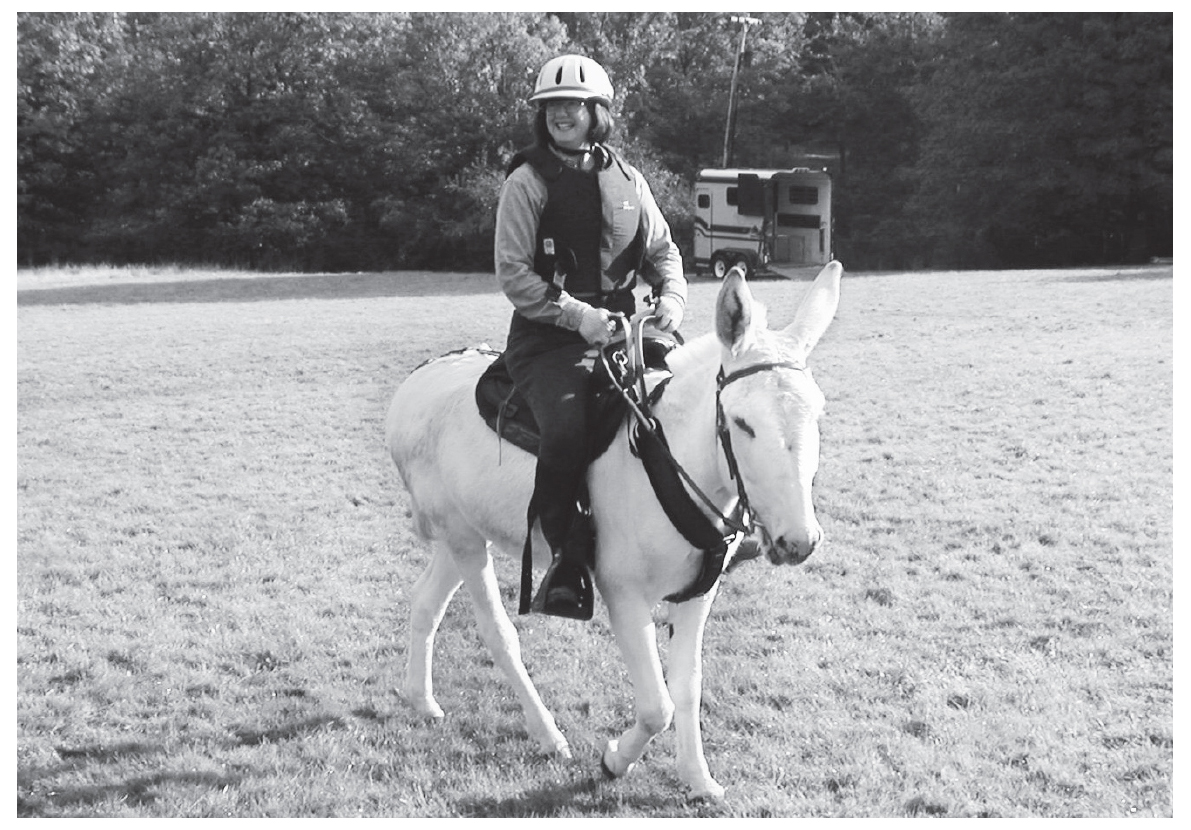

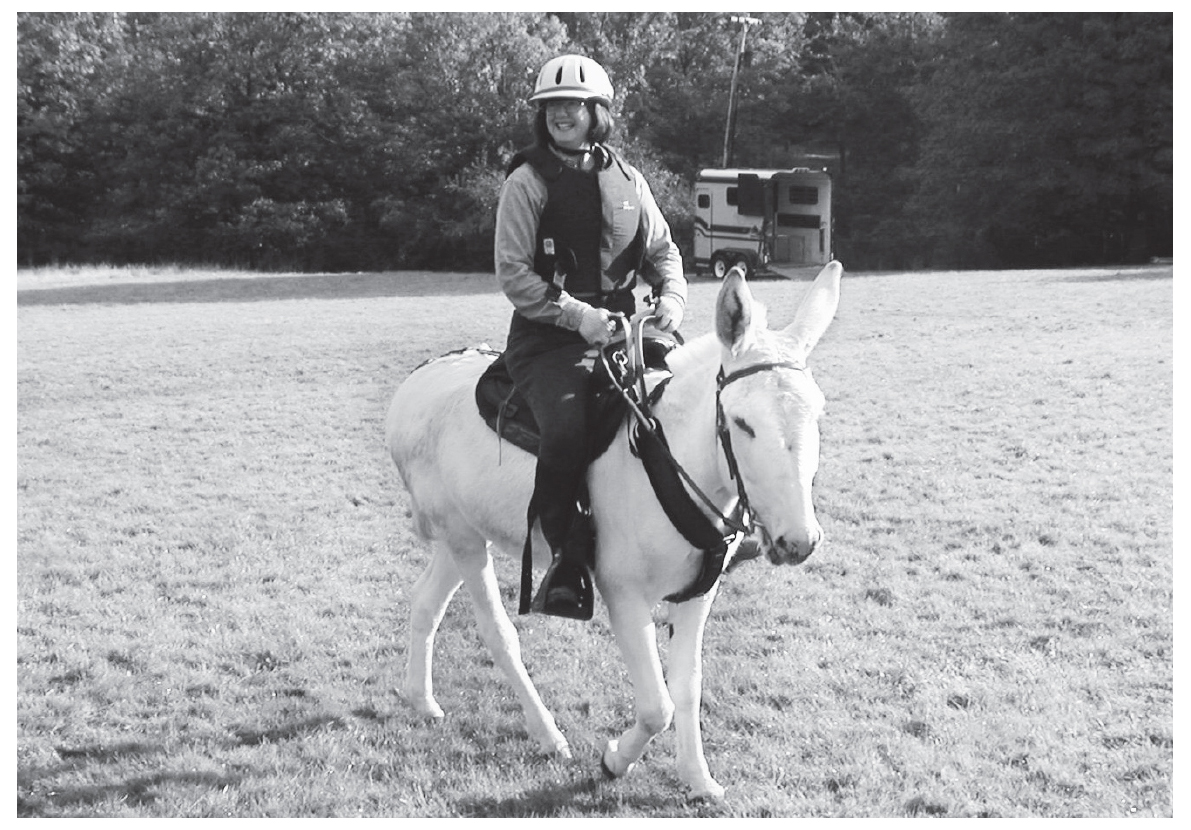

Hunter pace at Pound Ridge, New York (photo by Laura Butti)

A few minutes later, Laura brought over our numbered pinnies to slip over our clothes. “Number 56. Wow, now we look serious!” I looked around for another donkey, or even a mule. Among over one hundred huge Thoroughbreds, Arabians, and warmbloods, not a single pair of long ears pierced the sky. At last, I spotted two fat Icelandic ponies ridden by girls wearing jeans and hairy Icelandic sweaters. Maybe we could keep up with them.

To avoid traffic jams on the narrow trails, I learned, teams of two set out at three- to five-minute intervals. Laura had registered our team for an early start time so we would have plenty of time to finish. We followed Oscar toward the ill-defined start area, where several volunteer race officials held stopwatches and clipboards. In the crowd of eager horses, Caleb was barely able to contain himself. He circled and pawed the ground, bent on catching up to the horses that had started before us. I wasted precious energy circling him back into line.

Soon we received a nod from the official with a stopwatch and clipboard. Caleb raced into the woods ahead of Oscar, scrambling over the slippery rocks to catch up with the team ahead of us. In seconds, Oscar’s steaming nostrils nudged the donkey’s skinny butt, and Mary Lee passed me in a wide spot. She drawled over her shoulder in a faint Kentucky accent, “You’d better keep up.” And that was about all she said for the rest of the long day.

The donkey was forced to trot fast just to keep up with Oscar’s sedate stroll. “‘Keep up,’ she says!” I muttered at the donkey’s bouncing head. “Are you kidding?”

Oscar dashed ahead to the first jump and cleared it easily. Mary turned Oscar around and waited for us. Impatient with our slow pace, she lined Oscar up and vaulted the jump in the reverse direction, turned, and then jumped it again.

Caleb, inspired by Oscar’s triple performance, sped up. Except for that National Velvet moment when Caleb had fled the dumpster months earlier, we had never cleared more than a six-inch jump. This one, easily two feet high, was made of double rows of straw bales. “Oh no, Caleb!” With hard jerks and kicks, I steered him around it.

Rounding the next bend, Caleb picked his way carefully around sharp rocks and mud, following Oscar’s rapidly retreating rump. Every few minutes, Mary Lee reined Oscar in to wait. He snorted and pawed the ground, acting out his impatience on his rider’s behalf.

About a half hour into the race, a traffic jam ahead revealed a pileup of a dozen or so horses backing up and refusing to cross a wooden bridge. Instead of waiting his turn, Caleb plowed through the crowd. He stepped onto the slimy wooden deck and trotted across the bouncing bridge like a champ. Meanwhile, several horses panicked at the sight or maybe the smell of the donkey and bolted off the trail into the swampy woods, their enraged riders cursing as they struggled to rein them in.

“Oops! Sorry about that!” I waved as we hurried past. Now we were ahead of a dozen horses. “Way to go, honker-donk!”

As soon as we were safely past, muddy horses and their riders scrambled back onto the path. A minute later, they all galloped by, making a wide detour around us.

All morning, late-starting teams passed us. I soon retreated into “just-keep-moving mode” despite pains in my knee joints and butt from gripping my wide-backed mount like a nutcracker. Eventually I was too tired to be terrified of falling off a stumbling donkey. Whenever other teams passed us, Caleb trotted or cantered a few steps, as his equine pride demanded. But as soon as the other horses vanished around the next bend, he slowed to a pace not much more animated than his on-his-way-to-the-glue-factory shuffle.

On the downslope into a shallow valley I perked up at the sight of cars, tables, people, and horses milling about. “We’re done!” Caleb picked up on my renewed energy and trotted down to join the crowd.

Mary Lee burst my bubble. “It’s the halfway point. Vet check.”

Volunteers recorded the time of our arrival and scheduled a time-out. The vet in a white coat came over and placed her stethoscope against Caleb’s fuzzy breast. She smiled and said, “We heard that there was a donkey coming along.”

“I’ll bet you did,” I said. I could imagine the reports from enraged, muddy riders from the bridge crossing. After a quick rub of his neck, she said, “His heart rate is up, and he’s drenched in sweat. Better let him rest for ten minutes.”

Caleb and I were glad to comply, even though it forced Mary Lee and Oscar to linger, too. I didn’t dismount — I was afraid my stiff knees and aching hips wouldn’t cooperate if I attempted to remount. Volunteers offered slices of apple and water, which we four devoured. “Gee, we’ve done three or four miles in. . .what? An hour and a half?” I said to Mary Lee. She looked away.

“He thinks we’re done,” I said to a police officer who stroked the donkey’s velvety muzzle. The insignia on his uniform indicated that he was part of a mounted police unit. He smiled and said, “Never saw a donkey at one of these races.” I hoped that no complaints would reach his office.

When our ten minutes were up, I urged my steed into the woods behind Oscar. Caleb spun around and gazed longingly at the vet stop. “Hey! Treats back this way! You know: T-R-E-A-T-S!” he seemed to say.

Meanwhile, Mary Lee and Oscar started to attack the long slope of a major hill. I kicked, thrashed, and yelled until we were finally out of view of the vet station with its now-smirking volunteers. I figured that once he lost sight of the rest station, he would try to catch up with Oscar. But his hooves suddenly grew deep roots, and he even ignored the horses passing us. To his credit, we had already gone farther and faster than he and I had ever ridden before. There was nothing for it but to dismount. I limped up the hill in my stiff high-heeled riding boots, leading him by his reins. Caleb trotted along gamely at my shoulder, nipping my sleeve. “Aha! Better with the weight off, eh?” I puffed and grumbled as I towed him up the slope, not knowing — or even caring — if this disqualified us.

After a few minutes of steady trudging, I led him over to a tree stump and remounted. A few feet farther up the trail, though, he planted his feet again. No amount of yelling, whipping, or kicking made any difference. I dismounted. But this time he wouldn’t budge. I leaned back on the reins and applied the whip to his flank. Two women riders on their gleaming horses passed us. As late starters, they must have galloped to catch up, but their horses didn’t look at all winded. One rider called, “Is everything okay? Is one of you hurt?”

“No.” I sighed. “We’re just having a donkey moment.”

They laughed and pranced up the slope. Caleb suddenly decided to follow them. I could barely keep up. If I dropped the reins, he might finish the race without me. Or, just as likely, veer back downhill to the vet station and the treats.

When the horses disappeared around a bend, he stopped again. I had almost caught my breath when another team passed us. Caleb sped up again. When he lost sight of them, he stopped. With a tight grip on the reins, I bent over my knees to catch my breath. At least we’d made some progress.

“What is it? You don’t trust me when we’re all alone?” I wheezed into his ear. “Don’t think I know the way home?” He laid his ears straight back onto his massive head and squinted at me. “Well, you’re right. I haven’t a clue which way to go.”

Despite his ancestors’ semisolitary habits in the desert, this donkey had lived his life surrounded by humans, dogs, sheep, and goats, and more recently by as many as fifty horses and ponies. To him, following anyone anywhere trumped abandonment in the woods with his nitwit rider.

Long shadows descended the slope toward us. I looked up and scanned the ridgeline until I spotted the silhouette of Mary Lee and Oscar. They were waiting. To be sure, Oscar was spinning impatiently against the skyline. The sight of them restored hope. I led Caleb over to a boulder and mounted. I shouted, “Mary Lee, call to him!” Most horses don’t come to the sound of their names, but Caleb did, at least back at the stable. After a brief hesitation, Mary Lee called in a less-than-enthusiastic voice, “Come on, Caleb.”

“Louder!” I shouted.

“Cay-leb, Cay-leb. Come on, Caleb!”

At this, the tired donkey pricked up his ears and trotted up and over the rise to join his teammates. We followed Oscar along the sunny ridgeline.

On the downslope, I caught a glimpse of the parking lot. Oscar and Mary Lee must have seen it, too, as they galloped away to finish the race, perhaps to recoup some tiny piece of their dignity. Because the official time was based on the slowest rider in the team, Mary Lee had long since abandoned any hope of a ribbon, but she seemed eager to end her embarrassing ordeal, and maybe put some distance between herself and her hopeless teammates.

People from Silver Rock yelled Oscar’s name and cheered as Mary Lee galloped through the middle of the double row of sawhorses that marked the finish “chute” or “gate.” Two minutes later, my charger, who had picked up his pace in imitation of Oscar, slowed again to a saunter.

“Yay! Here comes Caleb!” At the sound of his name, his rabbit ears stood at attention. He sped up to a fast, bouncy trot again. But, instead of aiming for the finish line, he swerved off toward the cheering people in the parking lot.

“Oh no, you don’t!” I yelled. “We’re passing through the damned gate.”

I wrestled Caleb back in line with the chute. Disheartened, he dropped his head and slowed down to a hoof-stubbing shuffle.

“Thirty feet to go!”

The Silver Rock cheering squad urged us on. “Caleb! Caleb!”

I wished they hadn’t, because at the sound of all the voices, Caleb veered toward the outside of the sawhorses again. With the last of my strength, I turned him back. “We’re almost there! We are finishing, damn it!”

Halfway through the chute, he dropped his nose to the ground to graze on the short grass. I kicked and swung the whip, but he was done.

“It’s over.” My strength was long gone, and my will had screeched out of town an hour ago. But before I freed my cramped, sore feet from the stirrups, one of the judges heeded the clamor from Caleb’s fans and turned back from loading his truck. He strode toward us, no doubt to chew us out for keeping everyone waiting. I lowered my head and waited for his rebuke. Instead, he grabbed the bridle, and a surprised donkey followed the burly stranger through the chute to the finish line. Thunderous applause greeted us.

“We finished!” I said to my donkey’s sweaty ears as I tied him to the trailer. Caleb chomped on the grass as I rubbed him down. “You showed them: donkeys can do anything a horse can do.”

More or less.